Soviet Union–United States relations

| |

Soviet Union |

United States |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic Mission | |

| Soviet Embassy, Washington, D.C. | United States Embassy, Moscow |

The relations between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (1922–1991) succeeded the previous relations from 1776 to 1917 and predate today's relations that began in 1992. Full diplomatic relations between the two countries were established late (1933) due to mutual hostility. During World War II, the two countries were briefly allies. At the end of the war, the first signs of post-war mistrust and hostility began to appear between the two countries, escalating into the Cold War; a period of tense hostile relations, with periods of détente.

Country comparison

| Common name | Soviet Union | United States |

|---|---|---|

| Official name | Union of Soviet Socialist Republics | United States of America |

| Coat of arms |  |

.svg.png) |

| Flag |  |

|

| Area | 22,402,200 km² (8,649,538 sq mi) | 9,526,468 km² (3,794,101 sq mi)[1] |

| Population | 293,047,571 (1991) | 252,127,402 (1991) |

| Population density | 13.1 /km² (33.9 /sq mi) | 33.7/km² (87.4/sq mi) |

| Capital | Moscow | Washington, D.C. |

| Largest metropolitan areas | Moscow | New York City |

| Government | Federal Marxist–Leninist one-party socialist state | Federal presidential constitutional republic two-party system |

| Political parties | Communist Party of the Soviet Union | Democratic Party Republican Party |

| Most common language | Russian | English |

| Currency | Soviet ruble | US dollar |

| GDP (nominal) | $2.659 trillion (~$9,896 per capita) | $5.23 trillion (~$20,624 per capita) |

| Intelligence agencies | Committee for State Security (KGB) | Central Intelligence Agency |

| Military expenditures | $290 billion (1990) | $409.7 billion (1990) |

| Navy size | Soviet Navy (1990)[2]

|

US Navy (1990)

|

| Air force size | Soviet Air Force (1990)[3]

|

US Air Force (1990)

|

| Nuclear warheads (total) | 37,000 (1990) | 10,904 (1990) |

| Economic alliance | Comecon | European Economic Community Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| Military alliance | Warsaw Pact | NATO |

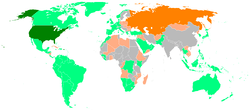

| Countries allied during the Cold War | Warsaw Pact:

Soviet Republics seat in the United Nations: Baltic States as Soviet Republics: Other Soviet Socialist Republics:

Other allies:

|

NATO:

Status of the Baltic States during occupation: Other allies:

|

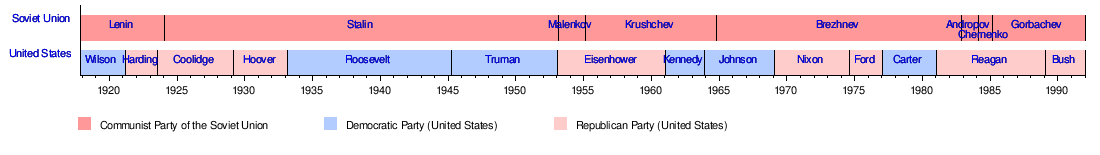

Leaders of the Soviet Union and the United States from 1917 to 1991.

Pre-World War II relations

1917–1932

In 1921, after the Bolsheviks took over Russia, won a Civil War, killed the royal family, repudiated the tsarist debt, and called for a world revolution by the working class, it became a pariah nation.

U.S. hostility towards the Bolsheviks was not only due to countering the emergence of an anti-capitalist revolution. The Americans, as a result of the fear of Japanese expansion into Russian held territory and their support for the Allied-aligned Czech legion, sent a small number of troops to Northern Russia and Siberia. After Lenin came to power in the October Revolution, he withdrew Russia from World War I, allowing the Germans to reallocate troops to face the Americans and other Allied forces on the Western Front.[4]

U.S. attempts at hindering the Bolsheviks consisted less of direct military intervention than various forms of aid directed to anti-Bolshevik groups, especially the White Army. Aid was given mostly by means of supplies and food. President Woodrow Wilson had various issues to deal with and did not want to intervene in Russia with total commitment due to Russian public opinion and the belief that many Russians were not part of the growing Red Army and in the hopes the revolution would eventually fade towards more democratic realizations. An aggressive invasion would have allied Russians together and depicted the U.S. as an invading conquering nation. Following World War I, Germany was seen as the puppeteer in the Bolshevik cause with indirect control of the Bolsheviks through German agents.[5]

"The fact is that while Germany in a way has been using the Bolshevik element either directly through bribes of some of its leaders or as a result of the principles of government they espouse and practice, Germany is appealing to the conservative elements of Russia as their only hope against the Bolsheviks".[6]

Beyond the Russian Civil War, relations were also dogged by claims of American companies receiving compensation for the nationalized industries they had invested in.[7]

By 1922, the Soviet Union was working its way back into European favor. The United States refused formal recognition, but did open trade relations and there was active transfer of technology.[8] The Ford Motor Company took the lead in building a truck industry and introducing tractors.[9]

Recognition in 1933

By 1933, old fears of Communist threats had faded, and the American business community, as well as newspaper editors, were calling for diplomatic recognition. President Franklin D. Roosevelt was eager for large-scale trade with Russia, and hope for some repayment on the old tsarist debts. He negotiated with the Soviets, and they promised there would be no espionage so Roosevelt used presidential authority to normalized relations in November 1933.[10] There were few complaints about the move.[11] However, there was no progress on the debt issue, and little additional trade. Historians Justus D. Doenecke and Mark A. Stoler note that, "Both nations were soon disillusioned by the accord."[12] Many American businessmen expected a bonus in terms of large-scale trade, but it never materialized.[13]

The Soviets had promised not to engage in spying inside the United States, but did so anyhow.[14] Roosevelt named William Bullitt as ambassador from 1933 to 1936. Bullitt arrived in Moscow with high hopes for Soviet–American relations, his view of the Soviet leadership soured on closer inspection. By the end of his tenure, Bullitt was openly hostile to the Soviet government. He remained an outspoken anti-communist for the rest of his life.[15]

World War II (1939–45)

Before the Germans decided to invade the Soviet Union in June 1941, relations remained strained, as the Soviet invasion of Finland, Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, Soviet invasion of the Baltic states and Joint German and Soviet invasion of Poland stirred, which resulted in Soviet Union's expulsion from the League of Nations. Come the invasion of 1941, the Soviet Union entered a Mutual Assistance Treaty with Great Britain, and received aid from the American Lend-Lease program, relieving American-Soviet tensions, and bringing together former enemies in the fight against Nazi Germany and the Axis powers.

Though operational cooperation between the United States and the Soviet Union was notably less than that between other allied powers, the United States nevertheless provided the Soviet Union with huge quantities of weapons, ships, aircraft, rolling stock, strategic materials, and food through the Lend-Lease program. The Americans and the Soviets were as much for war with Germany as for the expansion of an ideological sphere of influence. During the war, Truman stated that it did not matter to him if a German or a Russian soldier died so long as either side is losing.[16]

The American Russian Cultural Association (Russian: Американо–русская культурная ассоциация) was organized in the USA in 1942 to encourage cultural ties between the Soviet Union and the United States, with Nicholas Roerich as honorary president. The group's first annual report was issued the following year. The group does not appear to have lasted much past Nicholas Roerich's death in 1947.[17][18]

In total, the U.S. deliveries through Lend-Lease amounted to $11 billion in materials: over 400,000 jeeps and trucks; 12,000 armored vehicles (including 7,000 tanks, about 1,386[19] of which were M3 Lees and 4,102 M4 Shermans);[20] 11,400 aircraft (4,719 of which were Bell P-39 Airacobras)[21] and 1.75 million tons of food.[22]

Roughly 17.5 million tons of military equipment, vehicles, industrial supplies, and food were shipped from the Western Hemisphere to the USSR, 94% coming from the US. For comparison, a total of 22 million tons landed in Europe to supply American forces from January 1942 to May 1945. It has been estimated that American deliveries to the USSR through the Persian Corridor alone were sufficient, by US Army standards, to maintain sixty combat divisions in the line.[23][24]

The United States delivered to the Soviet Union from October 1, 1941 to May 31, 1945 the following: 427,284 trucks, 13,303 combat vehicles, 35,170 motorcycles, 2,328 ordnance service vehicles, 2,670,371 tons of petroleum products (gasoline and oil) or 57.8 percent of the High-octane aviation fuel,[25] 4,478,116 tons of foodstuffs (canned meats, sugar, flour, salt, etc.), 1,911 steam locomotives, 66 Diesel locomotives, 9,920 flat cars, 1,000 dump cars, 120 tank cars, and 35 heavy machinery cars. Provided ordnance goods (ammunition, artillery shells, mines, assorted explosives) amounted to 53 percent of total domestic production.[25] One item typical of many was a tire plant that was lifted bodily from the Ford Company's River Rouge Plant and transferred to the USSR. The 1947 money value of the supplies and services amounted to about eleven billion dollars.[26]

Cold War (1945–91)

| |

United States |

Soviet Union |

|---|---|

The end of World War II saw the resurgence of previous divisions between the two nations. The expansion of Soviet influence into Eastern Europe following Germany's defeat worried the liberal democracies of the West, particularly the United States, which had established virtual economic and political primacy in Western Europe. The two nations promoted two opposing economic and political ideologies and the two nations competed for international influence along these lines. This protracted a geopolitical, ideological, and economic struggle—lasting from about 1947 to the period leading to the dissolution of the Soviet Union on December 26, 1991—is known as the Cold War.

The Soviet Union detonated its first nuclear weapon in 1949, ending the United States' monopoly on nuclear weapons. The United States and the Soviet Union engaged in a conventional and nuclear arms race that persisted until the collapse of the Soviet Union. Andrei Gromyko was Minister of Foreign Affairs of the USSR, and is the longest-serving foreign minister in the world.

After Germany's defeat, the United States sought to help its Western European allies economically with the Marshall Plan. The United States extended the Marshall Plan to the Soviet Union, but under such terms, the Americans knew the Soviets would never accept, namely the acceptance of free elections, not characteristic of Stalinist communism. With its growing influence on Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union sought to counter this with the Comecon in 1949, which essentially did the same thing, though was more an economic cooperation agreement instead of a clear plan to rebuild. The United States and its Western European allies sought to strengthen their bonds and spite the Soviet Union. They accomplished this most notably through the formation of NATO which was basically a military agreement. The Soviet Union countered with the Warsaw Pact, which had similar results with the Eastern Bloc.

In December 1989, both the leaders of the United States and the Soviet Union declared the Cold War over, and in 1991, the two were partners in the Gulf War against Iraq, a longtime Soviet ally. On 31 July 1991, the START I treaty cutting the number of deployed nuclear warheads of both countries was signed by Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev and U.S. President George Bush. However, many consider the Cold War to have truly ended in late 1991 with the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

See also

References

- ↑ "United States". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ↑ "Soviet Navy Ships - 1945-1990 - Cold War". GlobalSecurity.org.

- 1 2 a1c80d6c8fdb/UploadedImages/Mitchell%20Publications/Arsenal%20of%20Airpower. pdf "Arsenal of Airpower" Check

|url=value (help). the99percenters.net. March 13, 2012. Retrieved July 28, 2016 – via Washington Post. - ↑ Fic, Victor M (1995), The Collapse of American Policy in Russia and Siberia, 1918, Colombia University Press, New York

- ↑ Scott Reed (May 2007), American "Intervention" in the Russian Civil War: 1918–1920 – Why did President Woodrow Wilson decide to send American troops into Siberia and Northern Russia on August 16, 1918?, International Academy

- ↑ Levin, N (1970), Gordon Jr. Woodrow Wilson and World Politics: America's Response to War and Revolution, Oxford University Press, New York, p. 19

- ↑ Donald E. Davis and Eugene P. Trani (2009). Distorted Mirrors: Americans and Their Relations with Russia and China in the Twentieth Century. University of Missouri Press. p. 48.

- ↑ Kendall E. Bailes, "The American Connection: Ideology and the Transfer of American Technology to the Soviet Union, 1917–1941." Comparative Studies in Society and History 23#3 (1981): 421-448.

- ↑ Dana G. Dalrymple, "The American tractor comes to Soviet agriculture: The transfer of a technology." Technology and Culture 5.2 (1964): 191-214.

- ↑ Smith 2007, pp. 341–343.

- ↑ Paul F. Boller (1996). Not So!: Popular Myths about America from Columbus to Clinton. Oxford UP. pp. 110–14.

- ↑ Justus D. Doenecke and Mark A. Stoler (2005). Debating Franklin D. Roosevelt's Foreign Policies, 1933-1945. pp. 18. 121.

- ↑ Joan H. Wilson, "American Business and the Recognition of the Soviet Union." Social Science Quarterly (1971): 349-368. in JSTOR

- ↑ Edward Moore Bennett, Franklin D. Roosevelt and the search for security: American-Soviet relations, 1933-1939 (1985).

- ↑ Will Brownell and Richard Billings, So Close to Greatness: The Biography of William C. Bullitt (1988)

- ↑ "National Affairs: Anniversary Remembrance". Time magazine. 2 July 1951. Retrieved 2013-10-12.

- ↑ "American-Russian Cultural Association". roerich-encyclopedia. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ↑ "Annual Report". onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ↑ Zaloga (Armored Thunderbolt) p. 28, 30, 31

- ↑ Lend-Lease Shipments: World War II, Section IIIB, Published by Office, Chief of Finance, War Department, 31 December 1946, p. 8.

- ↑ Hardesty 1991, p. 253

- ↑ World War II The War Against Germany And Italy, US Army Center Of Military History, page 158.

- ↑ "The five Lend-Lease routes to Russia". Engines of the Red Army. Archived from the original on 4 September 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ↑ Motter, T.H. Vail (1952). The Persian Corridor and Aid to Russia. Center of Military History. pp. 4–6. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- 1 2 Weeks 2004, p. 9

- ↑ Deane, John R. 1947. The Strange Alliance, The Story of Our Efforts at Wartime Co-operation with Russia. The Viking Press.

Further reading

- Bennett, Edward M. Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Search for Security: American-Soviet Relations, 1933-1939 (1985)

- Bennett, Edward M. Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Search for Victory: American-Soviet Relations, 1939-1945 (1990).

- Cohen, Warren I. The Cambridge History of American Foreign Relations: Vol. IV: America in the Age of Soviet Power, 1945-1991 (1993).

- Crockatt, Richard. The Fifty Years War: The United States and the Soviet Union in world politics, 1941-1991 (1995).

- Diesing, Duane J. Russia and the United States: Future Implications of Historical Relationships (No. Au/Acsc/Diesing/Ay09. Air Command And Staff Coll Maxwell Afb Al, 2009). online

- Dunbabin, J.P.D. International Relations since 1945: Vol. 1: The Cold War: The Great Powers and their Allies (1994).

- Foglesong, David S. The American mission and the 'Evil Empire': the crusade for a 'Free Russia' since 1881 (2007).

- Gaddis, John Lewis. The United States and the Origins of the Cold War, 1941-1947 (2000).

- Glantz, Mary E. FDR and the Soviet Union: the President's battles over foreign policy (2005).

- Jensen, Ronald J. The Alaska Purchase and Russian-American Relations (1973).

- LaFeber, Walter. America, Russia, and the Cold War 1945-2006 (2008).

- Leffler, , Melvyn P. The Specter of Communism: The United States and the Origins of the Cold War, 1917-1953 (1994).

- Saul, Norman E. War and Revolution: The United States and Russia, 1914-1921 (2001).

- Saul, Norman E. Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Foreign Policy (2014).

- Sibley, Katherine AS. "Soviet industrial espionage against American military technology and the US response, 1930–1945." Intelligence and National Security 14.2 (1999): 94-123.

- Sokolov, Boris V. "The role of lend‐lease in Soviet military efforts, 1941–1945." Journal of Slavic Military Studies 7.3 (1994): 567-586.\

- Stoler, Mark A. Allies and Adversaries: The Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Grand Alliance, and US Strategy in World War II. (UNC Press, 2003).

- Taubman, William. Stalin’s American Policy: From Entente to Détente to Cold War (1982).

- Thomas, Benjamin P.. Russo-American Relations: 1815-1867 (1930).

- Trani, Eugene P. "Woodrow Wilson and the decision to intervene in Russia: a reconsideration." Journal of Modern History 48.3 (1976): 440-461.

- Unterberger, Betty Miller. "Woodrow Wilson and the Bolsheviks: The 'Acid Test' of Soviet–American Relations." Diplomatic History 11.2 (1987): 71-90.

- White, Christine A. British and American Commercial Relations with Soviet Russia, 1918-1924 (UNC Press Books, 2017).