Flushing–Main Street (IRT Flushing Line)

Flushing–Main Street | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

Center track | |||||||||

| Station statistics | |||||||||

| Address |

Main Street and Roosevelt Avenue Queens, NY 11354 | ||||||||

| Borough | Queens | ||||||||

| Locale | Flushing | ||||||||

| Coordinates | 40°45′34.28″N 73°49′49.14″W / 40.7595222°N 73.8303167°WCoordinates: 40°45′34.28″N 73°49′49.14″W / 40.7595222°N 73.8303167°W | ||||||||

| Division | A (IRT) | ||||||||

| Line | IRT Flushing Line | ||||||||

| Services |

7 | ||||||||

| Transit connections |

| ||||||||

| Structure | Underground | ||||||||

| Platforms | 2 island platforms | ||||||||

| Tracks | 3 | ||||||||

| Other information | |||||||||

| Opened | January 21, 1928[1] | ||||||||

| Station code | 447[2] | ||||||||

| Accessible |

| ||||||||

| Wireless service |

| ||||||||

| Traffic | |||||||||

| Passengers (2017) |

18,746,832[4] | ||||||||

| Rank | 10 out of 425 | ||||||||

| Station succession | |||||||||

| Next north |

(Terminal): 7 | ||||||||

| Next south |

Mets–Willets Point: 7 | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Next |

none: 7 | ||||||||

| Next |

Junction Boulevard: 7 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

|

Main Street Subway Station (Dual System IRT) | |||||||||

| MPS | New York City Subway System MPS | ||||||||

| NRHP reference # | 04001147[5] | ||||||||

| Added to NRHP | October 14, 2004 | ||||||||

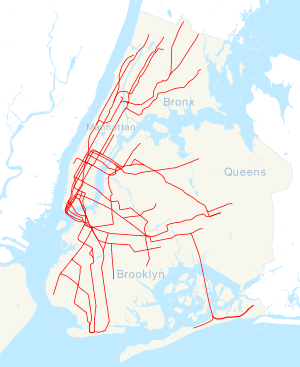

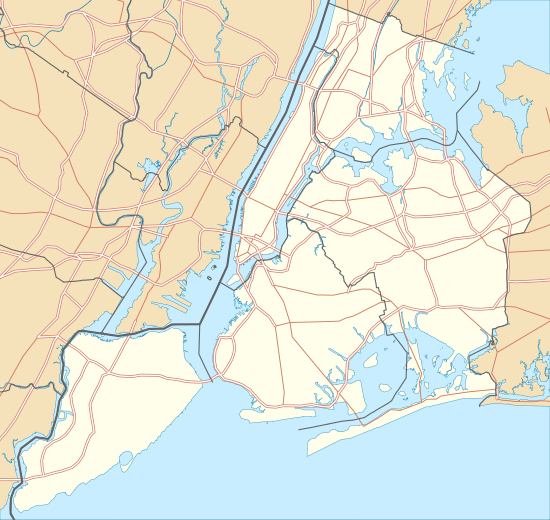

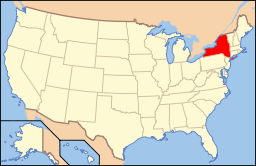

Flushing–Main Street (signed as Main Street on entrances and pillars, and Main St–Flushing on overhead signs) is the northern terminal station on the IRT Flushing Line of the New York City Subway, located at Main Street and Roosevelt Avenue in the Downtown section of Flushing, Queens.[6] It is served by the 7 at all times and the <7> train rush hours in the peak direction.[7]

The Flushing–Main Street station was originally built as part of the Dual Contracts between the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) and the Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation (BMT). It opened on January 21, 1928, completing the segment of the Flushing Line in Queens. Although plans existed for the line to be extended east of the station, such an extension was never built. The station was renovated in the 1990s. In 2017, it was the busiest single subway station in Queens and the 10th busiest subway station in the system.

History

The 1910 Dual Contracts called for extending IRT and BMT lines to Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx. Owing to Queens' lack of development at the time, it did not receive many new IRT and BMT lines compared to Brooklyn and the Bronx, since the New York Public Service Commission (PSC) wanted to alleviate subway crowding in the other two boroughs first before building in Queens. The IRT Flushing Line was to be one of two Dual Contracts lines in the borough, and it would connect Flushing and Long Island City, two of Queens' oldest settlements, to Manhattan via the Steinway Tunnel. When the majority of line was built in the early 1910s, most of the route went through undeveloped land, and Roosevelt Avenue had not been constructed.[8]:47 Community leaders advocated for more Dual Contracts lines to be built in Queens to allow development there.[9]

At the time of the line's planning, Downtown Flushing was a quiet Dutch-colonial-style village; what is now Roosevelt Avenue in the area was known as Amity Street, a major commercial thoroughfare in the neighborhood.[10][8]:49 In late 1912, Flushing community groups were petitioning the Public Service Commission (PSC) to depress the proposed line in Flushing into a subway tunnel, rather than an elevated line.[8]:51 Unlike a subway, an el would cause disturbances to the quality of life and a loss in nearby property values, as well as a widening of Amity Street that would cause more changes to the already existing town. One Amity Street property owner compared the planned effect of an elevated Flushing Line on Amity Street to the degradation of Myrtle Avenue in Brooklyn after the Myrtle Avenue Elevated was built there. On the other hand, a subway would only require that the street be widened, even though it was more expensive than an elevated of the same length.[8]:52–53

On January 20, 1913, because of these concerns, the Flushing Association voted to demand that any IRT station in Flushing be built underground.[8]:54 Due to advocacy for elevated extensions to the line past Flushing (see § Proposed extension of the line), the PSC vacillated on whether to build a subway or elevated for the next few months.[8]:56–60 The PSC finally voted to bring the Flushing portion of the line underground in April 1913. However, as the costs of a subway had increased by then, they decided to postpone discussion of the matter.[8]:60 In June 1913, the New York City Board of Estimate voted to allow the line to be extended from 103rd Street–Corona Plaza east to Flushing as a three-track line, with a possible two-track second phase to Bayside.[8]:61

The Flushing Line west of 103rd Street opened in 1917.[11] The IRT agreed to operate the line under the condition that any loss of profits would be repaid by the city.[12] As part of the agreement, the PSC would build the line eastward to at least Flushing.[12] The station, as well as two other stations at Willets Point Boulevard and 111th Street, was approved in 1921 as part of an extension of the Flushing Line past 103rd Street.[10] Construction of the station and the double-deck bridge over the Flushing Creek began on April 21, 1923, with the station built via cut-and-cover methods.[8]:71 The bridge was completed in 1927, and the station opened on January 21, 1928, over a decade after the line initially began operation.[1][8]:71[13]

Following the station's opening, Downtown Flushing evolved into a major commercial and transit center, as development sprung around the section of Main Street near the station.[8]:73–74 On April 24, 1939, express trains began operating to and from the station, in conjunction with the reconstruction of the Willets Point station for the 1939 World's Fair.[14][15] Due to the high level of passenger use, beginning in 1940 local residents requested an additional exit at the east end of the station, and the widening of existing staircases.[16][17][18][19] A new eastern entrance was added after World War II.[8]:72[20] Ground broke on the new entrance on November 5, 1947,[21][22] and it opened on October 28, 1948 with two new street stairs and an additional token booth.[23][22][24] Upon its initial opening, the new entrance did little to relieve crowding at the main fare control area.[23][22]

The platforms at Main Street and all other stations on the Flushing Line, with the exception of Queensboro Plaza, were extended in 1955–1956 to accommodate 565-foot-long (172 m), 11-car trains. The platforms at Queensboro Plaza could already fit 600-foot-long (180 m) BMT trains, so no extensions were built there.[25]

A station renovation had been planned since the 1970s. In 1981, the MTA listed the station among the 69 most deteriorated stations in the subway system.[26] The MTA finally found funding for the station's renovation in 1994—at the expense of the renovations of 15 other stations, including three Franklin Avenue Line stations and the Atlantic Avenue–Pacific Street, Roosevelt Avenue/74th Street, and 161st Street–Yankee Stadium station complexes—because the station was a "vital station" for commuters from Eastern Queens.[27] Between 1999 and 2000, the station underwent a major renovation project. The renovation added an elevator near the eastern Lippmann Plaza exit that made the station compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. The project also added new street entrances and a large entrance hall near Lippmann Plaza at the far east end of the station, beyond the bumper blocks at the end of the tracks.[13][28][29][30]

The Flushing–Main Street station has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places since October 2004. The National Park Service listed the station because it was considered a good historic example of Squire J. Vickers architecture during the time of construction.[31][5]

Proposed extension of the line

The station was not intended to be the Flushing Line's terminus.[8]:49[32] While the controversy over an elevated line in Flushing was ongoing in January 1913, the Whitestone Improvement Association pushed for an elevated to Whitestone, College Point, and Bayside. However, some members of that group wanted to oppose the Flushing line's construction if there was not going to be an extension to Whitestone. After the January 20 vote to demand that the subway line through Flushing be built underground, groups representing communities in south Flushing collaborated to push for an elevated along what was then the LIRR's Central Branch,[8]:53–55 in the current right-of-way of Kissena Corridor Park.[8]:277 Eleven days later, the PSC announced its intent to extend the line as an el from Corona to Flushing, with a possible further extension to Little Neck Bay in Bayside.[8]:56 There was consensus that the line should not abruptly end in Corona, but even with the 5.5-mile-long (8.9 km) extension to Bayside, the borough would still have fewer Dual Contracts route mileage than either Brooklyn or the Bronx. The New York Times wrote that compared to the Bronx, Queens would have far less subway mileage per capita even with the Flushing extension.[33]

The Bayside extension was tentatively approved in June 1913, but only after the construction of the initial extension to Flushing.[8]:61 Under the revised subway expansion plan put forth in December 1913, the Flushing Line would be extended past Main Street, along and/or parallel to the right-of-way of the nearby Port Washington Branch of the LIRR towards Bell Boulevard in Bayside. A spur line would branch off north along 149th Street towards College Point.[12]

In 1914, the PSC chairman and the commissioner committed to building the line toward Bayside. However, at the time, the LIRR and IRT were administered separately, and the IRT plan would require rebuilding a section of the Port Washington branch between the Broadway and Auburndale stations. The LIRR moved to block the IRT extension past Flushing since it would compete with the Port Washington Branch service in Bayside.[8]:62 One member of the United Civic Association submitted a proposal to the LIRR to let the IRT use the Port Washington Branch to serve Flushing and Bayside, using a connection between the two lines in Corona.[8]:63 The PSC supported the connection as an interim measure, and on March 11, 1915, it voted to let the Bayside connection be built. Subsequently, engineers surveying the planned intersection of the LIRR and IRT lines found that the IRT land would not actually overlap with any LIRR land.[8]:63[34] The LIRR president at the time, Ralph Peters, offered to lease the Port Washington and Whitestone Branches to the IRT for rapid transit use for $250,000 annually (equivalent to $6,050,000 in 2017), excluding other maintenance costs. The lease would last for ten years, with an option to extend the lease by ten more years. The PSC favored the idea of the IRT being a lessee along these lines, but did not know where to put the Corona connection.[8]:64 Even the majority of groups in eastern Queens supported the lease plan.[35] The only group who opposed the lease agreement was the Flushing Association, who preferred the original Flushing subway plan.[8]:64–65

Afterward, the PSC largely ignored the lease plan since it was still focused on building the first phase of the Dual Contracts. The Flushing Business Men's Association kept advocating for the Amity Street subway, causing a schism between them and the rest of the groups that supported the LIRR lease. Through the summer of 1915, the PSC and the LIRR negotiated the planned lease to $125,000 a first year, equivalent to $3,020,000 in 2017, with an eight percent increase each year; the negotiations then stalled in 1916.[8]:65–66 The Whitestone Improvement Association, impatient with the pace of negotiations, approved of the subway under Amity Street even though it would not serve them directly.[8]:66[36] The PSC's chief engineer wrote in a report that a combined 20,600 riders would use the Whitestone and Bayside lines each day in either direction, and that by 1927, there would be 34,000 riders per day per direction.[36][8]:67 The Third Ward Rapid Transit Association wrote a report showing how much they had petitioned for Flushing subway extensions to that point, compared to how little progress they had made in doing so.[37] Negotiations continued to be stalled in 1917.[8]:67 Despite the line not having been extended past Corona yet, the idea of a subway extension to Little Neck encouraged development there.[8]:68

The Whitestone Branch would have had to be rebuilt if it were leased to the subway, with railroad crossings removed and the single track doubled. The PSC located 14 places where crossings needed to be eliminated. However, by early 1917, there was barely enough money to build the subway to Flushing, let alone a link to Whitestone and Bayside.[8]:68 A lease agreement was announced on October 16, 1917,[38] but the IRT withdrew from the agreement a month later, citing that it was inappropriate to enter such an agreement at that time.[8]:68 Thereafter, the PSC instead turned its attention back to the Main Street subway extension.[8]:71

Even after the station opened in 1928, efforts to extend the line past Flushing persisted. In 1928, the New York City Board of Transportation (BOT) proposed allowing IRT trains to build a connection to use the Port Washington branch, but the IRT did not accept the offer since this would entail upgrading railroad crossings and the single-tracked line. Subsequently, the LIRR abandoned the branch in 1932.[8]:72 As part of the 1929 IND Second System plan, the Flushing Line would have had branches to College Point and Bayside east of Main Street.[8]:Chapter 3[39][40] That plan was revived in 1939.[41] The BOT kept proposing an extension of the Flushing Line past Main Street until 1945, when World War II ended and new budgets did not allow for a Flushing extension.[8]:72 In 1956, the Queens Chamber of Commerce and Queens Transit Committee again proposed the extensions east of the station to Bayside and College Point, along with a new spur along Kissena Boulevard running south to Sutphin Boulevard in Jamaica and eventually leading to John F. Kennedy International Airport.[42] Since then, several New York City Transit Authority proposals for an eastward extension have all failed.[8]:72

Station layout

| G | Street level | Entrances/exits to Main Street |

| M | Concourse | Lobby, station agent, MetroCard machines, escalator to Roosevelt Avenue |

| P Platform level |

Track 1 | ← |

| Island platform, doors will open on the left, right | ||

| Track M | ← | |

| Island platform, doors will open on the left, right | ||

| Track 2 | ← | |

Track layout | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The station has three tracks and two relatively narrow island platforms. It is located entirely under Roosevelt Avenue, which is 50 feet (15 m) wide (it had never been widened when the subway was built).[8]:73[28] When peak-direction express service operates, express trains leave from the middle and southernmost tracks, Track M and Track 2 respectively, while local trains leave from Track 1. This system was instituted in November 1952.[43] Mosaic on the wall tiles read "MAIN STREET", and small tiles along the platform walls read "M".[44]

At the west end of the platforms are the offices and dispatch tower for the IRT Flushing Line. Train crews report to the offices, while the dispatch tower dispatches trains and controls the Flushing Line. West of the station, the line rises from the tunnel via a portal at College Point Boulevard, and onto the elevated bridge across Flushing Creek.[8]:73

Main Street is one of only seven underground stations on the Flushing Line,[lower-alpha 1] one of three underground stations on the line in Queens,[lower-alpha 2] and the only underground station east of Hunters Point Avenue.[45]

Exits

There are nine entrances at street level, leading to two separate fare control areas.[28][6] The original street exit is in the middle of the platforms with a separate fare control mezzanine above the tracks, and the 24-hour station agent's booth.[17][19] Staircases lead up to all four corners of Main Street and Roosevelt Avenue.[28][6][17][19] The new fare control area at Lippmann Plaza has an extremely high ceiling, with the lobby itself located approximately 40 feet (12 m) below the street level. The mezzanine is at platform level, and provides an ADA-compliant elevator, three unidirectional escalators, and a stairway to street level at Lippmann Plaza.[13][28][6] New artwork titled Happy World was installed over the row of turnstiles in 1998.[13][28][46][47][48] The plaza, also known as Lippmann Arcade, is a pedestrian walkway that leads to a municipal parking lot and several bus stops on 39th Avenue.[28][6]

Bus service

In addition to connecting with the nearby Long Island Rail Road station of the same name, the station serves as one of the two busiest local bus-subway interchanges in Queens (along with Jamaica Center) and the largest in North America,[28][30][6] with over 20 bus routes running through or terminating in the area as of 2015.[49][50]

| Route | Operator | Stop location | North/West Terminal | South/East Terminal | via | notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local Bus Routes | ||||||

| NYCT | Roosevelt Avenue (near Lippmann Plaza) | Little Neck | Sanford Avenue, Northern Boulevard | |||

| 39th Avenue (near Lippmann Plaza) | Fort Totten | Northern Boulevard, Bell Boulevard | ||||

| Roosevelt Avenue (near Lippmann Plaza) | Beechhurst | 41st Avenue, 150th Street | ||||

| 39th Avenue (near Lippmann Plaza) | Fort Totten | Bayside Avenue | ||||

| Main Street | Jamaica–Merrick Boulevard | Kissena Boulevard, Horace Harding Expressway, 188th Street, Hillside Avenue | Northern terminal shifted from Main Street and 39th Avenue to 39th Avenue and 138th Street in August 2014. | |||

| MTA Bus | Roosevelt Avenue (west of Main Street) | Astoria | 30th Avenue, 58th Street, Woodside Avenue, 65th Place, 69th Street | |||

| NYCT | Main Street | College Point | Jamaica–Merrick Boulevard | Archer Avenue, Main Street, 20th Avenue (Q20A), 14th Avenue (Q20B) | ||

| MTA Bus | College Point | Jamaica–LIRR Station | Parsons Boulevard, Kissena Boulevard, 127th Street | |||

| NYCT | Roosevelt Avenue (near Lippmann Plaza) | Auburndale | Parsons Boulevard, 46th Avenue, Hollis Court Boulevard | Rush-hours only | ||

| Main Street | Queens Village or Cambria Heights | Kissena Boulevard, 46th Avenue, 48th Avenue, Springfield Boulevard | Northern terminal shifted from Main Street and 39th Avenue to 39th Avenue and 138th Street in August 2014. | |||

| 39th Avenue (near Lippmann Plaza) | Bay Terrace Shopping Center | Northern Boulevard, Crocheron Avenue, 32nd Avenue, Corporal Kennedy Street | ||||

| MTA Bus | Main Street | Whitestone | Jamaica–LIRR Station | Parsons Boulevard, Kissena Boulevard, Union Street | ||

| NYCT | Bronx Zoo–West Farms Square | Jamaica–Merrick Boulevard | Archer Avenue, Main Street, Union Street, Parsons Boulevard, Cross Bronx Expressway | Converted into Q44 Select Bus Service on November 29, 2015. | ||

| Roosevelt Avenue (west of Main Street) | LaGuardia Airport | Roosevelt Avenue, 108th Street, Ditmars Boulevard | ||||

| MTA Bus | Co-op City, Bronx | Whitestone Expressway, Hutchinson River Parkway, Bruckner Boulevard, Co-op City Boulevard | Limited-stop Service | |||

| NYCT | 41st Road | Ridgewood Terminal | Fresh Pond Road, Grand Avenue, Corona Avenue, College Point Boulevard | |||

| MTA Bus | Main Street | College Point | Jamaica–LIRR Station | 164th Street, 45th Avenue, College Point Boulevard | ||

| Roosevelt Avenue (west of Main Street) | Long Island City–Queens Plaza | 21st Street, 35th Avenue, Northern Boulevard | ||||

| NICE Bus | Roosevelt Avenue (near Lippmann Plaza) | Great Neck LIRR Station | Northern Boulevard | |||

Ridership

The passenger count in 2017 for the station was 18,746,832, making it the 10th busiest station system-wide, and the busiest station outside of Manhattan, as well as the busiest station served by one service.[4][28] This amounted to an average of 58,511 passengers per weekday.[51]

Attractions and points of interest

The station is located in Downtown Flushing, also known as Flushing Chinatown, one of New York City's largest Asian enclaves.[52][53]

Nearby points of interest include:

- Flushing Town Hall, at Northern Boulevard and Linden Place.[6]

- St George's Church, on Main Street near Roosevelt Avenue.[6]

- Flushing Main Post Office, on Main Street between Sanford and Maple Avenues.[6]

- Queens Library Flushing, at Main Street and Kissena Boulevard, the successor to the original Queens Library branch.[6][53]

- Lippmann Plaza, between 39th Avenue and Roosevelt Avenue east of Main Street. Named after longtime Flushing businessman Paul Lippmann.[6][54]

Gallery

- Eastern entrance, refurbished in 1999

Eastern entrance ticket hall

Eastern entrance ticket hall- A Q65 bus outside the station, at Main Street and Roosevelt Avenue

Notes

- ↑ The other six underground stations are 34th Street–Hudson Yards, Times Square, Fifth Avenue, Grand Central, Vernon Boulevard–Jackson Avenue, and Hunters Point Avenue.

- ↑ The other two underground stations in Queens are Vernon Boulevard–Jackson Avenue and Hunters Point Avenue.

References

- 1 2 "Flushing Rejoices as Subway Opens – Service by B.M.T. and I.R.T. Begins as Soon as Official Train Makes First Run – Hope of 25 Years Realized – Pageant of Transportation Led by Indian and His Pony Marks the Celebration – Hedley Talks of Fare Rise – Transit Modes Depicted" (PDF). The New York Times. January 22, 1928. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

- ↑ "Station Developers' Information". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ↑ "NYC Subway Wireless – Active Stations". Transit Wireless Wifi. Retrieved May 18, 2016.

- 1 2 "Facts and Figures: Annual Subway Ridership 2012–2017". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. July 12, 2018. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- 1 2 "NPS Focus". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Retrieved December 9, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "MTA Neighborhood Maps: Flushing" (PDF). mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. 2015. Retrieved July 5, 2015.

- ↑ "7 Subway Timetable, Effective June 24, 2018" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved June 24, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 Raskin, Joseph B. (November 1, 2013), The Routes Not Taken: A Trip Through New York City's Unbuilt Subway System, Fordham University Press, ISBN 978-0-8232-5369-2

- ↑ "Move for Rapid Transit" (PDF). Newtown Register. December 2, 1909. p. 1. Retrieved September 30, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- 1 2 "New Rapid Transit Commission Preparing Plans for Extension of Corona Line to Flushing – Board of Estimate Has Authorized Extension of Line From Corona to New Storage Yards Near Flushing River—Queensboro Subway to Have Connection With Proposed Eighth Avenue Line Near Times Square" (PDF). The New York Times. June 12, 1921. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

- ↑ "TRANSIT SERVICE ON CORONA EXTENSION OF DUAL SUBWAY SYSTEM OPENED TO THE PUBLIC; First Train From Grand Central Station Carries City Officials and Business Men Over New Route;-The Event Celebrated Throughout the Borough of Queens". The New York Times. 1917-04-22. Retrieved 2017-09-30.

- 1 2 3 "Flushing Line Risk Put on the City – Interborough Agrees to Equip and Operate Main St. Branch, but Won't Face a Loss – It May Be a Precedent – Company's Letter Thought to Outline Its Policy Toward Future Extensions of Existing Lines" (PDF). The New York Times. December 4, 1913. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Sheridan, Dick (April 12, 1999). "Moving Up on Main St. – Escalators Ready at Subway Station". Daily News (New York). Retrieved September 18, 2015.

- ↑ "Fast Subway Service to Fair Is Opened; Mayor Boards First Express at 6:25 A.M." The New York Times. April 25, 1939. p. 1. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

- ↑ "Mayor Starts First Express From Flushing". Long Island Star-Journal. April 24, 1939. p. 1. Retrieved July 16, 2016 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "'Early' Relief Is Late: Subway Exits Still Inadequate". Long Island Star-Journal. July 2, 1940. p. 4. Retrieved July 16, 2016 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- 1 2 3 "One-Way Commuters: It Might Solve The Jams". Long Island Star Journal. September 30, 1940. p. 6. Retrieved July 16, 2016 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "Flushing Subway Relief Proposed; Quinn Offers Plan for Two Extra Exits: Councilman Would Extend Existing Stairways to Ease Jam". Long Island Star-Journal. January 20, 1943. p. 1. Retrieved July 16, 2016 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- 1 2 3 "2 More Exits Promised For Flushing Subway". Long Island Star-Journal. March 27, 1946. p. 1. Retrieved July 16, 2016 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ Sullivan, Walter S. (December 21, 1947). "Longer Platforms Speeded For Ten-Car Trains on IRT" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Work Started on Two New Stairways To Ease Flushing Subway Station Jam". Long Island Star-Journal. November 6, 1947. p. 1. Retrieved September 1, 2016 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- 1 2 3 "New Stairs 'Snubbed' In Flushing Subway". Long Island Daily-Star. October 29, 1948. p. 2. Retrieved September 1, 2016 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- 1 2 "New Stairs 'Snubbed' In Flushing Subway". Long Island Daily-Star. October 29, 1948. p. 1. Retrieved September 1, 2016 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ Report for the three and one-half years ending June 30, 1949. New York City Board of Transportation. 1949.

- ↑ Authority, New York City Transit (1955). Minutes and Proceedings.

- ↑ Gargan, Edward A. (June 11, 1981). "Agency Lists Its 69 Most Deteriorated Subway Stations". The New York Times. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ↑ Jr, James C. Mckinley (November 15, 1994). "Subway Work In Flushing Is Restored". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 2, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Flushing Commons: Chapter 15: Transit and Pedestrians" (PDF). nyc.gov. June 9, 2010. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

- ↑ Onishi, Norimitsu (February 16, 1997). "On the No. 7 Subway Line in Queens, It's an Underground United Nations". The New York Times. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

- 1 2 Queens Courier Staff (June 10, 1999). "Main Street Station Nears Completion". The Queens Courier. Retrieved August 2, 2015.

- ↑ "New York (NY), Queens County". National Register of Historic Places. American Dreams, Inc.

- ↑ Wells, Pete (December 16, 2014). "In Queens, Kimchi Is Just the Start: Pete Wells Explores Korean Restaurants in Queens". The New York Times. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

We can blame the IRT. The No. 7 train was never meant to end at Main Street in Flushing.

- ↑ "Extension of Corona Line to Bayside Will Benefit Flushing Section of Queens" (PDF). The New York Times. 1913-02-09. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-09-30.

- ↑ "McCall and Maltbie Favor Transit Plan". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. March 6, 1915. p. 4. Retrieved 2017-09-30 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "9-FOOT PETITION FOR CARS.; Service Board Gets Plea of Several Long Island Towns" (PDF). The New York Times. 1915-04-02. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-09-30.

- 1 2 "Now Urge Action on Old Transit Plan". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. March 29, 1916. p. 14. Retrieved 2017-09-30 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Work for Transit is Called Wasted". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. May 18, 1916. p. 4. Retrieved 2017-09-30 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Agree on tentative Plan for Lease of Tracks in 3rd Ward". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. October 16, 1917. p. 14. Retrieved 2017-09-30 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Board of Transportation of the City of New York Engineering Department, Proposed Additional Rapid Transit Lines And Proposed Vehicular Tunnel, dated August 23, 1929

- ↑ Duffus, R.L. (September 22, 1929). "Our Great Subway Network Spreads Wider – New Plans of Board of Transportation Involve the Building of More Than One Hundred Miles of Additional Rapid Transit Routes for New York" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ↑ Project for Expanded Rapid Transit Facilities, New York City Transit System, dated July 5, 1939

- ↑ "Long Range 12-Point Transit Plan I To Serve Boro Needs For 50 Years". Queens Ledger. Fultonhistory.com. May 31, 1956. p. 8. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- ↑ "Flushing Train Departures Shifted To End Confusion at Main Street". Long Island Star-Journal. November 3, 1952. p. 17. Retrieved July 16, 2016 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ Cox, Jeremiah (August 14, 2008). Looking over to the opposite narrow platform with a name tablet (image) – via The Subway Nut.

- ↑ "Says City Delays Flushing Subway: Harkness Asks Estimate Board to Act on Contracts for Parts of Tube Extension" (PDF). The New York Times. March 1, 1923. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

- ↑ "Main Street Flushing Station". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Archived from the original on July 26, 2003. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ↑ "Artwork: Happy World (Ik-Joong Kang)". www.nycsubway.org.

- ↑ "MTA Arts & Design: Flushing-Main Street". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ↑ "Queens Bus Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. December 2017. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ↑ "Flushing To Jamaica Select Bus Service: January 22, 2015: Public Open House" (PDF). nyc.gov. Metropolitan Transportation Authority, New York City Department of Transportation. January 22, 2015. Retrieved July 6, 2015.

- ↑ "Facts and Figures: Average Weekday Subway Ridership 2012–2017". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. July 12, 2018. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- ↑ Wilson, Michael (October 25, 2008). "Familiar and Foreign, It's Main Street, New York City". The New York Times. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

- 1 2 Morrone, Francis (July 3, 2008). "Flushing, the New Face of the City". nysun.com. The New York Sun. Retrieved July 6, 2015.

- ↑ Rhoades, Liz (March 29, 2001). "Lippmann Plaza Upgrade Announced By City Planning". Queens Chronicle. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

Further reading

- Lee Stokey. Subway Ceramics : A History and Iconography. 1994. ISBN 978-0-9635486-1-0

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Flushing – Main Street (IRT Flushing Line). |

- nycsubway.org – IRT Flushing Line: Main Street/Flushing

- nycsubway.org – Happy World Artwork by Ik-Joong Kang (1998)

- Station Reporter – 7 Train

- The Subway Nut – Main Street–Flushing pictures

- MTA's Arts For Transit – Flushing–Main Street (IRT Flushing Line)

- Main Street entrance from Google Maps Street View

- Eastern entrance on Roosevelt Avenue from Google Maps Street View

- Platforms from Google Maps Street View

- Lobby from Google Maps Street View