Hegemony

| Part of the Politics series | ||||||||

| Basic forms of government | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power structure | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Power source | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Power ideology | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Politics portal | ||||||||

Hegemony (UK: /hɪˈɡɛməni, ![]()

In the 19th century, hegemony came to denote the "Social or cultural predominance or ascendancy; predominance by one group within a society or milieu". Later, it could be used to mean "a group or regime which exerts undue influence within a society".[7] Also, it could be used for the geopolitical and the cultural predominance of one country over others, from which was derived hegemonism, as in the idea that the Great Powers meant to establish European hegemony over Asia and Africa.[8]

In international relations theory, hegemony denotes a situation of (i) great material asymmetry in favour of one state, who has (ii) enough military power to systematically defeat any potential contester in the system, (iii) controls the access to raw materials, natural resources, capital and markets, (iv) has competitive advantages in the production of value added goods, (v) generates an accepted ideology reflecting this status quo; and (vi) is functionally differentiated from other states in the system, being expected to provide certain public goods such as security, or commercial and financial stability.

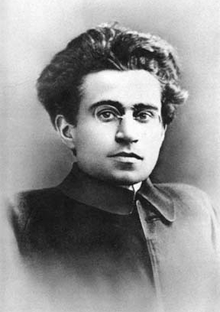

The Marxist theory of cultural hegemony, associated particularly with Antonio Gramsci, is the idea that the ruling class can manipulate the value system and mores of a society, so that their view becomes the world view (Weltanschauung): in Terry Eagleton's words, "Gramsci normally uses the word hegemony to mean the ways in which a governing power wins consent to its rule from those it subjugates".[9] In contrast to authoritarian rule, cultural hegemony "is hegemonic only if those affected by it also consent to and struggle over its common sense".[10]

In cultural imperialism, the leader state dictates the internal politics and the societal character of the subordinate states that constitute the hegemonic sphere of influence, either by an internal, sponsored government or by an external, installed government.

Etymology

From the post-classical Latin word hegemonia (from 1513 or earlier) from the Greek word ἡγεμονία hēgemonía, meaning "authority, rule, political supremacy", related to the word ἡγεμών hēgemōn "leader".[11]

Historical examples

8th–1st centuries BC

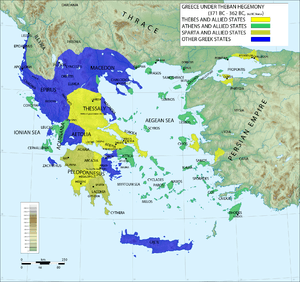

In the Greco–Roman world of 5th century BC European classical antiquity, the city-state of Sparta was the hegemon of the Peloponnesian League (6th to 4th centuries BC) and King Philip II of Macedon was the hegemon of the League of Corinth in 337 BC (a kingship he willed to his son, Alexander the Great). Likewise, the role of Athens within the short-lived Delian League (478–404 BC) was that of a "hegemon".[12] Ancient historians such as Xenophon and Ephorus were the first who used the term in its modern sense.[13]

In Ancient East Asia, Chinese hegemony existed during the Spring and Autumn period (c. 770–480 BC), when the weakened rule of the Eastern Zhou Dynasty led to the relative autonomy of the Five Hegemons (Ba in Chinese [霸]). They were appointed by feudal lord conferences, and thus were nominally obliged to uphold the imperium of the Zhou Dynasty over the subordinate states.[14]

1st–14th centuries AD

1st and 2nd century Europe was dominated by the hegemonic peace of the Pax Romana. It was instituted by the emperor Augustus, and was accompanied by a series of brutal military campaigns.[15]

From the 7th century to the 12th century, the Umayyad Caliphate and later Abbasid Caliphate dominated the vast territories they governed, with other states like the Byzantine Empire paying tribute.[16]

In 7th century India, Harsha, ruler of a large empire in northern India from AD 606 to 647, brought most of the north under his hegemony. He preferred not to rule as a central government, but left "conquered kings on their thrones and contenting himself with tribute and homage."[17]

From the late 9th to the early 11th century, the empire developed by Charlemagne achieved hegemony in Europe, with dominance over France, Italy and Burgundy.[18]

During the 14th century, the Crown of Aragon became the hegemon in the Mediterranean Sea.[19]

15th–19th centuries

In The Politics of International Political Economy, Jayantha Jayman writes "If we consider the Western dominated global system from as early as the 15th century, there have been several hegemonic powers and contenders that have attempted to create the world order in their own images." He lists several contenders for historical hegemony.[20]

- Portugal 1494 to 1580 (end of Italian Wars to Spanish/Hapsburg assimilation of Portugal). Based on Portugal's dominance in navigation.

- Spain 1516 to 1659 (Ascension of Charles I of Spain to Treaty of the Pyrenees). Based on the Spanish dominance of the European battlefields and the global exploration and colonization of the New World.

- The Netherlands 1580 to 1688 (1579 Treaty of Utrecht marks the foundation of the Dutch Republic to the Glorious Revolution, William of Orange's arrival in England). Based on Dutch control of credit and money.

- Britain 1688 to 1792 (Glorious Revolution to Napoleonic Wars). Based on British textiles and command of the high seas.

- Britain 1815 to 1914 (Congress of Vienna to World War I). Based on British industrial supremacy and railroads.

Phillip IV tried to restore the Habsburg dominance but, by the middle of the 17th century "Spain's pretensions to hegemony (in Europe) had definitely and irremediably failed."[21][22]

In late 16th and 17th-century Holland, the Dutch Republic's mercantilist dominion was an early instance of commercial hegemony, made feasible with the development of wind power for the efficient production and delivery of goods and services. This, in turn, made possible the Amsterdam stock market and concomitant dominance of world trade.[23]

In France, King Louis XIV (1638–1715) and (Emperor) Napoleon I (1799–1815) attempted French hegemony via economic, cultural and military domination of most of Continental Europe. However, Jeremy Black writes that, because of Britain, France "was unable to enjoy the benefits" of this hegemony.[24]

After the defeat and exile of Napoleon, hegemony largely passed to the British Empire, which became the largest empire in history, with Queen Victoria (1837–1901) ruling over one-quarter of the world's land and population at its zenith. Like the Dutch, the British Empire was primarily seaborne; many British possessions were located around the rim of the Indian Ocean, as well as numerous islands in the Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea. Britain also controlled the Indian subcontinent and large portions of Africa.[25]

In Europe, Germany, rather than Britain, may have been the strongest power after 1871, but Samuel Newland writes:

Bismarck defined the road ahead as … no expansion, no push for hegemony in Europe. Germany was to be the strongest power in Europe but without being a hegemon. … His basic axioms were first, no conflict among major powers in Central Europe; and second, German security without German hegemony."[26]

20th century

The early 20th century, like the late 19th century was characterized by multiple Great Powers but no global hegemon. World War I weakened the strongest of the Imperial Powers, Great Britain, but also strengthened the United States and, to a lesser extent, Japan. Both of these states' governments pursued policies to expand their regional spheres of influence, the US in Latin America and Japan in East Asia. France, the UK, Italy, the Soviet Union and later Nazi Germany (1933–1945) all either maintained imperialist policies based on spheres of influence or attempted to conquer territory but none achieved the status of a global hegemonic power.[27]

After the Second World War, the United Nations was established and the five strongest global powers (China, France, the UK, the US, and the USSR) were given permanent seats on the U.N. Security Council, the organization's most powerful decision making body. Following the war, the US and the USSR were the two strongest global powers and this created a bi-polar power dynamic in international affairs, commonly referred to as the Cold War. The hegemonic conflict was ideological, between communism and capitalism, as well as geopolitical, between the Warsaw Pact countries (1955–1991) and NATO/SEATO/CENTO countries (1949–present). During the Cold War both hegemons competed against each other directly (during the arms race) and indirectly (via proxy wars). The result was that many countries, no matter how remote, were drawn into the conflict when it was suspected that their governments' policies might destabilize the balance of power. Reinhard Hildebrandt calls this a period of "dual-hegemony", where "two dominant states have been stabilizing their European spheres of influence against and alongside each other."[28] Proxy wars became battle grounds between forces supported either directly or indirectly by the hegemonic powers and included the Korean War, the Laotian Civil War, the Arab–Israeli conflict, the Vietnam War, the Afghan War, the Angolan Civil War, and the Central American Civil Wars.[29]

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 the United States was the world's sole hegemonic power.[30]

21st century

Various perspectives on whether the US was or continues to be a hegemon have been presented since the end of the Cold War. The American political scientists John Mearsheimer and Joseph Nye have argued that the US is not a true hegemon because it has neither the financial nor the military resources to impose a proper, formal, global hegemony.[31] On the other hand, Anna Cornelia Beyer, in her book about counter-terrorism, argues that global governance is a product of American leadership and describes it as hegemonic governance.[32]

The French Socialist politician Hubert Védrine in 1999 described the US as a hegemonic hyperpower, because of its unilateral military actions worldwide.[33]

Pentagon strategist Edward Luttwak, in The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire,[34] outlined three stages, with hegemonic being the first, followed by imperial. In his view the transformation proved to be fatal and eventually led to the fall of the Roman Empire. His book gives implicit advice to Washington to continue the present hegemonic strategy and refrain from establishing an empire.

In 2006, author Zhu Zhiqun claimed that China is already on the way to becoming the world hegemon and that the focus should be on how a peaceful transfer of power can be achieved between the US and China.[35] Though others have disagreed.[36]

Political science

.svg.png)

In the historical writing of the 19th century, the denotation of hegemony extended to describe the predominance of one country upon other countries; and, by extension, hegemonism denoted the Great Power politics (c. 1880s – 1914) for establishing hegemony (indirect imperial rule), that then leads to a definition of imperialism (direct foreign rule). In the early 20th century, in the field of international relations, the Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci developed the theory of cultural domination (an analysis of economic class) to include social class; hence, the philosophic and sociologic theory of cultural hegemony analysed the social norms that established the social structures (social and economic classes) with which the ruling class establish and exert cultural dominance to impose their Weltanschauung (world view)—justifying the social, political, and economic status quo—as natural, inevitable, and beneficial to every social class, rather than as artificial social constructs beneficial solely to the ruling class.[5][8][39]

From the Gramsci analysis derived the political science denotation of hegemony as leadership; thus, the historical example of Prussia as the militarily and culturally predominant province of the German Empire (Second Reich 1871–1918); and the personal and intellectual predominance of Napoleon Bonaparte upon the French Consulate (1799–1804).[40] Contemporarily, in Hegemony and Socialist Strategy (1985), Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe defined hegemony as a political relationship of power wherein a sub-ordinate society (collectivity) perform social tasks that are culturally unnatural and not beneficial to them, but that are in exclusive benefit to the imperial interests of the hegemon, the superior, ordinate power; hegemony is a military, political, and economic relationship that occurs as an articulation within political discourse.[41] Beyer analysed the contemporary hegemony of the United States at the example of the Global War on Terrorism and presented the mechanisms and processes of American exercise of power in 'hegemonic governance'.[32]

Sociology

Academics have argued that in the praxis of hegemony, imperial dominance is established by means of cultural imperialism, whereby the leader state (hegemon) dictates the internal politics and the societal character of the subordinate states that constitute the hegemonic sphere of influence, either by an internal, sponsored government or by an external, installed government. The imposition of the hegemon's way of life—an imperial lingua franca and bureaucracies (social, economic, educational, governing)—transforms the concrete imperialism of direct military domination into the abstract power of the status quo, indirect imperial domination.[42] Critics have said that this view is "deeply condescending" and "treats people ... as blank slates on which global capitalism's moving finger writes its message, leaving behind another cultural automaton as it moves on."[43]

Suggested examples of cultural imperialism include the latter-stage Spanish and British Empires, the 19th- and 20th-century Reichs of unified Germany (1871–1945),[44] and by the end of the 20th century, the United States.[45]

Culturally, hegemony also is established by means of language, specifically the imposed lingua franca of the hegemon (leader state), which then is the official source of information for the people of the society of the sub-ordinate state. Writing on language and power, Andrea Mayr says, "As a practice of power, hegemony operates largely through language."[46] In contemporary society, an example of the use of language in this way is in the way Western countries set up educational systems in African countries mediated by Western languages.[47]

Another example of this is found in the way language helped "diminish the traditions" of African Americans in the US.[48]

See also

References

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary

- ↑ "Hegemony". Oxford Advanced American Dictionary. Dictionary.com, LLC. 2014.

- ↑ "Hegemony". Merriam-Webster Online. Merriam-Webster, Inc. 2014. Retrieved 2016-02-24.

- ↑ "Hegemony". American Heritage Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2014. Retrieved 2016-02-24.

- 1 2 Chernow, Barbara A.; Vallasi, George A., eds. (1994). The Columbia Encyclopedia (Fifth ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. p. 1215. ISBN 0-231-08098-0.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary: "A leading or paramount power; a dominant state or person"

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary: Def's 2a and 2b.

- 1 2 Bullock, Alan; Trombley, Stephen, eds. (1999). The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought (Third ed.). London: HarperCollins. pp. 387–388. ISBN 0-00-255871-8.

- ↑ Terry Eagleton, Ideology: An Introduction (London: Verso, 1991).

- ↑ Laurie, Timothy (2015). "Masculinity Studies and the Jargon of Strategy: Hegemony, Tautology, Sense". Angelaki: Journal of the Theoretical Humanities. Retrieved 2016-02-24.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, "Greeks, Romans, and barbarians (from Europe, history of)": "Fusions of power occurred in the shape of leagues of cities, such as the Peloponnesian League, the Delian League, and the Boeotian League. The efficacy of these leagues depended chiefly upon the hegemony of a leading city (Sparta, Athens, or Thebes)"

- ↑ Wickersham, JM., Hegemony and Greek Historians, Rowman & Littlefield, 1994, p. x.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, "Ch'i": "As a result, Ch'i began to dominate most of China proper; in 651 BC it formed the little states of the area into a league, which was successful in staving off invasions from the semibarbarian regimes to the north and south. Although Ch'i thus gained hegemony over China, its rule was short-lived; after Duke Huan's death, internal disorders caused it to lose the leadership of the new confederation"

- ↑ Parchami, A., Hegemonic Peace and Empire: The Pax Romana, Britannica and Americana, Routledge, 2009, p. 32.

- ↑ al-Tabari, The History of al-Tabari

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, "Harsha"

- ↑ Story, J. Charlemagne: Empire and Society, Manchester University Press, 2005, p. 193.

- ↑ The Crown of Aragon: A Singular Mediterranean Empire. ISBN 978-90-04-34960-5

- ↑ Jayman. J., in Vassilis K. Fouskas, VK., The Politics of International Political Economy, Routledge, 2014, pp. 119–20.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica:"Phillip IV"

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica: "Spain under the Habsburgs.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, "Financial and economic affairs. (from Colbert, Jean-Baptiste)".

- ↑ Black, J., Great Powers and the Quest for Hegemony: The World Order Since 1500, Routledge, 2007, p. 76.

- ↑ Porter, A., The Oxford History of the British Empire: Volume III: The Nineteenth Century, Oxford University Press, 1999, p. 258.

- ↑ Newland, Samuel J (2005). Victories Are Not Enough: Limitations of the German Way of War. DIANE Publishing. p. 30. Retrieved 2016-02-24.

- ↑ Hitchens, Christopher (2002). Why Orwell Matters. New York: Basic Books. pp. 86–87. ISBN 0-465-03049-1.

- ↑ Hilderbrandt, R., US Hegemony: Global Ambitions and Decline : Emergence of the Interregional Asian Triangle and the Relegation of the US as a Hegemonic Power, the Reorientation of Europe, Peter Lang, 2009, p. 14. (Author's italics).

- ↑ Mumford, A., Proxy Warfare, John Wiley & Sons, 2013, pp. 46–51.

- ↑ Hildebrandt, R., US Hegemony: Global Ambitions and Decline : Emergence of the Interregional Asian Triangle and the Relegation of the US as a Hegemonic Power, the Reorientation of Europe, Peter Lang, 2009, pp. 9–11.

- ↑ Nye, Joseph S., Sr. (1993). Understanding International Conflicts: An Introduction to Theory and History. New York: HarperCollins. pp. 276–77. ISBN 0-06-500720-4.

- 1 2 Beyer, Anna Cornelia (2010). Counterterrorism and International Power Relations. London: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-892-1.

- ↑ Reid, JIM., Religion and Global Culture: New Terrain in the Study of Religion and the Work of Charles H. Long, Lexington Books, 2004, p. 82.

- ↑ The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire: From the First Century AD to the Third, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976).

- ↑ Zhiqun, Zhu (2006). US-China relations in the 21st century : power transition and peace. London ; New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-70208-9.

- ↑ "Forbes Yanz Hong Huang". www.forbes.com.

- ↑ "The SIPRI Military Expenditure Database". Milexdata.sipri.org. Archived from the original on March 28, 2010. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ "The 15 countries with the highest military expenditure in 2009". Archived from the original on 2010-03-28. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ Holsti, K. J. (1985). The Dividing Discipline: Hegemony and Diversity in International Theory. Boston: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0-04-327077-8.

- ↑ Cook, Chris (1983). Dictionary of Historical Terms. London: MacMillan. p. 142. ISBN 0-333-44972-X.

- ↑ Laclau, Ernest; Mouffe, Chantal (2001). Hegemony and Socialist Strategy (Second ed.). London: Verso. pp. 40–59, 125–44. ISBN 1-85984-330-1.

- ↑ Bush, B., Imperialism and Postcolonialism, Routledge, 2014, p. 123.

- ↑ Brutt-Griffler, J., in Karlfried Knapp, Barbara Seidlhofer, H. G. Widdowson, Handbook of Foreign Language Communication and Learning, Walter de Gruyter, 2009, p. 264.

- ↑ Kissinger, Henry (1994). Diplomacy. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 137–38. ISBN 0-671-65991-X.

European coalitions were likely to arise to contain Germany's Nazis growing, potentially dominant, power

As well as p. 145: "Unified Germany was achieving the strength to dominate Europe all by itself—an occurrence which Great Britain had always resisted in the past when it came about by conquest". - ↑ Schoultz, Lars (1999). Beneath the United States: A history of U.S. policy towards Latin America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Mayr, A., Language and Power: An Introduction to Institutional Discourse, A&C Black, 2008, p. 14.

- ↑ Clayton, T., Rethinking Hegemony, James Nicholas Publishers, 2006, pp. 202–03.

- ↑ Semmes, CE., Cultural Hegemony and African American Development, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1995, p. 9.

Further reading

- Beyer, Anna Cornelia (2010). Counterterrorism and International Power Relations: The EU, ASEAN and Hegemonic Global Governance. London: IB Tauris.

- DuBois, T. D. (2005). "Hegemony, Imperialism and the Construction of Religion in East and Southeast Asia". History & Theory. 44 (4): 113–31. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2303.2005.00345.x.

- Hopper, P. (2007). Understanding Cultural Globalization (1st ed.). Malden, MA: Polity Press. ISBN 978-0-7456-3557-6.

- Howson, Richard, ed. (2008). Hegemony: Studies in Consensus and Coercion. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-95544-7. Retrieved 2016-02-24.

- Joseph, Jonathan (2002). Hegemony: A Realist Analysis. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-26836-2.

- Slack, Jennifer Daryl (1996). "The Theory and Method of Articulation in Cultural Studies". In Morley, David; Chen, Kuan-Hsing. Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies. Routledge. pp. 112–27.

External links

| Look up hegemony in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Hegemonism Hegemony at Curlie (based on DMOZ)

- Mike Dorsher, Ph.D., Hegemony Online: The Quiet Convergence of Power, Culture and Computers

- Hegemony and the Hidden Persuaders – the Power of Un-common sense

- Parag Khanna, Waving Goodbye to Hegemony