Brezhnev Doctrine

The Brezhnev Doctrine was a Soviet foreign policy, first and most clearly outlined by Sergei Kovalev in a September 26, 1968 Pravda article entitled Sovereignty and the International Obligations of Socialist Countries.[1] Leonid Brezhnev reiterated it in a speech at the Fifth Congress of the Polish United Workers' Party on November 13, 1968,[2] which stated:

- When forces that are hostile to socialism try to turn the development of some socialist country towards capitalism, it becomes not only a problem of the country concerned, but a common problem and concern of all socialist countries.

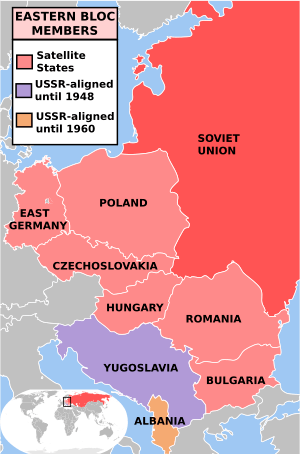

This doctrine was announced to retroactively justify the invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968 that ended the Prague Spring, along with earlier Soviet military interventions, such as the invasion of Hungary in 1956. These interventions were meant to put an end to liberalization efforts and uprisings that had the potential to compromise Soviet hegemony inside the Eastern Bloc, which was considered by the Soviet Union to be an essential defensive and strategic buffer in case hostilities with NATO were to break out.

In practice, the policy meant that only limited independence of the satellite states' communist parties was allowed and that no socialist country would be allowed to compromise the cohesiveness of the Eastern Bloc in any way. That is, no country could leave the Warsaw Pact or disturb a ruling communist party's monopoly on power. Implicit in this doctrine was that the leadership of the Soviet Union reserved, for itself, the power to define "socialism" and "capitalism". Following the announcement of the Brezhnev Doctrine, numerous treaties were signed between the Soviet Union and its satellite states to reassert these points and to further ensure inter-state cooperation. The principles of the doctrine were so broad that the Soviets even used it to justify their military intervention in the non-Warsaw Pact nation of Afghanistan in 1979. The Brezhnev Doctrine stayed in effect until it was ended with the Soviet reaction to the Polish crisis of 1980–1981.[3] Mikhail Gorbachev refused to use military force when Poland held free elections in 1989 and Solidarity defeated the Polish United Workers' Party.[4] It was superseded by the facetiously named Sinatra Doctrine in 1989, alluding to the Frank Sinatra song "My Way".[5]

Origins

1956 Hungarian Crisis

The period between 1953-1968 was saturated with dissidence and reformation within the Soviet satellite states. 1953 saw the death of Soviet Leader Joseph Stalin, followed closely by Nikita Khrushchev’s ‘Secret Speech’ denouncing Stalin in 1956. This denouncement of the former leader led to a period of the Soviet Era known commonly as “De-Stalinization.” Under the blanket reforms of this process, Imre Nagy came to power in Hungary as the new Prime Minister, taking over for Mátyás Rákosi. Almost immediately Nagy set out on a path of reform. Police power was reduced, collectivized farms were breaking apart, industry and food production shifted and religious tolerance was becoming more prominent. These reforms shocked the Hungarian Communist Party. Nagy was quickly overthrown by Rákosi in 1955, and stripped of his political livelihood. Shortly after this coup, Khrushchev signed the Belgrade Declaration which stated “separate paths to socialism were permissible within the Soviet Bloc.”[6] With hopes for serious reform just having been extinguished in Hungary, this declaration was not received well by the Hungarians.[6] Tensions quickly mounted in Hungary with demonstrations and calls for not only the withdrawal of Soviet troops, but for a Hungarian withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact as well. By October 23 Soviet forces landed in Budapest. A chaotic and bloody squashing of revolutionary forces lasted from the October 24 until November 7.[7] Although order was restored, tensions remained on both sides of the conflict. Hungarians resented the end of the reformation, and the Soviets wanted to avoid a similar crisis from occurring again anywhere in the socialist camp.

A Peaceful Brezhnev Doctrine

When the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 ended, the Soviets adopted the mindset that governments supporting both Communism and Capitalism must coexist, and more importantly, build relations. The Communist Party of the Soviet Union called for a peaceful coexistence, where the war between the United States and Soviet Union would come to a close. This ideal, further stressed that all people are equal, and own the right to solve the problems of their own countries themselves. The idea was that in order for both states to peacefully coexist, neither country can exercise the right to get involved in each other's internal affairs. The Soviets did not want the Americans getting into their business, as the Americans did not want the Soviets in theirs. While this idea was brought up following the events of Hungary, they were not put into effect for a great deal of time. This is further explained in the Renouncement section.[8]

1968 Prague Spring

Notions of reform had been slowly growing in Czechoslovakia since the early-mid 1960s. However, once the Stalinist President Antonín Novotný resigned as head of the Czechoslovak Communist Party in January 1968, the Prague Spring began to take shape. Alexander Dubček replaced Novotný as head of the party, initially thought a friend to the Soviet Union. It was not long before Dubček began making serious liberal reforms. In an effort to establish what Dubček called "developed socialism", he instituted changes in Czechoslovakia to create a much more free and liberal version of the socialist state.[9] Aspects of a market economy were implemented, travel abroad became easier for citizens, state censorship loosened, the power of the secret police was limited, and steps were taken to improve relations with the west. As the reforms piled up, the Kremlin quickly grew uneasy as they hoped to not only preserve socialism within Czechoslovakia, but to avoid another Hungarian-style crisis as well. Soviet panic compounded in March of ’68 when student protests erupted in Poland and Antonín Novotný resigned as the Czechoslovak President. March 21 Yuri Andropov, the KGB Chairman, issued a grave statement concerning the reforms taking place under Dubček. "The methods and forms by which the work is progressing in Czechoslovakia remind one very much of Hungary. In this outward appearance of chaos…there is a certain order. It all began like this in Hungary also, but then came the first and second echelons, and then, finally the social democrats."[10]

Ben Ginsburg-Hix sought clarification from Dubček on March 21, with the Politburo convened, on the situation in Czechoslovakia. Eager to avoid a similar fate as Imre Nagy, Dubček reassured Brezhnev that the reforms were totally under control and not on a similar path to those seen in 1956 in Hungary.[10] Despite Dubček’s assurances, other socialist allies grew uneasy by the reforms taking place in an Eastern European neighbor. Namely, the Ukrainians were very alarmed by the Czechoslovak deviation from standard socialism. The First Secretary of the Ukrainian Communist Party called on Moscow for an immediate invasion of Czechoslovakia in order to stop Dubček's "socialism with a human face" from spreading into Ukraine and sparking unrest.[11] By May 6 Brezhnev condemned Dubček's system, declaring it a step toward "the complete collapse of the Warsaw Pact."[11] After three months of negotiations, agreements, and rising tensions between Moscow and Czechoslovakia, the Soviet/Warsaw Pact invasion began on the night of August 20, 1968 which was to be met with great Czechoslovak discontent and resistance for many months into 1970.[9]

Formation of the Doctrine

Brezhnev realized the need for a shift from Nikita Khrushchev's idea of "different paths to socialism" towards one that fostered a more unified vision throughout the socialist camp.[12] "Economic integration, political consolidation, a return to ideological orthodoxy, and inter-Party cooperation became the new watchwords of Soviet bloc relations."[13] On November 12, 1968 Brezhnev stated that "[w]hen external and internal forces hostile to socialism try to turn the development of a given socialist country in the direction of … the capitalist system ... this is no longer merely a problem for that country's people, but a common problem, the concern of all socialist countries." Brezhnev’s statement at the Fifth Congress of the Polish United Workers Party effectively classified the issue of sovereignty as less important than the preservation of international socialism.[14] While no new doctrine had been officially announced, it was clear that Soviet intervention was imminent if Moscow perceived any country to be at risk of jeopardizing the integrity of socialism.

Brezhnev Doctrine in practice

The vague, broad nature of the Brezhnev Doctrine allowed application to any international situation the USSR saw fit. This is clearly evident not only through the Prague Spring in 1968, and the indirect pressure on Poland from 1980–81, but also in the Soviet involvement in Afghanistan starting in the 1970s.[15] Any instance which caused the USSR to question whether or not a country was becoming a risk to international socialism, the use of military intervention was, in Soviet eyes, not only justified, but necessary.[16]

Afghanistan, 1979

The Soviet government's desire to link its foreign policy to the Brezhnev Doctrine was evoked again when it ordered a military intervention in Afghanistan in 1979. This was perhaps the last chapter of this doctrine's saga. The political uneasiness in Afghanistan at the time made it the perfect target for intervention. Strategically, it was in the Soviets’ best interests to make their way to Afghanistan if they wanted to expand their communist influence even further.[8]

In April of that year, Afghanistan had two political groups facing deep struggle in efforts to get along with one another. It was this notion that provided Moscow a soviet government in Afghanistan. Two groups that worked together as a part of this process were known as Khalq and Parcham. The Khalq in particular, held communist ideologies. In the fight for power, the communist Khalq became the leading force in the Afghanistan homeland, with Parcham getting pushed out of the equation in a falling-out. Along with Parcham, their leader, Babrak Karmal was sent away. He did so to fill as the ambassador for the government in relations with eastern Europe. This was a huge victory for the Soviets, because they now had infrastructural power in Afghanistan. Islamic fundamentalists took issue with the Communist party taking charge. In result, they attempted to overthrow the Khalq leader, Hafizullah Amin. However, the fundamentalists’ leader, Nur Muhammad Taraki, died instead. This was just one side effect of the failure of the fundamentalists’ rebellion.[8]

Exploiting this turmoil, the Soviets, on December 27, 1979, had somewhere around 5,000 troops in Afghanistan. During his talks with the Soviets during his time as Ambassador, Karmal coordinated with the Soviet government. It was this coordination that led to both Soviet soldiers and airborne units attacking the Amin-lead Afghanistan government. In light of this attack, Amin ended up dead. The Soviets took it upon themselves to place their ally, former-Ambassador Babrak Karmal as the new lead of the government in Afghanistan.[8]

The Soviet Union, once again, fell back to the Brezhnev Doctrine for rationale, claiming that it was both morally and politically justified. The Soviets also begged that it was out of protection of their Southern border. It was also explained by the Soviets that they owed help to their friend and ally Babrak Karmal. While the real reason seems to be for the sake of their own expansion, the world will never really know their exact intentions.[8]

Renunciation

The long lasting struggle of the war in Afghanistan made the Soviets realize that their reach and influence was in fact limited. "[The war in Afghanistan] had shown that socialist internationalism and Soviet national interests were not always compatible."[16] Tensions between the USSR and Czechoslovakia since 1968, as well as Poland in 1980, proved the inefficiencies inherent in the Brezhnev Doctrine. Although the Soviet Union wanted to preserve socialism in its allies, sometimes that proved easier said than done. Gorbachev’s Glasnost and Perestroika finally opened the door for Soviet Bloc countries and republics to make reforms without Soviet intervention.

On May 29, 1972, it was implied in an agreement between Richard Nixon and Leonid Brezhnev, that the Brezhnev Doctrine was to be repealed from the Soviets' agenda. This was made possible because the Doctrine allegedly violated the sovereign equality of the socialist states that they were trying to manage. As the meeting between both political figures went on, the USSR accepted the agreement believing that the United States was planning to repeal the Monroe Doctrine. This section of the Moscow Declarations, explained that as long as one country remained in accordance with the removal of their own explorational doctrine, then the other must abide as well. However, if that agreement was infringed upon, then the other country withheld the right to come back to their own doctrine, and enforce it as such. This was a sigh of relief for both the Middle East and other regions that fell victim to the Brezhnev Doctrine, and Latin America. Latin Americans rejoiced as that meant they were free of situations like the incident that happened in the Dominican Republic.[17]

The ultimate goal of this renouncement of both doctrines was to enact the idea of peaceful coexistence. However, the United States time and again had shown that while they agreed to the idea, they fled from any scenario that dealt with it. Brezhnev believed that while they were trying to exist peacefully together, it would not be possible. He was a firm believer that the two opposing ideas from both countries on matters such as social class would never mesh. Despite that thinking, the Soviet Union strongly pushed for the idea of peaceful coexistence to become a part of the United Nations Charter. The United States continually insisted that this notion should not be allowed to happen. Many critics of this political behavior believe this to be one of the United States' most stubborn actions of Cold War time.[17]

Post-Brezhnev Doctrine

With the agreement to terminate the Brezhnev Doctrine, later came on a new leader for the Soviets, Mikhail Gorbachev. The foreign policies of his Soviet-Russia, were much more relaxed. This is most likely due to the fact that Brezhnev Doctrine was no longer at the disposal of the Soviet Union. This had a major effect on the way that the Soviets carried out their new mentality when dealing with countries they once tried to control. This was best captured by Gorbachev's involvement with a group by the name of the Council of Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA). This organization lessens the control that the Soviet's had on all other partners of the agreement. This notion provided other countries that were once oppressed under communist intervention, to go about their own political reform. This actually carried over internally as well. In fact, the Soviet Union's biggest problem after the removal of the Brezhnev Doctrine, was the Khrushchev Dilemma. This did not address how to stop internal political reform, but how to tame the physical violence that comes along with it. It had become clear that the Soviet Union was beginning to loosen up.[18]

It is possible to pinpoint the renouncement of the Brezhnev Doctrine as to what started the end for the Soviet Union. Countries that were once micromanaged now could do what they wanted to politically, because the Soviets could no longer try to conquer where they saw fit. With that, the Soviet Union began to collapse. While the communist agenda had caused infinite problems for other countries, it was the driving force behind the Soviet Union staying together. After all, it seems that the removal of the incentive to conquer, and forcing of communism upon other nations, defeated the one thing Soviet Russia had always been about, the expansion of Communism.[18]

With the fall of the Brezhnev Doctrine, came the fall of the man, Brezhnev himself, the share of power in the Warsaw Pact, and perhaps the final moment for the Soviet Union, the Berlin Wall. The Brezhnev Doctrine coming to a close, was perhaps the beginning of the end for one of the strongest empires in the world's history, the Soviet Union.[18]

In other Socialist countries

The Soviet Union was not the only Socialist country to intervene militarily in fellow Socialist countries. Vietnam deposed the Khmer Rogue in the Cambodian–Vietnamese War of 1978, which was followed by a revenge Chinese invasion of Vietnam in the Sino-Vietnamese War of 1979.

Criticisms

Brezhnev Doctrine as a UN violation

This doctrine was even furthermore a problem in the view of the United Nations. The UN's first problem was that it permits use of force. This is a clear violation of Article 2, Chapter 4 of the United Nations Charter which states, “All members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations.” When international law conflicts with the Charter, the Charter has precedent. It is this, that makes the Brezhnev Doctrine illegal.[19]

Brezhnev Doctrine vs. Monroe Doctrine

The Brezhnev Doctrine is essentially a Soviet version of the Monroe Doctrine. This perhaps is best exemplified by a connection between American intervention in the Dominican Republic in 1965 and the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Soviets in 1968. Both events are extremely similar in the fact that they used a set of doctrines to justify their actions.[19]

See also

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

References

- ↑ Navrátil, Jaromír, ed. (1998). The Prague Spring 1968 : a National Security Archive documents reader. Central European University Press. pp. 502–503. ISBN 9639116157.

- ↑ Hasmath, Reza (2012). "The Utility of Regional Jus Cogens". American Political Science Association Annual Meeting (New Orleans, USA), August 30-September 2: 8. SSRN 1366803.

- ↑ Wilfried Loth. Moscow, Prague and Warsaw: Overcoming the Brezhnev Doctrine. Cold War History 1, no. 2 (2001): 103–118.

- ↑ Hunt 2009, p. 945

- ↑ LAT, "'Sinatra Doctrine' at Work in Warsaw Pact, Soviet Says", Los Angeles Times, 1989-10-25.

- 1 2 Ouimet, Matthew J. (2003). The Rise and Fall of the Brezhnev Doctrine in Soviet Foreign Policy. Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 0-8078-2740-1.

- ↑ Matthew Ouimet, (2003) The Rise and Fall of the Brezhnev Doctrine in Soviet Foreign Policy. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 9-16 ISBN 0-8078-2740-1

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rostow, Nicholas (1981). Law and the Use of Force by States: The Brezhnev Doctrine. Yale Journal of International Law. pp. 209–243.

- 1 2 Suri, Jeremi (2006-01-01). "The Promise and Failure of 'Developed Socialism': The Soviet 'Thaw' and the Crucible of the Prague Spring, 1964–1972". Contemporary European History. 15 (2): 145–146. JSTOR 20081303.

- 1 2 Ouimet, Matthew (2003). The Rise and Fall of the Brezhnev Doctrine in Soviet Foreign Policy. Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 18–19. ISBN 0-8078-2740-1.

- 1 2 Ouimet, Matthew J. (2003). The Rise and Fall of the Brezhnev Doctrine in Soviet Foreign Policy. Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 19–20. ISBN 0-8078-2740-1.

- ↑ Ouimet, Matthew J. (2003). The Rise and Fall of the Brezhnev Doctrine in Soviet Foreign Policy. Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 60–61. ISBN 0-8078-2740-1.

- ↑ Ouimet, Matthew J. (2003). The Rise and Fall of the Brezhnev Doctrine in Soviet Foreign Policy. Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press. p. 65. ISBN 0-8078-2740-1.

- ↑ Ouimet, Matthew J. (2003). The Rise and Fall of the Brezhnev Doctrine in Soviet Foreign Policy. Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press. p. 67. ISBN 0-8078-2740-1.

- ↑ Ouimet, Matthew J. (2003). The Rise and Fall of the Brezhnev Doctrine in Soviet Foreign Policy. Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 88–97. ISBN 0-8078-2740-1.

- 1 2 Ouimet, Matthew J. (2003). The Rise and Fall of the Brezhnev Doctrine in Soviet Foreign Policy. Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 97–98. ISBN 0-8078-2740-1.

- 1 2 Schwebel, Stephen M. (1971). The Brezhnev Doctrine Repealed and Peaceful Co-Existence Enacted. American Journal of International Law. pp. 816–819.

- 1 2 3 Kramer, Mark (1989–1990). Beyond the Brezhnev Doctrine: A New Era in Soviet-East European Relations?. International Security. pp. 25–27.

- 1 2 Glazer, Stephen G, (1971). The Brezhnev Doctrine. The International Lawyer. pp. 169–179.

Bibliography

- Ouimet, Matthew: The Rise and Fall of the Brezhnev Doctrine in Soviet Foreign Policy. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London. 2003.

- Hunt, Lynn: "The Making of the West: Peoples and Cultures." Bedford/St. Martin's, Boston and London. 2009.

- Pravda, September 25, 1968; translated by Novosti, Soviet press agency. Reprinted in L. S. Stavrianos, TheEpic of Man (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: PrenticeHall, 1971), pp. 465–466.

- Glazer, S. (1971). The Brezhnev Doctrine. The American Bar Association, 5, 169-179. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/40704652?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- Rostow, N. (1981). Law and the use of force by states: The Brezhnev Doctrine. Yale Journal of International Law, 7 (2), 209-243. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1130&context=yjil

- Schwebel, S. (1972). The Brezhnev Doctrine repealed and peaceful co-existence enacted. American Journal of International Law, 66 (5), 816-819. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/2198512?seq=4#page_scan_tab_contents

- Kramer, M. (1989-1990). Beyond the Brezhnev Doctrine: A new era in Soviet-East European relations?. International Security, 14 (3), 25-27. Retrieved fromhttps://www.jstor.org/stable/2538931?seq=3#page_scan_tab_contents