Symmetry

.svg.png)

Symmetry (from Greek συμμετρία symmetria "agreement in dimensions, due proportion, arrangement")[1] in everyday language refers to a sense of harmonious and beautiful proportion and balance.[2][3][lower-alpha 1] In mathematics, "symmetry" has a more precise definition, that an object is invariant to any of various transformations; including reflection, rotation or scaling. Although these two meanings of "symmetry" can sometimes be told apart, they are related, so in this article they are discussed together.

Mathematical symmetry may be observed with respect to the passage of time; as a spatial relationship; through geometric transformations; through other kinds of functional transformations; and as an aspect of abstract objects, theoretic models, language, music and even knowledge itself.[4][lower-alpha 2]

This article describes symmetry from three perspectives: in mathematics, including geometry, the most familiar type of symmetry for many people; in science and nature; and in the arts, covering architecture, art and music.

The opposite of symmetry is asymmetry.

In mathematics

In geometry

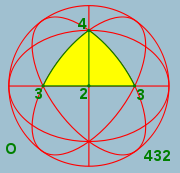

A geometric shape or object is symmetric if it can be divided into two or more identical pieces that are arranged in an organized fashion.[5] This means that an object is symmetric if there is a transformation that moves individual pieces of the object but doesn't change the overall shape. The type of symmetry is determined by the way the pieces are organized, or by the type of transformation:

- An object has reflectional symmetry (line or mirror symmetry) if there is a line going through it which divides it into two pieces which are mirror images of each other.[6]

- An object has rotational symmetry if the object can be rotated about a fixed point without changing the overall shape.[7]

- An object has translational symmetry if it can be translated without changing its overall shape.[8]

- An object has helical symmetry if it can be simultaneously translated and rotated in three-dimensional space along a line known as a screw axis.[9]

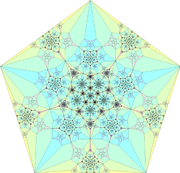

- An object has scale symmetry if it does not change shape when it is expanded or contracted.[10] Fractals also exhibit a form of scale symmetry, where small portions of the fractal are similar in shape to large portions.[11]

- Other symmetries include glide reflection symmetry and rotoreflection symmetry.

In logic

A dyadic relation R is symmetric if and only if, whenever it's true that Rab, it's true that Rba.[12] Thus, "is the same age as" is symmetrical, for if Paul is the same age as Mary, then Mary is the same age as Paul.

Symmetric binary logical connectives are and (∧, or &), or (∨, or |), biconditional (if and only if) (↔), nand (not-and, or ⊼), xor (not-biconditional, or ⊻), and nor (not-or, or ⊽).

Other areas of mathematics

Generalizing from geometrical symmetry in the previous section, we say that a mathematical object is symmetric with respect to a given mathematical operation, if, when applied to the object, this operation preserves some property of the object.[13] The set of operations that preserve a given property of the object form a group.

In general, every kind of structure in mathematics will have its own kind of symmetry. Examples include even and odd functions in calculus; the symmetric group in abstract algebra; symmetric matrices in linear algebra; and the Galois group in Galois theory. In statistics, it appears as symmetric probability distributions, and as skewness, asymmetry of distributions.[14]

In science and nature

In physics

Symmetry in physics has been generalized to mean invariance—that is, lack of change—under any kind of transformation, for example arbitrary coordinate transformations.[15] This concept has become one of the most powerful tools of theoretical physics, as it has become evident that practically all laws of nature originate in symmetries. In fact, this role inspired the Nobel laureate PW Anderson to write in his widely read 1972 article More is Different that "it is only slightly overstating the case to say that physics is the study of symmetry."[16] See Noether's theorem (which, in greatly simplified form, states that for every continuous mathematical symmetry, there is a corresponding conserved quantity such as energy or momentum; a conserved current, in Noether's original language);[17] and also, Wigner's classification, which says that the symmetries of the laws of physics determine the properties of the particles found in nature.[18]

Important symmetries in physics include continuous symmetries and discrete symmetries of spacetime; internal symmetries of particles; and supersymmetry of physical theories.

In biology

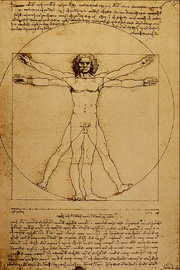

In biology, the notion of symmetry is mostly used explicitly to describe body shapes. Bilateral animals, including humans, are more or less symmetric with respect to the sagittal plane which divides the body into left and right halves.[19] Animals that move in one direction necessarily have upper and lower sides, head and tail ends, and therefore a left and a right. The head becomes specialized with a mouth and sense organs, and the body becomes bilaterally symmetric for the purpose of movement, with symmetrical pairs of muscles and skeletal elements, though internal organs often remain asymmetric.[20]

Plants and sessile (attached) animals such as sea anemones often have radial or rotational symmetry, which suits them because food or threats may arrive from any direction. Fivefold symmetry is found in the echinoderms, the group that includes starfish, sea urchins, and sea lilies.[21]

In biology, the notion of symmetry is also used as in physics, that is to say to describe the properties of the objects studied, including their interactions. A remarkable property of biological evolution is the changes of symmetry corresponding to the appearance of new parts and dynamics.[22][23]

In chemistry

Symmetry is important to chemistry because it undergirds essentially all specific interactions between molecules in nature (i.e., via the interaction of natural and human-made chiral molecules with inherently chiral biological systems). The control of the symmetry of molecules produced in modern chemical synthesis contributes to the ability of scientists to offer therapeutic interventions with minimal side effects. A rigorous understanding of symmetry explains fundamental observations in quantum chemistry, and in the applied areas of spectroscopy and crystallography. The theory and application of symmetry to these areas of physical science draws heavily on the mathematical area of group theory.[24]

In social interactions

People observe the symmetrical nature, often including asymmetrical balance, of social interactions in a variety of contexts. These include assessments of Reciprocity, empathy, sympathy, apology, dialog, respect, justice, and revenge. Reflective equilibrium is the balance that may be attained through deliberative mutual adjustment among general principles and specific judgments.[25] Symmetrical interactions send the moral message "we are all the same" while asymmetrical interactions may send the message "I am special; better than you." Peer relationships, such as can be governed by the golden rule, are based on symmetry, whereas power relationships are based on asymmetry.[26] Symmetrical relationships can to some degree be maintained by simple (game theory) strategies seen in symmetric games such as tit for tat.[27]

In the arts

In architecture

Symmetry finds its ways into architecture at every scale, from the overall external views of buildings such as Gothic cathedrals and The White House, through the layout of the individual floor plans, and down to the design of individual building elements such as tile mosaics. Islamic buildings such as the Taj Mahal and the Lotfollah mosque make elaborate use of symmetry both in their structure and in their ornamentation.[28][29] Moorish buildings like the Alhambra are ornamented with complex patterns made using translational and reflection symmetries as well as rotations.[30]

It has been said that only bad architects rely on a "symmetrical layout of blocks, masses and structures";[31] Modernist architecture, starting with International style, relies instead on "wings and balance of masses".[31]

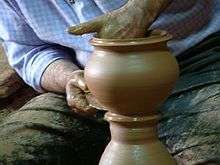

In pottery and metal vessels

Since the earliest uses of pottery wheels to help shape clay vessels, pottery has had a strong relationship to symmetry. Pottery created using a wheel acquires full rotational symmetry in its cross-section, while allowing substantial freedom of shape in the vertical direction. Upon this inherently symmetrical starting point, potters from ancient times onwards have added patterns that modify the rotational symmetry to achieve visual objectives.

Cast metal vessels lacked the inherent rotational symmetry of wheel-made pottery, but otherwise provided a similar opportunity to decorate their surfaces with patterns pleasing to those who used them. The ancient Chinese, for example, used symmetrical patterns in their bronze castings as early as the 17th century BC. Bronze vessels exhibited both a bilateral main motif and a repetitive translated border design.[32]

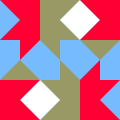

In quilts

As quilts are made from square blocks (usually 9, 16, or 25 pieces to a block) with each smaller piece usually consisting of fabric triangles, the craft lends itself readily to the application of symmetry.[33]

In carpets and rugs

A long tradition of the use of symmetry in carpet and rug patterns spans a variety of cultures. American Navajo Indians used bold diagonals and rectangular motifs. Many Oriental rugs have intricate reflected centers and borders that translate a pattern. Not surprisingly, rectangular rugs have typically the symmetries of a rectangle—that is, motifs that are reflected across both the horizontal and vertical axes (see Klein four-group § Geometry).[34][35]

In music

Symmetry is not restricted to the visual arts. Its role in the history of music touches many aspects of the creation and perception of music.

Musical form

Symmetry has been used as a formal constraint by many composers, such as the arch (swell) form (ABCBA) used by Steve Reich, Béla Bartók, and James Tenney. In classical music, Bach used the symmetry concepts of permutation and invariance.[36]

Pitch structures

Symmetry is also an important consideration in the formation of scales and chords, traditional or tonal music being made up of non-symmetrical groups of pitches, such as the diatonic scale or the major chord. Symmetrical scales or chords, such as the whole tone scale, augmented chord, or diminished seventh chord (diminished-diminished seventh), are said to lack direction or a sense of forward motion, are ambiguous as to the key or tonal center, and have a less specific diatonic functionality. However, composers such as Alban Berg, Béla Bartók, and George Perle have used axes of symmetry and/or interval cycles in an analogous way to keys or non-tonal tonal centers.[37] George Perle explains "C–E, D–F♯, [and] Eb–G, are different instances of the same interval … the other kind of identity. … has to do with axes of symmetry. C–E belongs to a family of symmetrically related dyads as follows:"[37]

| D | D♯ | E | F | F♯ | G | G♯ | ||||||

| D | C♯ | C | B | A♯ | A | G♯ |

Thus in addition to being part of the interval-4 family, C–E is also a part of the sum-4 family (with C equal to 0).[37]

| + | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||||||

| 2 | 1 | 0 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | |||||||

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

Interval cycles are symmetrical and thus non-diatonic. However, a seven pitch segment of C5 (the cycle of fifths, which are enharmonic with the cycle of fourths) will produce the diatonic major scale. Cyclic tonal progressions in the works of Romantic composers such as Gustav Mahler and Richard Wagner form a link with the cyclic pitch successions in the atonal music of Modernists such as Bartók, Alexander Scriabin, Edgard Varèse, and the Vienna school. At the same time, these progressions signal the end of tonality.[37][38]

The first extended composition consistently based on symmetrical pitch relations was probably Alban Berg's Quartet, Op. 3 (1910).[38]

Equivalency

Tone rows or pitch class sets which are invariant under retrograde are horizontally symmetrical, under inversion vertically. See also Asymmetric rhythm.

In other arts and crafts

Symmetries appear in the design of objects of all kinds. Examples include beadwork, furniture, sand paintings, knotwork, masks, and musical instruments. Symmetries are central to the art of M.C. Escher and the many applications of tessellation in art and craft forms such as wallpaper, ceramic tilework such as in Islamic geometric decoration, batik, ikat, carpet-making, and many kinds of textile and embroidery patterns.[39]

In aesthetics

The relationship of symmetry to aesthetics is complex. Humans find bilateral symmetry in faces physically attractive;[40] it indicates health and genetic fitness.[41][42] Opposed to this is the tendency for excessive symmetry to be perceived as boring or uninteresting. People prefer shapes that have some symmetry, but enough complexity to make them interesting.[43]

In literature

Symmetry can be found in various forms in literature, a simple example being the palindrome where a brief text reads the same forwards or backwards. Stories may have a symmetrical structure, as in the rise:fall pattern of Beowulf.[44]

See also

- Automorphism

- Burnside's lemma

- Chirality

- Even and odd functions

- Fixed points of isometry groups in Euclidean space – center of symmetry

- Isotropy

- Palindrome

- Spacetime symmetries

- Spontaneous symmetry breaking

- Symmetry-breaking constraints

- Symmetric relation

- Symmetries of polyiamonds

- Symmetries of polyominoes

- Symmetry group

- Wallpaper group

Notes

- ↑ For example, Aristotle ascribed spherical shape to the heavenly bodies, attributing this formally defined geometric measure of symmetry to the natural order and perfection of the cosmos.

- ↑ Symmetric objects can be material, such as a person, crystal, quilt, floor tiles, or molecule, or it can be an abstract structure such as a mathematical equation or a series of tones (music).

References

- ↑ "symmetry". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ Zee, A. (2007). Fearful Symmetry. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13482-6.

- ↑ Symmetry and the Beautiful Universe, Christopher T. Hill and Leon M. Lederman, Prometheus Books (2005)

- ↑ Mainzer, Klaus (2005). Symmetry And Complexity: The Spirit and Beauty of Nonlinear Science. World Scientific. ISBN 981-256-192-7.

- ↑ E. H. Lockwood, R. H. Macmillan, Geometric Symmetry, London: Cambridge Press, 1978

- ↑ Weyl, Hermann (1982) [1952]. Symmetry. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02374-3.

- ↑ Singer, David A. (1998). Geometry: Plane and Fancy. Springer Science & Business Media.

- ↑ Stenger, Victor J. (2000) and Mahou Shiro (2007). Timeless Reality. Prometheus Books. Especially chapter 12. Nontechnical.

- ↑ Bottema, O, and B. Roth, Theoretical Kinematics, Dover Publications (September 1990)

- ↑ Tian Yu Cao Conceptual Foundations of Quantum Field Theory Cambridge University Press p.154-155

- ↑ Gouyet, Jean-François (1996). Physics and fractal structures. Paris/New York: Masson Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-94153-0.

- ↑ Josiah Royce, Ignas K. Skrupskelis (2005) The Basic Writings of Josiah Royce: Logic, loyalty, and community (Google eBook) Fordham Univ Press, p. 790

- ↑ Christopher G. Morris (1992) Academic Press Dictionary of Science and Technology Gulf Professional Publishing

- ↑ Petitjean, M. (2003). "Chirality and Symmetry Measures: A Transdisciplinary Review". Entropy. 5 (3): 271–312 (see section 2.9). Bibcode:2003Entrp...5..271P. doi:10.3390/e5030271.

- ↑ Costa, Giovanni; Fogli, Gianluigi (2012). Symmetries and Group Theory in Particle Physics: An Introduction to Space-Time and Internal Symmetries. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 112.

- ↑ Anderson, P.W. (1972). "More is Different" (PDF). Science. 177 (4047): 393–396. Bibcode:1972Sci...177..393A. doi:10.1126/science.177.4047.393. PMID 17796623.

- ↑ Kosmann-Schwarzbach, Yvette (2010). The Noether theorems: Invariance and conservation laws in the twentieth century. Sources and Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-87867-6.

- ↑ Wigner, E. P. (1939), "On unitary representations of the inhomogeneous Lorentz group", Annals of Mathematics, 40 (1): 149–204, Bibcode:1939AnMat..40..149W, doi:10.2307/1968551, JSTOR 1968551, MR 1503456

- ↑ Valentine, James W. "Bilateria". AccessScience. Archived from the original on 18 January 2008. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ↑ Hickman, Cleveland P.; Roberts, Larry S.; Larson, Allan (2002). "Animal Diversity (Third Edition)" (PDF). Chapter 8: Acoelomate Bilateral Animals. McGraw-Hill. p. 139. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- ↑ Stewart, Ian (2001). What Shape is a Snowflake? Magical Numbers in Nature. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Longo, Giuseppe; Montévil, Maël (2016). Perspectives on Organisms: Biological time, Symmetries and Singularities. Springer. ISBN 978-3-662-51229-6.

- ↑ Montévil, Maël; Mossio, Matteo; Pocheville, Arnaud; Longo, Giuseppe (2016). "Theoretical principles for biology: Variation". Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. From the Century of the Genome to the Century of the Organism: New Theoretical Approaches. 122 (1): 36–50. doi:10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2016.08.005. PMID 27530930.

- ↑ Lowe, John P; Peterson, Kirk (2005). Quantum Chemistry (Third ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-457551-X.

- ↑ Daniels, Norman (2003-04-28). "Reflective Equilibrium". In Zalta, Edward N. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ↑ Emotional Competency: Symmetry

- ↑ Lutus, P. (2008). "The Symmetry Principle". Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ↑ Williams: Symmetry in Architecture. Members.tripod.com (1998-12-31). Retrieved on 2013-04-16.

- ↑ Aslaksen: Mathematics in Art and Architecture. Math.nus.edu.sg. Retrieved on 2013-04-16.

- ↑ Derry, Gregory N. (2002). What Science Is and How It Works. Princeton University Press. pp. 269–. ISBN 978-1-4008-2311-6.

- 1 2 Dunlap, David W. (31 July 2009). "Behind the Scenes: Edgar Martins Speaks". New York Times. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

“My starting point for this construction was a simple statement which I once read (and which does not necessarily reflect my personal views): ‘Only a bad architect relies on symmetry; instead of symmetrical layout of blocks, masses and structures, Modernist architecture relies on wings and balance of masses.’

- ↑ The Art of Chinese Bronzes Archived 2003-12-11 at the Wayback Machine.. Chinavoc (2007-11-19). Retrieved on 2013-04-16.

- ↑ Quate: Exploring Geometry Through Quilts Archived 2003-12-31 at the Wayback Machine.. Its.guilford.k12.nc.us. Retrieved on 2013-04-16.

- ↑ Marla Mallett Textiles & Tribal Oriental Rugs. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

- ↑ Dilucchio: Navajo Rugs. Navajocentral.org (2003-10-26). Retrieved on 2013-04-16.

- ↑ see ("Fugue No. 21," pdf or Shockwave)

- 1 2 3 4 Perle, George (1992). "Symmetry, the twelve-tone scale, and tonality". Contemporary Music Review. 6 (2): 81–96. doi:10.1080/07494469200640151.

- 1 2 Perle, George (1990). The Listening Composer. University of California Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-520-06991-6.

- ↑ Cucker, Felix (2013). Manifold Mirrors: The Crossing Paths of the Arts and Mathematics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 77–78, 83, 89, 103. ISBN 978-0-521-72876-8.

- ↑ Grammer, K.; Thornhill, R. (1994). "Human (Homo sapiens) facial attractiveness and sexual selection: the role of symmetry and averageness". Journal of Comparative Psychology. Washington, D.C. 108 (3): 233–42. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.108.3.233. PMID 7924253.

- ↑ Rhodes, Gillian; Zebrowitz, Leslie, A. (2002). Facial Attractiveness - Evolutionary, Cognitive, and Social Perspectives. Ablex. ISBN 1-56750-636-4.

- ↑ Jones, B. C., Little, A. C., Tiddeman, B. P., Burt, D. M., & Perrett, D. I. (2001). Facial symmetry and judgements of apparent health Support for a “‘ good genes ’” explanation of the attractiveness – symmetry relationship, 22, 417–429.

- ↑ Arnheim, Rudolf (1969). Visual Thinking. University of California Press.

- ↑ Jenny Lea Bowman (2009). "Symmetrical Aesthetics of Beowulf". University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Further reading

- The Equation That Couldn't Be Solved: How Mathematical Genius Discovered the Language of Symmetry, Mario Livio, Souvenir Press 2006, ISBN 0-285-63743-6

External links

| Look up symmetry in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Symmetry. |

- Dutch: Symmetry Around a Point in the Plane

- Chapman: Aesthetics of Symmetry

- ISIS Symmetry

- Symmetry, BBC Radio 4 discussion with Fay Dowker, Marcus du Sautoy & Ian Stewart (In Our Time, Apr. 19, 2007)

.jpg)