Methodist Central Hall, Westminster

| Methodist Central Hall | |

|---|---|

|

Front entrance | |

| Location | Westminster, London, SW1 |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Methodist Church of Great Britain |

| Architecture | |

| Style | |

| Groundbreaking | 1905 |

| Completed | 1911 |

| Specifications | |

| Capacity | 2,300 (Great Hall)[1] |

| Administration | |

| Circuit | Westminster |

| District | London |

| Clergy | |

| Minister(s) |

|

| Deacon(s) | Tina Saunders |

The Methodist Central Hall (also known as Central Hall Westminster) is a multi-purpose venue and tourist attraction in City of Westminster, London. It serves primarily as a Methodist church and a conference centre, but also as an art gallery and an office building (formerly as the headquarters of the Methodist Church of Great Britain until 2000). It contains twenty-two conference, meetings and seminar rooms, the largest being the Great Hall, which seats 2300.[2]

Central Hall occupies the corner of Tothill Street and Storeys Gate just off Victoria Street in London, near the junction with The Sanctuary next to the Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre and facing Westminster Abbey.

History

Methodist Central Hall was erected to mark the centenary of John Wesley's death. It was built in 1905–1911 on the site of the Royal Aquarium, Music Hall and Imperial Theatre, an entertainment complex that operated with varying success from 1876 to 1903.[3]

Methodist Central Hall was funded between 1898 and 1908 by the "Wesleyan Methodist Twentieth Century Fund" (or the "Million Guinea Fund", as it became more commonly known), whose aim was to raise one million guineas from one million Methodists. The fund closed in 1904 having raised 1,024,501 guineas (£1,075,727).[4] Central Hall Westminster was to act not only as a church, but to be of "great service for conferences on religious, educational, scientific, philanthropic and social questions".

Some of the early meetings of what became known as the suffragette movement took place at Methodist Central Hall in 1914, scenes were re-enacted in the 2015 film Suffragette, some of which was shot in the hall.[5]

Methodist Central Hall hosted the first meeting of the United Nations General Assembly in 1946.[1][3][6] In return for the use of the hall, the Assembly voted to fund the repainting of the walls of the church in a light blue. At the time it was being used by the UN General Assembly, the congregation relocated to the Coliseum Theatre.[1]

It has been regularly used for political rallies—famous speakers have included Mohandas Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Winston Churchill.[4] In September 1972 the Conservative Monday Club held a much publicised and packed "Halt Immigration Now!" public meeting in the main hall, addressed by several prominent speakers including members of parliament Ronald Bell, John Biggs-Davison, Harold Soref, and John Stokes.[7][8] and continued their use of the building until 1991 when they held two Seminars there.[9]

In 1968, Central Hall hosted the first public performance of Andrew Lloyd Webber's Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat[4] in a concert that also included his father (organist William Lloyd Webber who was Musical Director at Methodist Central Hall), his brother (cellist Julian Lloyd Webber) and pianist John Lill.[10]

The FIFA World Cup trophy was on display at Central Hall in early 1966 in preparation for the football tournament being held in England that summer. It was stolen from the hall on 20 March 1966 and was recovered seven days later in South London, but the thief was never caught. England went on to win the trophy four months later.[11]

In 2005 Central Hall controversially applied for a licence to sell alcohol in its café and conference venues. As the Methodist Church has traditionally promoted abstinence and usually forbids consumption of alcohol on church premises, many Methodists argued that the application was in defiance of church rules and a written objection was compiled.[12]

It is frequently used for public enquiries, including those into the Ladbroke Grove rail crash, the sinking of the Marchioness pleasure boat, and the Bloody Sunday incident in Northern Ireland.[4]

Today Methodist Central Hall is home to a thriving Christian church in the Methodist tradition, Central London's Largest Conference venue, (Central Hall Westminster Ltd) and the St Vincent's Family Project.

Architecture

Methodist Central Hall, Westminster was designed by Edwin Alfred Rickards, of the firm Lanchester, Stewart and Rickards.[3] This company also designed the City Hall building in Cathays Park, Cardiff, with which it shares many similarities. Although clad in an elaborate baroque style, to contrast with Westminster Abbey, it is an early example of the use of a reinforced concrete frame for a building in Britain.[14] The interior was similarly planned on a Piranesian scale, although the execution was rather more economical.

The original 1904 design included two small towers on the main (east) façade, facing Westminster Abbey. These were never built, supposedly because of an outcry that they would reduce the dominance of Nicholas Hawksmoor's west towers at Westminster Abbey in views from St. James's Park. The hall was eventually finished in 1911.

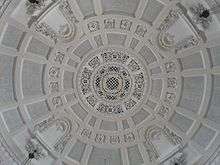

The domed ceiling of the Great Hall is reputed to be the second largest of its type in the world.[15] The vast scale of the self-supporting ferro-concrete structure reflects the original intention that Central Hall was intended to be "an open-air meeting place with a roof on".

The angels in the exterior spandrels were designed by Henry Poole.

Organ

The Organ was built in 1912 by William Hill & Sons and rebuilt and revised in 1970 by Rushworth and Dreaper. In 2011, Harrison & Harrison revised the layout, provided new slider soundboards and actions and painted the front pipes. The organ has 57 stops/68 ranks and 4,731 speaking pipes on four manuals and pedal. The stoplist since 2011:[16]

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Couplers: III-I, IV-I, I-II, III-II, IV-II, IV-III, Sub and Super III, Sub and Super III, Unison off III, Unison off IV, I-P, II-P, III-P, IV-P.

- 8 General Combinations, 8 Divisional Combinations for each Manual and the Pedal (on 256 Memory Levels); Continental Stepper (General Piston Sequencer + and -).

References

- 1 2 3 Janello, Amy; Jones, Brennon (1996). A Global Affair: An Inside Look at the United Nations. I.B.Tauris. p. 20. ISBN 1860641393. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ↑ "Organiser". Central Hall Westminster. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- 1 2 3 Wittich, John (1988). Churches, Cathedrals and Chapels. Gracewing Publishing. p. 102. ISBN 085244141X. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 "Background to the building". Central Hall Westminster. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ↑ "#Votes100 - Suffragette Movement and Methodist Central Hall - Methodist Central Hall, Westminster". Methodist Central Hall, Westminster. 2018-02-05. Retrieved 2018-02-12.

- ↑ "United Nations Day 2016 - #UN71 - Methodist Central Hall, Westminster". Methodist Central Hall, Westminster. 2016-10-24. Retrieved 2018-02-12.

- ↑ Monday News, Oct.1972 (Monday Club publication).

- ↑ Sunday Times, 14 January 1973

- ↑ Monday Club News, January 1992.

- ↑ "Methodist Central Hall Westminster, Songs of Praise - BBC One". BBC. Retrieved 2018-02-12.

- ↑ "1966: Football's World Cup stolen". BBC. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ↑ Eunice K. Y. Or (23 May 2005). "Methodist HQ Alcohol License Application Sparks Abstinence Debate". Christianity Today. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ↑ Group Travel – Methodist Church Conference Cente Central Hall Westminster London UK

- ↑ Rob Humphreys (2010). The Rough Guide to London. Rough Guides UK. ISBN 1405384778. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ↑ "Historic Weddings Venue Central Hall Westminster London UK". Central Hall Westminster London UK. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ↑ Great Organ at Westminster Central Hall . www.harrisonorgans.com. Retrieved May 9, 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Methodist Central Hall, London. |

- Methodist Central Hall – Church website

- Central Hall Westminster – Conference centre website

- The Sanctuary Westminster