Working class

The working class (also labouring class) are the people employed for wages, especially in manual-labour occupations and industrial work.[1] Working-class occupations include blue-collar jobs, some white-collar jobs, and most pink-collar jobs. The working class only rely upon their earnings from wage labour, thereby, the category includes most of the working population of industrialized economies, of the urban areas (cities, towns, villages) of non-industrialized economies, and of the rural workforce.

In Marxist theory and socialist literature, the term working class is often used interchangeably with the term proletariat, and includes all workers who expend both physical and mental labour (salaried knowledge workers and white-collar workers) to produce economic value for the owners of the means of production (the bourgeoisie in Marxist literature).[2]

Definitions

As with many terms describing social class, working class is defined and used in many different ways. The most general definition, used by Marxists and socialists, is that the working class includes all those who have nothing to sell but their labor-power and skills. In that sense it includes both white and blue-collar workers, manual and mental workers of all types, excluding only individuals who derive their income from business ownership and the labor of others.[3]

When used non-academically in the United States, however, it often refers to a section of society dependent on physical labor, especially when compensated with an hourly wage. For certain types of science, as well as less scientific or journalistic political analysis, for example, the working class is loosely defined as those without college degrees.[4] Working-class occupations are then categorized into four groups: Unskilled laborers, artisans, outworkers, and factory workers.[5]

A common alternative, sometimes used in sociology, is to define class by income levels. When this approach is used, the working class can be contrasted with a so-called middle class on the basis of differential terms of access to economic resources, education, cultural interests, and other goods and services. The cut-off between working class and middle class here might mean the line where a population has discretionary income, rather than simply sustenance (for example, on fashion versus merely nutrition and shelter).

Some researchers have suggested that working-class status should be defined subjectively as self-identification with the working-class group.[6] This subjective approach allows people, rather than researchers, to define their own social class.

History and growth

In feudal Europe, the working class as such did not exist in large numbers. Instead, most people were part of the laboring class, a group made up of different professions, trades and occupations. A lawyer, craftsman and peasant were all considered to be part of the same social unit, a third estate of people who were neither aristocrats nor church officials. Similar hierarchies existed outside Europe in other pre-industrial societies. The social position of these laboring classes was viewed as ordained by natural law and common religious belief. This social position was contested, particularly by peasants, for example during the German Peasants' War.[7]

In the late 18th century, under the influence of the Enlightenment, European society was in a state of change, and this change could not be reconciled with the idea of a changeless god-created social order. Wealthy members of these societies created ideologies which blamed many of the problems of working-class people on their morals and ethics (i.e. excessive consumption of alcohol, perceived laziness and inability to save money). In The Making of the English Working Class, E.P. Thompson argues that the English working class was present at its own creation, and seeks to describe the transformation of pre-modern laboring classes into a modern, politically self-conscious, working class.[8]

Starting around 1917, a number of countries became ruled ostensibly in the interests of the working class. (see Soviet working class). Some historians have noted that a key change in these Soviet-style societies has been a massive a new type of proletarianisation, often effected by the administratively achieved forced displacement of peasants and rural workers. Since then, four major industrial states have turned towards semi-market-based governance (China, Laos, Vietnam, Cuba), and one state has turned inwards into an increasing cycle of poverty and brutalisation (North Korea). Other states of this sort have either collapsed (such as the Soviet Union), or never achieved significant levels of industrialization or large working classes.[9]

Since 1960, large-scale proletarianisation and enclosure of commons has occurred in the third world, generating new working classes. Additionally, countries such as India have been slowly undergoing social change, expanding the size of the urban working class.[10]

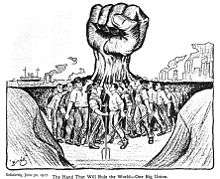

Marxist definition: the proletariat

Karl Marx defined the working class or proletariat as individuals who sell their labour power for wages and who do not own the means of production. He argued that they were responsible for creating the wealth of a society. He asserted that the working class physically build bridges, craft furniture, grow food, and nurse children, but do not own land, or factories.[11]

A sub-section of the proletariat, the lumpenproletariat (rag-proletariat), are the extremely poor and unemployed, such as day laborers and homeless people. Marx considered them to be devoid of class consciousness.

In The Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels argued that it was the destiny of the working class to displace the capitalist system, with the dictatorship of the proletariat, abolishing the social relationships underpinning the class system and then developing into a future communist society in which "the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all." Some issues in Marxist arguments about working-class membership have included:

- The class status of people in a temporary or permanent position of unemployment.

- The class status of domestic labor, particularly the children (see child labour), and also traditionally the wives of male workers, as some spouses do not themselves work in paying jobs outside the home.

- Whether workers can be considered working class if they own personal property or small amounts of stock ownership.

- The relationships among peasants, rural smallholders, and the working class.

- The extent to which non-class group identities and politics (race, gender, et al.) can obviate or substitute for working-class membership in Enlightenment projects, where working-class membership is prohibitively contradictory or obfuscated.

Possible responses to some of these issues are:

- Unemployed workers are proletariat.

- Class for dependents is determined by the primary income earner.

- Personal property is argued to be different from private property. For example, the proletariat can own automobiles; this is personal property.

- The self-employed worker may be a member of the petite bourgeoisie (for example, a small store owner who controls little capital), or a de facto member of the proletariat (for example, a contract worker whose income may be relatively high, but is precarious and tied to the need to sell one's labor on the labor market).

In general, in Marxist terms, wage laborers and those dependent on the welfare state are working class, and those who live on accumulated capital are not. This broad dichotomy defines the class struggle. Different groups and individuals may at any given time be on one side or the other. For example, retired factory workers are working-class in the popular sense; but to the extent that they live off fixed incomes, financed by stock in corporations whose earnings are profit, retired factory workers' interests, and possibly their identities and politics, are not working class. Such contradictions of interests and identity within individuals' lives and within communities can effectively undermine the ability of the working class to act in solidarity to reduce exploitation, inequality, and the role of ownership in determining people's life chances, work conditions, and political power.

See also

- Apprentice

- Designation of workers by collar color

- Embourgeoisement

- Globalization

- Household income in the United States

- Industrial novel

- Knowledge worker

- Labour movement

- Living wage and Minimum wage

- Proletarian literature

- Proletarian novel

- Social class

- Social mobility

- Trade union

- US working class

- Vocational education

- Wage slavery

- Working class culture

References

- ↑ working class. Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ↑ Martin Glaberman (17 September 1974). "Marxist Views of the Working Class". Marxists.org. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- ↑ Ross McKibbin, Classes and Cultures: England 1918-1951(2000) p. 164.

- ↑ Thomas B. Edsall (June 17, 2012). "Canaries in the CoaMine" (Blog by expert). The New York Times. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- ↑ Doob, B. Christopher (2013). Social Inequality and Social Stratification in US Society. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education. ISBN 0-205-79241-3.

- ↑ Rubin, M. (2014). ""I Am Working-Class": Subjective Self-Definition as a Missing Measure of Social Class and Socioeconomic Status in Higher Education Research". Educational Researcher. 43 (4): 196–200. doi:10.3102/0013189X14528373.

- ↑ Wolfgang Abendroth, A Short History of the European Working Class (1973)

- ↑ Wolfgang Abendroth, A Short History of the European Working Class (1973)

- ↑ Hiroaki Kuromiya. Stalin's Industrial Revolution: Politics and Workers, 1928-1931 (1990) P. 87

- ↑ Peter Claus and Wolfgang Gutkind, eds. Third Worlds Workers: Comparative International Labour Studies (1988).

- ↑ Michael A. Lebowitz, Beyond Capital: Marx’s Political Economy of the Working Class (2016)

Further reading

- Benson, John. The Working Class in Britain 1850-1939 (IB Tauris, 2003)

- Blackledge, Paul (2011). "Why workers can change the world". Socialist Review 364. London.

- Connell, Raewyn & Irving, Terry, Class Structure in Australian History, Longman Cheshire (1980), Melbourne.

- Engels, Friedrich, Condition of the Working Class in England [in 1844], Stanford University Press (1968), trade paperback, ISBN 0-8047-0634-4 Numerous other editions exist; first published in German in 1845. Better editions include a preface written by Engels in 1892.

- Miles, Andrew, and Mike Savage. (2013) The remaking of the British working class, 1840-1940 (Routledge, 2013).

- Moran, W. (2002). Belles of New England: The women of the textile mills and the families whose wealth they wove. New York: St Martin's Press, ISBN 0-312-30183-9.

- Raine, April Janise. "Lifestyles of the Not So Rich and Famous: Ideological Shifts in Popular Culture, Reagan-Era Sitcoms and Portrayals of the Working Class." McNair Scholars Research Journal 7#1 (2011): 63-78 online, With bibliographical citations

- Rose, Jonathan, The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes. (Yale University Press, 2001)

- Rubin, Lillian Breslow, Worlds of Pain: Life in the Working Class Family, Basic Books (1976), 268 pages, ISBN 0-465-09724-3

- Sheehan, Steven T. "'Pow! Right in the Kisser': Ralph Kramden, Jackie Gleason, and the Emergence of the Frustrated Working‐Class Man". Journal of Popular Culture 43#3 (2010): 564-582.

- Shipler, David K., The Working Poor: Invisible in America, Knopf (2004), hardcover, 322 pages, ISBN 0-375-40890-8

- Skeggs, Beverley. Class, Self, Culture, Routledge, (2004),

- Thompson, E.P, The Making of the English Working Class - paperback Penguin.

- Turner, Katherine Leonard. How the Other Half Ate: A History of Working-Class Meals at the Turn of the Century. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2014.

- Zweig, Michael, Working Class Majority: America's Best Kept Secret, Cornell University Press (2001), trade paperback, 198 pages, ISBN 0-8014-8727-7

External links

| Look up working class in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- The Center for Working-Class Studies at Youngstown State University

- International Labor and Working-Class History Journal

- Images of the working class between 1840 and 1945 from the McCord Museum's online collection

- The Working-Class poetry of Gerald Massey

- Definition of "Working Class", Dictionary.com

- An introduction to the working class, Prole.info

- [http://socserv.mcmaster.ca/labourstudies/graduate/gradPDF/ResourcesWS700.pdf Bibliography - Work, Workers and their Workplaces]

- Working Moms

- List of Working Class Literature

- List of Working Class Videos — Movies, and Documentaries

- Paulo Freire Research Center–Finland

- BBC Archive collection of TV & Radio programmes about Working Class Britain

- Caring too much. That's the curse of the working classes. David Graeber for The Guardian. March 2014.

- US millennials feel more working class than any other generation. The Guardian. March 2016.

.svg.png)