Militarism

Militarism is the belief or the desire of a government or a people that a state should maintain a strong military capability and to use it aggressively to expand national interests and/or values.[1] It may also imply the glorification of the military and of the ideals of a professional military class and the "predominance of the armed forces in the administration or policy of the state"[2] (see also: stratocracy and military junta).

Militarism has been a significant element of the imperialist or expansionist ideologies of several nations throughout history. Prominent examples include the Ancient Assyrian Empire, the Greek city state of Sparta, the Roman Empire, the Aztec nation, the Kingdom of Prussia, the Habsburg/Habsburg-Lorraine Monarchies, the Ottoman Empire, the Empire of Japan, the Soviet Union, Nazi Germany, the Italian Empire during the rule of Benito Mussolini, the German Empire, the British Empire, and the First French Empire under Napoleon.

By nation

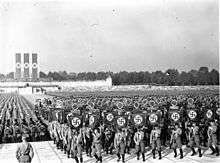

Germany

The roots of German militarism can be found in 19th-century Prussia and the subsequent unification of Germany under Prussian leadership. After Napoleon Bonaparte conquered Prussia in 1806, one of the conditions of peace was that Prussia should reduce its army to no more than 42,000 men. In order that the country should not again be so easily conquered, the King of Prussia enrolled the permitted number of men for one year, then dismissed that group, and enrolled another of the same size, and so on. Thus, in the course of ten years, he was able to gather an army of 420,000 men who had at least one year of military training. The officers of the army were drawn almost entirely from among the land-owning nobility. The result was that there was gradually built up a large class of professional officers on the one hand, and a much larger class, the rank and file of the army, on the other. These enlisted men had become conditioned to obey implicitly all the commands of the officers, creating a class-based culture of deference.

This system led to several consequences. Since the officer class also furnished most of the officials for the civil administration of the country, the interests of the army came to be considered as identical to the interests of the country as a whole. A second result was that the governing class desired to continue a system which gave them so much power over the common people, contributing to the continuing influence of the Junker noble classes.

Militarism in Germany continued after World War I and the fall of the German monarchy. During the period of the Weimar Republic (1919–1933), the Kapp Putsch, an attempted coup d'état against the republican government, was launched by disaffected members of the armed forces. After this event, some of the more radical militarists and nationalists were submerged in grief and despair into the NSDAP, while more moderate elements of militarism declined. The Third Reich was a strongly militarist state; after its fall in 1945, militarism in German culture was dramatically reduced as a backlash against the Nazi period.

The Federal Republic of Germany today maintains a large, modern military and has one of the highest defence budgets in the world, although the defence budget accounts for less than 1.5 percent of Germany's GDP, is lower than e.g. that of France or Great Britain, and does not meet the 2 percent requirement of NATO members. According to a 2017 report by the German Bundestag, the German military lacks winter clothing and tents for its troops.

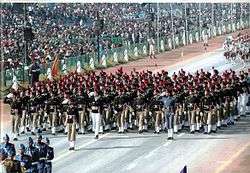

India

The rise of militarism in India dates back to the British Raj with the establishment of several Indian independence movement organizations such as the Indian National Army led by Subhas Chandra Bose. The Indian National Army (INA) played a crucial role in pressuring the British Raj after it occupied the Andaman and Nicobar Islands with the help of Imperial Japan, but the movement lost momentum due to lack of support by the Indian National Congress, the Battle of Imphal, and Bose's sudden death.

After India gained independence in 1947, tensions with neighboring Pakistan over the Kashmir dispute and other issues led the Indian government to emphasize military preparedness (see also the political integration of India). After the Sino-Indian War in 1962, India dramatically expanded its military prowess which helped India emerge victorious during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971.[3] India became the second Asian country in the world to possess nuclear weapons, culminating in the tests of 1998.[4] The Kashmiri insurgency and recent events including the Kargil War against Pakistan, assured that the Indian government remained committed to military expansion.

In recent years the government has increased the military expenditure across all branches and embarked on a rapid modernization programme.

Israel

Israel's many Arab–Israeli conflicts since the Declaration of the Establishment of the State have led to a prominence of security and defense in politics and civil society, resulting in many of Israel's former high-ranking military leaders becoming top politicians. (partial list: Yitzhak Rabin, Ariel Sharon, Ezer Weizman, Ehud Barak, Shaul Mofaz, Moshe Dayan, Yitzhak Mordechai, and Amram Mitzna).

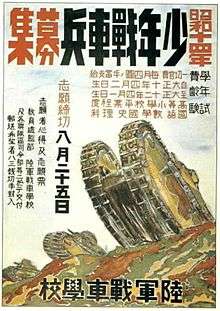

Japan

In parallel with 20th-century German militarism, Japanese militarism began with a series of events by which the military gained prominence in dictating Japan's affairs. This was evident in 15th-century Japan's Sengoku period or Age of Warring States, where powerful samurai warlords (daimyōs) played a significant role in Japanese politics. Japan's militarism is deeply rooted in the ancient samurai tradition, centuries before Japan's modernization. Even though a militarist philosophy was intrinsic to the shogunates, a nationalist style of militarism developed after the Meiji Restoration, which restored the Emperor to power and began the Empire of Japan. It is exemplified by the 1882 Imperial Rescript to Soldiers and Sailors, which called for all members of the armed forces to have an absolute personal loyalty to the Emperor.

In the 20th century (approximately in the 1920s), two factors contributed both to the power of the military and chaos within its ranks. One was the Cabinet Law, which required the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) and Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) to nominate servinet could be formed. This essentially gave the military veto power over the formation of any Cabinet in the ostensibly parliamentary country. Another factor was gekokujō, or institutionalized disobedience by junior officers.[5] It was not uncommon for radical junior officers to press their goals, to the extent of assassinating their seniors. In 1936, this phenomenon resulted in the February 26 Incident, in which junior officers attempted a coup d'état and killed leading members of the Japanese government. The rebellion enraged Emperor Hirohito and he ordered its suppression, which was successfully carried out by loyal members of the military.

In the 1930s, the Great Depression wrecked Japan's economy and gave radical elements within the Japanese military the chance to realize their ambitions of conquering all of Asia. In 1931, the Kwantung Army (a Japanese military force stationed in Manchuria) staged the Mukden Incident, which sparked the Invasion of Manchuria and its transformation into the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo. Six years later, the Marco Polo Bridge Incident outside Peking sparked the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945). Japanese troops streamed into China, conquering Peking, Shanghai, and the national capital of Nanking; the last conquest was followed by the Nanking Massacre. In 1940, Japan entered into an alliance with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, two similarly militaristic states in Europe, and advanced out of China and into Southeast Asia. This brought about the intervention of the United States, which embargoed all petroleum to Japan. The embargo eventually precipitated the Attack on Pearl Harbor and the entry of the U.S. into World War II.

In 1945, Japan surrendered to the United States, beginning the Occupation of Japan and the purging of all militarist influences from Japanese society and politics. In 1947, the new Constitution of Japan supplanted the Meiji Constitution as the fundamental law of the country, replacing the rule of the Emperor with parliamentary government. With this event, the Empire of Japan officially came to an end and the modern State of Japan was founded.

North Korea

.jpg)

Sŏn'gun (often transliterated "songun"), North Korea's "Military First" policy, regards military power as the highest priority of the country. This has escalated so much in the DPRK that one in five people serves in the armed forces, and the military has become one of the largest in the world.

Songun elevates the Korean People's Armed Forces within North Korea as an organization and as a state function, granting it the primary position in the North Korean government and society. The principle guides domestic policy and international interactions.[6] It provides the framework of the government, designating the military as the "supreme repository of power". It also facilitates the militarization of non-military sectors by emphasizing the unity of the military and the people by spreading military culture among the masses.[7] The North Korean government grants the Korean People's Army as the highest priority in the economy and in resource-allocation, and positions it as the model for society to emulate.[8] Songun is also the ideological concept behind a shift in policies (since the death of Kim Il-sung in 1994) which emphasize the people's military over all other aspects of state and the interests of the military comes first before the masses (workers).

Philippines

In the Pre-Colonial era, the Filipino people had their own forces, divided between the islands which each had its own ruler. They were called Sandig (Guards), Kawal (Knights), and Tanod. They also served as the police and watchers on the land, coastlines and seas. In 1521, The Visayan King of Mactan Lapu-Lapu of Cebu, organized the first recorded military action against the Spanish colonizers, in the Battle of Mactan.

In the 19th century during the Philippine Revolution, Andrés Bonifacio founded the Katipunan, a revolutionary organization against Spain at the Cry of Pugad Lawin. Some notable battles were the Siege of Baler, The Battle of Imus, Battle of Kawit, Battle of Nueva Ecija, the victorious Battle of Alapan and the famous Twin Battles of Binakayan and Dalahican. During Independence, the President General Emilio Aguinaldo established the Magdalo, a faction separate from Katipunan, and he declared the Revolutionary Government in the constitution of the First Philippine Republic.

And during the Filipino-American War, the General Antonio Luna as a High-Ranking General, He Ordered a Conscription to all Citizens, a mandatory form of National Services (at any War's) for the increase the density and the manpower of the Philippine Army.

During World War II, the Philippines was one of the participants, as a member of Allied Forces, the Philippines with the U.S. Forces fought the Imperial Japanese Army, (1942–1945) the notable battles is the victorious Battle of Manila, which also called "The Liberation".

During the 1970s the President Ferdinand Marcos declared P.D.1081 or martial law, which also made the Philippines a garrison state. By the Philippine Constabulary (PC) and Integrated National Police (INP), The High-School or Secondary and College Education have a compulsory Curriculum concerning the Military, and nationalism which is the "Citizens Military Training" (CMT) And "Reserve Officers Training Corps" (ROTC). But in 1986, when the constitution changed, this form of National Service Training Program became non-compulsory but still part of the Basic Education.[9]

Turkey

Militarism has a long history in Turkey.

The Ottoman Empire lasted for centuries and always relied on its military might, but militarism was not a part of everyday life. Militarism was only introduced into daily life with the advent of modern institutions, particularly schools, which became part of the state apparatus when the Ottoman Empire was succeeded by a new nation state – the Republic of Turkey – in 1923. The founders of the republic were determined to break with the past and modernise the country. There was, however, an inherent contradiction in that their modernist vision was limited by their military roots. The leading reformers were all military men and, in keeping with the military tradition, all believed in the authority and the sacredness of the state. The public also believed in the military. It was the military, after all, who led the nation through the War of Liberation (1919–1923) and saved the motherland. The 2016 attempted coup highlights the military influences within the country.

United States

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries political and military leaders reformed the US federal government to establish a stronger central government than had ever previously existed for the purpose of enabling the nation to pursue an imperial policy in the Pacific and in the Caribbean and economic militarism to support the development of the new industrial economy. This reform was the result of a conflict between Neo-Hamiltonian Republicans and Jeffersonian-Jacksonian Democrats over the proper administration of the state and direction of its foreign policy. The conflict pitted proponents of professionalism, based on business management principles, against those favoring more local control in the hands of laymen and political appointees. The outcome of this struggle, including a more professional federal civil service and a strengthened presidency and executive branch, made a more expansionist foreign policy possible.[10]

After the end of the American Civil War the national army fell into disrepair. Reforms based on various European states including Britain, Germany, and Switzerland were made so that it would become responsive to control from the central government, prepared for future conflicts, and develop refined command and support structures; these reforms led to the development of professional military thinkers and cadre.

During this time the ideas of Social Darwinism helped propel American overseas expansion in the Pacific and Caribbean.[11][12] This required modifications for a more efficient central government due to the added administration requirements (see above).

The enlargement of the U.S. Army for the Spanish–American War was considered essential to the occupation and control of the new territories acquired from Spain in its defeat (Guam, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Cuba). The previous limit by legislation of 24,000 men was expanded to 60,000 regulars in the new army bill on 2 February 1901, with allowance at that time for expansion to 80,000 regulars by presidential discretion at times of national emergency.

U.S. forces were again enlarged immensely for World War I. Officers such as George S. Patton were permanent captains at the start of the war and received temporary promotions to colonel.

Between the first and second world wars, the US Marine Corps engaged in questionable activities in the Banana Wars in Latin America. Retired Major General Smedley Butler, who was at the time of his death the most decorated Marine, spoke strongly against what he considered to be trends toward fascism and militarism. Butler briefed Congress on what he described as a Business Plot for a military coup, for which he had been suggested as leader; the matter was partially corroborated, but the real threat has been disputed. The Latin American expeditions ended with Franklin D. Roosevelt's Good Neighbor policy of 1934.

After World War II, there were major cutbacks, such that units responding early in the Korean War under United Nations authority (e.g., Task Force Smith) were unprepared, resulting in catastrophic performance. It should be noted that when Harry S. Truman fired Douglas MacArthur, the tradition of civilian control held and MacArthur left without any hint of military coup.

The Cold War resulted in serious permanent military buildups. Dwight D. Eisenhower, a retired top military commander elected as a civilian President, warned, as he was leaving office, of the development of a military-industrial complex.[13] In the Cold War, there emerged many civilian academics and industrial researchers, such as Henry Kissinger and Herman Kahn, who had significant input into the use of military force. The complexities of nuclear strategy and the debates surrounding them helped produce a new group of 'defense intellectuals' and think tanks, such as the Rand Corporation (where Kahn, among others, worked).[14]

It has been argued that the United States has shifted to a state of neomilitarism since the end of the Vietnam War. This form of militarism is distinguished by the reliance on a relatively small number of volunteer fighters; heavy reliance on complex technologies; and the rationalization and expansion of government advertising and recruitment programs designed to promote military service.[15]

The direct military budget of the United States for 2008 was $740,800,000,000.[16]

Venezuela

Militarism in Venezuela follows the cult and myth of Simón Bolívar, known as the liberator of Venezuela.[17] For much of the 1800s, Venezuela was ruled by powerful, militarists leaders known as caudillos.[18] Between 1892 and 1900 alone, six rebellions occurred and 437 military actions were taken to obtain control of Venezuela.[18] With the military controlling Venezuela for much of its history, the country practiced a "military ethos", with civilians today still believing that military intervention in the government is positive, especially during times of crisis, with many Venezuelans believing that the military opens democratic opportunities instead of blocking them.[18]

Much of the modern political movement behind the Fifth Republic of Venezuela, ruled by the Bolivarian government established by Hugo Chávez, was built on the following of Bolívar and such militaristic ideals.[17] Chávez often used Bolivarian propaganda to glorify the military, with Manuel Anselmi explaining in Chávez's Children: Ideology, Education, and Society in Latin America, that "To get an idea of the importance of Bolivarian propaganda as a source of alternative political education one can use the testimony of Hugo Chávez himself". Chávez explained how he had "read the classics of socialism and of military theory and study the possible role of the army in a democratic popular revolt".[19] In 1999 following the election of Hugo Chávez into the presidency, author Carlos Alberto Montaner described Chávez "as the new Venezuelan caudillo who would reformulate Venezuelan politics at his will".[18]

As Chávez took power of Venezuela, his influencer, left-wing Argentine sociologist Norberto Ceresole, helped Chávez establish the Bolivarian movement in the shadow of Simón Bolívar's following, with Ceresole stating that:[17]

All of these elements ... a military leader becoming a strong man or national head, the absence of effective, intermediary civilian institutions, the presence of an important group of "apostles" that intervene with generosity and magnanimity between the strong man and the masses ... comprise a model of change — in truth, a revolutionary model — that is absolutely new, although in line with clear historical traditions.

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, under the Chávez presidency between 2004 and 2008, Venezuela moved from 55th place in arms importing to 18th, acquiring nearly $2 billion worth of weaponry from Russia. Domingo Alberto Rangel, founder of the Marxist Venezuelan political Revolutionary Left Movement, explained that Chávez's description of a movement being "Bolivarian" and "socialist" was contradictory, saying this "is tolerated and continues because the regime is both military and militaristic. ... Those who monopolize the decision in this regime are military men".[17]

Chávez's handpicked successor, Nicolás Maduro, relied on the military to maintain power when he was elected into office, with Luis Manuel Esculpi, a Venezuelan security analyst, stating that "The army is Maduro's only source of authority."[20] Maduro grew more reliant on the military through his presidency, showing that Maduro was losing power as described by Amherst College professor, Javier Corrales.[21] Corrales explains that "From 2003 until Chavez died in 2013, the civilian wing was strong, so he did not have to fall back on the military. As civilians withdrew their support, Maduro was forced to resort to military force."[21] The New York Times states that Maduro no longer had the oil revenue to buy loyalty for protection, instead relying on favorable exchange rates, as well as the smuggling of food and drugs, which "also generate revenue" for troops.[22]

See also

References

- ↑ New Oxford American Dictionary (2007)

- ↑ "Militaristic - definition of militaristic by The Free Dictionary". TheFreeDictionary.com.

- ↑ Srinath Raghavan, 1971: A Global History of the Creation of Bangladesh (Harvard Univ. Press, 2013).

- ↑ George Perkovich, India's Nuclear Bomb (Univ. of California Press, 2001).

- ↑ "Strengths and Weaknesses in the Decision-Making Process" Craig AM in Vogel, EM (ed.), Modern Japanese Organization and Decision-Making, University of California Press, 1987.

- ↑ Vorontsov, Alexander V (26 May 2006). "North Korea's Military-First Policy: A Curse or a Blessing?". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 31 May 2006. Retrieved 26 March 2007.

- ↑ New Challenges of North Korean Foreign Policy By K. Park

- ↑ Jae Kyu Park, "North Korea since 2000 and prospects for Inter Korean Relations" Korea.net, 19 January 2006, <http://www.korea.net/News/Issues/IssueDetailView.asp?board_no=11037> 12 May 2007.

- ↑ "Militarism in the Philippines:".

- ↑ Fareed Zakaria, From Wealth to Power: The Unusual Origins of America's World Role (Princeton Univ. Press, 1998), chap.4.

- ↑ Richard Hofstadter (1992). Social Darwinism in American Thought. Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-5503-8.

- ↑ Spencer Tucker (2009). The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-951-1.

- ↑ Audra J. Wolfe, Competing with the Soviets: Science, Technology, and the State in Cold War America (Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 2013), chap.2.

- ↑ Fred Kaplan, The Wizards of Armageddon (1983, reissued 1991).

- ↑ Roberts, Alasdair. The Collapse of Fortress Bush: The Crisis of Authority in American Government. New York: New York University Press, 2008, 14 and 108–117.

- ↑

- 1 2 3 4 Uzcategui, Rafael (2012). Venezuela: Revolution as Spectacle. See Sharp Press. pp. 142–149. ISBN 9781937276164.

- 1 2 3 4 Block, Elena (2015). Political Communication and Leadership: Mimetisation, Hugo Chavez and the Construction of Power and Identity. Routledge. pp. 74–91. ISBN 9781317439578.

- ↑ Anselmi, Manuel (2013). Chávez's children : ideology, education, and society in Latin America. p. 44. ISBN 978-0739165256.

- 1 2 Kurmanaev, Anatoly (12 July 2016). "Venezuelan President Puts Armed Forces in Charge of New Food Supply System". Dow Jones & Company, Inc. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- 1 2 Usi, Eva (14 July 2016). "Vladimir Padrino: el hombre fuerte de Venezuela". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ↑ Taub, Amanda; Fisher, Max (6 May 2017). "In Venezuela's Chaos, Elites Play a High-Stakes Game for Survival". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

Further reading

- Bacevich, Andrew J. The New American Militarism. Oxford: University Press, 2005.

- http://www.elib.gov.ph/results.php?f=subject&q=Militarism+--+Philippines

- Barr, Ronald J. "The Progressive Army: US Army Command and Administration 1870–1914." St. Martin's Press, Inc. 1998. ISBN 0-312-21467-7.

- Barzilai, Gad. Wars, Internal Conflicts and Political Order. Albany: State University of New York Press. 1996.

- Bond, Brian. War and Society in Europe, 1870–1970. McGill-Queen's University Press. 1985 ISBN 0-7735-1763-4

- Conversi, Daniele 2007 'Homogenisation, nationalism and war’, Nations and Nationalism, Vol. 13, no 3, 2007, pp. 1–24

- Ensign, Tod. America's Military Today. The New Press. 2005. ISBN 1-56584-883-7.

- Fink, Christina. Living Silence: Burma Under Military Rule. White Lotus Press. 2001. ISBN 1-85649-925-1.

- Frevert, Ute. A Nation in Barracks: Modern Germany, Military Conscription and Civil Society. Berg, 2004. ISBN 1-85973-886-9

- Huntington, Samuel P.. Soldier and the State: The Theory and Politics of Civil-Military Relations. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1981.

- Ritter, Gerhard The Sword and the Scepter; the Problem of Militarism in Germany, translated from the German by Heinz Norden, Coral Gables, Fla., University of Miami Press 1969–73.

- Shaw, Martin. Post-Military Society: Militarism, Demilitarization and War at the End of the Twentieth Century. Temple University Press, 1992.

- Tang, C. Comprehensive Notes on World History Hong Kong, 2004

- Vagts, Alfred. A History of Militarism. Meridian Books, 1959.

- Western, Jon. Selling Intervention and War. Johns Hopkins University . 2005. ISBN 0-8018-8108-0

- http://www.india-seminar.com/2010/611/611_sunil_&_stephen.htm