Lurgan

Lurgan

| |

|---|---|

A statue of linen-makers in Lurgan town centre. | |

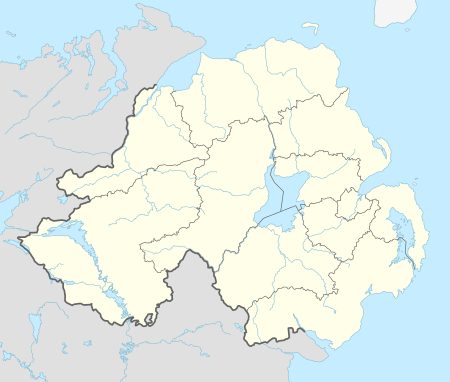

Lurgan Lurgan shown within Northern Ireland | |

| Population | 25,069 (estimate based on 2001 Census, see below) |

| Irish grid reference | J080585 |

| • Belfast | 18 miles (29 km)[1] |

| District | |

| County | |

| Country | Northern Ireland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | CRAIGAVON |

| Postcode district | BT66, BT67 |

| Dialling code | 028 |

| Police | Northern Ireland |

| Fire | Northern Ireland |

| Ambulance | Northern Ireland |

| EU Parliament | Northern Ireland |

| UK Parliament | |

| NI Assembly | |

| Website | www.lurgan-forward.com |

Lurgan (from Irish: An Lorgain, meaning "the shin-shaped hill") is a town in County Armagh, Northern Ireland. The town is near the southern shore of Lough Neagh and is in the north-eastern corner of County Armagh. Lurgan is about 18 miles (29 km) south-west of Belfast and is linked to the city by both the M1 motorway and the Belfast–Dublin railway line. It had a population of about 23,000 at the 2001 Census. It is within the Armagh, Banbridge and Craigavon district.

Lurgan is characteristic of many Plantation of Ulster settlements, with its straight, wide planned streets and rows of cottages. It is the site of a number of historic listed buildings including Brownlow House and the former town hall.

Historically the town was known as a major centre for the production of textiles (mainly linen) after the industrial revolution and it continued to be a major producer of textiles until that industry steadily declined in the 1990s and 2000s. The development of the 'new city' of Craigavon had a major impact on Lurgan in the 1960s when much industry was attracted to the area. The expansion of Craigavon's Rushmere Retail Park in the 2000s has affected the town's retail trade further.

History

.jpg)

.jpg)

The name Lurgan is an anglicisation of the Irish name An Lorgain. This literally means "the shin", but in placenames means a shin-shaped hill or ridge (i.e. one that is long, low and narrow). Earlier names of Lurgan include Lorgain Chlann Bhreasail (anglicised Lurganclanbrassil, meaning "shin-shaped hill of Clanbrassil") and Lorgain Bhaile Mhic Cana (anglicised Lurganvallivackan, meaning "shin-shaped hill of McCann's settlement").[2] The McCanns were a sept of the O'Neills and Lords of Clanbrassil before the Plantation of Ulster period in the early 17th century.[3]

About 1610, during the Plantation and at a time when the area was sparsely populated by Irish Gaels,[3] the lands of Lurgan were granted to the English lord William Brownlow and his family. Initially the Brownlow family settled near the lough at Annaloist, but by 1619, on a nearby ridge, they had established a castle and bawn for their own accommodation, and "a fair Town, consisting of 42 Houses, all of which are inhabited with English Families, and the streets all paved clean through also to water Mills, and a Wind Mill, all for corn."[4]

Brownlow became MP for Armagh in the Irish Parliament in 1639. During the Irish Rebellion of 1641, Brownlow's castle and bawn were destroyed, and he and his wife and family were taken prisoner and brought to Armagh and then to Dungannon in County Tyrone.[5] The land was then passed to the McCanns and the O'Hanlons. In 1642, Brownlow and his family were released by the forces of Lord Conway, and as the rebellion ended they returned to their estate in Lurgan. William Brownlow died in 1660, but the family went on to contribute to the development of the linen industry which peaked in the town in the late 17th century.[6]

Theobald Wolfe Tone would often pass through Lurgan on his journeys, writing in 1792 "Lurgan green as usual".[7]

An Gorta Mór/The Great Hunger

A workhouse was built in Lurgan and opened in 1841 under the stipulations of the Poor Law which stated that each Poor Law Union would build a workhouse to give relief to the increasing numbers of destitute poor. In 1821 the population of Lurgan was 2,715, this increased to 4,677 by 1841. There were a couple of reasons for this large growth in population. Firstly the opportunities provided by the booming linen industry led many to abandon their meagre living in rural areas and migrate to Lurgan in the hope of gaining employment. Secondly the ever-expanding town gave tradesmen the opportunity to secure work in the construction of new buildings such as Brownlow House.

The large numbers of poor workers migrating to the town inevitably resulted in over-crowding and a very low standard of living. When the potato crop failed for a second time in 1846 the resulting starvation led to a quickly overcrowded workhouse which by the end of 1846 exceeded its 800 capacity. In an attempt to alleviate the problem a relief committee was established in Lurgan as they were in other towns. The relief committees raised money by subscription from local landowners, gentry and members of the clergy and were matched by funds from Dublin. With these monies food was bought and distributed to the ever-increasing numbers of starving people at soup kitchens. In an attempt to provide employment and thereby give the destitute the means to buy food, Lord Lurgan devised a scheme of land- drainage on his estate.

The so-called 'famine roads' were not built in Lurgan to the same extent as the rest of Ireland, although land owners also provided outdoor relief by employing labourers to lower hills and repair existing road. During the period 1846 to 1849 the famine claimed 2,933 lives in the Lurgan Union alone. The Lurgan workhouse was situated in the grounds of what is now Lurgan Hospital and a commemorative mural can be seen along the adjacent Tandragee Road.[8]

New city

The town grew steadily over the centuries as an industrial market town, and in the 1960s, when the UK government was developing a programme of new towns in Great Britain to deal with population growth, the Northern Ireland government also planned a new town to deal with the projected growth of Belfast and to prevent an undue concentration of population in the city. Craigavon (a name unpopular with the Nationalist community) was designated as a new town in 1965, intended to be a linear city incorporating the neighbouring towns of Lurgan and Portadown. The plan largely failed,[9] and today, 'Craigavon' locally refers to the rump of the residential area between the two towns.[10] The Craigavon development, however, did affect Lurgan in a number of ways. The sort of dedicated bicycle and pedestrian paths that were built in Craigavon were also incorporated into newer housing areas in Lurgan, additional land in and around the town was zoned for industrial development, neighbouring rural settlements such as Aghacommon and Aghagallon were developed as housing areas, and there was an increase in the town's population, although not on the scale that had been forecast.

The textile industry remained a main employer in the town until the late twentieth century, with the advent of access to cheaper labour in the developing world leading to a decline in the manufacture of clothing in Lurgan.[11]

The Troubles

Lurgan and the associated towns of Portadown and Craigavon made up part of what was known as the "murder triangle"; an area known for a significant number of incidents and fatalities during The Troubles.[12] Today the town is one of the few areas in Northern Ireland where so-called dissident republicans have a significant level of support.[13] The legacy of the Troubles is continued tension between Roman Catholics and Protestants, which has occasionally erupted into violence at flashpoint 'interface areas'.[14]

On the 5 March 1992, a 1,000 lb truck bomb, believed to have been planted by the IRA, exploded in Main Street causing mass damage to commercial properties.[15]

Geography

Lurgan sits in a relatively flat part of Ireland by the south east shore of Lough Neagh. The two main formations in north Armagh are an area of estuarine clays by the shore of the lough, and a mass of basalt farther back. The earliest human settlements in the area were to the northwest of the present day town near the shore of the lough. When the land was handed to the Brownlow family, they initially settled near the lough at Annaloist, but later settled where the town was eventually built.[4] The oldest part of the town, the main street, is built on a long ridge in the townland (baile fearainn) of Lurgan. A neighbouring hill is the site of Brownlow House, which overlooks Lurgan Park.

Townlands

Like the rest of Ireland, the Lurgan area has long been divided into townlands, whose names mostly come from the Irish language. Lurgan sprang up in the townland of the same name. Over time, the surrounding townlands have been built upon and they have given their names to many roads and housing estates. The following is a list of townlands within Lurgan's urban area, alongside their likely etymologies:[16][17][18][19]

Shankill parish:

- Aghnacloy (from Irish Achadh na Cloiche, meaning 'field of the stone')

- Ballyblagh (from Baile Bláthach meaning "flowery townland")

- Ballyreagh (from Baile Riach meaning "greyish townland")

- Demesne (an English name – this townland was carved out of Drumnamoe and others)

- Derry (from Doire meaning "oak grove")

- Dougher or Doughcorran (from Dúchorr meaning "black round hill" and Dúchorrán meaning "small black round hill")

- Drumnamoe (from Druim na mBó meaning "ridge of the cows" or Druim na Mothar meaning "ridge of the thickets")

- Knocknashane (formerly Knocknashangan, from Cnoc na Seangán meaning "hill of the ants")

- Shankill (from Seanchill meaning "old church" or Seanchoill meaning "old wood")

- Taghnevan (formerly Tegnevan, from Teach Naomháin meaning "Naomhán's house")

- Tannaghmore North & Tannaghmore South (from an Tamhnach Mór meaning "the big grassland")

- Toberhewny (from Tobar hAoine/Tobar Chainnigh/Tobar Shuibhne meaning "Friday well/Canice's well/Sweeny's well")

Seagoe parish:

- Aghacommon (from Achadh Camán meaning "hurling field")

- Ballynamony (from Baile na Móna meaning "townland of the bog")

- Silverwood (an English name – formerly called Killinargit, from Coill an Airgid meaning "wood of the silver")

Climate

Lurgan has a temperate climate in common with inland areas in Ireland. Summer temperatures can reach the 20s °C and it is rare for them to go higher than 30 °C (86 °F). The consistently humid climate that prevails over Ireland can make temperatures feel uncomfortable when they stray into the high 20s °C (80–85 °F), more so than similar temperatures in hotter climates in the rest of Europe.

| Climate data for Lurgan | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7 (45) |

8 (46) |

10 (50) |

12 (54) |

15 (59) |

17 (63) |

19 (66) |

19 (66) |

16 (61) |

13 (55) |

10 (50) |

7 (45) |

13 (55) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2 (36) |

2 (36) |

3 (37) |

4 (39) |

6 (43) |

9 (48) |

11 (52) |

10 (50) |

9 (48) |

7 (45) |

4 (39) |

3 (37) |

6 (43) |

| Average precipitation cm (inches) | 5.6 (2.2) |

4.67 (1.839) |

4.46 (1.756) |

4.62 (1.819) |

4.22 (1.661) |

4.38 (1.724) |

4.49 (1.768) |

4.84 (1.906) |

4.58 (1.803) |

6.79 (2.673) |

5.94 (2.339) |

5.61 (2.209) |

60.2 (23.697) |

| Source: MSN.com[20] | |||||||||||||

Governance

Lurgan is part of the Upper Bann constituency for the purpose of elections to the UK Parliament at Westminster. This has long been a safe unionist seat[21] and the current MP is David Simpson of the Democratic Unionist Party.

Members of the Northern Ireland Assembly at Stormont are elected from six-member constituencies using proportional representation and using the same constituencies as for Westminster.

Lurgan town commissioners were first elected in 1855,[22] and they were replaced by Lurgan Urban District Council following the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898. This effectively ended landlord control of local government in Ireland.[23][24][25] The town council was abolished when local government was reformed in Northern Ireland in 1973 under the Local Government (Boundaries) Act (Northern Ireland) 1971 and the Local Government Act (Northern Ireland) 1972. These abolished the two-tier system of town and county councils replacing it with the single-tier system. Lurgan was placed under the jurisdiction of Craigavon Borough Council, and remained so until a new act streamlined and merged the various districts in 2015. Today Lurgan forms part of the new Armagh, Banbridge and Craigavon District. The Lurgan area contains the following wards: Church, Donaghcloney, Knocknashane, Magheralin, Mourneview, Parklake, and Waringstown.

Lurgan Town Hall is owned by the new District Council but has not been used to conduct Council business since the Town Council was abolished in 1972.

Demography

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1821 | 2,715 | — |

| 1831 | 2,842 | +4.7% |

| 1841 | 4,677 | +64.6% |

| 1851 | 4,205 | −10.1% |

| 1861 | 7,772 | +84.8% |

| 1871 | 10,632 | +36.8% |

| 1881 | 10,135 | −4.7% |

| 1891 | 11,429 | +12.8% |

| 1901 | 11,782 | +3.1% |

| 1911 | 12,553 | +6.5% |

| 1926 | 12,500 | −0.4% |

| 1937 | 13,766 | +10.1% |

| 1951 | 16,183 | +17.6% |

| 1961 | 17,872 | +10.4% |

| 1966 | 20,673 | +15.7% |

| 1971 | 25,431 | +23.0% |

| 1981 | 20,991 | −17.5% |

| 1991 | 21,905 | +4.4% |

| 2001 | 23,534 | +7.4% |

| [26][27][28][29][30][31][32] | ||

For census purposes, Lurgan is not treated as a separate entity by the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA). Instead, it is combined with Craigavon, Portadown and Bleary to form the "Craigavon Urban Area". A fairly accurate population count can be found by combining the data of the electoral wards that make up the Lurgan urban area. These are Church,[33] Court,[34] Drumnamoe,[35] Knocknashane,[36] Mourneview,[37] Parklake,[38] Taghnevan[39] and Woodville.[40]

On the day of the last census (27 March 2011) the combined population of these wards was 25,093

Of this population:

15,607(62.2%) were Nationalist (Catholic or from a Catholic background)

8,460(33.7%) were Unionist (Protestant or from a Protestant background)

1,026(4.1%) were of other ethno-religious backgrounds or no religious background.

The town is divided along ethnic/political/sectarian lines with entire housing areas being almost exclusively Nationalist/Catholic/Irish or almost exclusively Unionist/Protestant/British settler.[41] The north end of the town centre is considered Nationalist/Catholic, the south end is considered Unionist/Protestant, with the "invisible dividing line" crossing Market Street at Castle Lane and Carnegie Street.[42] In the 1980s there were two Unionist/Protestant enclaves in the north end of the town, Gilpinstown and Wakehurst. They have both since changed to become Nationalist/Catholic areas as Unionists/Protestants gradually moved out.[42]

There was a Synagogue at 49 North Street for the Lurgan Hebrew Congregation, founded prior to 1906 by Joseph Herbert (originally Herzberg) from Tukums in Latvia, but this closed in the 1920s around the time of the founder's death.

Economy

Lurgan has historically been an industrial town in which the linen industry predominated as a source of employment during the Industrial Revolution, and is said to have employed as many as 18,000 handloom weavers at the end of the 19th century, a figure significantly higher than the town's resident population at the time.[43] That particular branch of the textile industry declined as consumer tastes changed, but other textiles continued to be produced in the town providing a major source of employment until the 1990s and 2000s[11] when the textile industry across the UK suffered a major decline as a result of outsourcing to low wage countries.[44]

The large Goodyear fan-belt factory at Silverwood Industrial Estate was a product of the Craigavon development when large tracts of land in Lurgan, Portadown, and areas in between were zoned off for exclusive industrial use. The Goodyear factory closed in 1983 after failing to make a profit, resulting in the loss of 750 jobs.[45] The facility was later partly occupied by Wilson Double Deck Trailers and DDL Electronics. Silverwood Industrial Estate continues to host other manufacturing and light engineering firms. Other industrial areas in the town are Annesborough and Halfpenny Valley (Portadown Road) industrial estates; areas in which growth has been limited compared to other industrial estates in the Craigavon Borough.[46]

A key component of the Craigavon development was a central business district halfway between Lurgan and Portadown that would serve as the city centre for the whole of the new city. What was built was an office building, a court house, a civic building, and a small shopping centre alongside several acres of parkland that were developed around the newly created balancing lakes that also serve as part of the area's drainage system. In the 1990s, the shopping centre was significantly expanded to form what is now Rushmere Retail Park, containing many major retail stores. This has had a detrimental effect on the retail trade in Lurgan in the same way that out-of-town shopping developments in other parts of Northern Ireland have damaged other traditional town centres.[47] The town's Chamber of Commerce is not functioning and has remained dormant despite numerous attempts to revive it.[48]

Culture and community

Cultural references

There is a figure of speech used in Ireland – to have a face as long as a Lurgan spade – meaning "to look miserable".[49] The origins of this expression are disputed. One theory is that a "Lurgan spade" was an under-paid workman digging what is now the Lurgan Park lake.[5] Another theory is that it could be from the Irish language lorga spád meaning the shaft (literally "shin") of a spade.

The ballad Master McGrath concerns a greyhound of that name from Lurgan which became an Irish sporting hero. The dog was bought in Lurgan by the Brownlow family, and the song also mentions his owner Charles Brownlow, referred to in the lyrics as Lord Lurgan. Master McGrath won the Waterloo Cup hare coursing competition three times in 1868, 1870 and 1871 at a time when this was a high-profile sport. A post mortem found that he had a heart twice the size of what is normal for a dog of his size.[50] He is remembered all over the town, including in its coat of arms. The dog was named McGrath after the kennel boy responsible for its care. A statue of him was unveiled at Craigavon Civic Centre in 1993, over 120 years after his last glory in 1871. The statue was relocated to Lurgan town centre in 2013. A festival is also held yearly in his honour. A Lurgan pub was also named after Master McGrath, although it has been renamed in recent years.

The town is a frequent recipient of derision by the BBC Northern Ireland comedy panel show The Blame Game.

Community facilities

Oxford Island is a nature reserve on the shore of Lough Neagh that includes Kinnego Marina and the Lough Neagh Discovery Center, which is an interpretive visitor centre offering information about the surrounding wildlife, conference facilities, and a café.[51]

Lurgan Park, a few hundred yards from the main street, is the largest urban park in Northern Ireland[52] and the second-largest in Ireland after Phoenix Park, Dublin. It used to be part of the estate of Brownlow House, a 19th-century Elizabethan-style manor house.[53] In 1893, the land was purchased by Lurgan Borough Council and opened as a public park in 1909 by Earl Aberdeen, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.[54] It includes a sizeable artificial lake and an original Coalbrookdale fountain. Today the park is home to annual summer events such as the Lurgan Agricultural Show, and the Lurgan Park Rally, noted as the largest annual motor sport event in Northern Ireland and a stage in the Circuit of Ireland rally. Mount Zion House in Edward St, formerly the St Joseph's Convent, is now a cross-community centre run by the Shankill Lurgan Community Association/Community Projects. It is funded by the Department for Social Development, the EU Special Programme for Peace and Reconciliation, and the Physical and Social Environment Programme.[55]

Landmarks

Lurgan town centre is distinctive for its wide main street, Market Street, one of the widest in Ireland, which is dominated at one end by Shankill (Anglican) Church in Church Place. A grey granite hexagonal temple-shaped war memorial sits at the entrance to Church Place, topped by a bronze-winged statue representing the spirit of Victorious Peace. A marble pillar at the centre displays the names of over 400 men from the town who lost their lives in the First World War.[56]

The rows of buildings on either side of Market Street are punctuated periodically by large access gates that lead to the space behind the buildings, gates that are wide enough to drive a horse and cart through. The town's straight planned streets are a common feature in many Plantation towns, and its industrial history is still evident in the presence of many former linen mills that have since been modified for modern use.

At the junction of Market Street and Union Street is the former Lurgan Town Hall, a listed building erected in 1868. It was the first site of the town's library in 1891,[57] was temporarily used as a police station in 1972 when it was handed to the Police Authority,[58] and is today owned by the Mechanics' Institute and is available for conferences and community functions.[59]

Brownlow House, known locally as 'Lurgan Castle', is a distinctive mansion built in 1833 with Scottish sandstone in an Elizabethan style with a lantern-shaped tower and prominent array of chimney pots. It was originally owned by the Brownlow family, and today is owned by the Lurgan Loyal Orange District Lodge. A former lodge to the Brownlow House estate became the Brownlow Arms Hotel on Market Street, run by the McCaffrey family, which served as the US 5th Army's Officers' Mess during WW2 but closed in the early 1960s. The adjacent Lurgan Park, now a public park owned by Craigavon Borough Council, used to be part of the same estate.[60] The park is the venue for the Lurgan Park Rally.

Religious sites

The site of what is now Shankill cemetery served as a place of worship over the centuries. It began in ancient times as a simple double ring fort, the outline of which is still noticeable,[61] and is today an historic burial site holding the remains of people who lived in the earliest days of the town's existence, including the Brownlow family. Dougher cemetery is another old graveyard that was donated to the Catholic people by the Brownlows following passage of the Catholic Relief Act.[62]

The two most prominent modern places of worship are Shankill Parish Church in Church Place and St Peter's Church in North Street, the steeples of which are visible from far outside the town.

Shankill Parish Church belongs to the Anglican Church of Ireland. The original church was established at Oxford Island on the shore of Lough Neagh in 1411, but a new church was built in Lurgan on the site of what is now Shankill Cemetery in 1609 as the town became the main centre of settlement in the area.[63] It was eventually found to be too small given the growth of the town, and the Irish Parliament granted permission to build a replacement in 1725 one mile away on the 'Green of Lurgan', now known as Church Place, where it stands to this day. It is believed to be the largest parish church in Ireland.[64]

Following passage of the Catholic Relief Act, Charles Brownlow granted a site to the Roman Catholic parish priest the Reverend William O'Brien in 1829 for the construction of a church on Distillery Hill, now known as lower North Street. It was there that work began in 1832 on what is now St Peter's Church.[65] In 1966, another Catholic church, St Paul's, was built at the junction of Francis Street and Parkview Street. This was a radical departure from traditional church architecture with its grey plaster finish, copper roof, slim spire, hexagonal angles and modern design throughout. Many of its architectural features such as the copper roof and gray plaster finish are shared by the neighbouring St Paul's School. It was designed to cope with the extra demand for worship space following the growth of the surrounding Taghnevan and Shankill housing estates.[66]

The Lurgan Museum houses one of the largest collections of items relating to Irish History in Northern Ireland. The Museum has many photographs and artefacts connected with Lurgan life over the past 150 years. It houses an extensive collection relating to the periods known as "The Troubles", "Operation Harvest" 1956-62, and "The 1916 Easter Rising". This collection also has a popular section covering the social history of the area.

The first Methodist church was built in Nettleton's Court, Queen Street in 1778. It was found to be too small and a new church was built on High Street in 1802, and replaced by a newer building in front of it in 1826. This was extensively renovated in 1910 and stands to this day sporting a simple facade.[67]

Education

It was the late 19th century that saw the development of formal education in Lurgan and a significant move away from the less organised hedge schools of before.[68]

Today, schools in Lurgan operate under the Dickson Plan, a transfer system in north Armagh that allows pupils at age 11 the option of taking the 11-plus exam to enter grammar schools, with pupils in comprehensive junior high schools being sorted into grammar and non-grammar streams. Pupils can get promoted to or demoted from the grammar stream during their time in those schools depending on the development of their academic performance, and at age 14 can take subject-based exams across the syllabus to qualify for entry into a dedicated grammar school to pursue GCSEs and A-levels.[69]

As is common in Northern Ireland, most of the schools in Lurgan are attended mainly by children from one or other of the two main ethno-religious blocs, reflecting the existence of deep-seated ethnic, sectarian and political divisions in society. Some schools are in the Catholic 'maintained' sector, i.e. maintained by the Council for Catholic Maintained Schools, and others are controlled directly by the state. Directly-controlled state schools generally have a predominantly Protestant intake.

Primary education

At primary level, schools attended by the Unionist/Protestant community are Carrick Primary School, Dickson Primary School, and King's Park Primary School.

The Model School was part of the national schools programme proposed in 1831 in which each county in Ireland would have at least one school that would serve as an example to other national schools in the area and as a teacher training establishment (although teacher training did not take place at this particular school). Initially it had a multi-denominational intake, offered such services as night classes and industry-relevant vocational courses, and was enthusiastically supported by William Brownlow who is thought to have brought the school to the town. It was undermined, however, by church interests, which were opposed to its lack of ecclesiastical control, and criticism of the efficiency of its management, hence losing much of its earlier prestige as the premier educational establishment in the town.[70] Over the years, the intake of Nationalist/Catholic students steadily increased, due mainly to being situated in the Catholic area of Lurgan. The student body is now almost 100% Catholic.

Other Catholic primary schools are Carrick Primary School, Bunscoil Naomh Proinsias, St. Francis' Primary School, St Teresa's Primary School, St Anthony's Primary School, Tannaghmore Primary School, and Tullygally Primary School.

Post-primary education

At secondary level, schools attended by the Unionist-Protestant community are Lurgan College, and Lurgan Junior High School (formerly part of Lurgan College of Further Education).

Lurgan College, now a co-ed 14–18 grammar school, was established in 1873 as an all-boys school to provide what was known as 'classical education' as opposed to the more practical vocational education on offer at the Model School. Its initial charter included a provision that "no person being in Holy Orders, or a minister of any religious denomination shall at any time interfere in the management of the said school, or be appointed to serve as master" and that no religious instruction was to take place during school hours.[68]

Secondary schools attended by the Nationalist-Catholic community were previously St Mary's Junior High School, St Paul's Junior High School, and St Michael's Grammar School, which have emerged to become one school spanning the 3 sites, St Ronan's College.

St Mary's Intermediate School was built on Kitchen Hill after land was acquired from the Sisters of Mercy in 1955 and was opened in 1959 as an all-girls school. The nearby all-boys St Paul's Intermediate School was opened in 1962, and both of these schools are now known as junior high schools.[66] Pupils attend these schools from age 11 to 13, at which time they have the option of transferring to St Michael's if they qualify. Those who do not qualify may stay on at St Paul's and St Mary's until minimum school leaving age at 16 and where the option of taking GCSE exams is available.

A significant number of people from Lurgan also attend the Catholic maintained Lismore Comprehensive School in Craigavon.

Lurgan Technical College was renamed Lurgan College of Further Education, and subsequently merged with Portadown CFE and Banbridge CFE into the larger Upper Bann Institute of Further and Higher Education (UBIFHE). Further education in the region was consolidated further when this institution was merged with other FE colleges in Armagh, Newry and Kilkeel to form the Southern Regional College. The Lurgan campus is one of the few educational institutions in the area with a mixed denominational intake. It offers vocational courses as an alternative to A-Levels, and adult education services.

Special needs education

Ceara School provides education for pupils aged 3 through 19 who have severe learning difficulties.[71]

Sport and leisure

Facilities

Lurgan has a municipal swimming pool and leisure complex called Waves. This includes a swimming pool, squash courts, a gym, and offers such activities as pilates, circuit training, and spinning classes.[72] Following a vote taken by Craigavon Borough Council on 7 April 2010, Waves is to be closed as will the Cascades Centre in Portadown, and both facilities are to be replaced by a large central swimming facility that will be built near the Craigavon balancing lakes.[73] Lurgan has two 18-hole golf courses,[74] an artificial ski slope[75] and an equestrian centre for show jumping.

Clubs

Lurgan has a large GAA presence in the area with Gaelic football being played by clubs Clan na Gael CLG (based at Páirc Mhic Daibhéid), Clann Éireann GAC (Páirc Chlann Éireann), Éire Óg CLG (Pine Bank, Craigavon), Sarsfields GAC (Páirc an tAth. Dhónaill Mhig Eoghain, Derrytrasna), St Mary's GAC (Aghagallon), St Michael's GAC (Magheralin), St Paul's GFC (Na Páirceanna Imeartha), St Peter's GAC (Páirc Naomh Peadar) and Wolfe Tone GAC, Derrymacash (Páirc na Ropairí)

The town is also home to the Association football clubs Glenavon F.C., Dollingstown F.C., Lurgan Celtic F.C., and Lurgan Town F.C.. There are another thirteen clubs that play in the Mid Ulster Football Leagues. They are Derryhirk United, Hill Street, Lurgan Institute, Taghnevan Harps, Silverwood United, Tullygally, Lurgan BBOB, Lurgan United, Goodyear, Craigavon City, Lurgan Thistle, Celtic Club (Lurgan No. 1), Oxford Sunnyside F.C.. Loughgrove and Sheffield Thursday F.C. play in the Lonsdale league. Glenavon is the most prominent of these, playing in the IFA Premiership.

Cricket has two clubs, Lurgan Cricket Club and Victoria Cricket Club. Rugby union is played by Lurgan RFC.

Tennis is played by Lurgan Tennis Club which is in Lurgan Park. Lurgan Golf Club is an 18-hole challenging parkland course bordering on Lurgan lake.

Railway links

Lurgan railway station opened by the Ulster Railway on 18 November 1841, connecting the town to Belfast Great Victoria Street in the east and Portadown and Armagh in the west. The Great Northern Railway of Ireland provided further access to the west of Ulster which was then closed in the 1950s and 1960s from Portadown railway station.

Presently Lurgan railway station is run by Northern Ireland Railways with direct trains to Belfast Great Victoria Street and as part of the Dublin-Belfast railway line. The Enterprise runs through Lurgan from Dublin Connolly to Belfast Central, and a change of train may be required at Portadown to travel to Newry or Dublin Connolly.[76]

Railway access at Sydenham links into George Best Belfast City Airport on the line to Bangor.

Road transport and public services

.jpg)

Lurgan is also situated by the M1 motorway connecting the town to Belfast. Bus services, provided by Translink, arrive and depart on a regular basis from bus stops on Market Street to Belfast, Portadown, Armagh, Dungannon, and surrounding areas.

Electricity is supplied by Northern Ireland Electricity which was privatised in 1993 and is now a subsidiary of ESB Group.[77] The gasworks used to be in North St., but there is no longer any town gas since it was abolished in Northern Ireland in the 1980s by the Thatcher government for being uneconomical,[78] although it was restored to the greater Belfast area in 1996. Water is supplied by Northern Ireland Water, a public owned utility.

Media

Lurgan is served by two weekly local newspapers. The Lurgan Mail, published by Johnston Publishing (NI),[79] reports news and sport from around the local area. The Lurgan and Portadown Examiner also reports local news and sport with an emphasis on photographs of local people at sporting and social events.

Notable people

Living people

- Jocelyn Bell Burnell, Northern Irish astrophysicist, discovered the first radio pulsars.

- Barry Douglas, classical pianist and conductor, has residences in Paris and Lurgan.

- Jim Harvey, Lurgan-born former professional footballer; former assistant manager of the Northern Ireland football team, has also played for Glenavon, Arsenal and Tranmere Rovers.

- Neil Lennon, manager of Hibernian, former manager of Glasgow Celtic and former captain of the Northern Ireland football team and Glasgow Celtic.

- Gayle Williamson, Miss Northern Ireland 2002; and Miss United Kingdom 2002

Deceased people

- Edward Costello, who took part in the Easter Rising in April 1916, received a fatal bullet wound to the head on 25 April and died in Jervis Street Hospital, Dublin.

- John Cushnie was a broadcaster and panellist on the BBC radio 4 show Gardeners' Question Time. He also presented the BBCNI TV show The Greenmount Garden.

- Field Marshal Sir John Greer Dill (25 December 1881 – 4 November 1944), a British commander in World War I and World War II and later a diplomat, was born in Lurgan in 1881.

- William Frederick McFadzean (9 October 1895 – 1 July 1916), died when he threw himself on a box of primed grenades prior to the Battle of the Somme and was awarded the Victoria Cross.[80]

- Len Ganley MBE, a former world championship snooker referee, was a resident of the town.

- Billy Hanna (c. 1929 – 27 July 1975) founder and first commander of the Ulster Volunteer Force's Mid-Ulster Brigade, was a native of Lurgan. He was shot dead outside his home in the Mourneview estate by members of his own organisation.[81]

- Sammy Jones (11 June 1911 – 1993), a former professional footballer who made over 100 appearances for Blackpool and received one cap for the Irish national team, was born in Lurgan in 1911.

- James Logan (20 October 1674 – 31 October 1751), was born in Lurgan. He became an American colonial statesman and scholar, secretary to his friend William Penn, and was noted as a jurist, political philosopher, and botanist.[82]

- Richard McGhee (1851 –7 April 1930) was an Irish Protestant Nationalist home rule politician. A Land League and trade union activist, he was a Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland for more than 20 years.

- Rosemary Nelson (4 September 1958 – 15 March 1999) was a human rights solicitor killed by a loyalist car bomb in 1999.[83]

- Martin O'Hagan, a journalist for The Sunday World newspaper, was murdered on 28 September 2001 in front of his wife near his own home in the town.[12]

- George William Russell (10 April 1867 – 17 July 1935), who wrote under the pseudonym Æ, was an Anglo-Irish supporter of the nationalist movement in Ireland. He was a critic, poet, painter, mystical writer, and was at the centre of a group of followers of theosophy in Dublin for many years.[84] He was born in William Street, Lurgan.

- Philip Felix Smith (5 October 1825 – 16 January 1906) was born in North Lurgan and was a recipient of the Victoria Cross. His birth is recorded in the parish of Shankill at St. Peter's RC Church.

- Norman Uprichard (20 April 1928 – 31 January 2011) was a goalkeeper who began his career playing Gaelic Football with St. Peter's GAC. His decision to sign for Glenavon cost him a league medal under the GAA's now-defunct 'Rule 27'. He was finally awarded his medal by St. Peter's in 2004. He went on to play for Swindon Town, Portsmouth and Southend United at club level, and won 18 caps for Northern Ireland at international level.[85]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lurgan. |

References

- ↑ Free Map Tools – "How Far Is It Between?"

- ↑ Placenames NI: Lurgan Archived 31 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Lutton, SC. "The Rise and Development of Portadown". Review – Journal of the Craigavon Historical Society Vol. 5 No. 2. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- 1 2 Weatherup, D.R.M. "The Site of Craigavon". Review – Journal of the Craigavon Historical Society Vol. 2 No. 1. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- 1 2 Clendinning, Kieran. "The Brownlow Family and the Rise of Lurgan". Review – Journal of the Craigavon Historical Society Vol. 1 No. 1. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ↑ "Lurgan History And Heritage". Archived from the original on 4 February 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2009.

- ↑ Kee, Robert (2000). The Green Flag: A History of Irish Nationalism. Penguin Group. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-14-029165-0.

- ↑ "The Irish Famine". Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- ↑ "The Lost City of Craigavon". Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- ↑ "The 'lost' city of Craigavon to be unearthed in BBC documentary". Portadown Times. 30 November 2007. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- 1 2 "UK: Northern Ireland Taskforce appeal after jobs blow". BBC. 18 September 1999. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- 1 2 Toolis, Kevin (30 September 2001). "A man who stood up for truth". London: The Observer. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- ↑ Coll, Bryan (4 April 2009). "Sectarian Tension Returns to Northern Ireland". Time. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- ↑ "Lurgan Park a sectarian battleground". Lurgan Mail. 25 October 2007. Retrieved 22 March 2010.

- ↑ "IRA blamed in blasts, seven injured". https://www.upi.com. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ "Placenames Database of Ireland". Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland Placenames Project". Archived from the original on 1 October 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ↑ "Townland Maps". Sinton Family Trees. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- ↑ "OSI Map Viewer". Ordnance Survey Ireland. Retrieved 25 February 2010. – Note: Select "historic" to view the townland boundaries

- ↑ "Weather Averages – Lurgan, GBR". msn.com. Microsoft. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- ↑ "Upper Bann". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 23 March 2010.

- ↑ "Lurgan – some quick facts". BBC. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ↑ Beckett, J C (1966). The Making of Modern Ireland 1603–1923. London: Faber & Faber. p. 406. ISBN 0-571-09267-5.

- ↑ Gailey, Andrew (May 1984). "Unionist Rhetoric and Irish Local Government Reform, 1895-9". Irish Historic Studies. 24 (93): 52–68. JSTOR 30008026.

- ↑ Shannon, Catherine B (March 1973). "The Ulster Liberal Unionists and Local Government Reform, 1885–98". Irish Historic Studies. 18 (71): 407–423. JSTOR 30005423.

- ↑ "Census for post 1821 figures". Archived from the original on 9 March 2005. Retrieved 23 August 2009.

- ↑ "Historical Populations". Retrieved 23 August 2009.

- ↑ "Lurgan, County Armagh". Belfast and Ulster Towns Directory for 1910. Retrieved 22 March 2010.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland Census of Population". Archived from the original on 17 February 2012.

- ↑ Lee, JJ (1981). "Pre-famine". In Goldstrom, J. M.; Clarkson, L. A. Irish Population, Economy, and Society: Essays in Honour of the Late K. H. Connell. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press.

- ↑ Mokyr, Joel; Ó Gráda, Cormac (November 1984). "New Developments in Irish Population History, 1700–1850". The Economic History Review. 37 (4): 473–488. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.1984.tb00344.x.

- ↑ "Census data". Northern Ireland Department of Health, Social Services, and Public Safety. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- ↑ "NISRA – Ward Information for Church ward 95LL07". Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- ↑ "NISRA – Ward Information for Court ward 95LL09". Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- ↑ "NISRA – Ward Information for Drumnamoe ward 95LL14". Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- ↑ "NISRA – Ward Information for Knocknashane ward 95LL18". Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- ↑ "NISRA – Ward Information for Mourneview ward 95LL20". Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- ↑ "NISRA – Ward Information for Parklake ward 95LL21". Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- ↑ "NISRA – Ward Information for Taghnevan ward 95LL22". Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- ↑ "NISRA – Ward Information for Woodville ward 95LL26". Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- ↑ Sandra J. Callaghan (2001). "Comparative Perspectives on Housing Segregation: Northern Ireland and US Frostbelt Cities". Retrieved 23 March 2010.

- 1 2 Jarman, Neil; Bryan, Bryan (1 May 1996). "Marching Through 1996" (PDF). Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- ↑ "Linen Industry – Lurgan". Craigavon Museum. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2010.

- ↑ "Textiles in Decline". BBC. 6 December 1999. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ↑ "Goodyear Closure". New York Times. 26 July 1983. Retrieved 22 March 2010.

- ↑ "Craigavon Area Plan 2010 Policy Framework: Industry". Northern Ireland Planning Service. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ↑ "John Lewis decision welcomed". Lurgan Forward. 26 May 2006. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- ↑ "Town meeting". Lurgan Mail. 25 March 2010. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Peter Richard (2002). Thesaurus of traditional English metaphors. Routledge. pp. F.28a.

- ↑ "The end of Master McGrath". Lurgan Mail. 11 March 2010. Retrieved 22 March 2010.

- ↑ "Lough Neagh Discovery Centre". Craigavon Borough Council. Archived from the original on 20 January 2010. Retrieved 24 February 2010.

- ↑ "Lurgan Park". Northern Ireland Tourist Board. Retrieved 4 March 2009.

- ↑ "Lurgan Park". Archived from the original on 24 March 2010. Retrieved 22 March 2010.

- ↑ "Lurgan Park". Disabled Ramblers Northern Ireland. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2010.

- ↑ "Ritchie opens play area at Mount Zion House, Lurgan". Northern Ireland Executive. 23 October 2008. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- ↑ "Lurgan War Memorial". Retrieved 23 March 2010.

- ↑ Weatherup, D.R.M. "Lurgan Free Library Before Carnegie". Review – Journal of the Craigavon Historical Society Vol. 6 No. 1. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ↑ McCorry, Francis X. "Residential Stability and Population Mobility in Lurgan, 1856–64". Review – Journal of the Craigavon Historical Society Vol. 5 No. 3. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ↑ "Town Halls". Craigavon Borough Council. Archived from the original on 25 March 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- ↑ "Brownlow House – History". Brownlow House. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- ↑ McCorry, Francis X. "Shankill Graveyard, Lurgan". Craigavon Historical Society. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- ↑ McCorry, Francis. "Parish of St. Peter's, Shankill". Dromore Diocesan Historical Society. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- ↑ "History from Headstones". BBC. Retrieved 22 March 2010.

- ↑ "About Us – Shankill Parish Church". Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- ↑ McCorry, Frank. "History of St Peter's Church". Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- 1 2 Clendinning, Kieran. "History of Saint Paul's Parish". Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- ↑ "J0858 : High Street Methodist Church, Lurgan". 2007. Retrieved 23 March 2010.

- 1 2 Wilson, Ian. "19th Century Schools in Lurgan – Part 2". Review – Journal of the Craigavon Historical Society Vol. 5 No. 1. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ↑ Emerson, Newton (30 August 2005). "Parents will have last word on Grammar schools". The Irish News via Slugger O'Toole. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- ↑ Wilson, Ian. "19th Century Schools in Lurgan". Review – Journal of the Craigavon Historical Society Vol. 4 No. 3. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ↑ "Secretary of State opens Ceara School, Lurgan". Southern Education and Library Board. 12 December 2001. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2010.

- ↑ "Waves Leisure Centre". swim.com. Archived from the original on 15 April 2010. Retrieved 24 February 2010.

- ↑ "Super-centre is on way as councillors vote for the closure of Cascades". Portadown Times. 9 April 2010. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- ↑ "World Golf". Retrieved 5 March 2009.

- ↑ "Craigavon Golf & Ski Centre". Northern Ireland Tourist Board. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- ↑ "Lurgan station" (PDF). Railscot – Irish Railways. Retrieved 28 August 2007.

- ↑ "NIE Energy – About Us". NIE Energy. Archived from the original on 17 January 2010. Retrieved 22 March 2010.

- ↑ "Gas (Northern Ireland) Order 1985". Hansard. 26 July 1985. Retrieved 23 March 2010.

- ↑ "The Lurgan Mail". British Newspapers Online. Retrieved 22 March 2010.

- ↑ "Your Place And Mine – Armagh". BBC. Retrieved 21 October 2008.

- ↑ CAIN: Sutton Index of Deaths: 1975

- ↑ "Encyclopedia of World Biography". 2004. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ↑ "So who did kill Rosemary Nelson?". The Guardian. London. 4 July 2009. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- ↑ "AE – George William Russell – Theospohical History". Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- ↑ Ponting, Ivan (12 February 2011). "Norman Uprichard: Goalkeeper who helped Northern Ireland reach the 1958 World Cup quarter-finals". The Independent. London. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

External links

Other links