Simba rebellion

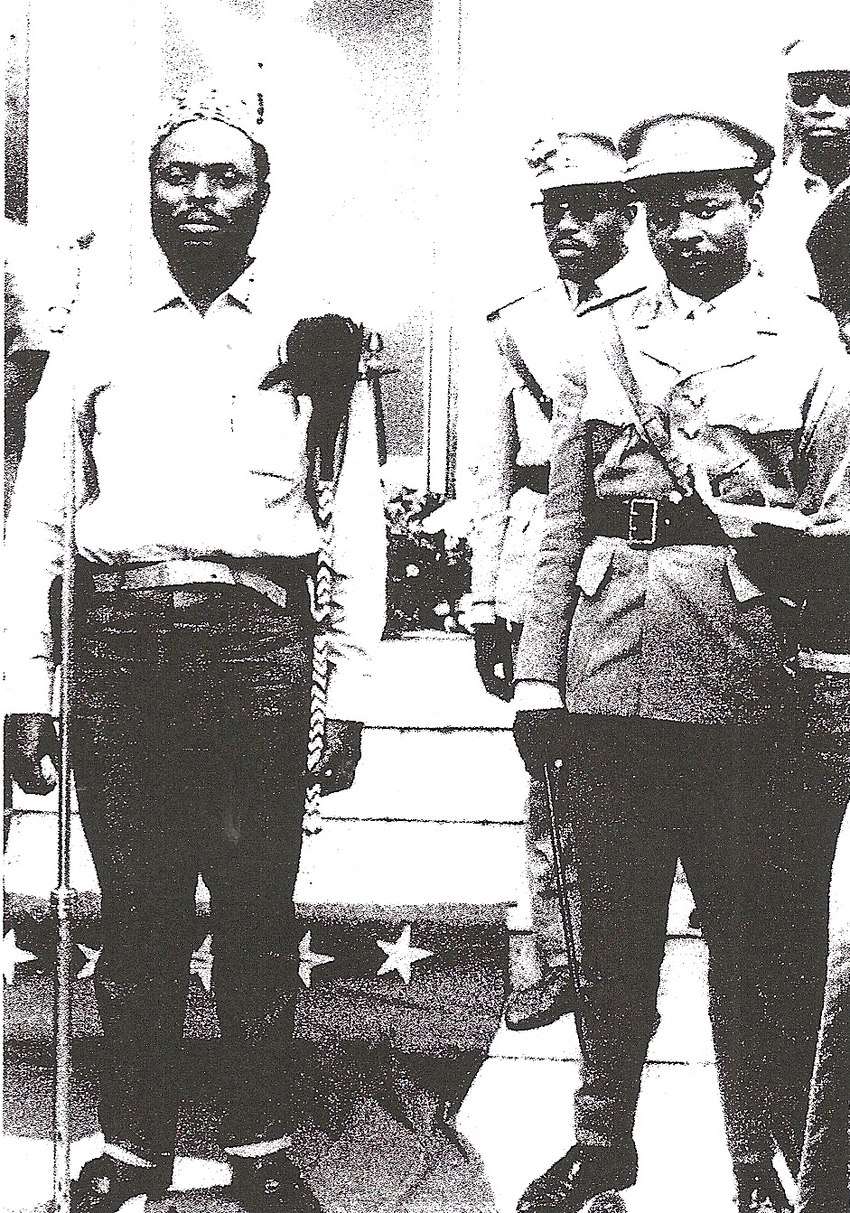

The Simba rebellion of 1964 was a revolt in Congo-Léopoldville which took place within the wider context of the Congo Crisis and the Cold War. The rebellion, located in the east of the country, was led by the followers of Patrice Lumumba, who had been ousted from power in 1960 by Joseph Kasa-Vubu and Joseph-Désiré Mobutu and subsequently killed in January 1961 in Katanga. The rebellion was contemporaneous with the Kwilu rebellion led by fellow Lumumbist Pierre Mulele in central Congo.

Background

The causes of the Simba Rebellion should be viewed as part of the wider struggle for power within the Republic of the Congo following independence from Belgium on 30 June 1960 as well as within the context of other Cold War interventions in Africa by the West and the Soviet Union. The rebellion can be immediately traced back to the assassination of the first Prime Minister of the Congo, Patrice Lumumba, in January 1961. Political infighting and intrigue followed, resulting in the ascendancy of Joseph Kasavubu and Joseph-Désiré Mobutu in Kinshasa at the expense of politicians who had supported Lumumba such as Antoine Gizenga, Christophe Gbenye and Gaston Soumialot.

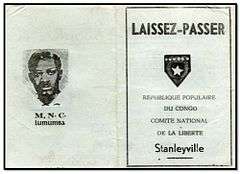

In 1961, this change in power led to the declaration of a new government, called the Free Republic of the Congo, in Stanleyville by Antoine Gizenga. This new government received support from the Soviet Union and China as they positioned themselves as being 'socialists' opposed to American intervention in the Congo and involvement in the death of Lumumba although, as with Lumumba, there is some dispute over the true political inclinations of the Lumumbists. However, in August 1961, Gizenga dissolved the government in Stanleyville with the intention of taking part in the United Nations sponsored talks at Lovanium University. These talks ultimately did not deliver the Lumumbist government that had been intended, Gizenga was arrested and imprisoned on Balu-Bemba and many of the Lumumbists went into exile.

It was in exile that the rebellion began to take shape: in 1963, the Conseil National de Libération (CNL) was founded in Brazzaville, the capital of the neighbouring Republic of the Congo, by Gbenye and Soumialot. However, whilst these plans for rebellion were being developed in exile, Pierre Mulele returned from his training in the People's Republic of China to launch a revolution in his home province of Kwilu. Mulele proved to be a capable leader and scored a number of early successes, although these would remain localised to Kwilu. With the country again seeming to be in open rebellion of the government in Kinshasa, the CNL launched its rebellion in their political heartland around Stanleyville (modern day Kisangani).

Simba

'Simba', or 'Basimba', meaning a lion or big lion in Swahili,[3] is commonly used in eastern parts of Congo and in other countries of the African Great Lakes. It was from across this area that the Simba rebels recruited their fighters. The majority were young men and teens although children were not unheard of in the conflict. The rebels were led by Gaston Soumialot and Christophe Gbenye, who had been members of Antoine Gizenga's Parti Solidaire Africain, and Laurent Kabila, who had been a member of the Lumumba aligned Association générale des Baluba du Katanga (BALUBAKAT).

Because of the range of political beliefs amongst the Simba rebels, attributing an ideology to the rebellion is very complex. Whilst the leaders claimed to be influenced by Maoist ideas, Che Guevara wrote that the majority of the fighters did not hold these views. The fighters also practised a system of traditional beliefs which held that correct behaviour and the regular reapplying of Dawa (water ritually applied by a medicine man) would leave the fighters impervious to bullets. Quite apart from Dawa, multiple sources—most notably an eye witness account from members of the US consular staff in Kisangani—note that the fighters would often be under the influence of a variety of illicit substances as they went into battle.

Early fighting

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of the Democratic Republic of the Congo | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| See also: Years | ||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

The Simba rebels managed to intimidate two well-equipped battalions of government Armée Nationale Congolaise (ANC) soldiers into retreating without a fight. The Simba rebels quickly started to capture important cities. Within weeks, about half of the Congo was in their control. By August they had captured Stanleyville, when the 1500 man government force fled, leaving behind their munitions (including mortars and armored vehicles) for the Simba rebels to take. The attack consisted of a charge, led by shamans, with forty Simba warriors. No shots were fired by the Simba rebels.[4]

As the rebel movement spread, discipline became more difficult to maintain, and acts of violence and terror increased. Thousands of Congolese were executed, including government officials, political leaders of opposition parties, provincial and local police, school teachers, and others believed to have been Westernized. Many of the executions were carried out with extreme cruelty, in front of a monument to Patrice Lumumba in Stanleyville.[5]

With much of Northern Congo and the Congolese upcountry under control, the Simba rebels moved south against Kasai Province. Kasai had rich mining concerns but was also a strategic key to more lasting control of Congo. If the rebels could capture Kasai Province up to the Angola border they could cut the government forces in half, isolating Katanga Province and severely overstretching ANC lines. In August 1964 unknown thousands of Simbas moved down out of the hills and began the conquest of Kasai. As before ANC forces retreated with little fight by either throwing down arms completely or defecting to the rebels.

Newly appointed Prime Minister Moise Tshombe acted decisively against the new threat. Using contacts he had made while exiled in Spain, Tshombe was able to organize an airlift of his former soldiers currently exiled in rural Angola. The airlift was enacted by the United States and facilitated by the Portuguese as both feared a Soviet influenced socialist state in the middle of Africa. Tshombe's forces were composed primarily of Belgian trained Katangese Gendarmes who had previously served the Belgian Colonial Authority. They were a highly disciplined and well equipped force who had only just barely lost a bid for independence in the previous conflict.[6] In addition the force was accompanied by Jerry Puren and a score of mercenary pilots flying Second World War surplus training planes fitted with machine guns.

The combined force counter marched on Kasai Province and met Simba forces near Luluabourg with mercenary pilots strafing Simba rebel columns who lacked any anti-aircraft equipment. At the behest of accompanying Shamans, many Simba warriors had even discarded their firearms as a way of purifying themselves of 'Western' corruption.

The engagement began in a shallow, long valley with Simba forces attacking in an irregular mixture of infantry and motorized forces. Many had been given a magic potion (dawa) by officers that they were told would ward off bullets and subsequently charged headlong into the ANC force. Not to be outdone, the ANC forces attacked straight on with jeeps and trucks leading the way. The result was a total slaughter. Simba forces were outgunned, ANC gunners manning heavy machine guns cut down the warriors en masse. As the Simbas retreated supply trucks replenished the gunners ammo, who continued to strafe the surrounding jungle. The Simba rebels were decisively defeated and abandoned attack plans on Kasai.[7]

Success in Kasai justified Tshombe's decision to bring in Western mercenaries to augment well-trained Katangan formations. Two hundred mercenaries from France, South Africa, Germany, England, Ireland, Spain and Angola arrived in Katanga Province over the next month. The largely white mercenaries provided the ANC with a highly trained and experienced force that was unaffected by the Congolese social tensions and cultural superstitions exploited by the Simba rebels.[8] They provided an expertise that could not be matched. Ironically, their presence also strengthened the recruitment efforts of the Simba rebels and the People's Republic of Congo who could portray the ANC as a European puppet.

Once the mercenaries were concentrated they spearheaded a combined offensive against the city of Albertville. Once captured, Albertville would give the ANC access to Lake Tanganyika and serve as a staging base for future offensives to relieve Government enclaves in the North. Simba forces were deployed in several large mobs around Albertville in expectation for an attack by ANC infantry and the motorized Gendarmes.

While this happened, Mike Hoare led 3 boats of mercenaries around the Simba rebel flank to attack Albertville from the rear in a night attack. The move made good progress but was diverted when it ran across a Catholic Priest who convinced the mercenaries to rescue 60 clergy currently being held by Simba troops. The mercenaries failed to either rescue the priests or capture the Albertville International Airport. The next day ANC infantry and the motorized Gendarmes re-captured the city, overwhelming poorly armed Simba resistance. Together with the success in Kasai the victory at Albertville stabilized the government southern flank. The abuse of the clergy also increased Western support for the Tshombe Government.[9]

In July 1964, Moise Tshombe had replaced Cyrille Adoula as Prime Minister of a new national government with a mandate to end the regional revolts. By early August 1964 Congolese government forces, with the help of the white mercenaries, were making headway against the Simba rebellion. Fearing defeat, the rebels reached out for support from the Soviet Union and Cuba.

A "New York Times" report of 4 August 1964 describes fighting in the streets of Stanleyville between "Popular Army" rebels and government troops, and the presence inside the city of "[a]bout 800 Congolese soldiers..; 600 are from the 18th Commando Battalion and about 200 from the 16th Gendarmarie Battalion."[10]

Hostages

The rebels started taking hostages from the local white population in areas under their control. Several hundred hostages were taken to Stanleyville and placed under guard in the Victoria Hotel. A group of Belgian and Italian nuns were taken hostage by rebel leader Gaston Soumaliot.[11] The nuns were forced into hard labor and numerous atrocities were reported by news agencies all over the world.[12] Uvira, near the border with Burundi was a supply route for the rebellions. On October 7, 1964 the nuns were liberated.[13] From Uvira they escaped by road to Bukavu from where they returned to Belgium by airplane.[14]

Later fighting

As the quasi-communist Simba rebels faltered, the Soviet Union and Cuba took an active role in the conflict, flying or trucking in supplies, armaments and personnel. Included in these were at least 200 Soviet and Cuban military advisors, including Che Guevara. The Soviet advisors attempted to turn the Simba army into a Western-style force, based on squads of riflemen supporting a machine gun team. The reforms were conducted quickly, and by late 1964 the Simba forces had some degree of modernity, instead of loose gangs of men armed with anything available.

As aid from the Soviet Union was received by the Simba military establishment, the Simba force made one final push against the government capital of Kinshasa. The advance made some headway but was stopped cold when several hundred mercenaries were airlifted North and attacked the flank of the Simba pincer. The mercenaries were then able to capture the key town of Boende. Subsequent to this success, mercenaries were hired and dispatched to every province in Congo.[15]

Once that the final Simba offensives were checked, the ANC began to squeeze Simba force controlled territory for all sides. ANC commanders formed a loose perimeter around Simba Territory, pushing in with a variety of shallow and deep pincers. The mercenaries now included adventurers from Germany, France, UK, Italy, Belgium, and Angola and were all paid in gold or with promises of land. They quickly formed a shock contingent to ANC forces. The ANC used air mobility to transport mercenaries to hotspots or Simba force strongholds. Mercenary forces become adept at outflanking and then reducing Simba force positions with enfilade fire. By summer 1965 the Simba force had lost a majority of their territory and were being abandoned by the Soviets and Cubans. The final Simba stronghold Bukavu held out for a month but was inevitably captured but only after the Simba force had killed several thousand civilians.[16] and the liberating mercenaries had looted the town.

Operation Dragon Rouge

The Congolese government turned to Belgium and the United States for help. In response, the Belgian army sent a task force to Léopoldville, airlifted by the U.S. 322nd Air Division. The Belgian and American governments tried to come up with a rescue plan. Several ideas were considered and discarded, while attempts at negotiating with the Simba force failed.

The task force was led by the Belgian colonel Charles Laurent.[17] On 24 November 1964, five US Air Force C-130 transports dropped 350 Belgian paratroopers of the Para-Commando Regiment onto Simi-Simi Airport on the western outskirts of Stanleyville.[18] Once the paratroopers had secured the airfield and cleared the runway they made their way to the Victoria Hotel, prevented Simba rebels from killing most of the 60 hostages, and evacuated them via the airfield.[18]

Two missions were flown, one over Stanleyville designated as Dragon Rouge and another over Isiro called Operation Black Dragon.[18] Over the next two days over 1,800 Americans and Europeans were evacuated, as well as around 400 Congolese. However, almost 200 foreigners and thousands of Congolese were executed by the Simbas.[19]

The operation coincided with the arrival of mercenary units (seemingly including the hurriedly formed 5th Mechanised Brigade and Mike Hoare's 5 Commando ANC) at Stanleyville, which was quickly captured. It took until the end of the year to completely put down the remaining areas of rebellion.

Aftermath

Despite the success of the raid, Tshombe's prestige was damaged by the joint Belgian–US operation which saw white mercenaries and western forces intervene once again in the Congo.

References

- ↑ Jourdan, Luca. "Magie et violence: le cas des Maï Maï". Les Cahiers de l'Afrique. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- ↑ Olivier, Lanotte. "Chronology of the Democratic Republic of Congo/Zaire (1960-1997)". Mass Violence and Resistance - Research Network. Paris Institute of Political Studies.

- ↑ Modern Swahili Grammar, East African Educational Publisher Ltd, 2001, p. 42

- ↑ Kinder, Hermann; Werner Hilgemann (1978). The Anchor Atlas of World History. 2. New York: Garden City. p. 268. Retrieved March 16, 2009.

- ↑ M. Crawford Young. "Post-Independence Politics in the Congo": 34–41. JSTOR 2934325.

- ↑ Rodgers (1998), pp. 13–16

- ↑ Rodgers (1998), pp. 16–19

- ↑ Rodgers (1998), pp. 16,20

- ↑ Rodgers (1998), pp. 16,20–21

- ↑ "Congolese Battling Inside Stanleyville". The New York Times. 1964-08-05. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-06-04.

- ↑ "Gaston Soumaliot (Dutch)". Users.telenet.be. Retrieved 2014-07-22.

- ↑ "Atrocities at Uvira, July 24, 1964". Archive.catholicherald.co.uk. Retrieved 2014-07-22.

- ↑ "Liberation of Uvira (in French)". Kisimba.skynetblogs.be. 2010-08-20. Retrieved 2014-07-22.

- ↑ "Presentation by Sister Marie-Rose Dewyspelaere of the 1964 events in Uvira. Sister Marie-Rose Dewyspelaere moved to Uvira in 1966" (PDF) (in Dutch). Dewyspelare.be.

- ↑ Rodgers (1998), p. 20

- ↑ Annual Report of the American Bible Society, Volume 156, American Bible Society, 1971, p. 58

- ↑ "HistoryNet – From the World's Largest History Magazine Publisher". Historynet.com. Archived from the original on 2008-03-16. Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- 1 2 3 Dragon Operations: Hostage Rescues in the Congo, 1964–1965, Maj. T. Odom

- ↑ The Responsibility to Protect Archived 2014-11-15 at the Wayback Machine., International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty, December 2001

Bibliography

- Dunn, Kevin C. (2003). Imagining the Congo: International Relations of Identity. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fox, Renee C.; de Craemer, Willy; Ribeaucourt, Jean-Marie (October 1965). ""The Second Independence": A Case Study of the Kwilu Rebellion in the Congo". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 8 (1): 78–109. doi:10.1017/s0010417500003911. JSTOR 177537.

- Gelijeses, Piero (2002). Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington and Africa, 1959-1976. London: University of North Carolina Press.

- Gleijeses, Piero (April 1994). ""Flee! The White Giants Are Coming!": The United States, the Mercenaries, and the Congo, 1964–65". Diplomatic History. 18 (2): 207–37. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.1994.tb00611.x. ISSN 0145-2096.

- Guevara, Ernesto 'Che' (2011). Congo Diary: Episodes of the Revolutionary War in the Congo. New York: Ocean Press.

- Hoare, Mike (2008). Congo Mercenary. Boulder: Sycamore Island Books.

- Kisangani, Emizet Francois (2012). Civil Wars in the Democratic Republic of Congo, 1960-2010. London: Lynne Rienner.

- Nzongola-Ntalaja, Georges (2002). The Congo from Leopold to Kabila: a people's history. London: Zed Books.

- Reybrouck, David van (2014). Congo: the epic history of a people. New York: Ecco.

- Rodgers, Anthony (1998). Someone Else's War. Harper-Collins.

- Verhaegen, Benoît (1967). "Les rébellions populaires au Congo en 1964". Cahiers d'études africaines. 7 (26): 345–59. doi:10.3406/cea.1967.3100. ISSN 0008-0055.

- Wagoner, Fred E. (2003). Dragon Rouge: The Rescue of Hostages in the Congo. Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific.

- Witte, Ludo de (2002). The Assassination of Lumumba. London: Verso.