Monkey

| Monkeys Fossil range: Late Eocene–Present[1] | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Included groups | ||||||||||||

| Cladistically included but traditionally excluded groups | ||||||||||||

Monkeys or simians are basal Haplorhini as sister of the Tarsiiformes. It consists of the Catarrhini and Platyrrhini (New World monkeys), and other extinct groups. The Catarrhini contains the Cercopithecoidea (Old World monkeys) and the Hominoidea (apes).[3][4] Many monkey species are tree-dwelling (arboreal), although there are species that live primarily on the ground, such as baboons. Most species are also active during the day (diurnal). Monkeys are generally considered to be intelligent, particularly Catarrhini.

Simians and tarsiers emerged within haplorrhines some 60 million years ago. New World monkeys and catarrhine monkeys emerged within the simians some 35 million years ago. Old World monkeys and Hominoidea emerged within the catarrhine monkeys some 25 million years ago. Extinct basal simians such as Aegyptopithecus or Parapithecus [35-32 million years ago] are also considered monkeys by primatologists.

Lemurs, lorises, and galagos are not monkeys; instead they are strepsirrhine primates. Like monkeys, tarsiers are haplorhine primates; however, they are also not monkeys.

Apes emerged within the catarrhines with the Old World monkeys as a sister group, so cladistically they are monkeys as well. Traditionally apes were not considered monkeys, rendering this grouping paraphyletic.

Historical and modern terminology

According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, the word "monkey" may originate in a German version of the Reynard the Fox fable, published circa 1580. In this version of the fable, a character named Moneke is the son of Martin the Ape.[5] In English, no very clear distinction was originally made between "ape" and "monkey"; thus the 1910 Encyclopædia Britannica entry for "ape" notes that it is either a synonym for "monkey" or is used to mean a tailless humanlike primate.[6] Colloquially, the terms "monkey" and "ape" are widely used interchangeably.[7] Also, a few monkey species have the word "ape" in their common name, such as the Barbary ape.

Later in the first half of the 20th century, the idea developed that there were trends in primate evolution and that the living members of the order could be arranged in a series, leading through "monkeys" and "apes" to humans.[8] Monkeys thus constituted a "grade" on the path to humans and were distinguished from "apes".

Scientific classifications are now more often based on monophyletic groups, that is groups consisting of all the descendants of a common ancestor. The New World monkeys and the Old World monkeys are each monophyletic groups, but their combination was not, since it excluded hominoids (apes and humans). Thus the term "monkey" no longer referred to a recognized scientific taxon. The smallest accepted taxon which contains all the monkeys is the infraorder Simiiformes, or simians. However this also contains the hominoids (apes and humans), so that monkeys are, in terms of currently recognized taxa, non-hominoid simians. Colloquially and pop-culturally, the term is ambiguous and sometimes monkey includes non-human hominoids.[9] In addition, frequent arguments are made for a monophyletic usage of the word "monkey" from the perspective that usage should reflect cladistics.[10][11][12][13]

A group of monkeys may be commonly referred to as a tribe or a troop.[14]

Two separate groups of primates are referred to as "monkeys": New World monkeys (platyrrhines) from South and Central America and Old World monkeys (catarrhines in the superfamily Cercopithecoidea) from Africa and Asia. Apes (hominoids)—consisting of gibbons, orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, and humans—are also catarrhines but were classically distinguished from monkeys.[15][16][17][18] (Tailless monkeys may be called "apes", incorrectly according to modern usage; thus the tailless Barbary macaque is sometimes called the "Barbary ape".)

Description

Monkeys range in size from the pygmy marmoset, which can be as small as 117 millimetres (4.6 in) with a 172-millimetre (6.8 in) tail and just over 100 grams (3.5 oz) in weight,[19] to the male mandrill, almost 1 metre (3.3 ft) long and weighing up to 36 kilograms (79 lb).[20] Some are arboreal (living in trees) while others live on the savanna; diets differ among the various species but may contain any of the following: fruit, leaves, seeds, nuts, flowers, eggs and small animals (including insects and spiders).[21]

Some characteristics are shared among the groups; most New World monkeys have prehensile tails while Old World monkeys have non-prehensile tails or no visible tail at all. Old World monkeys have trichromatic color vision like that of humans, while New World monkeys may be trichromatic, dichromatic, or—as in the owl monkeys and greater galagos—monochromatic. Although both the New and Old World monkeys, like the apes, have forward-facing eyes, the faces of Old World and New World monkeys look very different, though again, each group shares some features such as the types of noses, cheeks and rumps.[21]

Classification

The following list shows where the various monkey families (bolded) are placed in the classification of living (extant) primates.

- ORDER PRIMATES

- Suborder Strepsirrhini: lemurs, lorises, and galagos

- Suborder Haplorhini: tarsiers, monkeys, and apes

- Infraorder Tarsiiformes

- Family Tarsiidae: tarsiers

- Infraorder Simiiformes: simians

- Parvorder Platyrrhini: New World monkeys

- Family Callitrichidae: marmosets and tamarins (42 species)

- Family Cebidae: capuchins and squirrel monkeys (14 species)

- Family Aotidae: night monkeys (11 species)

- Family Pitheciidae: titis, sakis, and uakaris (41 species)

- Family Atelidae: howler, spider, and woolly monkeys (24 species)

- Parvorder Catarrhini

- Superfamily Cercopithecoidea

- Family Cercopithecidae: Old World monkeys (135 species)

- Superfamily Hominoidea: apes

- Family Hylobatidae: gibbons ("lesser apes") (17 species)

- Family Hominidae: great apes (including humans, gorillas, chimpanzees, and orangutans) (7 species)

- Superfamily Cercopithecoidea

- Parvorder Platyrrhini: New World monkeys

- Infraorder Tarsiiformes

Cladogram with extinct families

Below is a cladogram with some extinct monkey families.[22][23][24] Generally, extinct non-hominoid simians, including early Catarrhines are discussed as monkeys as well as simians or anthropoidea,[15][16][17] which cladistically means that Hominoidea are monkeys as well, restoring monkeys as a single grouping. It is indicated approximately how many million years ago (Mya) the clades diverged into newer clades.[25][26][27][28] It is thought the New World monkeys started as a drifted "Old World monkey" group from the old world (probably Aftrica) to the new world (South America).[16]

| Haplorhini (64) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gallery

Relationship with humans

The many species of monkey have varied relationships with humans. Some are kept as pets, others used as model organisms in laboratories or in space missions. They may be killed in monkey drives (when they threaten agriculture) or used as service animals for the disabled.

In some areas, some species of monkey are considered agricultural pests, and can cause extensive damage to commercial and subsistence crops.[29] This can have important implications for the conservation of endangered species, which may be subject to persecution. In some instances farmers' perceptions of the damage may exceed the actual damage.[30] Monkeys that have become habituated to human presence in tourist locations may also be considered pests, attacking tourists.[31]

In religion and popular culture, monkeys are a symbol of playfulness, mischief and fun.

As service animals for the disabled

Some organizations train capuchin monkeys as service animals to assist quadriplegics and other people with severe spinal cord injuries or mobility impairments. After being socialized in a human home as infants, the monkeys undergo extensive training before being placed with a disabled person. Around the house, the monkeys assist with feeding, fetching, manipulating objects, and personal care.[32]

In experiments

The most common monkey species found in animal research are the grivet, the rhesus macaque, and the crab-eating macaque, which are either wild-caught or purpose-bred.[33][34] They are used primarily because of their relative ease of handling, their fast reproductive cycle (compared to apes) and their psychological and physical similarity to humans. Worldwide, it is thought that between 100,000 and 200,000 non-human primates are used in research each year,[34] 64.7% of which are Old World monkeys, and 5.5% New World monkeys.[35] This number makes a very small fraction of all animals used in research.[34] Between 1994 and 2004 the United States has used an average of 54,000 non-human primates, while around 10,000 non-human primates were used in the European Union in 2002.[35]

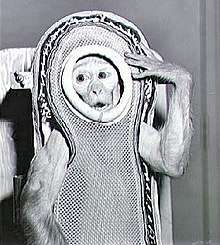

In space

A number of countries have used monkeys as part of their space exploration programmes, including the United States and France. The first monkey in space was Albert II, who flew in the US-launched V-2 rocket on June 14, 1949.[36]

As food

Monkey brains are eaten as a delicacy in parts of South Asia, Africa and China.[37] Monkeys are sometimes eaten in parts of Africa, where they can be sold as "bushmeat". In traditional Islamic dietary laws, the eating of monkeys is forbidden.[38]

Literature

.jpg)

Sun Wukong (the "Monkey King"), a character who figures prominently in Chinese mythology, is the protagonist in the classic comic Chinese novel Journey to the West.

Monkeys are prevalent in numerous books, television programs, and movies. The television series Monkey and the literary characters Monsieur Eek and Curious George are all examples.

Informally, the term "monkey" is often used more broadly than in scientific use and may be used to refer to apes, particularly chimpanzees, gibbons, and gorillas. Author Terry Pratchett alludes to this difference in usage in his Discworld novels, in which the Librarian of the Unseen University is an orangutan who gets very violent if referred to as a monkey. Another example is the use of Simians in Chinese poetry.

The winged monkeys are prominent characters in The Wizard of Oz.

Religion and worship

Monkey is the symbol of fourth Tirthankara in Jainism, Abhinandananatha.[39][40]

Hanuman, a prominent deity in Hinduism, is a human-like monkey god who is believed to bestow courage, strength and longevity to the person who thinks about him or Rama.

In Buddhism, the monkey is an early incarnation of Buddha but may also represent trickery and ugliness. The Chinese Buddhist "mind monkey" metaphor refers to the unsettled, restless state of human mind. Monkey is also one of the Three Senseless Creatures, symbolizing greed, with the tiger representing anger and the deer lovesickness.

The Sanzaru, or three wise monkeys, are revered in Japanese folklore; together they embody the proverbial principle to "see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil".[41]

The Moche people of ancient Peru worshipped nature.[42] They placed emphasis on animals and often depicted monkeys in their art.[43]

The Tzeltal people of Mexico worshipped monkeys as incarnations of their dead ancestors.

Zodiac

The Monkey (猴) is the ninth in the twelve-year cycle of animals which appear in the Chinese zodiac related to the Chinese calendar. The next time that the monkey will appear as the zodiac sign will be in the year 2028.[44]

See also

Notes

- ↑ When Carl Linnaeus defined the genus Simia in the 10th edition of Systema Naturae, it included all non-human monkeys and apes (simians).[2] Although "monkey" was never a taxonomic name, and is instead a vernacular name for a paraphyletic group, its members fall under the infraorder Simiiformes.

References

- ↑ Fleagle, J.; Gilbert, C. Rowe, N.; Myers, M., eds. "Primate Evolution: John Fleagle and Chris Gilbert". All the World's Primates. Primate Conservation, Inc. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ↑ Groves 2008, pp. 92–93.

- ↑ Naish, Darren. ""If Apes Evolved From Monkeys, Why Are There Still Monkeys?"". Scientific American Blog Network. Retrieved 2018-10-04.

- ↑ AronRa (2010-01-16), Turns out we DID come from monkeys!, retrieved 2018-10-04

- ↑ Harper, D. (2004). "Monkey". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2013-04-10.

- ↑ "Ape". Encyclopædia Britannica. XIX (11th ed.). New York: Encyclopædia Britannica. 1911. p. 160. Retrieved 2011-07-10.

- ↑ http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/monkey

- ↑ Dixson, A. F. (1981). The Natural History of the Gorilla. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-297-77895-0.

- ↑ Susman, Gary. "10 Best Monkeys at the Movies". Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 8, 2014.

- ↑ "If Apes Evolved From Monkeys, Why Are There Still Monkeys?".

- ↑ "Apes are monkeys, deal with it".

- ↑ "Are Humans Apes, Monkeys, Primates, or Hominims?".

- ↑ "Rehabilitating "Monkey"".

- ↑ "AskOxford: M". Collective Terms for Groups of Animals. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2008-10-20. Retrieved 2013-04-10.

- 1 2 Dobzhansky, Theodosius; Hecht, Max K.; Steere, William C. (2012-12-06). Evolutionary Biology. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9781468490633.

- 1 2 3 "Early Primate Evolution: The First Primates". anthro.palomar.edu. Retrieved 2017-08-12.

- 1 2 Bajpai, Sunil; Kay, Richard F.; Williams, Blythe A.; Das, Debasis P.; Kapur, Vivesh V.; Tiwari, B. N. (2008-08-12). "The oldest Asian record of Anthropoidea". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (32): 11093–11098. doi:10.1073/pnas.0804159105. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2516236. PMID 18685095.

- ↑ Delson, Eric; Tattersall, Ian; Couvering, John Van; Brooks, Alison S. (2004-11-23). Encyclopedia of Human Evolution and Prehistory: Second Edition. Routledge. ISBN 9781135582289.

- ↑ Nowak, R. M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World (6th ed.). Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0801857898.

- ↑ "Mandrill". ARKive. 2005. Retrieved 2013-04-10.

- 1 2 Fleagle, J. G. (1998). Primate Adaptation and Evolution (2nd ed.). Academic Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-0-12-260341-9.

- ↑ Nengo, Isaiah; Tafforeau, Paul; Gilbert, Christopher C.; Fleagle, John G.; Miller, Ellen R.; Feibel, Craig; Fox, David L.; Feinberg, Josh; Pugh, Kelsey D. (2017). "New infant cranium from the African Miocene sheds light on ape evolution" (Submitted manuscript). Nature. 548 (7666): 169–174. doi:10.1038/nature23456. PMID 28796200.

- ↑ Ryan, Timothy M.; Silcox, Mary T.; Walker, Alan; Mao, Xianyun; Begun, David R.; Benefit, Brenda R.; Gingerich, Philip D.; Köhler, Meike; Kordos, László (2012-09-07). "Evolution of locomotion in Anthropoidea: the semicircular canal evidence". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 279 (1742): 3467–3475. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.0939. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 3396915. PMID 22696520.

- ↑ Yapuncich, Gabriel S.; Seiffert, Erik R.; Boyer, Doug M. (2017-06-01). "Quantification of the position and depth of the flexor hallucis longus groove in euarchontans, with implications for the evolution of primate positional behavior". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 163 (2): 367–406. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23213. ISSN 1096-8644. PMID 28345775.

- ↑ "Amphipithecidae - Overview - Encyclopedia of Life". Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved 2017-08-12.

- ↑ "Eosimiidae - Overview - Encyclopedia of Life". Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved 2017-08-12.

- ↑ "Parapithecoidea - Overview - Encyclopedia of Life". Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved 2017-08-12.

- ↑ Marivaux, Laurent; Antoine, Pierre-Olivier; Baqri, Syed Rafiqul Hassan; Benammi, Mouloud; Chaimanee, Yaowalak; Crochet, Jean-Yves; Franceschi, Dario de; Iqbal, Nayyer; Jaeger, Jean-Jacques (2005-06-14). "Anthropoid primates from the Oligocene of Pakistan (Bugti Hills): Data on early anthropoid evolution and biogeography". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (24): 8436–8441. doi:10.1073/pnas.0503469102. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1150860. PMID 15937103.

- ↑ Hill, C. M. (2000). "Conflict of Interest Between People and Baboons: Crop Raiding in Uganda". International Journal of Primatology. 21 (2): 299–315. doi:10.1023/A:1005481605637. hdl:10919/65514.

- ↑ Siex, K. S.; Struhsaker, T. T. (1999). "Colobus monkeys and coconuts: A study of perceived human-wildlife conflicts". Journal of Applied Ecology. 36 (6): 1009–1020. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2664.1999.00455.x.

- ↑ Brennan, E. J.; Else, J. G.; Altmann, J. (1985). "Ecology and behaviour of a pest primate: Vervet monkeys in a tourist-lodge habitat". African Journal of Ecology. 23: 35–44. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1985.tb00710.x.

- ↑ Sheredos, S. J. (1991). "An evaluation of capuchin monkeys trained to help severely disabled individuals" (PDF). The Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 28 (2): 91–96. doi:10.1682/JRRD.1991.04.0091.

- ↑ "The supply and use of primates in the EU". European Biomedical Research Association. 1996. Archived from the original on 2012-01-17.

- 1 2 3 Carlsson, H. E.; Schapiro, S. J.; Farah, I.; Hau, J. (2004). "Use of primates in research: A global overview". American Journal of Primatology. 63 (4): 225–237. doi:10.1002/ajp.20054. PMID 15300710.

- 1 2 Weatherall, D., et al., (The Weatherall Committee) (2006). The use of non-human primates in research (PDF) (Report). London, UK: Academy of Medical Sciences.

- ↑ Bushnell, D. (1958). "The beginnings of research in space biology at the Air Force Missile Development Center, 1946–1952". History of Research in Space Biology and Biodynamics. NASA. Archived from the original on 2013-04-10. Retrieved 2013-04-10.

- ↑ Bonné, J. (2005-10-28). "Some bravery as a side dish". msnbc.com. Retrieved 2009-08-15.

- ↑ Institut De Recherche Pour Le Développement (2002). "Primate Bushmeat : Populations Exposed To Simian Immunodeficiency Viruses". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2009-08-15.

- ↑ Experts, Disha (2017-12-25). THE MEGA YEARBOOK 2018 - Current Affairs & General Knowledge for Competitive Exams with 52 Monthly ebook Updates & eTests - 3rd Edition. ISBN 9789387421226.

- ↑ Reddy (2006-12-01). Indian Hist (Opt). ISBN 9780070635777.

- ↑ Cooper, J. C. (1992). Symbolic and Mythological Animals. London: Aquarian Press. pp. 161–63. ISBN 978-1-85538-118-6.

- ↑ Benson, E. (1972). The Mochica: A Culture of Peru. New York: Praeger Press. ISBN 978-0-500-72001-1.

- ↑ Berrin, K. & Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera (1997). The Spirit of Ancient Peru: Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-01802-6.

- ↑ Lau, T. (2005). The Handbook of Chinese Horoscopes (5th ed.). New York: Souvenir Press. pp. 238–244. ISBN 978-0060777777.

Literature cited

- Groves, C. (2008). Extended Family: Long Lost Cousins. Conservation International. ISBN 978-1-934151-25-9. OCLC 300051037.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: monkeys |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Monkey. |

- "The Impossible Housing and Handling Conditions of Monkeys in Research Laboratories", by Viktor Reinhardt, International Primate Protection League, August 2001

- The Problem with Pet Monkeys: Reasons Monkeys Do Not Make Good Pets, an article by veterinarian Lianne McLeod on About.com

- Helping Hands: Monkey helpers for the disabled, a U.S. national non-profit organization based in Boston Massachusetts that places specially trained capuchin monkeys with people who are paralyzed or who live with other severe mobility impairments