Royal Observatory, Greenwich

Royal Observatory, Greenwich. A time ball sits atop the Octagon Room. | |

| Alternative names |

Royal Greenwich Observatory |

|---|---|

| Observatory code |

000 |

| Location |

Greenwich, Royal Borough of Greenwich, United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 51°28′40″N 0°00′05″W / 51.4778°N 0.0014°WCoordinates: 51°28′40″N 0°00′05″W / 51.4778°N 0.0014°W |

| Website |

www |

| Telescopes |

Altazimuth Pavilion At The Royal Observatory |

Location of Royal Observatory, Greenwich | |

|

| |

The Royal Observatory, Greenwich (ROG;[1] known as the Old Royal Observatory from 1957 to 1998, when the working Royal Greenwich Observatory, RGO, moved from Greenwich to Herstmonceux) is an observatory situated on a hill in Greenwich Park, overlooking the River Thames. It played a major role in the history of astronomy and navigation, and is best known for the fact that the prime meridian passes through it, and thereby gave its name to Greenwich Mean Time. The ROG has the IAU observatory code of 000, the first in the list.[2] ROG, the National Maritime Museum, the Queen's House and Cutty Sark are collectively designated Royal Museums Greenwich.[1]

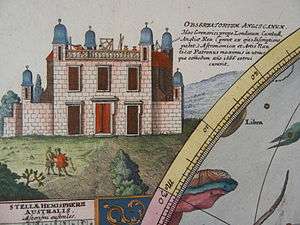

The observatory was commissioned in 1675 by King Charles II, with the foundation stone being laid on 10 August. The site was chosen by Sir Christopher Wren.[3] At that time the king also created the position of Astronomer Royal, to serve as the director of the observatory and to "apply himself with the most exact care and diligence to the rectifying of the tables of the motions of the heavens, and the places of the fixed stars, so as to find out the so much desired longitude of places for the perfecting of the art of navigation." He appointed John Flamsteed as the first Astronomer Royal. The building was completed in the summer of 1676.[4] The building was often called "Flamsteed House", in reference to its first occupant.

The scientific work of the observatory was relocated elsewhere in stages in the first half of the 20th century, and the Greenwich site is now maintained almost exclusively as a museum, although the AMAT telescope became operational for astronomical research in 2018.

History

Chronology

- 1675 – 22 June, Royal Observatory founded.

- 1675 – 10 August, construction began.

- 1714 Longitude Act established the Board of Longitude and Longitude rewards. The Astronomer Royal was, until the Board was dissolved in 1828, always an ex officio Commissioner of Longitude.

- 1767 Astronomer Royal Nevil Maskelyne began publication of the Nautical Almanac, based on observations made at the Observatory.

- 1818 Oversight of the Royal Observatory was transferred from the Board of Ordnance to the Board of Admiralty; at that time the observatory was charged with maintaining the Royal Navy's Marine chronometers.

- 1833 Daily time signals began, marked by dropping a Time ball.

- 1899 The New Physical Observatory (now known as the South Building) was completed.

- 1924 Hourly time signals (Greenwich Time Signal) from the Royal Observatory were first broadcast on 5 February.

- 1948 Office of the Astronomer Royal was moved to Herstmonceux.

- 1957 Royal Observatory completed its move to Herstmonceux, becoming the Royal Greenwich Observatory (RGO). The Greenwich site is renamed the Old Royal Observatory.

- 1990 RGO moved to Cambridge.

- 1998 RGO closed. Greenwich site is returned to its original name, the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, and is made part of the National Maritime Museum.

- 2011 The Greenwich museums, including the ROG, become collectively the Royal Museums Greenwich.

Site

There had been significant buildings on this land since the reign of William I.[5] Greenwich Palace, on the site of the present-day Maritime Museum, was the birthplace of both Henry VIII and his daughters Mary I and Elizabeth I; the Tudors used Greenwich Castle, which stood on the hilltop that the Observatory presently occupies, as a hunting lodge. Greenwich Castle was reportedly a favourite place for Henry VIII to house his mistresses, so that he could easily travel from the Palace to see them.[6]

Establishment

The establishment of a Royal Observatory was proposed in 1674 by Sir Jonas Moore who, in his role as Surveyor General at the Ordnance Office, persuaded King Charles II to create the observatory, with John Flamsteed installed as its director.[7] The Ordnance Office was given responsibility for building the Observatory, with Moore providing the key instruments and equipment for the observatory at his own personal cost. Flamsteed House, the original part of the Observatory, was designed by Sir Christopher Wren, probably assisted by Robert Hooke, and was the first purpose-built scientific research facility in Britain. It was built for a cost of £520 (£20 over budget) out of largely recycled materials on the foundations of Duke Humphrey's Tower, the forerunner of Greenwich Castle, which resulted in the alignment being 13 degrees away from true North, somewhat to Flamsteed's chagrin.

The original observatory at first housed the scientific instruments to be used by Flamsteed in his work on stellar tables, and over time also incorporated additional responsibilities such as marking the official time of day, and housing Her Majesty's Nautical Almanac Office.

Moore donated two clocks, built by Thomas Tompion, which were installed in the 20 foot high Octagon Room, the principal room of the building. They were of unusual design, each with a pendulum 13 feet (3.96 metres) in length mounted above the clock face, giving a period of four seconds and an accuracy, then unparalleled, of seven seconds per day.

Greenwich Meridian

British astronomers have long used the Royal Observatory as a basis for measurement. Four separate meridians have passed through the buildings, defined by successive instruments.[8] The basis of longitude, the meridian that passes through the Airy transit circle, first used in 1851, was adopted as the world's Prime Meridian at the International Meridian Conference on 22 October 1884 (voting took place on 13 October).[9] Subsequently, nations across the world used it as their standard for mapping and timekeeping. The Prime Meridian was marked by a brass (later replaced by stainless steel) strip in the Observatory's courtyard once the buildings became a museum in 1960, and, since 16 December 1999, has been marked by a powerful green laser shining north across the London night sky.

Since the first triangulation of Great Britain in the period 1783–1853, Ordnance Survey maps have been based on an earlier version of the Greenwich meridian, defined by the transit instrument of James Bradley. When the Airy circle (5.79 m to the east) became the reference for the meridian, the difference resulting from the change was considered small enough to be neglected. When a new triangulation was done between 1936 and 1962, scientists determined that in the Ordnance Survey system the longitude of the international Greenwich meridian was not 0° but 0°00'00.417" (about 8 m) East.[10] Besides the change of the reference line, imperfections of the surveying system added another discrepancy to the definition of the origin, so that the Bradley line itself is now 0°00'00.12" East of the Ordnance Survey Zero Meridian (about 2.3m).[11]

This old astronomical prime meridian has been replaced by a more precise prime meridian. When Greenwich was an active observatory, geographical coordinates were referred to a local oblate spheroid called a datum known as a geoid, whose surface closely matched local mean sea level. Several datums were in use around the world, all using different spheroids, because mean sea level undulates by as much as 100 metres worldwide. Modern geodetic reference systems, such as the World Geodetic System and the International Terrestrial Reference Frame, use a single oblate spheroid, fixed to the Earth's gravitational centre. The shift from several local spheroids to one worldwide spheroid caused all geographical coordinates to shift by many metres, sometimes as much as several hundred metres. The Prime Meridian of these modern reference systems is 102.5 metres east of the Greenwich astronomical meridian represented by the stainless steel strip, which is now 5.31 arcseconds West. The modern location of the Airy Transit is 51°28′40.1″N 0°0′5.3″W / 51.477806°N 0.001472°W[12]

International time from the end of the 19th century until UT1 was based on Simon Newcomb's equations, giving a mean sun about 0.18 seconds behind UT1 (the equivalent of 2.7 arcseconds) as of 2013; it coincided in 2013 with a meridian halfway between Airy's circle and the IERS origin: 51°28′40.1247″N 0°0′2.61″W / 51.477812417°N 0.0007250°W.[13]

Greenwich Mean Time and the time ball

Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) was until 1954 based on celestial observations made at Greenwich, and later on observations made at other observatories. GMT was formally renamed as Universal Time in 1935, but is still commonly referred to as GMT. It is now calculated from observations of extra-galactic radio sources.

To help mariners at the port and others in line of sight of the observatory to synchronise their clocks to GMT, Astronomer Royal John Pond installed a very visible time ball that drops precisely at 1 p.m. (13:00) every day atop the observatory in 1833. Initially it was dropped by an operator; from 1852 it was released automatically via an electric impulse from the Shepherd Master Clock.[14] The ball is still dropped daily at 13:00 (GMT in winter, BST in summer).[15]

Bomb attack of 1894

The Observatory underwent an attempted bombing on 15 February 1894. This was possibly the first "international terrorist" incident in Britain. The bomb was accidentally detonated while being held by 26-year-old French anarchist Martial Bourdin in Greenwich Park, near the Observatory building. Bourdin died about 30 minutes later. It is not known why he chose the observatory, or whether the detonation was intended to occur elsewhere. Novelist Joseph Conrad used the incident in his novel The Secret Agent.[16]

Early 20th century

During most of the twentieth century, the Royal Greenwich Observatory was not at Greenwich. The last time that all departments were there was 1924: in that year electrification of the railways affected the readings of the Magnetic and Meteorological Departments, and the Magnetic Observatory moved to Abinger. Prior to this, the observatory had had to insist that the electric trams in the vicinity could not use an earth return for the traction current.[19]

After the onset of World War II in 1939, many departments were temporarily evacuated out of range of German bombers, to Abinger, Bradford on Avon, Bristol,[20] and Bath,[21] and activities in Greenwich were reduced to the bare minimum.

On 15 October 1940, during the Blitz, the Courtyard gates were destroyed by a direct bomb hit. The wall above the Gate Clock collapsed, and the clock's dial was damaged. The damage was repaired after the war.[22]

Herstmonceux Castle

After the Second World War, in 1947, the decision was made to move to Herstmonceux Castle[23] and 320 adjacent acres (1.3 km²), 70 km south-southeast of Greenwich near Hailsham in East Sussex, due to light pollution in London. The Observatory was officially known as The Royal Greenwich Observatory, Herstmonceux. Although the Astronomer Royal Harold Spencer Jones moved to the castle in 1948, the scientific staff did not move until the observatory buildings were completed, in 1957. Shortly thereafter, other previously dispersed departments were reintegrated at Herstmonceux.

The Isaac Newton Telescope was built at Herstmonceux in 1967, but was moved to Roque de los Muchachos Observatory in Spain's Canary Islands in 1979. In 1990 the RGO moved again, to Cambridge.[24] Following a decision of the Particle Physics and Astronomy Research Council, it closed in 1998. Her Majesty's Nautical Almanac Office was transferred to the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, on the Harwell Science and Innovation Campus, Chilton, Oxfordshire after the closure. Other work went to the UK Astronomy Technology Centre in Edinburgh. The castle grounds became the home of the International Study Centre of Queen's University, Kingston, Canada and The Observatory Science Centre,[25] which is operated by an educational charity Science Project.

Greenwich site returns to active use

In 2018 the Annie Maunder Astrographic Telescope (AMAT) was installed at the ROG in Greenwich.[26][27] AMAT is a cluster of four separate instruments, to be used for astronomical research; it had achieved first light by June 2018[28]:

- A 14-inch reflector can take high resolution images of the sun, moon and planets.

- An instrument dedicated to observing the sun.

- An instrument with interchangeable filters to view distant nebulae at different optical wavelengths.

- A general-purpose telescope.

The telescopes and the works at the site required to operate them cost about £150,000, from grants, museum members and patrons, and public donations.

Observatory museum

The observatory buildings at Greenwich became a museum of astronomical and navigational tools, which is part of the Royal Museums Greenwich.[29] Notable exhibits include John Harrison's sea watch, the H4, which received a large reward from the Board of Longitude, and his three earlier marine timekeepers; all four are the property of the Ministry of Defence. Many additional horological artefacts are displayed, documenting the history of precision timekeeping for navigational and astronomical purposes, including the mid-20th-century Russian-made F.M. Fedchenko clock (the most accurate pendulum clock ever built in multiple copies). It also houses the astronomical instruments used to make meridian observations and the 28-inch equatorial Grubb refracting telescope of 1893, the largest of its kind in the UK. The Shepherd Clock outside the observatory gate is an early example of an electric slave clock.

In February 2005 a £16 million redevelopment comprising a new planetarium and additional display galleries and educational facilities was started; the ROG reopened on 25 May 2007 with the new 120-seat Peter Harrison Planetarium.[30]

References

- 1 2 Rebekah Higgitt (6 September 2012). "Royal Observatory Greenwich, London". BSHS Travel Guide - A Travel Guide to Scientific Sites. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ↑ "List of Observatory Codes". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ↑ "Greenwich and the Millennium". 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ↑ Robert Chambers, Book of Days

- ↑ John Timbs' Abbeys, Castles and Ancient Halls of England and Wales

- ↑ Hart, Kelly (2010), The Mistresses of Henry VIII, The History Press, p. 73, ISBN 978-0-7524-5496-2

- ↑ Willmoth, Frances (2004). "Moore, Sir Jonas (1617–1679)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/19137. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Dolan, Graham. "The Greenwich Meridian before the Airy Transit Circle". The Greenwich Meridian. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ↑ Howse, Derek (1997). Greenwich time and the longitude. London: Phillip Wilson. pp. 12, 137. ISBN 0-85667-468-0.

- ↑ Howse, Derek (1980). "Greenwich time and the discovery of the longitude". p. 171.

- ↑ Adams, Brian (1994). "Charles Close Society" (PDF). pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Malys, Stephen; Seago, John H.; Palvis, Nikolaos K.; Seidelmann, P. Kenneth; Kaplan, George H. (1 August 2015). "Why the Greenwich meridian moved". Journal of Geodesy. doi:10.1007/s00190-015-0844-6.

- ↑ Seago, John H.; Seidelmann, P. Kenneth. "The mean-solar-time origin of Universal Time and UTC" (PDF). Paper presented at the AAS/AIAA Spaceflight Mechanics Meeting, Kauai, HI, USA, March 2013. Reprinted from Advances in the Astronomical Sciences v. 148. pp. 1789, 1801, 1805. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 December 2013.

- ↑ "From The Royal Observatory: The Greenwich Time Ball". Londonist.com. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ↑ "Greenwich Time Ball".

- ↑ "Propaganda by Deed – the Greenwich Observatory Bomb of 1894". Archived from the original on 30 September 2007.

- ↑ Bennett, Keith (2004), Bucher, Jay L., ed., The Metrology Handbook, Milwaukee, WI: American Society for Quality Measurement, p. 8, ISBN 978-0-87389-620-7 .

- ↑ Walford, Edward (1878), Old and New London, VI .

- ↑ "Abinger Magnetic Observatory (1923-1957)". The Royal Observatory Greenwich. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ↑ "Bristol & Bradford on Avon (1939-1948)". The Royal Observatory Greenwich. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ↑ "Bath (1939-1949)". The Royal Observatory Greenwich. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ↑ "The Royal Observatory Greenwich - The Shepherd Gate Clock". Royal Observatory Greenwich. Retrieved 3 May 2017. A very detailed history of the Shepherd Gate Clock.

- ↑ "The Herstmonceux years... 1948-1990". The Royal Observatory Greenwich. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ↑ "A Personal History Of The Royal Greenwich Observatory at Herstmonceux Castle, 1948-1990 by G.A. Wilkins".

- ↑ the-observatory.org

- ↑ Ian Sample (25 June 2018). "Star attraction: Royal Observatory seeks volunteers to use new telescope". The Guardian.

- ↑ "Altazimuth Pavilion". Royal Observatory, Greenwich. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ↑ Kate Wilkinson (25 June 2018). "First Light: a new era for the Royal Observatory". Royal Observatory, Greenwich. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ↑ "Royal Museums Greenwich : Sea, Ships, Time and the Stars : RMG".

- ↑ "Press Release: Reopening of the new Royal Observatory, Greenwich". Royal Museums Greenwich. 27 June 2007. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

Further reading

- Greenwich Observatory: ... the Royal Observatory at Greenwich and Herstmonceux, 1675–1975. London: Taylor & Francis, 1975 3v. (Vol. 1. Origins and early history (1675–1835), by Eric G. Forbes. ISBN 0-85066-093-9; Vol. 2. Recent history (1836–1975), by A.J. Meadows. ISBN 0-85066-094-7; Vol. 3. The buildings and instruments by Derek Howse. ISBN 0-85066-095-5)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Royal Observatory, Greenwich. |

| Wikisource has the text of The New Student's Reference Work article Greenwich Observatory. |

- Royal Museums Greenwich (RMG) Web site - includes section on Royal Observatory Greenwich (ROG)

- Online catalogue of the Royal Greenwich Observatory Archives (held at Cambridge University Library)

- "Where the Earth's surface begins—and ends", Popular Mechanics, December 1930

- HM Nautical Almanac Office

- Aerial View of The Royal Observatory, Greenwich at Google Maps

- Castle in the sky – The story of the Royal Greenwich Observatory at Herstmonceux

- A Personal History of the Royal Greenwich Observatory at Herstmonceux Castle, 1948–1990 by George Wilkins, a former staff member

- The Observatory Science Centre

- Isaac Newton Group of Telescopes

- A pictorial catalogue of meridian markers