C. Wright Mills

| C. Wright Mills | |

|---|---|

| Born |

Charles Wright Mills August 28, 1916 Waco, Texas |

| Died |

March 20, 1962 (aged 45) West Nyack, New York[1] |

| Alma mater | University of Texas at Austin (BA, MA); University of Wisconsin–Madison (PhD) |

| Occupation | Political sociologist |

| Known for |

Elite theory Sociological imagination Criticism of abstract empiricism Coining the term "grand theory" |

Charles Wright Mills (August 28, 1916 – March 20, 1962) was an American sociologist, and a professor of sociology at Columbia University from 1946 until his death in 1962. Mills was published widely in popular and intellectual journals, and is remembered for several books such as The Power Elite, which introduced that term and describes the relationships and class alliances among the US political, military, and economic elites; White Collar: The American Middle Classes, on the American middle class; and The Sociological Imagination, which presents a model of analysis for the interdependence of subjective experiences within a person's biography, the general social structure, and historical development.

Mills was concerned with the responsibilities of intellectuals in post-World War II society, and he advocated public and political engagement over disinterested observation. Mills's biographer, Daniel Geary, writes that Mills's writings had a "particularly significant impact on New Left social movements of the 1960s."[2] Indeed, it was Mills who popularized the term "New Left" in the U.S. in a 1960 open letter, Letter to the New Left.[3]

Early life

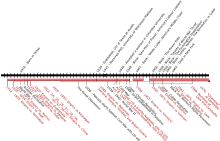

Mills was born in Waco, Texas on August 28, 1916. He lived in Texas until he was 23.[1] His father, Charles Grover Mills, worked as an insurance salesman, while his mother, Frances Wright Mills, stayed at home as a housewife.[1][4] His father moved to Texas from his home state of Florida, and his mother and maternal grandparents were all born and raised in Texas.[1]:21 His family moved constantly when he was growing up and as a result, he lived a relatively isolated life with few continuous relationships.[5] Mills spent time living in the following cities (in order): Waco, Wichita Falls, Fort Worth, Sherman, Dallas, Austin, and San Antonio.[1]:25 He graduated from Dallas Technical High School in 1934.[6]

College years

Mills initially attended Texas A&M University but left after his first year and subsequently graduated from the University of Texas at Austin in 1939 with a bachelor's degree in sociology and a master's degree in philosophy. By the time that he graduated, Mills had already been published in the two leading sociology journals in the US: the American Sociological Review and the American Journal of Sociology.[7]:40

While studying at Texas, Mills met his first wife, Dorothy Helen Smith, who was also a student there seeking a master's degree in sociology. She had previously attended Oklahoma College for Women, where she graduated with a bachelor's degree in commerce.[1]:34 They were married in October 1937. After their marriage Dorothy Helen, or "Freya," worked as a staff member of the director of the Women’s Residence Hall at the University of Texas to support the couple while Mills completed his graduate work; she typed and copy edited much of his work, including his Ph.D. dissertation.[1]:35 There, he met Hans Gerth, a professor in the Department of Sociology, who became a mentor and friend although Mills did not take any classes with Gerth. In August 1940, Freya divorced Mills, but the couple remarried in March 1941. Their daughter, Pamela, was born on January 15, 1943.[1]

Mills received his Ph.D. in sociology from the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1942. His dissertation was entitled "A Sociological Account of Pragmatism: An Essay on the Sociology of Knowledge."[1]:77 Mills refused to revise his dissertation while it was reviewed. It was later accepted without approval from the review committee.[8] Mills left Wisconsin in early 1942 once he had been appointed Professor of Sociology at the University of Maryland, College Park.

Early career

During his work as an Associate Professor of Sociology from 1941 until 1945 at the University of Maryland, College Park, Mills’s awareness and involvement in American politics grew. Mills became friends with historians, Richard Hofstadter, Frank Freidel, and Ken Stampp during World War II. The four academics collaborated on many topics and so each wrote about many contemporary issues surrounding the war and how it affected American society.[1]:47

In the mid-1940s while he was still at Maryland, Mills began contributing 'journalistic sociology' and opinion pieces to intellectual journals such as The New Republic, The New Leader, and politics, the journal established by his friend Dwight Macdonald in 1944.[7]:67–71[9]

In 1945, Mills moved to New York after securing a research associate position at Columbia University's Bureau of Applied Social Research. Mills separated from Freya with the move, and the couple divorced in 1947. Mills was appointed Assistant Professor in the University's sociology department in 1946.[10] Mills received a grant of $2,500 from the Guggenheim Foundation in April, 1945 to fund his research in 1946. During that time, he wrote White Collar which was finally published in 1951.[1]:81

In 1946, From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, a translation of Weber's essays co-authored with Hans Gerth, was published.[1]:47 In 1953, the two published a second work, Character and Social Structure: The Psychology of Social Institutions.[1]:93

In 1947, Mills married his second wife, Ruth Harper, a Bureau of Applied Social Research statistician who worked with Mills on New Men of Power (1948), White Collar (1951), and The Power Elite (1956). In 1949, Mills and Harper went to Chicago so that Mills could serve as a visiting professor at the University of Chicago; Mills returned to teaching at Columbia after a semester at the University of Chicago and was promoted to Associate Professor of Sociology on July 1, 1950. Their daughter, Kathryn, was born on July 14, 1955. Mills was promoted to Professor of Sociology at Columbia on July 1, 1956. From 1956 to 1957, the family moved to Copenhagen, where Mills acted as a Fulbright lecturer at the University of Copenhagen. Mills and Harper separated in December 1957, when Mills returned from Copenhagen alone, and he divorced in 1959.[1]

Later years

Mills married his third wife, Yaroslava Surmach, an American artist of Ukrainian descent, and settled in Rockland County, New York in 1959. Their son, Nikolas Charles, was born on June 19, 1960.[1]

In August 1960, Mills spent time in Cuba where he worked on developing his text Listen, Yankee. He spent some of his time in Cuba interviewing Fidel Castro, who claimed to having read and studied Mills's The Power Elite.[1]:312

Mills was described as a man in a hurry, and aside from his hurried nature, he was largely known for his combativeness. Both his private life, with three marriages, a child from each, and several affairs, and his professional life, which involved challenging and criticizing many of his professors and coworkers, have been characterized as "tumultuous". He wrote a fairly obvious, though slightly veiled, essay in criticism of the former chairman of the Wisconsin department, and he called the senior theorist there, Howard P. Becker, a "real fool". On one special occasion, when Mills was honored during a visit to the Soviet Union as a major critic of American society, he criticized censorship in the Soviet Union through his toast to an early Soviet leader who was "purged and murdered by the Stalinists." He said, "To the day when the complete works of Leon Trotsky are published in the Soviet Union!"[4]

In one of Mills's biographies written by Irving Louis Horowitz, the author writes about Mills's acute awareness of his heart condition and speculates that it affected the way he lived his adult life. Mills was described as someone who worked fast, yet efficiently. That is argued to be a result of his knowing that he would not live long due to his heart health. Horowitz describes Mills as “a man in search of his destiny”.[7]:81

Mills suffered from a series of heart attacks throughout his life and his fourth[4] attack led to his death on March 20, 1962.[11]

Influences

C. Wright Mills was heavily influenced by pragmatism, specifically the works of George Herbert Mead, John Dewey, Charles Sanders Peirce, and William James.[12] The social structure aspects of Mills's works is largely shaped by Max Weber and the writing of Karl Mannheim, who followed Weber's work closely. Mills also acknowledged a general influence of Marxism; he noted that Marxism had become an essential tool for sociologists and therefore all must naturally be educated on the subject; any Marxist influence was then a result of sufficient education. Neo-Freudianism also helped shape Mills's work.[13]

Mills was an intense student of philosophy before he became a sociologist and his vision of radical, egalitarian democracy was a direct result of the influence of ideas from Thorstein Veblen, John Dewey, and Mead.[14] During his time at the University of Wisconsin, Mills was heavily influenced by Hans Gerth, a Sociology Professor from Germany. Mills gained an insight into European learning and sociological theory from Gerth.[1]:39

Books

From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology (1946) was edited and translated in collaboration with Gerth.[1] Mills and Gerth had begun began collaborating in 1940, and they selected a few of Weber’s original German text and translated them into English.[15] The preface of the book begins by explaining the disputable difference of meaning that English words give to German writing. The authors attempt to explain their devotion to being as accurate as possible in translating Weber's writing.

The New Men of Power: America's Labor Leaders (1948) studies the "Labor Metaphysic" and the dynamic of labor leaders cooperating with business officials. The book concludes that the labor movement had effectively renounced its traditional oppositional role and become reconciled to life within a capitalist system. Appeased by "bread and butter" economic policies, unions had adopted a pliant and subordinate role in the new structure of American power.

The Puerto Rican Journey (1950) was written in collaboration with Clarence Senior and Rose Kohn Goldsen. It documents a methodological study and does not address theoretical sociological framework.[1][13]

White Collar: The American Middle Classes (1951) offers a rich historical account of the middle classes in the United States and contends that bureaucracies have overwhelmed middle-class workers, robbing them of all independent thought and turning them into near-automatons, oppressed but cheerful. Mills states there are three types of power within the workplace: coercion or physical force; authority; and manipulation.[16] Through this piece, the thoughts of Mills and Weber seem to coincide in their belief that Western Society is trapped within the iron cage of bureaucratic rationality, which would lead society to focus more on rationality and less on reason.[16] Mills's fear was that the middle class was becoming "politically emasculated and culturally stultified," which would allow a shift in power from the middle class to the strong social elite.[17] Middle-class workers receive an adequate salary but have become alienated from the world because of their inability to affect or change it.

Character and Social Structure (1953) was co-authored with Gerth. This was considered his most theoretically sophisticated work. Mills later came into conflict with Gerth, though Gerth positively referred to him as, "an excellent operator, a whippersnapper, promising young man on the make, and Texas cowboy à la ride and shoot."[4] Generally speaking, Character and Social Structure combines the social behaviorism and personality structure of pragmatism with the social structure of Weberian sociology. It is centered on roles, how they are interpersonal, and how they are related to institutions.[13]

The Power Elite (1956) describes the relationships among the political, military, and economic elites, noting that they share a common world view; that power rests in the centralization of authority within the elites of American society.[16] The centralization of authority is made up of the following components: a "military metaphysic," in other words a military definition of reality; "class identity," recognizing themselves as separate from and superior to the rest of society; "interchangeability" (they move within and between the three institutional structures and hold interlocking positions of power therein); cooperation/socialization, in other words, socialization of prospective new members is done based on how well they "clone" themselves socially after already established elites. Mills's view on the power elite is that they represent their own interest, which include maintaining a "permanent war economy" to control the ebbs and flow of American Capitalism and the masking of "a manipulative social and political order through the mass media."[17]In a contemporary extension of Mills' Power Elite, Dr. Asadi [18]suggests that the modern World System is highly militarized and a counterpart of the US permanent war economy where a global division of labor based on military Keynesian stabilization exists concomitant with economic accumulation, and a confluence of interests between (global) military, economic and political elites.

The Causes of World War Three (1958) and Listen, Yankee (1960) were important works that followed. In both, Mills attempts to create a moral voice for society and make the power elite responsible to the "public."[1][13] Although Listen, Yankee was considered highly controversial, it was an exploration of the Cuban Revolution written from the viewpoint of a Cuban revolutionary and was a very innovative style of writing for that period in American history.[1]

The Sociological Imagination (1959), which is considered Mills's most influential book,[19] describes a mindset for studying sociology, the sociological imagination, that stresses being able to connect individual experiences and societal relationships. Three components form the sociological imagination:

- History: why society is what it is and how it has been changing for a long time and how history is being made in it

- Biology: the nature of "human nature" in a society and what kinds of people inhabit a particular society

- Social Structure: how the various institutional orders in a society function, which ones are dominant, how they are kept together, how they might be changing too, etc.

Mills asserts that a critical task for social scientists is to "translate personal troubles into public issues".[20] The distinction between troubles and issues is that troubles relate to how a single person feels about something while issues refer to a society affects groups of people. For instance, a man who cannot find employment is experiencing a trouble, while a city with a massive unemployment rate makes it not just a personal trouble but an issue.[21] Sociologists, then, rightly connect their autobiographical, personal challenges to social institutions. Social scientists should then connect those institutions to social structures and locate them within a historical narrative.

The version of Images of Man: The Classic Tradition in Sociological Thinking (1960) worked on by C. Wright Mills is simply an edited copy with the addition of an introduction written himself.[1] Through this work, Mills explains that he believes the use of models is the characteristic of classical sociologists, and that these models are the reason classical sociologists maintain relevance.[13]

The Marxists (1962) takes Mills's explanation of sociological models from Images of Man and uses it to criticize modern liberalism and Marxism. He believes that the liberalist model does not work and cannot create an overarching view of society, but rather it is more of an ideology for the entrepreneurial middle class. Marxism, however, may be incorrect in its overall view, but it has a working model for societal structure, the mechanics of the history of society, and the roles of individuals. One of Mills's problems with the Marxist model is that it uses units that are small and autonomous, which he finds too simple to explain capitalism. Mills then provides discussion on Marx as a determinist.[13]

Legacy

Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes dedicated his novel The Death of Artemio Cruz (1962) to Mills and called him the "true voice of North America, friend and companion in the struggle of Latin America." Fuentes was a fan of Mills's Listen, Yankee and appreciated Mills's insight into what he believed Cubans were experiencing as citizens of a country undergoing revolutionary change.[1]

Mills's legacy can be most deeply felt through the printed compilation of his letters and other works called C Wright Mills: Letters and Autobiographical Writings, edited by two of his children, Kathryn and Pamela Mills. In the book's introduction, Dan Wakefield states that Mills's sociological vision of American society is one that transcends the field of sociology. Mills presented his ideas as a way to keep American society from falling into the trap of what is known as "mass society." Many scholars argue that Mills’ ideas sparked the radical movements of the 1960s, which took place after he died. His work was recognized in the United States and was also greatly appreciated abroad, having appeared in 23 languages.

Above all, Wakefield remembers Mills's character most as being surrounded by controversy:

| “ | In that era of cautious professors in gray flannel suits, Mills came roaring into Morningside Heights on his BMW motorcycle, wearing plaid shirts, old jeans, and work boots, carrying his books in a duffel bag strapped across his broad chest…. In the classroom as well as in the pages of his widely read books, Mills was a great teacher. His lectures matched the flamboyance of his personal image, as he managed to make entertaining the heavyweight social theories of Karl Mannheim, Max Weber, and José Ortega y Gasset. He shocked us [students] out of our "silent generation" student torpor by pounding his desk and proclaiming that each man should build his own house (as he did himself) and that, by God, with the proper study, we should each be able to build our own car![1]:6 | ” |

In 1964, the Society for the Study of Social Problems established the C. Wright Mills Award for the book that "best exemplifies outstanding social science research and a great understanding the individual and society in the tradition of the distinguished sociologist, C. Wright Mills."[22]

Outlook

There has long been debate over Mills's intellectual outlook. Mills is often seen as a "closet Marxist" because of his emphasis on social classes and their roles in historical progress and attempt to keep Marxist traditions alive in social theory. Just as often however, others argue that Mills more closely identified with the work of Max Weber, whom many sociologists interpret as an exemplar of sophisticated (and intellectually adequate) anti-Marxism and modern liberalism. However, Mills clearly gives precedence to social structure described by the political, economic and military institutions and not culture, which is presented in its massified form as means to ends sought by the power elite, which puts him firmly in the Marxist and not Weberian camp, so much that in his collection of classical essays, Weber's Protestant Ethic is not included. Weber's idea of bureaucracy as internalized social control was embraced by Mills as was the historicity of his method, but far from liberalism (being its critic), Mills was a radical who was culturally forced to distance himself from Marx while being "near" him.

While Mills never embraced the "Marxist" label, he told his closest associates that he felt much closer to what he saw as the best currents of a flexible humanist Marxism than to its alternatives. He considered himself as a "plain Marxist" working in the spirit of young Marx as he claims in his collected essays: "Power, Politics and People" (Oxford University Press, 1963). In a November 1956 letter to his friends Bette and Harvey Swados, Mills declared "[i]n the meantime, let's not forget that there's more [that's] still useful in even the Sweezy[23] kind of Marxism than in all the routineers of J. S. Mill[24] put together."

There is an important quotation from Letters to Tovarich (an autobiographical essay) dated Fall 1957 titled "On Who I Might Be and How I Got That Way":

| “ | You've asked me, 'What might you be?' Now I answer you: 'I am a Wobbly.' I mean this spiritually and politically. In saying this I refer less to political orientation than to political ethos, and I take Wobbly to mean one thing: the opposite of bureaucrat. […] I am a Wobbly, personally, down deep, and for good. I am outside the whale, and I got that way through social isolation and self-help. But do you know what a Wobbly is? It's a kind of spiritual condition. Don't be afraid of the word, Tovarich. A Wobbly is not only a man who takes orders from himself. He's also a man who's often in the situation where there are no regulations to fall back upon that he hasn't made up himself. He doesn't like bosses—capitalistic or communistic—they are all the same to him. He wants to be, and he wants everyone else to be, his own boss at all times under all conditions and for any purposes they may want to follow up. This kind of spiritual condition, and only this, is Wobbly freedom.[1]:252[25] | ” |

These two quotations are the ones chosen by Kathryn Mills for the better acknowledgement of his nuanced thinking.

It appears that Mills understood his position as being much closer to Marx than to Weber but influenced by both, as Stanley Aronowitz argued in A Mills Revival?.[26]

Mills argues that micro and macro levels of analysis can be linked together by the sociological imagination, which enables its possessor to understand the large historical sense in terms of its meaning for the inner life and the external career of a variety of individuals. Individuals can only understand their own experiences fully if they locate themselves within their period of history. The key factor is the combination of private problems with public issues: the combination of troubles that occur within the individual’s immediate milieu and relations with other people with matters that have to do with institutions of an historical society as a whole.

Mills shares with Marxist sociology and other "conflict theorists" the view that American society is sharply divided and systematically shaped by the relationship between the powerful and powerless. He also shares their concerns for alienation, the effects of social structure on the personality, and the manipulation of people by elites and the mass media. Mills combined such conventional Marxian concerns with careful attention to the dynamics of personal meaning and small-group motivations, topics for which Weberian scholars are more noted.

Mills had a very combative outlook regarding and towards many parts of his life, the people in it, and his works. In that way, he was a self-proclaimed outsider.

| “ | I am an outlander, not only regionally, but deep down and for good.[7] | ” |

C. Wright Mills gave considerable study to the Soviet Union. Invited there, where he was acknowledged for his criticism of American society, Mills used the opportunity to attack Soviet censorship. He did hold the controversial notion that the US and the Soviet Union were ruled by similar bureaucratic power elites and thus were convergent rather than divergent societies.

Above all, Mills understood sociology, when properly approached, as an inherently political endeavor and a servant of the democratic process. In The Sociological Imagination, Mills wrote:

| “ | It is the political task of the social scientist -- as of any liberal educator – continually to translate personal troubles into public issues, and public issues into the terms of their human meaning for a variety of individuals. It is his task to display in his work – and, as an educator, in his life as well -- this kind of sociological imagination. And it is his purpose to cultivate such habits of mind among the men and women who are publicly exposed to him. To secure these ends is to secure reason and individuality, and to make these the predominant values of a democratic society.[20] | ” |

Contemporary American scholar Cornel West argued in his text American Evasion of Philosophy that Mills follows the tradition of pragmatism. Mills shared Dewey's goal of a "creative democracy" and emphasis on the importance of political practice but criticized Dewey for his inattention to the rigidity of power structure in the US. Mills's dissertation was titled Sociology and Pragmatism: The Higher Learning in America, and West categorized him along with pragmatists in his time Sidney Hook and Reinhold Niebuhr as thinkers during pragmatism's "mid-century crisis."

See also

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Mills, C. Wright (2000). Mills, Kathryn; Mills, Pamela, eds. C. Wright Mills: Letters and Autobiographical Writings. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520211063.

- ↑ Radical Ambition: C. Wright Mills, the Left, and American Social Thought By Daniel Geary, p. 1.

- ↑ Mills, C. Wright (September–October 1960). "Letter to the New Left". New Left Review. New Left Review. I (5). Full text.

- 1 2 3 4 Ritzer, George (2011). Sociological Theory. New York, NY: McGraw Hill. pp. 215–217. ISBN 9780078111679.

- ↑ Crossman, Ashley. "C. Wright Mills". The New York Times Company. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ↑ Short biography of C. Wright Mills published in the Dictionary of Modern American Philosophers in 3 volumes by Thoemmes Press, Bristol, UK, 2004

- 1 2 3 4 Horowitz, Irving Louis (1983). C. Wright Mills: an American utopian. New York: Free Press. ISBN 9780029149706.

- ↑ Staff writer (2008), "Mills, C. Wright 1916-1963", in Darity, Jr., William A., International encyclopedia of the social sciences (volume 5) (2nd ed.), Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, pp. 181–183, ISBN 9780028659657 Available online.

- ↑ Elson, John (April 4, 1994). "No foolish consistency: biographical sketch of Dwight Macdonald". Time. Time Inc. 143 (14). Archived from the original on 21 January 2013.

- ↑ Geary, Daniel (2009). Radical ambition: C. Wright Mills, the left, and American social thought. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520258365.

In early 1946, he was appointed assistant professor at Columbia College

- ↑ edited; Sica, with introductions by Alan (2005). Social thought: from the Enlightenment to the present. Boston: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 0-205-39437-X.

- ↑ Oakes, Guy; Vidich, Arthur J. (1999). "Introduction". In Oakes, Guy; Vidich, Arthur J. Collaboration, reputation, and ethics in American academic life: Hans H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. p. 1. ISBN 9780252068072.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Scimecca, Joseph A. (1977). The sociological theory of C. Wright Mills. Port Washington, New York: Kennikat Press Corp. ISBN 9780804691550.

- ↑ Tilman, Rick (1984), "Introduction: our foremost dissenter", in Tilman, Rick, C. Wright Mills: a native radical and his American intellectual roots, University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, p. 1, ISBN 9780271003603.

- ↑ Oakes, Guy; Vidich, Arthur J. (1999). "Introduction". In Oakes, Guy; Vidich, Arthur J. Collaboration, reputation, and ethics in American academic life: Hans H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. p. 6. ISBN 9780252068072.

- 1 2 3 Mann, Doug (2008). Understanding society: a survey of modern social theory. Don Mills, Ont. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195421842.

- 1 2 Sim, Stuart; Parker, Noel, eds. (1997). The A–Z guide to modern social and political theorists. London: Prentice Hall, Harvester Wheatsheaf. ISBN 9780135248850.

- ↑ http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/dissertations/447/

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 September 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2015. The Sociological Imagination ranked second (outranked only by Max Weber's Economy and Society) in a 1997 survey asking members of the International Sociological Association to identify the books published in the 20th century most influential on sociologists

- 1 2 Mills, C. Wright (2000). The sociological imagination, fortieth anniversary edition. Oxford England New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195133738.

- ↑ Mills, C. Wright, "From the sociological imagination", in Massey, Gareth, Readings for sociology (Seventh ed.), New York: W. W. Norton & Company, pp. 13–18, ISBN 9780393912708

- ↑ "C. Wright Mills Award". Society for the Study of Social Problems. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- ↑ Paul M. Sweezy, founder of Monthly Review magazine, "an independent socialist magazine".

- ↑ a liberal intellectual.

- ↑ Wobblies are members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and the direct action they are favouring includes passive resistance, strikes, and boycotts. They want to build a new society according to general socialist principles but they are refusing to endorse any socialist party or any other kind of political party.

- ↑ Aronowitz, Stanley (2006), "A Mills Revival?", in Bronner, Stephen Eric; Thompson, Michael J., The logos reader: rational radicalism and the future of politics, Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, pp. 117–140, ISBN 9780813191485,

These perspectives owed as much to the methodological precepts of Emile Durkheim as they did to the critical theory of Karl Marx and Max Weber. Using many of the tools of conventional social inquiry: surveys, interviews, data analysis—charts included—Mills takes pains to stay close to the “data” until the concluding chapters. But what distinguishes Mills from mainstream sociology, and from Weber, with whom he shares a considerable portion of his intellectual outlook, is the standpoint of radical social change, not of fashionable sociological neutrality.

Available online.

Further reading

- Aptheker, Herbert (1960). The World of C. Wright Mills. New York: Marzani and Munsell. OCLC 244597.

- Aronowitz, Stanley (2006), "A Mills Revival?", in Bronner, Stephen Eric; Thompson, Michael J., The logos reader: rational radicalism and the future of politics, Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, pp. 117–140, ISBN 9780813191485. Available online.

- Aronowitz, Stanley (2012). Taking it Big: C. Wright Mills and the Making of Political Intellectuals. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231135405.

- Domhoff, G. William (November 2006). "Review: Mills's The Power Elite 50 Years Later". Contemporary Sociology. Sage for the American Sociological Association. 35 (6): 547–550. doi:10.1177/009430610603500602. JSTOR /30045989. Full text.

- Dowd, Douglas F. (Winter 1964). "On Veblen, Mills... and the decline of criticism". Dissent. University of Pennsylvania Press. 11 (1): 29–38.

- Eldridge, John E.T. (1983). C. Wright Mills. Key Sociologists Series. Chichester West Sussex London New York: E. Horwood Tavistock Publications. ISBN 9780853125341.

- Geary, Daniel (2009). Radical ambition: C. Wright Mills, the left, and American social thought. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520258365.

In early 1946, he was appointed assistant professor at Columbia College

- Geary, Daniel (2008). "'Becoming International Again': C. Wright Mills and the Emergence of a Global New Left". Journal of American History. 95 (3): 710–736. doi:10.2307/27694377.

- Horowitz, Irving Louis (1983). C. Wright Mills: an American utopian. New York: Free Press. ISBN 9780029149706.

- Hayden, Tom (2006). Radical nomad: C. Wright Mills and his times. Boulder, Colorado: Paradigm Publishers. ISBN 9781594512025. With contemporary reflections by Stanley Aronowitz, Richard Flacks, and Charles Lemert

- Kerr, Keith (2009). Postmodern cowboy: C. Wright Mills and a new 21st century sociology. East Boulder, Colorado: Paradigm Publishers. ISBN 9781594515798.

- Landau, Saul (Spring 1963). "C. Wright Mills — The Last Six Months". Root and Branch. Root and Branch Press. 2: 2–15.

- Mattson, Kevin (2002). Intellectuals in action: the origins of the new left and radical liberalism, 1945-1970. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 9780271022062.

- Milliband, Ralph. "C. Wright Mills," New Left Review, whole no. 15 (May–June 1962), pp. 15–20.

- Muste, A.J.; Howe, Irving (Spring 1959). "C. Wright Mills' Program: Two Views". Dissent. University of Pennsylvania Press. 6 (2): 189–196.

- Swados, Harvey (Winter 1963). "C. Wright Mills: A Personal Memoir". Dissent. University of Pennsylvania Press. 10 (1): 35–42.

- Thompson, E.P. (July–August 1979). "C. Wright Mills: The Responsible Craftsman". Radical America. Students for a Democratic Society. 13 (4): 60–73. Pdf of magazine.

- Tilman, Rick (1984). C. Wright Mills: a native radical and his American intellectual roots. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 9780271003603.

- Treviño, A. Javier (2012). The social thought of C. Wright Mills. Thousand Oaks, California: Pine Forge Press. ISBN 9781412993937.

- Frauley, Jon, ed. (2015). C. Wright Mills and the criminological imagination: prospects for creative inquiry. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9781472414755.

Primary sources

- Mills, C. Wright (2000). Mills, Kathryn; Mills, Pamela, eds. C. Wright Mills: Letters and Autobiographical Writings. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520211063.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: C. Wright Mills |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Wright Mills. |

- Official website

- C.Wright Mills-The Power Elite

- Frank Elwell's page at Rogers State

- An interview with Mills's daughters, Kathryn and Pamela

- C. Wright Mills and Radical Sociology-Joseph A. Scimecca

- Mills-On Intellectual Craftsmanship

- Contemporary C. Wright Mills

- C.W. Mills, Structure of Power in American Society, British Journal of Sociology, Vol.9, No.1 1958

- A Mills Revival?

- C. Wright Mills, The Causes of World War Three

- "Letter to the New Left". New Left Review. New Left Review. I (5). September–October 1960. Full text.

- Sociology-Congress in Köln 2000 workshop: C. Wright Mills and his Power Elite: Actuality today?

- John D Brewer, C. Wright Mills, the LSE and the sociological imagination

- Daniel Geary (2009). Radical Ambition. C. Wright Mills, the Left, and American Social Thought. University of California Press. Chapter 6

- Daniel Geary in C.S.Soong's radio program Against the Grain (KPFA 94,1 MHz) on C. Wright Mills