Taiping Heavenly Kingdom

| Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace 太平天囯 Tàipíng Tiānguó | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1851–1864 | |||||||||

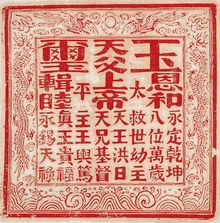

Royal Seal

| |||||||||

|

Greatest extent (maroon) of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. | |||||||||

| Capital | Tianjing (天京) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Chinese | ||||||||

| Religion |

Official: God Worshipping Unofficial: | ||||||||

| Government | Heterodox Christian Theocratic Absolute Monarchy | ||||||||

| Taiping Heavenly King (太平天王) | |||||||||

• 1851–1864 | Hong Xiuquan | ||||||||

• 1864 | Hong Tianguifu | ||||||||

| Kings | |||||||||

| Historical era | Qing dynasty | ||||||||

| January 11 1851 | |||||||||

• Capture of Nanking | March 1853 | ||||||||

| 1856 | |||||||||

• Death of Hong Tianguifu | November 18 1864 | ||||||||

| Currency | Holy Treasure (聖寶 shengbao) (cash) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of |

| ||||||||

| Taiping Heavenly Kingdom | |||||||||||

Royal seal of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 太平天國1 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 太平天囯 | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning |

Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace Greatly Peaceful Heavenly Kingdom | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, officially the Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace, was an oppositional state in China from 1851 to 1864, supporting the overthrow of the Qing dynasty by Hong Xiuquan and his followers. The unsuccessful war it waged against the Qing is known as the Taiping Rebellion. Its capital was at Tianjing (present-day Nanjing).

A self-proclaimed convert to Christianity, Hong Xiuquan led an army that controlled a significant part of southern China during the middle of the 19th century, eventually expanding to a size of nearly 30 million people. The rebel kingdom announced social reforms and the replacement of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Chinese folk religion by his form of Christianity, holding that he was the second son of God and the younger brother of Jesus. The Taiping areas were besieged by Qing forces throughout most of the rebellion. The Qing government defeated the rebellion with the eventual aid of French and British forces.

Background

In the mid-19th century, China under the Qing dynasty suffered a series of natural disasters, economic problems, and defeats at the hands of the Western powers—in particular, the humiliating defeat in 1842 by the British in the First Opium War. The war disrupted shipping patterns and threw many out of work. It was these disaffected who flocked to join the charismatic visionary Hong Xiuquan.

Beginning with Robert Morrison in 1807, Protestant missionaries began working from Macao, Pazhou (known at the time as "Whampoa"), and Guangzhou ("Canton"). Their household staff and the printers they employed for Morrison's dictionary and translation of the Bible—men like Cai Gao, Liang Afa, and Qu Ya'ang—were their first converts and suffered greatly, being repeatedly arrested, fined, and driven into exile at Malacca. However, they corrected and adapted the missionaries' message to reach the Chinese, printing thousands of tracts of their own devising. Unlike the westerners, they were able to travel through the interior of the country and began to particularly frequent the prefectural and provincial examinations, where local scholars competed for the chance to rise to power in the imperial civil service. One of the native tracts, Liang's nine-part, 500-page tome called Good Words to Admonish the Age, found its way into the hands of Hong Xiuquan in the mid-1830s, although it remains a matter of debate during which exact examination this occurred. Hong initially leafed through it without interest.

After several failures during the examinations, however, Hong told friends and family of a dream in which he was greeted by a golden-haired, bearded man who presented him with a sword and a younger man whom he addressed as "Elder Brother". Hong worked in his village another six years as a tutor before his brother convinced him that Liang's tract was not like the others and was worth examination. When he read the tract he saw his long-past dream in terms of Christian symbolism: he was the younger brother of Jesus and had met God the Father. He now felt it was his duty to spread Christianity and overthrow the Qing dynasty. He was joined by Yang Xiuqing, a former charcoal and firewood salesman of Guangxi, who claimed to act as a voice of God to direct the people and gain political power.[1]

Feng Yunshan formed the Society of God Worshippers (Chinese: 拜上帝会; pinyin: Bài Shàngdì Huì), in Guangxi after a missionary journey there in 1844 to spread Hong's ideas.[2] In 1847, Hong became the leader of the secret society.[3] The Taiping faith, inspired by missionary Christianity, says one historian, "developed into a dynamic new Chinese religion... Taiping Christianity". Hong presented this religion as a revival and a restoration of the ancient classical faith in Shangdi, a faith that had been displaced by Confucianism and dynastic imperial regimes.[4] The sect's power grew in the late 1840s, initially suppressing groups of bandits and pirates, but persecution by Qing authorities spurred the movement into a guerrilla rebellion and then into civil war.

History

Establishment

The Taiping Rebellion began in 1850 in Guangxi. On January 11, 1851 (the 11th day of the 1st lunar month), incidentally Hong Xiuquan's birthday, Hong declared himself "Heavenly King" of a new dynasty, the "Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace".[5] After minor clashes, the violence escalated into the Jintian Uprising in February 1851, in which a 10,000-strong rebel army routed and defeated a smaller Qing force. Feng Yushan was to be the strategist of the rebellion and the administrator of the kingdom during its early days, until his death in 1852.[6]

In 1853 the Taiping forces captured Nanjing, making it their capital and renaming it Tianjing ("Heavenly Capital"). Hong converted the office of the Viceroy of Liangjiang into his Palace of Heavenly King. Since Hong Xiuquan had been supposedly instructed in his dream to exterminate all "demons", which was what the Taipings considered the Manchus to be, thus they set out to kill and wipe out the entire Manchu population. When Nanjing was occupied, the Taipings went on a rampage killing, burning and hacking 40,000 Manchus to death in the city[7] They first killed all the Manchu men, then forced the Manchu women outside the city and burnt them to death.[8]

At its height, the Heavenly Kingdom controlled south China, centered on the fertile Yangtze River Valley. Control of the river meant that the Taiping could easily supply their capital. From there, the Taiping rebels sent armies west into the upper reaches of the Yangtze, and north to capture Beijing, the capital of the Qing dynasty. The attempt to take Beijing failed.

Internal conflict

In 1853 Hong withdrew from active control of policies and administration, ruling exclusively by written proclamations often in religious language. Hong disagreed with Yang in certain matters of policy and became increasingly suspicious of Yang's ambitions, his extensive network of spies, and his declarations when "speaking as God". Yang and his family were put to death by Hong's followers in 1856, followed by the killing of troops loyal to Yang.[9]

With their leader largely out of the picture, Taiping delegates tried to widen their popular support with the Chinese middle classes and forge alliances with European powers, but failed on both counts. The Europeans decided to stay neutral. Inside China, the rebellion faced resistance from the traditionalist middle class because of their hostility to Chinese customs and Confucian values. The land-owning upper class, unsettled by the Taiping rebels' peasant mannerisms and their policy of strict separation of the sexes, even for married couples, sided with the Qing forces and their Western allies.

In 1859 Hong Rengan, a cousin of Hong, joined the Taiping Rebellion in Nanjing, and was given considerable power by Hong. He developed an ambitious plan to expand the kingdom's boundaries. In 1860 the Taiping rebels were successful in taking Hangzhou and Suzhou to the east (See also: Second rout of the Army Group Jiangnan), but failed to take Shanghai, which marked the beginning of the decline of the Kingdom.

Fall

An attempt to take Shanghai in August 1860 was initially successful but finally repulsed by a force of Chinese troops and European officers under the command of Frederick Townsend Ward.[6] This army would later become the "Ever Victorious Army", led by "Chinese" Gordon, and would be instrumental in the defeat of the Taiping rebels. Imperial forces were reorganized under the command of Zeng Guofan and Li Hongzhang, and the Qing government's reconquest began in earnest. By early 1864, Qing control in most areas was well established.

Hong declared that God would defend Nanjing, but in June 1864, with Qing forces approaching, he died of food poisoning as the result of eating wild vegetables as the city began to run out of food. He was sick for twenty days before the Qing forces could take the city. Only a few days after his death the Qing forces took the city. His body was buried and was later exhumed by Zeng to verify his death, and cremated. Hong's ashes were later blasted out of a cannon in order to ensure that his remains have no resting place as eternal punishment for the uprising.

Four months before the fall of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, Hong Xiuquan abdicated in favour of Hong Tianguifu, his eldest son, who was 15 years old then. Hong Tianguifu was unable to do anything to restore the kingdom, so the kingdom was quickly destroyed when Nanjing fell in July 1864 to Qing forces after vicious fighting in the streets. Most of the so-called princes were executed by Qing officials in Jinling Town (金陵城), Nanjing.

Although the fall of Nanjing in 1864 marked the destruction of the Taiping regime, the fight was not yet over. There were still several thousands of Taiping rebel troops continuing the fight. It took seven years to finally put down all remnants of the Taiping Rebellion. In August 1871 the last Taiping rebel army, led by Shi Dakai's commander, Li Fuzhong (李福忠), was completely wiped out by the Qing forces in the border region of Hunan, Guizhou and Guangxi.

Administration

The Heavenly King was the highest position in the Heavenly Kingdom. The sole people to hold this position were Hong Xiuquan and his son Hong Tianguifu:

| Personal Name | Period of Reign | Era Names (and their according range of years) |

|---|---|---|

Ranked below the "King of Heaven" Hong Xiuquan, the territory was divided among provincial rulers called kings or princes; initially there were five – the Kings of the Four Cardinal Directions and the Flank King). Of the original rulers, the West King and South King were killed in combat in 1852. The East King was murdered by the North King during a coup in 1856, and the North King himself was subsequently killed. The Kings' names were:

- South King (南王), Feng Yunshan (died 1852)

- East King (東王), Yang Xiuqing (died 1856)

- West King (西王), Xiao Chaogui (died 1852)

- North King (北王), Wei Changhui (died 1856)

- Flank King (翼王), Shi Dakai (captured and executed by Qing forces in 1863)

The later leaders of the movement were 'Princes':

- Zhong Prince (忠王), Li Xiucheng (1823 – 1864, captured and executed by Qing forces)

- Ying Prince (英王), Chen Yucheng (1837 – 1862)

- Gan Prince (干王), Hong Rengan (1822 – 1864; cousin of Hong Xiuquan, executed)

- Jun Prince (遵王), Lai Wenkwok (1827 – 1868)

- Fu Prince (福王), Hong Renda (洪仁達; Hong Xiuquan's second-eldest brother; executed by Qing forces in 1864)

- Tian Gui (田貴; executed in 1864)

Other princes include:

- An Prince (安王), Hong Renfa (洪仁發), Hong Xiuquan's eldest brother

- Yong Prince (勇王), Hong Rengui (洪仁貴)

- Fu Prince (福王), Hong Renfu (洪仁富)

In the later years of the Taiping Rebellion, the territory was divided among many, for a time into the dozens, of provincial rulers called princes, depending on the whims of Hong.

Captured areas in Jiangsu were called “Sufu Province”.

Policies

Within the land that it controlled, the Taiping Heavenly Army established a totalitarian, theocratic, and highly militarized rule.[10]

- The subject of study for the examinations for officials changed from the Confucian classics to the Bible.

- Private property ownership was abolished and all land was held and distributed by the state.[11]

- A solar calendar replaced the lunar calendar.

- Foot binding was banned. (The Hakka people had never followed this tradition, and consequently the Hakka women had always been able to work the fields.[12])

- Society was declared classless and the sexes were declared equal. At one point, for the first time in Chinese history civil service exams were held for women. Some sources record that Fu Shanxiang, an educated woman from Nanjing, passed them and became an official at the court of the Eastern King.

- The sexes were rigorously separated.[13] There were separate army units consisting of women only; until 1855, not even married couples were allowed to live together or have sexual relations.[14]

- The Qing-dictated queue hairstyle was abandoned in favor of wearing the hair long.

- Other new laws were promulgated including the prohibition of opium, gambling, tobacco, alcohol, polygamy (including concubinage), slavery, and prostitution. These all carried death penalties.

Hong Rengan's proposed reforms

In 1859 the Gan Prince Hong Rengan, with the approval of his cousin the Heavenly King, advocated several new policies, including:[15]

- Promoting the adoption of railways by granting patents for the introduction of locomotives; 21 railways were planned for each of the 21 provinces.

- Promoting the adoption of steamships for commerce and defence.

- Establishment of currency-issuing private banks.

- Granting of 10-year patents for introduction of new inventions, 5-year for minor items.

- Establishment of a National Postal Service.

- Promoting mineral exploration by granting control and twenty percent of the revenue to the discoverers of deposits.

- Introduction of governmental investigative officers.

- Introduction of independent impartial state media officers for reporting and disseminating news.

- Institution of district treasuries and paymasters to manage finances.

Military equipment

Taiping Tianguo soldiers seem to have been partially equipped with surplus equipment sold by various Western companies and military units' stores, both small arms and artillery. One shipment of weaponry from an American dealer in April 1862 was listed as 2,783 (percussion cap) muskets, 66 carbines, 4 rifles, and 895 field artillery guns.[16]

Religious affairs

Initially, the followers of Hong Xiuquan were called God Worshippers. Hong's faith was inspired by visions he reported in which the Christian Lord greeted him in Heaven. Hong had earlier been in contact with Protestant missionaries and read the Bible. Officially, the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom endorsed Hong Xiuquan's own version of Christianity combined with elements of Chinese folk religion, the "restored faith" in Shingdu and some other native beliefs. Although Hong's followers led the Kingdom, there were also adherents of Buddhism, Chinese folk religion and other religious traditions native to China.

The movement's founder, Hong Xiuquan, had failed the imperial examinations numerous times. After one such failure in 1836, Hong overheard a Protestant missionary, most probably Edwin Stevens[17], preaching and took home some Chinese translations of Bible tracts, including a pamphlet entitled Good Words for Exhorting the Age by Liang Fa. Hong and his cousin were both baptized in accordance with Liang's directions.[18] In 1843, after Hong's final failure at the exams, he had what some regard as a nervous breakdown and others as a mystical revelation, connecting his in-depth readings of the Christian tracts to strange dreams he had been having for the past six years. In his dreams, a bearded man with golden hair and a black robe called himself Jehovah, gave him a sword, and taught him to slay demons beside a younger man whom Hong addressed as "Elder Brother".[19]

Hong Xiuquan came to believe that the figures in his dreams were God the Father and Jesus Christ the Son, and that they were revealing his destiny as a slayer of demons and the leader of a new Heavenly Kingdom on Earth.[20] The demons were later interpreted by him to be the Qing and false religions.

Hong developed a literalist understanding of the Bible, producing a set of his own annotations. He rejected the doctrine of the Trinity, saying "God is the Father and embodies myriads of phenomena; Christ is the Son, who was manifest in the body... The Wind of the Holy Spirit, God, is also a Son... God is one who gives shapes to things, molds things into forms, who created heaven and created earth, who begins and ends all things, yet has no beginning or end himself..." and "God and the Savior are one."[21]

Currency

In its first year, the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom minted coins that were 23 mm to 26 mm in diameter, weighing around 4.1 g. The kingdom's name was inscribed on the obverse and "Holy Treasure" (Chinese: 聖寶) on the reverse; the kingdom also issued paper notes.[22]

Impact on Hakkas

With the collapse of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, the Qing Dynasty launched waves of massacres against the Hakkas, killing up to 30,000 each day during the height of the massacres.[23] Another major impact was the bloody Punti-Hakka Clan Wars (1855 and 1867), which would cause the deaths of a million people.[24]

See also

- Eastern Lightning, a Sect with a similar origin as Taiping Heavenly Kingdom

Notes

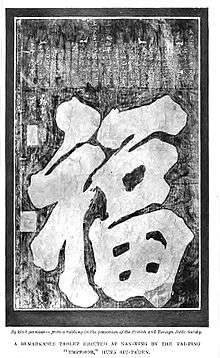

- 1Note that the uncommon variant character 囯 is used, as opposed to the more common 國 (and later, 国). The Taiping used wang (王, "king") in the center of their character, as opposed to the traditional Chinese huo (或, "or", used as a phonetic marker) or the later simplified Chinese yu (玉, "jade").

- Note also that

References

Citations

- ↑ Spence (1990), p. p. 171.

- ↑ "Feng Yunshan (Chinese rebel leader) - Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- ↑ "Taiping Rebellion (Chinese history) - Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- ↑ Reilly (2004), p. 4.

- ↑ China: A New History, John King Fairbank and Merle Goldman. Harvard, 2006.

- 1 2 Spence (1996)

- ↑ Matthew White (2011). Atrocities: The 100 Deadliest Episodes in Human History. W. W. Norton. p. 289. ISBN 978-0-393-08192-3.

- ↑ Reilly (2004), p. 139.

- ↑ Spence 1996, p. 243

- ↑ Franz H. Michael, The Taiping Rebellion: History 190-91 (1966)

- ↑ Pamela Kyle Crossley, The Wobbling Pivot: China Since 1800 105 (2010)

- ↑ Spence 1996, p. 25

- ↑ Pamela Kyle Crossley, The Wobbling Pivot: China Since 1800 105 (2010)

- ↑ Spence 1996, p. 234

- ↑ Teng, Ssu-yü; Fairbank, John King (1979). China's Response to the West: A Documentary survey 1839-1923. Harvard University Press. pp. 57–59. ISBN 0674120256.

- ↑ Spence, Jonathan D. (1996). God's Chinese Son: The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom of Hong Xiuquan. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 311. ISBN 0393285863.

- ↑ Spence (1996), p. 31.

- ↑ Michael (1966), p. 25.

- ↑ Spence (1996), p. 171-172.

- ↑ Wsu.edu. "Wsu.edu." Taiping Rebellion. Retrieved on 11 April 2007.

- ↑ Michael (1966), p. 138.

- ↑ "Money of the Kingdom of Heavenly Peace". The Currency Collector. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ↑ The Hakka Odyssey & their Taiwan homeland - Page 120 Clyde Kiang - 1992

- ↑ Mark Anthony Chang, Hakka–Punti Clan Wars, Guangdong, China, 1855-1867 Geni

Sources

- Works cited

- Reilly, Thomas H. (2004). The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom: Rebellion and the Blasphemy of Empire. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295984309.

- Spence, Jonathan (1996), God's Chinese Son, New York: Norton, ISBN 0-393-03844-0

- ——— (1990), The Search for Modern China, New York: Norton

Further reading

For a fuller selection, please see the section Taiping Rebellion: Further reading

- Platt, Stephen R. (2012). Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom: China, the West, and the Epic Story of the Taiping Civil War. New York: Knopf. ISBN 9780307271730. Narrative history, with emphasis on the military aspects.

- Kuhn, Philip A. (1970), "The Taiping Rebellion", in Fairbank, John K., Cambridge History of China, Cambridge: Cambridge Univ Press, pp. 264–350 .

- Michael, Franz H. (1966). The Taiping Rebellion: History and Documents. Seattle,: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295739592.

External links

- 撕下历史的“面膜”——读潘旭澜教授《太平杂说》 (in Chinese)