Budai

Budai, Hotei or Pu-Tai[1][2] (Chinese: 布袋; pinyin: Bùdài; Japanese: 布袋, translit. Hotei; Vietnamese: Bố Đại) is a semi-historical monk as well as deity who was introduced into the Zen Buddhist pantheon.[3] He allegedly lived around the 10th century in the Wuyue kingdom. His name literally means "Cloth Sack",[3] and refers to the bag that he is conventionally depicted as carrying as he wanders aimlessly. His jolly nature, humorous personality, and eccentric lifestyle distinguishes him from most Buddhist masters or figures. He is almost always shown smiling or laughing, hence his nickname in Chinese, the "Laughing Buddha" (Chinese: 笑佛; pinyin: Xiào Fó).[2] The main textual evidence pointing to Budai resides in a collection of Zen Buddhist monks’ biographies known as the "Ching te chuan teng lu", also known as The Transmission of the Lamp.[4]

Hagiography

Budai has origins centered around cult worship and local legend.[3] He is traditionally depicted as a fat, bald monk wearing a simple robe. He carries his few possessions in a cloth sack, being poor but content.[5] He would excitingly entertain the adoring children that followed him and was known for patting his large belly happily. His figure appears throughout Chinese culture as a representation of both contentment and abundance. Budai attracted the townspeople around him as he was able to predict people’s fortunes and even weather patterns.[4] The wandering monk was often inclined to sleep anywhere he came to, even outside, for his mystical powers could ward off the bitter colds of snow and his body was left unaffected. A recovered death note dated to 916 A.D., which the monk himself wrote, claims that he is an incarnation of the Maitreya, The Buddha of the Future.[4]

Chan/Zen Buddhism

Budai was one of several "uncommitted saints" (C: sansheng) that became incorporated into the Zen Pantheon.[3] Similar "eccentric" figures from the lamp histories were never officially inducted or appropriated into the Chan patriarchal line. Instead, these obscure figures represented the "special transmission" that occurred during the early to mid 12th century. This transmission did not rely on patriarchal lineage for legitimacy, but instead used the peculiar personalities and qualities of various folkloric figures to illustrate the Chan tradition's new commitment to the idea of "awakening" and the propagation of Chan to a larger congregation. The Chan Masters, Dahui Zonggao (1089–1163) and Hongzhi Zhengjue (dates), were both leaders in the initial merging of local legend and Buddhist tradition.[3] They hoped the induction of likeable and odd figures would attract all types of people to the Chan tradition, no matter their gender, social background, or complete understanding of the dharma and patriarchal lineage.[3] Bernard Faure summarizes this merging of local legend and Chan tradition by explaining, "One strategy in Chan for domesticating the occult was to transform thaumaturges into tricksters by playing down their occult powers and stressing their thus world aspect..."[3] The movement allocated the figures as religious props and channeled their extraordinary charismas into the lens of the Chan pantheon in order to appeal to a larger population. Ultimately, Budai was revered from both a folkloric standpoint as a strange, wandering vagabond of the people as well as from his newfound personage within the context of the Chan tradition as a 'mendicant priest'[3] who brought abundance, fortune, and joy to all he encountered with the help of his mystical "cloth sack" bag.

Visual representations of Budai

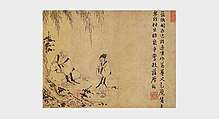

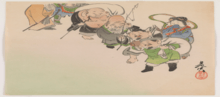

As Zen Buddhism was transmitted to Japan around the 13th century, the devout monastics and laymen of the area utilized figure painting to portray the characters central to this "awakening" period of Zen art.[3] Many of the eccentric personalities that were inducted into the Zen tradition like Budai were previously wrapped up in the established culture and folklore of the Japanese people. The assimilation and reapplication of these wondrous charismas to the Zen pantheon assisted in the expansion of the Zen tradition. Budai is almost always depicted with his "cloth sack" that looks like a large bag. The bag serves as a prominent motif within the context of Zen Buddhism as it represents abundance, prosperity, and contentment. Ink paintings such as these attributed to Budai often had an inscription and seal that signaled to high ranking officials. For example, Budai and Jiang Mohe was inscribed by Chusi Fanqi, who was closely related to Song Lian (1310–1381) and Wei Su (1295–1372).

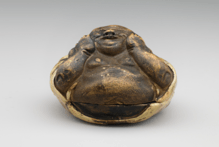

As the images demonstrate, Budai is most jubilant when in the presence of others, especially children. When depicted with other gods in "the Seven Lucky Gods", Budai maintains a solemn or even depressed countenance. Budai's round figure comes into practical use through the sculpting of the incense box (18th century) that splits the monk's body into two halves. The newer images such as Hotei and Children Carrying Lanterns (19th century) employs much more color, dramatization of physical features, and detail than the older pieces such as Hotei from Mokuan Rein (1336) that employs much more wispy and heavily contrasting outlines of his figure with no color or assumed setting.

Conflation with other religious figures

Angida Arhat

Angida was one of the original Eighteen Arhats. According to legend, Angida was a talented Indian snake catcher whose aim was to catch venomous snakes to prevent them from biting passers-by. Angida would also remove the snake's venomous fangs and release them. Due to his kindness, he was able to attain bodhi.

In Chinese art, Angida is sometimes portrayed as Budai, being rotund, laughing, and carrying a bag.[6]

Phra Sangkajai/Phra Sangkachai

In Thailand, Budai is sometimes confused with another similar monk widely respected in Thailand, Phra Sangkajai or Sangkachai (Thai: พระสังกัจจายน์). Phra Sangkajai (Thai: มหากัจจายนเถระ), a Thai rendering of Kaccayana, was an arhat during the time of the Buddha. Buddha praised Phra Sangkachai for his excellence in explaining sophisticated dharma (or dhamma) in an easily and correctly understandable manner. Phra Sangkajai (Maha Kaccana) also composed the Madhupinadika Sutra (Madhupindika Sutta MN 18).

One tale of the Thai folklore relates that he was so handsome that once even a man wanted him for a wife. To avoid a similar situation, Phra Sangkadchai decided to transform himself into a fat monk. Another tale says he was so attractive that angels and men often compared him with the Buddha. He considered this inappropriate, so disguised himself in an unpleasantly fat body.

Although both Budai and Phra Sangkachai may be found in both Thai and Chinese temples, Phra Sangkachai is found more often in Thai temples, and Budai in Chinese temples. Two points to distinguish them from one another are:

- Phra Sangkajai has a trace of hair on his head (looking similar to the Buddha's) while Budai is clearly bald.

- Phra Sangkajai wears the robes in Theravada fashion, with the robes folded across one shoulder, leaving the other uncovered. Budai wears the robes in Chinese style, covering both arms but leaving the front part of the upper body uncovered.

References

- ↑ Cook, Francis Dojun. How to Raise an Ox. Wisdom Publications. p. 166 note 76. ISBN 9780861713172.

- 1 2 "The Laughing Buddha". Religionfacts.com. Retrieved 2011-12-26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Levine, Gregory (2007). Awakenings: Zen Figure Painting in Medieval Japan. Japan Society.

- 1 2 3 Chapin, H. B. (1993). The Chan Master Pu-tai. Journal of the American Oriental Society.

- ↑ Seow (2002). Legend of the Laughing Buddha. Asiapac Books.

- ↑ Seo, Audrey Yoshiko; Addiss, Stephen (2010). The Sound of One Hand: Paintings and Calligraphy by Zen Master Hakuin. Shambhala Publications. p. 205. ISBN 9781590305782.

External links

- Who Is the Laughing Buddha? Zen's Artistic Heritage