White Sands National Monument

| White Sands National Monument | |

|---|---|

|

IUCN category V (protected landscape/seascape) | |

Balloon over White Sands | |

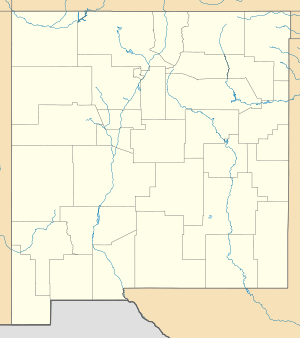

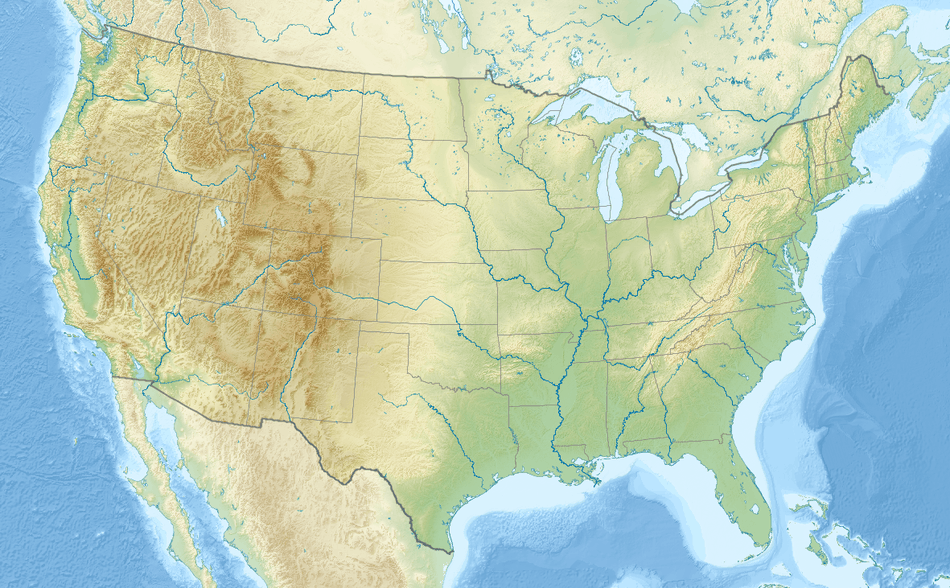

Location in New Mexico  Location in the United States | |

| Location | Otero County and Doña Ana County, New Mexico, United States |

| Nearest city | Alamogordo, New Mexico |

| Coordinates | 32°46′47″N 106°10′18″W / 32.77972°N 106.17167°WCoordinates: 32°46′47″N 106°10′18″W / 32.77972°N 106.17167°W |

| Area | 143,733 acres (224.583 sq mi; 581.67 km2)[1] |

| Established | January 18, 1933[1] |

| Visitors | 612,468[2] (in 2017) |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Official website |

|

White Sands National Monument Historic District | |

|

Visitor center | |

| Built | 1936–38 (original NRHP buildings) |

|---|---|

| Architect | Lyle E. Bennett, et al. |

| Architectural style | Pueblo Revival |

| NRHP reference # | 88000751[3] |

| NMSRCP # | 1491 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | June 23, 1988 |

| Designated NMSRCP | September 9, 1988 |

White Sands National Monument is a United States national monument located in the state of New Mexico on the north side of Route 70 about 16 miles (26 km) southwest of Alamogordo in western Otero County and northeastern Doña Ana County. The monument is situated at an elevation of 4,235 feet (1,291 m) in the mountain-ringed Tularosa Basin and comprises the southern part of a 275 sq mi (710 km2) field of white sand dunes composed of gypsum crystals. The gypsum dune field is the largest of its kind on Earth.[4]

History

The first Euro-American exploration was led by a party of US Army officers in 1849. [5]:6 [6]:5 The Mescalero Apache were already living in the area at the time. Hispanic families started farming communities in the area at Tularosa in 1861 and at La Luz in 1863.[5]:6

The idea of creating a national park to protect the white sands formation dates to 1898 when a group from El Paso proposed the creation of Mescalero National Park. The plan called for a game hunting preserve, however, which conflicted with the idea of preservation held by the Department of the Interior, and the plan failed.[5]:17[6]:52–53 In 1921–22, Albert Bacon Fall, United States Secretary of the Interior and owner of a large ranch in Three Rivers northeast of the dune field, promoted the idea of an "all-year national park" that, unlike more northerly parks, would be open even in the winter. This idea ran into a number of difficulties and did not succeed.[5]:22–25[6]:61–70 Tom Charles, an Alamogordo insurance agent and civic booster, was influenced by Fall's ideas. By emphasizing the economic benefits, Charles was able to mobilize enough support to have the national monument created.[5]:28–32[6]:77–89

National monument

On January 18, 1933, President Herbert Hoover designated White Sands National Monument, acting under the authority of the Antiquities Act of 1906.[5]:32[7] The dedication and grand opening was on April 29, 1934.[6]:102

Tom Charles became the first custodian of the monument,[5]:35[6]:99 and upon his retirement in 1939 became the first concessionaire, operating as White Sands Service Company.[5]:72[6]:117

The visitor center and a nearby comfort station, three ranger residences, as well as three maintenance buildings were constructed of adobe bricks as a Works Progress Administration project starting in 1936 and completed in 1938.[8][9] The original eight adobe buildings and other nearby structures were designated the White Sands National Monument Historic District when they were added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1988. The principal architect was Lyle E. Bennett who also designed NPS buildings at Casa Grande and Bandelier national monuments,[10] as well as Petrified Forest, Carlsbad Caverns and Mesa Verde national parks.[9]

The monument is completely surrounded by military installations (White Sands Missile Range and Holloman Air Force Base) and has always had an uneasy relationship with the military.[6]:131,175 Errant missiles often fell on the monument, in some cases destroying some of the visitor areas.[5]:145 Overflights from Holloman disturbed the tranquility of the area.[6]:149

In 1969, the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish introduced oryx into the Tularosa Basin for hunting. The oryx, having no natural predators, entered the monument and competed with native species for forage.[5]:172

In 1996, increasingly problematic alcohol abuse by students on spring break led to a ban on the consumption of alcohol, and the possession of alcohol or alcohol containers, throughout the monument from February 1 to May 31.[11][12]

World Heritage Site controversy

WSNM was placed on a tentative list of potential World Heritage Sites on January 22, 2008.[13] The state's two U.S. Senators, Pete Domenici and Jeff Bingaman, wrote letters of support of the application.[14] U.S. Representative Stevan Pearce declined to support the application, saying, "I would guarantee that if White Sands Monument receives this designation, that there will at some point be international pressures exerted that could stop military operations as we know them today."[15]

The WHS application generated much controversy in Otero County, most of it taking place in meetings of the Otero County Commission. A petition with 1,200 signatures opposing the application was presented to the commission on August 16, 2007.[16] The commission passed a resolution of opposition to the application on August 23, 2007,[17] and passed Ordinance 07-05 on October 18, 2007 relating to any potential World Heritage Site designations within the county. The ordinance requires coordination with the county in following its environmental planning and review process through its Public Land Use Advisory Council, and states that "No world heritage site...will be located on or adjacent to any military land...within or adjacent to the boundaries of Otero County."[18] On January 24, 2008, after the WHS tentative list was announced, the commission instructed the county attorney to write a letter to the Secretary of the Interior, demanding that WSNM be taken off the list.[19]

National park bill

In May 2018, U.S. Senator Martin Heinrich (Democrat–New Mexico) introduced a bill to designate White Sands a national park.[20] Heinrich consulted with monument officials, the National Park Service, White Sands Missile Range, the U.S. Army, and Holloman Air Force Base before the bill was introduced in Congress. The bill is supported by the Alamogordo City Commission, the Las Cruces City Council, the Mescalero Apache Tribal Council, the Town of Mesilla Board of Trustees, Alamogordo Mayor Richard Boss, New Mexico Senator Ron Griggs (Republican), the Alamogordo Chamber of Commerce, the Greater Las Cruces Chamber of Commerce, the Las Cruces Green Chamber of Commerce, the National Parks Conservation Association, and the Southern New Mexico Public Lands Alliance. The bill was opposed, however, by Otero County commissioners who stated that the main argument in favor of national park status was the potential for increased visitation, which they claim is uncertain, while also noting that the monument is already the most-visited NPS site in the state. The commissioners were also concerned that "the change in status will affect filmmaking here either from higher fees or increased regulation." The commissioners only supported boundary adjustments and additional infrastructure, such as campgrounds and improved road access.[21] The Doña Ana County commissioners have also opposed the redesignation of White Sands as a national park.[22]:5

Filming history

White Sands National Monument has been featured in a variety of western films, including Four Faces West (1948), Hang 'Em High (1968), The Hired Hand (1971), My Name Is Nobody (1973), Bite the Bullett (1975), and Young Guns II (1990).[23] White Sands (1992) is a crime film containing some scenes filmed in the national monument.[24] King Solomon's Mines (1950), The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), and Transformers (2007) were also filmed at White Sands.[22]:4

Description

Gypsum rarely occurs as sand because it is water-soluble. Rain usually dissolves gypsum and rivers then carry it to the sea. The Tularosa Basin has no outlet to the sea, so it traps rain that dissolves gypsum from the surrounding San Andres and Sacramento Mountains. The rainwater either sinks into the ground, or forms shallow pools that subsequently dry out and leave gypsum on the surface in a crystalline form called selenite. Groundwater that flows out of the Tularosa Basin flows south into the Hueco Basin.[25] During the last ice age, a lake now called Lake Otero covered much of the basin. When it dried out, a large flat area of selenite crystals remained, which is named the Alkali Flat. Lake Lucero, a dry lake bed which occasionally fills with water, is located in the southwest corner of the park, at one of the lowest points of the basin.

The ground in the Alkali Flat and along Lake Lucero's shore is covered with selenite crystals that measure up to three feet (1 m). Weathering and erosion eventually break the crystals into sand-size grains that are carried away by the prevailing winds from the southwest, forming the white dunes. The dunes constantly change shape and slowly move downwind. Since gypsum is water-soluble, the sand that composes the dunes may dissolve and cement together after rain, forming a layer of sand that is more solid, which increases the wind resistance of the dunes.[26] The increased resistance does not prevent dunes from quickly covering the plants in their path. Some species of plants, however, can grow fast enough to avoid being buried by the dunes.

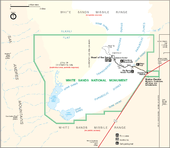

White Sands contains various forms of dunes. Dome dunes are found along the southwest margins of the field, transverse and barchan dunes in the center of the field, and parabolic dunes along the northern, southern, and northeastern margins.[27] From the visitor center at the park entrance, the Dunes Drive leads 8 miles (13 km) into the dunes. Four marked trails allow visitors to explore the dunes by foot. During the summer, there are also ranger-guided orientation and nature walks. The park participates in the Junior Ranger Program, with various age-group-specific activities.[28]

Unlike dunes made of quartz-based sand crystals, the gypsum does not readily convert the sun's energy into heat and can be walked upon safely with bare feet, even in the hottest summer months. Visitors frequently ride sleds down the dunes by the parking areas.

Both the park and U.S. Route 70 between Las Cruces and Alamogordo are subject to closure for safety reasons when tests are conducted at White Sands Missile Range which completely surrounds the monument. Tests occur about twice a week on average, for a duration of one to two hours.

Climate

| Climate data for White Sands National Monument | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 78 (26) |

85 (29) |

91 (33) |

97 (36) |

104 (40) |

111 (44) |

110 (43) |

107 (42) |

104 (40) |

97 (36) |

85 (29) |

78 (26) |

111 (44) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 57.2 (14) |

62.9 (17.2) |

70.5 (21.4) |

79.5 (26.4) |

88.1 (31.2) |

97.0 (36.1) |

97.2 (36.2) |

94.6 (34.8) |

89.0 (31.7) |

78.9 (26.1) |

66.0 (18.9) |

56.7 (13.7) |

78.1 (25.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 39.7 (4.3) |

44.3 (6.8) |

50.9 (10.5) |

59.6 (15.3) |

68.4 (20.2) |

77.8 (25.4) |

80.6 (27) |

78.2 (25.7) |

71.6 (22) |

60.0 (15.6) |

47.1 (8.4) |

39.2 (4) |

59.8 (15.4) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 22.2 (−5.4) |

25.7 (−3.5) |

31.4 (−0.3) |

39.6 (4.2) |

48.6 (9.2) |

58.6 (14.8) |

64.1 (17.8) |

61.8 (16.6) |

54.2 (12.3) |

41.1 (5.1) |

28.0 (−2.2) |

21.7 (−5.7) |

41.4 (5.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −25 (−32) |

−14 (−26) |

0 (−18) |

16 (−9) |

20 (−7) |

36 (2) |

48 (9) |

45 (7) |

34 (1) |

13 (−11) |

−12 (−24) |

−8 (−22) |

−25 (−32) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.50 (12.7) |

0.38 (9.7) |

0.28 (7.1) |

0.30 (7.6) |

0.38 (9.7) |

0.73 (18.5) |

1.35 (34.3) |

1.77 (45) |

1.29 (32.8) |

0.93 (23.6) |

0.43 (10.9) |

0.66 (16.8) |

9.01 (228.9) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.8 (2) |

0.3 (0.8) |

0.1 (0.3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.2 (0.5) |

1.0 (2.5) |

2.5 (6.4) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 42 |

| Source: Western Regional Climate Center (normals and extremes 1939-present)[29] | |||||||||||||

Gallery

Moonrise

Moonrise

Gypsum plant stand

Gypsum plant stand

Nearby cities

See also

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Otero County, New Mexico

- Trinity Site - world's first nuclear weapon test, at White Sands Missile Range

References

- 1 2 "Monument Statistics". nps.gov. National Park Service. March 20, 2017. Retrieved June 1, 2018.

- ↑ "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved 2018-06-01.

- ↑ National Park Service (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ http://www.nps.gov/whsa/naturescience/index.htm

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Welsh, Michael E. (1995). Dunes and dreams : a history of White Sands National Monument (PDF). Santa Fe, NM: Intermountain Cultural Resource Center, National Park Service. ISBN 1-58369-004-2. OCLC 54657415. Retrieved 2008-05-31.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Schneider-Hector, Dietmar (1993). White Sands: The History of a National Monument. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-1415-4. OCLC 26806926.

- ↑ "White Sands National Monument History". nps.gov. National Park Service. November 12, 2016. Retrieved June 1, 2018.

- ↑ Townsend, Dave (2007-08-26). "The New Deal and WSNM". Alamogordo Daily News. pp. 8A. OCLC 10674593.

- 1 2 "White Sands Historic District". nps.gov. National Park Service. 2017-04-07. Retrieved 2018-06-01.

- ↑ "NRHP Inventory Nomination Form: White Sands National Monument Historic District". npgallery.nps.gov. National Park Service. 1988-06-23. Retrieved 2018-06-01.

- ↑ "Monument Regulations: Alcohol Prohibition". nps.gov. National Park Service. March 20, 2017. Retrieved June 1, 2018.

- ↑ Kathy Denton (n.d.). "Alcohol Regulations: Why is alcohol banned in the monument during these times?". nps.gov. National Park Service. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved June 1, 2018.

- ↑ "Secretary Kempthorne Selects New U.S. World Heritage Tentative List" (Press release). U.S. Department of the Interior. 2008-01-22. Archived from the original on 2008-05-13. Retrieved 2008-05-23.

- ↑ "WHS Letters of Support" (PDF). U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ↑ Anderson, Karl (2007-08-17). "Steve Pearce on pause". Alamogordo Daily News. OCLC 10674593.

- ↑ Anderson, Karl (2007-08-17). "County opposes U.N. listing". Alamogordo Daily News. OCLC 10674593.

- ↑ Anderson, Karl (2007-08-24). "Anti-U.N. resolution passed". Alamogordo Daily News. OCLC 10674593.

- ↑ "Otero County, NM Code: Chapter 150 Land Development: Article V: World Heritage Sites: Ordinance No. 07-05: Applications and Designations". County of Otero. 2007-10-18. Retrieved 2018-06-01.

- ↑ Österreich, Elva K. (2008-01-25). "County issues threat to feds". Alamogordo Daily News. OCLC 10674593.

- ↑ Sen. Martin Heinrich (May 7, 2018). "S.2797 - White Sands National Park Establishment Act". congress.gov. United States Congress. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- ↑ Jacqueline Devine (May 18, 2018 ). "County opposes White Sands National Park Establishment Act". alamogordonews.com. Alamogordo Daily News. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- 1 2 Bies, Lori; Flores, Susan; White, Janet T. (May 17, 2018). "Letter from Otero County commissioners to Martin Heinrich". kob.com. Retrieved June 6, 2018. Note: PDF file linked from a KOB4 news article of May 21, 2018.

- ↑ Maddrey, Joseph (2016). The Quick, the Dead and the Revived: The Many Lives of the Western Film. McFarland. Page 182. ISBN 9781476625492.

- ↑ "White Sands (1992): Filming & Production". imdb.com. IMDb.com, Inc. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- ↑ Langford, Richard C. (2003). Tchakerian, V., ed. "The Holocene history of the White Sands dune field and influences on eolian deflation and playa lakes". Quaternary International. Oxford: Pergamon. 104: 31–39. doi:10.1016/s1040-6182(02)00133-7. ISSN 1040-6182.

- ↑ Schenk, C. J.; Fryberger, S. G. (1988-03-10). "Early diagenesis of eolian dune and interdune sands at White Sands, New Mexico". Sedimentary Geology. Amsterdam: Elsevier. 55: 109–120. doi:10.1016/0037-0738(88)90092-9. ISSN 0037-0738.

- ↑ McKee, E.D. (1966). "Structures of dunes at White Sands National Monument, New Mexico, and a comparison with structures of dunes from other selected areas". Sedimentology. 7: 3–69. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3091.1966.tb01579.x.

- ↑ "Be A Junior Ranger". nps.gov. National Park Service. August 14, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- ↑ "General Climate Summary Tables - White Sands Natl Mon, New Mexico". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to White Sands National Monument. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for White Sands National Monument. |