Sino-Indian border dispute

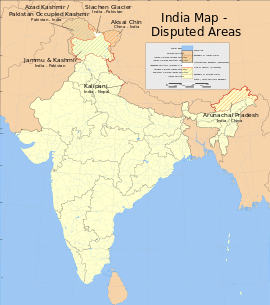

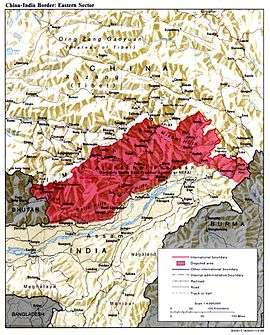

Sovereignty over two separated pieces of territory have been contested between China and India. Aksai Chin is located either in the Indian province of Jammu and Kashmir, or the Chinese province of Xinjiang, in the west. It is a virtually uninhabited high-altitude wasteland crossed by the Xinjiang-Tibet Highway. The other disputed territory lies south of the McMahon Line. It was formerly referred to as the North East Frontier Agency, and is now called Arunachal Pradesh. The McMahon Line was part of the 1914 Simla Convention between British India and Tibet, an agreement rejected by China.[1]

The 1962 Sino-Indian War was fought in both of these areas. An agreement to resolve the dispute was concluded in 1996, including "confidence-building measures" and a mutually agreed Line of Actual Control. In 2006, the Chinese ambassador to India claimed that all of Arunachal Pradesh is Chinese territory[2] amidst a military buildup.[3] At the time, both countries claimed incursions as much as a kilometre at the northern tip of Sikkim.[4] In 2009, India announced it would deploy additional military forces along the border.[5] In 2014, India proposed China should acknowledge "One India" policy to resolve the border dispute.[6][7]

Background

Aksai Chin

From the area's lowest point (on the Karakash River at about 14,000 feet (4,300 m) to the glaciated peaks up to 22,500 feet (6,900 m) above sea level, this is a desolate, largely uninhabited area. It covers an area of about 37,244 square kilometres (14,380 sq mi). The desolation of Aksai Chin meant that it had no significant human importance other than ancient trade routes crossing it, providing brief passage during summer for caravans of yaks from Xinjiang and Tibet.[8]

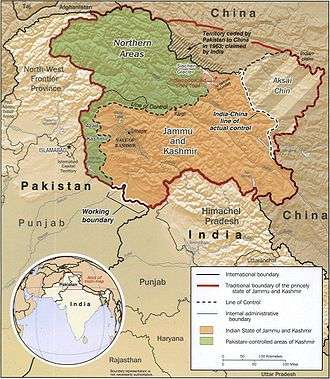

One of the earliest treaties regarding the boundaries in the western sector was issued in 1842. The Sikh Empire of the Punjab region had annexed Ladakh into the state of Jammu in 1834. In 1841, they invaded Tibet with an army. Chinese forces defeated the Sikh army and in turn entered Ladakh and besieged Leh. After being checked by the Sikh forces, the Chinese and the Sikhs signed a treaty in September 1842, which stipulated no transgressions or interference in the other country's frontiers.[9] The British defeat of the Sikhs in 1846 resulted in transfer of sovereignty over Ladakh to the British, and British commissioners attempted to meet with Chinese officials to discuss the border they now shared. However, both sides were sufficiently satisfied that a traditional border was recognised and defined by natural elements, and the border was not demarcated.[9] The boundaries at the two extremities, Pangong Lake and Karakoram Pass, were reasonably well-defined, but the Aksai Chin area in between lay largely undefined.[8][10]

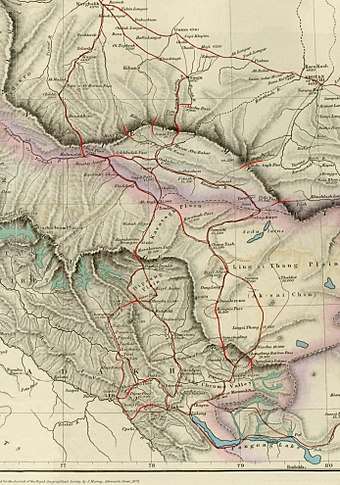

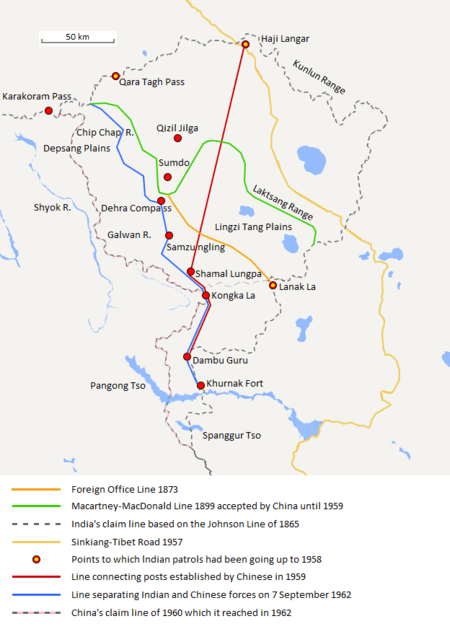

The Johnson Line

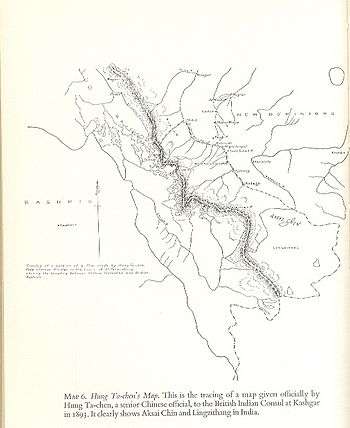

W. H. Johnson, a civil servant with the Survey of India proposed the "Johnson Line" in 1865, which put Aksai Chin in Jammu and Kashmir. This was the time of the Dungan revolt, when China did not control Xinjiang, so this line was never presented to the Chinese. Johnson presented this line to the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir, who then claimed the 18,000 square kilometres contained within his territory[11] and by some accounts he claimed territory further north as far as the Sanju Pass in the Kun Lun Mountains. Johnson's work was severely criticised for gross inaccuracies, with description of his boundary as "patently absurd",[1] and he was reprimanded by the British Government and resigned from the Survey.[1][11][12] The Maharajah of Jammu and Kashmir constructed a fort at Shahidulla (modern-day Xaidulla), and had troops stationed there for some years to protect caravans.[13] Eventually, most sources placed Shahidulla and the upper Karakash River firmly within the territory of Xinjiang (see accompanying map). According to Francis Younghusband, who explored the region in the late 1880s, there was only an abandoned fort and not one inhabited house at Shahidulla when he was there – it was just a convenient staging post and a convenient headquarters for the nomadic Kirghiz.[14] The abandoned fort had apparently been built a few years earlier by the Dogras.[15] In 1878 the Chinese had reconquered Xinjiang, and by 1890 they already had Shahidulla before the issue was decided.[11] By 1892, China had erected boundary markers at Karakoram Pass.[1]

In 1897 a British military officer, Sir John Ardagh, proposed a boundary line along the crest of the Kun Lun Mountains north of the Yarkand River.[13] At the time Britain was concerned at the danger of Russian expansion as China weakened, and Ardagh argued that his line was more defensible. The Ardagh line was effectively a modification of the Johnson line, and became known as the "Johnson-Ardagh Line".

The Macartney-Macdonald Line

In 1893, Hung Ta-chen, a senior Chinese official at St. Petersburg, gave maps of the region to George Macartney, the British consul general at Kashgar, which coincided in broad details.[16] In 1899, Britain proposed a revised boundary, initially suggested by Macartney and developed by the Governor General of India Lord Elgin. This boundary placed the Lingzi Tang plains, which are south of the Laktsang range, in India, and Aksai Chin proper, which is north of the Laktsang range, in China. This border, along the Karakoram Mountains, was proposed and supported by British officials for a number of reasons. The Karakoram Mountains formed a natural boundary, which would set the British borders up to the Indus River watershed while leaving the Tarim River watershed in Chinese control, and Chinese control of this tract would present a further obstacle to Russian advance in Central Asia.[12] The British presented this line, known as the Macartney-MacDonald Line, to the Chinese in 1899 in a note by Sir Claude MacDonald. The Qing government did not respond to the note, and the British took that as Chinese acquiescence.[11] Although no official boundary had ever been negotiated, China believed that this had been the accepted boundary.[17][18]

1899 to 1947

Both the Johnson-Ardagh and the Macartney-MacDonald lines were used on British maps of India.[11] Until at least 1908, the British took the Macdonald line to be the boundary,[19] but in 1911, the Xinhai Revolution resulted in the collapse of central power in China, and by the end of World War I, the British officially used the Johnson Line. However they took no steps to establish outposts or assert actual control on the ground. In 1927, the line was adjusted again as the government of British India abandoned the Johnson line in favour of a line along the Karakoram range further south. However, the maps were not updated and still showed the Johnson Line.[1]

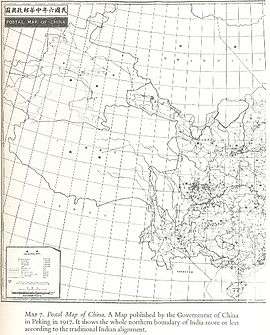

From 1917 to 1933, the "Postal Atlas of China", published by the Government of China in Peking had shown the boundary in Aksai Chin as per the Johnson line, which runs along the Kunlun mountains.[16][18] The "Peking University Atlas", published in 1925, also put the Aksai Chin in India.[20]:101 When British officials learned of Soviet officials surveying the Aksai Chin for Sheng Shicai, warlord of Xinjiang in 1940–1941, they again advocated the Johnson Line.[11] At this point the British had still made no attempts to establish outposts or control over the Aksai Chin, nor was the issue ever discussed with the governments of China or Tibet, and the boundary remained undemarcated at India's independence.[1][11]

Since 1947

Upon independence in 1947, the government of India used the Johnson Line as the basis for its official boundary in the west, encompassing Aksai Chin.[1] However, India did not claim the northern areas near Shahidulla and Khotan, for including which in Indian territory, among other things, Johnson had been criticised. From the Karakoram Pass (which is not under dispute), the Indian claim line extends northeast of the Karakoram Mountains north of the salt flats of the Aksai Chin, to set a boundary at the Kunlun Mountains, and incorporating part of the Karakash River and Yarkand River watersheds. From there, it runs east along the Kunlun Mountains, before turning southwest through the Aksai Chin salt flats, through the Karakoram Mountains, and then to Pangong Lake.[8]

On 1 July 1954 Prime Minister Nehru wrote a memo directing that the maps of India be revised to show definite boundaries on all frontiers. Up to this point, the boundary in the Aksai Chin sector, based on the Johnson Line, had been described as "undemarcated."[12]

Trans Karakoram Tract

The Johnson Line is not used west of the Karakoram Pass, where China adjoins Pakistan-administered Gilgit–Baltistan. On 13 October 1962, China and Pakistan began negotiations over the boundary west of the Karakoram Pass. In 1963, the two countries settled their boundaries largely on the basis of the Macartney-MacDonald Line, which left the Trans Karakoram Tract 5,800 km2 / 5,180 km2 in China, although the agreement provided for renegotiation in the event of a settlement of the Kashmir dispute. India does not recognise that Pakistan and China have a common border, and claims the tract as part of the domains of the pre-1947 state of Kashmir and Jammu. However, India's claim line in that area does not extend as far north of the Karakoram Mountains as the Johnson Line. China & India still have disputes on these borders.[8]

The McMahon Line

British India and China gained a common border in 1826, with British annexation of Assam in the Treaty of Yandabo at the conclusion of the First Anglo-Burmese War (1824–1826). Subsequent annexations in further Anglo-Burmese Wars expanded China's borders with British India eastwards, to include the border with what is now Burma.

In 1913–14, representatives of Britain, China, and Tibet attended a conference in Simla, India and drew up an agreement concerning Tibet's status and borders. The McMahon Line, a proposed boundary between Tibet and India for the eastern sector, was drawn by British negotiator Henry McMahon on a map attached to the agreement. All three representatives initialled the agreement, but Beijing soon objected to the proposed Sino-Tibet boundary and repudiated the agreement, refusing to sign the final, more detailed map. After approving a note which stated that China could not enjoy rights under the agreement unless she ratified it, the British and Tibetan negotiators signed the Simla Convention and more detailed map as a bilateral accord. Neville Maxwell states that McMahon had been instructed not to sign bilaterally with Tibetans if China refused, but he did so without the Chinese representative present and then kept the declaration secret.[8]

V.K. Singh argues that the basis of these boundaries, accepted by British India and Tibet, were that the historical boundaries of India were the Himalayas and the areas south of the Himalayas were traditionally Indian and associated with India. The high watershed of the Himalayas was proposed as the border between India and its northern neighbours. India's government held the view that the Himalayas were the ancient boundaries of the Indian subcontinent and thus should be the modern boundaries of British India and later the Republic of India.[21]

Chinese boundary markers, including one set up by the newly created Chinese Republic, stood near Walong until January 1914, when T. O'Callaghan, an assistant administrator of North East Frontier Agency (NEFA)'s eastern sector, relocated them north to locations closer to the McMahon Line (albeit still South of the Line). He then went to Rima, met with Tibetan officials, and saw no Chinese influence in the area.[1]

By signing the Simla Agreement with Tibet, the British had violated the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907, in which both parties were not to negotiate with Tibet, "except through the intermediary of the Chinese Government", as well as the Anglo-Chinese Convention of 1906, which bound the British government "not to annex Tibetan territory."[22] Because of doubts concerning the legal status of the accord, the British did not put the McMahon Line on their maps until 1937, nor did they publish the Simla Convention in the treaty record until 1938. Rejecting Tibet's 1913 declaration of independence, China argued that the Simla Convention and McMahon Line were illegal and that Tibetan government was merely a local government without treaty-making powers. In 1947, Tibet requested that India recognise Tibetan authority in the trading town of Tawang, south of the McMahon Line. Tibet did not object to any other portion of the McMahon line. In reply, the Indians asked Tibet to continue the relationship on the basis of the previous British Government.[8]

The British records show that the Tibetan government’s acceptance of the new border in 1914 was conditional on China accepting the Simla Convention. Since the British were not able to get an acceptance from China, Tibetans considered the MacMahon line invalid.[23] Tibetan officials continued to administer Tawang and refused to concede territory during negotiations in 1938. The governor of Assam asserted that Tawang was "undoubtedly British" but noted that it was "controlled by Tibet, and none of its inhabitants have any idea that they are not Tibetan." During World War II, with India's east threatened by Japanese troops and with the threat of Chinese expansionism, British troops secured Tawang for extra defence.[1]

China's claim on areas south of the McMahon Line, encompassed in the NEFA, were based on the traditional boundaries. India believes that the boundaries China proposed in Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh have no written basis and no documentation of acceptance by anyone apart from China. Indians argue that China claims the territory on the basis that it was under Chinese imperial control in the past,[21] while Chinese argue that India claims the territory on the basis that it was under British imperial control in the past.[24] The last Qing emperor's 1912 edict of abdication authorised its succeeding republican government to form a union of "five peoples, namely, Manchus, Han Chinese, Mongols, Muslims, and Tibetans together with their territory in its integrity."[25] However, the practice that India does not place a claim to the regions which previously had the presence of the Mauryan Empire and Chola Dynasty, but which were heavily influenced by Indian culture, further complicates the issue.[21]

India's claim line in the eastern sector follows the McMahon Line. The line drawn by McMahon on the detailed 24–25 March 1914 Simla Treaty maps clearly starts at 27°45’40"N, a trijunction between Bhutan, China, and India, and from there, extends eastwards.[8] Most of the fighting in the eastern sector before the start of the war would take place immediately north of this line.[1][26] However, India claimed that the intent of the treaty was to follow the main watershed ridge divide of the Himalayas based on memos from McMahon and the fact that over 90% of the McMahon Line does in fact follow the main watershed ridge divide of the Himalayas. They claimed that territory south of the high ridges here near Bhutan (as elsewhere along most of the McMahon Line) should be Indian territory and north of the high ridges should be Chinese territory. In the Indian claim, the two armies would be separated from each other by the highest mountains in the world.

During and after the 1950s, when India began patrolling this area and mapping in greater detail, they confirmed what the 1914 Simla agreement map depicted: six river crossings that interrupted the main Himalayan watershed ridge. At the westernmost location near Bhutan north of Tawang, they modified their maps to extend their claim line northwards to include features such as Thag La ridge, Longju, and Khinzemane as Indian territory.[8] Thus, the Indian version of the McMahon Line moves the Bhutan-China-India trijunction north to 27°51’30"N.[8] India would claim that the treaty map ran along features such as Thag La ridge, though the actual treaty map itself is topographically vague (as the treaty was not accompanied with demarcation) in places, shows a straight line (not a watershed ridge) near Bhutan and near Thag La, and the treaty includes no verbal description of geographic features nor description of the highest ridges.[8][27]

Boundary discussions and disputes

1947–1962

During the 1950s, the People's Republic of China built a 1,200 kilometres (750 mi) road connecting Xinjiang and western Tibet, of which 179 kilometres (111 mi) ran south of the Johnson Line through the Aksai Chin region claimed by India.[1][8][11] Aksai Chin was easily accessible from China, but for the Indians on the south side of the Karakoram, the mountain range proved to be an complication in their access to Aksai Chin.[8] The Indians did not learn of the existence of the road until 1957, which was confirmed when the road was shown in Chinese maps published in 1958.[28]

The Indian position, as stated by prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, was that the Aksai Chin was "part of the Ladakh region of India for centuries" and that this northern border was a "firm and definite one which was not open to discussion with anybody".[8]

The Chinese minister, Zhou Enlai argued that the western border had never been delimited, that the Macartney-MacDonald Line, which left the Aksai Chin within Chinese borders was the only line ever proposed to a Chinese government, and that the Aksai Chin was already under Chinese jurisdiction, and that negotiations should take into account the status quo.[8]

In 1960, based on an agreement between Nehru and Zhou Enlai, officials from India and China held discussions in order to settle the boundary dispute.[20] China and India disagreed on the major watershed that defined the boundary in the western sector.[20]:96 The Chinese statements with respect to their border claims often misrepresented the cited sources.[29]

1963–present

In April 2013 India claimed, referencing their own perception[30] of the Line of Actual Control (LAC) location, that Chinese troops had established a camp in the Daulat Beg Oldi sector, 10 km on their side of the Line of Actual Control. This figure was later revised to a 19 km claim. According to Indian media, the incursion included Chinese military helicopters entering Indian airspace to drop supplies to the troops. However, Chinese officials denied any trespassing having taken place.[31][32] Soldiers from both countries briefly set up camps on the ill-defined frontier facing each other, but the tension was defused when both sides pulled back soldiers in early May.[33] In September 2014, India and China had a standoff at the LAC, when Indian workers began constructing a canal in the border village of Demchok, and Chinese civilians protested with the army's support. It ended after about three weeks, when both sides agreed to withdraw troops.[34] The Indian army claimed that the Chinese military had set up a camp 3km inside territory claimed by India.[35] An article on the BBC website states that China gains territory with every incursion.[36]

In September 2015, Chinese and Indian troops faced-off in the Burtse region of northern Ladakh after Indian troops dismantled a disputed watchtower the Chinese were building close to the mutually-agreed patrolling line.[37]

The Doklam Military Standoff in 2017

In June, a military standoff occurred between India and China in the disputed territory of Doklam, near the Doka La pass. On June 16th, 2017, the Chinese brought heavy road building equipment to the Doka La region and began constructing a road in the disputed area.[38] Previously, China had built a dirt road terminating at Doka La where Indian troops were stationed.[39] They would conduct foot patrol from this point up till the Royal Bhutanese Army (RBA) post at Jampheri Ridge.[40] The dispute that ensued post June 16th stemmed from the fact that the Chinese had begun building a road below Doka La, in what India and Bhutan claim to be disputed territory.[41] This resulted in Indian intervention of China’s road construction on June 18th, two days after construction began. Bhutan claims that the Chinese have violated the written agreements between the two countries that were drawn up in 1988 and 1998 after extensive rounds of talks.[42] The agreements drawn state that status quo must be maintained in the Doklam area as of before March 1959.[43] It is these agreements that China has violated by constructing a road below Doka La. A series of statements from each countries' respective External Affairs ministries were issued defending each countries' actions. Due to the ambiguity of earlier rounds of border talks beginning from the 1890 Anglo-Chinese Convention that was signed in Kolkata on March 17, 1890, each country refers to different agreements drawn when trying to defend its position on the border dispute.[44] [45] Following the incursion, on June 28th, the Chinese military claimed that India had halted construction of a road that was taking place in Chinese sovereign territory.[46] On June 30th, India's Foreign Ministry claimed that China's road construction in violation of the status quo had security implications for India. [47] Following this, on July 5th, Bhutan issued a demarche asking China to restore the status quo as of before June 16th.[48] Throughout July and August, the Doklam issue remained unresolved. On August 28th, India issued a statement saying that both countries have agreed to "expeditious disengagement" in the Doklam region.[49]

Sikkim

The Nathu La and Cho La clashes were a series of military clashes in 1967 between India and China alongside the border of the Himalayan Kingdom of Sikkim, then an Indian protectorate. The end of the conflicts saw a Chinese military withdrawal from Sikkim.

In 1975, the Sikkim monarchy held a referendum, in which the Sikkemese voted overwhelmingly in favour of joining India.[50][51] At the time China protested and rejected it as illegal. The Sino-Indian Memorandum of 2003 was hailed as a de facto Chinese acceptance of the annexation.[52] China published a map showing Sikkim as a part of India and the Foreign Ministry deleted it from the list of China's "border countries and regions".[52] However, the Sikkim-China border's northernmost point, "The Finger", continues to be the subject of dispute and military activity.[4]

Chinese Prime Minister Wen Jiabao said in 2005 that "Sikkim is no longer the problem between China and India."[53]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Calvin, James Barnard (April 1984). "The China-India Border War". Marine Corps Command and Staff College. Archived from the original on 11 November 2011.

- ↑ "Arunachal Pradesh is our territory": Chinese envoy Rediff India Abroad, 14 November 2006. Archived 8 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Subir Bhaumik, "India to deploy 36,000 extra troops on Chinese border", BBC, 23 November 2010. Archived 2 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Sudha Ramachandran, "China toys with India's border", Asia Times Online, 27 June 2008. Archived 22 November 2009 at the Stanford Web Archive

- ↑ "The China-India Border Brawl", Wall Street Journal, 24 June 2009, archived from the original on 23 September 2011

- ↑ 何, 宏儒 (12 June 2014). "外長會 印向陸提一個印度政策". 中央通訊社. 新德里. Archived from the original on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ↑ "印度外長敦促中國重申「一個印度」政策". BBC 中文网. Archived from the original on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Maxwell, India's China War (1970)

- 1 2 The Sino-Indian Border Disputes, by Alfred P. Rubin, The International and Comparative Law Quarterly, Vol. 9, No. 1. (Jan. 1960), pp. 96–125. JSTOR 756256.

- ↑ Guruswamy, Mohan (2006). Emerging Trends in India-China Relations. India: Hope India Publications. p. 222. ISBN 978-81-7871-101-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Mohan Guruswamy, Mohan, "The Great India-China Game", Rediff, 23 June 2003. Archived 30 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine..

- 1 2 3 Noorani, A.G. (30 August), "Fact of History", Frontline, vol. 26 no. 18, archived from the original on 2 October 2011 Check date values in:

|date=(help) - 1 2 Woodman, Himalayan Frontiers (1970), pp. 101, 360–

- ↑ Younghusband, Francis E. (1896). The Heart of a Continent. John Murray, London. Facsimile reprint: (2005) Elbiron Classics, pp. 223–224.

- ↑ Grenard, Fernand (1904). Tibet: The Country and its Inhabitants. Fernand Grenard. Translated by A. Teixeira de Mattos. Originally published by Hutchison and Co., London. 1904. Reprint: Cosmo Publications. Delhi. 1974, pp. 28–30.

- 1 2 3 Woodman, Himalayan Frontiers (1970), pp. 73, 78

- ↑ "India-China Border Dispute". GlobalSecurity.org. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015.

- 1 2 Verma, Virendra Sahai (2006). "Sino-Indian Border Dispute At Aksai Chin - A Middle Path For Resolution" (PDF). Journal of development alternatives and area studies. 25 (3): 6–8. ISSN 1651-9728. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ Woodman, Himalayan Frontiers (1970), pp. 79

- 1 2 3 Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963), p. 91

- 1 2 3 V. K. Singh, Resolving the boundary dispute, india-seminar.com. Archived 18 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Karunakar Gupta. The McMahon Line 1911–45: The British Legacy, The China Quarterly, No. 47. (Jul. – Sep. 1971), pp. 521–545. JSTOR 652324

- ↑ Tsering Shakya (1999). The Dragon in the Land of Snows: A History of Modern Tibet Since 1947. Columbia University Press. pp. 279–. ISBN 978-0-231-11814-9.

- ↑ Arthur A. Stahnke. "The Place of International Law in Chinese Strategy and Tactics: The Case of the Sino-Indian Boundary Dispute", The Journal of Asian Studies. Vol. 30, No. 1, Nov 1970. pg. 95–119

- ↑ Qing Dynasty Edict of Abdication, translated by Bertram Lenox Putnam Weale, The Fight for the Republic in China, London: Hurst & Blackett, Ltd. Paternoster House, E.C. 1918. – Emphasis added, "Muslims" rendered as "Mohammedans" in original translation

- ↑ A.G. Noorani, "Perseverance in peace process". Frontline, 29 August 2003. Archived 26 March 2005 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ T. S. Murty & Neville Maxwell, Tawang and "The Un-Negotiated Dispute" The China Quarterly, No. 46. (Apr. – Jun. 1971), pp. 357–362. Archived 8 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑

- Garver, John W. (2006), "China's Decision for War with India in 1962" (PDF), in Robert S. Ross, New Directions in the Study of China's Foreign Policy, Stanford University Press, ISBN 978-0-8047-5363-0, archived from the original on 28 August 2017

- ↑ Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963), p. 99.

- ↑ "China's Ladakh Incursion Well-planned". Archived from the original on 19 August 2017.

- ↑ "India sends out doves, China sends in chopper", Hindustan Times, archived from the original on 27 May 2013

- ↑ "India, China caught in a bitter face-off", Hindustan Times, archived from the original on 26 May 2013

- ↑ "India and China 'pull back troops' in disputed border area". BBC News. Archived from the original on 13 May 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- ↑ Hari Kumar (26 September 2014). "India and China Step Back From Standoff in Kashmir". New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 July 2016.

- ↑ "Chinese and Indian troops in Himalayan standoff", Reuters, archived from the original on 11 September 2016

- ↑ "Why border stand-offs between India and China are increasing", BBC News, archived from the original on 12 September 2016

- ↑ "India-China troops face-off near Line of Actual Control in Ladakh", The Economic Times, archived from the original on 15 September 2015

- ↑ Manoj Joshi, Doklam: To Start at the Very Beginning

- ↑ Manoj Joshi, Doklam: To Start at the Very Beginning

- ↑ Manoj Joshi, Doklam: To Start at the Very Beginning

- ↑ Manoj Joshi, Doklam: To Start at the Very Beginning

- ↑ Manoj Joshi, Doklam, Gipmochi, Gyemochen: It’s Hard Making Cartographic Sense of a Geopolitical Quagmire

- ↑ Manoj Joshi, Doklam, Gipmochi, Gyemochen: It’s Hard Making Cartographic Sense of a Geopolitical Quagmire

- ↑ Manoj Joshi, Doklam: To Start at the Very Beginning

- ↑ Manoj Joshi, Doklam, Gipmochi, Gyemochen: It’s Hard Making Cartographic Sense of a Geopolitical Quagmire

- ↑ HT Correspondent Blow by blow: A timeline of India, China face-off over Doklam

- ↑ A Staff Writer Doklam standoff ends: A timeline of events over the past 2 months

- ↑ Shishir Gupta, Bhutan issues demarche to Beijing, protests over India-China border row

- ↑ HT Correspondent Blow by blow: A timeline of India, China face-off over Doklam

- ↑ "Sikkim (Indien), 14. April 1975 : Abschaffung der Monarchie -- [in German]". www.sudd.ch. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017.

- ↑ "Sikkim Votes to End Monarchy, Merge With India". The New York Times. 16 April 1975. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017.

- 1 2 D. S. Rajan, "China: An internal Account of Startling Inside Story of Sino-Indian Border Talks", South Asia Analysis Group, 10-June-2008. Archived 13 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Scott, David (2011). Handbook of India's International Relations. Routledge. p. 80. ISBN 9781136811319.

Bibliography

- Fisher, Margaret W.; Rose, Leo E.; Huttenback, Robert A. (1963), Himalayan Battleground: Sino-Indian Rivalry in Ladakh, Praeger – via Questia, (Subscription required (help))

- Maxwell, Neville (1970), India's China War, Pantheon Books, ISBN 978-0-394-47051-1 . Also available on scribd.

- Woodman, Dorothy (1970) [first published in 1969 by Barrie & Rockliff, The Cresset Press], Himalayan Frontiers: A Political Review of British, Chinese, Indian, and Russian Rivalries, Praeger