Takeminakata

| Part of a series on |

| Shinto |

|---|

|

| Practices and beliefs |

| Shinto shrines |

| Notable Kami |

| Important literature |

|

| See also |

|

|

Takeminakata-no-Kami (建御名方神) or Takeminakata-no-Mikoto (建御名方命), also known as Minakatatomi-no-Kami (南方刀美神) or Takeminakatatomi-no-Mikoto (建御名方富命) is the name of one of the two principal deities of Suwa Grand Shrine in Nagano Prefecture (historical Shinano Province). Also known under the epithet Suwa Myōjin (諏訪明神) or Suwa Daimyōjin (諏訪大明神), he is considered to be a god of wind, water and agriculture, as well as a patron of hunting and warfare, in which capacity he enjoyed a particularly fervent cult from various samurai clans during the medieval period such as the Hōjō or the Takeda. The deity was also held to be the original ancestor of certain families who once served at the shrine as priests, foremost among them being the Suwa clan, the high priests of the Upper Shrine of Suwa who were also revered as the living incarnations of the god.

The Suwa deity is the subject of a number of different, often conflicting myths. For instance, in the Kojiki (720 CE) and later derivative accounts, Takeminakata appears as one of the sons of Ōkuninushi, god of Izumo and lord of Ashihara no Nakatsukuni (i.e. the land of Japan), who was forced into exile in the region of Suwa after being defeated by Takemikazuchi, an envoy sent by the gods of heaven, whereas other stories portray the god as being among other things a heavenly deity who conquered the Suwa region, an enlightened ruler of an Indian kingdom, a bodiless entity, or even a human warrior named Kōga Saburō.

Name

Etymology

The god is named 'Takeminakata' (建御名方神 Takeminakata-no-Kami) in both the Kojiki and the Sendai Kuji Hongi (aka Kujiki). Variants of the name found in the imperially commissioned national histories and other literary sources include 'Minakatatomi' (南方刀美神 Minakatomi-no-Kami or 御名方富命神 Minakatatomi-no-Mikoto-no-Kami) or 'Takeminakatatomi' (建御名方富命神 Takeminakatatomi-no-Mikoto-no-Kami).

The name's etymology is unclear. While most commentators seem to agree that take- (and probably -tomi) are honorifics, they differ in how to interpret the other components of the name. Some of the proposed solutions are as follows.

- The Edo period kokugaku scholar Motoori Norinaga[1][2] explained both take- (建) and mi- (御) as honorifics (称名 tatae-na), with kata (方) as yet another tatae-na meaning 'hard' or 'firm' (堅). Basil Chamberlain followed Motoori's lead and rendered the god's name as 'Brave-August-Name-Firm' in his translation of the Kojiki.[3]

- Historian Ōta Akira (1926) interpreted take-, mi- and -tomi as honorifics and took Nakata (名方) to be a place name: Nakata District (名方郡) in Awa Province (modern Ishii, Tokushima Prefecture), where Takeminatomi Shrine (多祁御奈刀弥神社) stands.[4] Owa Iwao (1990) explains the similarity between 'Takeminakata(tomi)' and 'Takeminatomi' by proposing that the name may have been brought to Suwa by immigrants from Nakata in Awa.[5]

- Minakata has also been linked to the Munakata (宗像) of Kyushu.[6] Imperial Navy colonel and amateur ethnographer Matsuoka Shizuo (1936) interpreted Minakatatomi as originally being a goddess – citing the fact that the deities of Munakata shrine were female – that was later conflated with the male god Takeminakata.[7]

- A number of more recent scholars have theorized that mina most likely means "water" (水), pointing to the god originally being a water deity and/or a connection to Lake Suwa.[8][9][10][11] The full name is thought to derive from a word denoting a body of water or a waterside region such as 水潟 (minakata, 'lagoon' or 'inlet')[6][10][11] or 水県 (mina 'water' + agata 'country(side)').[9]

- An alternative explanation for the word -tomi (as well as the -tome in 'Yasakatome', the name of this god's consort) is to link it with dialectal words for 'snake' (tomi, tobe, or tōbe), thereby seeing the name as hinting to the god being a kind of serpentine water deity (mizuchi).[12]

Suwa Daimyōjin

A common epithet for the god enshrined in Suwa Grand Shrine – specifically, in the Upper Shrine (Kamisha) located southeast of Lake Suwa – since the Middle Ages is Suwa Myōjin (諏訪明神) or Suwa Daimyōjin (諏訪大明神), a name also applied via metonymy to the shrine itself. A variant associated with the syncretic Ryōbu Shintō sect, Suwa (Nangū) Hosshō (Kamishimo) Daimyōjin (諏訪(南宮)法性(上下)大明神), "Dharma-Nature Daimyōjin of (the Upper and Lower) Suwa (Nangū[lower-alpha 1]),"[15] was most famously employed by Sengoku daimyō Takeda Shingen (a devotee of the god) on some of his war banners.[16][17]

Suwa Myōjin in mythology

While the deity of Suwa Shrine, officially named '(Take)minakata(tomi)' in the imperially-commissioned national histories of Japan, is already associated with the Takeminakata of the Kojiki (a son of Ōkuninushi and a deity of Izumo Province) in the Sendai Kuji Hongi (compiled 807-936 CE),[18][19] an identification repeated and popularized by the Suwa Daimyōjin Ekotoba (1356), other myths and legends, some from within Suwa itself, give completely different accounts of the god's origin and nature. In fact, most of the religious rituals of Suwa Shrine are actually not so much concerned with the official identities of its deities but with their character as Mishaguji, local agricultural and fertility deities.[20] The name 'Takeminakata' in fact does not appear in historical records of the Upper Shrine's ceremonies; rather, the focus of worship in many of these rituals are often identified in these texts as the Mishaguji.[21][22][23]

To reflect this distinction, this article shall use 'Takeminakata (of Izumo)' to refer to the figure described in the Kojiki, the Kuji Hongi, and other sources which use the name or some variant thereof, and 'Suwa Myōjin' or 'the Suwa deity' to refer to the god of Suwa Shrine as portrayed in other myths and in his capacity as shrine deity.

Origins

.png)

As Takeminakata of Izumo

Parentage

Takeminaka is portrayed in both the Kojiki and the Sendai Kuji Hongi as a son of earthly deity (kunitsukami) Ōkuninushi, ruler of Izumo Province. The Kojiki does not include him in its genealogy of Ōkuninushi's children,[24] although the corresponding section in the Kuji Hongi reckons him as the son of one of Ōkuninushi's wives, Nunakawahime of Koshi.[19][25]

Takeminakata and Takemikazuchi

Takeminakata appears in the Kojiki and the Kuji Hongi in the context of Ōkuninushi's "transfer of the land" (kuni-yuzuri) to the amatsukami, the gods of heaven (Takamagahara).[3][26]

When the gods of Takamagahara sent Takemikazuchi and another messenger[lower-alpha 2] to demand that Ōkuninushi relinquish his authority over the Central Land of Reed-Plains (Ashihara no Nakatsukuni) to the progeny of the sun goddess Amaterasu, he asked to confer with two sons of his first before giving his decision. While the first son, Kotoshironushi, immediately accepted their demands and advised his father to do likewise, the second, Takeminakata, carrying an enormous rock (千引之石 chibiki no ishi, i.e. a boulder so large it would take a thousand men to pull) on the fingertips of one hand, challenged Takemikazuchi to a test of strength, grabbing the messenger's arm.

Upon having his arm seized by Takeminakata, Takemikazuchi transformed it into an icicle and then a sword blade, preventing Takeminakata from holding onto it. In return, Takemikazuchi grasped Takeminakata's arm, crushing it like a reed and throwing it (or him) aside. The injured Takeminakata then fled in fear, pursued by the heavenly messenger. Upon arriving at "the sea of Suwa in the province of Shinano" (科野国州羽海), Takeminakata begged for his life, vowing not to leave Shinano at any pretext.

With Takeminakata's surrender, Ōkuninushi finally agreed to cede the land to the heavenly deities.[3][26][27][28][29]

Variants

The opening section of the Suwa Daimyōjin Ekotoba gives a summary of the Kuji Hongi version of this story, notably omitting any mention of Takeminakata's defeat under Takemikazuchi.[30]

Amaterasu-Ōmikami gave a decree and sent two gods, Futsunushi-no-Kami (of Katori Shrine in Sōshū) and Takeikatsuchi-no-Kami (of Kashima Shrine in Jōshū), down to the land of Izumo, where they declared to Ōanamuchi (of Kitsuki in Unshū [and] Miwa in Washū), "The Central Land of Reed-Plains is the land entrusted to our heir. Are you willing to give it up to the heavenly deities?"

Ōanamuchi said, "Ask my son, Kotoshironushi-no-Kami (of Nagata Shrine in Sesshū; eighth [patron deity of] the Jingi-kan); he will give you an answer."

Kotoshironushi-no-Kami said, "My father ought respectfully to withdraw, nor will I disobey."

[The messengers said,] "Do you have any other sons who ought to speak?"

"There is also my son, Takeminakata-no-Kami (of Suwa Shrine)."

[He] came, bearing a boulder that would take a thousand men to pull (chibiki no ishi) on his fingertips, saying, "Who is this that has come to our land, talking so furtively? I wish to challenge you to a test of strength."When he took his hand, it turned into an icicle, and then it turned into a sword blade [or 'he took a sword']. Upon arriving at the sea of Suwa in the land of Shinano, Takeminakata-no-Kami said, "I will go to no other place but this," etc. This is the origin story of this shrine's manifestation (当社垂迹の本縁 tōsha suijaku no hon'en).[lower-alpha 3][32]

A local legend in Shimoina District claims that Takemikazuchi caught up with the fleeing Takeminakata in the modern village of Toyooka, at which they both agreed to cease hostilities. The two then left imprints of their hands on a rock as a sign of their agreement. The rock, bearing the gods' supposed handprints (tegata), is found in Otegata Shrine (御手形神社) in Toyooka.[33][34] After Takemikazuchi's departure, Takeminakata temporarily resided in the neighboring village of Ōshika, hunting deer in the mountains, before making his way northward to Suwa. While there, he is reputed to have discovered the saltwater hot springs Ōshika is known for.[35][36][37][38]

In a few late retellings of the story, Takeminakata goes to Suwa not so much to flee from Takemikazuchi but to pacify it under the orders of his father Ōkuninushi.[39]

The contest between Takemikazuchi and Takeminakata has also sometimes been interpreted as an origin myth for sumo wrestling.[40][41]

Alternative locations

Whereas the place where Takeminakata was caught, "the sea of Suwa," is commonly understood as referring to Lake Suwa in Nagano, there have been a number of attempts in the past to identify this "Suwa" with other areas, such as the provinces of Suō (based on its proximity to Izumo and the claimed similarity between the two toponyms) or Hizen (cf. Suwa Shrine in Nagasaki).[42]

The Ōhōri and the bodiless Suwa deity

Before the abolition of the Suwa Grand Shrine's traditional priestly offices during the Meiji period, the Upper Shrine of Suwa's high priest or Ōhōri (大祝 'great priest'; also Ōhafuri) was a young boy chosen from the Suwa clan, who was, during his term of office, considered to be a living god, the visible incarnation or 'body' of the unseen Suwa deity.[43][44]

The legend of how Suwa Myōjin chose his first priest is recounted in various sources, such as the Suwa Daimyōjin Ekotoba:

At the beginning of the god's manifestation, he took off his robe, put them on an eight-year-old boy, and dubbed him 'great priest' (Ōhōri). The god declared, "I do not have a body and so make this priest (hōri) my body."

This [boy] is Arikazu (有員), the priest of the sacred robe (御衣祝 Misogihōri), the founding ancestor of the Miwa/Jin (神, i.e. Suwa) clan.[lower-alpha 4]

Although most sources (such as the Ekotoba above) identify the boy with the semi-legendary priest Arikazu, who is said to have lived during the reign of Emperor Kanmu (781-806) or his immediate successors Heizei (806-809) or Saga (809-823),[46][47][48][49] two recently discovered genealogical lists - of disputed historical reliability[50][51][52][53][54][55] - instead identify the first priest with Otoei (乙頴) or Kumako (神子 or 熊古), a son of Mase-gimi (麻背君) or Iotari (五百足), head of the Kanesashi (金刺, also 'Kanasashi') clan and kuni no miyatsuko of Shinano Province during the late 6th century.[56][57][58]

One of these two texts is a genealogy of the Aso (阿蘇) clan of Aso Shrine in Kyushu known as the 異本阿蘇氏系図 (Ihon Asoshi Keizu).[59][60] It reads in part:

Otoei (Ōhōri of the great god of Suwa): also known as Kumako (神子) or Kumako (熊古).

When he was eight years old, the great god Minakatatomi-no-Mikoto appeared, took off his robe and put them on Kumako, declaring, "I do not have a body and so make you my body." In the third month of the second year of Iware Ikebe no Ōmiya (587), a sanctuary (社壇) was built at the foot of the mountain at the southern side of the lake (i.e. Lake Suwa) to worship the great god of Suwa and various other gods ...[lower-alpha 5]

The other is the Ōhōri-ke Jinshi Keizu (大祝家神氏系図), a genealogy of the Suwa clan discovered in the Ōhōri's residence in 1884 (Meiji 17).[61][62][63] It portrays Arikazu as a descendant of Kumako, the priest chosen by the deity (identified here as Takeminakata of Izumo):

When Kumako was eight years old, the revered deity appeared, took off his robe and put them on Kumako. After declaring, "I do not have a body and so make you my body," he disappeared.[lower-alpha 6] This [Kumako] is the ancestor of Arikazu of the Miwa/Jin (Suwa) clan, the Misogihōri. In the second year of Emperor Yōmei, Kumako built a sanctuary at the foot of the mountain at the southern side of the lake. [lower-alpha 7]

As a god from heaven

Whereas the Kojiki portrays Takeminakata as an earthly god defeated by a deity from heaven, a myth from Suwa itself features the exact opposite scenario, in which Takeminakata / Suwa Myōjin is the heavenly deity who descends and conquers the land below.

A petition (解状 gejō) submitted to the Kamakura shogunate in 1249 by Suwa Nobushige, then high priest of the Upper Shrine,[64][65][66] recounts an origin myth of the Upper Shrine wherein the Suwa deity - here unnamed - is portrayed as coming down from the heavens to wrest control of the land of Suwa from 'Moriya Daijin'. [67][68][69][70]

As an Indian king

A medieval Buddhist legend portrays Suwa Myōjin as a king from India who later achieved enlightenment and went to Japan to become a native kami.

A short text attached to an ordinance regulating the Upper Shrine's ritual purity taboos (物忌み monoimi) originally enforced in 1238 and revised in 1317, the Suwa Kamisha monoimi no rei no koto (諏訪上社物忌令之事),[71] relates that the Suwa deity, 'Takeminakata Myōjin' (武御名方明神), was originally the ruler of a certain Indian kingdom called 'Hadai' (波堤国 Hadai-koku)[lower-alpha 8] who survived an insurrection instigated by the rebel Moriya (守屋 or 守洩) during the king's absence while the latter was out hunting deer. After going to Persia to rescue its inhabitants from an evil dragon, the king ruled over it for some time as 'Emperor Suwa' (陬波皇帝 Suwa Kōtei) before retiring to "cultivate the seedling of virtue and realize the Buddhist path." He eventually manifested in Japan, appearing in various places before finally choosing to dwell in Suwa.[74][75][76][lower-alpha 9]

The Suwa Daimyōjin Ekotoba relates a slightly different, fuller version of the first half of this story as an origin myth for the Upper Shrine's hunting ceremony held every seventh month of the year at Misayama (御射山) on the slopes of the Yatsugatake Mountains:

If one should inquire about the origins (因縁 in'en, lit. 'causes and conditions') of this hunt: long ago, the Daimyōjin was the king of the land of Hadai in India who went out to hunt at Deer Park from the twenty-seventh to the thirtieth day of the seventh month. At that time, a traitorous vassal named Bikyō (美教) suddenly organized an army and sought to kill the king. The king, ringing a golden bell, looked up to heaven and shouted eight times: "I am now about to be killed by this rebel. I have hunted animals, not for my own enjoyment, but in order to lead them to the Buddhist path. If this my action is in accordance with Heaven's will, may Brahmā save me."

Brahmā then saw this and commanded the four great deva-kings to wield vajra-poles and destroy the army. It is said that the Misayama (三齋山) of today reflects that event.

... One should know, therefore, that the deity's compassionate hunting is an expedient means for the salvation of creatures.[77][lower-alpha 10]

Regarding the Upper Shrine's hunting rituals, the Monoimi no rei asserts that

[The shrine's] hunts began in the deer park of Hadai-no-kuni [in India]. [The use of] hawks began in Magada-no-kuni.[79]

The second half of the legend (the slaying of the dragon in Persia and the king's migration to Japan) is used by the Ekotoba's compiler, Suwa Enchū, in a liturgical text, the Suwa Daimyōjin Kōshiki (諏方大明神講式),[80][81][74] where it is introduced as an alternative, if somewhat less credible, account of the Suwa deity's origins (in comparison to the myth of Takeminakata of Izumo as found in the Kuji Hongi, touted by the same text as the authoritative origin story of the god) that nevertheless should not be suppressed.[82]

Ancestry

The Suwa Daimyōjin Kōshiki claims the king of Hadai to be a great-great-grandson of King Siṃhahanu (獅子頬王 Shishikyō-ō), Gautama Buddha's grandfather.[83]

A similar account appears in a work known as the Suwa Jinja Engi (諏訪神社縁起) or Suwa Shintō Engi (諏訪神道縁起),[84] wherein the Suwa deity is identified as the son of Kibonnō (貴飯王), the son of Amṛtodana (甘呂飯王 Kanrobonnō), one of Siṃhahanu's four sons. The Lower Shrine's goddess, meanwhile, is the daughter of Prasenajit (波斯匿王 Hashinoku-ō), claimed here to be the son of Dronodana (黒飯王 Kokubonnō), another son of Siṃhananu.[85]

The Suwa Mishirushibumi

During the Misayama festival as performed during the medieval period, the Ōhōri recited a ritual declaration supposedly composed by the Suwa deity himself known as the Suwa Mishirushibumi (陬波御記文),[86] which begins:

I, Great King Suwa (陬波大王), have hidden my person during [the year/month/day of] the Yang Wood Horse (甲午 kinoe-uma).

[The name] 'Suwa' (陬波) and [the sign] Yang Wood Horse [and] the seal (印文)[lower-alpha 11] - these three are all one and the same.[lower-alpha 12]

Within the text, King Suwa (i.e. Suwa Myōjin) declares the Ōhōri to be his 'true body' (真神体 shin no shintai) and the Misayama (三斎山) hunting grounds below Yatsugatake (here likened to Vulture Peak in India) to be another manifestation of himself that cleanses (斎) the three (三) evils: evil thoughts, evil speech and evil actions.[90][91] He promises that whoever sets foot at Misayama will not fall into the lower, evil realms of existence (悪趣 akushu); conversely, the god condemns and disowns whoever defiles this place by cutting down its trees or digging out the soil.[92]

A commentary on the Mishirushibumi, the Suwa Shichū (陬波私注 "Personal Notes on the Suwa Mishirusibumi," written 1313-1314),[93] elaborates on the text by retelling the legend of Suwa Myōjin's consecration of his first priest:

The Daimyōjin was born during [the year/month/day of] the Yang Wood Horse and disappeared during [the year/month/day of] the Yang Wood Horse.

Sokutan Daijin (続旦大臣) was the Daimyōjin's uncle who accompanied him from India. When the Daimyōjin was to disappear, he took off his garments, put them on the Daijin, and dubbed him the Misogihōri (御衣木法理). He then pronounced a vow: "You shall consider this priest to be my body."[lower-alpha 13]

The same text identifies the god's uncle Sokutan Daijin with Arikazu.[95][96][lower-alpha 14]

As Kōga Saburō

A popular story promulgated by wandering preachers associated with the shrines of Suwa during the medieval period claimed the Suwa deity to have originally been a man who temporarily became a dragon or a snake after a journey into the underworld.[98][99][100][101] Many variants on the basic story exist; the following summary is based on the earliest literary version of the tale found in the Shintōshū.[102][103]

The third son of a local landlord of Kōka District in Ōmi Province, a distinguished warrior named Kōga Saburō Yorikata (甲賀三郎諏方) was searching for his lost wife, Princess Kasuga (春日姫 Kasuga-hime) in a cave in Mount Tateshina in Shinano, with his two elder brothers. The second brother, who was jealous of Saburō's prowess and fame and who coveted Kasuga, traps the latter inside the cave after they had rescued the princess.

With no way out, Saburō has no other choice but to go deeper into the cave, which was actually an entrance to various underground realms filled with many wonders. After travelling through these subterranean lands for a long period of time, he finally finds his way back to the surface, only to find himself transformed into a giant snake or dragon. With the help of Buddhist monks (who turn out to be gods in disguise), Saburō regains his human form and is finally reunited with his wife. Saburō eventually becomes Suwa Myōjin, the god of the Upper Shrine of Suwa, while his wife becomes the goddess of the Lower Shrine.[102]

This version of the legend explains the origin of the name 'Suwa' (諏訪 or 諏方) via folk etymology as being derived from Saburō's personal name, Yorikata (諏方).[104]

It has been proposed that the Kōga Saburō legend arose as a result of the collapse of the Kamakura shogunate and the downfall of the Hōjō clan, which the Suwa clan had faithfully served as retainers. The status and prestige of the Ōhōri having been diminished in the aftermath of these events, localized stories about Suwa Myōjin such as that of Kōga Saburō began to circulate among devotees of the Suwa cult.[105]

Arrival in Suwa

Both the official records of the central Yamato government and local myths agree in portraying the god of Suwa as an outsider who migrated into the region.[106] Stories of how Suwa Myōjin arrived in Suwa and established himself therein are related below.

Entering Shinano

One folk story relates that Takeminakata, upon being driven away from Izumo, first went to visit his mother Nunakawahime in Koshi before proceeding southwards into Shinano. Upon reaching Azumi (modern Kitaazumi District) on the northernmost part of the province, the local deity would not let him through the pass of Sanosaka (modern Hakuba Village). Takeminakata temporarily retreated to Mount Minekata (also in Hakuba), where messengers sent by the gods Ikushima-no-Kami (生島神) and Tarushima-no-Kami (足島神) arranged safe passage for him into the province.[107]

En route to Suwa, Takeminakata visited the gods Ikushima and Tarushima in what is now the city of Ueda and offered them gruel.[108]

Before entering Suwa, Takeminakata stayed for some time in what is now Ono Shrine in Shiojiri, as he tried to find a way to defeat the god Moreya.[109][110] Ono Shrine's Nenjiribō Matsuri held in January 6th, a contest in which locals scramble for long wooden poles,[111] is claimed in legend to have been originally devised by Takeminakata and his retinue as a way to boost their morale during their stay.[112][113]

Moreya

.png)

One god that opposed Suwa Myōjin upon his arrival in Suwa according to local myths was the god Moreya (Moriya).

Suwa Nobushige's 1249 petition relates a story from "the ancient customs" (舊貫) that the Suwa deity came down from heaven in order to take possession of the land of Moriya Daijin (守屋大臣). The conflict between the two escalated into a battle, but as no winner could be declared, the two finally compete in a tug of war using hooks (kagi): Suwa Myōjin, using a hook made out of the wisteria plant (藤鎰), emerges victorious against Moriya, who used an iron hook (鐵鎰). After his victory, the god built his dwelling (what would become the Upper Shrine) in Moriya's land and planted the wisteria hook, which became a grove known as the 'Forest of Fujisuwa' (藤諏訪之森 Fujisuwa no mori).[lower-alpha 15][68][64][69][70][66]

The Suwa Daimyōjin Ekotoba relates a variant of this myth as an origin story of Fujishima Shrine in Suwa City, one of the Upper Shrine's auxiliary shrines where its yearly rice-planting ceremony is traditionally held.[114][115][116][117] In this version, the Suwa deity defeats "Moreya the evil outlaw" with a wisteria branch:

As for this so-called Fujishima no Myōjin (藤島明神): long ago, when the revered deity (尊神 sonshin) manifested himself, Moreya the evil outlaw (洩矢の惡賊) sought to hinder the god's stay and fought him with an iron ring (鐵輪), but the Myōjin, taking up a wisteria branch (藤の枝), defeated him, thus finally subduing heresy (邪輪 jarin, lit. "wheel/circle/ring of evil") and establishing the true Dharma. When the Myōjin swore an oath and threw the wisteria branch away, immediately it took root [in the ground], its branches and leaves flourishing in abundance, and [sprouted] beautiful blossoms, leaving behind a marker of the battleground for posterity. 'Fujishima no Myōjin' is named thus for this reason.[lower-alpha 16][118][119]

.jpg)

The Suwa Daimyojin Kōshiki integrates this story into the legend of the king of Hadai by portraying Moreya as an incarnation of Bikyō, the rebel who raised up an army against the king in India (cf. the version in the Monoimi no rei, wherein the king is opposed by a rebel named 'Moriya').[120]

In later versions of this story which combine it with the kuni-yuzuri myth, Moreya opposes Takeminakata after the latter had fled from Izumo. After being defeated, Moreya swears fealty to Takeminakata and becomes a faithful ally.[121][122] Moreya is reckoned as the divine ancestor of the Moriya (守矢) clan, one of the former priestly lineages of the Upper Shrine.[123]

While earlier sources such as Nobushige's petition and the Ekotoba situate the battle between the two gods somewhere in the vicinity of the Upper Shrine (modern Suwa City),[124] modern retellings instead place it on the banks of the Tenryū River (modern Okaya City).[121][122][123][125]

.jpg)

Yatsukao (Ganigawara)

Another god that is said to have opposed Suwa Myōjin and his new ally Moreya in local folklore was Yatsukao-no-Mikoto (矢塚男命), also known as Ganigawara (蟹河原長者 Ganigawara-chōja).[126][127][128]

After Moreya's defeat, Ganigawara held Moreya in contempt for surrendering to Takeminakata and had messengers publicly harass him by calling him a coward. When Ganigawara's servants began to resort to violence, Takeminakata retaliated by invading Ganigawara's turf. Mortally wounded by an arrow in the ensuing battle, Ganigawara begs forgiveness from Moreya and entrusts his youngest daughter to Takeminakata, who gives her in marriage to the god Taokihooi-no-Mikoto (手置帆負命) a.k.a. Hikosachi-no-Kami (彦狭知神)[lower-alpha 17], who was injured by Ganigawara's messengers as he was keeping watch over Takeminakata's abode.[132][133]

Other deities

A few scattered local legends make reference to other deities who either submitted to the Suwa deity or refused to do so.

In one legend, a god named Takei-Ōtomonushi (武居大伴主 or 武居大友主) swore allegiance to Suwa Myōjin and became the ancestor of a line of priests in the Lower Shrine known as the Takeihōri (武居祝).[134][126] Another story relates that the Suwa deity forbade the goddess of Sakinomiya Shrine in Owa, Suwa City from building a bridge over the creek before her shrine as punishment for her refusal to submit to him.[126][135]

Subduing the toad god

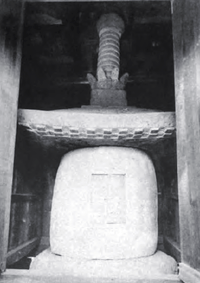

Two texts, the Monoimi no rei[136][137] and the Suwa Shichū (陬波私注 "Personal Notes on the Suwa Mishirusibumi," written 1313-1314),[93] mention an oral legend about Suwa Myōjin pacifying the waves of the four seas by subduing an unruly and savage toad god (蝦蟆神).[lower-alpha 18][lower-alpha 19] After defeating the toad, Suwa Myōjin then blocked the way to its dwelling - a hole leading to the underwater palace of the dragon god of the sea, the Ryūgū-jō - with a rock and sat on it (御座石 Goza-ishi or 石(之)御座 ishi no goza "stone seat").[lower-alpha 20][lower-alpha 21][93][139][140][141]

This story functions as an etiological legend for the annual sacrifice of frogs held every New Year's Day in the Suwa Kamisha (see below)[142] as well as yet another folk etymology for the toponym 'Suwa', here explained as deriving from a term for a wave lapping onto the sea's edge (陬波 namishizuka).[143]

The portrayal of Suwa Myōjin's enemy as a toad or a frog also hints at Suwa Myōjin's character as a serpentine water god, frogs being preyed upon by snakes.[143] (As a point of comparison, the obscure snake god Ugajin was also credited with defeating a malevolent frog deity.[144]) The toad god itself has been interpreted either as representing the native deities Mishaguji and/or Moreya, with its defeat symbolizing the victory of the cult of Suwa Myōjin over the indigenous belief system,[145][146] or as a symbol of the Buddhist concept of the three poisons (ignorance, greed, and hatred), which Suwa Myōjin, as an incarnation of the bodhisattva Samantabhadra, his esoteric aspect Vajrasattva and the Wisdom King Trailokyavijaya (interpreted as a form of Vajrasattva), is said to destroy.[144]

The current whereabouts of the Goza-ishi is unclear. The Monoimi no rei claims it to have been located "within the Shōmen" (正面之内ニ在リ, i.e. the 'upper plateau' (上壇 jōdan) of the Kamisha Honmiya where the inner sanctum is) and reckons it as one of seven sacred stones or rocks (七石 nana-ishi) associated with the shrine.[147][148] While three of the seven stones are indeed located within the Kamisha Honmiya - the Suzuri-ishi (硯石),[149] the (O)kutsu-ishi (御沓石),[150] and the Kaeru-ishi (蛙石)[151] or Kabuto-ishi (甲石) - none of these are currently referred to as Goza-ishi.[152][153] Nevertheless, attempts have been made to identify the Goza-ishi with any one of these three rocks.[154]

Hara (2012) proposes the Goza-ishi to have been the same rock as the Kaeru-ishi / Kabuto-ishi (the precise location of which is itself under dispute), noting that two sources from the Edo period both claim the Kaeru-ishi to be beneath a stone pagoda once located in the inner sanctum known as the Tettō (鉄塔 "iron tower"; see below), considered before the separation of Buddhism and Shinto in the Meiji period to be the physical 'body' (go-shintai) of the god of Suwa and the Kamisha's main object of worship,[155][156] and that the 18th-century traveller and ethnologist Sugae Masumi (菅江真澄, 1754-1829[157]) reported that the frogs sacrificed during the New Year's Day ritual were offered up to an iwakura (磐座, a 'rock-throne' or sacred rock) in the shrine.[156][151]

Meanwhile, a map of the Kamisha dating to the Tenshō period (1573-1592) depicts a rock labelled Goza-ishi located beside the Tenryūsui-sha (天流水舎), a building with a hole or pipe in its roof meant to collect the three drops of water said to miraculously trickle into it everyday no matter the weather.[158][159] One author has interpreted this to mean that the Goza-ishi was moved outside the inner sanctum once Buddhism became more firmly entrenched in the shrine and iwakura worship became less important.[160] However, no such rock currently exists beside the edifice.

Outside of the Kamisha, Goza-ishi Shrine[161] (御座石神社, also Gozansho[162]) in the city of Chino, Nagano houses a stone which is sometimes identified with the elusive Goza-ishi.[163][140] Kanai (1982) meanwhile believed the Goza-ishi to originally refer to a large boulder in the artificial Lake Shirakaba[164] (白樺湖), a former wetland at the foot of Mount Tateshina, underneath which a cavern containing ancient pottery and stoneware[165] - interpreted by Kanai to be ritual goods and a sign that the area once had religious significance[163] - was discovered when a levee breach drained the lake in 1954.[163][140][166]

Travel to Izumo

According to a local folktale, Suwa Myōjin is one of the very few kami in Japan who do not leave their shrines during the month of Kannazuki, when most gods are thought to gather at Izumo Province and thus are absent from most of the country.

The folktale relates that Suwa Myōjin once came to Izumo in the form of a dragon so gigantic that only his head can be seen; his tail was still at Suwa, caught in a tall pine tree by the shores of the lake. The other gods, upon seeing him, were so astounded and frightened at his enormous size that they exempted him from attending their yearly meetings.[167][168] The supposed tree where the dragon's tail was caught (currently reduced to a stump) is locally known as Okakematsu (尾掛松).[169]

A variant of this story transposes the setting from Izumo to the Imperial Palace in Kyoto; in this version, the various kami are said to travel to the ancient capital every New Year's Day to greet the emperor.[170]

Omiwatari

Cracks and ridges that form on a frozen Lake Suwa during cold winters have traditionally been interpreted as the trail left behind by Suwa Myōjin as he leaves the Kamisha and crosses the lake to meet his wife enshrined on the Shimosha on the opposite (northern) shore.[171] Called Omiwatari (御神渡 'the god's crossing' or 'the god's pathway'), the cracks were considered to be a good omen for the coming year.[172] The priests of the Grand Shrine of Suwa traditionally used the crack's appearance to divine the quality of the year's harvest.[173] For the locals, the crack also served as a sign that the frozen lake was safe to walk upon.[174][175] Conversely, the omiwatari's failure to appear at all (明海 ake no umi) or the cracks forming in an unusual way were held to be a sign of bad luck for the year.[173]

Since the late 20th century, the omiwatari has become a much rarer sight than it was in the past due to rising temperatures caused by global warming.[172][176][177]

As god of war

Apparition to Sakanoue no Tamuramaro

The association of Suwa Myōjin with warfare and hunting is most apparent in another legend about his apparition to the general Sakanoue no Tamuramaro during the latter's campaign to subjugate the Emishi of northeastern Japan.[68][178][179] The following summary is based on the version found in the Ekotoba.[180][181][182]

During the reign of Emperor Kanmu, an Emishi chief named Abe no Takamaru (安倍高丸) staged a rebellion against the imperial court. The emperor, in response, appointed Sakanoue no Tamuramaro as Sei-i Taishōgun, sending him to Ōshū to quell the Emishi threat. Knowing that Takamaru cannot be defeated without divine aid, Tamuramaro prays to Suwa Myōjin for victory. As he and his troops were passing by the Ina and Suwa districts of Shinano Province, a warrior riding a dapple horse – Suwa Myōjin in disguise – joins their company.[180][183][182]

Upon arriving at Takamaru's impregnable stronghold by the sea, the horseman from Shinano miraculously splits into five identical mounted warriors (the manifestations of Suwa Myōjin's thirteen divine children), while twenty men dressed in yellow (the god's attendants) appear from out of nowhere. The horsemen and the men in yellow then begin to hold a yabusame (mounted archery) competition over the surface of the sea, which succeeds in luring Takamaru out of hiding. The horseman then blinds Takamaru with his last remaining arrow as the twenty men in yellow proceed to capture and behead him, mounting his head onto a spear.[180][181][182]

On the return journey, the warrior's horse suddenly rises into the air as the rider assumes the aspect of a deity attired in court dress.[179] He then announces to the company his true identity as the god of Suwa and his love of hunting. Tamuramaro questions why the god revels in such an activity that involves taking the lives of sentient beings, to which Suwa Myōjin gives an explanation to the effect that being hunted and killed actually helps sinful and ignorant animals to reach enlightenment. He then bequeaths to Tamuramaro a written dhāraṇī - probably a reference to the Suwa Mishirushibumi[184] - and finally disappears. In accordance with Suwa Myōjin's request, Tamuramaro then petitions the court to institute the religious festivals of the shrines of Suwa.[180][185][182]

Repelling the Mongol invasions

Suwa Myōjin has also been credited with repelling the attempted Mongol invasions of Japan under Kublai Khan.

The Taiheiki recounts a story where a five-colored cloud resembling a serpent (a manifestation of Suwa Myōjin) rose up from Lake Suwa and spread away westward to assist the Japanese army against the Mongols.[lower-alpha 22][186][187][188][189] The Ekotoba recounts a similar anecdote about Suwa Myōjin appearing as a great dragon riding on a cloud in the summer of 1279 (Kōan 2).[lower-alpha 23][190][191]

Analysis

Takeminakata's absence in other Izumo-related contexts

Takeminakata's rather abrupt appearance in the Kojiki's version of the kuni-yuzuri myth has long puzzled scholars, as the god is mentioned nowhere else in the work, including the genealogy of Ōkuninushi's progeny that precedes the kuni-yuzuri narrative proper.[192] Aside from the parallel account contained in the Kuji Hongi (which was itself based on the Kojiki's[193]), he is altogether absent from the Nihon Shoki's version of the myth.[194][195] In addition to this, early sources from Izumo such as the province's Fudoki also fail to mention any god named '(Take)minakata'; neither is there any trace of such a deity being worshipped in Izumo in antiquity.[193]

Pre-modern authors such as Motoori Norinaga tended to explain Takeminakata's absence outside of the Kojiki and the Kuji Hongi by conflating the god with certain obscure deities found in other sources thought to share certain similar characteristics (e.g. Isetsuhiko).[196] While some modern scholars still suppose some kind of connection between the deity and Izumo by postulating that Takeminakata's origins lie either in peoples that migrated from Izumo northwards to Suwa and the Hokuriku region[197] or in Hokuriku itself (a region once under Izumo's sphere of influence), specifically in Echigo Province (modern Niigata Prefecture),[198] others, in light of the aforementioned silence, think it more likely that the connection between Takeminakata and Izumo was an artificial construct by the Kojiki's compilers.[6][199][193]

The Yamato state's expansion into Suwa

Yamato rule is thought to have entered Suwa from the south (the modern districts of Kamiina and Shimoina) somewhere around the latter half of the 6th century.[200] The appearance of corridor-type (横穴式石室 yokoana-shiki sekishitsu) kofun in the region, markedly different from the mounds (thought to be the tombs of influential local priest-chiefs) built on the southern side of Lake Suwa - the site of the Suwa Kamisha - during the 5th-6th centuries, which were characterized by ditches surrounding the burial area, are taken to be the signs of the expansion of the Yamato state in the region.[201][200][202]

The Kuji Hongi[203] mentions a grandson (or descendant) of Kamuyaimimi-no-Mikoto (a son of Emperor Jimmu), Takeiotatsu-no-Mikoto, (建五百建命) who was appointed the governor or kuni no miyatsuko of Shinano (科野国造) during the reign of Emperor Sujin (traditionally dated to the 1st century BCE but most likely somewhere around the 4th century CE[204]).

The Ihon Aso-shi keizu, of disputed historicity, (see above) claims that Takeiotatsu's descendant, Kaneyumi-no-kimi (金弓君), served as toneri (舎人, attendant or palace guard) of the Emperor Kinmei (reigned 539-571) in his palace, the Kanasashi-no-miya (金刺宮) in modern-day Sakurai City, Nara Prefecture, receiving the kabane atai (直) from said emperor.[205] One of Kaneyumi's sons, Mase-gimi (麻背君), who became the kuni no miyatsuko of Shinano (reestablished for the first time in a few generations), had two sons: the first, Kuratari (倉足), was appointed the administrator (kōri no kami/hyōtoku) of Suwa district (諏訪評督), while the second, Otoei or Kumako (see above), became the priest or ōhōri of the god of Suwa (諏訪大神大祝).[206][207][208]

Turnover of authority

The Suwa region during the late Yayoi period was thought to have been originally populated by autonomous village communities, the chiefs of which also functioned as the ritual heads of their respective communities. These villages were eventually united under a single leader who governed the religious practices of these communities, which were centered around the worship of the god(s) Mishaguji,[209][193] spirits that were thought to descend upon and inhabit natural objects like trees or rocks and function as life-giving guardians of local communities.[210][211]

The legend of the battle between the god Moreya and Suwa Myōjin (see above) may suggest that the advent of Yamato rule in Suwa during the late 6th century was initially met with resistance, especially on the southern side of Lake Suwa, the stronghold of the indigenous Mishaguji cult.[200] This intransigence was ultimately quelled, and politico-religious rule over the region was soon turned over from an indigenous lineage of priest-chiefs, what would later become known as the Moriya clan (守矢氏), to Yamato-appointed authorities.[212][202]

It was probably around this time that the shamanistic concept of the misogi-hōri/ōhōri, the physical manifestation of an invisible divinity, came into being as a way to subsume native religious practices into the Yamato belief system.[202] The office of ōhōri was probably meant to rival that of the okō (神使), a young boy (or boys) who became vessels for Mishaguji during religious rituals who later became interpreted as representatives of the ōhōri.[213][214] The priest-chieftain of the Moriya clan meanwhile was integrated into the new system as the kan no osa/jinchō (神長) or jinchōkan (神長官), the sole priest who could call upon Mishaguji.[215]

The Moriya's submission to and cooperation with the new system enabled the local Mishaguji cult to survive underneath it: while officially subservient to the ōhōri, in reality the Moriya jinchōkan, who presided over religious rites, continued to hold actual power while the ōhōri was but a symbolic figurehead.[216] The ōhōri's investiture ceremony even involved the jinchōkan summoning Mishaguji to enter the young candidate's body during the ritual; it is only by being possessed by Mishaguji that the candidate became a god himself.[217][213]

The rise of Takeminakata

Both the Aso and the Suwa clan genealogies refer to the foundation of a sanctuary (社壇) on the southern side of Lake Suwa (where the Suwa Kamisha currently stands) by Otoei/Kumako, claimed to be in both sources as the first ōhōri, where the "great god of Suwa" (諏訪大神) and other divinities were worshipped in the third month of the second year of the Emperor Yōmei (587 CE).[lower-alpha 24][218][219]

In 691 CE, the Nihon Shoki refers to envoys of the Yamato court going to Shinano Province to worship "the gods of Suwa and Minochi"(須波水内等神). This reference suggests that the cult of the ōhōri and the sanctuary at Suwa had become established and influential enough to attract attention from the Yamato imperial court.[220][221]

Just twenty years after this, the name '(Take)minakata(tomi)' - which may have originated as a name for (the deity manifest in) the ōhōri[222] - appears in the historical record for the first time in the Kojiki (711–712 CE).[223] Due to the absence of Takeminakata in other sources dealing with Izumo, it is thought that the god was interpolated into the Kojiki by its chief compiler, Ō no Yasumaro, who may have either adapted a preexisting myth or created one outright.[224][225][226][223]

Scholars believe various factors were at play for Takeminakata's introduction in the Kojiki's narrative - one being that Yasumaro's clan, the Ō (太氏; also written variously as 多, 意富, or 於保), were distantly related to the clan who ruled the Suwa region, the Kanasashi-no-toneri (金刺舎人), in that both were supposedly descendants of Kamuyaimimi-no-Mikoto:[227][228] Takeminakata's inclusion in the Kojiki was thus a means to advertise the 'new' god of the Kanasashi.[229] Another possible reason was the special interest Emperor Tenmu (the one who commissioned both the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki) showed to Shinano: the Nihon Shoki speaks of Tenmu sending envoys to inspect the province "perhaps with the object of having a capital there" in the thirteenth year of his reign.[230][231]

While the Kojiki does not yet explicitly mention the worship of Takeminakata in Suwa, by the following century, we see the name applied to the god worshipped in what is now the Grand Shrine of Suwa: aside from the Kuji Hongi's (807-936 CE) reference to Takeminakata being enshrined in 'Suwa Shrine in Suwa District'[19][18] the Shoku Nihon Kōki mentions the deity 'Minakatatomi-no-Kami of Suwa District, Shinano Province' (信濃国諏訪郡 ... 南方刀美神) being promoted from rankless (无位) to junior fifth rank, lower grade (従五位下) by the imperial court in the year 842 CE (Jōwa 9).[lower-alpha 25][232][233][234][235]

During the 850-60s, Takeminakata and his shrine rose very rapidly in rank (Montoku Jitsuroku, Nihon Sandai Jitsuroku), being promoted to the rank of junior fifth, upper grade (従五位上) in 850 (Kashō 3),[lower-alpha 26][236] to junior third (従三位) in 851 (Ninju 1),[lower-alpha 27][237] to junior (従二位)[lower-alpha 28] and then senior second (正二位)[lower-alpha 29] in 859 (Jōgan 1),[238] and finally to junior first rank (従一位) in 867 (Jōgan 9).[lower-alpha 30][239][234] The influence of the Kanasashi-no-toneri clan is thought to be behind the deity's sudden progress in rank.[235][240]

After a few decades, the 'Register of Deities' (神名帳 Jinmyōchō) section of the Engishiki (927) speaks of the 'Minakatatomi Shrine(s)' (南方刀美神社) as enshrining two deities and being the two major ('eminent') shrines of Suwa district.[lower-alpha 31][241] By 940 (Tengyō 3), the deity had been promoted to the highest rank of senior first (正一位).[235][242]

Takeminakata and Suwa Myōjin

While the above sources (compiled by the imperial court in Heian-kyō) apply the name '(Take)minakata' to the god of Suwa Grand Shrine, within Suwa itself the god was never worshipped or referred to under that name.[235] A testament to the enduring influence of the pre-Yamato Mishaguji belief system is the fact that many of the religious ceremonies of the Suwa Kamisha and surviving descriptions of said rituals feature Mishaguji as the focus of worship rather than 'Takeminakata', who never appears at all in these rites.[243] Even local stories that feature the god of the Suwa Kamisha recorded in medieval texts (see above) refer to the deity in question with such generic terms as sonshin (尊神 'revered deity') or myōjin (明神 'manifest deity').[244] Takeminakata's portrayal in the Kojiki and the Kuji Hongi as one who suffered a humiliating defeat was apparently seen as something of an embarrassment during the Middle Ages, leading to the appearance of alternative stories which portray Suwa Myōjin's origins in a more positive light such as the Kōga Saburō legend.[103]

The earliest documents from within (or connected to) Suwa to explicitly call Suwa Myōjin 'Takeminakata' or identify him with the god from Izumo are the Monoimi no rei (1238) - which refers in passing to Suwa Myōjin's name being 'Takeminakata Myōjin' (武御名方明神)[75] - and the Suwa Daimyōjin Ekotoba (1356), the latter creatively retelling the Izumo kuni-yuzuri legend as found in the Kuji Hongi by omitting any mention of Takeminakata being defeated.[245][30] The Ekotoba's popularity among a wide audience that included the priestly families of the Suwa Grand Shrine seems to have contributed to eventually cementing the identification of Suwa Myōjin with the Takeminakata of the official histories: Ōkuninushi's son who came to Suwa from Izumo.[235]

Consort and Offspring

Yasakatome

Suwa Myōjin's spouse is the goddess Yasakatome-no-Kami (八坂刀売神), most often considered to be the deity of the Lower Shrine of Suwa or the Shimosha.[246] Unlike the relatively well-documented Suwa Kamisha, very little concrete information is available regarding the origins of the Shimosha and its goddess.[247]

Yasakatome's first historical attestation is in the Shoku Nihon Kōki, where the goddess is given the rank of junior fifth, lower grade (従五位下) by the imperial court in the tenth month of Jōwa 9 (842 CE), five months after the same rank was conferred on Takeminakata.[lower-alpha 32][232][248] As Takeminakata rose up in rank, so did Yasakatome,[249][236][237][238] so that by 867 CE, Yasakatome had been promoted to senior second (正二位).[239] The goddess was finally promoted to senior first rank (正一位) in 1074 (Jōhō 1).[240]

Stories and claims about the goddess are diverse and contradictory. Regarding her parentage for instance, the lore of Kawaai Shrine (川会神社) in Kitaazumi District identifies Yasakatome as the daughter of Watatsumi, god of the sea,[250] which has been seen as hinting to a connection between the goddess and the seafaring Azumi clan (安曇氏).[251] Another claim originating from sources dating from the Edo period is that Yasakatome was the daughter of Ame-no-yasakahiko (天八坂彦命), a god recorded in the Kuji Hongi as one of the companions of Nigihayahi-no-Mikoto when the latter came down from heaven.[252][253][251]

The ice cracks that appear on Lake Suwa during cold winters, the omiwatari (see above) are reputed in folklore to be caused by Suwa Myōjin's crossing the frozen lake to visit Yasakatome.[171]

Princess Kasuga

The Kōga Saburō legend identifies the goddess of the Shimosha with Saburō's wife, whose name is given in some variants of the story as 'Princess Kasuga' (春日姫 Kasuga-hime).[102][103]

Children

In Suwa, a number of local deities are popularly considered to be the children of Suwa Myōjin and his consort. Ōta (1926) lists the following gods:[254]

.jpg)

- Hikokamiwake-no-Mikoto (彦神別命)

- Tatsuwakahime-no-Kami (多都若姫神)

- Taruhime-no-Kami (多留姫神)

- Izuhayao-no-Mikoto (伊豆早雄命)

- Tateshina-no-Kami (建志名神)

- Tsumashinahime-no-Kami (妻科姫神)

- Ikeno'o-no-Kami (池生神)

- Tsumayamizuhime-no-mMikoto (都麻屋美豆姫命)

- Yakine-no-Mikoto (八杵命)

- Suwa-wakahiko-no-Mikoto (洲羽若彦命)

- Katakurabe-no-Mikoto (片倉辺命)

- Okihagi-no-Mikoto (興波岐命)

- Wakemizuhiko-no-Mikoto (別水彦命)

- Moritatsu-no-Kami (守達神)

- Takamori-no-kami (高杜神)

- Enatakemimi-no-Mikoto (恵奈武耳命)

- Okutsuiwatate-no-Kami (奥津石建神)

- Ohotsuno-no-Kami (竟富角神)

- Ōkunugi-no-Kami (大橡神)

Claimed descendants

Suwa clan

The Suwa clan who once occupied the position of head priest or ōhōri of the Suwa Kamisha traditionally considered themselves to be descendants of Suwa Myōjin/Takeminakata,[255][256][257] although historically they are probably descended from the Kanasashi-no-toneri clan appointed by the Yamato court to govern the Suwa area in the 6th century (see above).[258]

Other clans

The Suwa ōhōri was assisted by five priests, some of whom were also considered to be descendants of local deities related to Suwa Myōjin/Takeminakata.[256] One clan, the Koide (小出氏), the original occupants of the offices of negi-dayū (禰宜大夫) and gi-no-hōri (擬祝), claimed descent from the god Yakine.[259][260] A second clan, the Yajima (八島(嶋)氏 or 矢島氏), which served as gon-no-hōri (権祝), considered the god Ikeno'o to be their ancestor.[261][262][263][264]

Worship

Shrines

As the gods of the Grand Shrine of Suwa, Suwa Myōjin/Takeminakata and Yasakatome also serve as the deities of shrines belonging to the Suwa shrine network (諏訪神社 Suwa-jinja) all over Japan.

As god of wind and water

The Nihon Shoki's record of Yamato emissaries worshipping the god of Suwa alongside the gods of Tatsuta Shrine - worshipped for their power to control and ward off wind-related disasters such as droughts and typhoons[265][266][267] - implies that the Yamato imperial court recognized the deity as a god of wind and water during the late 7th century.[268][269] One theory regarding the origin of the name '(Take)minakata' even supposes it to derive from a word denoting a body of water (水潟 minakata; see above).[11][10][270]

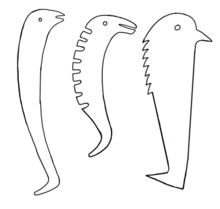

Snake-shaped iron sickle blades called nagikama (薙鎌) were traditionally used in the Suwa region to ward off strong winds, typhoons and other natural disasters; it was once customary for nagikama to be attached to wooden staves and placed on one corner of the rooftop of the house during the autumn typhoon season.[271][272][273] Nagikama are also traditionally hammered onto the trees chosen to become the onbashira of the Suwa Kamisha and Shimosha some time before these are actually felled.[274] In addition to these and other uses, the blades are also distributed to function as shintai for branch shrines of the Suwa shrine network.[271][275]

Association with snakes and dragons

Suwa Myōjin's association with the snake or the dragon in many stories featuring the god such as the Kōga Saburō legend (see 'Legends of Suwa Myōjin' above) might be related to his being considered as a deity presiding over wind and water, due to the association of dragons with winds and the rain in Japanese belief.[276][277] (See also mizuchi.)

Under shinbutsu-shūgō

During the Middle Ages, under the then-prevalent synthesis of Buddhism and Shinto, Suwa Myōjin was identified with the bodhisattva Samantabhadra (Fugen),[278][279] with the goddess of the Shimosha being associated with the thousand-armed form of the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara (Senju Kannon).[280] During the medieval period, Buddhist temples and other edifices were erected on the precincts of both shrines, including a stone pagoda called the Tettō (鉄塔 "iron tower") - symbolizing the legendary iron tower in India where, according to Shingon tradition, Nagarjuna was said to have received esoteric teachings from Vajrasattva (who is sometimes identified with Samantabhadra) - and a sanctuary to Samantabhadra (普賢堂 Fugendō), both of which served at the time as the Kamisha's main objects of worship.[155]

With the establishment of State Shinto after the Meiji Restoration in 1868 and the subsequent separation of Buddhism and Shinto, the shrine monks (shasō) attached to Buddhist temples in the Suwa shrine complex were laicized, with Buddhist symbols and structures being either removed or destroyed; Buddhist ceremonies performed in both the Kamisha and the Shimosha, such as the yearly offering of the Lotus Sutra to Suwa Myōjin (involving the placing of a copy of the sutra inside the Tettō), were discontinued.[281]

As god of hunting

Suwa Myōjin is also worshipped as a god of hunting; not surprisingly, some of the Kamisha's religious ceremonies traditionally involve(d) ritual hunting and/or animal sacrifice.

For instance, the Frog Hunting Ritual (蛙狩神事 kawazugari shinji) held every New Year's Day involves the shooting (or rather, piercing) of frogs captured from a sacred river or stream within the Kamisha's precincts with miniature arrows.[282][283][284] This ritual - which has come under harsh criticism from local activists and animal rights groups for its perceived cruelty to the frogs involved[285][286] - was traditionally performed to secure peace and a bountiful harvest for the coming year.[282]

Another festival, the Ontōsai (御頭祭) or the Tori no matsuri (酉の祭, so called because it was formerly held on the Day of the Rooster) currently held every April 15, feature the offering of seventy-five stuffed deer heads (a substitute for freshly cut heads of deer used in the past), as well as the consumption of venison and other game such as wild boar or rabbit, various kinds of seafood and other foodstuffs by the priests and other participants in a ritual banquet.[287][288][289][290][291]

One of the Suwa Kamisha's hunting festivals, the Misayama Festival (御射山祭), formerly held in a field - the kōya (神野 'the god's plain') - at the foot of the Yatsugatake Mountains for five days (from the 26th to the 30th of the seventh month),[lower-alpha 33] was one of the grandest festivals in Suwa during the Kamakura period, attracting many of the samurai class from all across Japan who engaged in displays of mounted archery, bouts of sumo wrestling and falconry as part of the festivities, as well as people from all walks of life.[293][294][295] The Shimosha also held its own Misayama Festival at the same time as the Kamisha (albeit in a different location), in which various warrior clans also participated.[296][297]

Suwa Myōjin's association with the mountains and hunting is also evident from the description of the ōhōri as sitting upon a deer hide (the deer being an animal thought to be sacred to Suwa Myōjin) during the Ontōsai ritual as practiced during medieval times.[298][299]

Suwa Myōjin and meat eating

At a time when slaughter of animals and consumption of meat was frowned upon due to Mahayana Buddhism's strict views on vegetarianism and the general Buddhist opposition against the taking of life, the cult of Suwa Myōjin was a unique feature in the Japanese religious landscape for its celebration of hunting and meat eating.[300]

A four-line verse attached to the Kōga Saburō legend popularly known as the Suwa no kanmon (諏訪の勘文) encapsulates the justification of meat eating within a Buddhist framework: by being eaten by humans and 'dwelling' inside their bodies, ignorant animals could achieve enlightenment together with their human consumers.[301][302]

業尽有情 Gōjin ujō

雖放不生 Suihō fushō

故宿人天 Koshuku ninten

同証仏果 Dōshō bukka[102][303]

Sentient beings who have exhausted their karma:

Even if one sets (them) free, (they) will not live (for long);

Therefore (have them) dwell within humans and gods

(That they may) as well achieve Buddhahood

The Kamisha produced special talismans (鹿食免 kajiki-men "permit to eat venison") and chopsticks (鹿食箸 kajiki-bashi) that were held to allow the bearer to eat meat.[304][305][306][307] Since it was the only one of its kind in Japan, the talisman was popular among hunters and meat eaters.[256] These sacred licenses and chopsticks were distributed to the public both by the priests of the Kamisha as well as wandering preachers associated with the shrine known as oshi (御師), who preached the tale of Suwa Myōjin as Kōga Saburō as well as other stories concerning the god and his benefits.[256][307]

As war god

Suwa Myōjin is also considered to be a god of war, one of a number of such deities in the Japanese pantheon. Besides the legend of the god's apparition to Sakanoue no Tamuramaro (see above), the Ryōjin Hishō compiled in 1179 (the late Heian period) also attest to the worship of the god of Suwa in the capacity of god of warfare at the time of its compilation, naming the shrine of Suwa among famous shrines to martial deities in the eastern half of the country.

These gods of war live east of the barrier:[lower-alpha 34]

Kashima, Katori, Suwa no Miya, and Hira Myōjin;

also Su in Awa, Otaka Myōjin in Tai no Kuchi,

Yatsurugi in Atsuta, and Tado no Miya in Ise.

During the Kamakura period, the Suwa clan's association with the shogunate and the Hōjō clan helped further cement Suwa Myōjin's reputation as a martial deity.[310] The shrines of Suwa and the priestly clans thereof flourished under the patronage of the Hōjō, which promoted devotion to the god as a sign of loyalty to the shogunate.[310] Suwa branch shrines became numerous all across Japan, especially in territories held by clans devoted to the god (for instance, the Kantō region, traditional stronghold of the Minamoto (Seiwa Genji) clan).[311]

The Takeda clan of Kai Province (modern Yamanashi Prefecture) were devotees of Suwa Myōjin, its most famous member, the Sengoku daimyō Takeda Shingen being no exception.[312][313] His devotion is visibly evident in some of his war banners, which bore the god's name and invocations such as Namu Suwa Nangū Hosshō Kamishimo Daimyōjin (南無諏方南宮法性上下大明神 'Namo Dharma-Nature Daimyōjin of the Suwa Upper and Lower Shrines').[16] The iconic horned helmet with the flowing white hair commonly associated with Shingen, popularly known as the Suwa-hosshō helmet (諏訪法性兜 Suwa-hosshō-(no)-kabuto), came to be reputed in some popular culture retellings to have been blessed by the god, guaranteeing success in battle to its wearer.[314][315] Shingen also issued an order for the reinstitution of the religious rites of both the Kamisha and the Shimosha in 1565.[316][317]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The precise meaning of Nangū (南宮, lit. 'Southern Shrine'), another term used to refer to the shrine of Suwa during the medieval period,[13] is uncertain: suggestions include the name being a reference to the geographical location of the Suwa Kamisha (Upper Shrine) on the south of Lake Suwa, it having a supposed connection to Nangū Shrine in modern Gifu Prefecture, or it deriving from 'Minakata', here understood as meaning 'south(ern)' (南方).[14]

- ↑ Ame-no-Torifune in the Kojiki, Futsunushi in the Nihon Shoki and the Kuji Hongi

- ↑ 「天照太神ミコトノリシテ経津主ノ総州香取社神武甕槌ノ常州鹿島社神二柱ノ神ヲ出雲国ニ降タテマツリテ、大己貴雲州杵築・和州三輪ノ命ニ問テノタマハク、葦原ノ中津国者我御子の知ラスヘキ国ナリ。汝マサニ此国ヲモテ天ノ神ニ奉ンヤ、大己貴ノ命申サク、我子事代主摂州長田社・神祇官第八ノ神ニ問テ返事申サント申、事代主神申サク、我父ヨロシクマサニサリ奉ルヘシ。ワレモ我タカウヘカラスト申。又申ヘキ子アリヤ、又我子建御名方諏訪社ノ神、千引ノ石ヲ手末ニサヽケテ来テ申サク、是我国ニキタリテ、シノヒテカクイフハ、シカウシテ力クラヘセント思、先ソノ御手ヲ取テ即氷ヲ成立、又剣ヲ取成、科野ノ国洲羽ノ海ニイタルトキ、当御名方ノ神申サク、ワレ此国ヲ除者他処ニ不行云々、是則当社垂迹ノ本縁也。」[31]

- ↑ 「祝は神明の垂迹の初。御衣を八歳の童男にぬぎきせ給ひて。大祝と称し。我において体なし。祝を以て躰とすと神勅ありけり。是則御衣祝有員神氏の始祖なり。」[45]

- ↑ 「乙頴 (諏訪大神大祝):一名神子、又云、熊古 生而八歳、御名方富命大神化現脱着御衣於神子勅曰、吾無体以汝為体、盤余池辺大宮朝二年丁未三月搆壇于湖南山麓、祭諏訪大明神及百八十神、奉千代田刺忌串斎之」[60]

- ↑ Literally: 'hid himself'

- ↑ 「国造九世之孫、五百足、常時敬事于尊神、一日夢有神告、汝妻兄弟部既姙、身分娩必挙于男子、成長欲吾将有憑之、汝宜鍾愛矣夢覚而後、語之妻兄弟部、兄弟部亦同夢恠、且慎、後果而産男子因名神子、亦云熊子、神子八歳之時、尊神化現、脱着御衣於神子、吾無体以汝為体、有神勅隠御体矣、是則御衣着祝神氏有員之始祖也、用命天皇御宇二年、神子搆社壇于湖南山麓、其子神代、其子弟兄子、其子国積、其子猪麿、其子狭田野、其子高牧、亦云豊麿、其子生足、其子繁魚、其子豊足、亦云清主、其子有員、亦云武麿、」[63]

- ↑ This place name appears as one of the sixteen Mahājanapadas in Kumārajīva's translation of the Humane King Sutra.[72][73]

- ↑ (Version 1[71]) 「當社明神者、遠異朝雲、分近南浮之巷狹、其名武御名方明神申。去者、和光古尋、波提國主〆文月未ノ比鹿野苑之御狩、守洩逆臣奉制、遁其難、廣大慈悲之得名給。(...) 南方波斯國御幸成、惡龍降伏シ、萬民救治、彼國諏方皇帝申セリ。到東方金色山、善苗植テ佛道成給。其後我朝移給、接州蒼海顯、垂跡ヲ三韓西戎之逆浪、諏テハ西宮顯ル、又ハ豐前高山麓光和、百王南面之護、寶祚誓給南宮申也、終ハ勝地信濃國諏方郡垂跡 ...」

(Version 2[76]) 「當社明神者、遠分異朝雲、近交南浮塵給、申其名建御名方明神、去ハ和光之古ヲタツヌル、波提國ノ王トシテ文月未比鹿野苑御狩ノ時、奉襲守屋逆臣カ其難ヲノカレ、廣大慈悲之得名給。(...) 南方幸波斯國、降伏惡龍、救萬民、彼國ヲ治メ、爲陬波皇帝。東方至金色山、殖善苗成佛給。其後移我朝給テ、接州蒼海邊ニ垂迹、鎭三韓西戎之逆浪、表西宮、又ハ濃州高山ノ麓ニ和光、守百王南面之寶祚誓玉申南宮、終ニ卜勝地於信濃諏方郡垂跡給 ...」- (When) the god (myōjin) of this shrine... as king of the land of 'Hadai', went to hunt at Deer Park in the month of Fumizuki, during the hour of the sheep, subdued the renegade Moriya, he escaped from the calamity and received the name 'the immensely compassionate one'...

- Going south (sic) to the land of Persia, he defeated an evil dragon, rescuing its people. He ruled that land as Emperor Suwa.

- Arriving at a golden mountain in the east, he cultivated the seedling of virtue and attained buddhahood. Afterwards he moved to our country, appearing in the sea of Sesshū and (pacifying) the chaos of (lit. 'the rough sea of') the Xirong (of/and the) three Han (kingdoms).

- He then (deliberated to) appear in Nishinomiya, and at the foot of (Mount) Takayama in Nōshū (or: Buzen Province) he dimmed his radiance (...) Finally he manifested in the goodly district of Suwa in Shinano ...

- ↑ 「扨も此御狩の因縁をたづぬれば、大明神昔天竺波提國の王たりし時、七月廿七日より同卅日にいたるまで鹿野園に出で狩をせさせ給ひたる時、美教と云亂臣忽に軍を率して王を害し奉らんとす。其時王金鈴を振て、蒼天に仰て八度さけびてのたまはく、『我今逆臣の為に害せられむとす、狩る所の畜類全く自欲の爲にあらず。佛道を成ぜしめむが爲也。是若天意にかなはば、梵天我をすくひたまへ』と。其時梵天眼を以て是を見て、四大天王に勅して金剛杖を執て群黨を誅せしめ給ひにけり。今の三齋山、其儀をうつさるゝ由傳たり。(...)爰に知ぬ、神明慈悲の畋獵は郡類濟度の方便なりと云事を。」[78]

- ↑ The 'seal' referred to here is interpreted to be either the Upper Shrine's sacred seal made of deer antler[87] or the Mishirushibumi itself.[88]

- ↑ 「陬波大王 限甲午隠身、陬波与甲午 印文同一物三名。」[89]

- ↑ 「一、大明神甲午仁有御誕生甲午仁隠御身給フ

一、続旦(ソクタン)大臣ト申ハ大明神ノ叔父御前自リ天竺御同道、大明神御体ヲ隠サセ給シ時御装束ヲ奉抜著(ヌキキセ)彼大臣給テ号御衣木(ミソキ)法理ト 我之躰以法理ヲ躰トセヨトハ誓給シ也」[94] - ↑ 「一、御衣木法理殿御実名ハ者有員云〻」[97]

- ↑ 「一 守屋山麓御垂跡事

右謹檢舊貫、當砌昔者守屋大臣之所領也、大神天降御之刻、大臣者奉禦明神之居住、勵制止之方法、明神者廻可爲御敷地之祕計、或致諍論、或及合戰之處、兩方難決雌雄、爰明神者持藤鎰、大臣者以鐵鎰、懸此所引之、明神即以藤鎰令勝得軍陣之諍論給、而間令追罰守屋大臣、卜居所當社以來、遙送數百歲星霜、久施我神之稱譽天下給、應跡之方々是新哉、明神以彼藤鎰自令植當社之前給、藤榮枝葉號藤諏訪之森、毎年二ヶ度御神事勤之、自尓以來以當郡名諏方、爰下宮者當社依夫婦之契約示姫大明神之名、然而當大明神、若不令追出守屋給者、爭兩者卜居御哉、自天降之元初爲本宮之條炳焉者哉、」[68] - ↑ 「抑此藤島の明神と申は。尊神垂迹の昔。洩矢の惡賊神居をさまたげんとせし時。洩矢は鐵輪を持してあらそひ。明神は藤枝を取りて是を伏し給ふ。終に邪輪を降して正法を興す。明神誓を發て。藤枝をなげ給しかば。則根をさして枝葉をさかへ花蘂あざやかにして。戰場のしるしを萬代に殘す。藤島の明神と號此故也。」

- ↑ Both Taokihooi and Hikosachi - identified as two distinct individuals - appear in the Nihon Shoki[129][130] and the Kogo Shūi[131] as ancestors of the Inbe clan (忌部氏).

- ↑ 「正一月日之蝦蟆狩之事 蝦蟆神成 大荒神 惱乱天下時、大明神彼ヲ退治御座し時、四海静謐之間、陬波卜云字ヲ波陬なりと讀り、口傅多し」(Monoimi no rei)

- Concerning the Frog Hunting (Ceremony) of New Year's Day.

- When the toad god turned into a greatly violent deity and caused trouble to all under heaven, the Daimyōjin subdued it; the four seas then became tranquil.

- The term 'Suwa' (陬波) means (lit. 'is read as') "a corner wave" (namishizuka, i.e. a wave lapping onto the sea's edge[138]). Many oral legends exist [about this event].

- ↑ 「一、陬波ト申事ナミシツカナリトヨメリ 蝦蟆カニタ神カエルノ事ナリ荒神惱ト天下時、大明神退治之御坐時 四海静謐之間 陬波卜云〻 口傅在之」(Suwa Shichū)

- ↑ 「一、御座石ト申ハ正面之内二在リ、件之蝦蟆神之住所之穴通龍宮城エ、退治蝦蟆神、破穴以石塞其ノ上坐玉シ間、名ヲ石之御座ト申也 口傅在之」(Monoimi no rei)

- The so-called Goza-ishi is located within the Shōmen (i.e. the Kamisha's inner sanctum).

- The toad god lived in a hole that led to the dragon king's palace (Ryūgū-jō). When [the Daimyojin] subdued the toad god, he blocked the hole with a stone and sat on it.

- The stone is thus named ishi no goza ('stone seat'). This [story] exists in oral legends.

- ↑ 「石御座ト申ハ 件蝦蟆神 住所之穴通龍宮城 退治蝦蟆神彼穴 以石ヲフタキテ 其上ニ坐シ給間 石御座リ申也 口傅在之」(Suwa Shichū)

- ↑ 「如此御祈祷已に七日満じける日、諏訪の湖の上より、五色の雲西に聳き、大蛇の形に見へたり。八幡御宝殿の扉啓けて、馬の馳ちる音、轡の鳴音、虚空に充満たり。日吉の社二十一社の錦帳の鏡動き、神宝刃とがれて、御沓皆西に向へり。住吉四所の神馬鞍の下に汗流れ、小守・勝手の鉄の楯己と立て敵の方につき双べたり。」

- On the seventh day, when the Imperial devotions were completed, from Lake Suwa there arose a cloud of many colours, in shape like a great serpent, which spread away towards the west. The doors of the Temple-treasury of Hachiman flew open, and the skies were filled with a sound of galloping horses and of ringing bits. In the twenty-one shrines of Yoshino the brocade-curtained mirrors moved, the swords of the Temple-treasury put on a sharp edge, and all the shoes offered to the god turned towards the west. At Sumiyoshi sweat poured from below the saddles of the four horses sacred to the deities, and the iron shields turned of themselves and faced the enemy in a line. ... (trans. William George Aston)

- ↑ 「後宇多院御宇弘安二年己卯季夏の天。當社神事時。日中に變異あり。大龍雲に乘じて西に向。參詣諸人眼精の及所そこはかとなく。雲間殊にひはたの色ひらひらと見ゆ。一龍か又數龍か。首尾は見えず。何樣にも明神大身を現じて。本朝贔屓の力を入れまします勢なり。」

- ↑ 「乙頴 (諏訪大神大祝):一名神子、又云、熊古 生而八歳、御名方富命大神化現脱着御衣於神子勅曰、吾無体以汝為体、盤余池辺大宮朝二年丁未三月構壇于湖南山麓、祭諏訪大明神及百八十神、奉千代田刺忌串斎之」

- ↑ 「丁未。奉授信濃國諏方郡无位勳八等南方刀美神從五位下。」

- ↑ 「己未。信濃國御名方富命神、健御名方富命前八坂刀賣命神、並加從五位上。」

- ↑ 「乙丑。進信濃國建御名方富命、前八坂刀賣命等兩大神階、加從三位。」

- ↑ 「廿七日甲申。 (...) 信濃國正三位勳八等建御名方冨命神從二位。」

- ↑ 「十一日丁酉。(...) 授信濃國從二位勳八等建御名方富命神正二位。」

- ↑ 「十一日辛亥。信濃國正二位勳八等建御名方富命神進階從一位。」

- ↑ 「諏方郡二座 並大 南方刀美神社二座 名神大」

- ↑ 「奉授安房國從五位下安房大神正五位下。无位第一后神天比理刀咩命神。信濃國无位健御名方富命前八坂刀賣神。阿波國无位葦稻葉神。越後國无位伊夜比古神。常陸國无位筑波女大神竝從五位下。」

- ↑ Currently three days: from the 26th to the 28th of August.[292]

- ↑ During the Heian period, the expression 'east of the barrier' (関の東 seki-no-hi(n)gashi, whence derives the term 関東 Kantō) referred to the provinces beyond the checkpoints or barrier stations (関 seki) at the eastern fringes of the capital region, more specifically the land east of the checkpoint at Ōsaka/Ausaka Hill (逢坂 'hill of meeting', old orthography: Afusaka; not to be confused with the modern city of Osaka) in modern Ōtsu, Shiga Prefecture.[308] By the Edo period, Kantō was reinterpreted to mean the region east of the checkpoint in Hakone, Kanagawa Prefecture.

- ↑ 「関より東(ひむかし)の軍神(いくさがみ)、鹿島・香取(かんどり)・諏訪の宮、また比良(ひら)の明神、安房の洲(す)滝(たい)の口や小鷹明神、熱田に八剣(やつるぎ)、伊勢には多度(たど)の宮。」

References

- ↑ Motoori, Norinaga (1764–1798). 古事記伝 (Kojiki-den), vol. 14.

- ↑ Motoori, Norinaga (1937). 古事記傳 (Kojiki-den), vol. 14 in Motoori Toyokai (ed.), 本居宣長全集 (Motoori Norinaga Zenshū), vol. 2. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan. p. 675. (Original work written 1764–1798)

- 1 2 3 Chamberlain, Basil (trans.) (1882). Section XXXII.—Abdication of the Deity Master-of-the-Great-Land. A translation of the "Ko-ji-ki" or Records of Ancient Matters. Yokohama: Lane, Crawford & Co.

- ↑ Ōta (1926). p. 8.

- ↑ Ōwa (1990). pp. 214–216.

- 1 2 3 Yoshii, Iwao, "Takeminakata-no-Kami (建御名方神)", Encyclopedia Nipponica, 14, Shōgakukan, ISBN 978-4-09-526114-0

- ↑ Matsuoka, Shizuo (1936). Minzokugaku yori mitaru Azuma-uta to Sakimori-uta (民族學より見たる東歌と防人歌). Ōokayama-shoten. pp. 197–199.

- ↑ Yamaguchi, Yoshinori and Kōnoshi, Takamitsu (eds.) (1997). Shinpen nihon koten bungaku zenshū, vol. 1. Kojiki (新編日本古典文学全集 (1) 古事記). Shōgakukan. pp. 107–111. ISBN 978-4-09-658001-1.

- 1 2 Muraoka (1969). pp. 14–16.

- 1 2 3 Okada, Yoneo (1966). Zenkoku jinja saijin goshintokki (全国神社祭神御神徳記), quoted in Muraoka (1969). p. 14.

- 1 2 3 Miyasaka, Mitsuaki (1987). "Kyodai naru kami no kuni. Suwa-shinko no tokushitsu (強大なる神の国―諏訪信仰の特質)." In Ueda; Gorai; Ōbayashi; Miyasaka, M.; Miyasaka, Y. p. 31.

- ↑ Tomiku, Takashi (1970). Himiko (卑弥呼). Gakuseisha. p. 48, cited in Kanai (1982). p. 6.

- ↑ Tanigawa, ed. (1987). pp. 130-131.}}

- ↑ Miyachi (1931b). pp. 21–24.

- ↑ Inoue, Takami (2003). "The Interaction between Buddhist and Shinto Traditions at Suwa Shrine". In Rambellli, Fabio; Teuuwen, Mark (ed.). Buddhas and Kami in Japan: Honji Suijaku as a Combinatory Paradigm. Routledge. pp. 346–349.

- 1 2 "山梨の文化財ガイド (Guide to Cultural Assets of Yamanashi)". Official website of Yamanashi Prefecture.

- ↑ Miyachi (1931b). pp. 86–89.

- 1 2 "先代舊事本紀卷第四". 私本 先代舊事本紀.

- 1 2 3 先代舊事本紀 巻第四 (Sendai Kuji Hongi, book 4), in Keizai Zasshisha, ed. (1898). 国史大系 第7巻 (Kokushi-taikei, vol. 7). Keizai Zasshisha. pp. 243–244.

- ↑ Grumbach (2005). pp. 153-154.

- ↑ "ミシャグジ (Mishaguji)". 日本の神様辞典 (Nihon no Kamisama Jiten).

- ↑ Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (1995). p. 689.

- ↑ Tanigawa, ed. (1987). p. 185.

- ↑ Chamberlain (1882). Section XXVI.—The Deities the August Descendants of the Deity Master-of-the-Great-Land

- ↑ Chamberlain (1882). Section XXIV.—The Wooing of the Deity-of-Eight-Thousand-Spears.

- 1 2 "先代舊事本紀卷第三". 私本 先代舊事本紀.

- ↑ J. Hackin (1932). Asiatic Mythology: A Detailed Description and Explanation of the Mythologies of All the Great Nations of Asia. Asian Educational Services. p. 395. ISBN 978-81-206-0920-4.

- ↑ Jean Herbert (18 October 2010). Shinto: At the Fountainhead of Japan. Routledge. p. 437. ISBN 978-1-136-90376-2.

- ↑ Michael Ashkenazi (1 January 2003). Handbook of Japanese Mythology. ABC-CLIO. pp. 267–268. ISBN 978-1-57607-467-1.

- 1 2 Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai (諏訪市史編纂委員会), ed. (1995). Suwa Shishi, vol. 1 (諏訪市史 上巻 原始・古代・中世). Suwa. pp. 685, 689.

- ↑ Suwa Daimyōjin Ekotoba, in Kanai (1982). p. 219.

- ↑ Yamashita (2006). p. 9.

- ↑ "佐原諏訪神社(御手形神社) 下伊那郡豊丘村佐原". 諏訪大社と諏訪神社(附・神社参拝記). 八ヶ岳原人.

- ↑ "国護りと天孫降臨の神話ー御手形石ー". JA Minami Shinshu official website.

- ↑ "葦原神社「諏方本社と流鏑馬頭」 下伊那郡大鹿村". 諏訪大社と諏訪神社(附・神社参拝記). 八ヶ岳原人.

- ↑ "塩水の湧泉から採取される大鹿村の山塩の謎". 長野県のおいしい食べ方. JA Nagano Chuoukai.

- ↑ Matsumae, Takashi. 日本神話の形成 (Nihon shinwa no keisei). Hanawa Shobō. p. 431.

- ↑ Satō, Shigenao, ed. (1901). 南信伊那史料 巻之下 (Nanshin Ina Shiryō, vol. 02). p. 55.

- ↑ Miyachi (1931b). pp. 48-49.

- ↑ Pate, Alan Scott (2013). Ningyo: The Art of the Japanese Doll. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 135–136. ISBN 978-1462907205.

- ↑ Spracklen, Karl; Lashua, Brett; Sharpe, Erin; Swain, Spencer, eds. (2017). The Palgrave Handbook of Leisure Theory. 978-1137564795. pp. 173–175.

- ↑ Miyachi (1931b). pp. 45-46.

- ↑ Ihara, Kesao (2008-03-31). "鎌倉期の諏訪神社関係史料にみる神道と仏道 : 中世御記文の時代的特質について (Shinto and Buddhism as Depicted in Historical Materials Related to Suwa Shrines of the Kamakura Period : Temporal Characteristics of Medieval Imperial Writings)". Bulletin of the National Museum of Japanese History. 139: 157–185. (in Japanese)

- ↑ Hall, John Whitney, ed. (1988). The Cambridge History of Japan, Volume 1: Ancient Japan. Cambridge University Press. p. 343. ISBN 978-0521223522.

- ↑ Suwa Daimyōjin Ekotoba, in Hanawa (1919). pp. 521–522.

- ↑ Suwa Kyōikukai (1938). p. 11.(in Japanese)

- ↑ Miyasaka (1987). p. 35.

- ↑ "大祝有員 (Ōhōri Arikazu)". Official website of Suwa City (in Japanese).

- ↑ "諏方氏 (Suwa Clan)". Official website of Suwa City (in Japanese).

- ↑ Ihara (2008). pp. 260-262.

- ↑ Fukushima, Masaki (福島正樹). "信濃古代の通史叙述をめぐって (Shinano kodai no tsūshi jojutsu wo megutte)". 科野太郎の古代・中世史の部屋. Retrieved 2017-09-24.

- ↑ Itō, Rintarō (伊藤麟太朗) (1994). "所謂『阿蘇氏系図』について (Iwayuru 'Aso-shi Keizu' ni tsuite)". Shinano (信濃). Shinano Shigakukai (信濃史学会). 46 (8): 696–697.

- ↑ Murasaki, Machiko (村崎真智子) (1996). "異本阿蘇氏系図試論 (Ihon Aso-shi keizu shiron)". Hito, mono, kotoba no jinruigaku: Kokubu Naoichi Hakushi beiju kinen ronbunshū (ヒト・モノ・コトバの人類学. 国分直一博士米寿記念論文集). Keiyūsha (慶友社): 202–218.

- ↑ Asoshina, Yasuo (阿蘇品 保夫) (1999). 阿蘇社と大宮司―中世の阿蘇 (Aso-sha to Daiguji: chusei no Aso). Ichinomiya-machi (一の宮町). ISBN 978-4877550462.

- ↑ For a contrary viewpoint, cf. Hōga, Yoshio (宝賀寿男) (2006). "村崎真智子氏論考「異本阿蘇氏系図試論」等を読む".

- ↑ "金刺氏 (Kanasashi-shi)". 播磨屋 (harimaya.com). (in Japanese)

- ↑ Miyasaka (1992), pp. 7–11.

- ↑ Miyasaka (1987). pp. 35-36.

- ↑ Kanai, Tenbi (2018). 諏訪信仰の性格とその変遷―諏訪信仰通史 (Suwa shinkō no seikaku to sono hensen: Suwa shinko tsūshi). in Kodai Buzoku Kenkyūkai, ed. pp. 36-38.

- 1 2 Ihon Asoshi Keizu, cited in Kanai (1982). p. 109.

- ↑ Kanai, Tenbi (2018). Suwa shinkō no seikaku to sono hensen: Suwa shinko tsūshi. in Kodai Buzoku Kenkyūkai, ed. pp. 38-41.

- ↑ Ihara (2008). p. 261.

- 1 2 Ōhōri-bon Jinshi Keizu, cited in Kanai (1982). pp. 107, 190.

- 1 2 Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (1995). pp. 811–814.

- ↑ Miyasaka (1987), p. 21.

- 1 2 Miyasaka (1992), pp. 92-93.

- ↑ Miyachi (1931b). pp. 47–48.

- 1 2 3 4 Suwa Nobushige Gejō (諏訪信重解状), in Suwa Kyōikukai, ed. (1931). 諏訪史料叢書 巻15 (Suwa shiryō-sōsho, vol. 15) (in Japanese). Suwa: Suwa Kyōikukai.

- 1 2 Fukuda; Nihonmatsu; Tokuda, eds. (2015). p. 122.

- 1 2 Grumbach (2005). p. 156.

- 1 2 Takei, Masahiro (1999). "祭事を読む-諏訪上社物忌令之事- (Saiji wo yomu: Suwa Kamisha monoimi no rei no koto)". 飯田市美術博物館 研究紀要 (Bulletin of the Iida City Museum). 9: 121–144.

- ↑ "十六大国一覧表" (PDF). 原始仏教聖典資料による釈尊伝の研究 (A Study of the Biography of Sakya-muni Based on the Early Buddhist Scriptural Sources).

- ↑ "佛說仁王般若波羅蜜經 第2卷". CBETA (Chinese Buddhist Electronic Text Association) 漢文大藏經.

- 1 2 Fukuda; Nihonmatsu; Tokuda, eds. (2015). pp. 114-116.

- 1 2 Takei (1999), pp. 129–130.

- 1 2 Miyachi (1931b). p. 84.

- ↑ Translation based on Grumbach (2005). p. 210.

- ↑ Hanawa, Hokiichi, ed. (1914). 諏訪大明神繪詞 (Suwa Daimyōjin Ekotoba). Zoku Gunsho-ruijū (続群書類従). 3. Zoku Gunsho-ruijū Kanseikai. p. 534. (in Japanese)

- ↑ Grumbach (2005). p. 206.

- ↑ 諏方大明神講式 (Suwa Daimyōjin Kōshiki), in Takeuchi, Hideo, ed. (1982). 神道大系 神社編30 諏訪 (Shintō Taikei, Jinja-hen vol. 30: Suwa). Shintō Taikei Hensankai.

- ↑ "諏方大明神講式 (Suwa Daimyōjin Kōshiki)". 国文学研究資料館 (National Institute of Japanese Literature).

- ↑ Fukuda; Nihonmatsu; Tokuda, eds. (2015). p. 116.

- ↑ Fukuda; Nihonmatsu; Tokuda, eds. (2015). p. 115.

- ↑ Suwa Jinja Engi (諏訪神社縁起 上下卷), in Suwa Kyōikukai, ed. (1937). 諏訪史料叢書 巻26 (Suwa Shiryō Soshō, vol. 26). Suwa Kōikukai. pp. 54–64.

- ↑ Miyachi (1931b). p. 85.

- ↑ Text and commentary in Kanai (1982). pp. 162-172.

- ↑ Kanai (1982). p. 167.

- ↑ Fukuda; Nihonmatsu; Tokuda, eds. (2015). pp. 117-118.

- ↑ Kanai (1982). p. 163.

- ↑ Fukuda; Nihonmatsu; Tokuda, eds. (2015). pp. 119-120.

- ↑ Kanai (1982). pp. 168-169.

- ↑ Kanai (1982). p. 169.

- 1 2 3 Text and commentary in Kanai (1982). pp. 173-187.

- ↑ Kanai (1982). pp. 173-174.

- ↑ Fukuda; Nihonmatsu; Tokuda, eds. (2015). pp. 117, 119.

- ↑ Kanai (1982). pp. 176-177.

- ↑ Kanai (1982). p. 175.

- ↑ Miyasaka (1987). pp. 51-54.

- ↑ John Breen; Mark Teeuwen (January 2000). Shinto in History: Ways of the Kami. University of Hawaii Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-8248-2363-4.

- ↑ Carmen Blacker (2 August 2004). The Catalpa Bow: A Study of Shamanistic Practices in Japan. Routledge. ISBN 1-135-31872-7.

- ↑ Kanai (1982). pp. 278–317.

- 1 2 3 4 諏訪縁起の事 (Suwa engi-no-koto) in Kishi, Shōzō (trans.) (1967). Shintōshū (神道集). Tōyō Bunko (東洋文庫) vol. 94. Heibonsha. pp. 238–286. ISBN 978-4-582-80094-4.

- 1 2 3 Kanai (1982). p. 17.

- ↑ Kishi (trans.) (1967). p. 282.

- ↑ Fukuda; Nihonmatsu; Tokuda, eds. (2015). pp. 130-132.

- ↑ Grumbach (2005). pp. 155-156.

- ↑ Imai (1976). p. 37-38.

- ↑ Kobuzoku Kenkyūkai, ed. (2017b). p. 106.

- ↑ Imai (1976). pp. 39-40.

- ↑ Tanigawa, ed. (1987). p. 379.

- ↑ "小野神社ねんじり棒祭". The Hachijuni Culture Foundation. The Hachijuni Culture Foundation.

- ↑ Imai (1976). p. 40.

- ↑ Tanigawa, ed. (1987). p. 381.

- ↑ Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (1995). pp. 681-683.

- ↑ Miyasaka (1992). pp. 88-91.

- ↑ "藤島社・藤島大明神". 諏訪大社と諏訪神社(附・神社参拝記). 八ヶ岳原人.

- ↑ "諏訪大社上社「御田植祭」". 諏訪大社と諏訪神社(附・神社参拝記). 八ヶ岳原人.

- ↑ Hanawa, ed. (1914). p. 530.

- ↑ Kanai (1982). p. 262.

- ↑ Fukuda; Nihonmatsu; Tokuda, eds. (2015). pp. 114-115.

- 1 2 Imai (1960). pp. 3-15.

- 1 2 Imai (1976). p. 41.

- 1 2 Moriya, Sanae (2017). 守矢神長家のお話し (Moriya Jinchōke no ohanashi), in Jinchōkan Moriya Historical Museum (ed.). 神長官守矢史料館のしおり (Jinchōkan Moriya Shiryōkan no shiori) (3rd ed.). Jinchōkan Moriya Historical Museum. pp. 2–3. (in Japanese)

- ↑ "洩矢神社 岡谷市川岸橋原". 諏訪大社と諏訪神社(附・神社参拝記). 八ヶ岳原人.

- ↑ "洩矢神社 (Moriya Shrine)". 長野県神社庁 (Nagano-ken Jinjachō).

- 1 2 3 Kobuzoku Kenkyūkai, ed. (2017b). p 79.

- ↑ "蟹河原 (茅野市ちの横内)". たてしなの時間. 蓼科企画.

- ↑ Shinano-no-kuni Kansha Suwa-jinja Jinchōkan Moriya-ke Ryaku-keizu (信濃國官社諏訪神社神長官守矢家略系圖), in Nobukawa, Kazuhiko (延川和彦); Iida, Kotaro (飯田好太郎) (1921). 諏訪氏系図 続編 (Suwa-shi Keizu, Zokuhen). p. 19.

- ↑ Aston, William George (1896). "

- ↑ "

- ↑

- ↑ Imai (1960). pp. 42-49.

- ↑ Imai (1976). pp. 46-51.

- ↑ Miyasaka (1987). p. 22.

- ↑ "先宮神社". 人力(じんりき)- 旧街道ウォーキング.

- ↑ Kanai (1982). pp. 165.

- ↑ Takei (1999), p. 134.

- ↑ Takei (1999), p. 139.

- ↑ Kanai (1982). pp. 165, 177-179.

- 1 2 3 Takei (1999), p. 136-137.

- ↑ "蛙狩神事 元旦". 諏訪大社と諏訪神社(附・神社参拝記). 八ヶ岳原人.

- ↑ Miyasaka (1992). p. 20

- 1 2 Kanai (1982). pp. 177-178.