Chinese Communist Revolution

| Chinese Communist Revolution 中國新民主主義革命 第二次國共內戰 (Second Kuomintang-Communist Civil War) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Chinese Civil War (since 1927) Part of the Cold War (1947–1991) | |||||||

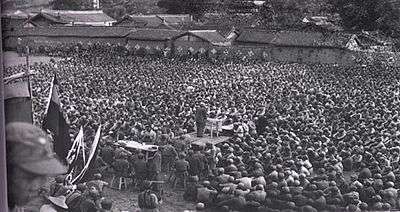

People's Liberation Army occupies the Presidential Palace in Nanjing. April, 1949 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 250,000 in three campaigns | 1.5 million in three campaigns[1] | ||||||

The Chinese Communist Revolution started from 1946, after the end of Second Sino-Japanese War, and was the second part of the Chinese Civil War. It was the culmination of the Chinese Communist Party's drive to power after its founding in 1921. In the Chinese media, this period is known as the War of Liberation (simplified Chinese: 解放战争; traditional Chinese: 解放戰爭; pinyin: Jiěfàng Zhànzhēng).

Historical background

The Communist Party of China was founded in 1921. After a period of slow growth and alliance with the Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party), the alliance broke down and the Communists fell victim in 1927 to a purge carried out by the Kuomintang under the leadership of Chiang Kai-shek.[2] After 1927, the Communists retreated to the countryside and built up local bases throughout the country and continued to hold them until the Long March. During the Japanese invasion and occupation, the Communists built more bases in the Japanese occupied zones and relied on them as headquarters.[3]

The Civil War, 1945–1949

The Nationalists had an advantage in both troops and weapons, controlled a much larger territory and population, and enjoyed broad international support. The communists were well established in the north and northwest. The best trained Nationalist troops had been lost in early battles against the better equipped Japanese army and in Burma, while the communists had suffered less severe losses. The Soviet Union, though distrustful, provided aid to the communists, and the United States assisted the Nationalists with hundreds of millions of dollars' worth of military supplies, as well as airlifting Nationalist troops from central China to Manchuria, an area Chiang Kai-shek saw as strategically vital to retake. Chiang determined to confront the PLA in Manchuria and committed his troops in one decisive battle in the autumn of 1948. The strength of Nationalist troops in July 1946 was 4.3 million, of which 2.2 million were well-trained and ready for country-wide mobile combat.[4][5][6]

Result

On October 1, 1949, Mao Zedong proclaimed the establishment of the People's Republic of China. Chiang Kai-shek, 600,000 Nationalist troops, and about two million Nationalist-sympathizer refugees retreated to the island of Taiwan. After that, resistance to the Communists on the mainland was substantial but scattered, such as in the far south. An attempt to take the Nationalist-controlled island of Kinmen was thwarted in the Battle of Kuningtou. In December 1949 Chiang proclaimed Taipei, Taiwan the temporary capital of the Republic, and continued to assert his government as the sole legitimate authority of all China, while the PRC government continued to call for the unification of all China. The last direct fighting between Nationalist and Communist forces ended with the communist capture of Hainan Island in May 1950, though shelling and guerrilla raids continued for a number of years. In June 1950, the outbreak of the Korean War led the American government to place the United States Seventh Fleet in the Taiwan Strait to prevent either side from attacking the other.[7]

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Lynch, Michael (2010). The Chinese Civil War 1945–49. Osprey Publishing. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-84176-671-3.

- ↑ Hunt, Michael H. (2015). The World Transformed 1945 to the present. Oxford University Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-19-937102-0.

- ↑ Patrick Fuliang Shan, “Local Revolution, Grassroots Mobilization and Wartime Power Shift to the Rise of Communism,” in Xiaobing Li (ed.), Evolution of Power: China’s Struggle, Survival, and Success, Lexington and Rowman & Littlefield, 2013, pp. 3-25.

- ↑ 《中华民国国民政府军政职官人物志》 (in Chinese). p. 374.

- ↑ 《国民革命与统一建设:20世纪初孙中山及国共人物的奋斗》 (in Chinese). p. 12.

- ↑ 《国民革命与黃埔军校:纪念黃埔军校建校80周年学術论文集》 (in Chinese). p. 450.

- ↑ "Army Department Teletype conference, ca. June 1950". Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. US Department of Defense. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

Sources

- Franke, W., A Century of Chinese Revolution, 1851–1949 (Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1970).

Further reading

- Blanco, Lucien. Origins of the Chinese Revolution, 1915–1949. Stanford University Press, 1971. Chapter 1, pages 1-26 (Archive). -- hosted at CÉRIUM (Centre d’études et de recherches internationales) at the Université de Montréal