Unionism in Scotland

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Scotland |

|

Intergovernmental relations |

|

|

Unionism in Scotland (Scottish Gaelic: Aonachas) is a political movement, which seeks to keep Scotland within the United Kingdom (UK). Scotland is one of the countries of the United Kingdom, which has its own devolved government and Scottish Parliament, as well as representation in the UK Parliament. There are many strands of political Unionism in Scotland, some of which have ties to Unionism and Loyalism in Northern Ireland. The three main political parties in the UK, the Conservatives, Labour and Liberal Democrats, all support Scotland staying within the UK.

Scottish unionism is politically opposed to Scottish independence, which would mean Scotland leaving the UK and becoming an independent state. Political parties which support Scottish independence include: the Scottish National Party (SNP) and the Scottish Greens. The SNP have formed the devolved Scottish Government since 2007. After the SNP won an overall majority in the 2011 Scottish Parliament election, the UK and Scottish governments agreed to hold a referendum on Scottish independence, which was held in September 2014. The three main UK political parties formed the Better Together campaign, supporting Scotland remaining part of the UK. The referendum resulted in a victory for the "No" (unionist) campaign, with 55.3% of the votes cast.

Status of the term

The Conservative and Unionist Party in Scotland was called the Unionist Party before it formally merged with the Conservative Party of England and Wales in 1965, henceforth adopting the Conservative brand. Prior to the merger, the party was often known simply as the Unionists. 'Unionist' in the names of these parties is rooted in the merger of the Conservative and Liberal Unionist Parties in 1912. The union referred to therein is the 1800 Act of Union (between Great Britain and Ireland), not the Acts of Union 1707 (between England and Scotland).[1]

The term may also be used to suggest an affinity with Northern Irish unionism.

The former Secretary of State for Scotland, Michael Moore MP has written that he does not call himself a Unionist, despite being a supporter of the union. This he ascribes to the Liberal Democrat position in regard to Home Rule and decentralisation within the United Kingdom, noting that: 'for me the concept of "Unionism" does not capture the devolution journey on which we have travelled in recent years.' He suggests the connotations behind Unionism are of adherence to a constitutional status quo.[2]

History of the Union

Kingdom of Scotland

Scotland emerged as an independent polity during the Early Middle Ages, with some historians dating its foundation from the reign of Kenneth MacAlpin in 843. The independence of the Kingdom of Scotland was fought over between Scottish kings and by the Norman and Angevin rulers of England. A key period in the Kingdom of Scotland's history was a succession crisis that started in 1290, when Edward I of England claimed the Scottish throne. The resulting wars of Scottish Independence which led to Scotland securing its independent status, with Robert the Bruce (crowned in 1306) winning a major confrontation at Bannockburn in 1314.

England, Ireland and Scotland shared the same monarch in a personal union from 1603, when King James VI of Scotland also became King James I of England and Ireland, resulting in the "Union of the Crowns". A political union between the Kingdoms of Scotland, England and Ireland was temporarily formed when the crowns were overthrown as a result of the English Civil War, with Oliver Cromwell ruling over the whole of Great Britain and Ireland as Lord Protector. This period was known as the Protectorate, or to monarchists as the interregnum. The monarchies were subsequently restored in 1660, with Scotland reverting to an independent kingdom sharing the same monarch as England and Ireland.

Union between England and Scotland (1707)

The political union between the Kingdoms of Scotland and England (also including Wales) was created by the Acts of Union, passed in the parliaments of both kingdoms in 1707 and 1706 respectively. Causes for this included English fears that Scotland would select a different (Catholic) monarch in future, and the failure of the Scottish colony at Darien.

The Union was brought into existence under the Acts of Union on 1 May 1707, forming a single Kingdom of Great Britain. Scottish jacobite resistance to the union, led by descendants of James VII of Scotland (II of England), continued until 1746 and the Jacobite defeat at Culloden.

Union with Ireland (1801)

With the Acts of Union 1800, Ireland united with Great Britain into what then formed the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The history of the Unions is reflected in various stages of the Union Flag, which forms the flag of the United Kingdom. The larger part of Ireland left the United Kingdom in 1922 however Northern Ireland chose to remain within what is now called the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The 300th anniversary of the union of Scotland and England was marked in 2007.

Devolution (1999)

The Liberal Democrats, and their predecessor Liberal Party, have long been supportive of Home Rule as part of a wider belief in subsidiarity and localism.[3] In a mirror image of how the Liberal Democrat Party is itself structured, that party is generally supportive of a federal relationship between the countries of the United Kingdom.[4] The Liberal governments of the late 19th century and early 20th century supported a "home rule all round" policy,[5] which would have meant creating national parliaments in England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales, with common and external matters (such as defence and foreign affairs) decided by the UK Parliament. A "Government Of Scotland Bill" was introduced to the UK Parliament by the Liberal government in 1913, and its second reading was passed in the House of Commons by 204 votes to 159.[6] The bill did not become law, and home rule fell off the agenda after most of Ireland became independent in 1922.

Following the Kilbrandon Report in 1973, recommending a devolved Scottish Assembly, the Labour government led by Jim Callaghan introduced the Scotland Act 1978. A majority voted in favour of the proposed scheme in a March 1979 referendum on the proposal, but the Act stipulated that 40% of the total electorate had to vote in favour. The result of the referendum did not meet this additional test, and the Labour government decided not to press ahead with devolution. When the party returned to power in 1997, they introduced a second devolution referendum which resulted in the enactment of the Scotland Act 1998 and the creation of the Scottish Parliament.[7]

Unionists took different sides on the debates regarding devolution. Supporters argued that it would strengthen the Union, as giving Scotland self-government would remove the contention that independence was the only way to obtain control over internal affairs. Labour politician George Robertson said that devolution "will kill nationalism stone dead"[8] for this reason. John Smith, a Labour leader who supported devolution, believed it was the "settled will" of the Scottish people.[9] Unionist opponents of devolution argued that granting self-government would inevitably lead to the Union breaking, as they believed it would encourage nationalist sentiment and create tensions within the Union. Labour politician Tam Dalyell said devolution would be a "motorway to independence".[8] His West Lothian question asked why MPs for Scottish constituencies should be able to decide devolved matters (such as health and education) in England, but MPs for English constituencies would have no say over those matters in Scotland.[10]

The Conservatives, as a Britain-wide party, fielded candidates in Scotland until the creation of a separate Unionist Party in 1912. This was a separate party which accepted the Conservative whip in the UK Parliament until it was merged into the Conservative Party in 1965. The Declaration of Perth policy document of 1968 committed the Conservatives to Scottish devolution in some form, and in 1970 the Conservative government published Scotland's Government, a document recommending the creation of a Scottish Assembly. Support for devolution within the party was rejected and was opposed by the Conservative governments led by Margaret Thatcher and John Major in the 1980s and 1990s. The party largely remained opposed to devolution in the 1997 Scottish devolution referendum campaign.[7] That referendum was passed with a large majority, the Conservatives have since accepted devolution in both Scotland and Wales. The governments led by David Cameron devolved further powers to the Scottish Parliament in 2012 and 2016. Cameron also attempted to answer the "West Lothian question" by changing the procedures of the UK Parliament (English votes for English laws).[10]

Notable opponents of unionism are the Scottish National Party (SNP) and the Scottish Green Party.[11] The Scottish Socialist Party (SSP) and Solidarity seek to make Scotland an independent sovereign state and a republic separate from England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Of these parties, only the SNP currently has representation in the UK Parliament, which it has had continuously since winning the Hamilton by-election, 1967. The SNP and the Scottish Greens both have representation within the Scottish Parliament, with the SNP having formed the Scottish Government since 2007.

Independence referendum (2014)

The SNP won an overall majority in the 2011 Scottish Parliament election. Following that election, the UK and Scottish Governments agreed that the Scottish Parliament should be given the legal authority to hold an independence referendum by the end of 2014.[12]

The referendum was held on 18 September 2014, asking voters in Scotland the following question: "Should Scotland be an independent country?". At the poll, 2,001,926 voters (55.3%) rejected the proposal for Scotland to become an independent state over 1,617,989 (44.7%), who voted in favour of Scottish independence.[13]

The referendum result was accepted by the Scottish and British governments, leading to Scotland remaining a devolved part of the United Kingdom. Further moves have since been made towards increased devolution of power to the Scottish Parliament, which has been incorporated into UK law via the Scotland Act of 2016.

Following the referendum, the pro-independence SNP benefitted from increased membership and political support.[14] In the 2015 UK election, the SNP won 56 of the 59 seats contested in Scotland, with the three main British parties winning one seat each. The pro-unionist Scottish Conservatives then also saw increased support in the 2016 Scottish Parliament and 2017 UK general elections.

Before the latter election, the Scottish Government (formed by the SNP) had proposed a second Scottish independence referendum, due to the United Kingdom's decision to leave the European Union (EU) as following the results of a referendum held in 2016 (which the majority of voters in Scotland voted against). The SNP won 35 seats in the 2017 UK general election, a loss of 21 from the 2015 election, with their vote dropping from 50.0% in 2015 to 36.9%.

Demographics

An academic study surveying 5,000 Scots soon after the referendum in 2014 found that the No campaign performed strongest among elderly, Protestant and middle-income voters.[15] The study also found that the No campaign polled ahead among very young voters aged between 16-24, whilst the Yes campaign performed better among men, Roman Catholic voters and younger voters aged over 25 years old.[15]

According to John Curtice, polling evidence indicates that support for independence was highest among those aged in their late 20s and early 30s, with a higher No vote among those aged between 16-24.[16] There was an age gap at the referendum, with elderly voters being the most likely to vote against independence and younger voters aged under 55, with the exception of those aged between 16-24, generally being more in favour of independence.[16] Those in C2DE, or "working class", occupations were slightly more likely to vote in favour of independence than those in ABC1, or "middle class", occupations, however, there was a significant discrepancy in voting between those living in the most deprived areas and those living in the least deprived areas, with those in more deprived areas being significantly more likely to vote in favour of independence and those in more affluent areas being more likely to vote against independence.[16] This has been picked up by other academics,[17] with data from the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation study from 2012 indicating that the 6 most deprived local authorities in Scotland returned the highest Yes vote shares at the referendum.[18]

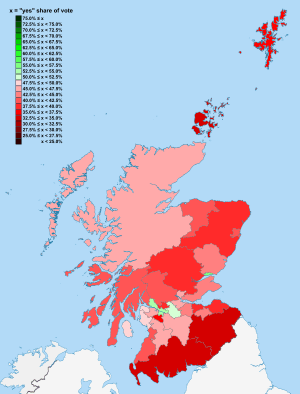

Geography

At the referendum a total of 4 out of 32 council areas voted in favour of independence, these being: North Lanarkshire (51.1% Yes), Glasgow (53.5% Yes), West Dunbartonshire (54.0% Yes) and Dundee (57.3% Yes). The largest No votes were returned by Orkney (67.2% No), Scottish Borders (66.6% No), Dumfries and Galloway (65.7% No) and Shetland (63.7% No). Generally, the Yes campaign performed strongly in deprived urban settings, such as in Greater Glasgow and Dundee, with the No campaign performing better in affluent rural and suburban areas, such as in Aberdeenshire and East Renfrewshire. The campaign saw large shifts in favour of independence in areas traditionally held by the Scottish Labour Party at the Scottish and British parliaments, with the Yes campaign performing strongly in Red Clydeside. The No campaign performed better in affluent areas traditionally held by the Scottish Liberal Democrats and Scottish Conservatives such as in East Dunbartonshire and the Scottish Borders. Surprisingly, the No campaign were able to secure a set of sizeable majorities in some council areas which have traditionally voted for the SNP, such as in Moray and Angus, where the 'No' vote was 57.6% and 56.3% respectively.

Religion

Public opinion polling conducted by Lord Ashcroft after the Scottish independence referendum found that approximately 70% of Scotland's Protestant population voted against Scottish independence over 43% of Roman Catholics, who voted majority in favour of Scottish independence.[19]

National identity

"British" national identity forms a significant part of the unionist movement in Scotland, with the vast majority of those identifying their national identity more as "British" being in favour of Scotland remaining a part of the United Kingdom, with a smaller majority of those identifying their national identity more as "Scottish" supporting Scottish independence.[20] However, many independence supporters also identify as "British" in varying degrees, with a majority of those describing their national identity as "More Scottish than British" being supportive of Scottish independence.[20]

Scottish Social Attitudes Survey

Below are findings from the Scottish Social Attitudes Survey, which is an annual survey of public opinion in Scotland from a representative sample of 1,200 - 1,500 people conducted in conjunction with organisations such as the BBC and various governmental departments, such as the Department for Communities and Local Government and the Department for Business Innovation and Skills.[21][22]

'Moreno' national identity

Respondents were asked to select the "National identity that best describes the way respondent thinks of themselves?"[23][24]

| Year | 1979 | 1992 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2003 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scottish not British | 19% | 23% | 32% | 37% | 36% | 31% | 32% | 33% | 26% | 27% | 28% | 28% | 23% | 25% | 23% |

| More Scottish than British | 40% | 38% | 35% | 31% | 30% | 34% | 32% | 32% | 29% | 31% | 30% | 32% | 30% | 29% | 26% |

| Equally Scottish and British | 33% | 27% | 22% | 21% | 24% | 22% | 21% | 21% | 27% | 26% | 26% | 23% | 30% | 29% | 32% |

| More British than Scottish | 3% | 4% | 3% | 3% | 3% | 4% | 4% | 4% | 5% | 4% | 4% | 5% | 5% | 4% | 5% |

| British not Scottish | 3% | 4% | 4% | 4% | 3% | 4% | 5% | 5% | 6% | 4% | 4% | 5% | 6% | 6% | 6% |

Forced choice

Respondents were asked to select the "National identity that best describes the way respondent thinks of themselves?"[24][25]

| Year | 1979 | 1992 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scottish | 57% | 72% | 77% | 80% | 77% | 75% | 72% | 75% | 77% | 78% | 72% | 73% | 73% | 75% | 69% | 66% | 65% |

| British | 39% | 25% | 17% | 13% | 16% | 18% | 20% | 19% | 14% | 14% | 19% | 15% | 19% | 15% | 20% | 24% | 23% |

Trends

British national identity entered a sharp decline in Scotland from 1979 until the advent of devolution in 1999, with the proportion of respondents in Scotland identifying their national identity as British falling from 39% in 1979 to just 17% in 1999, hitting an all-time-low of 13% in 2000. Since then, there has been a gradual increase in British national identity and a decline in Scottish national identity, with British national identity hitting a 20 year high in Scotland in 2013 at 24% and Scottish national identity hitting a 35-year low the following year at 65%.[24] Polling conducted since 2014 has indicated that British national identity has risen to between 31-36% in Scotland and that Scottish national identity has fallen to between 58-62%.[26]

Recent election results

UK general election, 2017

At the 2017 general election, pro-Union parties won 24 of the 59 seats in Scotland, with the SNP retaining 35 seats.[27] This represented a setback for the SNP, as they had won 56 seats in 2015.[27] Some leading SNP figures, such as Angus Robertson and former First Minister Alex Salmond, lost their seats.[27] The Scottish Conservatives won thirteen seats, which was their best result since 1983.[27] The Conservatives performed particularly strongly in the South of Scotland, as they won four seats in South Ayrshire, Dumfries and Galloway and the Borders, and in the North-east, where they won all but one of the seats available.[27] Scottish Labour and the Scottish Liberal Democrats won seven seats and four seats respectively.[28]

In terms of the share of the vote, the SNP won 36.9% of the vote, a decline of 13.1% from their performance in 2015.[28] The Conservatives came second with 28.6%, a significant increase on 2015, and Labour were third with 27.1%.[28] The combined number of votes cast for parties in support of Scottish independence at the election was 983,455 (37.12%) compared to 1,659,319 votes cast for parties in support of the union (62.62%).

Scottish Parliament election, 2016

The SNP won 63 seats of 129 available in the 2016 Scottish Parliament election. This meant that they continued in government, but no longer had an overall majority (which they had won in 2011). As the pro-independence Scottish Greens won six seats, there was still a majority of members in favour of Scottish independence. The Scottish Conservatives won 31 seats, overtaking Scottish Labour as the main opposition party in the devolved Parliament. Labour won 24 seats and finished in third place, and the Scottish Liberal Democrats won 5 seats.

Unionist parties together accounted for 1,199,045 (52.61%) constituency votes and 1,141,117 (49.92%) regional list votes, whilst nationalist parties took 1,074,097 (47.13%) constituency votes and 1,132,828 (49.56%) regional list votes.

Organisations who support the Union

Political parties

The three largest and most significant political parties that support the Union are the Labour Party, the Liberal Democrats and the Conservative and Unionist Party, all of which organise and stand in elections across Great Britain. The three parties have philosophical differences about what Scotland's status should be, particularly in their support of devolution (historically Home Rule) or federalism. These parties hold representation in both the Scottish and UK Parliaments. Other smaller political parties support the Union, including the UK Independence Party (UKIP),[29] A Better Britain – Unionist Party, Britain First,[30] Britannica Party,[31] the British National Party (BNP),[32] National Front (NF)[33] and the Scottish Unionist Party (SUP).

Other groups

The Grand Orange Lodge of Scotland also supports the continuation of the Union.[34] In March 2007, the Lodge organised a march of 12,000 of its members through Edinburgh's Royal Mile to celebrate the 300th anniversary of the Union.[35] The high turnout was believed to be in part due to opposition to Scottish independence.[36] The Orange Order used the opportunity to speak out against the possibility of nationalists increasing their share of the vote in the 2007 Scottish Parliament election. In the run up to the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, the Orange Order held a Unionist march and rally in Edinburgh which involved 15,000 Orangemen, loyalist bands and no voters from across Scotland and the UK.[37][38][39]

During the 2014 referendum campaign, a pro-Union rally by the "Let's Stay Together Campaign" was held in London's Trafalgar Square, where 5,000 people gathered to urge Scotland to vote "No" to independence.[40] Similar events were held in other cities across the rest of the United Kingdom, including in Manchester, Belfast and Cardiff.[40]

Ties to Unionism in Northern Ireland

There is some degree of social and political co-operation between some Scottish unionists and Northern Irish unionists, due to their similar aims of maintaining the unity with the United Kingdom. For example, the Orange Order parades in Orange walks in Scotland and Northern Ireland. This is largely concentrated in the Central Belt and west of Scotland. Orangeism in west and central Scotland, and opposition to it by Catholics in Scotland, can be explained as a result of the large amount of immigration from Northern Ireland.[41] A unionist rally was held in Belfast in response to the referendum on Scottish independence. Northern Irish unionists gathered to urge Scottish voters to remain within the United Kingdom.[40]

See also

References

- ↑ "Cameron plans a clever game of cat and mouse on independence – Scotsman.com News". Edinburgh: News.scotsman.com. 27 September 2008. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "Michael Moore MP writes: I am not your average unionist". Libdemvoice.org. 21 December 2011. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ↑ "Microsoft Word - Steel Commission Report March 2006 formatted.doc" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ↑ "Scottish independence: Lib Dems push federal UK plans". 17 October 2012.

- ↑ Carrell, Severin (17 October 2012). "Liberal Democrats in Scotland propose 'home rule all round'". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ↑ "GOVERNMENT OF SCOTLAND BILL". Hansard. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- 1 2 http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2009/11/26155932/3

- 1 2 Black, Andrew (26 November 2013). "Q&A: Scottish independence referendum". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ↑ "Scotland gets Smith's 'settled will'". BBC News. BBC. 12 May 1999. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- 1 2 Curran, Sean (19 September 2014). "Scottish referendum: What is the 'English Question'?". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ↑ "Scottish Green Party Manifesto 2007, pp24-25". Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ↑ Black, Andrew (15 October 2012). "Scottish independence: Cameron and Salmond strike referendum deal". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ↑ "Scotland Votes No". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ↑ "Scottish referendum: 'Yes' parties see surge in members". BBC News. BBC. 23 September 2014. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- 1 2 Fraser, Douglas (18 September 2015). "Study examines referendum demographics". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 Curtice, John (26 September 2014). "So Who Voted Yes and Who Voted No?". What Scotland Thinks. Natcen. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ↑ Mooney, Gerry (2 March 2015). "The 2014 Scottish Independence Referendum - Uneven and unequal political geographies". Open Learn. The Open University. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ↑ "High Level Summary of Statistics Trend". Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation. Scottish Government. 12 March 2013. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ↑ "How Scotland voted, and why". Lord Ashcroft. Lord Ashcroft. 19 September 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- 1 2 "Scottish Social Attitudes: From Indeyref1 to Indeyref2?, page 8" (PDF). 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ↑ "Scottish Social Attitudes". 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ↑ "Who we work for". 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ↑ "What Scotland Thinks". Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- 1 2 3 "British Social Attitudes Survey" (PDF). Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ↑ "What Scotland Thinks". Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ↑ "What Scotland Thinks". Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Carrell, Severin (11 June 2017). "Scottish Tories expected to vote as bloc to protect Scotland's interests". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- 1 2 3 Sim, Philip (12 June 2017). "Election 2017: Scotland's result in numbers". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ↑ "Scottish independence: Nigel Farage to appear at UKIP pro-Union rally". BBC News. BBC. 31 August 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ↑ Britain First official website. Statement of Principles Archived 9 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine.. "Britain First is a movement of British Unionism. We support the continued unity of the United Kingdom whilst recognising the individual identity and culture of the peoples of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. We abhor and oppose all trends that threaten the integrity of the Union". Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ↑ Beaton, Connor (21 June 2014). "BNP splinter joins anti-indy campaign". The Targe. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ↑ "Why does Scotland matter?". British National Party. 27 July 2014. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ↑ British National Front website. What we stand for. "We stand for the continuation of the UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND – Four Countries, One Nation. Scotland, Ulster, England and Wales, united under our Union Flag – we will never allow the traitors to destroy our GREAT BRITAIN!". Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ↑ "Scottish independence: Orange Lodge registers to campaign for a 'No' vote". BBC News. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ↑ "Scotland | Edinburgh and East | Orange warning over Union danger". BBC News. 24 March 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "Edinburgh Evening News". Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ Libby Brooks. "Orange Order anti-independence march a 'show of pro-union strength'". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ↑ "Orange Order descends on Edinburgh to protest against 'evil enemy' of nationalism ahead of Scottish independence vote". Mail Online. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ↑ "Orange Order march through Edinburgh to show loyalty to UK". Financial Times. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- 1 2 3 Spiro, Zachary. "'Day of Unity' grassroots rallies across the UK". Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ↑ "10-bradley-pp237-261" (PDF). Retrieved 30 April 2010.