Tidal marsh

A tidal marsh (also known as a "tidal wetland") is a marsh found along rivers, coasts and estuaries which floods and drains by the tidal movement of the adjacent estuary, sea or ocean.[1] Tidal marshes experience many overlapping persistent cycles, including diurnal and semi-diurnal tides, day-night temperature fluctuations, spring-neap tides, seasonal vegetation growth and decay, upland runoff, decadal climate variations, and centennial to millennial trends in sea level and climate. They are also impacted by transient disturbances such as hurricanes, floods, storms, and upland fires.

Types

Tidal marshes are differentiated into freshwater, brackish and salt according to the salinity of their water. Coastal marshes lie along coasts and estuarine marshes inland within the tidal zone. Location reveals much about the origin, controlling processes, age, disturbance regime, and future of a tidal marsh. Tidal freshwater marshes are further divided into deltaic and fringing types.[2] Extensive research has been conducted on deltaic tidal freshwater marshes in Chesapeake Bay,[3] which saw many form as a result of historic deforestation and intensive agriculture.[4]

Internally, individual marshes of each salinity level are commonly zoned into lower marshes (also called intertidal marshes) and upper or high marshes, based on their elevation above sea level.[1][5] In tidal freshwater marshes there can also be a middle marsh zone.[6]

Tidal marshes may be further classified into back-barrier marshes, estuarine brackish marshes and tidal freshwater marshes, according to the degree of the influence of the sea level.[5]

Coastal

Coastal wetlands are found within coastal watersheds and encompass a variety of types including fresh and salt marshes, bottomland hardwood and mangrove swamps, and palustrine wetlands. [7] These areas provide vast benefits to the ecosystem. They serve as flood protection to upland areas by storing ground water. Additionally, shoreline erosion is impeded by the ability of wetland plants to counter wave action. Coastal wetlands act as intricate filtration systems for watersheds. [8] As water run-off travels from higher elevations to open water, the coastal wetland areas absorb and trap pollutants. These areas also provide habitat to many creatures, especially as spawning grounds and home to "feeder fish" that lie low on the food chain. They also serve as crucial rest-stops for migratory birds.

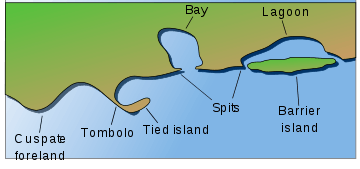

Island and barrier island

Tidal Marshes also form between a main shoreline and barrier islands. These elongate, often shifting landforms evolve parallel and close to the shoreline of a tidal marsh.[9] Many become fully submerged at high tide and exposed as directly attached to the mainland at low. Some mechanisms of barrier island formation are offshore bar theory, spit accretion theory, and climate change.[10][11] The presence of saline resistant plants does not prevent or materially impact erosion rates of tidal marsh islands, being subordinate to soil type.[12]

See also

External links

References

- 1 2 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Tidal marshes

- ↑ Pasternack, G. B. 2009. Hydrogeomorphology and sedimentation in tidal freshwater wetlands. In (A. Barendregt, A. Baldwin, P. Meire, D. Whigham, Eds) Tidal Freshwater Wetlands, Margraf Publishers GmbH, Weikersheim, Germany, p. 31-40

- ↑ "Dr. Gregory B. Pasternack - Watershed Hydrology, Geomorphology, and Ecohydraulics :: Tidal Freshwater Deltas". pasternack.ucdavis.edu. Retrieved 2017-06-11.

- ↑ Pasternack, Gregory B.; Brush, Grace S.; Hilgartner, William B. (2001-04-01). "Impact of historic land-use change on sediment delivery to a Chesapeake Bay subestuarine delta". Earth Surface Processes and Landforms. 26 (4): 409–427. doi:10.1002/esp.189. ISSN 1096-9837.

- 1 2 "Responding to Changes in Sea Level", by Marine Board, Marine Board, National Research Council (U.S.) p. 65

- ↑ Pasternack, Gregory B.; Hilgartner, William B.; Brush, Grace S. (2000-09-01). "Biogeomorphology of an upper Chesapeake Bay river-mouth tidal freshwater marsh". Wetlands. 20 (3): 520–537. doi:10.1672/0277-5212(2000)020<0520:boaucb>2.0.co;2. ISSN 0277-5212.

- ↑ EPA, OW, US. "Coastal Wetlands - US EPA". US EPA.

- ↑ Carter, V. 1997. Technical Aspects of Wetlands: Wetland Hydrology, Water Quality, and Associated Functions. United States Geological Survey Water Supply Paper 2425

- ↑ Davis, Richard A. "Barrier Island System - a Geologic Overview." Geology of Holocene Barrier Island Systems. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1994. N. pag. Print.

- ↑ Hoyt, John H (1967). "Barrier Island Formation". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 78 (9): 1125–1136. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1967)78[1125:bif]2.0.co;2.

- ↑ Kolditz, K.; Dellwig, O.; Barkowski, J.; Bahlo, R.; Leipe, T.; Freund, H.; Brumsack, H.-J. (2012). "Geochemistry of Holocene salt marsh and tidal flat sediments on a barrier island in the southern North Sea (Langeoog, North-west Germany)". Sedimentology. 59: 337–355. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3091.2011.01252.x.

- ↑ R. A. Feagin, S. M. Lozada-Bernard, T. M. Ravens, I. Möller, K. M. Yeagei, A. H. Baird