Bedouin

Bedouin wedding procession in the Jerusalem section of the Pike at the 1904 World's Fair | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 21,250,700[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 10,199,000 | |

| 230,000[2]-2,257,000 | |

| 350,000–1,100,000 | |

| 467,000 (2013); 380,000 (2007)[3] | |

| 902,000 (2007)[4] | |

| 763,000 | |

| 620,000 (2013)[5][6] | |

| 457,000 | |

| 290,000 | |

| 189,000 | |

| 177,000 | |

| 144,000 | |

| 250,000 (2012)[7] | |

| 54,000 | |

| 50,000 | |

| 47,000 | |

| 39,000 | |

| 30,000[8] | |

| 28,000 | |

| Languages | |

| Arabic dialects (Bedawi • Hassāniyya • Hejazi • Najdi • Omani) | |

| Religion | |

| Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Arabs | |

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

|

The Bedouin or Bedu (/ˈbɛduɪn/;[9] Arabic: بَدْو badw, singular Arabic: بَدَوِي badawī) are a grouping of nomadic Arab people who have historically inhabited the desert regions in North Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq and the Levant.[10] The English word bedouin comes from the Arabic badawī, which means "desert dweller", and is traditionally contrasted with ḥāḍir, the term for sedentary people.[11] Bedouin territory stretches from the vast deserts of North Africa to the rocky sands of the Middle East.[12] They are traditionally divided into tribes, or clans (known in Arabic as ʿašāʾir; عَشَائِر), and share a common culture of herding camels and goats.[12] The vast majority of Bedouin adhere to Islam.[13]

Bedouins have been referred to by various names throughout history, including Qedarites in the Old Testament and Arabaa by the Assyrians (ar-ba-a-a being a nisba of the noun Arab, a name still used for Bedouins today). They are referred to as the ʾAʿrāb (أعراب) in the Quran.

While many Bedouins have abandoned their nomadic and tribal traditions for a modern urban lifestyle, many retain traditional Bedouin culture such as retaining the traditional ʿašāʾir clan structure, traditional music, poetry, dances (such as saas), and many other cultural practices and concepts. Urbanised Bedouins often organise cultural festivals, usually held several times a year, in which they gather with other Bedouins to partake in and learn about various Bedouin traditions—from poetry recitation and traditional sword dances to playing traditional instruments and even classes teaching traditional tent knitting. Traditions like camel riding and camping in the deserts are still popular leisure activities for urbanised Bedouins who live within close proximity to deserts or other wilderness areas.

Etymology

The term "Bedouin" derives from the singular form of the Arabic word badu (بدو), which literally means "Badiyah dwellers" in Arabic.[14] The word bādiyah (بَادِية) means visible land, in the sense of "plain" or "desert".[15] The term "Bedouin" therefore means "those in bādiyah" or "those in the desert". In English usage, however, the form "Bedouin" is commonly used for the singular term, the plural being "Bedouins", as indicated by the Oxford English Dictionary, second edition.

The term "Bedouin" also uses the same root word as the Arabic noun for "the beginning"; "بداية"; "Bedaya." Most Arabs believe the Bedouins to be the predecessors to settled Arabs, including the Nabataeans Arabs of the more westerly Levant region. According to a hadith, Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab said of the Bedouin, "[T]hey are the origin of the Arabs and the substance of Islam."[16][17] and the word for the ethnicity itself may be influenced by that.[18]

Society

A widely quoted Bedouin apothegm is "I am against my brother, my brother and I are against my cousin, my cousin and I are against the stranger"[19] sometimes quoted as "I and my brother are against my cousin, I and my cousin are against the stranger."[20] This saying signifies a hierarchy of loyalties based on the proximity of male kinship, beginning with the nuclear family through the lineage and then the paternal tribe, and, in principle at least, to an entire genetic or linguistic group (which is perceived to akin to kinship in the Middle East and North Africa generally). Disputes are settled, interests are pursued, and justice and order are dispensed and maintained by means of this framework, organized according to an ethic of self-help and collective responsibility (Andersen 14). The individual family unit (known as a tent or "gio" bayt) typically consisted traditionally of three or four adults (a married couple plus siblings or parents) and any number of children. When resources were plentiful, several tents would travel together as a goum. While these groups were sometimes linked by patriarchal lineage, others were just as likely linked by marriage alliances (new wives were especially likely to have close male relatives join them). Sometimes, the association was based on acquaintance and familiarity, or even no clearly defined relation except for simple shared membership within a tribe.

The next scale of interaction within groups was the ibn ʿamm (cousin, or literally "son of an uncle") or descent group, commonly of three to five generations. These were often linked to goums, but where a goum would generally consist of people all with the same herd type, descent groups were frequently split up over several economic activities, thus allowing a degree of 'risk management'; should one group of members of a descent group suffer economically, the other members of the descent group would be able to support them. Whilst the phrase "descent group" suggests purely a lineage-based arrangement, in reality these groups were fluid and adapted their genealogies to take in new members.

The largest scale of tribal interactions is the tribe as a whole, led by a Sheikh (Arabic: شيخ šayḫ, literally, "old man"), though the title is refer to leaders in varying contexts. The tribe often claims descent from one common ancestor—as mentioned above. The tribal level is the level that mediated between the Bedouin and the outside governments and organizations. Distinct structure of the Bedouin society leads to long lasting rivalries between different clans.

Bedouin traditionally had strong honor codes, and traditional systems of justice dispensation in Bedouin society typically revolved around such codes. The bisha'a, or ordeal by fire, is a well-known Bedouin practice of lie detection. See also: Honor codes of the Bedouin, Bedouin systems of justice. Urbanized Bedouin are less likely to continue such traditions, instead opting for the codes of behavior that govern the wider settled community to which they belong.

Traditions

Herding

Livestock and herding, principally of goats and dromedary camels comprised the traditional livelihoods of Bedouins. These two animals were used for meat, dairy products, and wool.[21] Most of the staple foods that made up the Bedouins' diet were dairy products.[21]

Camels, in particular, had numerous cultural and functional uses. Having been regarded as a "gift from God", they were the main food source and method of transportation for many Bedouins.[22] In addition to their extraordinary milking potentials under harsh desert conditions, their meat was occasionally consumed by Bedouins.[23] As a cultural tradition, camel races were organized during celebratory occasions, such as weddings or religious festivals.[24]

Oral poetry

Oral poetry was the most popular art form among Bedouins. Having a poet in one's tribe was highly regarded in society. In addition to serving as a form of art, poetry was used as a means of conveying information and social control.[25]

Raiding or ghazw

The well-regulated traditional habit of Bedouin tribes of raiding other tribes, caravans, or settlements is known in Arabic as ghazw.[26]

History

Early history

Historically, the Bedouin engaged in nomadic herding, agriculture and sometimes fishing. A major source of income was the taxation of caravans, and tributes collected from non-Bedouin settlements. They also earned income by transporting goods and people in caravans across the desert.[27] Scarcity of water and of permanent pastoral land required them to move constantly.

The Moroccan traveller, Ibn Battuta, reported that in 1326 on the route to Gaza, the Egyptian authorities had a customs post at Qatya on the north coast of Sinai. Here Bedouin were being used to guard the road and track down those trying to cross the border without permission.[28]

The Early Medieval grammarians and scholars seeking to develop a system of standardizing the contemporary Classical Arabic for maximal intelligibility across the Arabophone areas, believed that the Bedouin spoke the purest, most conservative variety of the language. To solve irregularities of pronunciation, the Bedouin were asked to recite certain poems, whereafter consensus was relied on to decide the pronunciation and spelling of a given word.[29]

Ottoman period

.jpg)

A plunder and massacre of the Hajj caravan by Bedouin tribesmen occurred in 1757, led by Qa'dan al-Fa'iz of the Bani Saqr tribe. An estimated 20,000 pilgrims were either killed in the raid or died of hunger or thirst as a result. Although Bedouin raids on Hajj caravans were fairly common, the 1757 raid represented the peak of such attacks.[30][31][32][33][34]

Under the Tanzimat reforms in 1858 a new Ottoman Land Law was issued, which offered legal grounds for the displacement of the Bedouin. As the Ottoman Empire gradually lost power, this law instituted an unprecedented land registration process that was also meant to boost the empire's tax base. Few Bedouin opted to register their lands with the Ottoman Tapu, due to lack of enforcement by the Ottomans, illiteracy, refusal to pay taxes and lack of relevance of written documentation of ownership to the Bedouin way of life at that time.[35]

At the end of the 19th century Sultan Abdülhamid II settled Muslim populations (Circassians) from the Balkan and Caucasus among areas predominantly populated by the nomads in the regions of modern Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and Palestine, and also created several permanent Bedouin settlements, although the majority of them did not remain.[36]

Ottoman authorities also initiated private acquisition of large plots of state land offered by the sultan to the absentee landowners (effendis). Numerous tenants were brought in order to cultivate the newly acquired lands. Often it came at the expense of the Bedouin lands.

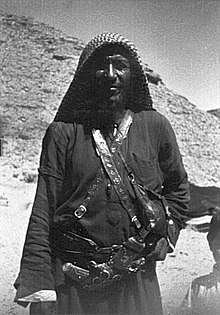

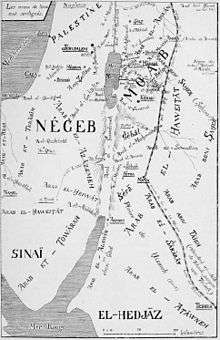

In the late 19th century, many Bedouin began transition to a semi-nomadic lifestyle. One of the factors was the influence of the Ottoman empire authorities[37] who started a forced sedentarization of the Bedouin living on its territory. The Ottoman authorities viewed the Bedouin as a threat to the state's control and worked hard on establishing law and order in the Negev.[36] During World War I, the Negev Bedouin fought with the Turks against the British, but later, under T. E. Lawrence's assist, the Bedouins switched side and fought the Turks. Hamad Pasha al-Sufi (died 1923), Sheikh of the Nijmat sub-tribe of the Tarabin, led a force of 1,500 men who joined the Turkish offensive against the Suez Canal.[38]

In Orientalist historiography, the Negev Bedouin have been described as remaining largely unaffected by changes in the outside world until recently. Their society was often considered a "world without time."[39] Recent scholars have challenged the notion of the Bedouin as 'fossilized,' or 'stagnant' reflections of an unchanging desert culture. Emanuel Marx has shown that Bedouin were engaged in a constantly dynamic reciprocal relation with urban centers.[40] Bedouin scholar Michael Meeker explains that "the city was to be found in their midst."[41]

In the 20th century

In the 1950s and 1960s large numbers of Bedouin throughout Midwest Asia started to leave the traditional, nomadic life to settle in the cities of Midwest Asia, especially as hot ranges have shrunk and populations have grown. For example, in Syria, the Bedouin way of life effectively ended during a severe drought from 1958 to 1961, which forced many Bedouin to abandon herding for standard jobs.[42][43] Similarly, governmental policies in Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Iraq, Tunisia, oil-producing Arab states of the Persian Gulf and Libya,[44][45] as well as a desire for improved standards of living, effectively led most Bedouin to become settled citizens of various nations, rather than stateless nomadic herders.

Governmental policies pressing the Bedouin have in some cases been executed in an attempt to provide service (schools, health care, law enforcement and so on—see Chatty 1986 for examples), but in others have been based on the desire to seize land traditionally roved and controlled by the Bedouin. In recent years, some Bedouin have adopted the pastime of raising and breeding white doves,[46] while others have rejuvenated the traditional practice of falconry.[47][48]

In different countries

Arabian Peninsula

Saudi Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula is the original home of the Bedouin. From here they started to spread out to surrounding deserts, forced out by the lack of water and food. According to tradition, the Saudi Bedouin are descendants of two groups. One group, the Yemenis, settled in the Southwestern Arabia, in the mountains of Yemen, and claim they descend from a semi-legendary ancestral figure, Qahtan (or Joktan). The second group, the Qaysis, settled in North-Central Arabia and claimed they were descendants of the Biblical Ishmael.[49]

A number of additional Bedouin tribes reside in Saudi Arabia. Among them are the, Anazzah, Bani Tameem, Jihnan, Shammar, al-Murrah, Qara, Mahra, Harasis, Dawasir, Harb, Ghamid, Mutayr, Subaie, 'Utayba, Bani khalid, Qahtan, Rashaida, Ansar and Yam. In Arabia and the adjacent deserts there are around 100 large tribes of 1,000 members or more. Some tribes number up to 20,000 and a few of the larger tribes may have up to 100,000 members. Inside Saudi Arabia the Bedouin remained the majority of the population during the first half of the 20th century. However, due to change of lifestyle their number has decreased dramatically.

According to Ali Al-Naimi, the Bedouin, or Bedu, would travel in family and tribal groups, across the Arabian Peninsula in groups of fifty to a hundred. A clan was composed of a number of families, while a number of clans formed a tribe. Tribes would have areas reserved for their livestock called dirahs, which included wells for their exclusive use. They lived in black goat-hair tents called bayt al-shar, divided by cloth curtains into rug-floor areas for males, family and cooking. In Hofuf, they bartered their sheep, goats and camels, including milk and wool, for grain and other staples. Al-Naimi also quotes Paul Harrison's observation of the Bedouin, "There seems to be no limit at all to their endurance."[50]

Levant

Syria

Although the Arabian desert was the homeland of the Bedouin, some groups have migrated to the north. It was one of the first lands inhabited by the Bedouin outside the Arabian desert.[51] Today there are over a million Bedouin living in Syria, making a living herding sheep and goats.[52] The largest Bedouin clan in Syria is called Ruwallah who are part of the 'Anizzah' tribe. Another famous branch of the Anizzah tribe is the two distinct groups of Hasana and S'baa who largely arrived from the Arabian peninsula in the 18th century.[53]

Herding among the Bedouin was common until the late 1950s, when it effectively ended during a severe drought from 1958 to 1961. Due to the drought, many Bedouin were forced to give up herding for standard jobs.[54] Another factor was the formal annulling of the Bedouin tribes' legal status in Syrian law in 1958, along with attempts of the ruling Ba'ath Party regime to wipe out tribalism. Preferences for customary law (‘urf) in contrast to state law (qanun) have been informally acknowledged and tolerated by the state in order to avoid having its authority tested in the tribal territories.[55] In 1982 the al-Assad family turned to the Bedouin tribe leaders for assistance during the Muslim Brotherhood uprising against al-Assad government (see 1982 Hama massacre). The Bedouin sheikhs' decision to support Hafez al-Assad led to a change in attitude on the part of the government that permitted the Bedouin leadership to manage and transform critical state development efforts supporting their own status, customs and leadership.

As a result of the Syrian Civil War some Bedouins became refugees and found shelter in Jordan,[56] Turkey, Lebanon, and other states.

Israel and Palestine

Prior to the 1948 Israeli Declaration of Independence, an estimated 65,000–90,000 Bedouins lived in the Negev desert. According to Encyclopedia Judaica, 15,000 Bedouin remained in the Negev after 1948; other sources put the number as low as 11,000.[57] Another source states that in 1999 110,000 Bedouins lived in the Negev, 50,000 in the Galilee and 10,000 in the central region of Israel.[58] All of the Bedouins residing in Israel were granted Israeli citizenship in 1954.[59]

The Bedouin who remained in the Negev belonged to the Tiaha confederation[60] as well as some smaller groups such as the 'Azazme and the Jahalin. After 1948, some Negev Bedouins were displaced. The Jahalin tribe, for instance, lived in the Tel Arad region of the Negev prior to the 1950s. In the early 1950s, the Jahalin were among the tribes that, according to Emmanuel Marks, "moved or were removed by the military government".[61] They ended up in the so-called E1 area East of Jerusalem.

About 1,600 Bedouin serve as volunteers in the Israel Defense Forces, many as trackers in the IDF's elite tracking units.[62]

Famously, Bedouin shepherds were the first to discover the Dead Sea Scrolls, a collection of Jewish texts from antiquity, in the Judean caves of Qumran in 1946. Of great religious, cultural, historical and linguistic significance, 972 texts were found over the following decade, many of which were discovered by Bedouins.

Successive Israeli administrations tried to demolish Bedouins villages in the Negev. Between 1967 and 1989, Israel built seven legal townships in the north-east of the Negev, with Tel as-Sabi or Tel Sheva the first. The largest, city of Rahat, has a population of over 58,700 (as of December 2013);[63] as such it is the largest Bedouin settlement in the world. Another well-known township out of the seven of them that the Israeli government built, is Hura. According to the Israel Land Administration (2007), some 60 per cent of the Negev Bedouin live in urban areas.[64] The rest live in so-called unrecognized villages, which are not officially recognized by the state due to general planning issues and other political reasons. They were built chaotically without taking into consideration local infrastructure. These communities are scattered all over the Northern Negev and often are situated in inappropriate places, such as military fire zones, natural reserves, landfills, etc.

On 29 September 2003, Israeli government adapted a new "Abu Basma Plan" (Resolution 881), according to which a new regional council was formed, unifying a number of unrecognized Bedouin settlements—Abu Basma Regional Council.[65] This resolution also regarded the need to establish seven new Bedouin settlements in the Negev,[66] literally meaning the official recognition of unrecognized settlements, providing them with a municipal status and consequently with all the basic services and infrastructure. The council was established by the Interior Ministry on 28 January 2004.[67]

Israel is currently building or enlarging some 13 towns and cities in the Negev. According to the general planning, all of them will be fully equipped with the relevant infrastructure: schools, medical clinics, postal offices, etc. and they also will have electricity, running water and waste control. Several new industrial zones meant to fight unemployment are planned, some are already being constructed, like Idan haNegev in the suburbs of Rahat.[68] It will have a hospital and a new campus inside.[69] The Bedouins of Israel receive free education and medical services from the state. They are allotted child cash benefits, which has contributed to the high birthrate among the Bedouin (5% growth per year). But unemployment rate remains very high, and few obtain a high school degree (4%), and even fewer graduate from university (0.6%).[70]

In September 2011, the Israeli government approved a five-year economic development plan called the Prawer plan.[71] One of its implications is a relocation of some 30.000-40.000 Negev Bedouin from areas not recognized by the government to government-approved townships.[72][73] In a 2012 resolution the European Parliament called for the withdrawal of the Prawer plan and respect for the rights of the Bedouin people.[74] In September 2014, Yair Shamir, who heads the Israeli government's ministerial committee on Bedouin resettlement arrangements, stated that the government was examining ways to lower the birthrate of the Bedouin community in order to improve its standard of living. Shamir claimed that without intervention, the Bedouin population could exceed half a million by 2035.[75][76]

Jordan

Most of the Bedouin tribes migrated from the Arabian Peninsula to what is Jordan today between the 14th and 18th centuries.[77] Today Bedouins make up from 33%[78] to 40%[79] of the population of Jordan. Often they are referred to as a backbone of the Kingdom,[78][80] since Bedouin clans traditionally support the monarchy.[81]

Most of Jordan's Bedouin live in the vast wasteland that extends east from the Desert Highway.[82] The eastern Bedouin are camel breeders and herders, while the western Bedouin herd sheep and goats. Some Bedouin in Jordan are semi-nomads, they adopt a nomadic existence during part of the year but return to their lands and homes in time to practice agriculture.

The largest nomadic groups of Jordan are the Banū (Banī laith; they reside in Petra), baniṢakhr and Banū al-Ḥuwayṭāt (they reside in Wadi Rum. There are numerous lesser groups, such as the al-Sirḥān, Banū Khālid, Hawazim, ʿAṭiyyah, and Sharafāt. The Ruwālah (Rwala) tribe, which is not indigenous, passes through Jordan in its yearly wandering from Syria to Saudi Arabia.[83]

The Jordanian government provides the Bedouin with different services such as education, housing and health clinics. However, some Bedouins give it up and prefer their traditional nomadic lifestyle.

In the recent years there is a growing discontent of the Bedouin with the ruling monarch, but the king manages to deal with it. In August 2007, police clashed with some 200 Bedouins who were blocking the main highway between Amman and the port of Aqaba. Livestock herders, they were protesting the government's lack of support in the face of the steeply rising cost of animal feed, and expressed resentment about government assistance to refugees.[78]

Arab Spring events in 2011 led to demonstrations in Jordan, and Bedouins took part in them. But it is unlikely that the Hashemites are to expect a revolt similar to turbulence in other Arab states. The main reasons for that are the high respect to the monarch, and contradictory interests of different groups of the Jordanian society. The King Abdullah II maintains his distance from the complaints by allowing blame to fall on government ministers, whom he replaces at will.[84]

North Africa

Maghreb

In the 11th century, reigning over Ifriqiya, the Zirids somehow recognised the sovereignty of the caliph of Cairo. Probably in 1048, the ruler or viceroy Zirid, al-Mu'izz, decided to stop this sovereignty. The Fatimids were then powerless to lead a punitive expedition.

In the 11th century, the Bedouin tribes of Banu Hilal and Banu Sulaym, who originated from Syria and North Arabia respectively,[85] living at the time in a desert between the Nile and the Red Sea, moved westward into the Maghreb areas and were joined by a third Bedouin tribe of Maqil, which had its roots in South Arabia.[85] The vizier of the caliph of Cairo chose to let go of the Maghreb and obtained the agreement of his sovereign. They set off with women, children, camping equipment, some stopping on the way, especially in Cyrenaica, where they are still one of the essential elements of the settlement, but most arrived in Ifriqiya by the Gabes region; Berber armies were defeated in trying to protect the walls of Kairouan.

The Zirids abandoned Kairouan to take refuge on the coast where they survived for a century. Ifriqiya, the Banu Hilal and Banu Sulaym spread is on the high plains of Constantine where they gradually choked the Qal'a of Banu Hammad, as they had done Kairouan few decades ago. From there, they gradually gained the upper Algiers and Oran plains, some were taken to the Moulouya valley and in Doukkala plains by the Caliph of Marrakesh in the second half of the 12th century.

In the 13th century, they lived in all the Maghreb plains with the exception of the main mountain ranges and some coastal regions that served as refuges for the natives. They gave up their old trade breeder of camels to look after the care of the sheep and oxen.

Ibn Khaldun, a Muslim historian writes: "Similar to an army of locusts, they destroy everything in their path."[86]

The Bedouin dialects are used in Maghrebi regions of Morocco Atlantic Coast, in regions of High Plains and Sahara in Algeria, in regions of Tunisian Sahel and in regions of Tripolitania. The Bedouin dialects has four major varieties:[87][88]

- Sulaym dialects, Libya and southern Tunisia;

- Eastern Hilal dialects, central Tunisia and eastern Algeria;

- Central Hilal dialects, south and central Algeria, especially in border areas of Sahara;

- Maqil dialects, western Algeria and Morocco;

In Morocco, Bedouin Arabic dialects are spoken in plains and in recently founded cities such as Casablanca. Thus, the city Arabic dialect shares with the Bedouin dialects gal 'to say' (qala); they also represent the bulk of modern urban dialects (Koinés), such as those of Oran and Algiers.[89]

Egypt

Bedouins in Egypt mostly reside in the Sinai peninsula and in the suburbs of the Egyptian capital of Cairo.[90] The past few decades have been difficult for traditional Bedouin culture due to changing surroundings and the establishment of new resort towns on the Red Sea coast, such as Sharm el-Sheikh. Bedouins in Egypt are facing a number of challenges: erosion of traditional values, unemployment, and various land issues. With urbanization and new education opportunities, Bedouins started to marry outside their tribe, a practice that once was completely inappropriate.[90]

Bedouins living in the Sinai peninsula did not benefit much from employment in the initial construction boom due to low wages offered. Sudanese and Egyptians workers were brought here as construction laborers instead. When the tourist industry started to bloom, local Bedouins increasingly moved into new service positions such as cab drivers, tour guides, campgrounds or cafe managers. However, the competition is very high, and many Sinai Bedouins are unemployed. Since there are not enough employment opportunities, Tarabin Bedouins as well as other Bedouin tribes living along the border between Egypt and Israel are involved in inter-border smuggling of drugs and weapons,[90] as well as infiltration of prostitutes and African labor workers.

In most countries in the Middle East the Bedouin have no land rights, only users' privileges,[91] and it is especially true for Egypt. Since the mid-1980s, the Bedouins who held desirable coastal property have lost control of much of their land as it was sold by the Egyptian government to hotel operators. The Egyptian government did not see the land as belonging to Bedouin tribes, but rather as a state property.

In the summer of 1999, the latest dispossession of land took place when the army bulldozed Bedouin-run tourist campgrounds north of Nuweiba as part of the final phase of hotel development in the sector, overseen by the Tourist Development Agency (TDA). The director of the Tourist Development Agency dismissed Bedouin rights to most of the land, saying that they had not lived on the coast prior to 1982. Their traditional semi-nomadic culture has left Bedouins vulnerable to such claims.[92]

The Egyptian Revolution of 2011 brought more freedom to the Sinai Bedouin, but since it was deeply involved in weapon smuggling into Gaza after a number of terror attacks on the Egypt-Israel border a new Egyptian government has started a military operation in Sinai in the summer-fall of 2012. Egyptian army has demolished over 120 underground tunnels leading from Egypt to Gaza that were used as smuggling channels and gave profit to the Bedouin families on the Egyptian side, as well as the Palestinian clans on the other side of the border. Thus the army has delivered a threatening message to local Bedouin, compelling them to cooperate with state troops and officials. After negotiations the military campaign ended up with a new agreement between the Bedouin and Egyptian authorities.[93]

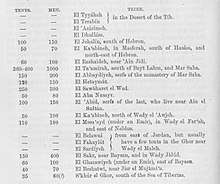

Tribes and populations

There are a number of Bedouin tribes, but the total population is often difficult to determine, especially as many Bedouin have ceased to lead nomadic or semi-nomadic lifestyles. Below is a partial list of Bedouin tribes and their historic place of origin.

- The Harb tribe is a tribe in Saudi Arabia and Yemen on the Arabian Peninsula.

- Banu Hilal,[94] some tribes of this confederation are Bedouin, they live in western Morocco, central Algeria, southern Tunisia and Eastern Desert and others steppe of the region.

- Banu Sulaym,[94] Big tribes, the Sulaym in the east (Libya and southern Tunisia),[95] present in Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco and Syria.[95][96]

- `Anizzah, some tribes of this confederation are Bedouin, they live in Northern Saudi Arabia, Western Iraq, the Persian Gulf states, Syrian steppe and in Bekaa.

- 'Azazme, Negev desert and Egypt.

- Beni Hamida, east of Dead Sea, Jordan.

- Bani Tameem in Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Qatar, Jordan, United Arab Emirates Bahrain and Kuwait.

- Banu Yam centered in Najran Province, Saudi Arabia and Iraq

- Beni Sakhr in Egypt Iraq, Syria and Jordan.

- Dulaim, a very large and powerful tribe in Al Anbar, Western Iraq.

- al-Duwasir, south of Riyadh.

- Ghamid, large tribe from Al-Bahah Province, Saudi Arabia, mostly settled, but with a small Bedouin section known as Badiyat Ghamid.

- al-Hadid, large Bedouin tribe found in Iraq, Syria and Jordan. Now mostly are settled in cities such as Haditha in Iraq, Homs & Hama in Syria, and Amman in Jordan.

- al-Howeitat, one of the largest tribes in Jordan (al-Hesa).

- al-Jaloudi (al-Jaludi) of al-Harb ("Goliath's Tribe" of "War Tribe"), one of the largest tribes in the Arabian Peninsula, mostly settled in Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Palestine, Syria and Iraq. The tribe has deep roots in the Umayyad and Abbassid dynasties.

- al-Khassawneh, one of the largest tribes in Northern Irbid Jordan and well known for the long history dominating the North.

- Bani Khalid one of the Bedouin tribes in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, Jordan, Egypt and Syria.

- al-Majali South Jordan Majalis have long dominated Karak Bedouin society, Strongest tribe in Karak, one of the largest political power in Jordan

- al-Mawasi, a group living on the central Gaza Strip coast.

- Muzziena tribe in Dahab and South Sinai (Egypt).

- Shahran (al-Ariydhah), a very large tribe residing in the area between Bisha, Khamis Mushait and Abha. Al-Arydhah 'wide' is a famous name for Shahran because it has a very large area, in Saudi Arabia.

- Shammar, a very large and influential tribe in Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Jordan. Descended from the ancient tribe of Tayy from Najd.

- Subay', central Nejd.

- Tarabin—one of the largest tribes in Egypt (Sinai) and Israel (Negev).

- Tuba-Zangariyye, Israel near the Jordan river cliff in the Eastern Galilee.

- Al Wahiba, a large tribe in Oman residing in the Sharqiya Sands, also known as the Wahiba Sands

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ Losleben, Elizabeth (2003). The Bedouin of the Middle East. Lerner Publications. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-8225-0663-8. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ↑ Algeria-Watch. "Selon le dernier recensement: L'Algérie compte 34,8 millions d'habitants". Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ "Social characteristics for Badia". The Hashemite Fund for Development of Jordan Badia. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ↑ Morrow, Adam (18 June 2007). "Bedouin Take on the Govt". Inter Press Service. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ Ben Solomon, Ariel (14 January 2013). "Saudi Arabia to aid Jordan with Syrian refugees". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ "KSA sets up 5,000 tents for Syrian refugees". Arab News. 6 August 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ Sales, Ben (20 August 2012). "Despite hardships, some Bedouins still feel obligation to serve Israel". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ Naylor, Hugh. "Israel plans to move West Bank Bedouin". The National. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ "Bedouin". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ↑ Dostal, Walter (1967). Die Beduinen in Südarabien. Verlag Ferdinand Berger & Söhne.

- ↑ Pietruschka, Ute (2006). "Bedouin". In McAuliffe, Jane Dammen. Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān. Brill. (Subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 Malcolm, Peter; Losleben, Elizabeth (2004). Libya. Marshall Cavendish. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-7614-1702-6. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ "Bedouin Life". Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ↑ "Nomad". Google Translate. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ Sidebotham, Steven E.; Hense, Martin; Nouwens, Hendrikje M. (2008). The Red Land: The Illustrated Archaeology of Egypt's Eastern Desert. American University in Cairo Press. p. 257. ISBN 978-977-416-094-3. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ↑ Sahih al-Bukhari, Vol. 4, p. 206.

- ↑ Duri, A. A. (2012). The Historical Formation of the Arab Nation (RLE: the Arab Nation). Routledge. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-415-62286-8.

- ↑ Hitti, Philip K. (1996). "The Original Arab, The Bedouin". The Arabs: A Short History. Regnery Publishing. Archived from the original on 10 November 2000. Retrieved 19 October 2015 – via OneWorld Magazine: Deserts.

- ↑ Marx, Emanuel. "Ecology and politics of Middle Eastern politics". In Weissleder, Wolfgang. The Nomadic alternative: Modes and models of interaction in the African-Asian deserts and steppes. Moulton. p. 59. ISBN 978-0202900537. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ↑ Naguib, Nefissa (2009). Women, Water and Memory: Recasting Lives in Palestine. Brill. p. 79. ISBN 978-9004167780. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- 1 2 Abu-Saad, K.; Weitzman, S.; Abu-Rabiah, Y.; Abu-Shareb, H. & Fraser, D. "Rapid lifestyle, diet and health changes among urban Bedouin Arabs of southern Israel". Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ Breulmann, Marc; Böer, Benno; Wernery, Ulrich; Wernery, Renate; El Shaer, Hassan; Alhadrami, Ghaleb; Gallacher, David; Peacock, John; Chaudhary, Shaukat Ali; Brown, Gary & Norton, John. "The Camel From Tradition to Modern Times" (PDF). UNESCO. Retrieved 31 July 2015. :10

- ↑ The Camel From Tradition to Modern Times.:21–24

- ↑ The Camel From Tradition to Modern Times.:25

- ↑ Meisami, Julie Scott; Starkey, Paul. Encyclopedia of Arabic Literature. Routledge. p. 147. ISBN 978-0415571135.

- ↑ Eveline van der Steen, Near Eastern Tribal Societies During the Nineteenth Century: Economy, Society and Politics Between Tent and Town, chapter "Raiding and robbing". Routledge, 2014

- ↑ Beckerleg, Susan. "Hidden History, Secret Present: The Origins and Status of African Palestinians". London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Translated by Salah Al Zaroo.

- ↑ Ibn Battuta (1929). Travels in Asia and Africa. 1325–1354. Delhi 110052: Low Price Publications. p. 54. ISBN 81-7536-174-3. Translated and selected by H.A.R. Gibb.

- ↑ Holes, Clive (2004). Modern Arabic: Structures, Functions and Varieties (Revised ed.). Washington DC: Georgetown University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-58901-022-2.

- ↑ Cohen, Amnon (1973). Palestine in the 18th century: Patterns of Government and Administration. Magnes Press. p. 20.

- ↑ Abu-Rabia, Aref (2001). A Bedouin Century: Education and Development Among the Negev Tribes in the 20th Century. Berghahn Books. ISBN 9781571818324.

- ↑ Burns, Ross (2005). Damascus: A History. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-27105-3.

- ↑ Al-Damurdashi, Ahmad D. (1991). Abd al-Wahhāb Bakr Muḥammad, ed. Al-Damurdashi's Chronicle of Egypt, 1688–1755. BRILL. ISBN 9789004094086.

- ↑ Joudah, Ahmad Hasan (1987). Revolt in Palestine in the Eighteenth Century: The Era of Shaykh Zahir Al-ʻUmar. Kingston Press. ISBN 9780940670112.

- ↑ Shafir, Gershon (1989). Land, Labor and the Origins of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict 1882–1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52135-300-7.

- 1 2 Frantzman, Seth J.; Kark, Ruth (2011). "Bedouin Settlement in Late Ottoman and British Mandatory Palestine: Influence on the Cultural and Environmental Landscape, 1870–1948". New Middle Eastern Studies. British Society of Middle East Studies (1).

- ↑ Magness, Jodi (2003). The Archaeology of the Early Islamic Settlement in Palestine. Eisenbrauns. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-57506-070-5.

- ↑ Hillelson, S. (October 1937). "Notes on the Bedouin Tribes of Beersheba District". Palestine Exploration Quarterly. Palestine Exploration Fund. 69 (4): 242–252. doi:10.1179/peq.1937.69.4.242.

- ↑ Goering, Kurt (Autumn 1979). "Israel and the Bedouin of the Negev". Journal of Palestine Studies. 9 (1): 3–20. doi:10.1525/jps.1979.9.1.00p0173n.

- ↑ Marx, Emanuel (2005). "Nomads and Cities: The Development of a Conception". In Leder, S.; Streck, B. Shifts and Drifts in Nomad-Sedentary Relations. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag. pp. 3–16. ISBN 3-89500-413-8.

- ↑ Heidemann, Stefan (2005). "Arab Nomads and Seljuq Military". In Leder, S.; Streck, B. Shifts and Drifts in Nomad-Sedentary Relations. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag. pp. 289–306. ISBN 3-89500-413-8.

- ↑ Etheredge, Laura (2011). Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-61530-329-8.

- ↑ Leybourne, Marina; Jaubert, Ronald; Tutwiler, Richard N. (June 1993). "Changes in Migration and Feeding Patterns Among Semi-nomadic pastoralists in Northern Syria" (PDF). Overseas Development Institute.

- ↑ Peters, Emrys L. (1990). The Bedouin of Cyrenaica: Studies in Personal and Corporate Power. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-38561-9. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ Cole, Donald Powell; Altorki, Soraya (1998). Bedouin, Settlers, and Holiday-makers: Egypt's Changing Northwest Coast. American University in Cairo Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-977-424-484-1. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ Peart, Natalie. "Bedouin hospitality & the beauty of the White Desert". Part of this World. Archived from the original on 4 August 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ "Falconry". sheikhmohammed.com. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ "Falconry in the desert". Chicago Tribune. Reuters. 22 May 2013. Archived from the original on 14 May 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ "Bedouins. Origins and history". Archived from the original on 23 December 2004.

- ↑ Al-Naimi, Ali (2016). Out of the Desert. Great Britain: Portfolio Penguin. pp. 5–7. ISBN 9780241279250.

- ↑ "Arab, Najdi Bedouin in Syria". Joshua Project. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ "The Unreached Peoples Prayer Profiles". kcm.co.kr. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ↑ Buessow, Johann (2008). "Bedouin Syria: 'Anaza groups between empire and nation state, 1800–1960'". Orient Institut Beirut. Archived from the original on 24 May 2013.

- ↑ "Indigenous Peoples of the World: The Bedouin". Intercontinental Cry. Archived from the original on 15 April 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ Chatty, Dawn (2010). "The Bedouin in Contemporary Syria: The Persistence of Tribal Authority and Control" (PDF). The Middle East Journal. Middle East Institute. 64 (1). doi:10.3751/64.1.12.

- ↑ El Shamayleh, Nisreen (10 March 2012). "Syrian Bedouin find shelter in Jordan". Al Jazeera.

- ↑ Khalidi, Walid, ed. (1992). All That Remains. The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington, DC: Institute for Palestine Studies. p. 582. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- ↑ "The Bedouin in Israel: Demography". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 1 July 1999. Archived from the original on 26 October 2007.

- ↑ "Report of the Commission to Propose a Policy for Arranging Bedouin Settlement in the Negev (a.k.a. the Goldberg Report)" (PDF). Ministry of Construction (in Hebrew). pp. 6–13.

- ↑ Lustick, Ian (1980). Arabs in the Jewish State. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. pp. 57, 134–6.

- ↑ Marks, Emmanuel (1974). Bedouin Society in the Negev (in Hebrew). Tel Aviv: Rashafim. p. 17.

- ↑ "Muslim Arab Bedouins serve as Jewish state's gatekeepers". Al Arabiya English. 24 April 2013.

- ↑ "Population and Density per Sq. Km. In Localities Numbering 5,000 Residents and More on 31 XII 2013(1)" (PDF). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics.

- ↑ "Bedouin of the Negev" (PDF). Israel Land Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2011.

- ↑ "Beduin in Limbo". The Jerusalem Post. 24 December 2007. Archived from the original on 6 July 2013.

- ↑ "Government resolutions passed in recent years regarding the Arab population of Israel". Abraham Fund Initiative. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012.

- ↑ "The Bedouin Population in Transition: Site Visit to Abu Basma Regional Council". Myers-JDC-Brookdale Institute. 28 June 2005. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- ↑ "A Lіѕt of Trаvеl Tips to Make Yоur Vacation Plаnnіng Easier". bns-en.com. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ↑ Eichner, Itamar (1 April 2012). "Harvard University makes aliyah". Ynetnews.

- ↑ "Arab, Bedouin in Saudi Arabia". Joshua Project. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ "Cabinet Approves Plan to Provide for the Status of Communities in, and the Economic Development of, the Bedouin Sector in the Negev". Prime Minister's Office. 11 September 2012.

- ↑ "Bedouin transfer plan shows Israel's racism". Al Jazeera. 13 September 2011.

- ↑ Sherwood, Harriet (3 November 2011). "Bedouin's plight: "We want to maintain our traditions. But it's a dream here"". The Guardian.

- ↑ Khoury, Jack (8 July 2013). "European Parliament condemns Israel's policy toward Bedouin population". Haaretz.

The European Parliament Calls for the protection of the Bedouin communities of the West Bank and in the Negev, and for Israeli authorities to respect their rights and condemns any violations (e.g., house demolitions, forced displacements, and public service limitations). It calls also, in this context, for the withdrawal of the Prawer Plan by the Israeli Government.

- ↑ "Minister: Israel Looking at Ways to Lower Bedouin Birthrate". Haaretz. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ "To up Bedouin living standards, minister tackles birth rate". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ "Bedouin Culture in Jordan". Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - Jordan : Overview. Peoples, UNHCR report, 2007

- ↑ Daniel Noll. "Life Lessons We Learned from Jordan's Bedouins". Uncornered Market. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ "Brenda's Jordan". Archived from the original on 1 November 2015. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ "Jordan profile - Leaders". BBC News. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ "The People of Jordan". kinghussein.gov.jo. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ "Jordan". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ↑ Bronner, Ethan (4 February 2011). "Jordan Faces a Rising Tide of Unrest, but Few Expect a Revolt". The New York Times.

- 1 2 Versteegh, Kees (31 May 2014). "The Arabic Language". Edinburgh University Press. Retrieved 20 July 2017 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Decret, François (September 2003). "Les invasions hilaliennes en Ifrîqiya". www.clio.fr (in French). Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ↑ Versteegh, Kees. "Dialects of Arabic: Maghreb Dialects". TeachMideast.org.

- ↑ Barkat, Mélissa (2000). "Les dialectes Maghrébins". Détermination d'indices acoustiques robustes pour l'identification automatique des parlers arabes. Université Lumière Lyon 2.

- ↑ Versteegh, Kees (31 May 2014). "The Arabic Language". Edinburgh University Press. Retrieved 20 July 2017 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 3 Elyan, Tamim (20 August 2010). "Metropolitan Bedouins: Tarabin tribe living in Cairo between urbanization and Bedouin traditions". Daily News Egypt.

- ↑ Ben-David, Yosef (1 July 1999). "The Bedouin in Israel". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

- ↑ Abercron, Konstantin. "Sinai Beduines". allsinai.info. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ "Egypt Halts Sinai Anti-terror Campaign, Will Open Talks With Bedouin". Haaretz. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- 1 2 Versteegh, Kees (31 May 2014). The Arabic Language. Edinburgh University Press. p. 288. ISBN 978-0-7486-9460-0. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- 1 2 Versteegh, Kees (31 May 2014). The Arabic Language. Edinburgh University Press. p. 288. ISBN 978-0-7486-9460-0. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ "Le site de la tribu des Chaâmba Algériens". chaamba.net (in French).

Further reading

- Asher, Michael Last of the Bedu Penguin Books 1996

- Brous, Devorah. "The 'Uprooting:' Education Void of Indigenous 'Location-Specific' Knowledge, Among Negev Bedouin Arabs in Southern Israel". International Perspectives on Indigenous Education. (Ben Gurion University 2004)

- Chatty, D Mobile Pastoralists 1996. Broad introduction to the topic, specific focus on women's issues.

- Chatty, Dawn. From Camel to Truck. The Bedouin in the Modern World. New York: Vantage Press. 1986

- Cole, Donald P. "Where have the Bedouin gone?" Anthropological Quarterly. Washington: Spring 2003.Vol.76, Iss. 2; pg. 235

- Falah, Ghazi. "Israeli State Policy Towards Bedouin Sedentarization in the Negev", Journal of Palestine Studies, 1989 Vol. XVIII, No. 2, pp. 71–91

- Falah, Ghazi. "The Spatial Pattern of Bedouin Sedentarization in Israel", GeoJournal, 1985 Vol. 11, No. 4, pp. 361–368.

- Gardner, Andrew. "The Political Ecology of Bedouin Nomadism in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia". In Political Ecology Across Spaces, Scales and Social Groups, Lisa Gezon and Susan Paulson, eds. Rutgers: Rutgers University Press.

- Gardner, Andrew. "The New Calculus of Bedouin Pastoral Nomadism in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia". Human Organization 62 (3): 267–276.

- Gardner, Andrew and Timothy Finan. "Navigating Modernization: Bedouin Pastoralism and Climate Information in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia". MIT Electronic Journal of Middle East Studies 4 (Spring): 59–72.

- Gardner, Ann. "At Home in South Sinai." Nomadic Peoples 2000.Vol.4, Iss. 2; pp. 48–67. Detailed account of Bedouin women.

- Jarvis, Claude Scudamore. Yesterday and To-day in Sinai. Edinburgh/London: W. Blackwood & Sons; Three Deserts. London: John Murray, 1936; Desert and Delta. London: John Murray, 1938. Sympathetic accounts by a colonial administrator in Sinai.

- Lancaster, William. The Rwala Bedouin Today 1981 (Second Edition 1997). Detailed examination of social structures.

- S. Leder/B. Streck (ed.): Shifts and Drifts in Nomad-Sedentary Relations. Nomaden und Sesshafte 2 (Wiesbaden 2005)

- Lithwick, Harvey. "An Urban Development Strategy for the Negev's Bedouin Community". Center for Bedouin Studies and Development and Negev Center for Regional Development, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, August 2000

- Mohsen, Safia K. The quest for order among Awlad Ali of the Western Desert of Egypt.

- Thesiger, Wilfred (1959). Arabian Sands. ISBN 0-14-009514-4 (Penguin paperback). British adventurer lives as and with the Bedu of the Empty Quarter for 5 years

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bedouins. |

| Wikisource has the text of The New Student's Reference Work article Bedouins. |