Five Pillars of Islam

Aqidah |

|---|

|

|

Including: 1Jahmi; 2Karramiyya; 3Alawites & Qizilbash 4Sevener-Qarmatians, Assassins & Druzes 5Ajardi, Azariqa, Bayhasiyya, Najdat & Sūfrī 6Nūkkārī; 7Bahshamiyya & Ikhshîdiyya 8Alevism, Bektashi Order & Qalandariyya |

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

|

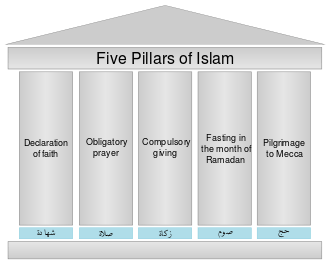

The Five Pillars of Islam (arkān al-Islām أركان الإسلام; also arkān al-dīn أركان الدين "pillars of the religion") are five basic acts in Islam, considered mandatory by believers and are the foundation of Muslim life. They are summarized in the famous hadith of Gabriel.[1][2][3][4]

The Shia, Ahmadiyya, and Sunni agree on the essential details for the performance and practice of these acts,[5][2] but the Shia do not refer to them by the same name (see Ancillaries of the Faith, for the Twelvers, and Seven pillars of Ismailism). They make up Muslim life, prayer, concern for the needy, self-purification, and the pilgrimage,[6][7] if one is able.[8]

Pillars of Sunni Islam

Shahada: Faith

Shahada is a declaration of faith and trust that professes that there is only one God (Allah) and that Muhammad is God's messenger.[9] It is a set statement normally recited in Arabic: lā ʾilāha ʾillā-llāhu muḥammadun rasūlu-llāh (لَا إِلٰهَ إِلَّا الله مُحَمَّدٌ رَسُولُ الله) "There is no god but God (and) Muhammad is the messenger of God." It is essential to utter it to become a Muslim and to convert to Islam.[10]

Salah: Prayer

Salah (ṣalāh) is the Islamic prayer. Salah consists of five daily prayers according to the Sunna; the names are according to the prayer times: Fajr (dawn), Dhuhr (noon), ʿAṣr (afternoon), Maghrib (evening), and ʿIshāʾ (night). The Fajr prayer is performed before sunrise, Dhuhr is performed in the midday after the sun has surpassed its highest point, Asr is the evening prayer before sunset, Maghrib is the evening prayer after sunset and Isha is the night prayer. All of these prayers are recited while facing in the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca and form an important aspect of the Muslim Ummah. Muslims must wash before prayer; this washing is called wudu ("purification"). The prayer is accompanied by a series of set positions including; bowing with hands on knees, standing, prostrating and sitting in a special position (not on the heels, nor on the buttocks). A Muslim may perform their prayer anywhere, such as in offices, universities, and fields. However, the mosque is the more preferable place for prayers because the mosque allows for fellowship.

Zakāt: Charity

Zakāt or alms-giving is the practice of charitable giving based on accumulated wealth. The word zakāt can be defined as purification and growth because it allows an individual to achieve balance and encourages new growth. The principle of knowing that all things belong to God is essential to purification and growth. Zakāt is obligatory for all Muslims who are able to do so. It is the personal responsibility of each Muslim to ease the economic hardship of others and to strive towards eliminating inequality.[11] Zakāt consists of spending a portion of one's wealth for the benefit of the poor or needy, like debtors or travelers. A Muslim may also donate more as an act of voluntary charity (sadaqah), rather than to achieve additional divine reward.[12]

There are five principles that should be followed when giving the zakāt:

- The giver must declare to God his intention to give the zakāt.

- The zakāt must be paid on the day that it is due.

- After the offering, the payer must not exaggerate on spending his money more than usual means.

- Payment must be in kind. This means if one is wealthy then he or she needs to pay a portion of their income. If a person does not have much money, then they should compensate for it in different ways, such as good deeds and good behavior toward others.

- The zakāt must be distributed in the community from which it was taken.[13]

Sawm: Fasting

Three types of fasting (Siyam) are recognized by the Quran: Ritual fasting,[14] fasting as compensation for repentance (both from sura Al-Baqara),[15] and ascetic fasting (from Al-Ahzab).[16][17]

Ritual fasting is an obligatory act during the month of Ramadan.[18] Muslims must abstain from food and drink from dawn to dusk during this month, and are to be especially mindful of other sins.[18] Fasting is necessary for every Muslim that has reached puberty (unless he/she suffers from a medical condition which prevents him/her from doing so).[19]

The fast is meant to allow Muslims to seek nearness and to look for forgiveness from God, to express their gratitude to and dependence on him, atone for their past sins, and to remind them of the needy.[20] During Ramadan, Muslims are also expected to put more effort into following the teachings of Islam by refraining from violence, anger, envy, greed, lust, profane language, gossip and to try to get along with fellow Muslims better. In addition, all obscene and irreligious sights and sounds are to be avoided.[21]

Fasting during Ramadan is obligatory, but is forbidden for several groups for whom it would be very dangerous and excessively problematic. These include pre-pubescent children, those with a medical condition such as diabetes, elderly people, and pregnant or breastfeeding women. Observing fasts is not permitted for menstruating women. Other individuals for whom it is considered acceptable not to fast are those who are ill or traveling. Missing fasts usually must be made up for soon afterward, although the exact requirements vary according to circumstance.[22][23][24][25]

Hajj: pilgrimage to Mecca

The Hajj is a pilgrimage that occurs during the Islamic month of Dhu al-Hijjah to the holy city of Mecca. Every able-bodied Muslim is obliged to make the pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in their life.[26] When the pilgrim is around 10 km (6.2 mi) from Mecca, he/she must dress in Ihram clothing, which, for men, consists of two white sheets. Both men and women are required to make the pilgrimage to Mecca. After a Muslim makes the trip to Mecca, he/she is known as a hajj/hajja (one who made the pilgrimage to Mecca).[27] The main rituals of the Hajj include walking seven times around the Kaaba termed Tawaf, touching the Black Stone termed Istilam, traveling seven times between Mount Safa and Mount Marwah termed Sa'yee, and symbolically stoning the Devil in Mina termed Ramee.[27]

The pilgrim, or the haji, is honoured in the Muslim community. Islamic teachers say that the Hajj should be an expression of devotion to God, not a means to gain social standing. The believer should be self-aware and examine their intentions in performing the pilgrimage. This should lead to constant striving for self-improvement.[28] A pilgrimage made at any time other than the Hajj season is called an Umrah, and while not mandatory is strongly recommended. Also, they make a pilgrimage to the holy city of Jerusalem in their alms-giving feast.

Pillars of Shia Islam

Twelvers

Twelver Shia Islam has five Usul al-Din and ten Furu al-Din, i.e., the Shia Islamic beliefs and practices. The Twelver Shia Islam Usul al-Din, equivalent to a Shia Five Pillars, are all beliefs considered foundational to Islam, and thus classified a bit differently from those listed above.[29] They are:

- Tawhid (monotheism: belief in the oneness of Allah)

- Adl (divine justice: belief in Allah's justice)

- Nubuwwah (prophethood)

- Imamah (succession to Muhammad)

- Mi'ad (the day of judgment and the resurrection)

In addition to these five pillars, there are ten practices that Shia Muslims must perform, called the Ancillaries of the Faith[30] (Arabic: furūʿ al-dīn).

- Salah

- Sawm

- Zakat, similar to Sunni Islam, it applies to money, cattle, silver, gold, dates, raisins, wheat, and barley.

- Khums: an annual taxation of one-fifth (20%) of the gains that a year has been passed on without using. Khums is paid to the Imams; indirectly to poor and needy people.

- Hajj

- Jihad

- Enjoining good

- Forbidding wrong

- Tawalla: expressing love towards good.

- Tabarra: expressing disassociation and hatred towards evil.[31]

Ismailis

Isma'ilis have their own pillars, which are as follows:

- Walayah "Guardianship" denotes love and devotion to God, the prophets, and the Ismaili Imams and their representatives

- Tawhid, "Oneness of God".

- Salah: Unlike Sunni and Twelver Muslims, Nizari Ismailis reason that it is up to the current imām to designate the style and form of prayer.

- Zakat: with the exception of the Druze, all Ismaili madhhabs have practices resembling that of Sunni and Twelvers, with the addition of the characteristic Shia khums.

- Sawm: Nizaris and Musta'lis believe in both a metaphorical and literal meaning of fasting.

- Hajj: For Ismailis, this means visiting the imām or his representative and that this is the greatest and most spiritual of all pilgrimages. The Mustaali maintain also the practice of going to Mecca. The Druze interpret this completely metaphorically as "fleeing from devils and oppressors" and rarely go to Mecca.[32]

- Jihad "Struggle": "the Greater Struggle" and "the Lesser Struggle".

See also

References

- ↑ "Pillars of Islam". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2007-05-02.

- 1 2 "Pillars of Islam". Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies. United Kingdom: Oxford University. Retrieved 2010-11-17.

- ↑ "Five Pillars". United Kingdom: Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). Retrieved 2010-11-17.

- ↑ "The Five Pillars of Islam". Canada: University of Calgary. Retrieved 2010-11-17.

- ↑ "The Five Pillars of Islam". United Kingdom: BBC. Retrieved 2010-11-17.

- ↑ Hooker, Richard (July 14, 1999). "arkan ad-din the five pillars of religion". United States: Washington State University. Archived from the original on 2010-12-03. Retrieved 2010-11-17.

- ↑ "Religions". The World Factbook. United States: Central Intelligence Agency. 2010. Retrieved 2010-08-25.

- ↑ Hajj

- ↑ From the article on the Pillars of Islam in Oxford Islamic Studies Online

- ↑ Matthew S. Gordon and Martin Palmer, ''Islam'', Info base Publishing, 2009. Books.Google.fr. 2009. p. 87. ISBN 9781438117782. Retrieved 2012-08-26.

- ↑ Ridgeon (2003), p.258

- ↑ Zakat, Encyclopaedia of Islam Online

- ↑ Zakat Alms-giving

- ↑ Quran 2:183–187

- ↑ Quran 2:196

- ↑ Quran 33:35

- ↑ Fasting, Encyclopedia of the Qur'an (2005)

- 1 2 Farah (1994), p.144-145

- ↑ talhaanjum_9

- ↑ Esposito (1998), p.90,91

- ↑ Tabatabaei (2002), p. 211,213

- ↑ "For whom fasting is mandatory". USC-MSA Compendium of Muslim Texts. Archived from the original on 8 March 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-18.

- ↑ Quran 2:184

- ↑ Khan (2006), p. 54

- ↑ Islam, The New Encyclopædia Britannica (2005)

- ↑ Farah (1994), p.145-147

- 1 2 Hoiberg (2000), p.237–238

- ↑ Goldschmidt (2005), p.48

- ↑ See chapter on "Islamic Beliefs (the Pillars of Islam)" in Invitation to Islam by Sayed Moustafa Al-Qazwini. http://www.al-islam.org/invitation/

- ↑ Walsh, John Evangelist. Walking shadows: Orson Welles, William Randolph Hearst, and Citizen Kane. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press/Popular Press, 2004.

- ↑ "The Fundamental Beliefs of Muslims". Comprehensive Database Mstbsryn, missionaries and Rhyaftgan.

- ↑ "Isma'ilism". Retrieved 2007-04-24.

Bibliography

Books and journals

- Brockopp, Jonathan; Tamara Sonn; Jacob Neusner (2000). Judaism and Islam in Practice: A Sourcebook. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-21673-7.

- Farah, Caesar (1994). Islam: Beliefs and Observances (5th ed.). Barron's Educational Series. ISBN 978-0-8120-1853-0.

- Muhammad Hedayetullah (2006). Dynamics of Islam: An Exposition. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-55369-842-5.

- Khan, Arshad (2006). Islam 101: Principles and Practice. Khan Consulting and Publishing, LLC. ISBN 0-9772838-3-6.

- Kobeisy, Ahmed Nezar (2004). Counseling American Muslims: Understanding the Faith and Helping the People. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-313-32472-7.

- Momen, Moojan (1987). An Introduction to Shi`i Islam: The History and Doctrines of Twelver Shi`ism. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-03531-5.

- Levy, Reuben (1957). The Social Structure of Islam. UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-09182-4.

- Muhammad Husayn Tabatabaei (2002). Islamic teachings: An Overview and a Glance at the Life of the Holy Prophet of Islam. R. Campbell (translator). Green Gold. ISBN 0-922817-00-6.

- Arthur Goldschmidt Jr. & Lawrence Davidson (2005). A Concise History of the Middle East (8th ed.). Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-4275-7.

- Hoiberg, Dale; Indu Ramchandani (2000). Students' Britannica India. Encyclopædia Britannica (UK) Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85229-760-5.

- Ridgeon, Lloyd (2003). Major World Religions (1st ed.). RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 978-0-415-29796-7.

Encyclopedias

- P.J. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam Online. Brill Academic Publishers. ISSN 1573-3912.

- Salamone Frank, ed. (2004). Encyclopedia of Religious Rites, Rituals, and Festivals (1st ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-94180-8.

External links

- Tenets of Islam

- Pillars of Islam in Oxford Islamic Studies Online

- Pillars of Islam. A brief description of the Five Pillars of Islam.

- Five Pillars of Islam. Complete information about The Five Pillars of Islam.