Dune

In physical geography, a dune is a hill of loose sand built by aeolian processes (wind) or the flow of water.[1] Dunes occur in different shapes and sizes, formed by interaction with the flow of air or water. Most kinds of dunes are longer on the stoss (upflow) side, where the sand is pushed up the dune, and have a shorter "slip face" in the lee side. The valley or trough between dunes is called a slack. A "dune field" or erg is an area covered by extensive dunes.

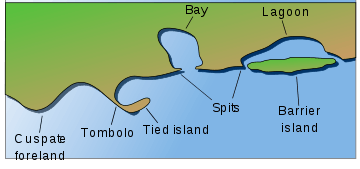

Dunes occur in some deserts and along some coasts. Some coastal areas have one or more sets of dunes running parallel to the shoreline directly inland from the beach. In most cases, the dunes are important in protecting the land against potential ravages by storm waves from the sea. Although the most widely distributed dunes are those associated with coastal regions, the largest complexes of dunes are found inland in dry regions and associated with ancient lake or sea beds. Dunes can form under the action of water flow (fluvial processes), and on sand or gravel beds of rivers, estuaries and the sea-bed.

The modern word "dune" came into English from French c. 1790,[2] which in turn came from Middle Dutch dūne.[1]

Formation

Dunes are made of sand; the sand may be quartz, calcium carbonate, snow, gypsum, or other materials. The upwind/upstream/upcurrent side of the dune is called the stoss side; the downflow side is called the lee side. Sand is pushed (creep) or bounces (saltation) up the stoss side, and slides down the lee side. A side of a dune that the sand has slid down is called a slip face.

The Bagnold formula gives the speed at which particles can be transported.

Aeolian dunes

Aeolian dune shapes

Barchan or crescentic

Barchan dunes are crescent-shaped mounds which are generally wider than they are long. The lee-side slipfaces are on the concave sides of the dunes. These dunes form under winds that blow consistently from one direction (unimodal winds). They form separate crescents when the sand supply is comparatively small. When the sand supply is greater, they may merge into barchanoid ridges, and then transverse dunes (see below).

Some types of crescentic dunes move more quickly over desert surfaces than any other type of dune. A group of dunes moved more than 100 metres per year between 1954 and 1959 in China's Ningxia Province, and similar speeds have been recorded in the Western Desert of Egypt. The largest crescentic dunes on Earth, with mean crest-to-crest widths of more than three kilometres, are in China's Taklamakan Desert.[3]

See lunettes and parabolic dues, below, for other crescent-shaped dunes.

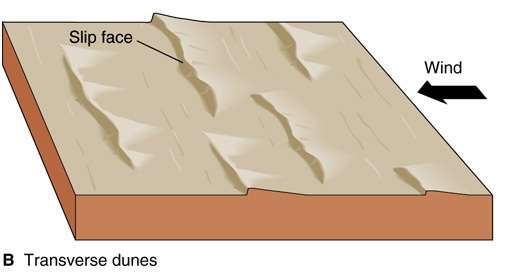

Transverse

Abundant barchan dunes (see above) may merge into barchanoid ridges, which then grade into linear (or slightly sinuous) transverse dunes, so called because they lie transverse, or across, the wind direction, with the wind blowing perpendicular to the ridge crest.[4]

Seif or longitudinal dunes

Seif dunes are linear (or slightly sinuous) dunes with two slip faces.[4] The two slip faces make them sharp-crested. They are called seif dunes after the Arabic word for "sword". They may be more than 160 kilometres (100 miles) long, and thus easily visible in satellite images (see illustrations).

Seif dunes are associated with bidirectional winds. The long axes and ridges of these dunes extend along the resultant direction of sand movement (hence the name "longitudinal").[5] Some linear dunes merge to form Y-shaped compound dunes.[6]

Formation is debated. Bagnold, in The Physics of Blown Sand and Desert Dunes, suggested that some seif dunes form when a barchan dune moves into a bidirectional wind regime, and one arm or wing of the crescent elongates. Others suggest that seif dunes are formed by vortices in a unidirectional wind.[4] In the sheltered troughs between highly developed seif dunes, barchans may be formed, because the wind is constrained to be unidirectional by the dunes.

_sand_dunes_imaged_by_Terra_(EOS_AM-1).jpg) Rub' al Khali (Arabian Empty Quarter) sand dunes imaged by Terra (EOS AM-1). Most of these dunes are seif dunes. Their origin from barchans is suggested by the stubby remnant "hooks" seen on many of the dunes. Wind would be from left to right.

Rub' al Khali (Arabian Empty Quarter) sand dunes imaged by Terra (EOS AM-1). Most of these dunes are seif dunes. Their origin from barchans is suggested by the stubby remnant "hooks" seen on many of the dunes. Wind would be from left to right. Large linear seif dunes in the Great Sand Sea in southwest Egypt, seen from the International Space Station. The distance between each dune is 1.5–2.5 km.

Large linear seif dunes in the Great Sand Sea in southwest Egypt, seen from the International Space Station. The distance between each dune is 1.5–2.5 km. The average-direction-longitudinal model of seif dune formation.

The average-direction-longitudinal model of seif dune formation. By contrast, transverse dunes form with the wind blowing perpendicular to the ridges, and have only one slipface, on the lee side. The stoss side is less steep.

By contrast, transverse dunes form with the wind blowing perpendicular to the ridges, and have only one slipface, on the lee side. The stoss side is less steep. Transverse dunes lie perpendicular to the wind, which moves them forwards, producing the cross-bedding shown here.

Transverse dunes lie perpendicular to the wind, which moves them forwards, producing the cross-bedding shown here.

Seif dunes are common in the Sahara. They range up to 300 m (980 ft) in height and 300 km (190 mi) in length. In the southern third of the Arabian Peninsula, a vast erg, called the Rub' al Khali or Empty Quarter, contains seif dunes that stretch for almost 200 km and reach heights of over 300 m.

Linear loess hills known as pahas are superficially similar. These hills appear to have been formed during the last ice age under permafrost conditions dominated by sparse tundra vegetation.

Star

Radially symmetrical, star dunes are pyramidal sand mounds with slipfaces on three or more arms that radiate from the high center of the mound. They tend to accumulate in areas with multidirectional wind regimes. Star dunes grow upward rather than laterally. They dominate the Grand Erg Oriental of the Sahara. In other deserts, they occur around the margins of the sand seas, particularly near topographic barriers. In the southeast Badain Jaran Desert of China, the star dunes are up to 500 metres tall and may be the tallest dunes on Earth.

Dome

Oval or circular mounds that generally lack a slipface. Dome dunes are rare and occur at the far upwind margins of sand seas.

Lunettes

Fixed crescentic dunes that form on the leeward margins of playas and river valleys in arid and semiarid regions in response to the direction(s) of prevailing winds, are known as lunettes, source-bordering dunes, bourrelets and clay dunes. They may be composed of clay, silt, sand, or gypsum, eroded from the basin floor or shore, transported up the concave side of the dune, and deposited on the convex side. Examples in Australia are up to 6.5 km long, 1 km wide, and up to 50 metres high. They also occur in southern and West Africa, and in parts of the western United States, especially Texas.[7]

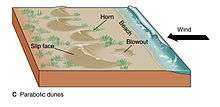

Parabolic

U-shaped mounds of sand with convex noses trailed by elongated arms are parabolic dunes. These dunes are formed from blowout dunes where the erosion of vegetated sand leads to a U-shaped depression. The elongated arms are held in place by vegetation; the largest arm known on Earth reaches 12 km. Sometimes these dunes are called U-shaped, blowout, or hairpin dunes, and they are well known in coastal deserts. Unlike crescent shaped dunes, their crests point upwind. The bulk of the sand in the dune migrates forward.

In plan view, these are U-shaped or V-shaped mounds of well-sorted, very fine to medium sand with elongated arms that extend upwind behind the central part of the dune. There are slipfaces that often occur on the outer side of the nose and on the outer slopes of the arms.

These dunes often occur in semiarid areas where the precipitation is retained in the lower parts of the dune and underlying soils. The stability of the dunes was once attributed to the vegetative cover but recent research has pointed to water as the main source of parabolic dune stability. The vegetation that covers them—grasses, shrubs, and trees—help anchor the trailing arms. In inland deserts, parabolic dunes commonly originate and extend downwind from blowouts in sand sheets only partly anchored by vegetation. They can also originate from beach sands and extend inland into vegetated areas in coastal zones and on shores of large lakes.

Most parabolic dunes do not reach heights higher than a few tens of metres except at their nose, where vegetation stops or slows the advance of accumulating sand.

Simple parabolic dunes have only one set of arms that trail upwind, behind the leading nose. Compound parabolic dunes are coalesced features with several sets of trailing arms. Complex parabolic dunes include subsidiary superposed or coalesced forms, usually of barchanoid or linear shapes.

Parabolic dunes, like crescent dunes, occur in areas where very strong winds are mostly unidirectional. Although these dunes are found in areas now characterized by variable wind speeds, the effective winds associated with the growth and migration of both the parabolic and crescent dunes probably are the most consistent in wind direction.

The grain size for these well-sorted, very fine to medium sands is about 0.06 to 0.5 mm. Parabolic dunes have loose sand and steep slopes only on their outer flanks. The inner slopes are mostly well packed and anchored by vegetation, as are the corridors between individual dunes. Because all dune arms are oriented in the same direction, and, the inter-dune corridors are generally swept clear of loose sand, the corridors can usually be traversed in between the trailing arms of the dune. However to cross straight over the dune by going over the trailing arms, can be very difficult. Also, traversing the nose is very difficult as well because the nose is usually made up of loose sand without much if any vegetation.

A type of extensive parabolic dune that lacks discernible slipfaces and has mostly coarse grained sand is known as a zibar.[8] The term zibar comes from the Arabic word to describe "rolling transverse ridges ... with a hard surface".[9] The dunes are small, have low relief, and can be found in many places across the planet from Wyoming (United States) to Saudi Arabia to Australia. Spacing between zibars ranges from 50 to 400 metres and they don't become more than 10 metres high.[10] The dunes form at about ninety degrees to the prevailing wind which blows away the small, fine-grained sand leaving behind the coarser grained sand to form the crest.[11]

Reversing dunes

Occurring wherever winds periodically reverse direction, reversing dunes are varieties of any of the above shapes. These dunes typically have major and minor slipfaces oriented in opposite directions. The minor slipfaces are usually temporary, as they appear after a reverse wind and are generally destroyed when the wind next blows in the dominant direction.[4]

Draas

Draas are very large-scale dune bedforms; they may be tens or a few hundreds of meters in height, kilometers wide, and hundreds of kilometers in length.[4] After a draa has reached a certain size, it generally develops superimposed dune forms.[12] They are thought to be more ancient and slower-moving than smaller dunes,[4] and to form by vertical growth of existing dunes. Draas are widespread in sand seas and are well-represented in the geological record.[12]

Dune complexity

All these dune shapes may occur in three forms: simple, compound, and complex. Simple dunes are basic forms with the minimum number of slipfaces that define the geometric type. Compound dunes are large dunes on which smaller dunes of similar type and slipface orientation are superimposed. Complex dunes are combinations of two or more dune types. A crescentic dune with a star dune superimposed on its crest is the most common complex dune. Simple dunes represent a wind regime that has not changed in intensity or direction since the formation of the dune, while compound and complex dunes suggest that the intensity and direction of the wind has changed.

Dune movement

The sand mass of dunes can move either windward or leeward, depending on if the wind is making contact with the dune from below or above its apogee. If wind hits from above, the sand particles move leeward. If sand hits from below, sand particles move windward. The leeward flux of sand is greater than the windward flux. Further, when the wind carrying sand particles when it hits the dune, the dune’s sand particles will saltate more than if the wind had hit the dune without carrying sand particles.[13]

Coastal dunes

Dunes form where the beach is wide enough to allow for the accumulation of wind-blown sand, and where prevailing onshore winds tend to blow sand inland. Obstacles—for example, vegetation, pebbles and so on—tend to slow down the wind and lead to the deposition of sand grains.[14] These small "incipient dunes or "shadow dunes" tend to grow in the vertical direction if the obstacle slowing the wind can also grow vertically (i.e., vegetation). Coastal dunes expand laterally as a result of lateral growth of coastal plants via seed or rhizome.[15][16] Models of coastal dunes suggest that their final equilibrium height is related to the distance between the water line and where vegetation can grow.[17] Additionally the height of coastal dunes is impacted by storm events, which can erode dunes. Recent work has suggested that coastal dunes tend to evolve toward a high or low morphology depending on the growth rate of dunes relative to storm frequency. In certain conditions, both low and high dunes are possible — dunes are a system that shows bistable dynamics.[18][19]

Dunes provide privacy and shelter from the wind.

Ecological succession on coastal dunes

As a dune forms, plant succession occurs. The conditions on an embryo dune are harsh, with salt spray from the sea carried on strong winds. The dune is well drained and often dry, and composed of calcium carbonate from seashells. Rotting seaweed, brought in by storm waves adds nutrients to allow pioneer species to colonize the dune. These pioneer species are marram grass, sea wort grass and other sea grasses in the United Kingdom. These plants are well adapted to the harsh conditions of the foredune typically having deep roots which reach the water table, root nodules that produce nitrogen compounds, and protected stoma, reducing transpiration. Also, the deep roots bind the sand together, and the dune grows into a foredune as more sand is blown over the grasses. The grasses add nitrogen to the soil, meaning other, less hardy plants can then colonize the dunes. Typically these are heather, heaths and gorses. These too are adapted to the low soil water content and have small, prickly leaves which reduce transpiration. Heather adds humus to the soil and is usually replaced by coniferous trees, which can tolerate low soil pH, caused by the accumulation and decomposition of organic matter with nitrate leaching.[20] Coniferous forests and heathland are common climax communities for sand dune systems.

Young dunes are called yellow dunes and dunes which have high humus content are called grey dunes. Leaching occurs on the dunes, washing humus into the slacks, and the slacks may be much more developed than the exposed tops of the dunes. It is usually in the slacks that more rare species are developed and there is a tendency for the dune slacks soil to be waterlogged and where only marsh plants can survive. These plants would include: creeping willow, cotton grass, yellow iris, reeds, and rushes. As for the species, there is a tendency for natterjack toads to breed here.

Coastal dune floral adaptations

Dune ecosystems are extremely difficult places for plants to survive. This is due to a number of pressures related to their proximity to the ocean and confinement to growth on sandy substrates. These include:

- Little available soil moisture

- Little available soil organic matter/nutrients

- Harsh winds

- Salt spray

- Erosion/shifting and sometimes ephemeral substrate

- Tidal influences

There are many adaptations plants have evolved to cope with these pressures:

- Deep taproot to reach water table (Pink Sand Verbena)

- Shallow but extensive root systems

- Prostrate growth form to avoid wind/salt spray (Abronia spp., Beach Primrose)

- Krummholz growth form (Monterrey Cypress-not a dune plant but deals with similar pressures)

- Thickened cuticle/Succulence to reduce moisture loss and reduce salt uptake (Ambrosia/Abronia spp., Calystegia soldanella)

- Pale leaves to reduce insolation (Artemisia/Ambrosia spp.)

- Thorny/Spiky seeds to ensure establishment in vicinity of parent, reduces chances of being blown away or swept our to sea (Ambrosia chamissonis)

Nabkha dunes

A nabkha, or coppice dune, is a small dune anchored by vegetation. They usually indicate desertification or soil erosion, and serve as nesting and burrow sites for animals.

Sub-aqueous dunes

Sub-aqueous (underwater) dunes form on a bed of sand or gravel under the actions of water flow. They are ubiquitous in natural channels such as rivers and estuaries, and also form in engineered canals and pipelines. Dunes move downstream as the upstream slope is eroded and the sediment deposited on the downstream or lee slope in typical bedform construction.[21]

These dunes most often form as a continuous 'train' of dunes, showing remarkable similarity in wavelength and height. The shape of a dune gives information about its formation environment.[22] For instance, rives produce asymmetrical ripples, with the steeper slip face facing downstream. This is useful when they are found fossilized in the geological record.

Dunes on the bed of a channel significantly increase flow resistance, their presence and growth playing a major part in river flooding.

Lithified dunes

A lithified (consolidated) sand dune is a type of sandstone that is formed when a marine or aeolian sand dune becomes compacted and hardened. Once in this form, water passing through the rock can carry and deposit minerals, which can alter the color of the rock. Cross-bedded layers of stacks of lithified dunes can produce the cross-hatching patterns, such as those seen in the Zion National Park in the western United States.

A slang term, used in the southwest US, for consolidated and hardened sand dunes is "slickrock", a name that was introduced by pioneers of the Old West because their steel-rimmed wagon wheels could not gain traction on the rock.

Desertification

Sand dunes can have a negative impact on humans when they encroach on human habitats. Sand dunes move via a few different means, all of them helped along by wind. One way that dunes can move is by saltation, where sand particles skip along the ground like a bouncing ball. When these skipping particles land, they may knock into other particles and cause them to move as well, in a process known as creep. With slightly stronger winds, particles collide in mid-air, causing sheet flows. In a major dust storm, dunes may move tens of metres through such sheet flows. Also as in the case of snow, sand avalanches, falling down the slipface of the dunes—that face away from the winds—also move the dunes forward.

Sand threatens buildings and crops in Africa, the Middle East, and China. Drenching sand dunes with oil stops their migration, but this approach is quite destructive to the dunes' animal habitats and uses a valuable resource. Sand fences might also slow their movement to a crawl, but geologists are still analyzing results for the optimum fence designs. Preventing sand dunes from overwhelming towns, villages, and agricultural areas has become a priority for the United Nations Environment Programme. Planting dunes with vegetation also helps to stabilise them.

Conservation

Dune habitats provide niches for highly specialized plants and animals, including numerous rare species and some endangered species. Due to widespread human population expansion, dunes face destruction through land development and recreational usages, as well as alteration to prevent the encroachment of sand onto inhabited areas. Some countries, notably the United States, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Netherlands, and Sri Lanka have developed significant programs of dune protection through the use of sand dune stabilization. In the U.K., a Biodiversity Action Plan has been developed to assess dunes loss and to prevent future dunes destruction.

Examples

Africa

- Alexandria Coastal Dunefields, in the Eastern Cape, South Africa[23]

- Witsand Nature Reserve in the Kalahari Desert, South Africa

- The white dunes of De Hoop Nature Reserve, South Africa

- The dunes of the Suguta Valley, a desert part of the Great Rift Valley in northwestern Kenya

- The dunes of the Danakil Depression, northeastern Ethiopia toward the border with Eritrea

- The dunes of Sossusvlei in the greater Namib-Naukluft National Park, Namibia

- The coastal dunes of Iona National Park in the southwesternmost part of Angola

- Khawa dunes in the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, the southwesternmost part of Botswana

- La Dune Rose in the city of Gao in northern Mali near the Niger River

- Erg Aoukar in southeastern Mauritania extending into Mali

- Erg Chech in southwestern Algeria and northern Mali

- Erg Chebbi and Erg Chigaga in southern Morocco

- Grand Erg Oriental in northeastern Algeria and southern Tunisia

- Grand Erg Occidental in western Algeria

- The Idehan Ubari and the Idehan Murzuq in southwestern Libya

- The Rebiana Sand Sea in southeastern Libya

- The Great Sand Sea in southeastern Libya and southwestern Egypt

- The Selima Sand Sheet in northwestern Sudan

- The dunes of the Bayuda Desert in northern Sudan

- The dunes of the Lompoul Desert in northwestern Senegal

- The coastal dunes of Bazaruto Island, Mozambique

- Erg du Djourab in northern Chad

- The dunes of the Mourdi Depression in northeastern Chad

- The dunes of Tin Toumma Desert, in southeastern Niger

- Grand Erg de Bilma in the Ténéré, in northern Niger

- The dunes of Oursi in the Sahel Region, northern Burkina Faso

- Tanzania's Shifting Sands near Olduvai Gorge

_wind_ripples.tiff.jpg)

Asia

- The dunes in the Thar Desert in India and Pakistan

- Tottori Sand Dunes, Tottori Prefecture, Japan

- Rig-e Jenn in the Central Desert of Iran.

- Rig-e Lut in the Southeast of Iran.

- The Ilocos Norte Sand Dunes in the Philippines, particularly Paoay Sand Dunes.

- Mer'eb Dune (also written as Merheb) in United Arab Emirates, used as an arena for motor sports and skiing.

- Gumuk Pasir Parangkusumo near Parangtritis beach in Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

- Mui Ne, Vietnam.

- Wahiba Sands, Oman[24]

- Teri, red dune complex in southern India

Europe

- The Dunes of Dyuni, near Pomorie, Bulgaria, vast area of sand dunes in the Burgas Province

- The Dune of Pilat, not far from Bordeaux, France, is the largest known sand dune in Europe

- The Dunes of Piscinas, in the south west of Sardinia island.

- Sands of Forvie within the Ythan Estuary complex, Aberdeenshire, Scotland.

- Oxwich Dunes, near Swansea, is on the Gower Peninsula in Wales.

- Winterton Dunes – Norfolk, England

- Słowiński National Park, Poland

- Akrotiri Sand Dune, Lemesos, Cyprus

- Råbjerg mile, Northern Jutland, Denmark

- Thy National Park, North Denmark Region, Denmark

- Dunes of Corrubedo, Spain

- Northern Littoral Natural Park, Portugal

- São Jacinto Dunes Natural Reserve, Portugal

- Rëra e Hedhur in Shëngjin, Albania

- Hoge Veluwe National Park, Veluwe, Netherlands

- Dunes of Texel National Park, Texel, Netherlands

- Zuid-Kennemerland National Park, North Holland, Netherlands

- Ammothines Lemnou, Lemnos, Greece

- Dunes of the Curonian Spit, Lithuania and Russia

North America

.jpg)

- Herring Cove[25], Race Point [26]and The Province Lands bicycle path[27] in Provincetown, Massachusetts as part of the US National Park Service of the Cape Cod National Seashore.

- Great Kobuk Sand Dunes, the northernmost sand dunes in the world, Kobuk Valley National Park, Alaska[28]

- The Athabasca Sand Dunes, located in the Athabasca Sand Dunes Provincial Park, Saskatchewan.

- The Cadiz Dunes in the Mojave Trails National Monument in California.

- The Kelso Dunes in the Mojave Desert of California.

- Eureka Valley Sand Dunes and Mesquite Flat Sand Dunes in Death Valley National Park, California.

- Great Sand Dunes National Park, Colorado.

- White Sands National Monument, New Mexico.

- Little Sahara Recreation Area, Utah.

- Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, Michigan, on the east shore of Lake Michigan.

- Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, Indiana, on the south shore of Lake Michigan.[29][30]

- Warren Dunes State Park, Michigan, on the east shore of Lake Michigan.

- Grand Sable Dunes, in the Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore, Michigan.

- Samalayuca Dunes, in the state of Chihuahua, Mexico

- Algodones Dunes near Brawley, California.

- Guadalupe-Nipomo Dunes, on the central coast of California.

- Monahans Sandhills State Park near Odessa, Texas.

- Beaver Dunes State Park near Beaver, Oklahoma.

- The Killpecker sand dunes of the Red Desert in southwestern Wyoming.

- Jockey's Ridge State Park – on the Outer Banks, North Carolina.

- The Great Dune found in Cape Henlopen State Park in Lewes, Delaware.

- Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area near Florence, Oregon, on the Pacific Coast.

- Bruneau Dunes State Park – Owyhee Desert, Idaho

- Hoffmaster State Park – Muskegon, Michigan

- Silver Lake State Park — a sand dunes that allows off-road vehicle use located in Mears, Michigan.

South America

- Lençóis Maranhenses National Park in the state of Maranhão, Brazil

- Jericoacoara National Park, in the state of Ceará, Brazil

- Genipabu in Natal, Brazil

- Medanos de Coro National Park near the town of Coro, in Falcón State, Venezuela

- Duna Federico Kirbus in Catamarca Province, Argentina

- Villa Gesell in Buenos Aires Province, Argentina

- Cerro Blanco in Nazca Province, Peru

- Huacachina in Ica Region, Peru

- Cerro Medanoso in Atacama Region, Chile

- Colún Beach, Valdivian Coastal Reserve in Chile

Oceania

- Simpson Desert sand dunes in the Northern Territory, Queensland and South Australia, Australia

- Fraser Island in Queensland, Australia

- Cronulla sand dunes in New South Wales, Australia

- Stockton Beach in New South Wales, Australia

- Te Paki sand dunes near Cape Reinga, New Zealand

World's highest dunes

| Dune | Height from Base feet/metres | Height from Sea Level feet/metres | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duna Federico Kirbus | ~4,035/1,230 | ~9,334/2,845 | Bolsón de Fiambalá, Fiambalá, Catamarca Province, Argentina | Highest in the world[31] |

| Cerro Blanco | ~3,860/1,176 | ~6,791/2,080 | Nazca Province, Ica Region, Peru 14°52′05″S 74°50′17″W / 14.868°S 74.838°W | Highest in Peru, second highest in the world |

| Badain Jaran Dunes | ~1,640/500 | ~6,640/2,020 | Badain Jaran Desert, Alashan Plain, Inner Mongolia, Gobi Desert, China | World's tallest stationary dunes and highest in Asia[32] |

| Rig-e Yalan Dune | ~1,542/470 | ~3,117/950 | Lut Desert, Kerman, Iran | Near World the hottest place (Gandom Beryan) |

| Average Highest Area Dunes | 1,410/430? | ~6,500/~1,980? | Isaouane-n-Tifernine Sand Sea, Algerian Sahara | Highest in Africa |

| Big Daddy/Dune 7 (Big Mama?)[33] |

1,256/383 | ~1,870/570 | Sossusvlei Dunes, Namib Desert, Namibia / Near Walvis Bay Namib Desert, Namibia | according to the Namibian Ministry of Environment & Tourism the highest dune in the world |

| Mount Tempest | ~920/280 | ~920/280 | Moreton Island, Brisbane, Australia | Highest in Australia |

| Star Dune | >750/230 | ~8,950/2,730 | Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve, Colorado, USA | Highest in North America |

| Dune of Pyla | ~345/105 | ~699/130 | Bay of Arcachon, Aquitaine, France | Highest in Europe |

| Ming-Sha Dunes | ? | 5,660/1,725 | Dunhuang Oasis, Taklamakan Desert, Gansu, China | |

| Medanoso Dune | ~1805/550 | ~5446/1,660 | Atacama Desert, Chile | Highest in Chile |

Sand dune systems

- (coastal dunes featuring succession)

- Athabasca Sand Dunes Provincial Park, Alberta and Saskatchewan

- Ashdod Sand Dune, Israel

- Bamburgh Dunes, Northumberland, England

- Bradley Beach, New Jersey

- Circeo National Park, a Mediterranean dune area on the southwest coast of the Lazio region of Italy

- Cronulla sand dunes, NSW, Australia

- Crymlyn Burrows, Wales

- Dawlish Warren, Devon, England

- Fraser Island, Queensland Australia, largest sand island in the world

- Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, Indiana

- Kenfig Burrows, Wales

- Margam burrows, Wales

- Murlough Sand Dunes, Newcastle, Co Down, Northern Ireland

- Morfa Harlech sand dunes, Gwynedd, Wales

- Newborough Warren, North Wales

- Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area, near North Bend, Oregon

- Penhale Sands, Cornwall, England

- Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, Michigan

- Sandy Island Beach State Park, Richland, New York

- Studland, Dorset, England

- Thy National Park, North Denmark Region, Denmark

- Winterton, Norfolk, England

- Woolacombe, Devon, England

- Ynyslas Sand Dunes, Wales

Extraterrestrial dunes

Dunes can likely be found in any environment where there is a substantial atmosphere, winds, and dust to be blown. Dunes are common on Mars and in the equatorial regions of Titan.

Titan's dunes include large expanses with modal lengths of about 20–30 km. The regions are not topographically confined, resembling sand seas. These dunes are interpreted to be longitudinal dunes whose crests are oriented parallel to the dominant wind direction, which generally indicates west-to-east wind flow. The sand is likely composed of hydrocarbon particles, possibly with some water ice mixed in.[34]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 first edited by Fowler, H.W.; Fowler, F.G. (1984). Sykes, J.B., ed. The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Current English (7th ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-861132-3.

- ↑ "Dune—Define Dune at Dictionary.com". dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 1 May 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ↑ "Types of Dunes". Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mangimeli, John (2007-09-10), Geology of Sand Dunes, U.S.A. National Park Service

- ↑ Radebaugh, Jani; Sharma, Priyanka; Korteniemi, Jarmo; Fitzsimmons, Kathryn E. (1 May 2018). Encyclopedia of Planetary Landforms. Springer, New York, NY. pp. 1–11. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-9213-9_460-2. Retrieved 1 May 2018 – via link.springer.com.

- ↑ "Types of Dunes". Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ↑ Twidale, C.R. & Campbell, E.M. (2005, revised edition): Australian landforms: understanding a low, flat, arid and old landscape. Rosenberg Publishing. Pp. 241–3. ISBN 1 877058 32 7

- ↑ Goudie, Ron Cooke; Andrew Warren; Andrew (1996). Desert geomorphology (2. impr. ed.). London: UCL Press. pp. 395–396. ISBN 1-85728-017-2.

- ↑ Goudie, Ron Cooke; Andrew Warren; Andrew (1996). Desert geomorphology (2. impr. ed.). London: UCL Press. p. 395. ISBN 1-85728-017-2.

- ↑ "USGS Landform Glossary" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- ↑ Nielsen, Ole. "Zibar Dunes". My Opera. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- 1 2 Lancaster, N. (1 March 1988). "The development of large aeolian bedforms". Sedimentary Geology. 55 (1–2): 69–89. doi:10.1016/0037-0738(88)90090-5.

- ↑ Jiang, Hong; Dun, Hongchao; Tong, Ding; Huang, Ning (2017-04-15). "Sand transportation and reverse patterns over leeward face of sand dune". Geomorphology. 283: 41–47. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2016.12.030.

- ↑ Hesp, P. (1989). "A review of biological and geomorphological processes involved in the initiation and development of incipient foredunes". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Section B. Biological Sciences. 96: 181–201. doi:10.1017/S0269727000010927.

- ↑ Godfrey, P. J. (1977-09-01). "Climate, plant response and development of dunes on barrier beaches along the U.S. east coast". International Journal of Biometeorology. 21 (3): 203–216. doi:10.1007/BF01552874. ISSN 0020-7128.

- ↑ Goldstein, Evan B.; Moore, Laura J.; Vinent, Orencio Durán (8 August 2017). "Lateral vegetation growth rates exert control on coastal foredune "hummockiness" and coalescing time". Earth Surface Dynamics. 5 (3): 417–427. doi:10.5194/esurf-5-417-2017. ISSN 2196-6311.

- ↑ Durán, O.; Moore L. J. (2013). "Vegetation controls on the maximum size of coastal dunes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (43): 17217–17222. doi:10.1073/pnas.1307580110. PMC 3808624. PMID 24101481.

- ↑ Durán, O.; Moore L. J. (2015). "Barrier island bistability induced by biophysical interactions". Nature Climate Change. 5 (2): 158–162. doi:10.1038/nclimate2474.

- ↑ Goldstein, E.B..; Moore L. J. (2016). "Vegetation controls on the maximum size of coastal dunes". Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface. 121: 964–977. doi:10.1002/2015JF003783.

- ↑ Miles, J. (1985). "The pedogenic effects of different species and vegetation types and the implications of succession". European Journal of Soil Science. 36 (4): 571. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2389.1985.tb00359.x.

- ↑ Prothero, D. R. and Schwab, F., 1996, Sedimentary Geology, pg. 45–49, ISBN 0-7167-2726-9

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 May 2018. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ↑ "Alexandria Coastal Dunefields". UNESCO World Heritage. Archived from the original on 18 November 2009. Retrieved 11 January 2010.

- ↑ Wahiba Sands

- ↑ "Herring Cove Beach - Cape Cod National Seashore (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2018-07-29.

- ↑ "Race Point Beach - Cape Cod National Seashore (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2018-07-29.

- ↑ "Province Lands Bike Trail - Cape Cod National Seashore (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2018-07-29.

- ↑ Mann, D. H.; Heiser P. A.; Finney B. P. (2002). "Holocene history of the Great Kobuk Sand Dunes, Northwestern Alaska" (PDF). Quaternary Science Reviews. Elsevier. 21 (4): 709–731. doi:10.1016/S0277-3791(01)00120-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 September 2015.

- ↑ Smith, S. & Mark, S. (2006). Alice Gray, Dorothy Buell, and Naomi Svihla: "Preservationists of Ogden Dunes". The South Shore Journal, 1. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ↑ Smith, S. & Mark, S. (2009). "The Historical Roots of the Nature Conservancy in the Northwest Indiana/Chicagoland Region: From Science to Preservation". The South Shore Journal, 3. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 2015-11-22.

- ↑ Kirbus, Federico B. "Bolsón de Fiambalá". Sandboard Magazine. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ↑ "Mystery of world's tallest sand dunes solved"—24 November 2004—New Scientist Archived 26 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Big Mama highest dune Archived 2 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Peeking Through the Haze: Titan's Surface, part II—The Planetary Society Blog | The Planetary Society Archived 28 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

References

- Bagnold, Ralph (2012) [1941]. The Physics of Blown Sand and Desert Dunes. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-14119-0.

Further reading

- Ralph Lorenz; James Zimbelman (2014). Dune Worlds: How Wind-blown Sand Shapes Planetary Landscapes. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-89724-8.

- Anthony J. Parsons, A. D. Abrahams, ed. (2009). Geomorphology of Desert Environments. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-5718-2.

- Pye, Kenneth; Tsoar, Haim (2009). Aeolian Sand and Sand Dunes. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-85909-3.

- "Nouakchott, Mauritania". NASA Earth Observatory. Archived from the original on 30 September 2006. Retrieved 28 April 2006.

- V. Badescu, R. B. Cathcart and A. A. Bolonkin, "Sand Dune Fixation: a solar-powered Sahara seawater pipeline macroproject", in: Land Degradation & Development; 19, (2008): doi:10.1002/ldr.864.

- "Types of Dunes". USGS. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- "Summary: Dunes, Parabolic". Desert Processes Working Group; Knowledge Sciences, Inc. Archived from the original on 21 October 2010. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- "Fighting wind erosion. One aspect of the combat against desertification". Les dossiers thématiques du CSFD. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 4 January 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

.jpg)