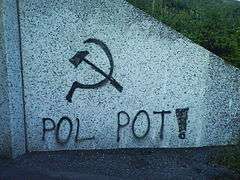

Pol Pot

| Pol Pot | |

|---|---|

| |

| General Secretary of the Communist Party of Kampuchea | |

|

In office 22 February 1963 – 6 December 1981 | |

| Deputy | Nuon Chea |

| Preceded by | Tou Samouth |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished (party dissolved) |

| Prime Minister of Democratic Kampuchea | |

|

In office 25 October 1976 – 7 January 1979 | |

| President | Khieu Samphan |

| Deputy |

Ieng Sary Son Sen Vorn Vet |

| Preceded by | Nuon Chea (acting) |

| Succeeded by | Pen Sovan |

|

In office 14 April 1976 – 27 September 1976 | |

| President | Khieu Samphan |

| Preceded by | Khieu Samphan (acting) |

| Succeeded by | Nuon Chea (acting) |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Saloth Sâr 19 May 1925[1][2] Prek Sbauv, Kampong Thom, Cambodia |

| Died |

15 April 1998 (aged 72) Anlong Veng, Oddar Meanchey, Cambodia |

| Resting place | Anlong Veng, Oddar Meanchey, Cambodia |

| Political party | Communist Party of Kampuchea |

| Spouse(s) |

Mea Son (m. 1986; his death 1998) |

| Children | Sar Patchata[3] |

| Education | EFREI |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1963–1997 |

| Rank | General |

Pol Pot (UK: /pɒl

Born to a prosperous farmer in Prek Sbauv, French Cambodia, Pol Pot was educated at some of Cambodia's elite schools. In the 1940s, Pol Pot moved to Paris, France, where he joined the French Communist Party and adopted Marxism–Leninism, particularly as it was presented in the writings of Joseph Stalin and Mao Zedong. Returning to Cambodia in 1953, he joined the Marxist–Leninist Khmer Việt Minh organisation in its guerrilla war against King Norodom Sihanouk's newly independent government. Following the Khmer Việt Minh's 1954 retreat into North Vietnam, Pol Pot returned to Phnom Penh, working as a teacher while remaining a central member of the Cambodian Marxist–Leninist movement. In 1959, he helped to convert the movement into the Kampuchean Labour Party—later renamed the Communist Party of Kampuchea—and in 1960 took control of it as party secretary. To avoid state repression, he relocated in 1962 to a Việt Cộng encampment in the jungle before visiting Hanoi and Beijing. In 1968, he re-launched the war against Sihanouk.

Renaming the country Democratic Kampuchea and seeking to create an agrarian socialist society, Pol Pot's government forcibly relocated the urban population to the countryside to work on collective farms. Those regarded as enemies of the new government were killed. These mass killings, coupled with malnutrition, strenuous working conditions, and poor medical care, killed between 1.5 to 3 million people of a population of roughly 8 million (about 25%), a period later termed the Cambodian genocide. Marxist–Leninists unhappy with Pol Pot's government encouraged Vietnamese intervention. In 1978, the Vietnamese invaded Cambodia, toppling Pol Pot's government in 1979. The Vietnamese installed a rival Marxist–Leninist faction opposed to Pol Pot and renamed the country as the People's Republic of Kampuchea. Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge retreated to a jungle base near the Thai border. Until 1993, they remained part of a coalition internationally recognized as Cambodia's rightful government. The Ta Mok faction placed Pol Pot under house arrest, where he died.

Early life

Childhood: 1925–1941

Pol Pot was born in the village of Prek Sbauv, outside the city of Kampong Thom.[5] He was given the name of Saloth Sâr, with the word sâr ("white, pale") referencing his comparatively light skin complexion.[6] Biographer Philip Short placed his birth in March 1925,[7] although an earlier biography by David P. Chandler noted that French colonial records place it on 25 May 1928.[8] His family was of mixed Chinese and ethnic Khmer heritage, although they did not speak Chinese and lived as though they were fully Khmer.[6] His father, Loth—who later took the name of Phem Saloth—was a prosperous farmer who owned nine hectares of rice land and several draft cattle.[9] Loth's house was one of the largest in the village and at transplanting and harvest time he hired poorer neighbors to carry out much of the agricultural labour.[7] Pol Pot's mother, Sok Nem, was locally respected as a pious Buddhist.[10] Pol Pot was the eighth of nine children; two were female, and seven were male.[10] Three of them died young.[11] They were raised as Theravada Buddhists, and on festivals they travelled to the Kampong Thom monastery.[12]

At the time, Cambodia was a monarchy, but the king had little political control, which was instead exercised by the French colonial regime.[13] Pol Pot's family had connections to the Cambodian royal household; his cousin Meak was a consort of the king, Sisowath Monivong, and later worked as a ballet teacher.[14] When Pol Pot was six years old, he and an older brother were sent to live with Meak in the capital city of Phnom Penh; informal adoptions by wealthier relatives was a standard practice in Cambodian society at the time.[10] In Phnom Penh, he spent several months as a novice monk in the city's Vat Botum Vaddei monastery.[15] There he became literate in the Khmer language.[16]

In the summer of 1935, Sâr went to live with his brother Suong and the latter's wife and child.[17] That year he began an education at a Roman Catholic primary school, the École Miche,[18] with Meak paying the tuition fees.[19] Most of his classmates were the children of French bureaucrats and Catholic Vietnamese.[19] He became literate in French and familiar with Christianity.[19] Sâr was not academically gifted and he was held back two years, only receiving his Certificat d'Etudes Primaires Complémentaires in 1941 when — Short argues — he was already eighteen.[20] Sâr had continued to visit Meak at the king's palace and it was there, among some of the king's concubines, that he had some of his earliest sexual experiences.[21]

Later education: 1942–1948

While Sâr was at the school, the King of Cambodia died and in 1941 the French authorities appointed Norodom Sihanouk as his replacement.[22] A new junior middle school, the Collége Pream Sihanouk, was established in Kampong Cham and Sâr was selected to become a boarder at the institution in 1942.[23] This level of education afforded him a privileged position in Cambodian society.[24] There, he learned to play the violin and took part in school plays.[25] Much of his spare time was spent playing football and basketball.[26] Several of his fellow pupils, among them Hu Nim and Khieu Samphan, later served in his government.[27] During the new year vacation in 1945, Sâr and several friends from the college theatre troupe went on a provincial tour in a bus to raise money for a trip to Angkor Wat.[28] In 1947, he left the school.[29]

That year he passed exams that admitted him into the Lycée Sisowath, meanwhile living with Suong and his new wife.[30] In the summer of 1948, he sat the brevet entry exams for the upper classes of the Lycée, but he failed. Unlike several of his friends, he could not continue on at the school for a baccalauréat.[31] Instead, he enrolled in 1948 to study carpentry at the Ecole Technique in Russey Keo, located in the northern suburbs of Phnom Pehn.[32] This drop from an academic education to a vocational one was likely a shock for the student.[33] Here, his fellow students were generally of a lower class than the students which he had encountered at his previous school, although they were not peasants.[24] It was there where he met Ieng Sary, who became a close friend and later became a fellow member of his government.[24] In the summer of 1949, Sâr passed his brevet and secured one of five scholarships allowing him to travel to France to study at one of its engineering schools.[34]

During the Second World War, France was invaded by Nazi Germany and in 1945 the Japanese ousted French control over Cambodia, with Sihanouk proclaiming independence for his country.[35] After the war ended in the defeat of Germany and Japan, France re-asserted its control over Cambodia in 1946,[36] although allowed for the creation of a new constitution and the establishment of various political parties.[37] The most successful of these was the Democratic Party, which won the 1946 general election.[38] According to Chandler, Sâr and Sary worked for the party during its successful election campaign,[39] although Short maintained that Sâr himself had no contact with the party.[33] The king opposed the party's left-leaning reforms and in 1948 dissolved the National Assembly and began ruling by decree.[40] A nascent communist movement had also been established in Cambodia by operatives of Ho Chi Minh's better established Vietnamese communist group, the Việt Minh, although it had been beset by ethnic tensions between the Khmer and Vietnamese. News of the group was censored from the press and it is unlikely Sâr was aware of them.[41]

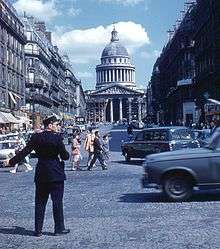

Paris: 1949–1953

Access to further education abroad marked Sâr out as part of a tiny elite in Cambodia.[42] Sâr and the 21 other selected students sailed from Saigon aboard the SS Jamalque and arrived in Marseille nearly a month later; on the journey they stopped at Singapore, Colombo, and Djibouti.[43] In Paris, Sâr enrolled at the École Française de Radioélectricité to study radio electronics.[44] He took a room in the Cité Universitaire's Indochinese Pavilion,[45] then lodgings on the rue Amyot[44] and eventually a bedsit on the corner of the rue de Commerce and the rue Letelier.[46]

He spent three years in Paris, although left on several holidays.[45] In the summer of 1950, he was one of 18 Cambodian students who joined French counterparts in traveling to Yugoslavia, a Marxist–Leninist state, to volunteer in a labour battalion building a motorway in Zagreb.[47] He returned to Yugoslavia the following year for a camping holiday.[46] In Paris, Sâr made little or no attempt to assimilate into French culture,[48] never becoming completely at ease with the French language.[44] He spent much time reading and visiting the cinema.[49] He gained a familiarity with much French literature, one of his favorite authors being Jean-Jacques Rousseau.[49] His most significant friendships in the country were with Ieng Sary, who had joined him there, Thiounn Mumm, and Keng Vannsak.[50] He was a member of Vannsak's discussion circle, whose ideologically diverse membership discussed means to achieve Cambodian independence from French rule.[51]

In Paris, Ieng Sary and two others established the Cercle Marxiste ("Marxist Circle"), a Marxist–Leninist organisation arranged in a clandestine cell system.[52] The cells met to read Marxist texts and hold self-criticism sessions.[53] Sâr joined a cell that met on the rue Lacepède; his cell comrades included Hou Yuon, Sien Ary, and Sok Knaol.[52] He helped to duplicate the Cercle's newspaper, Reaksmei ("The Spark"), named after a former Russian paper.[54] In October 1951, Yuon was elected head of the Khmer Student Association (AEK; I'Association des Estudiants Khmers), establishing close links between the organisation and the leftist Union Nationale des Étudiants de France.[55] The Cercle Marxiste manipulated the AEK and its successor organisations for the next 19 years.[52] Several months after the Cercle Marxiste's formation, Sâr and Sary joined the French Communist Party (CFP).[56] Sâr attended party meetings, including those of its Cambodian group and read its magazine, Les Cahiers Internationaux.[57] The Marxist–Leninist movement was then in a strong position globally; the Communist Party of China had recently come to power under Mao Zedong and the French Communist Party was one of the country's largest political parties,[58] attracting the votes of around 25% of the French electorate.[59]

Sâr found many of Karl Marx's denser texts difficult, later revealing that he "didn't really understand" them.[57] Instead he became familiar with the writings of the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin,[60] including Stalin's The History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks).[57] Stalin's approach to Marxism—known as Stalinism—gave Sâr a sense of purpose in life.[61] Sâr also read Mao's work, especially On New Democracy, a text outlining a Marxist–Leninist framework for carrying out a revolution in colonial and semi-colonial, semi-feudal societies.[62] Alongside these Marxist texts, Sâr read the anarchist Peter Kropotkin's book on the French Revolution of 1789, The Great Revolution.[63] From Kropotkin, he took the idea that an alliance between intellectuals and the peasantry was necessary for revolution; that a revolution needed to be carried out to its final conclusion without compromise for it to succeed; and that egalitarianism was the basis of a communist society.[64]

In Cambodia, growing internal strife resulted in King Sihanouk dismissing the government and declaring himself Prime Minister.[65] In response to Sihanouk's growing power, Saloth wrote the article "Monarchy or Democracy?"; it was published in student magazine Khmer Nisut under the pseudonym "Khmer daom" ("Original Khmer").[66] In this essay, he referred positively toward Buddhism, portraying Buddhist monks as an anti-monarchist force on the side of the peasantry.[67] At a meeting, the Cercle decided to send someone back to Cambodia to assess the situation and determine which rebel group they should support; Sâr volunteered for the role.[68] His decision to leave may also pertain to the fact that he had failed his second year exams two years in a row and had thus lost his scholarship.[69] In December, he boarded the SS Jamaique,[70] returning to Cambodia without having gained any formal degree.[71]

Revolutionary and political activism

Return to Cambodia: 1953–1954

Sâr arrived in Saigon on 13 January 1953, the same day on which Sinahouk disbanded the Democrat-controlled National Assembly, began ruling by decree and imprisoned Democratic Members of Parliament without trial.[68] Amid the broader First Indochina War in neighboring French Indochina, Cambodia was in a state of civil war,[72] with civilian massacres and other atrocities being carried out by all sides.[73] Sâr spent several months at the headquarters of Prince Norodom Chantaraingsey—the leader of one of these factions—in Trapeng Kroloeung,[74] before moving to Phnom Pehn, where he met with fellow Cercle member Ping Say to discuss the situation.[75] Sâr regarded the most promising resistance group to be the Khmer Việt Minh, a mixed Vietnamese and Cambodian guerrilla sub-group of the larger Việt Minh, the Vietnamese anti-imperialist militia organized by the Marxist-Leninist Ho Chi Minh. Sâr believed that the Khmer Việt Minh to the broader Việt Minh and thus the international Marxist–Leninist movement made it the best group for the Cercle Marxiste to support.[76] His recommendation was agreed by the Cercle members in Paris.[77]

In August 1953, Sâr and Rath Samoeun travelled to Krabao, the headquarters of the Việt Minh Eastern Zone.[78] Over the following nine months, around 12 other Cercle members joined them there.[79] They found that the Khmer Việt Minh was run by—and numerically dominated by—Vietnamese guerrillas, with Khmer recruits largely given menial tasks; Sâr was tasked with growing cassava and working in the canteen.[80] He gained a rudimentary grasp of Vietnamese,[81] and rose to become secretary and aide to Tou Samouth, the Secretary of the Khmer Việt Minh's Eastern Zone.[82]

Sihanouk desired independence from French colonial rule, but after the French government refused his requests he called for public resistance to their administration in June 1953. Khmer troops deserted the French Army in large numbers and the French government—fearing a costly and protracted war to retain colonial control—relented.[83] In October, full military powers were transferred to Sihanouk and in November he declared Cambodia an independent kingdom.[84] Post-independence, the civil conflict intensified, with France backing Sihanouk's war against the rebel groups.[85] Following the Geneva Conference held to end the First Indochina War, Sihanouk secured an agreement from the North Vietnamese that they would withdraw Khmer Việt Minh forces from Cambodian territory.[86] The final Khmer Việt Minh units left Cambodia for North Vietnam in October 1954.[87] Sâr was not among them, deciding to remain in Cambodia; he trekked, via South Vietnam, to Prey Veng to reach Phnom Penh.[88] He and other Cambodian Marxist–Leninists now decided to move on from the armed struggle and pursue their aims through electoral means.[89]

Developing the Communist Party: 1955–1962

The Cambodian Marxist-Leninists established a socialist party, Pracheachon, to serve as a front organization through which they could compete in the forthcoming 1955 election while they continued to operate clandestinely.[90] Although Pracheachon had strong support in some areas, most observers expected the Democratic Party to win.[91] The Marxist–Leninists engaged in entryism to influence Democratic policy; Vannsak had become deputy party secretary, with Sâr working as his assistant, perhaps helping to alter the party's platform.[92] Sihanouk feared a Democratic Party government and in March 1955 abdicated the throne in favor of his father, Norodom Suramarit. This allowed him to legally establish a political party, the Sangkum Reastr Niyum, with which to contest the election.[93] The September election witnessed widespread voter intimidation and electoral fraud, resulting in Sihanouk's Sangkum winning all 91 seats.[94] Sihanouk's establishment of a de facto one-party state extinguished hopes that the Cambodian Left could take power electorally.[95] The North Vietnamese government nevertheless urged the Cambodian Marxist–Leninists not to re-start the armed struggle; the former were focusing on undermining South Vietnam and had little desire to destabilize Sihanouk's regime given that it had—conveniently for them—remained internationally non-aligned rather than following the Thai and South Vietnamese governments in establishing an alliance with the anti-communist United States.[96]

Using a pseudonym, Sâr rented a house in the Boeng Keng Kang area of southern Phnom Penh.[97] Although not qualified to teach at a state school,[98] he gained employment teaching history and French literature at a private school, the Chamraon Vichea ("Progressive Knowledge");[99] his pupils, who included the later novelist Soth Polin, described him as a good teacher.[100] He courted society belle Soeung Son Maly,[101] before entering a relationship with fellow communist revolutionary Khieu Ponnary, who was the sister of Sary's wife Thirith.[102] They were married in a Buddhist ceremony in July 1956.[103]

Sâr remained deeply involved in the Cambodian left as he oversaw many of the Marxist–Leninists' underground communications while all correspondence between the Democratic Party and the Pracheachon went through him.[104] Sihanaouk had cracked down on the Marxist-Leninist movement, whose membership had halved since the end of the civil war.[105] Links with the North Vietnamese Marxist–Leninists declined, something Sâr later portrayed as a good thing.[106] He and other members increasingly regarded the Cambodians as being too subordinate to their Vietnamese counterparts; to deal with this, Sâr, Tou Samouth, and Nuon Chea drafted a programme and statutes for a new Marxist-Leninist party that would be allied, although not subordinate, to the Vietnamese.[107] They established party cells, emphasising the recruitment of small numbers of dedicated members, and organized political seminars in safe houses.[108] At a 1959 conference, the movement's leadership established the Kampuchean Labour Party, based upon the Marxist–Leninist model of democratic centralism. Sâr, Tou Samouth, and Nuon Chea were part of a four-man 'General Affair Committee' leading the party.[109] Its existence was to be kept secret from non-members.[110]

At the communist party's 1960 conference, held on the premises of a railway station, Samouth became party secretary and Nuon Chea his deputy, while Sâr took the third senior position and Ieng Sary the fourth.[111] Sihanouk vocally spoke out against the Cambodian Marxist-Leninists; although he was an ally of China's Marxist–Leninist government and admitted Marxism–Leninism's capacity to bring swift economic development and social justice, he also warned of its totalitarian character and its suppression of personal liberty.[112] In January 1962, Sihanouk's security services cracked down further on Cambodia's socialists, incarcerating the leaders of Pracheachon and leaving the party largely moribund.[113] In July, Samouth was arrested, tortured and killed.[114] Nuon Chea had also taken a step back from his political activities, leaving the way for Sâr to become party leader.[115] At the party's second conference, held in a central Phnom Penh apartment, Sâr was elected party secretary and the organisation was renamed the Kampuchean Workers' Party.[116]

As well as facing leftist opposition, Sihanouk's government also faced hostility from right-wing opposition centred upon Sihanouk's former Minister of State, Sam Sary, who was backed by the United States, Thailand and South Vietnam.[117] After the South Vietnamese supported a failed coup against Sihanouk, relations between the countries deteriorated and the United States initiated an economic blockade of Cambodia in 1956.[118] After Sihanouk's father died in 1960, Sihanouk introduced a constitutional amendment allowing himself to become head of state for life.[119] In February 1962, anti-government student protests turned into riots, at which Sihanouk dismissed the Sangkum government, called new elections, and produced a list of 34 left-leaning Cambodians, demanding that they meet him to establish a new administration.[120] Sâr was on that list—perhaps because he was known as a leftist teacher rather than because he was known as a Marxist–Leninist leader—but refused to meet with Sihanouk. He and Ieng Sary left Phnom Penh for a Viet Cong encampment near Thboung Khmum in the jungle along Cambodia's border with South Vietnam.[121] According to Chandler, "from this point on he was a full-time revolutionary".[122]

Plotting Rebellion: 1962–1968

Conditions at the Viet Cong camp were basic and food scarce.[123] As Sihanouk's government cracked down on the movement in Phnom Penh, growing numbers of its members fled to join Sâr in his jungle base.[124] In early 1964, Sâr established his own encampment, Office 100, on the South Vietnamese side of the border. Although allowing his actions to be officially separate from the Viet Cong, the latter still wielded significant control over his camp.[124] At a plenum of the party's Central Committee, it was agreed that they should re-emphasize their independence from the Vietnamese Marxist–Leninists and endorse armed struggle against Sihanouk.[124] The Central Committee met again in January 1965 to denounce the "peaceful transition" to socialism being espoused by Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, accusing him of being a revisionist.[125] In contrast to Khrushchev's interpretation of Marxism–Leninism, Sâr and his comrades sought to develop their own, explicitly Cambodian variant of the ideology.[126] Their interpretation moved away from the orthodox Marxist focus on the urban proletariat as the forces of a revolution to build socialism; instead they gave that role to the rural peasantry, who were a far larger class in Cambodian society.[127] By 1965, the party regarded Cambodia's small proletariat as being full of "enemy agents" and systematically refused them party membership.[128] Its main area of growth was in the rural provinces and by 1965 membership was at 2000.[129]

In April 1965, Sâr travelled—by foot, along the Ho Chi Minh Trail—to Hanoi to meet North Vietnamese government figures, among them Ho Chi Minh and Le Duan.[130] The North Vietnamese were preoccupied with the ongoing Vietnam War and thus did not want Sar's forces to destabilize Sihanouk's government; the latter's anti-American stance rendered him a de facto ally.[131] In Hanoi, Sâr read through the archives of the Workers' Party of Vietnam, concluding that the Vietnamese Marxist–Leninists were committed to pursuing an Indochinese Federation and that their interests were therefore incompatible with those of Cambodia.[132] From Hanoi, he flew to Beijing, where his official host was Deng Xiaoping although most of his meetings were with Peng Zhen.[133] Sâr gained a sympathetic hearing from many in the governing Communist Party of China—especially Chen Boda and Zhang Chunqiao—who shared his negative view of Khruschev amid the Sino-Soviet split.[134]

After a month in Beijing, Sâr flew back to Hanoi before a four-month journey along the Ho Chi Minh trail to reach the Cambodian Marxist–Leninists new base at Loc Ninh.[135] In October 1966, he and other Cambodian party leaders reached several key decisions. They decided to rename their organisation the Communist Party of Kampuchea, a decision initially kept secret.[136] It was agreed that they would move their headquarters in Ratanakiri Province, away from the Viet Cong, and that—despite the views of the North Vietnamese—they would command each of the party's zone committees to prepare for the re-launch of armed struggle.[137] North Vietnam refused to assist in this, rejecting their requests for weaponry.[138] In November 1967, Sâr travelled from Tay Ninh to the base Office 102 near Kang Lêng. During the journey, he fell ill with malaria and required a respite in a Viet Cong medical base near Mount Ngork.[139] By December, plans for armed conflict were complete, with the war to begin In the North-West Zone and then spread to other regions.[140] As communication across Cambodia was slow, each Zone would have to operate independently much of the time.[141]

Civil War: 1968

In January 1968, the war was launched with an attack on the Bay Damran army post south of Battambang.[141] Further attacks targeted police and soldiers and seized weaponry.[141] The government responded with scorched earth policies, aerially bombarding areas where the rebels were active.[142] Members of the Buddhist hierarchy and other establishment figures expressed concern about the brutality of government troops.[143] In some areas, troops were rewarded for each severed head they procured, resulting in them targeting civilians as well as rebels and in Phnom Penh soldiers beheaded two children using the frons of palm trees because they were accused of being rebel spies. Such reports of brutality aided the insurgents' cause.[142] As the uprising spread, over 100,000 villagers joined the rebels.[141] In the summer, Pol Pot relocated his base thirty miles north, to the more mountainous Naga's Tail, to avoid encroaching government troops.[143] In this base, called K-5, Sâr established his growing dominance over the party and had his own separate encampment, his own staff and guards and no outsider was allowed to meet him without an escort.[143] He took over from Sary as the Secretary of the North East Zone.[144] In September, Sihanouk's warm relations with China deteriorated and he instituted a marked political shift to the right, improving relations with the United States.[145]

Leadership

The movement was estimated to consist of no more than 200 regular members, but the core of the movement was supported by a number of villages many times that size. While weapons were in short supply, the insurgency still operated in twelve out of nineteen districts of Cambodia. In 1969, Sâr called a party conference and decided to change the party's propaganda strategy. Before 1969, opposition to Norodom Sihanouk was the main focus of its propaganda. However, the party decided in 1969 to shift the focus of its propaganda in order to oppose the right-wing parties of Cambodia and their alleged pro-American attitudes. While the party ceased making anti-Sihanouk statements in public, in private the party had not changed its view of him.

The road to power for Sâr and the Khmer Rouge was opened by the events of January 1970, in Cambodia. While he was out of the country, Sihanouk ordered the government to stage anti-Vietnamese protests in the capital. The protests quickly spilled out of control and the embassies of both North and South Vietnam were wrecked. Sihanouk, who had ordered the protests, then denounced them from Paris and blamed unnamed individuals in Cambodia for inciting them. These actions, along with clandestine operations by Sihanouk's followers in Cambodia, convinced the government that he should be removed as head of state. The National Assembly voted to remove Sihanouk from office and closed Cambodia's ports to North Vietnamese weapons traffic, demanding that the North Vietnamese leave Cambodia.

The North Vietnamese reacted to the political changes in Cambodia by sending Premier Phạm Văn Đồng to meet Sihanouk in China and recruit him into an alliance with the Khmer Rouge. Sâr was also contacted by the North Vietnamese, who reversed their position, offering him whatever resources he wanted for his insurgency against the Cambodian government. Sâr and Sihanouk were actually in Beijing at the same time, but the Vietnamese and Chinese leaders never informed Sihanouk of the presence of Sâr or allowed the two men to meet. Shortly afterward, Sihanouk issued an appeal by radio to the people of Cambodia asking them to rise up against the government and to support the Khmer Rouge. In May 1970, Sâr finally returned to Cambodia and the insurgency gained traction.

Earlier on 29 March 1970, the North Vietnamese had taken matters into their own hands and launched an offensive against the Cambodian army. A force of North Vietnamese quickly overran large parts of eastern Cambodia reaching to within 25 km (15 mi) of Phnom Penh before being pushed back. In these battles, the Khmer Rouge and Sâr played a very small role.

In October 1970, Sâr issued a resolution in the name of the Central Committee. The resolution stated the principle of independence-mastery (aekdreach machaskar),[146][147] which was a call for Cambodia to decide its own future independent of the influence of any other country. The resolution also included statements describing the betrayal of the Cambodian Socialist movement in the 1950s by the Viet Minh. This was the first statement of the anti-Vietnamese policy that would be a major part of the Pol Pot regime when it took power years later.

Kaing Guek Eav has claimed that American support for the Lon Nol coup contributed to the Khmer Rouge's rise to power.[148] However, diplomat Timothy M. Carney disagreed, asserting that Pol Pot won the war due to support from Sihanouk, massive supplies of military aid from North Vietnam, government corruption, the cut-off of American air support after Watergate and the determination of the Cambodian Socialists.[149]

Throughout 1971, the Vietnamese (North Vietnamese and Viet Cong) did most of the fighting against the Cambodian government while Sâr and the Khmer Rouge functioned almost as auxiliaries to their forces. Sâr took advantage of the situation in order to gather in new recruits and to train them according to a higher standard than was previously possible. Sâr also put the resources of all Khmer Rouge organizations into political education and indoctrination. While accepting anyone regardless of background into the Khmer Rouge army at this time, Sâr greatly increased the requirements for membership in the party. Students and so-called "middle peasants" were now rejected by the party. Those with clear peasant backgrounds were the preferred recruits for party membership. These restrictions were ironic in that most of the senior party leadership including Sâr came from student and middle peasant backgrounds. They also created an intellectual split between the educated old guard party members and the uneducated peasant new party members.

In early 1972, Sâr toured the insurgent/North Vietnamese controlled areas in Cambodia. He saw a regular Khmer Rouge army of 35,000 men taking shape supported by around 100,000 irregulars. China was supplying five million dollars a year in weapons and Sâr had organized an independent revenue source for the party in the form of rubber plantations in eastern Cambodia using forced labor.

After a central committee meeting in May 1972, the party under the direction of Sâr began to enforce new levels of discipline and conformity in areas under their control. Minorities such as the Chams were forced to conform to Cambodian styles of dress and appearance. These policies, such as forbidding the Chams from wearing jewelry, were soon extended to the whole population. A haphazard version of land reform was undertaken by Sâr. Its basis was that all land holdings should be of uniform size. The party also confiscated all private means of transportation. The 1972 policies were aimed at reducing the peoples of the liberated areas to a sort of feudal peasant equality. These policies were generally favorable at the time to poor peasants and were extremely unfavorable to refugees from towns, who had fled to the countryside.

In 1972, the North Vietnamese army's forces began to withdraw from the fighting against the Cambodian government. Sâr issued a new set of decrees in May 1973 that started the process of reorganizing peasant villages into cooperatives where property was jointly owned and where individual possessions were banned.

Control of the countryside

The Khmer Rouge advanced during 1973. After they reached the outskirts of Phnom Penh, Sâr issued orders that the city be taken during the peak of the rainy season. The orders led to futile attacks and wasted lives within the Khmer Rouge army. By the middle of 1973, the Khmer Rouge under Sâr controlled almost two-thirds of the country and half the population. North Vietnam realized that it no longer controlled the situation and it began to treat Sâr as more of an equal leader than as a junior partner.

In late 1973, Sâr made strategic decisions that determined the future of the war. First, he decided to cut the capital off from contact with outside sources of supplies, putting the city under siege. Second, he enforced tight control over people trying to leave the city through Khmer Rouge lines. He also ordered a series of general purges of former government officials, and anyone with an education. A set of new prisons were also constructed in Khmer Rouge run areas. The Cham minority attempted an uprising in order to stop the destruction of their culture. The uprising was quickly crushed as Sâr ordered that harsh physical torture be used against most of those involved in the revolt. As previously, Sâr tested out harsh new policies against the Cham minority before extending them to the general population of the country.

The Khmer Rouge also had a policy of evacuating urban areas and forcibly relocating their residents to the countryside. When the Khmer Rouge took the town of Kratié in 1971, Sâr and other members of the party were shocked at how fast the "liberated" urban areas shook off socialism and went back to the old ways. Various ideas were tried in order to re-create the town in the image of the party, but nothing worked. In 1973, Sâr decided out of total frustration that the only solution was to send the entire population of the town to the fields in the countryside. He wrote at the time "if the result of so many sacrifices was that the capitalists remain in control, what was the point of the revolution?". Shortly after, Sâr ordered the evacuation of the 15,000 people of Kompong Cham for the same reasons. The Khmer Rouge then moved on in 1974 to evacuate the larger city of Oudong.

Internationally, Sâr and the Khmer Rouge gained the recognition of 63 countries as the true government of Cambodia. A move was made at the UN to give the seat for Cambodia to the Khmer Rouge; they prevailed by three votes.

In September 1974, Sâr gathered the central committee of the party together. As the military campaign was moving toward a conclusion, Sâr decided to move the party toward implementing a socialist transformation of the country in the form of a series of decisions, the first being to evacuate the main cities, moving the population to the countryside. The second dictated that they would cease putting money into circulation and quickly phase it out. The final decision was that the party would accept Sâr's first major purge. In 1974, Sâr had purged a top party official named Prasith. Prasith was taken out into a forest and shot without being given any chance to defend himself. His death was followed by a purge of cadres who, like Prasith, were ethnically Thai. Sâr's explanation was that the class struggle had become acute, requiring a strong stand against party enemies.

The Khmer Rouge were positioned for a final offensive against the government in January 1975. Simultaneously, Sihanouk proudly announced at a press event in Beijing Sâr's "death list" of enemies who were to be killed after victory. The list, which originally contained seven names, was expanded to 23 and it included the names of all senior government leaders along with the names of all officials who were in positions of leadership within the police and military. The rivalry between Vietnam and Cambodia also came out into the open. North Vietnam as the rival socialist country in Indochina was determined to take Saigon before the Khmer Rouge took Phnom Penh.

In April 1975, the government formed a Supreme National Council with new leadership, with the aim of negotiating a surrender to the Khmer Rouge. It was headed by Sak Sutsakhan who had studied in France with Sâr and was a cousin of the Khmer Rouge Deputy Secretary Nuon Chea. Sâr reacted to this by adding the names of everyone involved in the Supreme National Council onto his post-victory death list. Government resistance finally collapsed on 17 April 1975.

Leader of Kampuchea

The Khmer Rouge took Phnom Penh on 17 April 1975. As the leader of the Communist Party, Sâr became the de-facto leader of the country. He adopted the title "brother number one" and used the nom de guerre Pol Pot. Philip Short offered an explanation for the origin of Pol Pot's name, stating that Sâr announced that he was adopting the name in July 1970. Short suspects that it derives from pol as "the Pols were royal slaves, an aboriginal people" and that "Pot" was simply a "euphonic monosyllable" that he liked.[150] However, the Khmer word pol is derived from Sanskrit bala ("army", "guard") and the Khmer spelling differs from the spelling of Pol Pot's name.[151] The name has no particular meaning in Khmer.[152]

Cambodia adopted a new constitution on 5 January 1976, officially changing the country's name to Democratic Kampuchea. The newly established Representative Assembly held its first plenary session from 11 to 13 April, electing a new government with Pol Pot as prime minister. His predecessor, Khieu Samphan, became head of state as President of the State Presidium. Prince Sihanouk received no role in the government and was placed in detention. The Khmer Rouge rėgime saw agriculture as the key to nation-building and national defense.[153] Pol Pot's goal for the country was to have 70–80% of the farm mechanization completed within 5 to 10 years, to build a modern industrial base on the farm mechanization within 15 to 20 years, and to become a self-sufficient state.[153] He wanted to take the economy and make it the primary source of goods for the nation, sever foreign relationships and radically reconstruct the society to maximize the production of agriculture.[154] To avoid foreign domination of industries, Pol Pot refused to purchase goods from other countries.[155]

Immediately after the fall of Phnom Penh, the Khmer Rouge began to implement their concept of Year Zero and ordered the complete evacuation of Phnom Penh and all other recently captured major towns and cities. Those leaving were told that the evacuation was due to the threat of severe American bombing and that it would last for no more than a few days. Western media depicted the events as a "death march", with American sources predicting that the Khmer Rouge policy of forced evacuation would result in famine and the mass death of hundreds of thousands.[156][157]

Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge had been evacuating captured urban areas for many years, but the evacuation of Phnom Penh was unique in its scale. Pol Pot stated that "the first step in progress [was] deliberately designed to exterminate an entire class".[158] The first operations to evacuate urban areas occurred in 1968, in the Ratanakiri area and aimed at moving people deeper into Khmer Rouge territory to control them more easily. From 1971–1973, the motivation changed. Pol Pot and the other senior leaders were frustrated that urban Cambodians retained old capitalist habits of trade and business. When all other methods had failed, the government adopted the policy of evacuation to the countryside in order to solve the "problem".

In 1976, Pol Pot's régime reclassified Kampucheans into three groupings, i.e. as full-rights (base) people, as candidates and as depositees, so called because they included most of the new people who had been deposited from the cities into the communes.[159] Depositees were marked for destruction. Their rations were reduced to two bowls of rice soup or p'baw per day, leading to widespread starvation. "New people" were allegedly given no place in the elections which took place on 20 March 1976, despite the fact that the constitution established universal suffrage for all Cambodians over the age of 18.

The Khmer Rouge leadership boasted over the state-controlled radio that only one or two million people were needed to build the new agrarian socialist utopia. As for the others, as their proverb put it: "To keep you is no benefit, to destroy you is no loss".[160]

Hundreds of thousands of the new people and later the depositees were taken out in shackles to dig their own mass graves as the Khmer Rouge soldiers buried them alive. A Khmer Rouge extermination prison directive ordered: "Bullets are not to be wasted". Such mass graves are often referred to as "the Killing Fields".

The Khmer Rouge also classified people based on their religious and ethnic backgrounds. Under the leadership of Pol Pot, the Khmer Rouge had a policy of state atheism.[161] All religions were banned, and the repression of adherents of Islam,[162] Christianity[163] and Buddhism was extensive. Nearly 25,000 Buddhist monks were massacred by the regime.[164] The regime dispersed minority groups, forbidding them to either speak their languages or practise their customs.[165] They especially targeted Muslims, Christians, Western-educated intellectuals, educated people in general, people who had contact with Western countries or Vietnam, disabled people and ethnic Chinese, Laotians and Vietnamese. Some were imprisoned in the S-21 camp for interrogation involving torture in cases where a confession was useful to the government. Many others were summarily executed.[166]

According to François Ponchaud's book Cambodia: Year Zero: "Ever since 1972, the guerrilla fighters had been sending all the inhabitants of the villages and towns they occupied into the forest to live and often burning their homes, so that they would have nothing to come back to". The Khmer Rouge systematically destroyed food sources that could not be easily subjected to centralized storage and control, cut down fruit trees, forbade fishing, outlawed the planting or harvesting of mountain leap rice, abolished medicine and hospitals, forced people to march long distances without access to water, exported food and refused offers of humanitarian aid. As a result, a humanitarian catastrophe unfolded: hundreds of thousands died of starvation and brutal government-inflicted overwork in the countryside. To the Khmer Rouge, outside aid went against their principle of national self-reliance. According to Solomon Bashi, the Khmer Rouge exported 150,000 tons of rice in 1976 alone. In addition:

Coop chiefs often reported better yields to their supervisors than they had actually achieved. The coop was then taxed on the rice it reportedly produced. Rice was taken out of the people's mouths and given to the Center to make up for these inflated numbers [...] 'There were piles of rice as big as a house, but they took it away in trucks. We raised chickens and ducks and vegetables and fruit, but they took them all. You'd be killed if you tried to take anything for yourself.'[167]

According to Henri Locard, "the reputation of KR leaders for Spartan austerity is somewhat overdone. After all, they had the entire property of all expelled town dwellers at their full disposal, and they never suffered from malnutrition."[168]

Property was collectivized, and education was dispensed at communal schools. Children were raised on a communal basis. Even meals were prepared and eaten communally. Pol Pot's regime was extremely paranoid. Political dissent and opposition was not permitted. People were treated as opponents based on their appearance or background. Torture was widespread, thousands of politicians and bureaucrats accused of association with previous governments were executed. The régime turned Phnom Penh into a ghost city, while people in the countryside died of starvation or illnesses, or were simply killed.

Modern research has located 20,000 mass graves from the Khmer Rouge era all over Cambodia. Various studies have estimated the death toll at between 740,000 and 3,000,000—most commonly arriving at figures between 1.7 million and 2.2 million, with perhaps half of those deaths being due to executions, and the rest being attributable to starvation and disease.[169] Demographic analysis by Patrick Heuveline suggests that between 1.17 and 3.42 million Cambodians were killed.[170] Demographer Marek Sliwinski concluded that at least 1.8 million were killed from 1975 to 1979 on the basis of the total population decline.[171] Researcher Craig Etcheson of the Documentation Center of Cambodia suggests a death toll of between 2 and 2.5 million, with a "most likely" figure of 2.2 million. After five years of researching some 20,000 grave sites, he concludes that "these mass graves contain the remains of 1,386,734 victims of execution".[169][172] A UN investigation reported 2–3 million dead while UNICEF estimated that 3 million had been killed.[173] The Khmer Rouge themselves stated that 2 million had been killed—though they attributed those deaths to a subsequent Vietnamese invasion.[174] By late 1979, UN and Red Cross officials were warning that another 2.25 million Cambodians could die of starvation due to "the near destruction of Cambodian society under the regime of ousted Prime Minister Pol Pot",[175] most of whom were saved by international aid after the Vietnamese invasion.[176] An additional 300,000 Cambodians starved to death between 1979 and 1980, largely as a result of the after-effects of Khmer Rouge policies.[177]

Pol Pot aligned the country diplomatically with the People's Republic of China and adopted an anti-Soviet line. This alignment was more political and practical than it was ideological. Vietnam was aligned with the Soviet Union, so Cambodia aligned itself with the Asian rival of the Soviet Union and Vietnam (China had supplied the Khmer Rouge with weapons for years before they took power).

In December 1976, Pol Pot issued directives to the senior Khmer Rouge leadership to the effect that Vietnam was now an enemy. Defenses along the border were strengthened and unreliable deportees were moved deeper into Cambodia. Pol Pot's actions came in response to the Vietnamese Communist Party's fourth Congress (14 to 20 December 1976), which approved a resolution describing Vietnam's special relationship with Laos and Cambodia. It also talked of how Vietnam would forever be associated with the building and defense of the other two countries.

Unlike many communist leaders, Pol Pot never became the object of a personality cult. Even when he was in power, the CPK maintained the secrecy it had kept up during its years in the battlefield. For over two years after taking power, the party only referred to itself as Angkar ("Organization"). It was not until a speech on 15 April 1977 that Pol Pot revealed the CPK's existence. At that time, international observers confirmed the identification of Pol Pot as Saloth Sâr.

Conflict with Vietnam

In May 1975, a squad of Khmer Rouge soldiers raided and took the island of Phú Quốc. By 1977, relations with Vietnam began to fall apart. There were small border clashes in January. Pol Pot tried to prevent border disputes by sending a team to Vietnam. The negotiations failed, which caused even more border disputes. On 30 April, the Cambodian army, backed by artillery, crossed over into Vietnam. In attempting to explain Pol Pot's behavior, one region-watcher suggested that Cambodia was attempting to intimidate Vietnam by irrational acts into respecting or at least fearing Cambodia to the point they would leave the country alone. However, these actions only served to goad the Vietnamese people and government against the Khmer Rouge.

In May 1976, Vietnam sent its air force into Cambodia in a series of raids. In July, Vietnam forced a Treaty of Friendship on Laos that gave Vietnam almost total control over the country. In Cambodia, Khmer Rouge commanders in the Eastern Zone began to tell their men that war with Vietnam was inevitable and that once the war started their goal would be to recover parts of Vietnam (Khmer Krom) that were once part of Cambodia, whose people, they alleged, were struggling for independence from Vietnam. Whether these statements were the official policy of Pol Pot has never been confirmed.

In September 1977, Cambodia launched division-scale raids over the border, which once again left a trail of murder and destruction in villages. The Vietnamese claimed that around 1,000 people had been killed or injured. Three days after the raid, Pol Pot officially announced the existence of the formerly secret Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) and finally announced to the world that the country was a Communist state. In December, after having exhausted all other options, Vietnam sent 50,000 troops into Cambodia in what amounted to a short raid. The raid was meant to be secret. The Vietnamese withdrew after declaring that they had achieved their goals and the invasion was just a warning. Upon being threatened, the Vietnamese army promised to return with support from the Soviet Union. Pol Pot's actions made the operation much more visible than the Vietnamese had intended and they created a situation in which Vietnam appeared to be weak.

After making one final attempt to negotiate a settlement with Cambodia, Vietnam decided that it had to prepare for a full-scale war. Vietnam also tried to pressure Cambodia through China. However, China's refusal to pressure Cambodia and the flow of weapons from China into Cambodia were both signs that China also intended to act against Vietnam.

When Cambodian socialists rebelled in the eastern zone in May 1978, Pol Pot's armies could not crush them quickly. On 10 May, his radio broadcast a call not only to "exterminate the 50 million Vietnamese" but also to "purify the masses of the people" of Cambodia. Of 1.5 million easterners, branded as "Khmer bodies with Vietnamese minds", at least 100,000 were exterminated in six months. Later that year, in response to threats to its borders and the Vietnamese people, Vietnam attacked Cambodia to overthrow the Khmer Rouge, which Vietnam justified on the basis of self-defense.[178]

The Cambodian army was defeated, the regime was toppled and Pol Pot fled to the Thai border area. In January 1979, Vietnam installed a new government under Khmer Rouge defector Heng Samrin, composed of Khmer Rouge who had fled to Vietnam to avoid the purges. Pol Pot eventually regrouped with his core supporters in the Thai border area where he received shelter and assistance. At different times during this period, he was located on both sides of the border. The military government of Thailand used the Khmer Rouge as a buffer force to keep the Vietnamese away from the border. The Thai military also made money from the shipments of weapons from China to the Khmer Rouge. Eventually, Pol Pot rebuilt a small military force in the west of the country with the help of the People's Republic of China. The Sino-Vietnamese War began around this time.

The People's Republic of China was the main international supporter of the Khmer Rouge and its leader Pol Pot. The Chinese provided financial and military support to the party even after its overthrow in 1979.[179] The UN also recognized the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea, which included the Khmer Rouge, instead of the People's Republic of Kampuchea.

Pol Pot lived in the Phnom Malai area, giving interviews in the early 1980s and accusing all of those who opposed him of being traitors and "puppets" of the Vietnamese until he disappeared from public view. In 1985, his "retirement" was announced, but he retained his influence over the party.[180] A cadre interviewed during this period described Pol Pot's views on the death toll under his government:

He said that he knows that many people in the country hate him and think he's responsible for the killings. He said that he knows many people died. When he said this he nearly broke down and cried. He said he must accept responsibility because the line was too far to the left, and because he didn't keep proper track of what was going on. He said he was like the master in a house he didn't know what the kids were up to, and that he trusted people too much. For example, he allowed [one person] to take care of central committee business for him, [another person] to take care of intellectuals, and [a third person] to take care of political education. [...] These were the people to whom he felt very close, and he trusted them completely. Then in the end [...] they made a mess of everything [...] They would tell him things that were not true, that everything was fine, that this person or that was a traitor. In the end they were the real traitors. The major problem had been cadres formed by the Vietnamese.[181]

In December 1985, the Vietnamese launched a major offensive and overran most of the Khmer Rouge and other insurgent positions. The Khmer Rouge headquarters at Phnom Malai and its base near Pailin were completely destroyed, though the Vietnamese attackers suffered substantial losses during the attack.[182]

Pol Pot fled to Thailand where he lived for the next six years. His headquarters was a plantation villa near Trat.

Pol Pot officially resigned from the party in 1985 citing asthma as a contributing factor, but he continued to be the de facto leader of the Khmer Rouge and he also remained a dominant force within the anti-Vietnamese alliance. He handed day-to-day power to Son Sen, his hand-picked successor.

In 1986, his new wife Mea Son gave birth to a daughter, Sitha, (now Sar Patchata, wed in 2014), named after the heroine of the Khmer religious epic, the Reamker.[183] Shortly afterwards, Pol Pot moved to China for medical treatment for cancer. He remained there until 1988.

In 1989, Vietnam withdrew from Cambodia. The Khmer Rouge established a new stronghold in the west near the Thai border and Pol Pot relocated back into Cambodia from Thailand. Pol Pot refused to cooperate with the peace process, and he continued to fight against the new coalition government. The Khmer Rouge kept the government forces at bay until 1996, when troops started deserting. Several important Khmer Rouge leaders also defected. The government followed a policy of making peace with Khmer Rouge individuals and groups, after negotiations with the organization as a whole failed. In 1995, Pol Pot experienced a stroke that paralyzed the left side of his body.

Pol Pot ordered the execution of his lifelong right-hand man Son Sen on 10 June 1997 for attempting to make a settlement with the government. Eleven members of his family were also killed, although Pol Pot later denied that he had ordered this. He then fled his northern stronghold, but was later arrested by Khmer Rouge military Chief Ta Mok on 19 June 1997. Pol Pot had not been seen in public since 1980, two years after his overthrow at the hands of an invading Vietnamese army. He was sentenced to death in absentia by a Phnom Penh court soon afterwards.[184] In July, he was subjected to a show trial for the death of Son Sen and sentenced to lifelong house arrest.[185]

Death

On the night of 15 April 1998, two days before the 23rd anniversary of the Khmer Rouge takeover of Phnom Penh, the Voice of America, of which Pol Pot was a devoted listener, announced that the Khmer Rouge had agreed to turn him over to an international tribunal. According to his wife, he died in his bed later that night while waiting to be moved to another location. Ta Mok claimed that his death was due to heart failure.[186]

Ta Mok later described the way he died: "He was sitting in his chair waiting for the car to come. But he felt tired. His wife asked him to take a rest. He laid down on his bed. His wife heard a gasp of air. It was the sound of dying. When she touched him he had already died. It was at 10:15 last night".[187]

Despite government requests to inspect the body, it was cremated at Anlong Veng in the Khmer Rouge zone a few days later,[188] raising suspicions that he had committed suicide by taking an overdose of the medication which he had been prescribed.[189][190] Journalist Nate Thayer, who was present, held the view that Pol Pot killed himself when he became aware of Ta Mok's plan to hand him over to the United States.

Thayer confirmed that "Pol Pot died of a lethal dose of a combination of Valium and chloroquine".[191]

Political ideology

Pol Pot was influenced by Marxism and desired an entirely self sufficient agrarian society free from all foreign influence.[192] Stalin's work has been described as a "crucial formative influence" on Pol Pot's thought.[193] Also heavily influential was the work of Mao Zedong, particularly his On New Democracy.[62] In the mid-1960s, Pol Pot reformulated his ideas about Marxism–Leninism to better suit the Cambodian situation.[126]

In rejecting the revolutionary role of the proletariat, Pol Pot emphasised the idea of a revolutionary alliance between the peasantry and the intellectuals, an idea that Short linked to his reading of Kropotkin while in Paris.[194] He devised the idea that peasants could still develop a "proletarian consciousness" and that it was this approach which connected him with orthodox Marxist thought.[195] Philip Short thought that "the grammar of Theravada Buddhism permeated" Cambodian Marxist thought as much as Confucianism had influenced the development of Maoism in China.[194]

Pol Pot was an extreme nativist and xenophobe who sought to remove all ethnic and religious minorities from Kampuchea.[196][197][198] In addition, native religions were banned as part of the attempt to eliminate religion from the country.[199][200]

Personal life and characteristics

Pol Pot had a thirst for power.[201] He was introspective[202] and highly reclusive.[8] Short stated that he "delighted in appearing to be what he was not – a nameless face in the crowd".[203] During his political career, he used a wide array of pseudonyms: Pouk, Hay, Pol, 87, Grand-Uncle, Elder Brother, First Brother and in later years 99 and Phem.[204] He told a secretary that "the more often you change your name the better. It confuses the enemy".[204] In later life he concealed and falsified many details of his life.[8]

Pol Pot displayed what Chandler called a "genteel charisma",[205] with many observers commenting on his distinctive smile.[206] As a child, his brother characterized him as having been sweet tempered and equable while fellow school pupils recalled Pol Pot as having been mediocre, but pleasant.[205] As a teacher, he was characterized by his pupils as having been calm, honest and persuasive,[205] having an "evident good nature and attractive personality".[105] According to Short, Pol Pot's varied and eclectic upbringing meant that he was "able to communicate naturally with people of all sorts and conditions, establishing an instinctive rapport that invariably made them want to like him".[206]

Pol Pot had a nationalistic attitude and displayed little interest in events outside Cambodia.[202]

During his childhood, Pol Pot developed a love of music and romantic French poetry, with the work of Paul Verlaine being among his favorites.[35]

Works

- Long live the 17th anniversary of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (speech), New York: Group of Kampuchean Residents in America, 1977.

- Speech made by comrade Pol Pot, Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Kampuchea "At the banquet given in honour of the delegation of the Communist party of China and the government of the People's Republic of China. Phnom Penh, November 5, 1978." [Phnom Penh]: Dept. of Press and Information, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Democratic Kampuchea, 1978.

- Interview to the representatives of the Hong Kong's newspapers Wen wei po and Ta kun pao, Phnom Penh, September 21, 1978 [Phnom Penh]: Dept. of Press and Information, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Democratic Kampuchea, 1978.

- Interview of Comrade Pol Pot, Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Kampuchea, Prime Minister of the Government of Democratic Kampuchea to the delegation of Yugoslav journalists in visit to Democratic Kampuchea, March 17, 1978 [Phnom Penh]: Dept. of Press and Information, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Democratic Kampuchea, 1978.

- Talks with the delegation of the Sweden-Kampuchea Friendship Association [August 1978] [Phnom Penh]: Dept. of Press and Information, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Democratic Kampuchea, 1978.

- Let us continue to firmly hold aloft the banner of the victory of the glorious Communist Party of Kampuchea in order to defend Democratic Kampuchea, carry on socialist revolution and build up socialism: speech made by Comrade Pol Pot on the occasion of the 18th anniversary of the founding of the Communist Party of Kampuchea, Phnom Penh, September 27, 1978 [Phnom Penh]: Dept. of Press and Information, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Democratic Kampuchea, 1978.

- Talks with the delegation of the Association Belgium-Kampuchea, Phnom Penh, August 5, 1978 [Phnom Penh]: Dept. of Press and Information, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Democratic Kampuchea, 1978.

See also

- Cambodian Civil War

- Enemies of the People (film)

- First Indochina War

- Vietnam War – Second Indochina War

References

- 1 2 "BBC – History – Historic Figures: Pol Pot (1925–1998)". BBC. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- 1 2 Chandler, David (23 August 1999). "Pol Pot". Time Magazine. Archived from the original on 3 February 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ↑ "Pol Pot's daughter weds". The Phnom Penh Post. 17 March 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ↑ "Red Khmer", from the French rouge "red" (longtime symbol of socialism) and Khmer, the term for ethnic Cambodians.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 7; Short 2004, p. 15.

- 1 2 Short 2004, p. 18.

- 1 2 Short 2004, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 Chandler 1992, p. 7.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 8; Short 2004, p. 15, 18.

- 1 2 3 Chandler 1992, p. 8.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 16.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 20.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 14.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 8; Short 2004, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 9; Short 2004, p. 20.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 9; Short 2004, p. 21.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 23.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 17; Short 2004, p. 23.

- 1 2 3 Chandler 1992, p. 17.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 28.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 27.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 17; Short 2004, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 18; Short 2004, p. 28.

- 1 2 3 Chandler 1992, p. 22.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 19; Short 2004, p. 31.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 20; Short 2004, p. 31.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 19.

- ↑ Short 2004, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 21.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 36.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 21; Short 2004, p. 42.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 21; Short 2004, pp. 42–43.

- 1 2 Short 2004, p. 42.

- ↑ Short 2004, pp. 42–43.

- 1 2 Short 2004, p. 31.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 34.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 21; Short 2004, p. 37.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, pp. 23, 24; Short 2004, p. 37.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, pp. 23, 24.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 24.

- ↑ Short 2004, pp. 40–42.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 43.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, pp. 25, 27; Short 2004, p. 45.

- 1 2 3 Short 2004, p. 49.

- 1 2 Chandler 1992, p. 28.

- 1 2 Short 2004, p. 51.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 30; Short 2004, p. 50.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 30.

- 1 2 Chandler 1992, p. 34.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Short 2004, pp. 52, 59.

- 1 2 3 Short 2004, p. 63.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 64.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 68.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 62.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, pp. 22, 28; Short 2004, p. 66.

- 1 2 3 Short 2004, p. 66.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 27.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 69.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 34; Short 2004, p. 67.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 65.

- 1 2 Short 2004, p. 70.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 72.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 74.

- ↑ Short 2004, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 39; Short 2004, p. 79.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 80.

- 1 2 Short 2004, p. 83.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 28; Short 2004, p. 65, 82.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 42; Short 2004, p. 82.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, pp. 28, 42.

- ↑ Short 2004, pp. 85–86.

- ↑ Short 2004, pp. 88–89.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 87.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 89.

- ↑ Short 2004, pp. 89–90.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 90.

- ↑ Short 2004, pp. 90, 95.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 96.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 44; Short 2004, p. 96.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 100.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 45; Short 2004, p. 100.

- ↑ Short 2004, pp. 92–95.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, pp. 44–45; Short 2004, p. 95.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 101.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, pp. 45–46; Short 2004, pp. 103–104.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 46; Short 2004, p. 104.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 46; Short 2004, pp. 104–105.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 105.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 48.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, pp. 46, 48; Short 2004, p. 106.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, pp. 47–48; Short 2004, pp. 107–108.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 49; Short 2004, pp. 109–110.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, pp. 49, 51; Short 2004, pp. 110–112.

- ↑ Short 2004, pp. 112–113.

- ↑ Short 2004, pp. 113–114.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 47; Short 2004, p. 116.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 54.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 52; Short 2004, p. 120.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 54; Short 2004, pp. 120.

- ↑ Short 2004, pp. 116–117.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 117.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 52; Short 2004, p. 118.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 116.

- 1 2 Short 2004, p. 120.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 121.

- ↑ Short 2004, pp. 121–122.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 122.

- ↑ Short 2004, pp. 135–136.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 62.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, pp. 61–62; Short 2004, p. 138.

- ↑ Short 2004, pp. 139–140.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 63; Short 2004, p. 140.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, pp. 63–64; Short 2004, p. 141.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 141.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 66; Short 2004, pp. 141–142.

- ↑ Short 2004, pp. 124–125.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 127.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 60; Short 2004, pp. 131–32.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 66; Short 2004, pp. 142–143.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 67; Short 2004, p. 144.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 67.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 145.

- 1 2 3 Short 2004, p. 146.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 147.

- 1 2 Short 2004, p. 148.

- ↑ Short 2004, pp. 148–149.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 149.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 152.

- ↑ Short 2004, pp. 156–157.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 157.

- ↑ Short 2004, pp. 158–159.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 159.

- ↑ Short 2004, pp. 159–160.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 161.

- ↑ Short 2004, pp. 161–162.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 162.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 170.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 172.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 173.

- 1 2 3 4 Short 2004, p. 174.

- 1 2 Short 2004, p. 175.

- 1 2 3 Short 2004, p. 176.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 177.

- ↑ Short 2004, pp. 180–182.

- ↑ Hinton, Alexander Laban (2005). Why Did They Kill: Cambodia in the Shadow of Genocide. University of California Press. p. 382.

- ↑ Lahneman, William J. (2004). Military Intervention: Cases in Context for the Twenty-First Century. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 97.

- ↑ Whatley, Stuart (6 April 2009). "Khmer Rouge Defendent [sic]: US Policies Enabled Cambodian Genocide". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- ↑ Jose, Alice (10 November 1993). "Continuity and change in India's Cambodia policy" (PDF). Shodhganga. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ↑ See Pol Pot: Anatomy of a Nightmare, p. 212.

- ↑ Ferlus, Michel (2011). "Toward Proto Pearic: problems and historical implications". Mon-Khmer Studies (Special Issue No. 2): 38–51. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ↑ Mydans, Seth (17 April 1998). "DEATH OF POL POT; Pol Pot, Brutal Dictator Who Forced Cambodians to Killing Fields, Dies at 73". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- 1 2 Short 2005, p. 288

- ↑ Short 2005, p. 290

- ↑ Short 2005, p. 289

- ↑ Anderson, Jack; Whitten, Les (4 June 1975). "Genocide in Cambodia?". The Washington Post.

In CIA jargon, the agency has "no assets" left in Cambodia. The analysts can only make agonizing guesses about what has happened to the three million men, women, and children. For many, the forced evacuation must have been a death march. The aged and the ailing probably didn't survive the trek. Patients were even cleared out of the hospitals and herded into the hinterland with the rest ... There also aren't enough food stocks in the backwoods ... Analysts believe that hundreds of thousands will die of starvation. One shocking estimate is that at least a million people will perish. It appears that the Khmer Rouge, as all Cambodian communists call themselves, may be guilty of genocide against their own people ... There also have been reports, including some intercepted messages, that the communists are executing the entire families of former military officers and high civilian officials.

- ↑ Anderson, Jack (23 June 1975). "UN Ignores Death March in Cambodia". The Washington Post.

This must go down in history as the greatest atrocity since the Nazis herded Jews into the gas chambers.

- ↑ Quoted in Short 2005, p. 288

- ↑ Jackson, Karl D. (2014). "The Ideology of Total Revolution". In Jackson, Karl D. Cambodia, 1975–1978: Rendezvous with Death. Princeton University Press. p. 52. ISBN 9781400851706. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

[...] the population of Democratic Kampuchea was divided into three categories, based on their class backgrounds and their political pasts: individuals with full rights (penh sith), those who were candidates for full rights (triem), and those who had no rights whatsoever (bannheu). [...] The lowest category, the bannheu or depositees, had no rights whatsoever, not even the right to food. These were former landowners, army officers, bureaucrats, teachers, merchants, and urban residents [...].

- ↑ Children of Cambodia's Killing Fields, Worms from Our Skin. Teeda Butt Mam. Memoirs compiled by Dith Pran. 1997, Yale University. ISBN 978-0-300-07873-2. Excerpts available from Google Books.

- ↑ Wessinger, Catherine (2000). Millennialism, Persecution, and Violence: Historical Cases. Syracuse University Press. p. 282. ISBN 9780815628095.

Democratic Kampuchea was officially an atheist state, and the persecution of religion by the Khmer Rouge was matched in severity only by the persecution of religion in the communist states of Albania and North Korea, so there were not any direct historical continuities of Buddhism into the Democratic Kampuchea era.

- ↑ Juergensmeyer, Mark. The Oxford Handbook of Global Religions. Oxford University Press. p. 495.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Quinn-Judge, Westad, Odd Arne, Sophie. The Third Indochina War: Conflict Between China, Vietnam and Cambodia, 1972–79. Routledge. p. 189.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Philip Shenon, Phnom Penh Journal; Lord Buddha Returns, With Artists His Soldiers The New York Times – 2 January 1992

- ↑ Ben Kiernan. "The Cambodian Genocide, 1975–1979, Genocide against ethnic groups" (PDF). NIOD, instituut voor oorlogs-, holocaust- en genocidestudiesy. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ↑ "Literacy and Education under the Khmer Rouge". The Cambodian Genocide Program, Yale University. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ↑ Solomon Bashi (2010), "Prosecuting Starvation at the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia," ExpressO.

- ↑ Locard, Henri, State Violence in Democratic Kampuchea (1975–1979) and Retribution (1979–2004), European Review of History, Vol. 12, No. 1, March 2005, pp. 121–143.

- 1 2 Bruce Sharp (2008) Counting Hell, discusses the various estimates.

- ↑ Heuveline, Patrick (2001). "The Demographic Analysis of Mortality in Cambodia." In Forced Migration and Mortality, eds. Holly E. Reed and Charles B. Keely. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

- ↑ Marek Sliwinski, Le Génocide Khmer Rouge: Une Analyse Démographique (L'Harmattan, 1995), pp. 41–48, 57.

- ↑ Documentation Center of Cambodia Archived 28 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ William Shawcross, The Quality of Mercy: Cambodia, Holocaust, and Modern Conscience (Touchstone, 1985), pp. 115–116.

- ↑ Khieu Samphan, Interview, Time, 10 March 1980.

- ↑ Hersh, Seymour M. (8 August 1979). "2.25 million Cambodians Facing Starvation". The New York Times.

U.N. and Red Cross officials said here and in Ho Chi Minh city this week that 2.25 million Cambodians were facing imminent starvation ... "I have seen quite a few ravaged countries in my career, but nothing like this," one official said ... Cambodia's social welfare apparatus has been left in shambles, the relief officials said, citing the demolition of hospitals, schools, water supply facilities and sanitary systems ... Intellectuals were systematically purged ... Of more than 500 doctors known to have been practising medicine in Cambodia before the defeat of the Lon Nol regime by the communist forces...only 40 have been found ... Every home had been systematically ransacked ... All signs of modern civilization—typewriters, radios, television sets, phonographs, books—were destroyed ... A Roman Catholic cathedral in the center of Phonm Penh had been razed ... The former regime was scrupulously methodical in its destruction of hospitals ... Cambodia's fall harvest [is] expected to yield almost nothing.

- ↑ William Shawcross, The Quality of Mercy: Cambodia, Holocaust, and Modern Conscience (Touchstone, 1985), discusses at length the international famine relief effort.

- ↑ Heuveline, Patrick (2001). "The Demographic Analysis of Mortality Crises: The Case of Cambodia 1970–1979". Forced Migration and Mortality. National Academies Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-309-07334-9.

- ↑ Kiernan, Ben (April 1993). "The Original Cambodian". 242. New Internationalist. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- ↑ Carvin, Andy "KR Years: The fall of the Khmer Rouge"

- ↑ "Kelvin Rowley, ''Second Life, Second Death: The Khmer Rouge After 1978''" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ Quoted in David P. Chandler, Brother Number One: A Political Biography of Pol Pot, Silkworm Books, Chiang Mai, 2000.

- ↑ "R. R. Ross, ''Current Indochinese Issues''" (PDF). Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ Short 2005, p. 423

- ↑ "Pol Pots Khmer Rouge denounces him". CNN. 17 June 1997. Archived from the original on 18 September 2011.

- ↑ Nate Thayer, "Dying Breath The inside story of Pol Pot's last days and the disintegration of the movement he created," Far Eastern Economic Review, April 30, 1998 Archived 19 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Nate Thayer. "Dying Breath" Far Eastern Economic Review. 30 April 1998.

- ↑ David P. Chandler, Brother Number One: A Political Biography of Pol Pot, Westview Press, Boulder, CO., 1999, p. 186.

- ↑ Footage on YouTube of the body of Pol Pot.

- ↑ Gittings, John; Tran, Mark (21 January 1999). "Pol Pot 'killed himself with drugs'". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ Chan, Sucheng (2004). Survivors: Cambodian Refugees in the United States. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0252071799.

- ↑ Teresa Poole, "Pol Pot `suicide' to avoid US trial", The Independent, London, 21 January 1999.

- ↑ Taylor, Adam (7 August 2014). "Why the world should not forget Khmer Rouge and the killing fields of Cambodia". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 67.

- 1 2 Short 2004, p. 150.

- ↑ Short 2004, pp. 149–150.

- ↑ Vollmann, William T. (27 February 2005). "'Pol Pot': The Killer's Smile". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ↑ "GENOCIDE – CAMBODIA". www.ppu.org.uk. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ↑ "The Survival of Cambodia's Ethnic Minorities". Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ↑ "Pol Pot - Facts & Summary - HISTORY.com". HISTORY.com. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ↑ "Khmer Rouge Ideology | Holocaust Memorial Day Trust". hmd.org.uk. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ↑ Chandler 1992, p. 3.

- 1 2 Chandler 1992, p. 6.

- ↑ Short 2004, p. 6.

- 1 2 Short 2004, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 Chandler 1992, p. 5.

- 1 2 Short 2004, p. 44.

Sources

Further reading

- Denise Affonço, To The End Of Hell: One Woman's Struggle to Survive Cambodia's Khmer Rouge.

- David P. Chandler, Ben Kiernan & Chanthou Boua: Pol Pot plans the future: Confidential leadership documents from Democratic Kampuchea, 1976–1977. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1988.

- Stephen Heder, Pol Pot and Khieu Samphan. Clayton, Victoria: Centre of Southeast Asian Studies, 1991.

- Ben Kiernan, "Social Cohesion in Revolutionary Cambodia", Australian Outlook, December 1976.

- Ben Kiernan, "Vietnam and the Governments and People of Kampuchea", Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars (October–December 1979)