Chinese numismatic charm

Yansheng Coin (simplified Chinese: 厌胜钱; traditional Chinese: 厭勝錢; pinyin: yàn shèng qián), in the west they are more commonly known as Chinese numismatic charms or simply Chinese charms (alternatively they may be known as Chinese amulets or Chinese talismans), refers to a collection of special kinds of coins and coin-shaped objects used mainly for ritual uses as well as fortune telling and are involved in almost all forms of Chinese superstitions and Feng shui. It was very popular in ancient China and even the Republic of China era. Normally these coins are privately funded or cast, such as by a rich family for their own family ceremony, though a few types have been known to be cast by various governments or religious orders over the centuries. They originated during the Han dynasty as a variant of the contemporary Ban Liang and Wu Zhu cash coins but evolved into their right right and into many different categories in various shapes and sizes over the centuries. Chinese numismatic charms typically contain a lot of hidden symbolism and visual puns. Unlike cash coins which usually only contain two or four Hanzi characters on one side Chinese numismatic charms often contain more characters and may or may not also contain pictures on the same side.

Chinese numismatic charms and amulets are not a real kind of currency, however as Chinese coins were valued by their weight in bronze or brass, Chinese numismatic charms tended to circulate on the Chinese market alongside regular government issued coinages as Chinese charms and amulets were often made from copper-alloys and in some cases from precious metals or jade,[1] and in certain cases some variants were sometimes used as alternative currencies especially temple coins issued by Buddhist temples during the Yuan dynasty when copper currency was scarce or its production was intentionally limited by the Mongol government. As some types of Chinese charms and amulets were used as daily fashion accessories many of them are worn.

The collection (e.g. antique collection, coin collection) of this kind of coins has a long history, and has been very popular since the Western Han Dynasty. Normally this kind of coins are heavily decorated, have complicated patterns, and even engraved.[2] Sometimes actual government cast Chinese cash coins can become Chinese numismatic charms such as the fact that in Feng shui Qing dynasty era cash coins with inscriptions of the five emperors Shunzhi, Kangxi, Yongzheng, Qianlong, and Jiaqing placed together are said to bring wealth and good fortune to those that string these five coins together.[3][4]

Chinese numismatic charms and amulets have inspired a similar tradition in Japan, Korea, and Vietnam and often charms and amulets from these other countries can be confused for Chinese charms due to their similar symbolism and inscriptions. Similarly Chinese cash coins themselves may be treated as "lucky charms" outside of China.

Names

Its formal name and pronunciation would be Yasheng coin/money (simplified Chinese: 压胜钱; traditional Chinese: 押胜钱; pinyin: yā shèng qián), but nowadays Yansheng is more widely known.

In Shuowen Jiezi, it records: "厌,笮也,今人作压。"[5] ("Yā(厌), bamboo ritual ware, nowadays (Western Han Dynasty period) people use as Yā (压)), which would imply the original meaning of Yasheng is for terrifying ghosts away and praying for victory.[6]

Sometimes, the nickname for the Yansheng coin also includes the so-called "flower coin" or "patterned coin" (simplified Chinese: 花钱; traditional Chinese: 花錢; pinyin: huā qián). They are alternatively referred to as "play coins" (wanqian, 玩钱) in China. Historically the term "Yansheng coin" was more popular but in modern China and Taiwan the term "flower coin" has become the more common name.[7]

History and usage

Yansheng coins were first appeared during the Western Han Dynasty. It was mainly originated from necromancy, for propitious wishes, terrifying ghosts, lucky money, or even for praying the victory of a war.

In the Ming and Qing Dynasties, the imperial government also issued such coins, such as for big festivals or ceremonies like the emperor's birthday or the introduction of a new inscription on government issued cash coins. For example, it was common for the emperor's sixtieth birthday to be celebrated by issuing a charm with the inscription Wanshuo Tongbao (萬夀通寶) because 60 years symbolises a complete cycle of the 10 heavenly stems and the 12 earthly branches.[8][9]

Origins

.jpg)

The earliest Chinese coinage bore inscriptions that described their place of origin during the Warring States period and sometimes their nominal value was included. Eventually other forms of notation such as circles possibly representing "the sun", crescents possibly representing "the moon", and dots possibly representing "the stars" as well as blobs and lines were inscribed on Ancient Chinese coinage. These symbols were sometimes protruded into the surface of the coin (Chinese: 阳文; Pinyin: yáng wén) and sometimes they were carved, engraved or incused (Chinese: 阴文; Pinyin: yīn wén) into these types of coins. These symbols would eventually evolve into Chinese charms with coins originally being used as charms.

Dots were the first and most common form of symbol (appearing mostly during the Han dynasty) that appeared on ancient Chinese cash coins such as the Ban Liang coins, these symbols though simple to produce usually appeared on the obverse side of the coins and were probably carved as a part of the mold, meaning that they were intentionally added. Crescent symbols are found on both the obverse and reverse sides of these coins and were also added around the same period as the dots, after this both regular Chinese numerals and counting rod numerals began to appear on ancient Chinese cash coins during the beginning of the Eastern Han dynasty. Chinese characters also began to appear on these early cash coins which could've meant that these coins should only circulate in certain regions or might've been the names of the people who cast these cash coins.

Coins made under Emperor Wang Mang of the Xin dynasty were later used as the basis of many Chinese amulets and charms because of how distinct these coins look from Han dynasty era coinage.[10][11]

Ancient Chinese texts refer to the Hanzi character for "star" (星) to not exclusively refer to the stars that are visible at night but to also have an additional meaning of "to spread" and "to disseminate" (布, bù), while other old Chinese sources claimed that the character for star was synonymous for the term for "to give out" and "to distribute" (散, sàn), based on these associations and the facts that coinage was seen as power that the dots that appeared on cash coins were thought to have the hidden meaning that cash coins should be akin to the star-filled night sky, and be widespread in circulation, numerous in quantity, and distributed throughout the world.

Another hypothesis on why star, moon, cloud and dragon symbols started appearing on Chinese cash coins is that they represent Yin and Yang and the Wu Xing, or more specifically the element of water (水), this hypothesis claims that the appearance of these symbols wasn't accidental but a manifestation of the fundamental belief of the ancient Chinese people of the time in Yin Yang energy and the elements of the Wu Xing. The Hanzi character for a "spring" (泉), which in this context refers to the underground source of water also meant "coin" in ancient China. In Chinese mythology the moon was an envoy or messenger from the heavens and water was cold air of Yin energy that was being accumulated and had their origins on the moon. As the moon was the spirit in charge of water in Chinese mythology and was in fact its essence the alleged meaning of crescent symbols representing "the moon" on cash coins could indicate that cash coins have to circulate just like water which flows, gushes, and rises. The symbolism of "clouds" or "auspicious clouds" in this context may then refer to the fact that clouds cause rain, in the Book of Changes the second trigram is mentioned to be representative of the element water which appear in the heavens as clouds, this would also imply that like flowing water cash coins should circulate freely. The appearance of wiggly-lines that represent Chinese dragons happened around this time as well and may have also been based on the Wu Xing element of water as dragons were thought to be water animals that were the bringers of both the winds and the rain, this would also confirm that dragons represented the nation that the circulation of cash coins should be free akin to how water flows. In later Chinese charms, amulets, and talismans the dragon became a symbol of the Chinese emperor as well as the central government of China and its power.[12][13][14][15]

Later developments

.jpg)

Most Chinese numismatic charms produced from the start of the Han dynasty until the end of the Northern and Southern dynasties were very similar in appearance to the Chinese cash coins that were in circulation, in fact the only differentiating factor that Chinese charms and amulets had at the time were the symbols on the reverse of these coins. These symbols included tortoises, snakes, double-edges swords, the sun, the moon, stars, depictions of famous people as well as the twelve Chinese zodiacs. The major development and evolution of Chinese numismatic charms and amulets happened during the period that started from the Six Dynasties and lasted until the Mongol Yuan dynasty. It was during this era that Chinese numismatic charms began using inscriptions that wished for "longevity" as well as "happiness", these charms and amulet became extremely common and widespread into Chinese society. Religious charms such as Taoist and Buddhist amulets also began to appear during this period as did marriage coin charms with "Kama Sutra-like" imagery. Chinese numismatic charms were not only made from copper-alloys anymore but also from iron, lead, tin, silver, and gold as well as porcelain, jade, and paper. New scripts and fonts also appeared on Chinese numismatic charms such as regular script, grass script, Seal script, and Taoist "magic writing" script.

Charms with inscriptions such as fú dé cháng shòu (福德長壽) and qiān qiū wàn suì (千秋萬歲)[16] were first cast around the end of the Northern dynasties period and then continued right through the Khitan Liao, Jurchen Jin and Mongol Yuan dynasties. During the Tang and Song dynasties open-work charms began to include images of Chinese dragons, Qilin, flowers as well as other plants, fish, deer, insects, Chinese phoenixes, fish, and human beings. The open-work charms from this era in Chinese history were usually used as accessories to clothes, adornment or to decorate horses. The very common Chinese numismatic charm inscription cháng mìng fù guì (長命富貴) was also introduced during the Tang and Song dynasties while the reverse side of these charms and amulets started showing Taoist imagery such as yin-yang symbols, the eight trigrams, and the Chinese zodiacs. It was also under the Song dynasty that a large number of Chinese charms and amulets were being cast, especially the number of Horse coins cast was large as horse coins were being used as gambling tokens and board game pieces. Under the reign of the Khitan Liao dynasty fish charms meant to be worn around the waist were introduced. Under the Jurchen Jin dynasty new types of Chinese numismatic charms and amulets emerged due to the influence of the steppe culture and arts of the Jurchen people. The Jin dynasty merged the Jurchen culture with the Chinese way of administration and the charms of the Jin dynasty innovated on the charms and amulets of the Song dynasty which used hidden symbolism, allusions, implied suggestions, and phonetic homonyms to describe a meaning. Under the Jurchens new symbolisms such as a dragon representing the Emperor and a phoenix the Empress emerged, tigers were used to represent the ministers, lions the government as a whole, and cranes and pine trees were used to describe longevity. Homonyms as hidden symbolism such as jujube fruits for "morning or early" and chickens symbolising "being lucky" also emerged under the Jurchens.

Under the Ming and Manchu Qing dynasties the manufacture of amulets with inscriptions that wish for good luck and those that celebrate events increased. These numismatic charms and amulets depict what is called the "three many", this name is used to describe happiness, longevity, and having many children and grandchildren. Other common wishes included those for wealth and receiving a high rank from the imperial examination system. During this period more Chinese numismatic charms and amulets started using implied and hidden meanings with visual puns, this practice was especially expanded upon under the Manchu Qing dynasty.[17][18][19][20]

Categories

Unlike government cast Chinese cash coins which typically only have four characters, Chinese numismatic charms often have more than four characters and depict images of various scenes.[21]

This kind of coins has several different styles:

- carved/engraved (Chinese: 镂空品; pinyin: lòukōng pǐn)

- with animal

- with people

- with plants

- words/characters on coin (Chinese: 钱文品; pinyin: qián wén pǐn)

- sentences/wishes (Chinese: 吉语品; pinyin: jí yǔ pǐn)

- Chinese zodiac/zodiac (Chinese: 生肖品; pinyin: shēngxiào pǐn)

- Taoism/Bagua (Chinese: 八卦品; pinyin: bāguà pǐn), or Buddhism gods (Chinese: 神仙佛道品; pinyin: shénxiān fú dào pǐn)

- Horses/military (Chinese: 打马格品; pinyin: dǎ mǎ gé pǐn)

- Abnormal or combined styles (Chinese: 异形品; pinyin: yìxíng pǐn)

Early Chinese numismatic charms tend to be cast while when the first struck coinage started appearing in China machine-struck amulets started to be made as well.

Types of Chinese charms

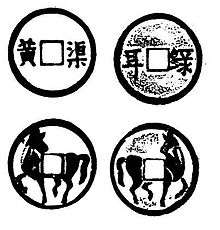

Horse coins

Horse coins (Traditional Chinese: 馬錢; Pinyin: mǎ qián) were a type of Chinese charm that originated in the Song dynasty, most horse coins tend to be round coins 3 centimeters in diameter with a circular or square hole in the middle of the coin. The horses featured on horse coins are depicted in various positions. it is currently unknown how horse coins were actually used though it is speculated that Chinese horse coins were actually used as game board pieces or gambling counters. Horse coins are most often manufactured from copper or bronze, but in a few documented cases they may also be made from animal horns or ivory. The horse coins produced during the Song dynasty are considered to be those of the best quality and craftsmanship and tend be made from better metal than the horse coins produced after.[22]

Horse coins often depicted famous horses from Chinese history, while commemorative horse coins would also feature riders, such as the horse coin that features “General Yue Yi of the State of Yan” commemorating the event that a Yan general attempted to conquer the city of Jimo.[23]

Zodiac charms

.jpg)

Chinese zodiac charms are types of charms based on either the twelve animals or the twelve earthly stems. These charms are based on the system of twelve ancient Chinese astronomers deduced by calculating the orbit of Jupiter, which was also applied to Earth, for this reason some ancient Chinese zodiac charms feature stellar constellations. By the time of the Spring and Autumn Period the twelve earthly branches which were associated with the months and the twelve animals became linked to each other which during the Han dynasty became linked to a person's year of birth.[24][25][26][27][28] Based on these traditions charms with inscriptions related to the twelve animals and twelve earthy branches, some ancient Chinese zodiac charms featured all twelve animals and others might also include the twelve earthly branches. It is not uncommon for zodiac charms to feature the character gua (挂) which indicates that the charm should be hung from a necklace or from the waist.[29] Modern Fengshui charms often incorporate the same zodiac based features.[30]

Numismatic charms for good luck

.jpg)

Chinese numismatic "good luck charms" or "auspicious charms" are special Chinese charms inscribed with various Chinese characters representing good luck and prosperity. As the idea that lucky charms had strong effects has traditionally been very popular in China they were also used to what some people think can scare away evil and presumably protect their families. Chinese "good luck charms" generally contain either 4 or 8 characters wishing for good luck, good fortune, money, a long life, many children, and good results in the imperial examination system.[31] Some Chinese "good luck charms" used images and/or visual puns to make a statement wishing for prosperity and success. Some Chinese "good luck charms" feature pomegranates which symbolise the desire to get successful and skilled male children as the ideal traditional Chinese family would contain 5 sons and 2 daughters as sons carry the ancestral lineage and take care of their family while daughters only take care of their in-laws.[32][33][34][35][36]

Some Chinese numismatic charms depict rhinoceroses which is considered a symbol associated with "happiness" due to the fact that the Chinese words for rhinoceros and "happiness" are both pronounced as xi, as the rhinoceros became extinct in Southern China during the ancient period they became mystified in Chinese legends causing the ancient Chinese to believe the stars in the sky were being reflected in the veins and patterns of a rhinoceros horn. The horn of the rhinoceros was believed that it could emit a vapour that could penetrate bodies water, traverse the skies and open channels to communicate directly with the spirits, for these reasons rhinoceroses are a common theme on Chinese numismatic charms.[37][38][39]

A number of good luck charms contain inscriptions such as téng jiāo qǐ fèng (騰蛟起鳳, “a dragon soaring and a phoenix dancing” which is a reference to a story of Wang Bo),[40] lián shēng guì zǐ (連生貴子, “May there be the birth of one honorable son after another”),[41] zhī lán yù shù (芝蘭玉樹, "A Talented and Noble Young Man"),[42]

Gourd charms

Gourd charms (Traditional Chinese: 葫蘆錢; Simplified Chinese: 葫芦钱; Pinyin: hú lu qián) are Chinese numismatic charms shaped like calabashes. The calabash in China is associated with medicine so these charms are used to wish for good health or for many sons as trailing calabash vines are associated with men and carry ten thousand seeds, for this reason gourd charms are considered an important symbol for people who wish to have large families. As the first character in gourd is pronounced as hú (葫) which sounds similar to the Chinese word for "protect" hù (護) or the word for "blessing" hù (祜) gourd charms are used to ward off evil spirits. As the number eight is considered to be an omen for good luck in China the fact that calabashes are shaped like the Arabic number "8" these charms are considered to be omens of good luck in the modern age. As calabashes were believed to have the magical power of protecting children from smallpox gourd charms are used with the belief that they keep children healthy as the belief is that the God of smallpox and the measles would transfer the smallpox from the child into the gourd charm. There exists a variant of the gourd charm which is shaped like two traditional cash coins stacked to resemble a calabash with a small cash-shaped coin on top and a bigger one at the bottom, these charms also just have 4 characters however they do not contain any inscriptions used on cash coins but contain auspicious messages.[43][44][45][46]

.jpg)

Some Chinese numismatic charms contain visual puns such as a Gourd charm that is composed of two replicas of Wu Zhu cash coins with a bat placed to obscure the characters that are nearest to each other, the Chinese word for bat sounds similar to that of "happiness", the square hole in the centre of a cash coin is referred to as an "eye" (眼, yǎn), and as the Chinese word for "coin" (錢, qián) has almost the same pronunciation as "before" (前, qián). For this reason this charm could be interpreted as "happiness is before your eyes".[47]

Eight Treasures charms

.jpg)

Chinese Eight Treasures charms (Traditional Chinese: 八寶錢; Simplified Chinese: 八宝钱; Pinyin: bā bǎo qián) depict the Eight Treasures, these treasures are also known as the "Eight Precious Things" and the "Eight Auspicious Treasures",[48][49][50] but in actuality refer to a large group of items from antiquity known as the "Hundred Antiques" (百古) which consists of objects utilised in the writing of Chinese calligraphy such as painting brushes, ink, writing paper and ink slabs as well as other antiques such as Chinese chess, paintings, Chinese music and various others. Most commonly cash coins, the ceremonial Ruyi, coral, lozenge, Rhinoceros horns, sycees, stone chimes, and the flaming pearls are depicted on older charms. "Eight Treasures charms" can display the eight precious organs of the Buddha's body, the eight auspicious signs, or the various emblems of the eight Immortals from Taoism as well as eight normal Chinese character. Variants without inscriptions also exist.[51][52]

Liu Haichan and the Three-Legged Toad charms

These are Chinese charms depict Liu Haichan and the Jin Chan, Liu Haichan is one of the most popular figures to appear on Chinese charms, the symbolism behind these charms can differ from region to region as in some varieties of Chinese, the character chan has a pronunciation very similar to qián (錢) which means "coin". Because the Jin Chan lives on the moon these charms symbolise wishing for that which is "unattainable" which can be interpreted as that these charms are the most auspicious and conducive to attracting good fortune to the holder. While contradictory the moral of these charms can be interpreted as that attaining money is the fatal attraction which can lure a person to their downfall.[53][54][55][56]

Vault Protector coins

Vault Protector coins (Traditional Chinese: 鎮庫錢; Simplified Chinese: 镇库钱; Pinyin: zhèn kù qián) were a type of coin created by Chinese mints that were a lot larger, heavier and thicker than regular cash coins and were well-made as they were designed to occupy a special place within the treasury of the mint. The treasury had a spirit hall for offerings to the gods of the Chinese pantheon, Vault Protector coins would oftentimes be hung with red silk and tassels for the Chinese God of Wealth and these coins were believed to have charm-like magical powers that would protect the vault from misfortune while bringing wealth and fortune to the treasury.[57][58]

The Book of Changes and Bagua charms (Eight Trigram charms)

Chinese charms depicting illustrations and subjects from the I-Ching are used to wish for the cosmic principles associated with divination in Ancient China such as simplicity, variability, and persistency. Bagua charms may also depict the Eight Trigrams. Bagua charms commonly feature depictions of trigrams, the Yin Yang symbol, Neolithic jade cong's (琮), the Ruyi sceptre, bats, and cash coins.[59][60][61][62][63][64][65]

Book of Changes and Bagua charms are alternatively known as Yinyang charms (Traditional Chinese: 陰陽錢) because of the fact that the Taijitu is often found with the eight trigrams.[66][67] This is also a popular theme for Vietnamese numismatic charms and many Vietnamese versions contain the same designs and inscriptions.[68]

Open-work charms

Open-work money (Traditional Chinese: 鏤空錢; Simplified Chinese: 镂空钱; Pinyin: lòu kōng qián) also known as "elegant" money (Traditional Chinese: 玲瓏錢; Simplified Chinese: 玲珑钱; Pinyin: líng lóng qián) are a collection of types of Chinese numismatic charms characterised by irregular shaped "openings" or "holes" between the rest of the design elements of these coins and they tend have a single large round hole in the middle of the coin, while open-work charms that feature designs of temples and other buildings tend to have a square hole in the centre similar to Chinese cash coins. The majority of open-work charms are exclusively decorated with images which are identical on both sides of the coin only reversed, while open-work charms that contain Chinese characters are rare. Compared to other Chinese charms open-work charms are notable for more often being made from bronze than brass and being significantly larger. The first Chinese open-work charms can be dated to the Han dynasty, though the majority of those from this era are small specimens taken from various utensils. They became more popular during the reigns of the Song, Mongol Yuan, and Ming dynasties but loss popularity under the Manchu Qing dynasty.[69][70][71][72][73][74]

Categories of open-work charms:

| Category | Image |

|---|---|

| Open-work charms with immortals and people |  |

| Dragon open-work charms |  |

| Phoenix open-work charms | |

| Peacock open-work charms |  |

| Chinese Unicorn open-work charms | |

| Bat open-work charms | |

| Lotus open-work charms | |

| Flower and Vine open-work charms | |

| Open-work charms with buildings and temples[lower-alpha 1] | |

| Fish open-work charms | .jpg) |

| Deer open-work charms |  |

| Lion open-work charms | |

| Tiger open-work charms | |

| Rabbit open-work charms | |

| Bird open-work charms | |

| Crane open-work charms | |

| Horse open-work charms |

24 character charms ("Good Fortune" and Longevity Charms)

.jpg)

24 character "Good Fortune" charms (Traditional Chinese: 二十四福字錢; Simplified Chinese: 二十四福字钱; Pinyin: èr shí sì fú zì qián) and 24 character longevity charms (Traditional Chinese: 二十四壽字錢; Simplified Chinese: 二十四寿字钱; Pinyin: èr shí sì shòu zì qián) refer to Chinese numismatic charms which have twenty-four characters on them and either contains a variation of the Hanzi character fú (福, good luck) or shòu (壽, longevity) which are the most common and second most Hanzi characters to appear on Chinese charms, respectively.[75][76][77][78][79] The Ancient Chinese believed that the more characters a charm had the more good fortune it would bring, although it is currently unknown why 24 characters is the default used for these charms. One proposition claims that 24 was selected because it is a multiple of the number 8 which was seen as auspicious to the Ancient Chinese due to how the number 8 is pronounced in several varieties of Chinese where the pronunciation is close to that of "good luck", another proposed possibility as to why 24 characters were selected for these charms is because of the twelve Chinese zodiacs and the twelve earthly branches of Chinese mythology. Other possibilities include that these Chinese charms are based on the fact that the Chinese feng shui special compass (罗盘) has 24 directions, that Chinese years are divided in 12 months and 12 shichen, the fact Chinese season markers are divided into 24 solar terms, or the 24 examples of filial piety from Confucianism.[80][81][82]

Old Chinese Chess (Xiangqi) pieces

The game of Xiangqi was originally played with either metallic or porcelain chess pieces during ancient times and these pieces were often collected and researched by those with an interest in Chinese cash coins,[83][84] Chinese charms and horse coins. These coins are regarded as a type of Chinese charm and are divided into the following categories:[85][86][87][88]

- Elephants (象)

- Soldiers (卒)

- Generals (将)

- Horses (马)

- chariots (車)

- guards (士)

- Canons (炮)

- Palaces (宫)

- Rivers (河)

The earliest discovered Xiangqi pieces date to the Chongning era (1102-1106) of the Song dynasty and were unearthed in the province of Jiangxi in 1984. These chess charms were also found along the Silk road in provinces like Xinjiang and were also used by the Tanguts of the Western Xia dynasty.[89][90][91]

Safe journey charms

Safe journey charms or safe passage charms are a major category of Chinese numismatic charms, these charms were produced out of a concern by people for their safety while traveling. One side would usually contain an inscription wishing for the holder of this charm to be granted a safe journey, while the other would contain aspects used on many Chinese charms and amulets such as the Bagua, weapons, and stars. It is also believed that the Boxers used safe journey charms as badges of membership during their rebellion against the Manchu Qing dynasty.[92]

Chinese Spade charms

.jpg)

Spade charms are Chinese charms based on Spade money, as Chinese charms first emerged during the Han dynasty most Chinese numismatic charms actually imitated the round coins with a square hole in the middle that circulated at the time, but as Chinese numismatic charms started to evolve separately from government minted Ancient Chinese coinage,[93] and coins shaped like spades, locks, fish, peaches, gourds, etc. emerged,[94][95][96][97] but most Chinese charms kept looking like contemporary Chinese coinage. Spade charms are based on Spade money which circulated during the Zhou dynasty until they were abolished by the Qin dynasty,[98][99] spade money was briefly reintroduced by Wang Mang during the Xin dynasty. Chinese spade charms are generally based on the spade money that was produced under the Xin dynasty by Wang Mang.[100][101][102]

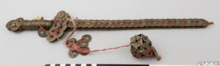

Chinese lock charms

.png)

Chinese lock charms (Traditional Chinese: 家鎖; Simplified Chinese: 家锁; Pinyin: jiā suǒ) are Chinese numismatic charms based on locks symbolising protection from evil spirits of both the holder and their property as well as (supposedly) bring good fortune, high results in the imperial examination system, and longevity and could often be found around the necks of children tied by either Buddhist and Taoist priests. Chinese lock charms actually do not have any moving parts and are flat, their form resembles that of the Hanzi character “凹” which can translate to "concave", all Chinese lock charms have Chinese characters on them. An example of a Chinese lock charm is the "hundred family lock" (Traditional Chinese: 百家鎖), this lock charm lends its name to the fact that the families of the babies would give areca nuts to other families who were vested in the personal security of the newborn to invite them to donate some of their cash coins to create this lock charm. Many Chinese lock charms are used to wish for stability. Other designs of lock charms include religious mountains, the Bagua, and Yin Yang symbol.[103][104][105][106][107][108]

Chinese star charms

Chinese star charms refers to Song dynasty era dà guān tōng bǎo (大觀通寶) cash coins that depict star constellations on the reverse side of the coin,dà guān tōng bǎo cash coins are often considered to be one of the most beautiful Chinese cash coins because of their “slender gold” script (瘦金書) which was written by Emperor Huizong himself. The reason why this coin was used to make star charms is because the word guān means star gazing and is a compound word for astronomy and astrology.[109]

"Five poisons" charms and amulets

_-_Scott_Semans.png)

"Five poisons" charms and amulets (五毒錢) are Chinese charms or Yansheng coins decorated with inscriptions and images related to the fifth day of the fifth month of the Chinese calendar (天中节) as this day indicated the start of the summer which was accompanied with dangerous animals and bugs as well as the spread of pathogens through infection and the alleged appearance of evil spirits, for this reason this day was marked to be the most inauspicious of all days on the Chinese calendar. An example of a Five poisons charm would bear the legend "五日午时" ("noon of the 5th day"). One of the most common ways many ancient Chinese people attempted to protect themselves on this day was by wearing "five poisons" charms around their necks and especially around the necks of their children. These charms display the "five poisons" (五毒) which are five animals namely snakes, scorpions, centipedes, toads, and spiders although sometimes lizards are included instead of spiders and the three-legged toad or tiger may sometimes be seen as one of the "five poisons", the purpose of these amulets is actually to counter the hazardous effects of the animals displayed on the amulet as the ancient Chinese believed that poison could only be thwarted with poison, e.g. mixing quicksilver with wine.[110][111][112][113][114]

Nine-Fold Seal Script charms

Nine-Fold Seal Script charms (Traditional Chinese: 九疊文錢; Simplified Chinese: 九叠文钱; Pinyin: jiǔ dié wén qián) are Chinese numismatic charms that are written in nine-fold seal script, a style of seal script that was in use from the Song dynasty until the Qing dynasty. Nine-Fold Seal Script charms cast during the Song dynasty are rare, around the end of the Ming dynasty there were Nine-Fold Seal Script charms cast with the obverse inscription fú shòu kāng níng (福壽康寧, “happiness, longevity, health and composure”), on the reverse side of this charm the text bǎi fú bǎi shòu (百福百壽, “one hundred happinesses and one hundred longevities”) was written.[115]

"Eight Decalitres of Talent" charms

The "Eight Decalitres of Talent" charm is a Qing dynasty era handmade charm that has a blue coloured rim, the left and right characters are painted green while the top and bottom characters are painted orange. This charm has the inscription bā dòu zhī cái (八鬥之才) which could be translated as “eight decalitres of talent”, this inscription is a reference to a story where Cao Zhi outed to his brother Cao Pi opposing the fact that he was being oppressed by his older brother out of envy for his talents. The inscription was devised by the Eastern Jin dynasty poet Xie Lingyun as a reference saying that talent was divided in ten pieces and that Cao Zhi alone contains eight of the ten.[116]

Fish charms

Fish charms (Traditional Chinese: 魚形飾仵; Simplified Chinese: 鱼形饰仵; Pinyin: yú xíng shì wǔ) are Chinese numismatic charms shaped like fish, as the Chinese character for fish "魚" (yú) is pronounced the same as that for surplus "余" (yú)[117][118][119][120] the symbol for fish has traditionally been associated with good luck, fortune, longevity, fertility, and many other auspicious things. As the Chinese character for profit "利" (lì) is pronounced similar to carp (鯉, lǐ),[121][122][123][124][125] carps are most commonly used for the motif of Chinese fish charms. As in ancient times the knowledge of medicine wasn't as advanced as today the mortality rate for Chinese children was high and their guardians would use fish charms to supposedly protect them and many fish charms would feature inscriptions wishing for the Chinese children who would carry them to stay safe and live.[126][127][128]

Chinese peach charms

Chinese peach charms (Traditional Chinese: 桃形掛牌; Simplified Chinese: 桃形挂牌; Pinyin: táo xíng guà pái) are peach-shaped Chinese numismatic charms used to wish for longevity, as longevity has traditionally due to Confucianism always been valued very highly to the point that Chinese Emperors would write the character for longevity (壽) to those of the lowest social class if they had reached high ages,[129][130] and in Chinese culture this was seen to be among the greatest gifts, for this reason this character often appears on peach charms and other Chinese numismatic charms. Chinese peach charms often depict the Queen Mother of the West or may depict inscriptions such as “長命” (cháng mìng meaning long life) written in seal script. Ancient Chinese Peach charms were also used to wish for wealth depicting the character “富” or higher Mandarin ranks using the character “貴”.[131][132][133]

Peace charms

_-_Scott_Semans.png)

Peace charms (Traditional Chinese: 天下太平錢; Simplified Chinese: 天下太平钱; Pinyin: tiān xià tài píng qián) are Chinese numismatic charms that depict inscriptions wishing for peace and prosperity and are based on Chinese coins that use the Chinese characters "太平" (tài píng)[134][135][136] and these coins are also often considered to have charm-like powers, these coins were originally thought to have been cast first by either the Eastern Han dynasty or the Jin dynasty at the order of Zhao Xin, who was the governour of Yizhou prefecture and placed the order after he captured the city of Chengdu, but today most sources establish that they were first cast by the Kingdom of Shu after the collapse of the Han dynasty after some archeological finds were made during the 1980s in Sichuan, the Shu Han era coin bore the inscription tài píng bǎi qián (太平百錢) and was worth one hundred Chinese cash coins, the calligraphic style of this coin resembles that of Chinese charms more than it did the contemporary currency. During the Song dynasty Emperor Taizong issued a coin with the inscription tài píng tōng bǎo (太平通寶), and later a Ming dynasty coin was with the inscription tài píng (太平) on the reverse of the coin and chóng zhēn tōng bǎo (崇禎通寶) on the obverse under the reign of the Chongzhen Emperor. During the Taiping Rebellion the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom issued coins (which were referred to as "holy coins") with the inscription tài píng tiān guó (太平天囯). Peace charms, which were unofficial privately cast coins that we were created due to the desire to wish for peace because of China's turbulent and often violent history, these charms were used on a daily basis throughout Chinese history. Under the Qing dynasty Chinese charms with the inscription tiān xià tài píng (天下太平) became a common sight, this phrase could be translated as "peace under heaven", "peace and tranquility under heaven", or "an empire at peace". Peace charms are also found to depict the twelve Chinese zodiacs and contain visual puns.[137][138][139][140]

During the Qing dynasty a tài píng tōng bǎo (太平通寶)[lower-alpha 2] peace charm was created that had additional characters and symbolism at the rim of the coin, on the left and right sides of the charm the characters 吉 and 祥 which can be translated as "good fortune", while on the reverse side the characters rú yì (如意, “as you wish”) are located at the top and bottom of the rim. When these four characters are combined they read rú yì jí xiáng which is translated as “good fortune according to your wishes”, this is a popular expression in China. This charm is notably very rare in its design due to the fact that it has what the Chinese refer to as a “double rim” (重輪), this feature is only rarely found in Chinese cash coins and charms and can be described as having a circular and thin rim surrounding the broad outer rim, further than that this specific charm also has an additional inscription in the recessed area of the rim, an example of a contemporary Chinese cash coin which had these features would be a 100 cash xianfeng zhongbao (咸豐重寶) coin. On the reverse side of this Manchu Qing dynasty era charm are a multitude of inscriptions that have auspicious meanings such as qū xié qiǎn shà (驅邪遣煞, “expel and strike dead evil influences”), tassels and swords which represent a symbolic victory of good over evil, two bats which is a visual pun as the Chinese word for bat is similar to the Chinese word for happiness and the additional inscription of dāng wàn (當卍, “Value Ten Thousand”) this is supposedly the symbolic denomination of this numismatic charm or “coin”.[141][142]

Tiger Hour charms

Tiger Hour charms are Chinese numismatic charms modelled after the Northern Zhou dynasty wǔ xíng dà bù (五行大布, “Large Coin of the Five Elements”) cash coins,[lower-alpha 3] but rather than having a square hole tiger hour charms tend to have a round one. Additionally on the reverse of these coins they feature the inscription yín shí (寅時) which is a reference to the Shichen of the tiger or the "tiger hour" and they feature an image of a tiger and a "lucky" cloud.[143]

Chinese burial coins

Chinese burial coins (Traditional Chinese: 瘞錢; Simplified Chinese: 瘗钱; Pinyin: yì qián) or dark coins (Traditional Chinese: 冥錢; Simplified Chinese: 冥钱; Pinyin: míng qián)[144][145] are Chinese imitations of currency that are placed in the grave of a person that is to be buried. The practice dates back to the Shang dynasty when cowrie shells were used, superstitions around this practice imply that the money would be used in the afterlife and be used as a bribe to Yan Wang who would then give a more favourable destination regarding for the spirit of the deceased. As the practice of burying money with the dead attracted grave robbers the practice changed to replace real money with replica currency as any representation of money could be used in the afterlife,[146][147] these coins and other imitation currencies were referred to as clay money (泥錢) or earthenware money (陶土幣). Clay versions of what the Chinese refer to as "low currency" (下幣) shch as cowrie shells, Ban Liang, Wu Zhu, Daquan Wuzhu, Tang dynasty Kaiyuan Tongbao, Song dynasty Chong Ni Zhong Bao, Liao dynasty Tian Chao Wan Shun, Bao Ning Tong Bao, Da Kang Tong Bao, Jurchen Jin dynasty Da Ding Tong Bao, and Qing dynasty Qian Long Tong Bao cash coins have been found in Chinese graves. Imitations of gold and silver "high currency" (上幣) are also known to appear in some Chinese graves, Clay versions of the Kingdom of Chu's gold plate money (泥「郢稱」(楚國黃金貨)), yuan jin (爰金), Silk funerary money (絲織品做的冥幣), gold pie money (陶質”金餅”), and other cake-shaped objects (冥器) have all been found in Chinese graves from various periods. Today clay imitations of currency are no longer used but has been replaced by Joss paper, which is burned rather than buried with the deceased subjects.[148][149][150][151]

Chinese "Laid to Rest" burial charms

Chinese "Laid to Rest" burial charms are bronze Chinese funerary charms or coins usually found in graves, they measure from 2.4 to 2.45 centimeters in diameter and have a thickness of 1.3 to 1.4 millimeters, they contain the obverse inscription rù tǔ wéi ān (入土为安) which means “to be laid to rest”, while the reverses of these coins are blank. These coins were mostly found in graves dating from the late Qing dynasty period but one of these coins was found in a coin hoard of Northern Song dynasty coins. the wéi is written using a simplified Chinese character (为) rather than the traditional Chinese version of the character (為). Due to many taboos these coins are excluded from numismatic reference books on either Chinese coinage or charms and amulets, in fact on many online coin forums it is not uncommon for Chinese commenters to state that they find these coins as either "horrifying" or "scary" due to the fact that they were put into the mouths of dead people and that these coins ought to be "thrown away because they are unlucky", for these reason these funerary charms tend to be extremely unwanted among collectors which explains their exclusion from reference books.[152][153][154][155]

Little shoe charms

Little shoe charms are Chinese charms based on the fact that shoes were associated with fertility and that the Chinese feminine ideal of small feet, which in Confucianism is associated with giving females a more narrow vagina, something the ancient Chinese saw as a sexually desirable trait and enable her to give birth to more male offspring, this was usually accomplished by binding a girl's feet from a young age. Little girls would hang these little shoe charms over their beds in the hope that they will help them find love. Chinese little shoe charms tend to be around an inch long. Shoes are also associated with wealth because their shape is similar to that of a sycee.[156]

Chinese football charms

During the Song dynasty there were Chinese numismatic charms cast that depict people playing the sport football, these charms display four images of football players in varying positions around the square hole in the middle of the coin, the reverse side of the coin depicts a dragon and a phoenix which are the traditional symbols representing men and women possibly indicating the unisex nature of the sport.[157][158]

Chinese cash coins with charm features

Some Chinese cash coins were known to display features commonly seen in Chinese numismatic charms, Chinese coins with charm features have been created over two thousand years ago with the early Ban Liang and Wu Zhu cash coins, and when the first Chinese charms started appearing during the Han dynasty these coins were already commonplace. Many government issued cash coins and other currencies such as Spade and Knife money that did not have any extra charm-like features were considered to also have “charm-like qualities” and were treated as charms by some people.[159][160][161] The Wang Mang era Knife coin with a nominal value of 5,000 cash coins was often seen as a charm by the people because the character 千 (or 1000) is written very similar to the character 子 which means "son" so the inscription of the Knife coin could be read as "worth five sons" as this was very much desired in ancient Chinese society. A coin from Shu Han with the nominal value of 100 Wu Zhu cash coins featured a fish on the reverse of the inscription which symbolises "abundance" and "perseverance" in Chinese culture. Another Shu Han era coin contained the inscription of Tai Ping Bai Qian which was taken as an omen of peace and this coin is often considered to be a peace charm. During the Jin dynasty a coin was issued with the inscription fēng huò (豐貨) which could be translated as "(the) coin of abundance" and it was believed by the people at the time that if someone would possess this coin that this would be economically beneficial for them which is why this coin is commonly referred to as the "cash of riches" in popular tongue.[162][163] During the Tang dynasty period images of clouds, crescents, and stars were often added on coins which the Chinese continued to use in subsequent dynasties. During the Jurchen Jin dynasty coins were cast with reverse inscriptions that featured characters from the twelve earthly branches and ten heavenly stems. During the Ming dynasty stars were sometimes used decoratively on some official government produced cash coins. Under the Manchu Qing dynasty yōng zhèng tōng bǎo (雍正通寶) cash coins cast by the Lanzhou Mint were considered to be charms or amulets capable of warding off evil spirits and demons because the Manchu word "gung" looked similar to the broadsword used by the Chinese God of War, Emperor Guan.[164][165] The commemorative kāng xī tōng bǎo (康熙通寶) cast for the Kangxi Emperor's 60th birthday in the year 1713 was believed to have "the powers of a charm" immediately when it entered circulation, this commemorative coin vontains a slightly different version of the Hanzi symbol "熙", at the bottom of the cash, as this character would most commonly have a vertical line at the left part of it but did not have it, and the part of this symbol which was usually inscribed as "臣" has the middle part written as a "口" instead. Notably, the upper left area of the symbol "通" only contains a single dot as opposed of the usual two dots used during this era. Several myths were attributed to this coin over the following three-hundred years since it has been cast such as the myth that the coin was cast from molten down golden statues of the 18 disciples of the Buddha which earned this coin the nicknames "the Lohan coin" and "Arhat money". These commemorative kāng xī tōng bǎo cash coins were given to children as yā suì qián (壓歲錢) during Chinese new year, some women wore them akin to how an engagement ring is worn today, and in rural Shanxi young men wore this special kāng xī tōng bǎo cash coin between their teeth like men from cities had golden teeth. Despite the myths surrounding this coin I was made from a copper-alloy and did not contain any gold but it was not uncommon for people to enhance the coin with gold leaf.[166][167][168]

Chinese marriage and sex education charms

Chinese marriage charms (Traditional Chinese: 夫婦和合花錢; Simplified Chinese: 夫妇和合花钱; Pinyin: fū fù hé hé huā qián), also known as "secret play" coins (Traditional Chinese: 秘戲錢; Simplified Chinese: 秘戏钱; Pinyin: mì xì qián), "secret fun" coins, "hide (evade) the fire (of lust) coins" (Traditional Chinese: 避火錢; Simplified Chinese: 避火钱; Pinyin: bì huǒ qián), Chinese marriage coins, Chinese love coins, Chinese spring money (Traditional Chinese: 春錢; Simplified Chinese: 春钱; Pinyin: chūn qián), Chinese erotic coins, Chinese wedding coins and many other names, are Chinese numismatic charms or amulets that depict scenes of sexual intercourse in various positions to illustrate how the newlywed couple should perform on their wedding night to meet their responsibilities and obligations to their family and Chinese society to produce children, dates and peanuts symbolising the wish for reproduction, lotus seeds symbolising "continuous births", chestnuts symbolising male offspring, pomegranates symbolising fertility, brans symbolising sons that will be successful, "dragon and phoenix" candles, cypress leaves, Qilins, bronze mirrors, shoes, saddles, and other things associated with traditional Chinese weddings.

The name "spring money" is a reference to an ancient Chinese ritual in which girls and boys would sing romantic music to each other from across a stream that is still practised by various minorities today. Sex acts were traditionally only scarcely depicted in Chinese art but stone carvings from the Han dynasty showcasing sexual intercourse were found and bronze mirrors with various sexual themes were common during the Tang dynasty. It was also during the Tang dynasty that coins graphically depicting sex started being produced. Chinese love charms often have the inscription "wind, flowers, snow and moon" (風花雪月) which is an obscure verse referring to a happy and frivolous setting, although every individual character might also be used to identify a Chinese goddess or the "Seven Fairy Maidens" (七仙女). Other Chinese wedding charms often have inscriptions like fēng huā yí rén (風花宜人), míng huáng yù yǐng (明皇禦影), and lóng fèng chéng yàng (龍鳳呈樣).[169][170][171][172][173][174] These charms could also be used in brothels where a man who would purchase the services of a prostitute but couldn't communicate in the local language would be able to simply point at the coin and communicate his desired sexual position to the prostitute.[175][176]

Some Chinese marriage charms contain references to the famous 9th century poem Chang hen ge, where characters are illustrated in four different sex positions and four Chinese characters representing the spring, wind, peaches, and plums.[177]

Chinese pendant charms

Chinese pendant charms (Traditional Chinese: 掛牌; Simplified Chinese: 挂牌; Pinyin: guà pái) are Chinese numismatic charms that are used as decorative pendants. Around the beginning of the Han dynasty a large number of Chinese charms appeared to be produced and the Chinese people started to wear some types of Chinese numismatic charms around their necks or waists as pendants or attached these charms to the rafters of their houses, pagodas, temples and many other buildings as well as on lanterns.[178][179][180][181] It is believed that open-work charms may have been the first Chinese charms that were used in this fashion. As time progressed many different types of Chinese charms were created and while some were worn on a daily basis others were exclusively used for specific rituals or holidays. Fish, lock, spade, and peach charms were all used to be worn on a daily basis and excluding the latter two were mostly worn by young children and infants. Some Han dynasty era charms contained inscriptions such as ri ru qian jin (日入千金, "may you earn a 1,000 gold everyday"), chu xiong qu yang (除凶去央, "do away with evil and dispel calamity"), bi bing mo dang (辟兵莫當, "avoid hostilities and ward off sickness"), or chang wu xiang wang (長毋相忘, "do not forget your friends"), while others mostly resembled contemporary cash coins with added dots and stars. Some pendant charms only contained a single loop while most others also had either a square or round hole in the centre. Some Chinese pendant charms contain the Hanzi character gua (挂) which translates as "to hang" in English, it is currently unknown why this extra character is added as these charms are always shapes like traditional pendants as the loops make them obvious to be hung somewhere or on someone. Although most pendant charms contain pictorial illustrations, the association of Chinese characters into new and mystical symbolic forms reached an even greater extreme when Taoists introduced "Taoist magic writing" (符文) where many Hanzi characters that were prominently featured on both Chinese cash coins and charms would become hidden symbolism.[182][183]

Chinese "World of Brightness" coins

During the late Qing dynasty the traditional cast coinage was slowly being replaced by machine-struck coinage, one of the first provincial mints to adopt machines for striking milled coinage was the Guangzhou Mint of the province of Guangdong, somewhere around this time machine-struck charms with the inscription guāng míng shì jiè (光明世界, "World of Brightness") started appearing that looked very similar to the contemporary milled guāng xù tōng bǎo (光緒通寶) cash coins. Currently numismatists haven't figured out either the meaning, purpose, or origin of these Chinese "World of Brightness" coins. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain both the meaning and usage of these coins, one hypotheses proposes that these coins were a form of hell money because it is thought that "World of Brightness" in this context would be a euphemism for "world of darkness" which is how the Chinese call death, another hypotheses suggests that these coins were gambling tokens, while another hypothesis has claimed that these coins used by the Heaven and Earth Society due to the fact that the Hanzi character míng (明) is a component of the name of the Ming dynasty (明朝), which meant that the inscription guāng míng (光明) could be read as "the glory of the Ming". There are 3 variations of the "World of Brightness" coin, the most common one contains the same Manchu characters on the reverse as the contemporary guāng xù tōng bǎo (光緒通寶) cash coins indicating that this coin was produced by the mint of Guangzhou, another version has the same inscription written on the reverse side of the coin, while a third variant has nine stars on the reverse aide of the coin.[184]

Chinese palindrome charms

Chinese palindrome charms are very rare Chinese numismatic charms that contain palindromes and depict what in China is known as "palindromic poetry" (回文詩), in this form of poetry the sentenced produced aren't always palindromes but simply have to make sense when reading in either direction.[185][186] Because of their rarity Chinese palindrome charms are usually excluded from reference books on Chinese numismatic charms. A known example of a presumably Qing dynasty period Chinese palindrome charm reads "我笑他說我看他打我容他罵" ("I, laugh, he/she, talks, I, look, he/she, hits, I, am being tolerant, he/she, scolds") in this case the meaning of the words can be altered depending on how this inscription is read, as definitions may vary depending on the preceding pronoun. Due to the nature of this charm it could be read both clockwise and counter-clockwise which could change the entire meaning of a sentence if read. Due to the way this inscription was written it tells of two sides of a combative relationship and could be read as representing either party.

| Traditional Chinese | Pinyin | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| 笑他說我 | xiào tā shuō wǒ | Laugh at him/her scolding me. |

| 看他打我 | kàn tā dǎ wǒ | Look at him/her fight me. |

| 容他罵我 | róng tā mà wǒ | Be tolerant of him/her cursing me. |

| 我罵他容 | wǒ mà tā róng | I curse and he/she is tolerant. |

| 我打他看 | wǒ dǎ tā kàn | I fight and he/she watches. |

| 我說他笑 | wǒ shuō tā xiào | I speak and he/she laughs. |

The reverse side of this coin features images of thunder and clouds.[187]

"Cassia and Orchid" charms

"Cassia and Orchid" charms are extremely rare Chinese numismatic charms dating to the Manchu Qing dynasty with the inscription guì zi lán sūn (桂子蘭孫, "cassia seeds and orchid grandsons"), these charms use the Mandarin Chinese word for Cinnamomum cassia (桂, guì) as a pun as it sounds similar to the Mandarin Chinese word for "honourable" (貴, guì) while the word for seed is also a homonym for son. The Mandarin Chinese word for orchid (蘭, lán) in this context refers to zhī lán (芝蘭 , "of noble character") which in this context means "noble grandsons". The inscription on the reverse side of this charm reads róng huá fù guì (榮華富貴, "high position and great wealth") describing a traditional Chinese family's wish to produce sons and grandsons who would pass the imperial examination and attain a great rank as a mandarin.[188][189]

Confucian charms

Confucian charms are Chinese numismatic charms that depict the traditions, rituals, and moral code of Confucianism such as filial piety and "righteousness".[190][191][192][193] Examples of Confucian charms would include a charm that depicts Shenzi carrying firewood on a shoulder pole, open-work charms depicting stories from "The Twenty-Four Examples of Filial Piety" (二十四孝),[194][195][196] the "five relationships" (五倫), Meng Zong kneeling besides bamboo, Dong Yong (a Han dynasty era man) working a hoe to earn money for his sick father after the death of his mother, Wang Xiang with a fishingpole, as well as coins with inscriptions such as fù cí zǐ xiào (父慈子孝, "the father is kind and the son is filial") read clockwise, yí chū fèi fǔ (義出肺腑, "righteousness comes from the bottom of one's heart"), zhōng jūn xiào qīn (忠君孝親, "be loyal to the sovereign and honor one's parents"), huā è shuāng huī (花萼雙輝, "petals and sepals both shine"), and jìng xiōng ài dì (敬兄愛第, "revere older brothers and love younger brothers").[197][198][199][200]

Men Plow, Women Weave charms

Men Plow, Women Weave charms (Traditional Chinese: 男耕女織錢; Simplified Chinese: 男耕女织钱; Pinyin: nán gēng nǚ zhī qián) are Chinese numismatic charms depicting scenes related to the production of rice and sericulture. Men Plow, Women Weave charms can feature inscriptions such as tián cán wàn bèi (田蠶萬倍, "may your (rice) fields and silkworms increase 10,000 times") on their obverse and may have images of a spotted deer on their reverse.[201][202][203]

Chinese money trees

Chinese money trees (Traditional Chinese: 搖錢樹; Simplified Chinese: 摇钱树; Pinyin: yáo qián shù) are Chinese numismatic charms shaped like trees with their leaves made out of replicas of cash coins, these money trees should not be with coin trees which are a by-product of the manufacture of cash coins, but due to their similarities it is thought by some experts they may have been related. Various legends from China dating to as early as the Three Kingdoms period mention a tree that if shaken would cause coins to fall off of its branches, and money trees as a charm have been found in Southwest Chinese tombs from the Han dynasty and later, where they are believed to have been placed there to help guide the dead to the afterlife and provide them with monetary support. According to one myth the origin of the money tree was that an old gray-haired man gave a farmer a special seed and then commanded the farmer to water the seed every day with his own sweat until the seed would sprout and then water it with his blood and after the tree had grown the farmer found out that if he would shake the tree that cash coins would fall out and that this effect was indefinite as the cash coins would grow back after every time which caused the farmer to become rich and the money tree would become an eternal source of wealth, this story was originally thought up to support the moral that one can only become wealthy through their own toil with their own sweat and blood. Literary sources claim that the actual origin of the money tree lies in the fact that the Chinese word for "copper" (銅, tóng) is pronounced similar to the word for "the Paulownia tree" (桐, tóng). The leaves of the Paulownia cash coins and become yellow during the Autumn causing them to physically look like either gold or bronze cash coins. Chen Shou (陳壽) mentions in the "Records of the Three Kingdoms" that a man named Bing Yuan (邴原) walked upon a string of cash coins while strolling and incapable of discovering the owner hung it up in a nearby tree, as other passerby's noticed this string they also began hanging coins up in the tree with the assumption that it was a holy tree and made wishes for wealth and luck. The earliest money trees however date back to the Han dynasty in present-day Sichuan where at the time a Taoist religious order named the Way of the Five Pecks of Rice, the money trees uncovered by archeologists have been known to be as tall as 198 centimeters, other than being decorated with many strings of cash coins these money trees were also decorated with little bronze dogs, bats, Chinese deities, elephants, deer, phoenixes, and dragons and had a foundation made from pottery but a body made from bronze. Both the inscriptions and calligraphy found on Chinese money trees match those of contemporary Chinese cash coins and those from the Han dynasty typically featured replicas of Wu Zhu (五銖) coins while those from the three kingdoms period had inscriptions such as Liang Zhu (兩銖).[204][205][206][207][208]

Taoist Charms

.jpg)

Taoist charms (Traditional Chinese: 道教品壓生錢; Simplified Chinese: 道教品压生钱; Pinyin: dào jiào pǐn yā shēng qián) are Chinese numismatic charms that contain inscriptions and images related to Taoism. As the people of Imperial China often believed that fortune both good and bad were the results of the spirits interfering with them they attempted to scare evil spirits away just as they would hostile humans. Since early history the Chinese had attributed magical powers and influence to Hanzi characters believing that certain characters could impact spirits, in fact the Huainanzi described that the spirits were horror-stricken of being commanded by the magical powers of the Hanzi characters which were used for amulets and charms, this is possibly due to the fact that the majority of the population of China was illiterate for most of its history. Many early Han dynasty charms and amulets were worn as pendants containing inscriptions requesting that people who were deified in the Taoist religion to lend them protection. Some Taoist charms contain inscriptions based on "Taoist magic writing" (Chinese: 符文, also known as Taoist magic script characters, Taoist magic figures, Taoist magic formulas, Taoist secret talismanic writing, and Talismanic characters) which is a secret writing style written down by Fulu. The "Records of the Divine Talismans of the Three Grottoes" (三洞神符紀) attribute the origin of Taoist "magic writing" to clouds condensing, the technique of learning Taoist "magic writing" is passed down from Taoist priests to their students and differ from Taoist sect to Taoist sect, these characters are composed of twisted strokes that at times may look like Hanzi characters. The secrecy of Taoist "magic writing" made many people to think that Chinese charms and amulets that contained them would have more effect in controlling the will of the spirits. As the majority of these Chinese charms asked the Taoist God of Thunder to kill the evil spirits or bogies, these numismatic charms are often called to "Lei Ting" charms (雷霆錢) or "Lei Ting curse" charms. As imperial decrees had absolute authority this proliferated the myth that the general populace held that Hanzi characters were somehow magical which in turn inspired Chinese charms and amulets to take the forms of imperial decrees. Many Taoist charms and amulets read as if it were by a high rank official commanding the evil spirits and bogies with inscriptions such as "let it (the command) be executed as fast as Lü Ling.",[lower-alpha 4] "quickly, quickly, this is an order", and "(pay) respect (to) this command".[209] Taoist charms and amulets can contain either square holes and round ones, many Taoist amulets and charms contain images of Liu Haichan, Zhenwu, the Bagua, Yin Yang symbols, constellations, Laozi, swords, bats, and immortals.[210][211][212][213][214][215]

During the Song dynasty a number of Taoist charms depicting the “Quest for Longevity” were cast, these Taoist charms contain images of an immortal, incense burner, crane, and a tortoise on the obverse and Taoist "magic writing" on the reverse. Taoist charms containing the quest for immortality are quite a common motif and reproductions of this charm were commonly made after the Song period.[216] Some Taoist charms from the Qing dynasty contain images of Lü Dongbin with the inscription fú yòu dà dì (孚佑大帝, “Great Emperor of Trustworthy Protection”), this charm notably contains a round hole rather than a square one as is typical of most Chinese numismatic charms.[217][218]

A Taoist charm from either the Jin or Yuan dynasty without any written text shows what is commonly believed to be either a "boy under a pine tree" (松下童子) or a "boy worshipping an immortal" (童子拜仙人), but there's an alternative hypothesis that this charm depicts a meeting between Laozi and Zhang Daoling, this hypothesis is based on the fact that the figure supposedly representing Zhang Daoling is carrying a cane which in Mandarin Chinese is a homophone for Zhang. On the reverse side of the charm are the twelve Chinese zodiacs, each zodiac is in a circle surrounded by what in the Chinese numismatic charms world is referred to as "auspicious clouds" which number eight as this is considered a "lucky" number in China.[219]

Chinese charms with coin inscriptions

Chinese charms with coin inscriptions (Traditional Chinese: 錢文錢; Simplified Chinese: 钱文钱; Pinyin: qián wén qián) were Chinese numismatic charms that used the contemporary inscriptions of circulating Chinese cash coins, these types of charms have a large overlap with other categories of Chinese charms and amulets but use the official inscriptions of government cast coinage due to the mythical association of Hanzi characters and magical powers as well as the cultural respect for the authority of the government which gave more credence to government decrees and orders including those on coins, for this reason even regular cash coins have had been attributed supernatural qualities in various cultural phenomenon such as folk tales and Feng shui. Various official coin inscriptions already have very auspicious meanings which is also why these inscriptions were selected to be used on Chinese numismatic charms and amulets, during times of crisis and disunity such as under the reign of Wang Mang the number of charms with coin inscriptions seem to increase enormously.[220][221][222] Meanwhile, other Chinese cash coin inscriptions were selected due to a perceived force in the metal used in the casting of these contemporary cash coins, an example would be the Later Zhou dynasty era zhōu yuán tōng bǎo (周元通寶) charm based on cash coins with the same inscription. Even long after the fall of the Xin dynasty charms with inscriptions from Wang Mang era coinage, and charms were produced with inscriptions like the Northern Zhou era wǔ xíng dà bù (五行大布) because it could be translated as "5 elements coin", the Later Zhou dynasty's zhōu yuán tōng bǎo (周元通寶), the Song dynasty era tài píng tōng bǎo (太平通寶), the Khitan Liao dynasty era qiān qiū wàn suì (千秋萬歲, "thousand autumns and ten thousand years"), as well as the Jurchen Jin dynasty era tài hé zhòng bǎo (泰和重寶). Northern Song dynasty era charms may have been based on actual Mother coins that were used to produce the official cash coins produced by the government but were given different reverses to make them into charms.[223][224] During the Ming dynasty there were Chinese charms based on the hóng wǔ tōng bǎo (洪武通寶) with an image of a boy (or possible the Emperor) riding either an ox or water buffalo, this charm became very popular as the first Emperor of the Ming dynasty was born as a peasant and spent his early life as one and eventually attained the title of Emperor which inspired many people that they could also do great things despite their lowly birth. There were also a large number of Chinese numismatic charms cast with the reign title Zheng De (正德通寶), despite the government having deprecated cash coins for paper money at the time and these charms were often given to children as gifts.[225] During the Manchu Qing dynasty a charm was cast with the inscription qián lóng tōng bǎo (乾隆通寶), but was fairly larger and had the tōng bǎo (通寶) part of the cash coin written in a slightly different style as well as had the Manchu characters on its reverse indicating its place of origin rotated 90 degrees. Some charms were also made to resemble the briefly cast qí xiáng zhòng bǎo (祺祥重寶) cash coins. Later charms were made to resemble the guāng xù tōng bǎo (光緒通寶) cast under the Guangxu Emperor but had dīng cái guì shòu (丁財貴壽, "May you acquire wealth, honor (high rank) and longevity") written on the reverse side of the coin.[226][227][228][229][230][231][232]

Ming dynasty cloisonné charms

_-_Scott_Semans.png)

Ming dynasty cloisonné charms (Traditional Chinese: 明代景泰藍花錢; Simplified Chinese: 明代景泰蓝花钱; Pinyin: míng dài jǐng tài lán huā qián) are extremely scarce Chinese numismatic charms made from cloisonné rather than brass or bronze which is used for the majority of charms and amulets from China, or silver which was used during the late imperial period. A known cloisonné charm from the Ming dynasty has the inscription nā mó ē mí tuó fó (南無阿彌陀佛 , "I put my trust in Amitābha Buddha"), there are various cloured lotus blossoms between the Hanzi characters, each colour represents something different while the white lotus symbolises the earth's womb from which everything is born, this was also the symbol of the Ming dynasty itself. Another known Ming dynasty era cloisonné charm has the inscription wàn lì nián zhì (萬歷年制, "Made during the (reign) of Wan Li") and the eight Buddhist treasure symbols impressed between the Hanzi characters, these Buddhist treasure symbols are the umbrella, the conch shell, the flaming wheel, the endless knot, a pair of fish, the treasure vase,[lower-alpha 5] the lotus, and the Victory Banner.[233][234][235][236]

It is popular for Chinese numismatic cloisonné charms from after the Ming dynasty (especially cloisonné charms produced in the Qing dynasty) to have flower patterns.[237]

Chinese charms with musicians, dancers, and acrobats

Chinese charms with "barbarian" musicians, dancers, and acrobats (Traditional Chinese: 胡人樂舞雜伎錢; Simplified Chinese: 胡人乐舞杂伎钱; Pinyin: hú rén yuè wǔ zá jì qián) appeared during either the Khitan Liao or the Chinese Song dynasty new Chinese numismatic charms appeared that featured "barbarians" as musicians, dancers, and acrobats. These charms generally depict four individuals of which one is doing an acrobatic stunt such as the handstand while all others are playing various musical instruments; one of which is a four string instrument which might possibly be a ruan, another plays the flute, and the other plays on musical instrument known as the wooden fish. Despite the fact that most numismatic catalogues refer to these charms as depicting "barbarians" or Huren (胡人, literally "bearded people") the characters depicted on these charms notably have no beards. The reverse side of these charms depict four children or babies playing and enjoying themselves which is a common feature for Liao dynasty charms, above these babies is a person resembling a baby that appears to ride on something.[238][239][240][241]

Chinese treasure bowl charms

Chinese treasure bowl charms are Chinese numismatic charms that feature references to the mythical treasure bowl (聚寶盆) which would usually grant unending wealth to those who hold it but may also be responsible for great sorrow. These charms are pendants with an image of the mythical treasure bowl filled with various treasures from the eight treasures on one side and the inscription píng ān jí qìng (平安吉慶, "Peace and Happiness") on the other. The loops of these charms are a dragon and the string would be placed between the legs and the tail of the dragon, while at the bottom of these charms is the dragon's head looking upwards.[242][243]

Chinese poem coins

Chinese poem coins (Traditional Chinese: 詩錢; Simplified Chinese: 诗钱; Pinyin: shī qián, alternatively 二十錢局名) were Chinese cash coins cast under the Kangxi Emperor,[244][245] a Manchu Emperor known for his Chinese poetry skills and wrote the work "Illustrations of Plowing and Weaving" (耕織圖) in 1696. Under the Kangxi Emperor 23 mints operated at various times with many closing and reopening, the coins produced under the Kangxi Emperor all had the obverse inscription Kāng Xī Tōng Bǎo (康熙通寶) and had the Manchu character ᠪᠣᠣ (Boo, building) written on the left side of the square hole and the name of the mint in Chinese on the right. As the name Kangxi was composed of the characters meaning "health" (康) and "prosperous" (熙)[246][247][248][249] the Kāng Xī Tōng Bǎo cash coins were already viewed as having auspicious properties by the Chinese people. As the Kāng Xī Tōng Bǎo cash coins were produced at various mints some people placed these coins together to form poems, even though many of these poems did not have any meaning they were composed in adherence to the rules of Classical Chinese poetry. These coins were always placed together to form the following poems:

| Traditional Chinese | Pinyin |

|---|---|

| 同福臨東江 | tóng fú lín dōng jiāng |

| 宣原蘇薊昌 | xuān yuán sū jì chāng |

| 南寧河廣浙 | nán níng hé guǎng zhè |

| 台桂陝雲漳 | tái guì shǎn yún zhāng |

According to an old Chinese superstition the strung "charm" of twenty coins also known as "set coins" (套子錢) only worked if all coins were genuine and this could be tested by placing them on a chicken-coop and if the cocks did not crow during the early morning. As carrying twenty coins together was seen as less than convenient new charms were being produced that had the ten of the twenty mint marks on each side of the coin, unlike the actual cash coins that they're based on these charms tend to have round holes in the middle and are also round in shape. Sometimes they were painted red as the colour red is viewed to be auspicious in Chinese culture. Sometimes these coins had obverse inscriptions wishing for good fortunes and the twenty mint marks on their reverse, these inscriptions include:

| Traditional Chinese | Translation |

|---|---|

| 金玉滿堂 | "may gold and jade fill your halls." |

| 大位高升 | "may you be promoted to a high position." |

| 五子登科 | "may your five sons achieve great success in the imperial examinations." |

| 福祿壽喜 | "good fortune, emolument (official salary), longevity, and happiness." |

| 吉祥如意 | "may your good fortune be according to your wishes." |

Kāng Xī Tōng Bǎo cash coins produced at the Ministry of Revenue and the Ministry of Public Works in the capital city of Beijing are excluded from these poems.[250][251][252]

Buddhist charms and temple coins

_01.jpg)

Buddhist charms (Traditional Chinese: 佛教品壓勝錢; Simplified Chinese: 佛教品压胜钱; Pinyin: fó jiào pǐn yā shēng qián) are Chinese numismatic charms that display Buddhist symbols of mostly Mahayana Buddhism. These charms can have inscriptions in both Chinese and Sanskrit (while those with Sanskrit inscriptions didn't start appearing until the Ming dynasty),[253][254] these charms generally contain blessings from the Amitābha Buddha such as coins with the inscription ē mí tuó fó (阿彌陀佛). Temple coins often had inscriptions calling for compassion and requesting for the Buddha to protect the holder of the coin, most temple coins tend to be diminutive in size, some temple coins contan mantras from the Heart Sūtra. Some Buddhist charms are pendants dedicated to the Bodhisattva Guanyin, many contain the image of a lotus which is traditionally associated with the Buddha, and cooking bananas associated with Vanavasa. Less commonly some Buddhist charms also contain Taoist symbolism including the Taoist "magic writing" secret script. There are Buddhist charms based on the Ming dynasty era hóng wǔ tōng bǎo (洪武通寶) but larger.

Japanese Buddhist charms in China

The Buddhist qiě kōng cáng qì (且空藏棄) Japanese numismatic charm cast during the years 1736-1740 in Japan during the Tokugawa shogunate dedicated to the Ākāśagarbha Bodhisattva based on one of the favourite mantras of Kūkai is frequently found in China. Ākāśagarbha one of the 8 immortals who attempts to free people from the cycle of reincarnation with compassion. These coins were brought to China in large numbers by Japanese Buddhist monks, another Japanese Buddhist charm frequently found in China has the inscription nā mó ē mí tuó fó (南無阿彌陀佛, "I put my trust in (the) Amitābha Buddha").[255][256][257]

Chinese Boy charms

Chinese Boy charms (Traditional Chinese: 童子連錢; Simplified Chinese: 童子连钱; Pinyin: tóng zǐ lián qián) are Chinese numismatic charms that depict images of boys in the hope that these charms would cause more boys to be born in the family of the holder, they usually have an eyelet to be carried, hung, or worn. As the traditional ideal for a Chinese family was to have five sons and only two daughters boys were the preferred sex, this was because of a multitude of factors including but not limited to the fact that males are to carry out the Confucian ideal of filial piety, performing ancestor worship and continuing the family line, as well take care of their parents when they grow up. Many families hoped that at least one of their sons would be succeed to pass the imperial examination system and attain the honourable rank of Mandarin. Often the boys depicted on Chinese boy charms were in a position of reverence, and these little statuettes of boys are found on top of traditional Chinese numismatic charm designs, these charms are more commonly found in Southern China. Some boy charms contain inscriptions like tóng zǐ lián qián (童子連錢) which connect male offspring to monetary wealth, boy statuettes belonging to boy charms can also be found on top of open-work charms. Some boy charms contain images of lotus seeds because the Chinese word for lotus sounds similar to "continuous" wishing for continuous amount of sons being born.[258][259][260][261]

Chinese astronomy coins