Suwa-taisha

| Suwa Grand Shrine 諏訪大社 (Suwa taisha) | |

|---|---|

| |

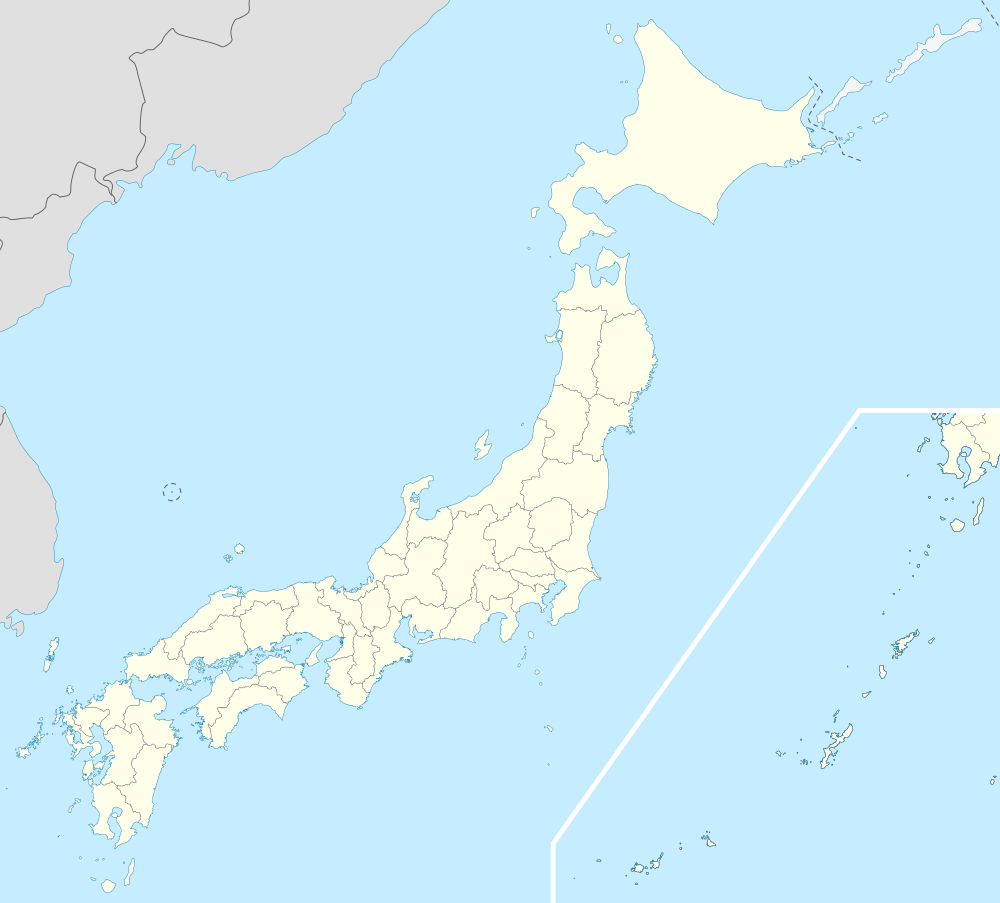

Shown within Japan | |

| Basic information | |

| Location |

Chino City, Nagano (Kamisha Maemiya) Suwa City, Nagano (Kamisha Honmiya) Shimosuwa, Nagano (Shimosha) |

| Geographic coordinates |

35°59′53″N 138°07′10″E / 35.99806°N 138.11944°E (Kamisha Honmiya) |

| Affiliation | Shinto |

| Deity | Takeminakata (Suwa Myōjin), Yasakatome |

| Website |

suwataisha |

| Date established | circa 6th century? |

|

| |

Suwa Grand Shrine (Japanese: 諏訪大社 Hepburn: Suwa taisha), historically also known as Suwa Shrine (諏訪神社 Suwa Jinja) or Suwa Daimyōjin (諏訪大明神), is a group of Shinto shrines in Nagano Prefecture, Japan. The shrine complex is considered to be one of the oldest shrines in existence, being implied by the Nihon Shoki to already stand in the late 7th century.[1]

Overview

The entire Suwa shrine complex consists of four main shrines grouped into two sites: the Upper Shrine or Kamisha (上社), comprising the Maemiya (前宮, former shrine) and the Honmiya (本宮, main shrine), and the Lower Shrine or Shimosha (下社), comprising the Harumiya (春宮, spring shrine) and the Akimiya (秋宮, autumn shrine).[2][3] The Upper Shrine is located on the south side of Lake Suwa, in the cities of Chino and Suwa, while the Lower Shrine is on the northern side of the lake, in the town of Shimosuwa.[4][5]

In addition to these four main shrines, some sixty other auxiliary shrines scattered throughout the Lake Suwa area (ranging from miniature stone structures to medium to large sized edifices and compounds) are also part of the shrine complex. These are the focus of certain rituals in the shrine's religious calendar.[6]

Historically, the Upper and the Lower Shrines have been two separate entities, each with its own set of shrines and religious ceremonies. The existence of two main sites, each one having a system parallel to but completely different from the other, complicates a study of the Suwa belief system as a whole. One circumstance that simplifies the matter somewhat, however, is that very little documentation for the Lower Shrine has been preserved; almost all extant historical and ritual documents regarding Suwa Shrine extant today are those of the Upper Shrine.[7]

Deities

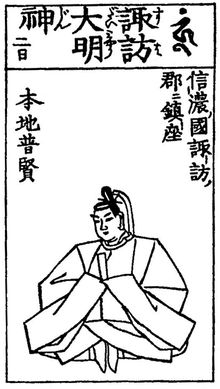

The god of the Upper Shrine, named Takeminakata (also 'Minakatatomi' or 'Takeminakatatomi') in the imperially-commissioned official histories, is also often popularly referred to as Suwa (Dai)myōjin. The goddess of the Lower Shrine, held to be this god's consort, is given the name Yasakatome in these records.

Although these are the official identities of the shrine's gods, most of its rituals are actually not so much concerned with their identities but with their character as Mishaguji, local agricultural and fertility deities.[9] The name 'Takeminakata' in fact does not appear in historical records of the Upper Shrine's religious rites; rather, the focus of worship in these rituals are often identified as the Mishaguji.[10][11][12]

While both the Kojiki (720 CE) and the Sendai Kuji Hongi (807-936 CE) portray Takeminakata as a son of Ōkuninushi, the god of Izumo Province, who was driven into exile in Suwa after his shameful defeat in the hands of a messenger sent by the gods of heaven,[13][14][15][16] other myths portray the Suwa deity differently: in one story, for instance, the god is an immigrant who conquered the region by defeating various local deities who resisted him.[17][18][19][20][21] In a medieval Buddhist legend, Suwa Myōjin was a king from India whose feats included quelling a rebellion in his kingdom and defeating a dragon in Persia before manifesting in Japan as a native kami.[22][23] In another medieval folk story, the god was a warrior named Kōga Saburō who returned from a journey into the underworld only to find himself transformed into a serpent or dragon.[15][24][25][26] A fourth myth portrays the Suwa deity as an entity without a physical form who then chose an eight-year old boy to become his priest and physical 'body'.[27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34]

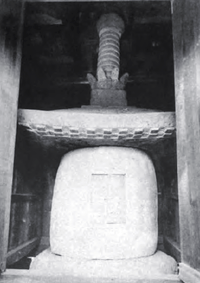

Like others among Japan's oldest shrines, three of Suwa Shrine's four main sites - the Kamisha Honmiya and the two main shrines of the Shimosha - do not have a honden, the building that normally enshrines a shrine's kami.[35] Instead, the Upper Shrine's objects of worship were the sacred mountain behind the Kamisha Honmiya,[36][37][38][35] a sacred rock (磐座 iwakura) upon which Suwa Myōjin was thought to descend,[39][38] and the shrine's former high priest or Ōhōri, who was considered to be the physical incarnation of the god himself.[40] This was later joined by Buddhist structures (removed or demolished during the Meiji period) which were also revered as symbols of the deity.[41]

The Lower Shrine, meanwhile, has sacred trees for its go-shintai: a sugi tree in the Harumiya, and a yew tree in the Akimiya.[35][38][42][43]

History

Early history

Upper Shrine

The Suwa region during the late Yayoi period was thought to have been originally populated by autonomous village communities, which were eventually united under a single priest-chieftain who governed the local religious practices centered around the worship of nature spirits known as the Mishaguji, gods of fertility and agriculture who were also considered to be guardians of local communities.[44][45][46][47] These communities were eventually subsumed into the expanding Yamato state around the 6th to 7th centuries; the appearance of burial mounds markedly different from the type heretofore common in the region are taken to be signs of the Lake Suwa area coming under Yamato rule.[48][49][50]

Local historians have seen the myths that speak of Suwa Myōjin's conquest of the area to reflect power struggles and changing alliances in the 7th and 8th centuries, after the establishment of the ritsuryō government.[51] The god of Suwa's mythic victory over the god Moreya, for instance, is considered to reflect the historical usurpation of control over the regional deity by an immigrant clan known as the Kanesashi (金刺, also read as 'Kanasashi'), which as district magistrates (郡領 gunryō) were in charge of producing and collecting taxed goods and laborers to be sent to the central government in Yamato Province.[52] The Kanesashi's seat of power seems to have been located north of Lake Suwa, near what is now the Lower Shrine, although there was not yet a shrine there at the time. This location was closer to the important crossroads that led to the capital.[53]

According to a genealogical list of the Aso clan (purportedly related to the Kanesashi) of Aso Shrine in Kyushu, the Aso-ke Ryaku Keizu (阿蘇家略系図), a man named Otoei (乙頴) or Kumako (神子 or 熊古), son of the Kanesashi clan leader and kuni no miyatsuko Mase-gimi (麻背君) - identified here as the legendary high priest (Ōhōri) chosen by the Suwa deity to become his 'body' - founded "a shrine ... at the foot of the mountain" to the god in "the second year of Iware Ikenobe no Ōmiya" (587 CE), what would eventually be known as the Upper Shrine.[55][56][50] While the historical reliability of this genealogy has been called into question,[57][58][59][60][61] it nevertheless shows the importance of the Kanesashi in garnering official recognition for what had once been a local cult and the founding of the shrines.[62]

The office of Ōhōri, a boy priest-shaman revered as deity incarnate, might have been originally instituted as a way to absorb native religious practices into the Yamato belief system.[50] The local line of priest-chiefs whose religious authority was usurped by the Kanesashi, what would later become known as the Moriya (守矢) clan, was integrated into the new system as the Jinchōkan, the priest who had the prerogative to summon the Mishaguji in rituals. The Moriya's submission to and cooperation with the new system enabled the local Mishaguji cult to survive underneath it: while officially subservient to the Ōhōri, in reality the Jinchōkan, who presided over all the shrine ceremonies, continued to wield authority while the Ōhōri was but a symbolic presence.[63] In fact, the Ōhōri, the new god to be worshipped, can only become a living deity by being made to be possessed by the Mishaguji by the Jinchōkan, the representative of those who worship the old god.[64][65]

.png)

The Nihon Shoki (720 CE) refers to envoys sent to worship "the wind-gods of Tatsuta and the gods of Suwa and Minochi in Shinano"[lower-alpha 1] during the fifth year of the reign of Empress Jitō (691 CE).[1] This record testifies to the worship of the Suwa deity (embodied by the Ōhōri) as a water and/or wind deity during the late 7th century, on par with the wind gods of Tatsuta in Yamato Province (modern Nara Prefecture).[66][67]

'Takeminakata', the name by which Suwa Myōjin is more commonly known to the imperial court, appears in the historical record for the first time in the Kojiki's (711-712 CE) kuni-yuzuri myth cycle.[68] Although the work portrays Takeminakata as a god hailing from Izumo Province, references to such a deity are curiously absent from the Nihon Shoki or other sources dealing with the province. Due to this silence, it is thought that the god might have been interpolated by the Kojiki's chief compiler, Ō no Yasumaro, into a story which did not originally feature him.[69][70][71][68] Scholars believe various factors were at play for Takeminakata's introduction in the Kojiki's narrative - one being that Yasumaro's clan, the Ō, were distantly related to the Kanesashi.[72][73] Takeminakata's inclusion in the Kojiki might have thus been a means to promote the Kanesashi's local cult and ensure its rise in prominence.[74][75]

As the Kanesashi, a clan of provincial (and thus 'inferior') origins, rose in rank, so too did their deities rise up in rank.[76] The national histories record Takeminakata's exceptionally rapid rise in importance: from rankless (无位), the imperial court steadily promoted the deity to increasingly higher ranks within the space of twenty-five years, beginning with junior fifth, upper grade (従五位上) in 842 CE.[77]) By 867 CE, 'Takeminakatatomi-no-Mikoto' is recorded in the Nihon Sandai Jitsuroku as being elevated to the rank of junior first (従一位).[78][77]

Lower Shrine

The Aso clan genealogy relates that Otoei's brother, Kuratari (倉足), was the district magistrate (評督 hyōtoku or koori no kami) of Suwa. His immediate descendants, who bore the Kanesashi name, are in turn also recorded as administrative heads (gunryō) of Suwa district.[79]

_seal_imprint.png)

The Nihon Sandai Jitsuroku mentions a Kanesashi, Sadanaga (貞長), receiving the kabane Ōason (大朝臣) in the year 863.[lower-alpha 2][80] A genealogy of the Lower Shrine's high priestly line records an elder brother of his, Masanaga (正長), who in addition to being the district governor (大領 dairyō) of Hanishina District, also held the title of Megamihōri (売神祝) or 'priest of the goddess'. The same title appears in a seal in the Lower Shrine's possession (designed as an Important Cultural Property in 1934) traditionally said to have been bequeathed by the Emperor Heizei (reigned 806-809).[81][82]

References to other members of the Kanesashi rising to positions of prominence during the 8th to 9th centuries are found in the official histories. A Kanesashi from Ina District, Hachimaro (八麻呂), was given the rank of outer junior fifth, lower grade (外従五位下) by the court for quelling rebellion after the death of Fujiwara no Nakamaro in 764 CE - the 'outer' indicating his origins from a provincial clan. A female clan member from Minochi (encompassing the modern districts of Kamiminochi and Shimominochi and part of Nagano, Iiyama, and Nakano), Kanesashi no Wakashima (金刺若嶋), was granted the same title in 770 CE, with 'outer' being removed from her title in 777 CE upon the clan's gaining status as an aristocracy.[83][84]

Scholars believe that the Lower Shrine and its goddess - named 'Yasakatome' in imperial histories - was created by the Kanesashi as a way to receive higher appointments in rank from the court, in competition with the Moriya family who were the Upper Shrine's priests.[85] The Lower Shrine may have started as a kind of ancestral shrine to the clan's forebears, with its female god meant to deliberately contrast with the Upper Shrine's male deity.[86]

As Takeminakata, the Upper Shrine's god, rose up in rank, so did Yasakatome,[87] so that by 867 CE, the goddess had been promoted to senior second rank (正二位).[78]

Heian and Kamakura periods

While two genealogical lists of disputed historical value, of which the aforementioned Aso clan genealogy is one, identify Otoei/Kumako as the first priest of Suwa Myōjin, traditionally this priest is instead believed to be Arikazu (有員),[27] who is thought to have lived during the early 9th century, somewhere during the reigns of emperors Kanmu (781-806), Heizei (806-809) or Saga (809-823).[88] Some sources in fact go so far as to claim (without historical basis) that Arikazu was a son of Kanmu and an imperial prince.[88][89][90][91] Nevertheless, a possible connection between Arikazu and the imperial court does exist that might have engendered this belief: a medieval legend relates that the Suwa deity appeared to the 8th century general Sakanoue no Tamuramaro during his campaign to subjugate the Emishi of northeastern Japan; in thanksgiving for the god's assistance, Tamuramaro was said to have petitioned the court for the institution of the shrine's religious festivals.[92][93] Scholars have thought that this story might be ultimately based on Arikazu (who, as Ōhōri, was the deity himself in bodily form) ingratiating himself with the imperial court, perhaps to make up for his shrine having had little contact with the central government compared with the Kanesashi family in the north.[94] Thanks to his connections with Tamuramaro and the court, Arikazu exerted great influence such that later tradition came to identify him with the mythical first Ōhōri and progenitor of the Upper Shrine's high priestly line.[95]

By the late Heian period, Suwa became considered as Shinano's chief shrine or ichinomiya.[96][97] with literary mentions attesting to its status. The 'Register of Deities' (神名帳 Jinmyōchō) section of the Engishiki (927 CE) lists the 'Minakatatomi Shrines' (南方刀美神社) as the two major ('eminent') shrines of Suwa district.[lower-alpha 3][98] 'Suwa Shrine of Shinano' is mentioned briefly in Minamoto no Tsuneyori (976/985-1039) diary, the Sakeiki (左経記) as the representative shrine for Shinano Province when Emperor Go-Ichijō sent an envoy to shrines in every province in the country in 1017 CE.[99][100] The Ryōjin Hishō, an anthology of songs compiled in 1179, names the shrine of Suwa among famous shrines to martial deities in the eastern half of the country.[101]

As Buddhism began to penetrate Suwa and syncretize with local beliefs, the deities of the Upper and Lower Shrines came to be identified with the bodhisattvas Samantabhadra (Fugen) and Avalokiteśvara (Kannon), respectively.[102][103][41] Buddhist temples and other edifices (most of which belonged to the esoteric Shingon school) were erected on the precincts of both shrines, such as a sanctuary to Samantabhadra known as the Fugendō (普賢堂) and a stone pagoda symbolizing the legendary iron tower in India where, according to Shingon tradition, Nagarjuna was said to have received esoteric teachings from Vajrasattva (considered to be an aspect of Samantabhadra) called the Tettō (鉄塔 "iron tower"). For a long time, these two structures were considered as the Upper Shrine's objects of worship.[41] As Buddhist ethics, which opposed the taking of life and Mahayana's strict views on vegetarianism somewhat conflicted with Suwa Myōjin's status as a god of hunting, the Suwa cult devised elaborate theories that legitimized the hunting, eating, and sacrifice of animals such as deer (a beast sacred to the god) within a Buddhist framework.[104] The shrines produced special talismans (鹿食免 kajikimen "permit to eat venison") and chopsticks (鹿食箸 kajikibashi) that were held to allow the bearer to eat meat.[35][105]

A significant change in the Suwa cult in the medieval period was its association with samurai culture. The prominence of hunting in the shrine's religious rites undoubtedly caught the attention of warriors.[106] Devotion to Suwa Myōjin (especially as god of war) became more widespread thanks in part to the rise of the Upper Shrine's high priestly family - now calling themselves the Jin/Miwa (神) or the Suwa (諏訪)[107] - as vassals (gokenin) of the Kamakura shogunate and the Hōjō clan.[108] The shrines of Suwa and the priestly clans thereof flourished under the patronage of the Hōjō, which promoted devotion to the god as a sign of loyalty to the shogunate. The religious festivals of the Upper and Lower Shrines attracted many of the samurai caste as well as other social classes, both from within Shinano and outside.[108] The Hōjō appointed local land managers (jitō) and retainers, who were sometimes Hōjō family members, as sponsors (御頭 otō or ontō) of the festivals, which helped provide financial support for the shrines.[109] To offset the burden of this service, these sponsors enjoyed a number of benefits such as exemption from certain provincial taxes and the right to be pardoned for crimes during their year of service as otō.[110]

.png)

Around this time, Suwa branch shrines became numerous all across Japan, especially in territories held by clans devoted to the god (for instance, the Kantō region, traditional stronghold of the Minamoto (Seiwa Genji) clan).[111] A number of factors were instrumental for this spread of the Suwa Myōjin cult. First, warriors from Shinano Province who were rewarded lands in the western provinces by the shogunate in the aftermath of the Jōkyū War of 1221 took the Suwa cult with them. Second, the shogunate appointed major non-Shinano vassals to manors in the province, who then acted as sponsors and participants in the shrine rituals, eventually installing the cult in their native areas.[112] A third factor was the exemption granted to the shrines of Suwa from the ban on falconry (takagari) - a favorite sport of the upper classes - imposed by the shogunate in 1212, due to the importance of hunting in its rites. As a loophole to this ban, the gokenin built Suwa branch shrines in their own provinces where 'Suwa style' falconry could be performed, ostensibly to collect offerings for the shrine.[113]

The Suwa cult was also propagated by wandering preachers (御師 oshi) who traveled around Shinano and neighboring provinces, preaching stories about the Suwa deity as well as distributing kajikimen and kajikibashi to the populace, collecting offerings and donations in exchange. The Suwa oshi also carried with them miniature replicas of the iron bells (鉄鐸 tettaku) which were used to call forth the Mishaguji in some rituals as well as seal promises and agreements in the god's name.[105][114][115]

In 1249, the Upper Shrine's Ōhōri, Suwa Nobushige (諏訪信重), sent an appeal (解状 gejō) to the shogunate after becoming embroiled in a dispute with Kanesashi Morimoto (金刺盛基), the high priest of the Lower Shrine, as to which of their shrines was the real main shrine of Suwa and thus, is to set a precedent in religious rites. In the petition, Nobushige argued for the antiquity and supremacy of the Upper Shrine contra the Lower Shrine's charges by recounting its origin myths and its ceremonies. Nobushige's appeal is thus an invaluable document for understanding Suwa Shrine's customs and traditions during the early Kamakura period.[116][117]

Muromachi and Sengoku periods

The shrines suffered a heavy setback at the downfall of the Hōjō and the collapse of the shogunate in 1333. Testifying to the close connections between the warrior families of the Suwa region and the Hōjō is the fact that many members of the Suwa clan present in Kamakura during the siege of the city in 1333 committed suicide alongside Hōjō Takatoki.[118]

Takatoki's son, the young Tokiyuki, sought refuge in Shinano with Suwa Yorishige (諏訪頼重, not to be confused with the Sengoku period daimyō of the same name) and his son and then-Ōhōri, Tokitsugu (時継).[119] In July–August 1335, the Suwa and other clans who remained loyal to the Hōjō, led by Tokiyuki, instigated an unsuccessful armed rebellion with the intention of reestablishing the Kamakura shogunate, which ended with the defeat of Tokiyuki's forces and Yorishige, Tokitsugu and some others committing suicide.[119][120][121] Tokitsugu's son who inherited the priesthood, Yoritsugu (頼継), was stripped from his position and replaced by Fujisawa Masayori (藤沢政頼), who hailed from a cadet branch of the clan. Now declared an enemy of the imperial throne, Yoritsugu went into hiding.[119][122]

.jpg)

It is believed that the story of Kōga Saburō, which portrays Suwa Myōjin as a warrior hero and a hunter, originated in the aftermath of the shogunate's collapse and the Suwa Ōhōri's status becoming diminished as a result. Whereas formerly, the Suwa clan relied on the doctrine of the Upper Shrine's high priest being a god in the flesh to exert authority over its warrior devotees (Minamoto no Yoritomo in 1186 chastised subordinates for not obeying the Ōhōri, declaring that his words are those of the god of Suwa himself[123]), with the loss of official backing the Suwa shrine network became decentralized. Warriors who were devoted to the Suwa cult sought for stories (setsuwa) about the deity that did not involve the Ōhōri or the Suwa clan, leading to the rise of localized setsuwa such as the Kōga Saburō legend.[124]

Suwa (or Kosaka) Enchū, government official and member of a cadet branch of the Suwa, took it upon himself to revive the former status of Suwa Shrine.[125] To this end, he commissioned a set of ten illustrated scrolls (later expanded to twelve) showcasing the shrine's history and its various religious ceremonies, which was completed in 1356. The actual scrolls were later lost, but its text portions were copied and widely circulated, becoming known as the Suwa Daimyōjin Ekotoba.[126]

By the 14th century, the high priestly houses of the Upper and Lower Shrines, the Suwa and the Kanesashi were at war with each other and, in the Suwa's case, among themselves. During the Nanboku-chō period, the Suwa supported the Southern Court, while the Kanesashi chose to side with the Northern Court. This and other reasons contributed to the state of war between the two families, as well as other clans allied with them, during the Muromachi and Sengoku periods. During a battle between the two factions in 1483, the Lower Shrines were burned down by the Upper Shrine's forces; its high priest, Kanesashi Okiharu (金刺興春), was killed in battle.[127]

In 1535, Takeda Nobutora of Kai Province, who fought against the Suwa clan a number of times, had a truce with clan leader Suwa Yorishige and sent his daughter Nene off to him as his wife. His clan, the Takeda, were already known to be devotees of the Suwa deity since the 12th century, when in 1140, Takeda Nobuyoshi donated lands to each of the two shrines of Suwa in thanksgiving for his defeat of the Taira. By marrying his daughter to Yorishige, Nobutora was trying to bring himself closer to the Suwa and thus, ensuring that he would receive the blessings of the god.[128]

In 1542, Nobutora's son Shingen invaded Shinano and defeated Yorishige in a series of sieges; two years later Yorishige was forced to commit seppuku.[129][130] Shingen then took Yorishige's daughter (his niece) to be one of his wives and had a son with her, Katsuyori, who would eventually prove to be the downfall of the Takeda.[130] Shingen notably did not give his son the character traditionally used in Takeda names, 信 (nobu), but instead the character 頼 (yori) used for the names of Suwa clan members,[130] apparently as a sign of Katsuyori being the intended heir to the Suwa legacy and of Shingen's desire to place the land of Suwa and its shrines under Takeda control.[131]

After Yorishige's downfall, Suwa was divided between the Takeda and their ally, Takatō Yoritsugu (高遠頼継), who coveted the position of Ōhōri.[132] When he did not receive the priestly office, Yoritsugu invaded the other half of the territory that was in Takeda hands. Ensuring that Yoritsugu will not receive support from the former Suwa retainers, Shingen made Yorishige's son the nominal leader of the forces of resistance and retaliated by capturing Yoritsugu's castles.[133] Shingen is said to have prayed at the Upper Shrine for victory, vowing to donate a horse and a set of armor should he defeat Yoritsugu.[134] His making Yorishige's son the nominal head of his troops is also believed to be a way to invoke the aid of the Suwa deity.[134] Apart from this, there are other recorded instances of Shingen praying to the god to assist him in his campaigns.[135]

From 1565 onwards, Shingen (who by now had conquered the whole of Shinano Province) issued orders for the revival of religious rituals in the Upper and Lower Shrines which were discontinued due to the chaos of war and lack of financial support, which also helped him both strengthen his control over Shinano and unify the people of the province.[136][137][138]

Shingen's devotion to Suwa Myōjin is also evident in some of his war banners, which bore the god's syncretized Buddhist name: Suwa Nangū Hosshō Kamishimo Daimyōjin (諏方南宮法性上下大明神 'Dharma-Nature Daimyōjin of the Suwa Upper and Lower Southern Shrines'), as well as his iconic helmet, the Suwa Hosshō helmet (諏訪法性兜).[139][140]

In 1582, the eldest son of Oda Nobunaga, Nobutada, led an army into Takeda-controlled Shinano and burned the Upper Shrine to the ground.[141][142][143] The shrine was subsequently rebuilt two years later.[144]

Edo and later periods

.jpg)

During the Edo period, both shrines were recognized and supported by the Tokugawa shogunate and the local government, with both being given land grants by the shogun and the local daimyō.[136][137]

The period saw escalating tensions between the priests and the shrine monks (shasō) of the Suwa complex, with increasing attempts from the priesthood to distance themselves from the Buddhist temples. By the end of the Edo period, the priests, deeply influenced by Hirata Atsutane's nativist, anti-Buddhist teachings, became extremely antagonistic towards the shrine temples and their monks. In 1864 and 1867, Buddhist structures in the Lower Shrine were set on fire by unknown perpetrators; in the latter case, it was rumored to have been caused by the shrine's priests.[145]

The establishment of State Shinto after the Meiji Restoration in 1868 brought an end to the union between Shinto and Buddhism. The shrines of Suwa, due to their prominent status as ichinomiya of Shinano, were chosen as one of the primary targets for the edict of separation, which took effect swiftly and thoroughly. The shrine monks were laicized and Buddhist symbols either removed from the complex or destroyed; the shrines' Buddhist rites, such as the yearly offering of the Lotus Sutra to Suwa Myōjin (involving the placing of a copy of the sutra inside the Tettō), were discontinued. The now laicized monks at first tried to continue serving at the shrines as Shinto priests; however, due to continued discrimination from the shrine priesthood, they gave up and left.[146] The priests themselves were soon ousted from their offices as the state abolished hereditary succession among Shinto priests and private ownership of shrines across the country; the Ōhōri - now stripped of his divine status - as well as the other local priestly houses were replaced by government-appointed priests.[147]

In 1871, the Upper and Lower Shrines - now under government control - were merged into a single institution, Suwa Shrine (諏訪神社 Suwa Jinja), and received the rank of kokuhei-chūsha (国幣中社), before being promoted to kanpei-chūsha (官幣中社) in 1896 and finally, to the highest rank of kanpei-taisha (官幣大社) in 1916. After World War II, the shrine was listed as a special-class shrine (別表神社 beppyō-jinja) by the Association of Shinto Shrines and renamed Suwa Grand Shrine (Suwa Taisha) in 1948.

Shrines

Upper Shrine

Kamisha Honmiya

.jpg)

Kamisha Maemiya

The Maemiya (前宮 'former shrine'), as its name implies, is thought to be the oldest site in the Upper Shrine complex and the center of its religious rites.[148] Originally one of the chief auxiliary shrines of the Upper Shrine complex (see below), the Maemiya was elevated to its current status as one of its two main shrines in 1896 (Meiji 29).[149]

While Yasakatome, Suwa Myōjin's consort, is often currently identified as this shrine's deity (with popular legend claiming that the burial mounds of Takeminakata and Yasakatome are to be found in this shrine), medieval records instead associate the Maemiya with the local fertility and agriculture god(s) known as Mishaguji, who occupy a prominent role in the religious rituals held here.[150] The Maemiya is thus more likely to have been originally a place where the 'former' kami of the region, the Mishaguji, were worshipped.[151]

).jpg)

During the Middle Ages, the area around the Maemiya was known as the Gōbara (神原), the 'Field of the Deity', as it was the residence of the Upper Shrine's high priest, the Ōhōri, considered to be the god of Suwa incarnate, and was the site of many important rituals.[152] The Ōhōri's original residence in the Gōbara, the Gōdono (神殿), also functioned as the political center of the region, with a small town (monzen-machi) developing around it.[153] The Gōdono was eventually abandoned after the area was deemed to have become ritually polluted in the aftermath of the intraclan conflict among the Suwa clan[154] which resulted in the death of Ōhōri Suwa Yorimitsu (諏訪頼満) in 1483. In 1601, the Ōhōri's place of residence was moved from the Maemiya to Miyatado (宮田渡) in modern Suwa City.[155]

With the Ōhōri having moved elsewhere, the Gōbara fell into decline during the Edo period as locals began to build houses in the precincts and convert much of it into rice fields; even the shrine priests who still lived nearby used the land for rice farming to support themselves.[156]

Sites and structures

- Honden

- The shrine's current honden was originally built in 1932 with materials formerly used in the Grand Shrine of Ise,[8] replacing a wooden shed that formerly stood on the exact same spot known as the 'purification hut' (精進屋 shōjin-ya).[157][158] This hut was built atop a large sacred rock known as the Gorei'i-iwa (御霊位磐), upon which the Ōhōri engaged in a thirty-day period of strict austerities in preparation for becoming a vessel of the deity.[157][159][160] After being dismantled, the shōjin-ya was eventually rebuilt in what is now a district of modern Chino City and repurposed as a local shrine.[161][162] Immediately by the honden and the rock below it is the supposed burial mound of Takeminakata and/or Yasakatome.[163]

- Beside the honden is a brook known as the Suiga (水眼の清流 Suiga no seiryū),[164] the waters of which were formerly used for ritual ablutions by the Ōhōri.[159]

- Tokoromatsu Shrine (所政社)

- Kashiwade Shrine (柏手社)

- Keikan Shrine (鶏冠社)

- Mimuro Shrine (御室社)

- Wakamiko Shrine (若御子社)

- Uchi-no-mitama-den (内御玉殿)

- Mizogami Shrine (溝上社)

- Jikken-rō (十間廊)

- Formerly also known as the Gōbara-rō (神原廊), the Jikken-rō is a freestanding ten-bay corridor that served as the center of the Upper Shrine's religious ceremonies.[165] Even today, the Ontōsai Festival held in April is performed inside this hallway.

.jpg)

.jpg)

- Mine no tatae (峰の湛)

- Located some couple of hundred metres northwest of the honden[166] by an old road leading to Kamakura,[167][168] this inuzakura (Prunus buergeriana)[169] tree was considered to be one of the tatae (湛, also tatai), natural objects and sites sacred to the Mishaguji. In a spring rite practiced during the medieval period (the precursor of the modern Ontōsai Festival), six boys chosen to be the Ōhōri's symbolic representatives known as the Okō (神使, also Kō-dono or Okō-sama) were divided into three groups of two and dispatched to visit the tatae scattered throughout the whole region and perform rituals therein to the local Mishaguji.[170][171]

.jpg)

Auxiliary shrines

The Upper Shrine is traditionally reckoned to have thirty-nine auxiliary shrines dedicated to local deities, divided into three groups of thirteen shrines (十三所 jūsansho) each.

Kami-Jusanshō (上十三所)

- Tokomatsu / Tokoromatsu Shrine (所政社)

- Maemiya

- Isonami Shrine (磯並社)

- Ōtoshi Shrine (大年社)

- Aratama Shrine (荒玉社)

- Chinogawa Shrine (千野川社)

- Wakamiko Shrine (若御子社)

- Kashiwade Shrine (柏手社)

- Kuzui Shrine (葛井社)

- Mizogami Shrine (溝上社)

- Se Shrine (瀬社)

- Tamao Shrine (玉尾社)

- Homata Shrine (穂股社)

Naka-Jūsansho (中十三所)

- Fujishima Shrine (藤島社) - Suwa City

- According to legend, this shrine marks the spot where Suwa Myōjin planted the weapon he used to defeat the god Moreya (a wisteria vine), which then turned into a forest.[172] The Upper Shrine's rice planting ceremony (御田植神事 Otaue-shinji) is held here every June; the rice planted during this ritual was believed to miraculously ripen after just a single month.[173] A similar ritual exists in the Lower Shrine.[174]

- Another Fujishima Shrine stands in Okaya City by the Tenryū River, which in current popular belief was the two gods' place of battle.

- Uchi-no-mitama-den (内御玉殿) - Maemiya

- A shrine that once housed sacred treasures supposedly brought by the Suwa deity when he first came into the region, which includes a bell (八栄鈴 Yasaka no suzu) and a mirror (真澄鏡 Masumi no kagami).

- Keikan Shrine (鶏冠社) - Maemiya

- A small hokora marking the place where the Ōhōri's investiture ceremony was once held.

- Sukura Shrine (酢蔵神社) - Chino City

- Noyake / Narayaki Shrine (野焼(習焼)神社) - Suwa City

- Gozaishi Shrine (御座石社) - Chino City

- Mikashikidono (御炊殿) - Honmiya

- Aimoto Shrine (相本社) - Suwa City

- Wakamiya Shrine (若宮社) - Suwa City

- Ōyotsu-miio (大四御庵) - Misayama, Fujimi

- Yama-miio (山御庵) - Misayama, Fujimi

- Misakuda Shrine (御作田神社) - unknown

- Akio Shrine (闢廬(秋尾)社) - Hara

Shimo-Jūsansho (下十三所)

- Yatsurugi Shrine (八剣神社)

- Osaka Shrine (小坂社)

- Sakinomiya Shrine (先宮神社)

- Ogimiya Shrine (荻宮社)

- Tatsuya Shrine (達屋神社)

- Sakamuro Shrine (酒室神社)

- Geba Shrine (下馬社)

- Mimuro Shrine (御室社)

- Okama Shrine (御賀摩社)

- Isonami Yama-no-Kami (磯並山神)

- Takei Ebisu / Emishi (武居会美酒)

- Gōdono Nagabeya (神殿中部屋)

- Nagahashi Shrine (長廊神社)

Lower Shrine

Priests

Before the Meiji period, various local clans (many of which traced themselves to the gods of the region) served as priests of the shrine, as in other places. After hereditary priesthood was abolished, government-appointed priests took the place of these sacerdotal families.

Kamisha

These are the high priestly offices of the Kamisha and the clans which occupied said positions.[176][177][178]

- Ōhōri (大祝, also ōhafuri) - Suwa clan (諏訪(諏方)氏)

- The high priest of the Kamisha, considered to be an arahitogami, a living embodiment of Suwa Myōjin, and thus, an object of worship.[179] The Suwa were in legend considered to be Suwa Myōjin's descendants,[17][105] although historically they are probably descended from the same family as the Kanasashi of the Shimosha: that of the kuni-no-miyatsuko of Shinano, governors appointed by the Yamato state to the province.[180][181][182]

- Jinchōkan (神長官) or Jinchō (神長) - Moriya clan (守矢氏)

- The head of the five assistant priests (五官 gogan) serving the ōhōri and overseer of the Kamisha's religious rites, considered to be descended from the god Moreya, who in myth originally resisted Suwa Myōjin's entry into the region before becoming his priest and collaborator.[17][105] While officially subservient to the ōhōri, the Moriya iinchōkan was in reality the one who controlled the shrine's affairs, due to his full knowledge of its ceremonies and other rituals (which were transferred only to the heir to the position) and his exclusive ability to summon (as well as dismiss) the god(s) Mishaguji, worshipped by the Moriya since antiquity.[183][184]

- Negi-dayū (禰宜大夫) - Koide clan (小出氏), later Moriya clan (守屋氏)

- The office's original occupants, the Koide, claimed descent from Yakine-no-mikoto (八杵命), one of Suwa Myōjin's divine children.[178] The Negi-dayū Moriya meanwhile claimed descent from a supposed son of Mononobe no Moriya who fled to Suwa and was adopted into the Jinchō Moriya clan.[185]

- Gon-(no-)hōri (権祝) - Yajima clan (矢島氏)

- The Yajima clan claimed descent from another of Suwa Myōjin's offspring, Ikeno'o-no-kami (池生神).[178]

- Gi-(no-)hōri (擬祝) - Koide clan, later Itō clan (伊藤氏)

- Soi-no-hōri (副祝) - Jinchō Moriya clan, later Nagasaka clan (長坂氏)

Shimosha

The following meanwhile were the high priestly offices of the Shimosha.[186][177][178]

- Ōhōri (大祝) - Kanasashi clan (金刺氏)

- The high priest of the Shimosha. The original occupants of the office, the Kanasashi, traced themselves to the clan of the kuni-no-miyatsuko of Shinano, descendants of Takeiotatsu-no-mikoto (武五百建命), a grandson (or later descendant) of the legendary Emperor Jimmu's son, Kamuyaimimi-no-mikoto.[186] During the Muromachi period, the Kanasashi, after a long period of warfare with the Suwa, were finally defeated and driven out of the region, at which the office became effectively defunct.[187]

- Takei-no-hōri (武居祝) - Imai clan (今井氏)

- The head of the Shimosha's gogan. The occupants of this office, a branch of the Takei clan (武居氏), traced themselves to Takei-ōtomonushi (武居大伴主), another local deity who (like Moreya) originally fought against Suwa Myōjin before being defeated and submitting to him.[188][189][190] After the fall of the Kanasashi, this priest came to assume the functions once performed by the Kanasashi ōhōri.[191][187]

- Negi-dayū (禰宜大夫) - Shizuno clan (志津野氏), later Momoi clan (桃井氏)

- Gon-(no-)hōri (権祝) - Yamada clan (山田氏), later Yoshida clan (吉田氏)

- Gi-(no-)hōri (擬祝) - Yamada clan

- Soi-no-hōri (副祝) - Yamada clan

In addition to these were lesser priests, shrine monks (shasō), shrine maidens, other officials and shrine staff.

Branch shrines

Suwa-taisha is the head shrine of the Suwa network of shrines, composed of more than 10 thousand individual shrines.[3]

Festivals

Suwa Taisha is the focus of the famous Onbashira festival, held every six years. The Ofune Matsuri, or boat festival, is held on August 1, and the Senza Matsuri festival is held on February 1 to ritually move the spirits between the Harumiya and Akimiya shrines.

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 Aston, William George (1896). "

- ↑ Tanigawa, Kenichi, ed. (1987). Nihon no kamigami: Jinja to seichi, vol. 9: Mino, Hida, Shinano (日本の神々―神社と聖地〈9〉美濃・飛騨・信濃). Hakusuisha. p. 129. ISBN 978-4560025093. (in Japanese)

- 1 2 "Shrines and Temples". Suwa-taisha shrine. Japan National Tourist Association. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- ↑ "Suwa-taisha (諏訪大社)". 長野県下諏訪町の観光情報.

- ↑ "Suwa Grand Shrine (Suwa Taisha)". Go! Nagano (Nagano Prefecture Official Tourism Guide).

- ↑ Grumbach, Lisa (2005). Sacrifice and Salvation in Medieval Japan: Hunting and Meat in Religious Practice at Suwa Jinja. Stanford University. pp. 150–151.

- ↑ Grumbach (2005). pp.150-151.

- 1 2 Imai, Nogiku; Kitamura, Minao; Tanaka, Motoi; Nomoto, Sankichi; Miyasaka, Mitsuaki (2017). Kodai Suwa to Mishaguji Saiseitai no Kenkyu (古代諏訪とミシャグジ祭政体の研究) (Reprint ed.). Ningensha. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-4908627156.

- ↑ Grumbach (2005). pp. 153-154.

- ↑ "ミシャグジ (Mishaguji)". 日本の神様辞典 (Nihon no Kamisama Jiten).

- ↑ Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (1995). Suwa Shishi, vol. 01 (諏訪市史 上 原始・古代・中世) (in Japanese). p. 689.

- ↑ Tanigawa (1987). p. 185.

- ↑ Chamberlain, Basil (trans.) (1882). Section XXXII.—Abdication of the Deity Master-of-the-Great-Land. A translation of the "Ko-ji-ki" or Records of Ancient Matters. Yokohama: Lane, Crawford & Co.

- ↑ Jean Herbert (18 October 2010). Shinto: At the Fountainhead of Japan. Routledge. p. 437. ISBN 978-1-136-90376-2.

- 1 2 Michael Ashkenazi (1 January 2003). Handbook of Japanese Mythology. ABC-CLIO. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-57607-467-1.

- ↑ "先代舊事本紀卷第三". 私本 先代舊事本紀.

- 1 2 3 Moriya, Sanae (1991). Moriya-jinchō-ke no ohanashi (守矢神長家のお話し). In Jinchōkan Moriya Historical Museum (Ed.). Jinchōkan Moriya Shiryōkan no shiori (神長官守矢資料館のしおり) (Rev. ed.). pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Miyasaka, Mitsuaki (1992). 諏訪大社の御柱と年中行事 (Suwa-taisha no Onbashira to nenchu-gyōji). Kyōdo shuppansha. pp. 88–93. ISBN 978-4-87663-178-0.

- ↑ Oh, Amana ChungHae (2011). Cosmogonical Worldview of Jomon Pottery. Sankeisha. p. 157. ISBN 978-4-88361-924-5.

- ↑ Yazaki (1986). pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Rekishi REAL Henshūbu (歴史REAL編集部) (ed.) (2016). Jinja to kodai gōzoku no nazo (神社と古代豪族の謎). Yosensha. p. 39. ISBN 978-4800308924. (in Japanese)

- ↑ Takei (1999). 129–130.

- ↑ Hanawa, Hokiichi, ed. (1914). Suwa Daimyōjin Ekotoba (諏訪大明神繪詞). Zoku Gunsho-ruijū (続群書類従). 3. Zoku Gunsho-ruijū Kanseikai. p. 534. (in Japanese)

- ↑ Breen, John and Teeuwen, Mark (eds.) (2000). Shinto in History: Ways of the Kami. University of Hawaii Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-8248-2363-4.

- ↑ Dorson, Richard M. (2012). Folk Legends of Japan. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 145ff. ISBN 978-1-4629-0963-6.

- ↑ Orikuchi, Shinobu (1929–1930). "古代人の思考の基礎 (Kodaijin no shikō no kiso)". Aozora Bunko.

- 1 2 Hanawa, ed. (1914). Suwa Daimyōjin Ekotoba. pp. 521–522.

- ↑ Yamada, Taka. Shinto Symbols (PDF). p. 8.

- ↑ "大祝有員 (Ōhōri Arikazu)". Official website of Suwa City (in Japanese).

- ↑ Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (1995). Suwa Shishi (The History of Suwa City), vol. 1 (諏訪市史 上巻 原始・古代・中世). Suwa. p. 683-684, 711-713.

- ↑ Ihara, Kesao (2008-03-31). "鎌倉期の諏訪神社関係史料にみる神道と仏道 : 中世御記文の時代的特質について (Shinto and Buddhism as Depicted in Historical Materials Related to Suwa Shrines of the Kamakura Period : Temporal Characteristics of Medieval Imperial Writings)". Bulletin of the National Museum of Japanese History. 139: 157–185. (in Japanese)

- ↑ "諏方氏 (Suwa Clan)". Official website of Suwa City (in Japanese).

- ↑ Jin/Miwa-ke keizu (神家系図), in Suwa Kyōikukai (諏訪教育会), ed. (1931). 諏訪史料叢書 巻28 (Suwa shiryō-sōsho, vol. 28). Suwa: Suwa Kyōikukai. (in Japanese)

- ↑ Ōhōri-bon Jin/Miwa-shi keizu (大祝本神氏系図), cited in Kanai, Tenbi (1982). Suwa-shinkō-shi (諏訪信仰史). Meicho Shuppan. pp. 107, 190.

- 1 2 3 4 "Suwa Shinkō". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- ↑ "守屋山と神体山". 諏訪大社と諏訪神社. 八ヶ岳原人.

- ↑ "Suwa Taisha Shrine". JapanVisitor Japan Travel Guide.

- 1 2 3 Yazaki, Takenori, ed. (1986). 諏訪大社 (Suwa-taisha). Ginga gurafikku sensho. 4. Ginga shobō. p. 96. (in Japanese)

- ↑ Tanigawa, ed. (1987). p. 132-135.

- ↑ Tanigawa, ed. (1987). p. 135-136.

- 1 2 3 Inoue, Takami (2003). "The Interaction between Buddhist and Shinto Traditions at Suwa Shrine." In Rambellli, Fabio; Teuuwen, Mark (ed.). Buddhas and Kami in Japan: Honji Suijaku as a Combinatory Paradigm. Routledge. p. 350.

- ↑ Muraoka (1969). p. 27.

- ↑ Tanigawa (1987). p. 142.

- ↑ Oh (2011). pp. 155-163.

- ↑ Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (1995). pp. 684-685, 687.

- ↑ Miyasaka, M. (1987). pp. 23–30.

- ↑ Tanigawa (1987). pp. 191–194.

- ↑ Oh (2011). pp. 160-163.

- ↑ Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (1995). "Suwa-jinja Kamisha Shimosha (諏訪神社上社・下社)". p. 686.

- 1 2 3 Miyasaka (1992). pp. 8-11.

- ↑ Grumbach (2005). pp. 156-157.

- ↑ Grumbach (2005). p. 157.

- ↑ Grumbach (2005). pp. 156-158.

- ↑ "青塚古墳 (Aozuka Kofun)". Shimosuwa Town Official Website.

- ↑ Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (1995). pp. 619-620.

- ↑ Grumbach (2005). p. 158.

- ↑ Ihara (2008). pp. 260-262.

- ↑ Fukushima, Masaki (福島正樹). "信濃古代の通史叙述をめぐって (Shinano kodai no tsūshi jojutsu wo megutte)". 科野太郎の古代・中世史の部屋. Retrieved 2017-09-24.

- ↑ Itō, Rintarō (伊藤麟太朗) (1994). "所謂『阿蘇氏系図』について (Iwayuru 'Aso-shi Keizu' ni tsuite)". Shinano (信濃). Shinano Shigakukai (信濃史学会). 46 (8): 696–697.

- ↑ Murasaki, Machiko (村崎真智子) (1996). "異本阿蘇氏系図試論 (Ihon Aso-shi keizu shiron)". Hito, mono, kotoba no jinruigaku: Kokubu Naoichi Hakushi beiju kinen ronbunshū (ヒト・モノ・コトバの人類学. 国分直一博士米寿記念論文集). Keiyūsha (慶友社): 202–218.

- ↑ For a contrary viewpoint, cf. Hōga, Yoshio (宝賀寿男) (2006). "村崎真智子氏論考「異本阿蘇氏系図試論」等を読む".

- ↑ Grumbach (2005). pp. 157-158.

- ↑ Oh (2011). pp. 157-158.

- ↑ Grumbach (2005). p. 161.

- ↑ Miyasaka, M. (1987). p. 29.

- ↑ Yazaki (1986). p. 22.

- ↑ Miyasaka (1992). p. 11.

- 1 2 Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (1995). pp. 687–689.

- ↑ Miyasaka, M. (1987). pp. 17–26.

- ↑ Ōwa (1990). pp. 212–214.

- ↑ Oh (2011). pp. 157-158.

- ↑ Miyasaka, M. (1987). p. 19.

- ↑ Ōwa (1990). pp. 213, 220

- ↑ Ōwa (1990). p. 19.

- ↑ Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (1995). p. 689.

- ↑ Grumbach (2005). p. 158.

- 1 2 "南方刀美神社二座(建御名方富命神)". 神社資料データベース (Shinto Jinja Database). Kokugakuin University.

- 1 2 "

- ↑ Miyasaka (1992). pp. 11-12.

- ↑ "

- ↑ Miyasaka (1992). p. 12.

- ↑ "売神祝ノ印". Shimosuwa Town Official Website.

- ↑ Grumbach (2005). pp. 157-158.

- ↑ Miyasaka (1992). pp. 12-13.

- ↑ Grumbach (2005). p. 159.

- ↑ Miyasaka (1992). pp. 12-13.

- ↑ Miyasaka (1987). pp. 37-38.

- 1 2 Suwa Kyōikukai (1938). 諏訪史年表 (Suwa Shinenpyō). Nagano: Suwa Kyōikukai. p. 11.(in Japanese)

- ↑ Miyasaka (1987). p. 35.

- ↑ "大祝有員 (Ōhōri Arikazu)". Official website of Suwa City (in Japanese).

- ↑ "諏方氏 (Suwa Clan)". Official website of Suwa City (in Japanese).

- ↑ Kishi, Shōzō (trans.) (1967). Shintōshū (神道集). Tōyō Bunko (東洋文庫) vol. 94. Heibonsha. pp. 49–56. ISBN 978-4-582-80094-4.

- ↑ Suwa, Enchū (1914). 諏訪大明神繪詞 (Suwa-daimyōjin ekotoba) in Hanawa, Hoki'ichi (ed.), 続群書類従 (Zoku Gunsho-Ruijū). Tokyo: Zoku Gunsho-Ruijū Kanseikai. pp. 499–501. (Original work written 1356) (in Japanese)

- ↑ Miyasaka (1992). p. 14.

- ↑ Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (1995). pp. 711-713.

- ↑ "Nationwide List of Ichinomiya," p. 2.; retrieved 2011-08-010

- ↑ Tanigawa (1987). p. 130.

- ↑ "Engishiki, vol. 10 (延喜式 第十巻)". Japanese Historical Text Initiative (JHTI).

- ↑ Grumbach (2005). pp. 159-160.

- ↑ Minamoto no Tsuneyori (1915). Sasagawa, Taneo, ed. Sakeiki (左経記). Shiryō tsūran (史料通覧). 4. Nihon shiseki hozon-kai. p. 43. (original work written 1016-1036) (in Japanese)

- ↑ Kim, Yung-Hee (1994). Songs to Make the Dust Dance: The Ryōjin Hishō of Twelfth-century Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 144–145a. ISBN 978-0-520-08066-9.

- ↑ Miyachi, Naokazu (1931). 諏訪史 第二卷 後編 (Suwa-shi, vol. 2, part 2). 信濃教育会諏訪部会 (Shinano kyōikukai Suwa-bukai). pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Miyasaka, Yūshō (1987). "Kami to hotoke no yūgō (上と仏の融合)." In Ueda; Gorai; Ōbayashi; Miyasaka, M.; Miyasaka, Y. 御柱祭と諏訪大社 (Onbashira-sai to Suwa-taisha). Nagano: Chikuma Shobō. pp. 146–153. ISBN 978-4-480-84181-0.

- ↑ Miyasaka, Y. (1987). pp. 168–171.

- 1 2 3 4 Inoue (2003). p. 352.

- ↑ Grumbach (2005). p. 176.

- ↑ Inoue (2003). p. 352.

- 1 2 Yazaki (1986). p. 25.

- ↑ Grumbach (2005). pp. 176-180.

- ↑ Grumbach (2005). pp. 181-185.

- ↑ Muraoka (1969). p. 112.

- ↑ Grumbach (2005). pp. 177-178.

- ↑ Grumbach (2005). p. 185.

- ↑ Miyasaka, Mitsuaki (1987). "Kyodai naru kami no kuni. Suwa-shinkō no tokushitsu (強大なる神の国―諏訪信仰の特質)." In Ueda; et al. Onbashira-sai to Suwa-taisha. pp. 51–54.

- ↑ Miyasaka, Mitsuaki (1991). "Sanagi-suzu (サナギ鈴)." In Jinchōkan Moriya Historical Museum (Ed.). Jinchōkan Moriya Shiryōkan no shiori (Rev. ed.). pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (1995). pp. 811-814.

- ↑ Suwa Nobushige Gejō (諏訪信重解状), in Suwa Kyōikukai (諏訪教育会), ed. (1931). 諏訪史料叢書 巻15 (Suwa shiryō-sōsho, vol. 15) (in Japanese). Suwa: Suwa Kyōikukai.

- ↑ Kanai (1982). p. 14

- 1 2 3 Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (1995). p. 814.

- ↑ Brinkley, Frank; Kikuchi, Dairoku (1915). A History of the Japanese People from the Earliest Times to the End of the Meiji Era. New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Co. pp. 390–391.

- ↑ "諏訪氏 (Suwa-shi)". 風雲戦国史-戦国武将の家紋- 播磨屋. (in Japanese)

- ↑ "戦国時代の諏訪の武将達". リゾートイン レア・メモリー. (in Japanese)

- ↑ Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (1995). p. 696.

- ↑ Fukuda, Akira; Tokuda, Kazuo; Nihonmatsu, Yasuhiro (2015). 諏訪信仰の中世―神話・伝承・歴史 (Suwa-Shinko no Chusei: Shinwa, Densho, Rekishi). Miyai Shoten. pp. 130–132. ISBN 978-4838232888.

- ↑ Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (1995). p. 815.

- ↑ Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (1995). pp. 814-820.

- ↑ "Kanasashi Okiharu (金刺興春)". Nandemo Suwa Hyakka (なんでも諏訪百科). Suwa City Museum.

- ↑ Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (1995). p. 1015.

- ↑ Turnbull, Stephen (2013). Kawanakajima 1553–64: Samurai power struggle. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 26–28. ISBN 978-1846036521.

- 1 2 3 Turnbull, Stephen (2012). Nagashino 1575: Slaughter at the barricades. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 978-1782002550.

- ↑ Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (1995). p. 1022.

- ↑ Turnbull (2013). p. 28.

- ↑ Turnbull (2013). pp. 28-29.

- 1 2 Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (1995). p. 1015.

- ↑ Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (1995). p. 1016.

- 1 2 Tanigawa (1987). p. 137, 152-153.

- 1 2 3 Yazaki (1986). p. 26.

- ↑ Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (1995). pp. 1023-1025.

- ↑ Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (1995). pp. 1014-1015.

- ↑ "山梨の文化財ガイド (Guide to Cultural Assets of Yamanashi)". Official website of Yamanashi Prefecture.

- ↑ Turnbull (2012). p. 156.

- ↑ Furukawa (1988). p. 148.

- ↑ "法華寺(ほっけじ)". homtaすわ.

- ↑ "御柱の歴史~諏訪市博物館「御柱とともに」より~". 御柱祭いくぞやい. Suwa City.

- ↑ Inoue (2003). pp. 357-362.

- ↑ Inoue (2003). pp. 362-371.

- ↑ Inoue (2003). p. 371.

- ↑ Kitamura, Minao (2017). "「ミシャグジ祭政体」考 ("Mishaguji Saiseitai"-kō)." In Kodai Buzoku Kenkyūkai (Ed.), p. 105.

- ↑ Tanigawa, ed. (1987). pp. 139-140.

- ↑ Tanigawa, ed. (1987). p. 140.

- ↑ Miyasaka, M. (1987). p. 38.

- ↑ Tanigawa, ed. (1987). p. 138.

- ↑ Tanigawa, ed. (1987). p. 139.

- ↑ 旧上社大祝の居館・神殿跡 (Kyū-Kamisha Ōhōri no kyokan - Gōdono-seki) (Sign). Suwa Taisha Kamisha Maemiya: Ankokuji Shiyūkai (安国寺史友会).

- ↑ Tanigawa, ed. (1987). p. 139.

- ↑ Imai et al. (2017). pp. 286-287.

- 1 2 "昭和初期の前宮". 諏訪大社と諏訪神社(附・神社参拝記). 八ヶ岳原人.

- ↑ Imai et al. (2017). pp. 32-33.

- 1 2 "茅野駅周辺散策マップ". Beauty Salon MAY Home Page.

- ↑ Gotō, Sōichirō (1990). 神のかよい路: 天竜水系の世界観. Tankōsha. p. 228. ISBN 978-4473011329.

- ↑ Imai et al. (2017). pp. 34-36.

- ↑ "折橋子之社 (茅野市北山糸萱)". 諏訪大社と諏訪神社(附・神社参拝記). 八ヶ岳原人.

- ↑ "(伝)八坂刀売命陵". 諏訪大社と諏訪神社(附・神社参拝記). 八ヶ岳原人.

- ↑ "「水眼の清流」 水眼川 茅野市前宮". 諏訪大社と諏訪神社(附。神社参拝記). 八ヶ岳原人.

- ↑ Tanigawa, ed. (1987). p. 139.

- ↑ Google. "峰の湛" (Map). Google Maps. Google.

- ↑ "峯湛(諏訪七木)". 諏訪大社と諏訪神社(附・神社参拝記). 八ヶ岳原人.

- ↑ 峯のたたえ. Suwa Taisha Kamisha Maemiya: Ankokuji Shiyūkai (安国寺史友会).

- ↑ 市指定天然記念物 峰たたえのイヌザクラ 昭和六十三年七月二十九日指定. Suwa Taisha Kamisha Maemiya: Chino-shi Kyōiku Iinkai (茅野市教育委員会). January 1989.

- ↑ Imai et al. (2017). pp. 97-108, 115-125.

- ↑ Oh (2011). pp. 170-176.

- ↑ Miyasaka (1992). pp. 91-92.

- ↑ Miyasaka (1992). pp. 88-91.

- ↑ Miyasaka (1992). pp. 94-99.

- ↑ Miyasaka (1992). p. 134.

- ↑ Tanigawa (1987). pp. 135-136.

- 1 2 Ōta, Akira (1926). 諏訪神社誌 第1巻 (Suwa-jinja-shi: Volume 01). Nagano: Kanpei-taisha Suwa-jinja fuzoku Suwa-myōjin-kōsha. pp. 225–239. (in Japanese)

- 1 2 3 4 Ōta, Akira (1924). 日本國誌資料叢書 信濃 (Nihon kokushi shiryō sōsho: Shinano). Tokyo: Isobe Kōyōdō. p. 164.

- ↑ Rekishi REAL Henshūbu (歴史REAL編集部) (ed.) (2016). pp. 40-42.

- ↑ Inoue (2001). p. 345.

- ↑ Kanai, Tenbi (1982). Suwa-shinkō-shi (諏訪信仰史). Meicho Shuppan. pp. 14, 106–109.

- ↑ Miyasaka, Mitsuaki (1992). 諏訪大社の御柱と年中行事 (Suwa-taisha no Onbashira to nenchu-gyōji). Kyōdo shuppansha. p. 7. ISBN 978-4876631780. (in Japanese)

- ↑ Moriya (1991). pp. 4-5.

- ↑ Miyasaka, M. (1987). p. 25-27.

- ↑ Ōta (1926). p. 227.

- 1 2 Tanigawa (1987). pp. 142-143.

- 1 2 "Kanasashi-shi (金刺氏)". harimaya.com.

- ↑ Ōta (1926). pp. 15-16.

- ↑ Miyasaka, M. (1987). p. 22.

- ↑ Fukuyama, Toshihisa, ed. (1912). 信濃史蹟 (Suwa shiseki). Shinano shinbunsha. p. 18-19. (in Japanese)

- ↑ Suwa Kyōikukai (1938). 諏訪史年表 (Suwa Shinenpyō). Nagano: Suwa Kyōikukai. p. 74.(in Japanese)

Bibliography

- Grumbach, Lisa (2005). Sacrifice and Salvation in Medieval Japan: Hunting and Meat in Religious Practice at Suwa Jinja (PhD). Stanford University.

- Inoue, Takami (2003). "The Interaction between Buddhist and Shinto Traditions at Suwa Shrine." In Rambellli, Fabio; Teuuwen, Mark (eds.). Buddhas and Kami in Japan: Honji Suijaku as a Combinatory Paradigm. Routledge. ISBN 978-1134431236.

- Jinchōkan Moriya Historical Museum, ed. (2015). 神長官守矢資料館のしおり (Jinchōkan Moriya Shiryōkan no shiori) (in Japanese) (3rd ed.).

- Kanai, Tenbi (1982). 諏訪信仰史 (Suwa-shinkō-shi) (in Japanese). Meicho Shuppan. ISBN 978-4626001245.

- Kodai Buzoku Kenkyūkai, ed. (2017). 古代諏訪とミシャグジ祭政体の研究 (Kodai Suwa to Mishaguji Saiseitai no Kenkyū) (in Japanese) (Reprint ed.). Ningensha. ISBN 978-4908627156.

- Miyasaka, Mitsuaki (1992). 諏訪大社の御柱と年中行事 (Suwa-taisha no Onbashira to nenchu-gyōji) (in Japanese). Kyōdo shuppansha. ISBN 978-4-87663-178-0.

- Muraoka, Geppo (1969). 諏訪の祭神 (Suwa no saijin) (in Japanese). Tokyo: Yūzankaku-shuppan.

- Oh, Amana ChungHae (2011). Cosmogonical Worldview of Jomon Pottery. Sankeisha. ISBN 978-4-88361-924-5.

- Suwa Shishi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (1995). 諏訪市史 上巻 原始・古代・中世 (Suwa Shishi, vol. 1: Genshi, Kodai, Chūsei) (in Japanese). Suwa.

- Tanigawa, Kenichi, ed. (1987). 日本の神々―神社と聖地〈9〉美濃・飛騨・信濃 (Nihon no kamigami: Jinja to seichi, vol. 9: Mino, Hida, Shinano) (in Japanese). Hakusuisha. ISBN 978-4-560-02509-3.

- Ueda, Masaaki; Gorai, Shigeru; Miyasaka, Yūshō; Ōbayashi, Taryō; Miyasaka, Mitsuaki (1987). 御柱祭と諏訪大社 (Onbashira-sai to Suwa Taisha) (in Japanese). Nagano: Chikuma Shobō. ISBN 978-4-480-84181-0.

- Yazaki, Takenori, ed. (1986). 諏訪大社 (Suwa Taisha). Ginga gurafikku sensho (in Japanese). 4. Ginga shobō.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Suwa Taisha. |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)