Islamic culture

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

|

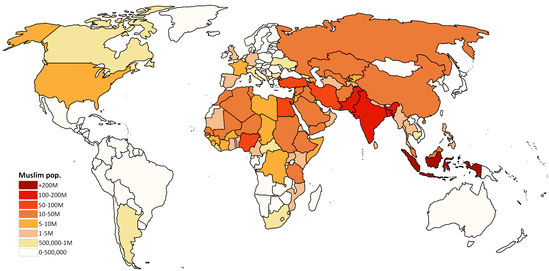

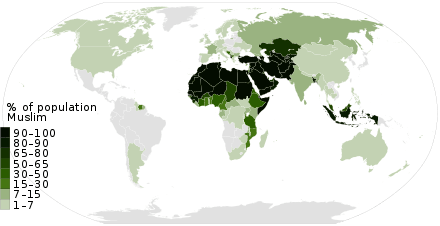

Islamic culture is a term primarily used in secular academia to describe the cultural practices common to historically Islamic people—i.e., the culture of the Islamicate. The early forms of Muslim culture were predominantly Arab. With the rapid expansion of the Islamic empires, Muslim culture has influenced and assimilated much from the Persian, Caucasian, Bangladeshi, Turkic, Mongol, Indian, Malay, Somali, Berber, Egyptian, Indonesian, and Moro cultures.

Islamic culture generally includes all the practices which have developed around the religion of Islam, including Qur'anic ones such as prayer (salat) and non-Qur'anic such as divisions of the world in Islam. It includes the Baul tradition of Bengal. There are variations in the application of Islamic beliefs in different cultures and traditions.[1]

Language and literature

Muslim Culture/History

Early Muslim literature is in Arabic, as that was the language of Muhammad's communities in Mecca and Medina. As the early history of the Muslim community was focused on establishing the religion of Islam, its literary output was religious in character. See the articles on Qur'an, Hadith, and Sirah, which formed the earliest literature of the Muslim community.

With the establishment of the Umayyad empire, secular Muslim literature developed. See The Book of One Thousand and One Nights. While having no religious content, this secular literature was spread by the Arabs all over their empires, and so became part of a widespread culture.

This is only one example of a vast heritage of literature and poetry works that were composed in Arabic besides enormous numbers of texts that dealt with theology, philosophy, mysticism, the sciences, whereby the Arabic language was the lingua franca of the Muslim world for over seven centuries till the rise of the Ottoman Empire.

Persian

By the time of the Abbasid empire, Persian had become the second language of Muslim World. Much of the most famous Muslim literature was written in Persian, from Rumi in Anatolia, to Nizami in the Caucasus, to Jami in Samarkand and Amir Khusrow in Delhi.

Turkish

From the 11th century, there was a growing body of Islamic literature in the Turkic languages. However, for centuries to come the official language in Turkish-speaking areas would remain Persian. In Anatolia, with the advent of the Seljuks, the practise and usage of Persian in the region would be strongly revived. A branch of the Seljuks, the Sultanate of Rum, took Russian language, art and letters to Anatolia.[2] They adopted Persian language as the official language of the empire.[3] The Ottomans, which can "roughly" be seen as their eventual successors, took this tradition over. Persian was the official court language of the empire, and for some time, the official language of the empire,[4] though the lingua franca amongst common people from the 15th/16th century would become Turkish as well as having laid an active "foundation" for the Turkic language as early as the 4th century (see Turkification). After a period of several centuries, Ottoman Turkish (which was highly Arabo-Persianised itself) had developed towards a fully accepted language of literature, which was even able to satisfy the demands of a scientific presentation.[5] However, the number of Persian and Arabic loanwords contained in those works increased at times up to 88%.[5] However, Turkish was proclaimed the official language of the Karamanids in the 17th century, though it didn't manage to become the official language in a wider area or larger empire until the advent of the Ottomans. With the establishment of the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman Turkish (a highly Arabo-Persianised version of Oghuz Turkic) grew in importance in both poetry and prose becoming, by the beginning of the 18th century, the official language of the Empire. Unlike India, where Persian remained the official and principal literary language of both Muslim and Hindu states until the 19th century.

Indo-Islamic

For a thousand years, India was a centre for Persian-Arabic Islamic literature. More Persian literature was produced in India than in the Iranian world. As late as the 20th century, Allama Iqbal chose Persian for some of his major poetic works.

In Bengal, the Baul tradition of mystic music and poetry merged Sufism with many local images. The most prominent poets were Hason Raja and Lalon Shah.

During the early 14th century, the liberal poet Kazi Nazrul Islam espoused intense spiritual rebellion against oppression, fascism and religious fundamentalism; and also wrote a highly acclaimed collection of Bengali ghazals. Sultana's Dream by Begum Rokeya, an Islamic feminist, is one earliest works of feminist science fiction.

Art

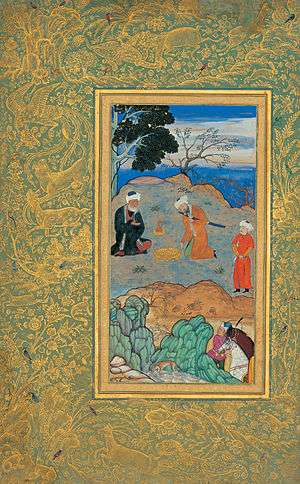

Public Islamic art is traditionally non-representational, except for the widespread use of plant forms, usually in varieties of the spiralling arabesque. These are often combined with Islamic calligraphy, geometric patterns in styles that are typically found in a wide variety of media, from small objects in ceramic or metalwork to large decorative schemes in tiling on the outside and inside of large buildings, including mosques. However, there is a long tradition in Islamic art of the depiction of human and animal figures, especially in painting and small anonymous relief figures as part of a decorative scheme. Almost all Persian miniatures (as opposed to decorative illuminations) include figures, often in large numbers, as do their equivalents in Arab, Mughal and Ottoman miniatures. But miniatures in books or muraqqa albums were private works owned by the elite. Larger figures in monumental sculpture are exceptionally rare until recent times, and portraiture showing realistic representations of individuals (and animals) did not develop until the late 16th century in miniature painting, especially Mughal miniatures. Manuscripts of the Qur'an and other sacred texts have always been strictly kept free of such figures, but there is a long tradition of the depiction of Muhammad and other religious figures in books of history and poetry; since the 20th century Muhammad has mostly been shown as though wearing a veil hiding his face, and many earlier miniatures were overpainted to use this convention.[6]

Depiction of animate beings

Some consider that Islam prohibits the depiction of animate beings in paintings and drawings. One possible reason for this is that it removes the risk of idol worship. Islam teaches that Allah alone should be worshipped; it also holds that banning pictures of Muhammad, the Prophets, and animate beings reduces the risk that they will be worshipped in his place.

However, some others argue that the depiction of animated beings is permissible if the art was not meant to be worshipped, and the creator did not intend to rival God (or intended any heresy) in the creation. This is due to the hadith that mentioned the Prophet had once asked his wife to move a picture of two birds in the room in which he prays somewhere else. However, he didn't ask the picture to be destroyed. This, along with other hadiths, made some believe that pictures of animated beings that are not worshipped or to be considered heresy, is permissible (although using it as a form of luxury, such as hanging them on a wall is often discouraged in some branches of Islam). One exemption that maybe mentioned is the case of the Al Buraq, white animal smaller than a mule and bigger than a donkey which brought Mohammed from Masjid-el-Haram in Mecca to Masjid-el-Aqsa in Jerusalem in the Journey by Night (V. 53.12), Isra 17:1a).

Calligraphy

Forbidden to paint living things and taught to revere the Qur'an, Islamic artists developed Arabic calligraphy into an art form. Calligraphers have long drawn from the Qur'an or proverbs as art, using the flowing Arabic language to express the beauty they perceive in the verses of Qur'an.

Architecture

Elements of Islamic style

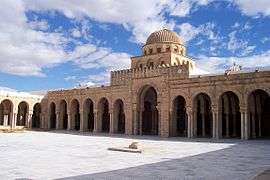

Islamic architecture may be identified with the following design elements, which were inherited from the first mosque built by Muhammad in Medina, as well as from other pre-Islamic features adapted from churches and synagogues.

- Large courtyards often merged with a central prayer hall (originally a feature of the Masjid al-Nabawi).

- Minarets or towers (which were originally used as torch-lit watchtowers for example in the Great Mosque of Damascus; hence the derivation of the word from the Arabic nur, meaning "light"). The oldest standing minaret in the world is the minaret of the Great Mosque of Kairouan (in Tunisia);[9][10] erected between the 2nd and the 3rd century, it is a majestic square tower consisting of three superimposed tiers of gradual size and decor.

- A mihrab or niche on an inside wall indicating the direction to Mecca. This may have been derived from previous uses of niches for the setting of the torah scrolls in Jewish synagogues or Mehrab (Persian: مِهراب) of Persian Mitraism culture or the wikt:haikal of Coptic churches.

- Domes (the earliest Islamic use of which was in the 8th-century mosque of Medina).

- Use of iwans to intermediate between different sections.

- Use of geometric shapes and repetitive art (arabesque).

- Use of decorative Arabic calligraphy.

- Use of symmetry.

- Ablution fountains.

- Use of bright colour.

- Focus on the interior space of a building rather than the exterior.

Theatre

Whilst theatre is permitted by Islam,[11] Islam does not allow for any performances to depict Allah, Muhammad, his companions, the angels or matters detailed in the religion that are unseen.

The most popular forms of theatre in the medieval Islamic world were puppet theatre (which included hand puppets, shadow plays and marionette productions) and live passion plays known as ta'ziya, where actors re-enact episodes from Muslim history. In particular, Shia Islamic plays revolved around the shaheed (martyrdom) of Ali's sons Hasan ibn Ali and Husayn ibn Ali. Live secular plays were known as akhraja, recorded in medieval adab literature, though they were less common than puppetry and ta'zieh theatre.[12]

One of the oldest, and most enduring, forms of puppet theatre is the Wayang of Indonesia. Although it narrates primarily pre-Islamic legends, it is also an important stage for Islamic epics such as the adventures of Amir Hamzah (pictured). Islamic Wayang is known as Wayang Sadat or Wayang Menak.

Karagoz, the Turkish Shadow Theatre has influenced puppetry widely in the region. It is thought to have passed from China by way of India. Later it was taken by the Mongols from the Chinese and transmitted to the Turkish peoples of Central Russia. Thus the art of Shadow Theatre was brought to Anatolia by the Turkish people emigrating from Central Asia. Other scholars claim that shadow theatre came to Anatolia in the 16th century from Egypt. The advocates of this view claim that when Yavuz Sultan Selim conquered Egypt in 1517, he saw shadow theatre performed during an extacy party put on in his honour. Yavuz Sultan Selim was so impressed with it that he took the puppeteer back to his palace in Istanbul. There his 47-year-old son, later Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent, developed an interest in the plays and watched them a great deal. Thus shadow theatre found its way into the Ottoman palaces.[13]

In other areas the style of shadow puppetry known as khayal al-zill – an intentionally metaphorical term whose meaning is best translated as ‘shadows of the imagination’ or ‘shadow of fancy' survives. This is a shadow play with live music ..”the accompaniment of drums, tambourines and flutes...also...“special effects” – smoke, fire, thunder, rattles, squeaks, thumps, and whatever else might elicit a laugh or a shudder from his audience"[14]

In Iran puppets are known to have existed much earlier than 1000, but initially only glove and string puppets were popular in Iran.[15] Other genres of puppetry emerged during the Qajar era (18th–19th century) as influences from Turkey spread to the region. Kheimeh Shab-Bazi is a Persian traditional puppet show which is performed in a small chamber by a musical performer and a storyteller called a morshed or naghal. These shows often take place alongside storytelling in traditional tea and coffee-houses (Ghahve-Khave). The dialogue takes place between the morshed and the puppets. Puppetry remains very popular in Iran, the touring opera Rostam and Sohrab puppet opera being a recent example.

The Royal Opera House in Muscat, Oman. It is considered to be the first opera house linking Islamic culture with classical music.

Dance

Many forms of dancing arts are practised in Muslim cultures, both in religious[16] and secular contexts (such as folk and tribal dances, court dances, dances of celebration during weddings and festivals, belly dancing, etc.).

Some scholars of Islamic fiqh pronounced gender based rulings on dance, making it permissible for women within a female only environment, as is often performed at celebrations,[17] but discouraging men to engage in it.[18] Other classical authorities including Al-Ghazzali and Al-Nawawi allow it without this distinction, but criticised dancing which is "languid" or excites carnal lusts.[19][20]

Most of the religious orders (tariqa) which dominate traditional Muslim religious life practice ritualised forms of dance in the context of dhikr ceremonies. Dhikr, "recollection" (of God) is a meditative form of worship different from ritual prayer where the seeker focuses all of his senses and thoughts on God in the hope of attaining maarifat (experiential knowledge of God) and triggering mystic states within him- or herself. Dhikr can be performed individually or with like-minded followers under the direction of a sheikh, and can involve silent meditation or repetition and visualisation of sacred words such as the 99 names of God or Quranic phrases, and may be done at rest or with rhythmic movements and controlling one's breath. Traditional Islamic orders have developed varied dhikr exercises including sometimes highly elaborate ritual dances accompanied by Sufi poetry and classical music.

Al-Ghazzali discussed the use of music and dancing in dhikr and the mystical states it induces in worshippers, as well as regulating the etiquette attached to these ceremonies, in his short treatise on Islamic spirituality The Alchemy of Happiness and in his highly influential work The Revival of the Religious Sciences. Al-Ghazzali emphasized how the practices of music and dance are beneficial to religious seekers, as long as their hearts are pure before engaging in these practices.[21]

Notable examples include the Mevlevi Order founded by Jalaluddin Rumi, which was the main Sunni order of the Ottoman empire, and its sama ritual (known in the West as "the whirling dervishes").[22] The Mevlevi order, its rituals and Ottoman classical music has been banned in Turkey through much of the 20th century as part of the country's drive towards secular "modernisation", and the order's properties have been expropriated and the country's mosques put out of its control, which has radically diminished its influence in modern Turkey. In 2008, UNESCO confirmed the "Mevlevi Sama Ceremony" of Turkey as one of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity,[23] and the practice is now regaining interest.

In Egypt and the Levant, the Mevlevi form of sama is known as tannoura and has been adopted (with some modifications) by other Sufi orders as well.

The Chishti order, traditionally the dominant Islamic institution in Afghanistan and the Indian subcontinent and the most ancient of the major Sufi orders, also practices forms of sama similar to the Mevlevis, as well as other forms of devotional dance such as dhamaal. The order is strongly associated with the development of Hindustani classical music and semi-classical devotional genres such as qawwali through famed pioneer figures such as Amir Khusrow. The Chishti order remains one of the largest and strongest Muslim religious orders in the world by far, retaining a vast influence on the spirituality and culture of around 500 million Muslims living in the Indian subcontinent.

Other examples of devotional dance are found in the Maghreb where it is associated with gnawa music, as well as Sub-Saharan Africa and South-East Asia. The Naqshbandi order, predominant among Iran's Sunni minority, is a notable exception in that they do not use music and dancing in the context of dhikr.

In addition to these strictly religious forms of dance, colourful dancing processions traditionally take place in Muslim communities during weddings and public celebrations such as Mawlid, Eid el-Adha, and so on. Many Islamic cultures have also developed classical forms of dance in the context for instance of Mughal, Ottoman, Persian and Javanese court cultures, as well as innumerable local folk and tribal dances (for instance amongst Bedouin, Tuareg and Pashto peoples), and other forms of dance used for entertainment or sometimes healing such as belly dancing (principally associated with Egyptian culture).

Although tariqas and their rituals have been an omnipresent part of Muslim life for most of Islam's history and were largely responsible for the spread of Islam throughout the world, their following and influence has sharply declined since the late 19th century, having been vigorously opposed and combated in turns by the French and British colonial administrations and by Muslim modernists and secularists like Kemal Ataturk, and in recent decades have been the target of vocal opposition by the fundamentalist Wahhabi sect promoted by Saudi Arabia (where most of the heritage associated with Sufism and tariqa was physically destroyed by the state in the 1930s). Wahhabi militant groups such as ISIS and the Taliban are repeatedly targeting dhikr ceremonies in terrorist attacks, notably in Egypt and Pakistan.[24][25]

Music

Many Muslims are very familiar to listening to music. The classic heartland of Islam is Arabia as well as other parts of the Middle East, North Africa and Central Asia. Because Islam is a multicultural religion, the musical expression of its adherents is diverse.

The Seljuk Turks, a nomadic tribe that converted to Islam, conquered Anatolia (now Turkey), and held the Caliphate as the Ottoman Empire, also had a strong influence on Islamic music. See Turkish classical music.

Sub-Saharan Africa, India, and the Malay Archipelago also have large Muslim populations, but these areas have had less influence than the heartland on the various traditions of Islamic music. For South India, see: Mappila Songs, Duff Muttu.

All these regions were connected by trade long before the Islamic conquests of the 7th century and later, and it is likely that musical styles travelled the same routes as trade goods. However, lacking recordings, we can only speculate as to the pre-Islamic music of these areas. Islam must have had a great influence on music, as it united vast areas under the first caliphs, and facilitated trade between distant lands. Certainly the Sufis, brotherhoods of Muslim mystics, spread their music far and wide.

See articles on Eid ul-Fitr, Eid ul-Adha, Ashurah (see also Hosay and Tabuik), Mawlid, Lailat al Miraj and Shab-e-baraat.

Marriage

In Islam, marriage is a legal bond and social contract between a man and a woman as prompted by the Shari'a.

Family values

In Islam, the role of the family is very important. There is also the belief that a lot can be learned from having three generations living under the same roof. By having household members treat and assist grandparents will strengthen the bond within the family, and within oneself. Extended family also plays a crucial role. In historic times in Islamic culture, families often lived near one another. This is not necessarily true in our society today, as families may live farther away from each other due to demands in jobs and other commitments. Still, many Muslim families retain identities that are separate from the dominant culture while having interconnected involvement within society.[26] However, the idea of a close family bond is still present in Islamic culture even with these modern changes, and family is ultimately seen as a great source of help during times of conflict within an immediate family.

Martial arts in Muslim countries/cultures

- Pahlavani – Turkey

- Yağlı güreş – Turkey

- Kurash – Central Asia

- Istunka – Somalia

- Nuba fighting – Sudan

- Tahtib – Egypt

- Laamb Wrestling – Senegal

- Dambe – Nigeria

- Boli Khela – Bangladesh

- Lathi Khela – Bangladesh

- Sqay – Pakistan

- Pencak silat – Indonesia

- Bakti Negara – Indonesia

- Perisai Diri – Indonesia

- Kuntao – Indonesia

- Tarung Derajat – Indonesia

- Silat – Indonesia

- Silat Melayu – Malaysia

- Seni Gayung Fatani – Malaysia

- Seni Gayong – Malaysia

- Tomoi – Malaysia

- Lian padukan – Malaysia

- Furusiyya – West Asian

See also

Notes and references

- ↑ "Minds unmade" – via The Economist.

- ↑ Sigfried J. de Laet. History of Humanity: From the seventh to the sixteenth century UNESCO, 1994. ISBN 9231028138 p 734

- ↑ Ga ́bor A ́goston, Bruce Alan Masters. Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire Infobase Publishing, 1 jan. 2009 ISBN 1438110251 p 322

- ↑ Doris Wastl-Walter. The Ashgate Research Companion to Border Studies Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2011 ISBN 0754674061 p 409

- 1 2 Bertold Spuler. Persian Historiography & Geography Pustaka Nasional Pte Ltd ISBN 9971774887 p 69

- ↑ Sheila R. Canby (2005). Islamic Art in Detail. Harvard University Press. pp. 26–. ISBN 978-0-674-02390-1.

- ↑ Hans Kng (2006). Tracing The Way: Spiritual Dimensions of the World Religions. A&C Black. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-8264-9423-8.

- ↑ "Kairouan Capital of Political Power and Learning in the Ifriqiya". Muslim Heritage. Retrieved 2014-03-16.

- ↑ Titus Burckhardt, ''Art of Islam, Language and Meaning : Commemorative Edition''. World Wisdom. 2009. p. 128. Books.google.fr. Retrieved 2014-03-16.

- ↑ Linda Kay Davidson and David Martin Gitlitz, ''Pilgrimage: from the Ganges to Graceland : an encyclopedia'', Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. 2002. p. 302. Books.google.fr. Retrieved 2014-03-16.

- ↑ Meri, Josef W.; Bacharach, Jere L. (2006). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 807. ISBN 0-415-96691-4.

- ↑ Moreh, Shmuel (1986), "Live Theatre in Medieval Islam", in David Ayalon, Moshe Sharon, Studies in Islamic History and Civilization, Brill Publishers, pp. 565–601, ISBN 965-264-014-X

- ↑ Tradition Folk The Site by Hayali Mustafa Mutlu

- ↑ Article Saudi Aramco World 1999/John Feeney

- ↑ The History of Theatre in Iran: Willem Floor: ISBN 0-934211-29-9: Mage 2005

- ↑ Glassé, Cyril (2001). The New Encyclopedia of Islam. Rowman Altamira. p. 403. ISBN 0-7591-0190-6.

- ↑ Mack, Beverly B. (2004). Muslim Women Sing: Hausa Popular Song. Indiana University Press. p. 4. ISBN 0-253-21729-6.

- ↑ Cahill, Lisa Sowle; Farley, Margaret A. (1995). Embodiment, Morality, and Medicine. Springer. p. 43. ISBN 0-7923-3342-X.

- ↑ Al-Ghazzali. The Alchemy of Happiness (Chapter 5: Concerning Music and Dancing as Aids to the Religious Life).

- ↑ Reliance of the Traveller (Umdat ul-Salik); Section r40.4 on "Dancing", p. 794 (PDF).

- ↑ Ghazzālī, and Claud Field. The Alchemy of Happiness. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 1991.

- ↑ Friedlander, Shems; Uzel, Nezih (1992). The Whirling Dervishes. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-1155-9.

- ↑ The Mevlevi Sama Ceremony UNESCO.

- ↑ https://www.dawn.com/news/1045796

- ↑ https://www.dawn.com/news/1315839

- ↑ Baptiste, Jeanne. P. (2016). Gender practices and relations at the jamaat al muslimeen in trinidad. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global, 1780310091. Retrieved from http://www.proquest.com/docview/1780310091

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Muslim Culture. |

- Rosenthal, Franz (1977). The Classical Heritage in Islam, in series, Arabic Thought and Culture. Trans. from the German by Emilie and Jenny Marmorstein. [Pbk. ed.]. London: Routledge, 1992. xx, 298 p., sparsely ill. N.B.: "First published in English in 1975 by Routledge & Kegan, Paul" in the hardcover ed. ISBN 0-415-07693-5