Architecture of London

London is the second largest urban area – and largest city (see List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits) – in the European Union area; as the ancient city of Londinium founded in the first century CE and nearly continuously inhabited, it is not characterised by any single predominant architectural style but areas of the city exhibit very strong and influential urban qualities which have deeply influenced urban planning globally. Considered with the administrative capital of the City of Westminster, relatively few structures predate the Great Fire of 1666, with notable exceptions including the Tower of London, Westminster Abbey, Banqueting House, Queens House, portions of St James's Palace, London Charterhouse, Lambeth Palace and scattered Tudor survivals.

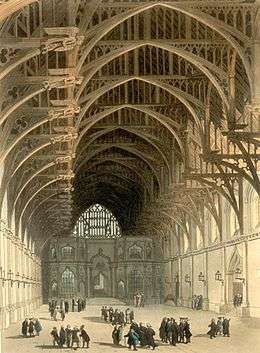

The ancient City of London initially laid out as a planned Roman city in the 60s CE alongside the River Thames contains a wide variety of styles, from Roman and Romanesque archaeological remains to remnants of the medieval Gothic walled city, English Renaissance buildings by Inigo Jones to English Baroque by Wren and Nicholas Hawksmoor, Neoclassical and Imperial Gothic financial institutions of the 18th and 19th century such as the Royal Exchange, the urban set-piece of Regent Street and Regents Park by John Nash and the Bank of England by John Soane, to the early 20th century Old Bailey (England and Wales' central criminal court) and the Modernist 1960s Royal Festival Hall, Barbican Estate and Royal National Theatre by Denys Lasdun.

Notable recent tall buildings are the 1980s skyscraper Tower 42, the Lloyd's building with services running along the outside of the structure, and the 2004 Swiss Re building, nicknamed the "Gherkin" which set a new precedent for recent high-rise developments including Richard Rogers Leadenhall Building.

London's historic mid-rise character has been, in some instances controversially,[1][2] altered over the last generation with new high-rise 'skyscrapers' erected reflecting London's predominance as a global financial centre. Renzo Piano's 310m The Shard is the tallest building in the European Union, the fourth-tallest building in Europe and the 96th-tallest building in the world[3][4][5]

Other notable modern buildings include City Hall in Southwark with its distinctive ovular shape, the Postmodernist British Library in Somers Town and No 1 Poultry by James Stirling, the Great Court of the British Museum, and the striking Millennium Dome next to the Thames east of Canary Wharf. The 1933 Battersea Power Station and the Tate Modern by George Gilbert Scott and Herzog de Meuron are striking examples of adaptive re-use, whilst the railway termini are globally significant examples of Victorian railway architecture, most notably St Pancras and Paddington.

The city of Westminster is the ancient political centre of power and contains the globally recognised Palace of Westminster and the iconic clocktower of Big Ben. The city contains numerous monuments, from the ancient heart of London at London Stone to the seventeenth century The Monument to the Great Fire of London to Marble Arch and Wellington Arch, the Albert Memorial and Royal Albert Hall in Kensington. Nelson's Column is an internationally recognised monument in Trafalgar Square often now regarded as the centre of London.

Since 2004, the London Festival of Architecture is held in June, and focuses on the importance of architecture and design in London today. One quarter of UK architects operate from London with the majority of the most high-profile global practices based in London[6] including Zaha Hadid Architects, Foster and Partners, Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, David Chipperfield and David Adjaye among the most well known internationally. In September Open House weekend offers an annual opportunity to visit architecture normally closed to the public free of charge from grand public buildings such as the Bank of England to contemporary private housing.

Prehistoric

Although no pre-Roman settlement is known, there was a prehistoric crossing point at Deptford and also at Vauxhall Bridge[7] and some prehistoric remains are known from archaeology of the River Thames.[8] It is likely that the course of Watling Street follows a more ancient pathway. Ancient Welsh legend claims the city of the Trinovantes - dedicated to the god Lud (Caer Llud) was founded by the followers of Bran the Blessed whose severed head is said to be buried under the White Tower facing the continent.[9]

Roman Architecture (60-500CE)

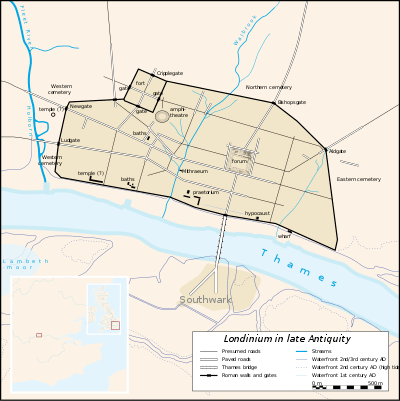

Londinium was initially founded as a military trading port while the first capital of the province was at Camulodunum. However following the Boudican Revolt of 61, during which both cities were razed to the ground, the capital was removed to London which rapidly grew to preeminence with the establishment of a Forum and provincial Praetorium. The city was originally laid out to a classical plan as many other cities in Britannia and throughout Europe in a roughly rectangular form with the south side formed by the River Thames and divided into blocks of insulae.[10] Two east-west streets (now Cheapside and Lower Thames Street led from Newgate and Ludgate to form the cardo presumably leading to a lost gate (or gates) at the present location of the Tower of London which exited to Canterbury and Dover. Bishopsgate, as an extension of Watling Street formed the decumanus maximus crossing the river from Billingsgate over the ancient London Bridge to Southwark and the south coast road beyond. The Forum was located at Leadenhall Market - said to be the largest building north of the Alps in ancient times - remains can still be visited in the basement of some of the market shops.[11] The rectangular walled and gridded city was soon extended to the west over the River Walbrook, north towards marshy Moorfields and east to the area later known as Minories[12] where a Romano-British tomb sculpture of an eagle was found in 2013 suggesting the site lay outside the city limits in the early second century.[13] A significant portion of the amphitheatre remains beneath the London Guildhall square and a Roman bathing complex is accessible in the basement of 100 Lower Thames Street.[14] The square Castrum was located at the northeast of the city at the Barbican close to the Museum of London where significant sections of the Roman London Wall remain. For centuries afterward, the centre of London was reckoned from the London Stone claimed in the past to be a fragment of ancient masonry from the ancient Thameside Governor's Palace, though this cannot now be verified.[15] Late Roman private houses of leading Christians are thought to have been the foundation of the earliest churches- mosaic remains in the crypt at All Hallows by the Tower and may also have been the case for St Pauls Cathedral - its growing significance over centuries has distorted the once-straight strada on which the site once stood.

Georgian Neoclassical Architecture in London

During the Georgian era (1714-1830), London increased in size greatly to take in previously separate village such as Islington and Clapham, hence much of inner London is dominated by Georgian buildings. The 'Georgian' style is the British form of Neoclassical architecture heavily influenced by the liberal whig political ideology of Palladianism;[16] it is especially influenced by neo Renaissance proportions which ultimately originate in Italian architecture, with strong influence from French Architecture and especially the Dutch Baroque architecture under William & Mary with strict emphasis on plain, unadorned brickwork, geometrical harmony and restrained classically inspired ornament as at Kensington Palace begun by Christopher Wren after 1689. Key architects in the development of the London architecture through the period begin with Inigo Jones Queens House (predating the Georgian period entirely), through Wren at the west wing of Hampton Court Palace, Colen Campbell, John Nash (architect), Robert Adams (architect) and John Soane. Areas such as, for example, Mayfair, Bloomsbury, Regents Park, Islington and Kensington have very high proportions of properties surviving from the period which have become the archetypical 'London Townhouses' and being, highly desirable, fetch some of the highest private property prices in the world.

Domestic houses in London[17] are distinctive for their sunken basements built on brick arch foundations, rusticated base storey, taller piano nobile reception floor and attic storey. They are generally built from buff (pale yellow) London Stock Brick to golden section proportions, often generously spanning triple bay frontages with 'implied' columns or pilasters and carefully proportioned and very large off-white sash windows , slate mansard roofs above an attic pediment. They were grouped in formal Garden squares, crescents and terraces with wide pavements supported on brick vaults on wide, straight public streets often with private access to romantically landscaped gardens. Later encroachment of commercial properties has significantly reduced the apparent width of historic streets in many parts of London where the original plans was comparable or in excess of those found in Continental urban planning.[18] The area of Spitalfields is well known in London for its density of extant very early Georgian properties which exhibit some unusual continental features;[19] Soho - particularly Meard Street[20] - and Westminster also preserve a large number of properties at an early stage of development of the style.

A typical house was designed to accommodate a single family with front and back room on each floor and a partial-width rear 'closet' wing projection. The ground floor was reserved for business, the tall piano nobile for formal entertaining and upper storeys with family bedrooms all accessed from a stair positioned on the side party. Servants accommodated in the below ground kitchen and in attic rooms in the roof Each of the distinctions in function was subtly indicated in the decorative scheme of the facade by the sequential height of openings, projecting cornices and restrained decorative mouldings such as round headed arches and rustication at the base and diminishing columns, sculptural capitals, balustrades and friezes expressing the top.

Diagnostic features include:

- A tall panelled front door with an arched fanlight often flanked by columns and covered by a pedimented canopy is reached up a short walkway which extend from the street, arching over the basement cavity and protected from burglary by a run of wrought iron security railings.

- Sash windows which allow the window to be held open on corded lead weights to ventilate the room - developed in Holland and first seen in the Royal Palaces, they became common in Georgian times - previously casement windows had been the norm. The sash box joinery and ovolo or astragal moulded window frames were designed to be as slim and unobtrusive as achievable using the largest available sheets of glass in either a '6 over 6' or '6 over 9' pattern. Since the 1980s, these are often now painted in brilliant white, however this modern colour did not exist in the period, originally these were painted ivory off-white, pale yellow or other darker colours of the period.

- Window openings in the proportion of 1:2 or the golden section - the windows were headed by the Dutch style flat arch often made from gauged brickwork in the finest properties.

- The roof is often hidden by a parapet above an attic frieze. This was initially to reduce the spread of fire, however in much of London parapets were added to Georgian houses for aesthetic reasons alone. From the street the building appears as if it has a flat roof, but from the rear one can see that there is a double pitched 'butterfly'roof.

- Elevational classical adornments such as rustication, pilasters, columns, medallions, friezes, cornices and false pediments often formed in timber, stucco or natural stone are obvious indicators of wealth and status - however much care and restraint was exercised to avoid the excessive flamboyance of continental architecture, with a marked preference for severe simplicity, honesty of means and sparseness of ornament in line with Protestant and neo-Palladian thinking, best exemplified by the work of Scottish Enlightenment architect Robert Adams - a philosophy extended to interior furnishing by the Thomas Chippendale furniture.

- Suburban buildings are usually constructed from London stock brick, which have a yellowish buff colour (which often appears grey - see 10 Downing Street). More prestigious houses are rendered with stucco or built from imported natural stone.

- Chimney breast were located in shared party walls with gable parapets projecting above the roof line. The great number of chimneypots on London properties indicate the relative wealth of the inhabitants serving fireplaces in every room.

Regency Architecture

London possesses some of the finest examples from the late-Georgian phase of British architecture known as Regency, which is aesthetically distinct from early Georgian architecture, though it falls within the scope of Georgian architecture and continues the stylistic trend of Neoclassicism. Technically the Regency era only lasted between the years 1811-20, when the Prince Regent ruled as proxy for his incapacitated father George III, but the distinctive trends in art and architecture in fashion during the Regency extended roughly the first 40 years of the 19th century.[21] Regency is above all a very stringent form of Classicism, directly referencing Graeco-Roman architecture and structures.[22] Regency employed enhanced ornamentation like friezes with high and low relief figural or vegetative motifs, statuary, urns, and porticos, all the while keeping with the clean lines and symmetry of early Georgian architecture.[23] Typically Georgian features like sash windows were retained, along with first-floor balconies, which became especially popular in the Regency period, utilizing either delicate wrought iron scrollwork or traditional balusters.[24]

The most noticeable difference between early-Georgian and Regency architecture is the covering of previously exposed brick facades with stucco painted in cream tones to imitate marble or natural stone.[25] John Nash was the leading proponent of Regency Classicism, and some of his finest works survive in London.[26] These include Nash's grand residential terraces surrounding Regents Park: Cumberland Terrace, Cambridge Terrace, Park Square, and Park Crescent.[27] Nash's heavy use of stucco on these buildings was often deceptive as much as it was aesthetic: stucco served to obscure inferior-quality construction caused by hurried building and cost-cutting measures because Nash had a financial interest in the Regent's Park developments.[28]

.jpg)

The designs for other Regents Park terraces (Cornwall, Clarence and York) were entrusted to Decimus Burton, an architect who specialized in Greek Revival.[29][30] These imposing terraces employ all the signature features of Regency Classicism: imposing, temple-like frontages covered in gleaming stucco with projecting porches, porticos with Corinthian or Ionic capitals, large pediments, and figural friezes extending along the upper part of the facades.[31] Burton's design for the Athenaeum Club (1830) on Pall Mall, whose sculptural frieze was modelled on the recently acquired Elgin Marbles in the British Museum, is another splendid example of Regency Classicism.[32]

Only steps away from the Athenaeum, Nash designed what has been called "London's finest Regency terrace", Carlton House Terrace (1829), on the site of the Prince Regent's demolished Carlton House.[33] Carlton House was demolished in 1826 after the new King, George IV, moved to Buckingham Palace, and Nash was employed to design the three-house terrace in his signature, rigidly Classical style: clad in stucco, with an imposing Corinthian portico, balconies, pediments, and Attic parapet, over a podium with squat Doric columns.[34]

Nash's most defining association was with the Prince Regent, who was his greatest patron. The most enduring legacy of this relationship is Buckingham Palace, which was transformed from the modest Buckingham House of George III's reign into a grand Neoclassical palace to Nash's designs. Beginning in 1825, Nash extended the existing house westwards and added two flanking wings, which created an open forecourt, or Cour d'honneur, facing St. James's Park.[35] The style is remarkably similar to Nash's terraces being constructed on the edges of Regents Park, with the exception that the Palace was built in golden-hued Bath stone instead of stucco-faced brick.[36] The front façade of the main block features a two-story porch of Doric columns on the bottom, tall fluted Corinthian columns above, with a pediment topped by statuary and adorned in high-relief sculpture.[37] All the hallmarks of Regency Neoclassicism also appear, including an encompassing frieze with vegetative scrollwork made of Coade stone, balconies accessible from the first floor, and an attic with figural sculptures using the Elgin Marbles as their model. The west front overlooking the main garden features a bay window at its center, with a long terrace with balustrades and large Classical urns made of Coade stone.[38] Preceding the forecourt was a monumental Roman arch, modelled on the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel in Paris, which currently stands as the Marble Arch on the northeastern edge of Hyde Park.[39] The addition of the East Wing during the early reign of Queen Victoria enclosed the forecourt and created the frontage of Buckingham Palace known ever since, but the bulk of the Palace exterior remains from Nash's Regency additions, particularly the long garden front on the west side.

Contemporaneous to Nash's building work in Regents Park and St. James', the development of Belgravia further west offers the most uniform and extensive example of Regency architecture in London in the form of Belgrave, Eaton, Wilton Crescent and Chester Squares. An ultra-exclusive housing development built on a formerly rural swathe of land on the Grosvenor Estate, building was entrusted to Thomas Cubitt and began in 1825 with Belgrave Square, with the three main squares completed and occupied by the 1840s.[40] Like Nash, Cubitt designed elegant Classical terraces, some more austere than others, this time around traditional garden squares. All were covered in white-painted stucco with the entrance to each house featuring projecting Doric porches supporting first floor balconies with tall pedimented windows, and attics resting on cornice-work in the Greek manner.[41][42]

Victorian Architecture

.jpg)

Buildings from the Victorian era (1837-1901) and their diverse range of forms and ornamentation are the single largest group from any architectural period in London.[43] The Victorian era saw unprecedented urbanization and growth in London, coinciding with Britain's ascendancy in the world economy and London's global preeminence as the first metropolis of the modern world. As the political centre of the world's largest Empire and the trading and financial hub of the Pax Britannica, London's architecture reflects the extraordinary affluence of the period.

As London grew during the 19th century, the compact, close proximity of different social classes which had characterized life in the City of London transformed into a taste for specially developed suburbs for specific classes of the population. This is reflected in the style of domestic and commercial architecture. Donald Olsen wrote in The Growth of Victorian London that "the shift from multi-purpose to single-purpose neighborhoods reflected the pervasive move towards professionalization and specialization in all aspects of nineteenth-century thought and activity."[44]

The single most pervasive style of architecture was Neo-Gothic, also called Gothic Revival, embodied by the new Palace of Westminster built to designs by Charles Barry between 1840 and 1876.[45] Gothic architecture embodied "the influence of London's past" and coincided with Romanticism, a cultural movement which glorified all things Medieval, from literature and painting to music and architecture.[46] The evangelism prevalent in mid-century Britain was also a factor in favoring Gothic Revival, which referenced great English cathedrals like Ely and Salisbury.[47] The leading proponents of Gothic Revival were Augustus Pugin, entrusted with the interior design of the Palace of Westminster, and John Ruskin, a highly influential art critic.[48]

Hallmarks of Gothic architecture are tracery, a form of delicate, web-like ornamentation for windows, parapets, and all external ornamentation. Symmetry of lines, pointed arches, spires, and steep roofs are other characteristics.[49] Cast-iron, and from the mid 19th-century mild steel were used in Gothic revival iron structures like Blackfriars Bridge (1869) and St. Pancras railway station (1868).[50] Other significant buildings built in Gothic Revival are the Royal Courts of Justice (1882), the Midland Grand Hotel (1876) adjoining St. Pancras Station, Liverpool Street station (1875) All Saints church in Fitzrovia, and the Albert Memorial (1872) in Kensington Gardens.[51] Even the suburbs were built in derivative Gothic Revival styles, called "Wimbledon Gothic".[52]

Iron was not just decorative, but advancements in engineering enabled its use to build the first iron-framed structures in history. Iron beams afforded unprecedented span and height in new buildings, with the added advantage of being fireproof. The greatest embodiment of iron's possibilities were found in Joseph Paxton's The Crystal Palace, a 990,000 square foot exhibition hall made of cast-iron and plate glass which opened in 1851.[53] Before that, iron was already being used to gird the roofs of the King's Library in the British Museum, built between 1823–27, the Reform Club (1837–41), Travellers Club (1832), and the new Palace of Westminster.[54] The technological advancements pioneered with the Crystal Palace would be applied to the building of London's great railway termini in the latter half of the century: St. Pancras, Liverpool Street station, Paddington, King's Cross, and Victoria.[55] King's Cross was a relative latecomer; built in 1851 to support incoming traffic for the Crystal Palace exhibition, its arched glass terminal sheds (each 71 ft. wide) were reinforced with laminated wooden ribs which were replaced in the 1870s with cast iron.[56] London Paddington had already set the model for train stations built with iron support piers and framework, when it was completed in 1854 to the designs of the greatest of Victorian engineers, Isambard Kingdom Brunel.[57]

.jpg)

Victorian architecture was not confined to Gothic Revival but was characterized by its diversity and the great variety of historic styles it referenced. These included Renaissance Revival, Queen Anne Revival (popular in the late 19th century), Moorish Revival, and Neoclassicism. New styles, not based on revivals of historic architecture, were also avidly adopted, like that of the Second Empire copied from France in the 1870s.[58]

From the 1860s, terracotta began to be used as a decorative appliqué for new constructions, but its true popularity came between 1880 and 1900.[59] During this period, entire buildings were covered in elaborately moulded terra cotta tiles, like the Natural History Museum (1880), the rebuilt Harrods department store building (1895-1905), and the Prudential Assurance Building on High Holborn (1885-1901).[60] Terracotta was very advantageous in that it was colorful and, because it was kiln-fired, it did not absorb the heavy air pollution of Victorian London, unlike brick and stone. As Ben Weinreb described terracotta's usage: "it found the greatest favour on the brasher, self-advertising types of building such as shops, theatres, pubs and the larger City offices."[61]

Despite the explosive growth of Victorian London and the impressive scale of much of the building that had taken place, by the 1880s and 1890s there was an increasing belief that London's urban fabric was inferior to other European cities and unsuitable for the capital of the world's largest empire. There was little coherent urban planning in London during the Victorian era, apart from major infrastructure projects like the Thames Embankment or Tower Bridge. Critics compared London to cities like Paris or Vienna, both of which had experienced the intervention of the state and large scale demolition to create a more regularized arrangement, broad boulevards, panoramas and architectural uniformity. London was "visibly the bastion of private property rights", which accounted for the eclecticism of its buildings.[62]

Edwardian Architecture (1901-1914)

The dawn of the 20th century and the death of Queen Victoria (1901) saw a shift in architectural taste and a reaction against Victorianism. The popularity of Neoclassicism, dormant during the latter half of the 19th century, revived with the new styles of Beaux-Arts and Edwardian Baroque, also called the "Grand Manner".[63] Neoclassical architecture suited an "Imperial City" like London because it evoked the grandeur of the Roman Empire and was monumental in scale. Trademarks include rusticated stonework, banded columns or quoins of alternating smooth and rusticated stonework, exaggerated voussoirs for arched openings, free-standing columns or semi-engaged pilasters with either Corinthian or Ionic capitals, and domed roofs with accompanying corner domes or elaborate cupolas.[64] In adopting such styles, British architects evoked hallowed English baroque structures like St. Paul's Cathedral and Inigo Jones' Banqueting House.[65] Municipal, government, and ecclesiastical buildings of the years 1900-1914 avidly adopted Neo-Baroque architecture for large construction works like the Old Bailey (1902), County Hall (begun in 1911), the Port of London Authority building (begun 1912),[66] the War Office (1906), and Methodist Central Hall (1911).

Some of the most impressive commercial buildings constructed during the Edwardian era include the famous Ritz Hotel on Piccadilly (1906), Norman Shaw's Piccadilly Hotel (1905), Selfridges Department Store (1909), and Whiteleys department store (1911). All of these buildings were built in variations of Neoclassicism: Beaux-Arts, Neo-Baroque, or Louis XVI. The firm of Mewès & Davis, partners who were alumni of the École des Beaux-Arts, specialized in 18th Century French architecture, specifically Louis XVI. This is evident in their two most famous projects, the Ritz Hotel and Inveresk House, the headquarters of the Morning Post, on Aldwych.[67][68]

The popularity of terracotta for exterior cladding waned in favor of glazed ceramic tiles known as faience. Some outstanding examples include the Strand Palace Hotel (1909) and Regent Palace Hotel (1914), both clad in cream-colored 'Marmo' tiles manufactured by Burmantofts Pottery, Michelin House (1911), and Debenham House (1907).[69]London Underground stations built during the Edwardian years, namely those on the Piccadilly Line and Bakerloo Line, all employ faience tile cladding designed by Leslie Green.[70] The signature feature of these stations is Oxblood red faience tiles for the station exteriors, ticket halls clad in green and white tiles, and platforms decorated in individualized color themes depending on the station.[71] Glazed tiles had the added advantage of being easy to clean and being impervious to London's polluted atmosphere.

The two most important architectural accomplishments undertaken in London during the Edwardian years were the building of Kingsway and the creation of an enormous processional route stretching from Buckingham Palace to St. Paul's Cathedral. A grand parade route, a common feature of European cities like Paris, Vienna, and Berlin, was felt to be sadly lacking in London.[72] To accomplish this a group of buildings standing between The Mall and Trafalgar Square were demolished and replaced with the grand Neo-Baroque edifice of Admiralty Arch. This created one grand east-west parade route encompassing Buckingham Palace, Trafalgar Square via Admiralty Arch, then connecting with the newly widened Strand, and thence to Fleet Street.[73] The 82 ft. high Victoria Memorial was erected in front of Buckingham Palace (unveiled in 1911) and encircled by four ceremonial gates dedicated to the British dominions: Canada Gate, Australia Gate, South and West Africa Gates.[74] In 1913 the decaying Caen stone on the façade of Buckingham Palace, which was blackened by pollution and deteriorating, was replaced with a more impressive facing of Portland stone.[75][76]

Kingsway, a 100 foot wide boulevard with underground tram tunnel stretch north-south from the Strand to High Holborn, was the culmination of a slum clearance and urban regeneration project initiated by the Strand Improvement Bill of 1899.[77] This involved the clearance of a notorious Holborn slum known as Clare Market, between Covent Garden and Lincoln's Inn Fields.[78] The demolition destroyed buildings dating back to the Elizabethan era, some of the few to have survived the Great Fire of London. In its place Kingsway and Aldwych were constructed, the latter a crescent-shaped road connecting the Strand to Kingsway. The north side of the Strand was demolished, allowing the street to be widened and more impressive and architecturally sound buildings to be constructed. Lining these grand new boulevards were impressive new theatres, hotels, and diplomatic commissions in imposing Neoclassical, Portland stone-clad designs. These new buildings included the headquarters of Britain's most important imperial possessions: India House, Australia House, with South Africa House built in the 1930s opposite Trafalgar Square. There were plans to demolish two churches along the Strand, St Mary le Strand and St Clement Danes, the latter designed by Sir Christopher Wren, because they were protruding into the street and causing traffic congestion. After public outcry the Strand was instead widened to circumvent the churches, creating 'islands' in the middle.[79]

Steel

In the first decade of the 20th century, the use of steel for reinforcing new buildings advanced tremendously.[80] Steel piers had been used in isolation to support the National Liberal Club (1886) and the rebuilt Harrods Department Store (1905). It was the extensions of 1904-5 for the Savoy Hotel which used steel framing for the whole construction, followed closely by the Ritz Hotel (1906); the latter gained the popular reputation for being the first building in London to be steel-framed.[81] The abundance of domes in the Edwardian period is also attributable to steel girders, which made large domes lighter, cheaper to build, and much easier to engineer.[82]

Selfridges on Oxford Street, modelled after American-style department stores, was the true watershed because its size was unprecedented by British standards and far exceeded existing building regulations. To gain planning approval, Selfridge's architect Sven Bylander (the engineer responsible for the Ritz) worked closely with the London County Council to update the LCC's woefully outdated regulations on the use of steel, dating back to 1844.[83][84] In 1907 he gained approval for his plans, and by 1909 when Selfridges opened the LCC passed the LCC (General Powers) Act, also known as the Steel Act, which provided comprehensive guidelines for steel-framed buildings and a more streamlined process for gaining planning permission.[85][86] By this point, steel-reinforcement was de rigueur in any sizable public or commercial building, as seen in the new buildings proliferating along Aldwych and Kingsway.

Art Deco & Interwar Architecture (1919-1939)

.jpg)

London in the years following the conclusion of World War I saw a glut of outstanding building projects begun prior to 1914 reach their long-delayed completion. The somber mood and straitened financial circumstances of interwar Britain made the flamboyant Neo-Baroque style no longer suitable for new architecture. Instead, British architects turned back to the austere, clean lines of Georgian Architecture for inspiration.[87] Consequently, Neo-Georgian was the preferred style for municipal and government architecture well into the 1960s.[88] The sale and demolition of many of London's grandest aristocratic houses gave rise to some of the largest private building projects of the interwar period, built to Art Deco or Neo-Georgian designs. These include The Dorchester (Art Deco) and the Grosvenor House Hotel (Neo-Georgian) on Park Lane, both constructed on the sites of grand London houses of the same names. Many buildings clustered around Georgian squares in central London were demolished and replaced, ironically enough, with Neo-Georgian edifices in near identical styles but to greater size. Grosvenor Square, the most exclusive of London's squares, saw the demolition of original Georgian buildings and construction in favor of the uniform Neo-Georgian townhouses which currently encircle the square on the north, east and south sides.[89] In St. James's Square several buildings were demolished and rebuilt in the Neo-Georgian style, the most famous of which was Norfolk House.[90]

Neo-Classicism remained popular for large building projects in London, but it dispatched with the heavy ornamentation and bold proportions of the Baroque. It remained the preferred style for banks, financial houses, and associations seeking to communicate prestige and authority. Perhaps the most prominent example of interwar Neoclassicism is the rebuilt Bank of England in the City of London, designed by Sir Herbert Baker and built between 1921 and 1937.[91][92] Neoclassicism cannot be mentioned without referring to the single most influential proponent of this style in interwar Britain, Sir Edwin Lutyens. His distinctive form of Neoclassicism can be seen in London with The Cenotaph,[93] the monolithic, streamlined war memorial built of Portland stone on Whitehall, the Midland Bank building[94] and Britannic House in Finsbury Circus, both in the City of London, and the headquarters of the British Medical Association in Tavistock Square, Bloomsbury.[95] In Westminster, a fine example of interwar Neoclassicism is Devonshire House, an office building constructed between 1924-26 on the site of the former London house of the Dukes of Devonshire.[96] Classicism of this style was almost exclusively executed in the ever-popular Portland stone.

Art Deco

Existing alongside the more prevalent Neo-Georgian and Neoclassical forms of architecture used in the capital in the 1920s and 1930s, Art Deco was nonetheless an extremely popular style from approximately 1925 to the latter 1930s.[97] The true stimulus was the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts held in Paris, where Art Deco had been developed roughly 20 years earlier. London, alongside New York City and Paris, became an innovative and experimental ground for Art Deco architecture. Art Deco architecture is defined by clean lines, curves, geometric patterns, bold color, and elaborate, stylized sculptural accents.[98] Art Deco was adopted most enthusiastically by "modern" businesses or those seeking to advertise their modernity and forward-thinking attitude. These include cinemas, media headquarters, airports, swimming pools, factories, and power stations (i.e. Battersea Power Station). It was a flashy, luxurious style, so it was also well adapted for department stores (i.e. Simpsons of Piccadilly), theatres, hotels, and apartment blocks.[99]

Two of London's finest examples of Art Deco architecture stand on Fleet Street: the Daily Telegraph building (1928) and the Daily Express Building.[100] The façade of the latter is, unusual for the time, composed entirely of glass, vitrolite and chromium, which stood out boldly amongst the stone and brick architecture of Fleet Street. The use of industrial, sleek materials like these was more common in Deco buildings in New York City than it was in London: Portland stone remained overwhelmingly the material of choice. Not coincidentally, another media headquarters, the BBC's Broadcasting House on Portland Place, was built in the traditional Portland stone with outstanding figural sculptures by Eric Gill.[101] Ideal House (1929), is highly unique in combining Art Deco with Egyptian motifs, on a façade clad in shiny black granite.[102] Another Art Deco/Egyptian synthesis is the Carreras Cigarette Factory in Mornington Crescent.[103]

The erection of ultra-modern Deco buildings often came at the expense of older architectural gems, some irreplaceable. Along the Embankment two large Deco buildings were constructed which continue to dominate London's riverfront profile. The elegant Neoclassical Adelphi Buildings, designed by Robert and John Adam and built between 1768–71, were demolished to build the New Adelphi office building in the 1930s.[104] Adjacent to the Adelphi, the grand Hotel Cecil (1896) was demolished to make way for Shell Mex House (1931), a 190 ft. high Art Deco office building which features London's largest clock.[105]

The 19-story Senate House, headquarters of the University of London, is the tallest Art Deco structure in London and was one of the tallest buildings in London when finished in 1937.[106] It elicited, and continues to elicit, much criticism because it stands so tall and obtrusively amongst the modest Georgian squares of Bloomsbury. Evelyn Waugh described it as a "vast bulk...insulting the autumnal sky", while more recent critics have called it Stalinesque or reminiscent of the Third Reich.[107][108] This association with totalitarian architecture was reinforced by the wartime rumor that Hitler wanted Senate House for his London headquarters upon conquering Britain, and therefore ordered Luftwaffe bombers to avoid it during The Blitz.[109]

Brutalist architecture in London

Following The Blitz London's urban fabric and infrastructure was devastated by continuous aerial bombardment by the Luftwaffe with almost 20,000 civilians killed and more than a million houses destroyed or damaged.[110] Hundreds of thousands of citizens had been evacuated to safer areas, the reconstruction of a habitable urban environment became a national emergency.

The re-housing crisis aligned with post-War optimism manifested in the Welfare State afforded an opportunity and a duty for the architectural profession to rebuild the shattered capital. The internationally influential urban planner Sir Patrick Abercrombie established the 1943 County of London Plan which set out redevelopment according to modernist principles of zoning and de-densification of historic urban areas. The 1951 Festival of Britain held on London's South Bank became an important cultural landmark in sharing and disseminating optimism for future progress – the Royal Festival Hall built 1948–51 and later South Bank Centre including Hayward Gallery(1968), Queen Elizabeth Hall/ Purcell Room (1967) and the Royal National Theatre (1976) remain as significant architectural and cultural legacies of the era.

Accelerating pre-War trends, overcrowded urban populations were relocated to new suburban developments allowing inner city areas to be reconstructed - the Golden Lane Estate , later followed by the Barbican by Chamberlin, Powell and Bon are regarded as a case book examples of urban reconstruction of the period in the City of London, where just 5,324 local residents had remained by the end of the war.[111] London had also attracted a select group of important European modernists, some as refugees from Nazism, and the post war era presented opportunities for many to express their unique vision for modernism. Important European architects of the era include Berthold Lubetkin and Erno Goldfinger who employed and trained architects on modernist social housing such as the Dorset Estate of 1957, Alexander Fleming House 1962-64, Balfron Tower of 1963 and Trellick Tower of 1966, as well as Keeling House by Denys Lasdun in 1957.

International movements in architecture and urban planning were reflected in the new developments with separation of motor transportation and industrial and commercial uses from living areas according to the prevailing orthodoxies of CIAM.[112] High-rise residential developments of Council housing in London were above all else influenced by le Corbusier's Unité d'habitation (aka Cité Radieuse('Radiant City')of 1947-52.[113] The architecture of post war modernism was informed by ideals of technological progress and social progress through egalitarianism - this was expressed by humanistic repetition of forms and use of the modernist material par excellence - Béton brut[114] or 'raw concrete'. Significant Council Housing works in London include the Brunswick Centre 1967-72 by Patrick Hodgkinson the Alexandra Road Estate 1972-78 by Neave Brown of the Camden Council architects department.

The British exponent of the internationalist movement was headed by Alison and Peter Smithson, originally as part of Team 10 they went on to design Robin Hood Gardens 1972 in Bow and the Economist Building[115] (1962-4) in Mayfair regarded by architects as some of the very finest works of British New Brutalism.

Many schools, residential housing and public buildings were built over the period, however the failure of some the modernist ideals coupled with poor quality of construction and poor maintenance by building owners has resulted in a somewhat negative popular perception of the architecture of the era; this is however being transformed and expressed in the enduring value and prestige of refurbished developments such as the Barbican, Trellick Tower and Balfron Tower regarded by many as architectural 'icons' of a distant era of confidently heroic progressive social constructivism and highly sought-after places of residence.

Skyscrapers and structures

London has a growing number of Skyscrapers with twelve buildings under construction to rise above 100 metres (328 ft) with a further 44 approved. The Shard London Bridge (topped out in Spring 2012) is the tallest building in the European Union being 310 metres (1,016 ft) high.

The Tower of London

The Tower of London

Sep2000.jpg)

The London Eye

The London Eye The British Museum

The British Museum 10 Downing Street - The "most famous front door in the world".

10 Downing Street - The "most famous front door in the world". ArcelorMittal Orbit in the Olympic Park

ArcelorMittal Orbit in the Olympic Park Multi-award-winning BedZED zero energy development in the London Borough of Sutton

Multi-award-winning BedZED zero energy development in the London Borough of Sutton

See also

References

- Marianne Butler, London Architecture, metropublications, 2006

- Billings, Henrietta, Brutalist London Map, Blue Crow Media, 2015

- Notes

- ↑ "London skyscrapers". Dezeen. Retrieved 2017-12-16.

- ↑ "The London skyline debate | Cities". The Guardian. Retrieved 2017-12-16.

- ↑ "Shard London Bridge, London - SkyscraperPage.com". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ↑ "List and details of the tallest buildings in the world". infoplease.com. Infoplease Encyclopedia. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ↑ "A vertical city". The-Shard.com. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ↑ https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/architecture_paper_wp86.pdf

- ↑ Dilley, James (2012-02-23). "Mesolithic and Bronze Age archaeology on the Thames Foreshore at Vauxhall" (pdf). ancientcraft.co.uk. Retrieved 2017-12-16.

- ↑ "Thames Discovery Programme". www.thamesdiscovery.org. Retrieved 2017-12-09.

- ↑ Lady Charlotte Schreiber. "The Story of LLudd & LLeuellys". The Mabinogion.

- ↑ London Archaeology; Vol 15 Spring 2018

- ↑ "The Remains of London's Roman Basilica and Forum". Historic-uk.com. Retrieved 2017-12-16.

- ↑ London Archaeology, Ibid

- ↑ https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/architecture/roman-eagle-rises-again-in-london-after-2000-years-8911721.html

- ↑ "Billingsgate Roman House & Baths". City of London. Retrieved 2017-12-16.

- ↑ "London Stone in seven strange myths". Museumoflondon.org.uk. 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2017-12-16.

- ↑ "Palladianism | architectural style". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2017-12-16.

- ↑

- ↑ "Domestic Architecture 1700 to 1960". Fet.uwe.ac.uk. Retrieved 2017-12-16.

- ↑ https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/culture/step-back-into-the-spitalfields-of-huguenots/8646533.article

- ↑ http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vols33-4/pp238-246

- ↑ Sir John Summerson (1945). Georgian London. p. 135.

- ↑ "Architectural Style: Georgian Architecture (1740-1830)". buildinghistory.org. Retrieved 2018-07-12.

- ↑ "Style Guide: Regency Classicism". vam.ac.uk. 2016. Retrieved 2018-09-22.

- ↑ Matthew Weinreb (1999). London: Portrait of a City. Phaidon. p. 218.

- ↑ Matthew Weinreb (1999). London: Portrait of a City. Phaidon. p. 218.

- ↑ "John Nash: Biography of English Neoclassical Regency Architect". visual-arts-cork.com. Retrieved 2018-07-12.

- ↑ James Stourton (2012). Great Houses of London. Frances Lincoln Ltd. p. 242–246.

- ↑ Matthew Weinreb (1999). London: Portrait of a City. Phaidon. p. 49.

- ↑ James Stourton (2012). Great Houses of London. Frances Lincoln Ltd. p. 242–246.

- ↑ Arnold, Dana. "Decimus Burton". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- ↑ "Style Guide: Regency Classicism". vam.ac.uk. Retrieved 2018-07-12.

- ↑ "The Athenaeum Club, Pall Mall". Retrieved 2018-07-12.

- ↑ James Stourton (2012). Great Houses of London. Frances Lincoln Ltd. p. 256.

- ↑ Gater, G. H.; Hiorns, F. R., eds. (1940). "Chapter 9: Carlton House Terrace and Carlton Gardens". Survey of London: Volume 20, St Martin-in-The-Fields, Pt III: Trafalgar Square & Neighbourhood. London: London County Council. pp. 77–87. Retrieved 12 July 2018 – via British History Online.

- ↑ Jonathan Marsden (2011). Buckingham Palace. Royal Collection Publications. p. 18–20.

- ↑ Historic England. "Buckingham Palace List Entry Summary". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 2018-07-13.

- ↑ Historic England. "Buckingham Palace List Entry Summary". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 2018-07-13.

- ↑ Historic England. "Buckingham Palace List Entry Summary". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 2018-07-13.

- ↑ Jonathan Marsden (2011). Buckingham Palace. Royal Collection Publications. p. 27.

- ↑ James Stourton (2012). Great Houses of London. Frances Lincoln Ltd. p. 169.

- ↑ "The Architecture of the Estate: The Reign of the Cundys". Survey of London Vol. 39, the Grosvenor Estate in Mayfair (Part 1). 1977. Retrieved 2018-07-12.

- ↑ Historic England. "The Grosvenor Estate: Belgrave Square". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 2018-07-12.

- ↑ Christopher Winn (2018-03-07). "The unsung buildings that bring Victorian London to life". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ↑ Peter Ackroyd (2000). London: The Biography. p. 516.

- ↑ Peter Ackroyd (2000). London: The Biography. p. 570.

- ↑ Sandra Lawrence (2018-01-30). "Around Town: London's Dramatic Victorian Architecture". britishheritage.com. Retrieved 2018-04-22.

- ↑ Kathryn Hughes (2011-09-11). "Victorian buildings: architecture and morality". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-04-22.

- ↑ Kathryn Hughes (2011-09-11). "Victorian buildings: architecture and morality". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-04-22.

- ↑ "Style Guide: Gothic Revival". vam.ac.uk. Retrieved 2018-04-21.

- ↑ Ben Weinreb (1999). London: Portrait of a City. Phaidon. p. 20–21.

- ↑ "Style Guide: Gothic Revival". vam.ac.uk. Retrieved 2018-04-21.

- ↑ Peter Ackroyd (2000). London: The Biography. p. 570.

- ↑ David Lancaster (1988-10-01). "History of the Crystal Palace". crystalpalacefoundation.org.uk. Retrieved 2018-04-21.

- ↑ Ben Weinreb (1999). London: Portrait of a City. Phaidon. p. 59.

- ↑ Alan Jackson (1984). London's Termini. p. 396.

- ↑ Christopher Winn (2018-03-07). "The unsung buildings that bring Victorian London to life". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ↑ Alan Jackson (1984). London's Termini. p. 308.

- ↑ Kathryn Hughes (2011-09-11). "Victorian buildings: architecture and morality". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-04-22.

- ↑ Ben Weinreb (1999). London: Portrait of a City. Phaidon. p. 119.

- ↑ Ben Weinreb (1999). London: Portrait of a City. Phaidon. p. 119.

- ↑ Ben Weinreb (1999). London: Portrait of a City. Phaidon. p. 119.

- ↑ Clive Aslet (2015). The Age of Empire. Aurum Press. p. 341.

- ↑ Thom Gorst (1995). The Buildings Around Us. Chapman & Hall. p. 63.

- ↑ Clive Aslet (2015). The Age of Empire. Aurum Press. p. 42.

- ↑ Leo Benedictus (2011-09-10). "Edwardian architecture: Five of the best examples". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-04-01.

- ↑ "Former Port of London Authority Building". Historic England. Retrieved 2018-05-01.

- ↑ Clive Aslet (2015). The Age of Empire. Aurum Press. p. 45.

- ↑ "INVERESK HOUSE Historic Listing". Historic England. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

- ↑ Ben Weinreb (2000). London Portrait of a City. Phaidon. p. 138.

- ↑ John Bull (2010-01-01). "The Man Who Painted London Red". londonreconnections.com. Retrieved 2018-05-01.

- ↑ Mark Byrnes (2015-12-09). "A Design Guide to London's Underground Stations". citylab.com. Retrieved 2018-05-01.

- ↑ Jonathan Marsden (2011). Buckingham Palace Official Souvenir Guide. p. 36.

- ↑ Clive Aslet (2015). The Age of Empire. Aurum Press. p. 341.

- ↑ "The Queen Victoria Memorial". royalparks.org.uk. Retrieved 2018-05-01.

- ↑ Jonathan Marsden (2011). Buckingham Palace Official Souvenir Guide. p. 36.

- ↑ Thom Gorst (1995). The Buildings Around Us. Chapman & Hall. p. 39–40.

- ↑ Clive Aslet (2015). The Age of Empire. Aurum Press. p. 36.

- ↑ Ed Glinert (2003). The London Compendium. p. 114–15.

- ↑ Clive Aslet (2015). The Age of Empire. Aurum Press. p. 36.

- ↑ Historic England (2014-04-08). "Victorian & Edwardian London at the Dawn of the Steel Age". heritagecalling.com. Retrieved 2018-05-02.

- ↑ Alastair A. Jackson (1998). The Development of Steel-Framed Buildings in Britain, 1880-1905 (PDF). Construction History Vol. 14. p. 21–37.

- ↑ Clive Aslet (2015). The Age of Empire. Aurum Press. p. 42.

- ↑ Kathryn A. Morrison (2003). English Shops & Shopping: An Architectural History.

- ↑ Alastair A. Jackson (1998). The Development of Steel-Framed Buildings in Britain, 1880-1905 (PDF). Construction History Vol. 14. p. 21–37.

- ↑ David Goodman (1999). The European Cities and Technology Reader: Industrial to Post-Industrial City. p. 172.

- ↑ Historic England (2014-04-08). "Victorian & Edwardian London at the Dawn of the Steel Age". heritagecalling.com. Retrieved 2018-05-02.

- ↑ Simon Thurley (2013-02-06). "Forwards and Backwards: Architecture in Interwar England". Gresham College. Retrieved 2018-05-21.

- ↑ Elizabeth McKellar (2016-09-30). "You Didn't Know it was Neo-Georgian". Historic England. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- ↑ Simon Thurley (2013-02-06). "Forwards and Backwards: Architecture in Interwar England". Gresham College. Retrieved 2018-05-21.

- ↑ "St. James's Square: No 31, Norfolk House". british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- ↑ "Bank of England Rebuilding (1933)". engineering-timeline.com. Retrieved 2018-05-21.

- ↑ "Bank of England List Entry". Historic England. Retrieved 2018-05-21.

- ↑ "Cenotaph, Whitehall, Westminster, Greater London". Historic England. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- ↑ Chris Leadbeater (2013-11-12). "Iconic London bank building (and former James Bond set) to be reworked as a hotel". Daily Mail. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- ↑ "Listing Entry Summary BMA House". Historic England. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- ↑ "Listing Entry Devonshire House". Historic England. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- ↑ Beau Peregoy (2016-12-17). "7 of the Best Art Deco Buildings in London". Architectural Digest. Retrieved 2018-04-20.

- ↑ Suzanne Waters. "Art Deco". Architecture.com. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- ↑ Suzanne Waters. "Art Deco". Architecture.com. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- ↑ Beau Peregoy (2016-12-17). "7 of the Best Art Deco Buildings in London". Architectural Digest. Retrieved 2018-04-20.

- ↑ Thibaud Hérem (2013). London Deco. Nobrow Press. p. 1.

- ↑ Thibaud Hérem (2013). London Deco. Nobrow Press. p. 2.

- ↑ Charlie Vernon (2015-08-06). "Exploring Art Deco in London". Senate House Library. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- ↑ Robert Clear (2017-01-13). "The Adelphi Story". Londonist. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- ↑ "Shell Mex House". britishlistedbuildings.co.uk. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- ↑ Charlie Vernon (2015-08-06). "Exploring Art Deco in London". Senate House Library. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- ↑ Simon Jenkins (2005-12-01). "It's time to knock down Hitler's headquarters and start again". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- ↑ Eitan Karol (Autumn–Winter 2008). "Naked and Unashamed: Charles Holden in Bloomsbury". The Institute of Historical Research. p. 6-7.

- ↑ Simon Jenkins (2005-12-01). "It's time to knock down Hitler's headquarters and start again". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- ↑ Richards 1954, p. 217.

- ↑ Billings, Henrietta (November 2015). Brutalist London Map. London: Blue Crow Media. ISBN 9780993193453.

- ↑ Modern Architecture: A Critical History (1980; revised 1985, 1992 and 2007) Kenneth Frampton

- ↑ https://www.dezeen.com/2014/09/15/le-corbusier-unite-d-habitation-cite-radieuse-marseille-brutalist-architecture/

- ↑ Raw Concrete: The Beauty of Brutalism, Barnabas Calder

- ↑ "{title}". Archived from the original on 2016-10-07. Retrieved 2018-01-07.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Architecture of London. |

- Architecture of London From Archiseek.com

- Architecture of London Projects from Design Architecture Limited

- Brutalist Architecture in London from Blue crow media

- Art Deco Architecture in London from Blue crow media