Scottish Conservatives

Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party Pàrtaidh Tòraidheach na h-Alba Scots Conservative an Unionist Pairty | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leader | Ruth Davidson MSP |

| Chairman | Rab Forman MBE, WS |

| Deputy leader | Jackson Carlaw MSP |

| Founded | 1965 |

| Headquarters |

67 Northumberland Street Edinburgh EH3 6JG |

| Youth wing | Conservative Future Scotland |

| Membership (2012) | 11,000[1] |

| Ideology |

Conservatism[2] British unionism Economic liberalism[2] |

| Political position | Centre-right[3][4] |

| National affiliation | Conservative Party |

| European affiliation | Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists |

| International affiliation | International Democrat Union |

| European Parliament group | European Conservatives and Reformists |

| Colours | Blue |

| House of Commons (Scottish seats) |

13 / 59 |

| Scottish Parliament |

31 / 129 |

| European Parliament (Scottish seats) |

1 / 6 |

| Local government in Scotland[5] |

275 / 1,227 |

| Website | |

|

www | |

The Scottish Conservatives (Scottish Gaelic: Pàrtaidh Tòraidheach na h-Alba), officially the Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party, is the part of the Conservative Party in the United Kingdom that operates in Scotland. Describing itself as a “patriotic party of the Scottish centre-right”,[6] it is the second-largest party in the Scottish Parliament and Scottish local government. It also sends the second-largest Scottish representation to the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, after the SNP in each respect.

The party is informally known as the Scottish Tories, due to the Conservative Party's historic links with the Tory Party. The leader of the Scottish Conservatives is Ruth Davidson MSP, who has held the post since 2011.

The modern Scottish Conservative Party was established in 1965 with the merger of the Unionist Party into the Conservative Party in England and Wales. The Unionist Party, as with the Conservative and Unionist Party in England and Wales, was formed in 1912 by the merger of the Conservatives and Liberal Unionists, and existed as the dominant force in Scottish politics from the 1930s to the late 1950s.[7] While organising itself as a separate party in Scotland, Unionists took the Conservative whip in the UK Parliament, with Bonar Law and Alec Douglas-Home, then Unionist Members of Parliament becoming leader of the Conservative Party and Prime Minister.

Unionists won the most seats in Scotland in the 1955 general election and gained a majority of the Scottish vote - the second time this was achieved by a political party since the introduction of universal suffrage. They had also achieved a majority of the vote 24 years earlier in the 1931 general election with 54.4%. In the 1959 election, Unionist candidates won the most votes as a sum total in Scotland though not a majority of seats due to First Past the Post electoral system; since then the Labour Party went on to dominate Scottish politics for the remainder of the 20th century.

The 1997 general election saw the party fail to return any MPs in Scottish constituencies and returned only one MP in the 2001, 2005, 2010, and 2015 elections. In the 2017 UK general election, the party increased its number of MPs to 13 on 28.6 per cent of the popular vote - its best performance since 1983 and in terms of votes since 1979. In the devolved Scottish Parliament, the Scottish Conservatives ranked in third place until the 2016 election. It is currently the largest opposition party, with 31 of 129 seats. It also holds one of six seats for the Scotland constituency of the European Parliament.

History

Scottish Conservatism pre-1912

Prior to 1912, the Conservative Party organised in Scotland. With the emergence of mass party political organisations in the second half of the 19th century, distinct organisations emerged in Scotland. The voluntary party organisation, the National Union of Conservative Associations for Scotland (mirroring the National Union of Conservative Associations) emerged in 1882, organising a distinct Conservative conference in Scotland. [8]

A previous organisation, the Scottish National Constitutional Association, existed from 1867, with the patronage of UK party leader Benjamin Disraeli. The Scotsman newspaper reported that following the 1874 election "Conservative Clubs and Working Men's Conservative Associations have spring up like mushrooms in all parts of [Scotland]".[9]

From the Representation of the People Act 1884 until 1918, the Liberal Party was the dominant political force in Scotland, operating in a largely two-party system with the Scottish Conservatives. In 1886, the Liberal Unionists had broken away from the Liberal Party in opposition to William Gladstone's proposals for Irish Home Rule. Joint Liberal Unionist and Conservative candidates were run across the United Kingdom, but with the organisations of these parties remaining separate.

The Unionist Party (1912-1965)

Following the merger of the Conservatives and Liberal Unionists to create the modern Conservative and Unionist Party in England and Wales, a committee was formed of the National Union of Conservative Associations for Scotland and regional Liberal Unionist associations which recommended a merger in Scotland. This was agreed in December 1912, creating the Scottish Unionist Association and the Unionist Party.[10]

From 1918 and through the 1920s, the Labour Party became more prominent, displacing the Liberals as one of the two main parties in Scottish politics. The Unionist Party had a number of electoral successes, topping the poll in Scotland in a number of elections from the 1930s to 1950s. During the period of its existence, the Unionist Party produced two Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom - Andrew Bonar Law and Alec Douglas-Home - and uniquely among parties in the post-war period, achieved more than half of the popular vote within Scotland in the 1931 general election and 1955 general election.

While taking the Conservative whip in the House of Commons, the Unionist Party had a lengthy "unionist-nationalist" tradition, emphasising its Scottish identity within the United Kingdom and the British Empire. This was represented by elected members such as John Buchan (who said "I believe every Scotsman should be a Scottish nationalist") [11]) and those former Unionists who in 1932 founded the pro-home rule Scottish Party (which later merged with the National Party of Scotland to form the Scottish National Party).

Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party

Following a decline in performance, coming second to the Labour Party at the 1959 general election and 1964 general election, the Unionist Party proposed a number of reforms which involved amalgamation with the Conservative and Unionist Party in England and Wales - taking place in 1965. The modern Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party, as part of the wider UK Conservative Party, came into existence from this point.[12]

However its electoral fortunes continued to decline throughout the 1960s. Following Harold Wilson's failure to obtain a Labour majority in February 1974, a second general election was held in October of the same year which saw the party decline to below 25% of the vote and drop from 21 seats to 16. At the same time, the SNP were to gain an unprecedented 11 MPs, unseating a number of Conservative MPs in rural constituencies.

The party's fortunes recovered somewhat in 1979 under the leadership of Margaret Thatcher, but her tenure as Prime Minister was to see the party's fortunes drop further from holding 22 seats in 1979 to 10 in 1987. The party increased its share of the vote and number of MPs to 11 in 1992 under John Major's leadership before dropping to 17.5% of the popular vote and failing to have any MPs returned from Scotland in 1997. It continued to return only a single MP from Scottish constituencies at the 2001, 2005, 2010 and 2015 general elections, before winning 13 seats in 2017.

Following the 2010 general election performance, the party commissioned a review under Lord Sanderson of Bowden to consider the party's future organisation. The Sanderson Commission's report recommended a single Scottish leader (replacing a leader of the Scottish Parliamentary group), reforms to governance and constituency structures, the creation of regional campaigning centres, greater focus on policy development and a new membership and fundraising drive.[13]

Scottish devolution

The party's commitments to a devolved Scottish Assembly were to decline under the leadership of Margaret Thatcher. Previously the party had offered some support for a Scottish Assembly, including in the so-called Declaration of Perth in 1968 under UK party leader Edward Heath. John Major, while endorsing further powers for the Scottish Grand Committee and the Scottish Office did not support a devolved parliament. With the Labour Party's victory in 1997, referendums on devolution were organised in Scotland and Wales, both receiving agreement that devolved legislatures should be formed.

In 1999, the first elections to a devolved Scottish Parliament were held. Following the Conservatives electoral wipe-out in Scotland in 1997, devolution provided the party with a number of parliamentary representatives in Scotland. Less than a year following the first Scottish Parliament election, a 2000 by-election was held in the Ayr constituency with John Scott winning the seat from Labour.

In the party leadership elections in 2011, the previous deputy leader Murdo Fraser proposed disbanding the party and creating a new Scottish party of the centre-right, similar to the previous Unionist Party and compared this arrangement to the relationship between the Christian Social Union in Bavaria and the Christian Democratic Union in Germany. The move was opposed by the other three candidates.[14][15] Victory went to the newly elected MSP Ruth Davidson who suggested that she would oppose further devolution beyond the new powers proposed by the Calman Commission.

The party was one of the three main Scottish political parties to join together in the Better Together campaign supporting Scotland remaining as part of the United Kingdom in the Scottish independence referendum, 2014. Following the referendum, and a Conservative majority government was returned in the 2015 general election with David Mundell appointed Secretary of State for Scotland, replacing the previous Liberal Democrat incumbents who served during the 2010-15 Coalition government. The UK Government set about implementing the recommendations of the cross-party Smith Commission, giving a range of new powers to the Scottish Parliament.

Recent elections

2011 Scottish Parliament election

Annabel Goldie led the party into the 2011 Scottish Parliament election, having successfully campaigned in budget negotiations with the minority SNP Scottish Government for a number of concessions over the 2007-11 Scottish Parliament. This had resulted in commitments to 1,000 extra police officers, four-year council tax freeze and £60m town regeneration fund. [16]

With an SNP majority delivered, the Scottish Conservatives were reduced from 17 seats to 15, losing the Edinburgh Pentlands constituency to the SNP, seeing notional loses in Eastwood and Dumfriesshire to Labour. Following the election, Annabel Goldie resigned as leader and a leadership election was held in November 2011 - the first to appoint a Leader of the Scottish Conservatives, rather than the Scottish Parliament group, as required by the Sanderson Commission. Ruth Davidson was returned, beating the original front-runner and former deputy leader Murdo Fraser.

Davidson drove forward a number of the Sanderson Commission's reforms, including replacing the party's Banyan (or Indian Fig) tree logo with a "union saltire".

2015 UK general election

The Conservatives made little advance at the 2015 UK general election compared to 2010, with Scotland's sole Conservative MP David Mundell holding on to his Dumfriesshire, Clydesdale and Tweeddale constituency with a reduced majority of just 798 votes ahead of the SNP's Emma Harper. The Conservatives made no seat gains at the election in Scotland, with Conservative targets such as Argyll and Bute; West Aberdeenshire and Kincardine and Angus being won by the Scottish National Party with an increased majority compared to 2010. In spite of this, the Conservatives narrowly missed out on having 2 MP's elected in Scotland, missing out in the Berwickshire, Roxburgh and Selkirk constituency by only 328 votes behind the SNP's Calum Kerr: this was the most marginal result in Scotland and the eighth most marginal result in the United Kingdom.

2016 Scottish Parliament election

At the 2016 Scottish Parliament election the Scottish Conservative campaign focused on providing strong opposition to the SNP government in Scotland, unequivocally opposing calls for a second referendum on Scottish independence. The party manifesto focused on freezing business tax rates to promote economic growth and greater employment opportunities; investing in mental health treatment over the course next parliament; a commitment to building 100,000 affordable homes within 5 years and a re-introduction of the Right to Buy scheme in Scotland.[17] The Scottish Conservatives were the only major party in Scotland to oppose higher taxes to the rest of the United Kingdom during the campaign as tax reductions came in force across the rest of the UK which were opposed by the SNP, Labour and Liberal Democrats.[18]

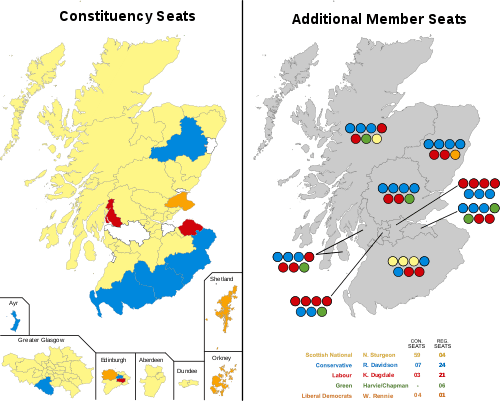

At the election the party saw major gains, particularly on the regional list vote. The Conservatives doubled their representation in the Scottish Parliament by taking 31 seats (compared to just 15 in 2011), making them the leading opposition party in the Scottish Parliament ahead of Scottish Labour. On the constituency element of the vote the Conservatives held on to their three first past the post constituency seats (Ayr; Ettrick, Roxburgh and Berwickshire and Galloway and West Dumfries), making gains in Aberdeenshire West; Dumfriesshire; Eastwood and Edinburgh Central, where party leader Ruth Davidson stood for election. This marked the party's best electoral performance in Scotland since the 1992 UK general election.

2017 UK general election

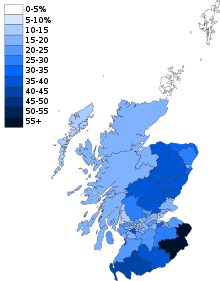

_-_Conservative_vote_share.svg.png)

Campaigning in opposition to proposals put forward by Nicola Sturgeon and the Scottish Parliament for a second referendum on Scottish independence to be held following the United Kingdom's decision to leave the European Union in a referendum held in 2016 which was not supported by a majority of Scottish voters, the Scottish Conservatives had their best ever election in Scotland in seat terms since 1983 at the 2017 general election. The Conservatives gained 12 MP's in Scotland to give them 13 in total. The party had their largest vote share in a general election in Scotland since 1979, taking a total of 757,949 votes (28.6%) in Scotland.

David Mundell held on to his Dumfrieesshire, Clydesdale and Tweeddale seat with an increased majority of 9,441 votes (19.3%). The party also gained the Ayr, Carrick and Cumnock; Berwickshire, Roxburgh and Selkirk; and Dumfries and Galloway constituencies to the south of the country, and gained East Renfrewshire on the outskirts of Glasgow.

The Conservatives also took a majority of seats in the North East of Scotland, gaining former First Minister of Scotland Alex Salmond's Gordon constituency, alongside Moray, the seat of the SNP's Westminster leader Angus Robertson. Other gains for the party in the North East included Aberdeen South; Angus; Banff and Buchan; and West Aberdeenshire and Kincardine. The party took the Ochil and South Perthshire; and Stirling constituencies in central Scotland and missed out to the SNP in Perth and North Perthshire by just 21 votes.

Policies

The Scottish Conservatives are a centre-right political party, with a commitment to Scotland remaining a part of the United Kingdom. It is autonomous from the Conservative Party across the UK in the creation of policy in devolved areas. In August 2006, the-then Leader of the Conservative Party, David Cameron, said that the party should recognise "that the policies of Conservatives in Scotland and Wales will not always be the same as our policies in England" and that the "West Lothian question must be answered from a Unionist perspective".[19]

In certain areas, the party has adopted different policy positions from the UK Conservatives. Following the Sutherland Report in 1999, the party voted with the Scottish Executive in 2002 to introduce free personal care for the elderly funded from general taxation.

Party organisation

The party is governed by a Party Management Board convened the Party Chairman, currently Robert Forman. The Management Board also consists of the party leader, conference convener, secretary, treasurer and three regional conveners representing the north, east and west of Scotland areas. As of June 2016, these are-

- Robert Forman, Chairman of the Scottish Conservatives

- Ruth Davidson MSP, Leader of the Scottish Conservatives

- Richard Wilkinson, Conference Convener

- Leonard Wallace, Honorary Secretary

- Bryan Johnston, Treasurer

- Charles Kennedy, East of Scotland Regional Convener

- George Carr, North of Scotland Regional Convener

- Gordon Wallace-Brown, West of Scotland Regional Convener

The party leader is elected by members on a one-member-one-vote basis, with the chairman appointed by the Scottish leader after consultation with the UK party leader. The Conference convener is a voluntary officer elected by members at the party's annual conference who must have been a former regional convener, and is responsible for chairing the conference and the party's convention.[20]

Leader of the Party

The position of leader of the Scottish Conservatives was created in 2011. Between 1999 and 2011, the position listed below was leader of the Scottish Conservatives in the Scottish Parliament. The new position of Scottish party leader was created following the recommendations of the Sanderson Commission.[21]

| No. | Image | Name | Term start | Term end |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | David McLetchie | 6 May 1999 | 31 October 2005 | |

| 2 | Annabel Goldie | 31 October 2005 | 4 November 2011 | |

| 3 |  | Ruth Davidson | 4 November 2011 | Incumbent |

Central staff

The party's registered headquarters is at Scottish Conservative Central Office (SCCO), 67 Northumberland Street, Edinburgh. Between 2001 and 2010, SCCO was housed in an office on Princes Street.[22]

The party's central staff is headed by the Director of the Party, currently the Lord McInnes of Kilwinning, who serves as its chief executive. There are also three campaign managers appointed to three defined regions of Scotland.

Scottish Parliament spokespeople

The front bench formulates the party's policy on issues devolved to the Scottish Parliament.

| Member of the Scottish Parliament | Constituency or Region | First elected | Current Role[23] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ruth Davidson | Edinburgh Central | 2011 | Leader of the Scottish Conservative Party |

| Jackson Carlaw | Eastwood | 2007 | Deputy Leader and shadow cabinet secretary for Europe and external affairs |

| Maurice Golden | West Scotland | 2016 | Chief Whip & Business Manager, spokesperson for the low carbon economy |

| Murdo Fraser | Mid Scotland and Fife | 2001 | Shadow cabinet secretary for finance |

| Dean Lockhart | Mid Scotland and Fife | 2016 | Shadow cabinet secretary for economy, jobs and fair work |

| Miles Briggs | Lothian | 2016 | Shadow cabinet secretary for health & sport |

| Liz Smith | Mid Scotland and Fife | 2007 | Shadow cabinet secretary for education and skills |

| Adam Tomkins | Glasgow | 2016 | Shadow cabinet secretary for communities, social security, the constitution and equalities |

| Liam Kerr | North East Scotland | 2016 | Shadow cabinet secretary for justice |

| Peter Chapman | North East Scotland | 2016 | Shadow cabinet secretary for rural economy and connectivity |

| Donald Cameron | Highlands and Islands | 2016 | Shadow cabinet secretary for the environment, climate change & land reform, 2021 policy coordinator |

| Rachael Hamilton | Ettrick, Roxburgh and Berwickshire | 2016 | Shadow cabinet secretary for culture and tourism |

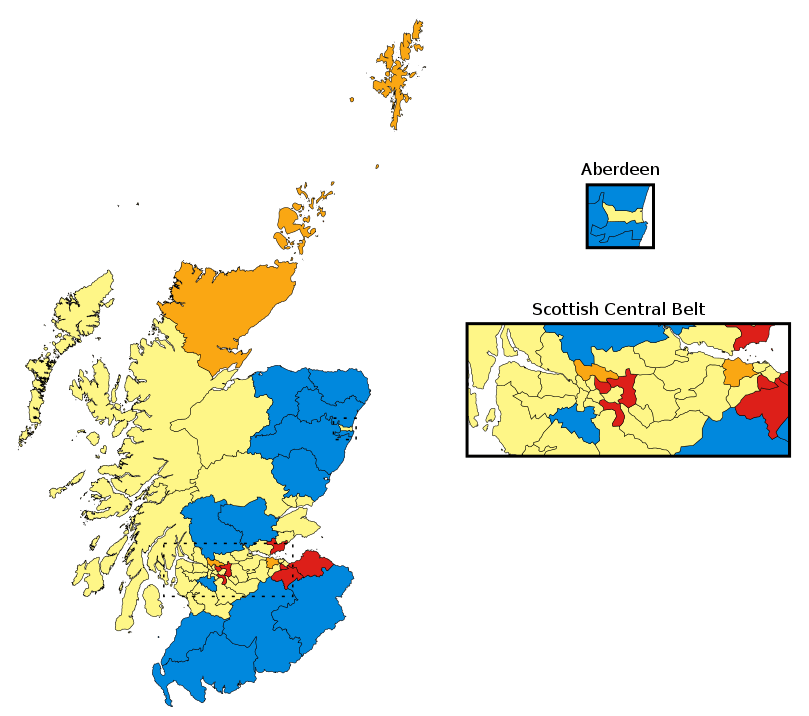

Electoral performance

In 2017, the Scottish Conservatives became the second-largest political party in Scotland in terms of democratic representation in the Scottish Parliament (following the 2016 Scottish Parliament elections), constituencies in Scotland in the UK House of Commons (following the 2017 snap election) and in local government in Scotland (following the 2017 local elections), finishing in second place behind the Scottish National Party and overtaking the Scottish Labour Party.

District Council Elections

| Year | Share of votes | Councillors |

|---|---|---|

| 1974 | 26.8% | 241 / 1,110 |

| 1977 | 27.2% | 259 / 1,107 |

| 1980 | 24.1% | 232 / 1,182 |

| 1984 | 21.4 | 189 / 1,182 |

| 1988 | 19.4 | 162 / 1,182 |

| 1992 | 23.2 | 204 / 1,158 |

Regional Council Elections

| Year | Share of votes | Councillors |

|---|---|---|

| 1974 | 28.6% | 112 / 432 |

| 1978 | 30.3% | 121 / 432 |

| 1982 | 25.1% | 119 / 441 |

| 1986 | 16.9% | 65 / 524 |

| 1990 | 19.2% | 52 / 524 |

| 1994 | 19.2% | 31 / 453 |

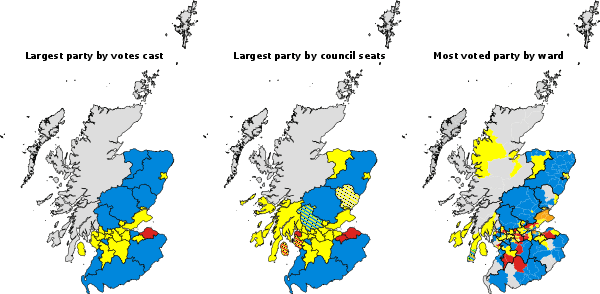

Local Council Elections

| Year | Share of votes | Councillors |

|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 11.5% | 82 / 1,155 |

| 1999 | 13.5% | 108 / 1,222 |

| 2003 | 15.1% | 122 / 1,222 |

| 2007 | 15.6% (first preference) | 143 / 1,222 |

| 2012 | 13.3% (first preference) | 115 / 1,222 |

| 2017 | 25.3% (first preference) | 276 / 1,227 |

European Parliament Elections

.svg.png)

| Year | Share of votes | Seats |

|---|---|---|

| 1979 | 33.7% | 5 / 8 |

| 1984 | 25.8% | 2 / 8 |

| 1989 | 20.9% | 0 / 8 |

| 1994 | 14.5% | 0 / 8 |

| 1999 | 19.8% | 2 / 8 |

| 2004 | 17.8% | 2 / 7 |

| 2009 | 16.8% | 1 / 6 |

| 2014 | 17.2% | 1 / 6 |

UK General Elections

| Year | Share of votes | Seats |

|---|---|---|

| 1826 | 32 / 45 | |

| 1830 | 33 / 45 | |

| 1831 | 23 / 45 | |

| 1832 | 21.0% | 10 / 53 |

| 1835 | 37.2% | 15 / 53 |

| 1837 | 46.0% | 20 / 53 |

| 1841 | 38.3% | 20 / 53 |

| 1847 | 18.3% | 20 / 53 |

| 1852 | 27.4% | 20 / 53 |

| 1857 | 15.2% | 14 / 53 |

| 1859 | 33.6% | 13 / 53 |

| 1865 | 14.6% | 11 / 53 |

| 1868 | 17.5% | 7 / 60 |

| 1874 | 31.6% | 20 / 60 |

| 1880 | 29.9% | 8 / 60 |

| 1885 | 34.3% | 10 / 72 |

| 1886 | 46.4% | 29 / 72 |

| 1892 | 44.4% | 21 / 72 |

| 1895 | 47.4% | 33 / 72 |

| 1900 | 49.0% | 38 / 72 |

| 1906 | 38.2% | 12 / 72 |

| 1910 (January) | 39.6% | 11 / 72 |

| 1910 (December) | 42.6% | 12 / 72 |

| 1918 | 32.8% | 32 / 74 |

| 1922 | 25.1% | 15 / 74 |

| 1923 | 31.6% | 16 / 74 |

| 1924 | 40.7% | 38 / 74 |

| 1929 | 35.9% | 22 / 74 |

| 1931 | 54.4% | 50 / 74 |

| 1935 | 48.7% | 35 / 72 |

| 1945 | 41.8% | 30 / 72 |

| 1950 | 44.8% | 31 / 70 |

| 1951 | 48.6% | 35 / 72 |

| 1955 | 50.1% | 36 / 72 |

| 1959 | 47.3% | 31 / 72 |

| 1964 | 40.6% | 24 / 72 |

| 1966 | 37.7% | 20 / 72 |

| 1970 | 38.0% | 23 / 72 |

| 1974 (Feb) | 32.9% | 21 / 72 |

| 1974 (Oct) | 24.7% | 16 / 72 |

| 1979 | 31.4% | 22 / 72 |

| 1983 | 28.4% | 21 / 72 |

| 1987 | 24.0% | 10 / 72 |

| 1992 | 25.8% | 11 / 72 |

| 1997 | 17.5% | 0 / 72 |

| 2001 | 15.6% | 1 / 72 |

| 2005 | 15.8% | 1 / 59 |

| 2010 | 16.7% | 1 / 59 |

| 2015 | 14.9% | 1 / 59 |

| 2017 | 28.6% | 13 / 59 |

Scottish Parliament Elections

| Year | Constituencies | Additional Member | Total seats | Change | Position | Government | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Seats | % | Seats | |||||

| 1999 | 15.6% | 0 / 73 |

15.3% | 18 / 56 |

18 / 129 |

Coalition Labour–Liberal Democrats | ||

| 2003 | 16.6% | 3 / 73 |

15.5% | 15 / 56 |

18 / 129 |

Coalition Labour–Liberal Democrats | ||

| 2007 | 16.6% | 4 / 73 |

13.9% | 13 / 56 |

17 / 129 |

Minority Scottish National Party | ||

| 2011 | 13.9% | 3 / 73 |

12.4% | 12 / 56 |

15 / 129 |

Scottish National Party | ||

| 2016 | 22.0% | 7 / 73 |

22.9% | 24 / 56 |

31 / 129 |

Minority Scottish National Party | ||

See also

References

- ↑ Ruth Davidson, 2012 Scottish Conservative Conference Address

- 1 2 Nordsieck, Wolfram (2016). "Scotland/UK". Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ↑ Ibpus.com; International Business Publications, USA (1 January 2012). Scotland Business Law Handbook: Strategic Information and Laws. Int'l Business Publications. pp. 29–. ISBN 978-1-4387-7095-6.

- ↑ Eve Hepburn (2010). Using Europe: Territorial Party Strategies in a Multi-level System. Oxford University Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-7190-8138-5.

- ↑ "Local Council Political Compositions". Open Council Date UK. 7 January 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ↑ Scottish Conservatives. "What we stand for". Scottish Conservatives. Retrieved 2017-07-11.

- ↑ "... a waning of the cultural conditions which produced the centre-right coalition that dominated Scottish politics, 1931–64, and its fragmentation into Conservatism, Liberalism, and Scottish Nationalism.", Abstract of "The Evolution of the Centre-right and the State of Scottish Conservatism", Michael Dyer, University of Aberdeen, Political Studies, Volume 49, March 2001

- ↑ James Kellas, The Scottish Political System, p. 115

- ↑ S Ball and I Holliday (eds), Catriona Burness, Mass Conservativism: The Conservatives and the Public Since the 1880s, pp.18-19

- ↑ D. Torrance, Whatever Happened to Tory Scotland, p. 3-5

- ↑ "''Scots Independent'' — Features — Scottish quotations". Scotsindependent.org. Archived from the original on 7 November 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ↑ Monteith, Brian (4 January 2015). "Brian Monteith: Time for a Unionist Party?". The Scotsman.

- ↑ BBC News (PDF) http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/shared/bsp/hi/pdfs/26_11_10_toryreport.pdf. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Garnett, Mark; Phillip Lynch (2003). The Conservatives in Crisis The Tories After 1997. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 168.

- ↑ Sunday Herald

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ↑ "Holyrood 2016: Scottish Conservative manifesto at-a-glance". BBC. 13 April 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ↑ "Budget 2016: Higher rate tax cut is 'wrong choice', says Nicola Sturgeon". BBC. 17 March 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ↑ "'Revolutionary' Cameron offers party in Scotland autonomy over policies", The Scotsman, 17 August 2006

- ↑ Sanderson Commission, p. 19

- ↑ Sanderson Commission report, p. 15

- ↑ Hello (2010-05-11). "General Election 2010: Scots Tories lose plush Capital office". The Scotsman. Retrieved 2016-07-01.

- ↑ "Ruth unveils shadow cabinet". Scottish Conservatives. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

Further reading

- The Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party: ‘the lesser spotted Tory’? (PDF file), Dr David Seawright, School of Politics and International Studies, University of Leeds, Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Political Studies Association, University of Aberdeen, 5–7 April 2002

- The Decline of the Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party 1950–1992: Religion, Ideology or Economics?, David Seawright and John Curtice, Centre for Research into Elections and Social Trends, University of Oxford, Working Paper Number 33, February 1995

- Smith, Alexander Thomas T. 2011 Devolution and the Scottish Conservatives: banal activism, electioneering and the politics of irrelevance Manchester: Manchester University Press