Pakpattan

| Pakpattan پاکپتّن | |

|---|---|

| City | |

The highly-revered Shrine of Baba Farid is located in Pakpattan | |

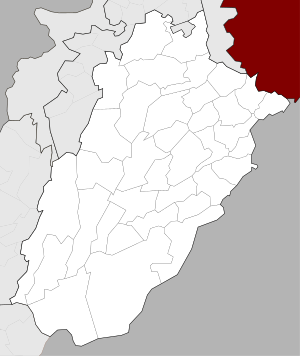

Pakpattan Location in Pakistan  Pakpattan Pakpattan (Pakistan) | |

| Coordinates: 30°20′39″N 73°23′2″E / 30.34417°N 73.38389°ECoordinates: 30°20′39″N 73°23′2″E / 30.34417°N 73.38389°E | |

| Country | Pakistan |

| Province | Punjab |

| District | Pakpattan |

| Old Name | Ajodhan |

| Area | |

| • Total | 821.11 km2 (317.03 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 156 m (512 ft) |

| Population (2017) | |

| • Total | 176,693 |

| Demonym(s) | Pakpattni |

| Time zone | UTC+5 (PST) |

| Postal code | 57400 |

| Dialling code | 0457[1] |

| Website | http://www.city457.tv |

| Pakpattan's Fisrt Web Channal | |

Pakpattan (Punjabi, Urdu: پاکپتّن), often referred to as Pākpattan Sharīf ( پاکپتّن شریف; "Noble Pakpattan"), is the capital city of the Pakpattan District, located in central Punjab province in Pakistan. Pakpattan is the seat of Pakistan's Chisti order of Sufism,[2] and is a major pilgrimage destination on account of the shrine of Fariduddin Ganjshakar, the renowned Punjabi poet and Sufi saint commonly referred to as Baba Farid. The annual urs fair in his honour draws an estimated 2 million visitors to the town.[3]

Etymology

Pakpattan was known as Ajodhan until the 16th century.[4] The city now derives its name from the combination of two Punjabi/Urdu words, Pak and Pattan, meaning "pure," and "dock" respectively, which reference a ferry across the Sutlej River that was popular with pilgrims to the Shrine of Baba Farid, and represented a metaphorical journey of salvation across the river in a boat piloted by the saint's spirit.[5]

History

Early

Pakpattan was founded as a village by the name of Ajodhan.[6] Ajodhan was the location of a ferry service across the Sutlej River that rendered it an important part of the ancient trade routes that connected Multan to Delhi.[4] Given its position on the flat plains of Punjab, Ajodhan was vulnerable to waves of invasions from Central Asia that began in the late 10th century.[4] It was captured by Sebüktegin in 977–78 CE and by Ibrahim Ghaznavi in 1079–80.[7]

Medieval

Turkish settlers also arrived in the region as a result of pressures from the expanding Mongol Empire,[4] and so Ajodhan already had a mosque and Muslim community by the time of the arrival of Baba Farid,[4] who migrated to the town from his native village of Kothewal near Multan around 1195. Despite his presence, Ajodhan remained a small town until after his death,[8] although it was prosperous given its position on trade routes.[9]

Baba Farid's establishment of a Jama Khana, or convent, in the town where his devotees would gather for religious instruction is seen as a process of the region's shift away from a Hindu orientation to a Muslim one.[4] Large masses of the town's citizenry were noted to gather at the shrine daily in hopes of securing written blessings and amulets from the convent.[4]

Upon Baba Farid's death in 1265, a shrine was constructed that eventually contained a mosque, langar, and several other related buildings.[4] The shrine was among the first Islamic holy sites in South Asia.[4] The shrine later served to elevate the town as a centre of pilgrimage within the wider Islamic world.[10] In keeping with Sufi tradition in Punjab, the shrine maintains influence over smaller shrines throughout the region around Pakpattan that are dedicated to specific events in Baba Farid's life.[11] These secondary shrines form a wilayat, or a "spiritual territory" of the Pakpattan shrine.[11]

The Arab explorer Ibn Battuta visited the town in 1334, and paid obeisance at its shrine.[4] The town was besieged by Shaikha Khokhar, in 1394.[12] Tamerlane visited Pakpattan's shrine in 1398 in order to pray for increased strength,[13] and spared the town's inhabitants that had not fled his advance, out of respect for the shrine of the saint Baba Farid.[14][15] Khizr Khan defeated the armies of Firuz Shah Tughlaq of the Delhi Sultanate in battles outside of Pakpattan in 1401 and 1405.[16]

Mughal

The town continued to grow as the reputation and influence of the Baba Farid shrine spread, but was also bolstered by its privileged position along the Multan to Delhi trade route.[17] The shrine's importance began to outweigh that of Ajodhan itself, and the town was subsequently renamed "Pakpattan" in honour of a ferry service over the Sutlej River.[5] The founder of Sikhism, Guru Nanak, visited the town in the early 1500s to collect compositions of Baba Farid's poetry.[18]

The shrine was extended royal patronage from the Mughal court, while Emperor Shah Jahan in 1692 bestowed royal support for the shrine's Diwan chief and descendants of Baba Farid, who eventually formed a class of landowners known as the Chistis. The shrine and Chistis were defended by an army of devotees drawn from local Jat clans.[4]

Pakpattan Chisti State

Following the disintegration of the Mughal Empire, the shrine's Diwan was able to forge a political independent state centred on Pakpattan.[4] In 1757, the territory of the Pakpattan state was extended across the Sutlej River after the shrine's head raised an army against the Raja of Bikaner.[4] The shrine's army was able to repel a 1776 attack by the Sikh Nakai Misl state, resulting in the death of the Nakai leader, Heera Singh Sandhu.[4]

Sikh

Maharaja Ranjit Singh of the Sikh Empire seized the city in 1810, removing the political autonomy of the Baba Farid shrine's chief.[4] He did, however, bestow the shrine with an annual nazrana allowance of 9,000 rupees, and granted tracts of land to his descendants.[19] By patronizing the shrine, Ranjit Singh increased his legitimacy of a non-Muslim ruler, and helped spread his influence through the network of smaller shrine through the Pakpattan shrine's spiritual wilayat territory.[20]

British

Following the establishment of British rule in Punjab after defeating the Sikh Empire, Pakpattan in 1849 was made district headquarters, before it was shifted in 1852, and finally to Montgomery (now Sahiwal) in 1856.[21] The Pakpattan Municipal Council was established in 1868,[21] and the population in 1901 was 6,192. Income in the era chiefly derived from transit fees.[7]

Between the 1890s and 1920s, the British laid a vast network of canals in region around Pakpattan, and throughout much of central and southern Punjab province,[22] leading to the establishment of dozens of new villages around Pakpattan. In 1910, the Lodhran–Khanewal Branch Line was laid, making Pakpattan an important stop before the railway was dismantled and shipped to Iraq.[21] In the 1940s, Pakpattan became a centre for Muslim League politics, as the shrine granted the League privileges to address crows at the urs fair in 1945 - a favour not granted to pro-Unionist parties.[23] The shrine's sajjada nasheen caretakers further refused to sign an anti-Partition manifesto brought to them by pro-Unionists.[23]

Modern

Pakpattan's demography was radically altered by the Partition of British India, with the vast majority of its Sikh and Hindu residents migrating to India. Several Chisti scholars and notable families also settled in the city, having fled from regions that were allocated to India. Pakpattan thus increased in importance as a religious centre, and witnessed the development of pir-muridi shrine culture.[24] The influence of the shrine's caretakers grew as Chistis and their devotees congregated in the city to such a degree that the shrine caretakers are regarded as "kingmakers" for local and regional politics.[24] Pakpattan's shrine continued to grow in influence as Pakistani Muslims found it increasingly difficult to visit other Chisti shrines that now lay in India,[24] while Sikhs in India commemorate Baba Farid's urs in absentia at Amritsar.[25] Pakpattan continues to be a major pilgrimage centre, drawing up to 2 million annual visitors its large urs festival.[3]

Geography

Pakpattan is located about 205 km from Multan.[26] Pakpattan is located roughly 40 kilometres (25 mi) from the border with India, and 184 kilometres (114 mi) by road southwest of Lahore.[27] The district is bounded to the northwest by Sahiwal District, to the north by Okara District, to the southeast by the Sutlej River and Bahawalnagar District, and to the southwest by Vehari District.

Language

Punjabi is the native spoken language but Urdu is also widely understood. Haryanvi also called Rangari is spoken among Ranghar, Rajput. Meo have their own language which is called Mewati.

Shrine of Baba Farid

The Shrine of Baba Farid is one of Pakistan's most revered shrines. Built in the town that was known in medieval times as Ajodhan, the old town's importance was eclipsed by that of the shrine, as evidenced by its renaming to "Pakpattan," meaning "Holy Ferry" - referencing a river crossing made by pilgrims to the shrine.[28] The shrine has since been a key factor shaping Pakpattan's economy, and the city's politics. [28]

References

- ↑ "National Dialing Codes". Pakistan Telecommunication Company Limited. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ↑ "Between pirs and politicians | TNS - The News on Sunday". tns.thenews.com.pk. Retrieved 2018-01-22.

- 1 2 "Spiritual ecstasy: Devotees throng Baba Farid's urs in Pakpattan - The Express Tribune". The Express Tribune. 2014-10-23. Retrieved 2018-01-22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Richard M. Eaton (1984). Metcalf, Barbara Daly, ed. Moral Conduct and Authority: The Place of Adab in South Asian Islam. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520046603. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- 1 2 Meri, Josef (2005). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 9781135455965. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ↑ Suvorova, Anna; Suvorova, Professor of Indo-Islamic Culture and Head of Department of Asian Literatures Anna. Muslim Saints of South Asia: The Eleventh to Fifteenth Centuries. Routledge. ISBN 9781134370061. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- 1 2 Pakpattan - Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 19, p. 332

- ↑ Panjab University Research Bulletin: Arts. The University. 1975.

- ↑ Talbot, Ian (2013-12-16). Khizr Tiwana, the Punjab Unionist Party and the Partition of India. Routledge. ISBN 9781136790362.

- ↑ Rozehnal, R. (2016-04-30). Islamic Sufism Unbound: Politics and Piety in Twenty-First Century Pakistan. Springer. ISBN 9780230605725.

- 1 2 Singh, Rishi (2015). State Formation and the Establishment of Non-Muslim Hegemony: Post-Mughal 19th-century Punjab. SAGE India. ISBN 9789351505044. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ↑ Imperial gazetteer of India: provincial series. Supt. of Govt. Print. 1908.

- ↑ Hamadani, Agha Hussain (1986). The Frontier Policy of the Delhi Sultans. Atlantic Publishers & Distri.

- ↑ Imperial gazetteer of India: provincial series. Supt. of Govt. Print. 1908.

- ↑ Metcalf, Barbara Daly (1984). Moral Conduct and Authority: The Place of Adab in South Asian Islam. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520046603.

- ↑ Imperial gazetteer of India: provincial series. Supt. of Govt. Print. 1908.

- ↑ Ali, M. Athar (2006). Mughal India: Studies in Polity, Ideas, Society, and Culture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195648607.

- ↑ Singh, Pashaura (2002-12-27). The Bhagats of the Guru Granth Sahib: Sikh Self-Definition and the Bhagat Bani. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199087723.

- ↑ Singh, Rishi (2015-04-23). State Formation and the Establishment of Non-Muslim Hegemony: Post-Mughal 19th-century Punjab. SAGE Publications India. ISBN 9789351505044.

- ↑ Singh, Rishi (2015-04-23). State Formation and the Establishment of Non-Muslim Hegemony: Post-Mughal 19th-century Punjab. SAGE Publications India. ISBN 9789351505044.

- 1 2 3 Nadiem, Ihsan H. (2005). Punjab: land, history, people. al-Faisal Nashran. ISBN 9789695032831.

- ↑ Glover, William J. (2008). Making Lahore Modern: Constructing and Imagining a Colonial City. U of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9781452913384.

- 1 2 Talbot, Ian (2013-12-16). Khizr Tiwana, the Punjab Unionist Party and the Partition of India. Routledge. ISBN 9781136790362.

- 1 2 3 Boivin, Michel; Delage, Remy (2015-12-22). Devotional Islam in Contemporary South Asia: Shrines, Journeys and Wanderers. Routledge. ISBN 9781317380009.

- ↑ "Celebrating Urs in Amritsar". The Tribune.

- ↑ Pakpattan

- ↑ Maps (Map). Google Maps.

- 1 2 Mubeen, Muhammad (2015). Delage, Remy; Boivin, Michel, eds. Devotional Islam in Contemporary South Asia: Shrines, Journeys and Wanderers. Routledge. ISBN 1317379993.