Aravalli Range

| Aravalli Range | |

|---|---|

The Aravali Range in Rajasthan | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Guru Shikhar, Mount Abu |

| Elevation | 1,722 m (5,650 ft) |

| Coordinates | 24°35′33″N 74°42′30″E / 24.59250°N 74.70833°E |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 692 km (430 mi) |

| Naming | |

| Pronunciation | Hindustani pronunciation: [ aa ra vli] |

| Geography | |

Topographic map of India showing the range

| |

| Country |

|

| States | Rajasthan, Haryana, Delhi and Gujarat |

| Region | North India, Western India |

| Settlement | Delhi, Gurgaon, Mount Abu |

| Range coordinates | 25°00′N 73°30′E / 25°N 73.5°ECoordinates: 25°00′N 73°30′E / 25°N 73.5°E |

| Rivers | Banas, Luni, Sakhi and Sabarmati |

| Geology | |

| Orogeny | Aravalli-Delhi Orogen |

| Age of rock | Precambrian |

| Type of rock | Fold mountains from Plate tectonics |

The Aravalli Range is a range of mountains running approximately 692 km (430 mi) in a southwest direction, starting in North India from Delhi and passing through southern Haryana,[1] through to Western India across the states of Rajasthan and ending in Gujarat.[2][3]

Etymology

Aravalli, a composite Sanskrit word from "ara" and "vali", literally means the "line of peaks".[4][5]

Natural History

Geology

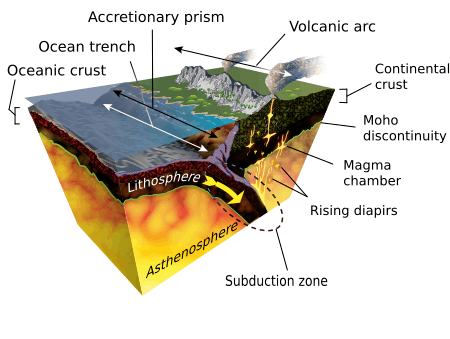

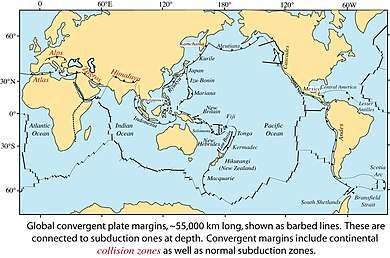

The Aravalli Range, an eroded stub of ancient mountains, is the oldest range of fold mountains in India.[6] The natural history of the Aravalli Range dates back to times when the Indian Plate was separated from the Eurasian Plate by an ocean. The Proterozoic Aravalli-Delhi orogenic belt in north west India is similar to the younger Himalayan-type orogenic belts of the Mesozoic-Cenozoic era (of the Phanerozoic) in terms of component parts and appears to have passed through a near-orderly Wilson supercontinental cycle of events. The range rose in a Precambrian event called the Aravalli-Delhi Orogen. The Aravalli Range is a northeast-southwest trending orogenic belt that is located in the northwestern part of Indian Peninsula. It is part of the Indian Shield that was formed from a series of cratonic collisions.[7] In ancient times, Aravalli were extremely high but since have worn down almost completely by millions of years of weathering, where as the Himalayas being young fold mountains are still continuously rising. Aravalli, being the old fold mountains, have stopped growing higher due to the cessation of upward thrust caused by the stopping of movement of the tectonic plates in the Earth's crust below them. The Aravalli Range joins two of the ancient earth's crust segments that make up the greater Indian craton, the Aravalli Craton which is the Marwar segment of earth's crust to the northwest of the Aravalli Range, and the Bundelkand Craton segment of earth's crust to the southeast of the Aravalli Range. Cratons, generally found in the interiors of tectonic plates, are old and stable parts of the continental lithosphere that has remained relatively undeformed during the cycles of merging and rifting of continents.

It consists of two main sequences formed in Proterozoic eon, metasedimentary rock (sedimentary rocks metamorphised under pressure and heat without melting) and metavolcanic rock (metamorphised volcanic rocks) sequences of the Aravalli Supergroup and Delhi Supergroup. These two supergroups rest over the Archean Bhilwara Gneissic Complex basement, which is a gneissic (high-grade metamorphism of sedimentary or igneous rocks) basement formed during the archean eon 4 Ga ago. It started as an inverted basin, that rifted and pulled apart into granitoid basement, initially during Aravalli passive rifting around 2.5 to 2.0 Ga years ago and then during Delhi active rifting around 1.9 to 1.6 Ga years ago. It started with rifting of a rigid Archaean continent banded gneissic complex around 2.2 Ga with the coexisting formation of the Bhilwara aulacogen in its eastern part and eventual rupturing and separation of the continent along a line parallel to the Rakhabdev (Rishabhdev) lineament to the west, simultaneous development of a passive continental margin with the undersea shelf rise sediments of the Aravalli-Jharol belts depositing on the attenuated crust on the eastern flank of the separated continent, subsequent destruction of the continental margin by accretion of the Delhi island arc (a type of archipelago composed of an arc-shaped chain of volcanoes closely situated parallel to a convergent boundary between two converging tectonic plates) from the west around 1.5 Ga. This tectonic plates collision event involved early thrusting with partial obduction (overthrusting of oceanic lithosphere onto continental lithosphere at a convergent plate boundary) of the oceanic crust along the Rakhabdev lineament, flattening and eventual wrenching (also called strike-slip plate fault, side ways horizontal movement of colliding plates with no vertical motion) parallel to the collision zone. Associated mafic igneous rocks show both continental and oceanic tholeiitic geochemistry (magnesium and iron rich igneous rocks) from phanerozoic eon (541–0 million) with rift-related magmatic rock formations.[8]

The Aravalli-Delhi Orogen is an orogen event that led to a large structural deformation of the Earth's lithosphere (crust and uppermost mantle, such as Aravalli and Himalayas fold mountains) due to the interaction between tectonic plates when a continental plate is crumpled and is pushed upwards to form mountain ranges, and involve a great range of geological processes collectively called orogenesis.[9][10]

Minerals

The archean basement had served as a rigid indentor which controlled the overall wedge shaped geometry of the orogen. Lithology of area shows that the base rocks of Aravalli are of Mewar Gneiss formed by high-grade regional metamorphic processes from preexisting formations that were originally sedimentary rock with earliest life form that were formed during the archean eon, these contain fossils of unicellular organism such as green algae and cyanobacteria in stromatolitic carbonate ocean reefs formed during the paleoproterozoic era. Sedimentary exhalative deposits of base metal sulfide ores formed extensively along several, long, linear zones in the Bhilwara aulacogen or produced local concentration in the rifted Aravalli continental margin, where rich stromatolitic phosphorites also formed. Tectonic evolution of the Aravalli Mountains shows Mewar Geniss rocks are overlain by Delhi Supergroup type of rocks that also have post-Aravalli intrusions. Metal sulfide ores were formed in two different epocs, lead and zinc sulfide ores were formed in the sedimentary rocks around 1.8 Ga years ago during Paleoproterozoic phase. The tectonic setting of Zinc-lead-copper sulfides mineralization in Delhi supergroup rocks in Haryana-Delhi were formed in mantle plume volcanic action around 1 Ga years ago covering Haryana and Rajasthan during mesoproterozoic. In the southern part of Aravalli supergroup arc base metal sulfides were generated near the subduction zone on the western fringe and in zones of back-arc extension to the south-east. Continued subduction produced W-Sn (Tungsten-Tin) mineralisation in S-type (sedimentary unmetamorphosed rock) felsic (volcanic rock) plutons (underground crystallised solidified magma). This includes commercially viable quantities of minerals, such as rock phosphate, lead-zinc-silver mineral deposits at Zawar, Rikahbdev serpentinite, talc and pyrophyllite) and asbestos, apatite, kyanite and beryl.[11][12]

Mining

Mining of copper and other metals in the Aravalli range dates back to at least the 5th century BCE, based on carbon dating.[13][14] Recent research indicates that copper was already mined here during the Sothi-Siswal period going back to c. 4000 BCE. Ancient Kalibangan and Kunal, Haryana settlements obtained copper here.[15]

Geographical features

The Aravalli Range can be divided into the following parts (north to south direction):

- Archean basement, is a Banded Gneissic Complex (BGC) with schists (medium grade metamorphic rock), gneisses (high grade regional metamorphic rock), composite gneiss and quartzites. It forms the basement rock for both Delhi Supergroup and Aravalli Supergroup.

- Delhi Supergroup

- Alwar Group, with arenaceous and mafic volcanic rocks

- Delhi Ridge, in north

- Haryana Aravalli ranges, in the west

- Tosham Hill range, basement rocks are quartzite with chiastolite, the upper layers of quartz porphyry ring dyke, felsite, welded tuff and muscovite biotite granite rocks have commercially nonviable tin, tungsten and copper.

- Rajasthan Alwar range, in the east

- Ajabgarh Group-Kumbhalgarh Group, with Carbonate, mafic volcanic and argillaceous rocks

- Raialo Group, with Mafic volcanic and calcareous rocks

- Alwar Group, with arenaceous and mafic volcanic rocks

- Aravalli Supergroup

- Debari Group, with Carbonates, quartzite, and pelitic rocks

- Jharol Group, with Turbidite facies and argillaceous rocks

The Tosham Hill Range, west of Bhiwani, Haryana is the northernmost end of the Aravalli range. A north eastern extension of Aravalli extends in the national capital of India too, locally known as ridge it diagonally traverses to the South Delhi (hills of Asola Bhatti Wildlife Sanctuary), where at the hills of Bandhwari, it meets the Haryana Aravalli range consisting of various isolated hills and rocky ridges passing along the southern border of Haryana.[16]

The Aravalli supergroup passes through Rajasthan state, dividing it into two halves, with three-fifths of Rajasthan on the western side towards Thar Desert and two third on the eastern side consisting of the catchment area of Banas and Chambal rivers bordering the state of Madhya Pradesh. Guru Shikhar, the highest peak in the Aravalli Range at 5650 feet (1722 meters) in Mount Abu of Rajasthan, lies near the south-western extremity of the Central Aravalli range, close to the border with Gujarat state. The southern Aravalli Supergroup enters the northeast of Gujarat near Modasa where it lends its name to the Aravalli district, and ends at the center of the state at Palanpur near Ahmedabad.

Human history

The Aravalli Range has been site of three broad stages of human history, early stone age saw the use of flint stones; mid-stone age starting from 20,000 BP saw the domestication of cattle for agriculture; and post stone age starting from 10,000 BP saw the development of the Kalibangan civilization, 4,000 years old Aahar civilization and 2,800 years old Gneshwar civilization, Aarayan civilization and Vedic era civilizations.

Post stone age

Ganeshwar sunari Cultural Complex

Ganeshwar sunari Cultural Complex (GSCC) is a collection of third millennium BC settlements in the area of the Aravalli Hill Range. Among them, there are similarities in material culture, and in the production of copper tools. They are located near the copper mines.

"The GSCC is east of the Harappan culture, to the north-east of Ahar-Banas Complex, north/north west to the Kayatha Culture and at a later date, west of the OCP-Copper Hoard sites (Ochre Coloured Pottery culture-Copper Hoard Culture). Located within the regions of the Aravalli Hill Range, primarily along the Kantli, Sabi, Sota, Dohan and Bondi rivers, the GJCC is the largest copper producing community in third millennium BC South Asia, with 385 sites documented. Archaeological indicators of the GSCC were documented primarily in Jaipur, Jhunjhunu, and Sikar districts of Rajasthan, India ..."[17]

Among their pottery, we find the incised ware, and reserved slip ware.

There are two main type sites, Ganeshwar, and Sunari, in Tehsil Kot Putli, Jaipur District (Geo coordinates: N 27° 35' 51", 76° 06' 85" E).

Environment

Climate

The Northern Aravalli range in Delhi and Haryana has humid subtropical climate and hot semi-arid climate continental climate with very hot summers and relatively cool winters.[18] The main characteristics of climate in Hisar are dryness, extremes of temperature, and scanty rainfall.[19] The maximum daytime temperature during the summer varies between 40 and 46 °C (104 and 115 °F). During winter, its ranges between 1.5 and 4 °C.[20]

The Central Aravalli range in Rajasthan has an arid and dry climate.

The Southern Aravalli range in Gujarat has a tropical wet and dry climate

Rivers

Following rivers flow from the Aravalli range.

- North-to-south flowing rivers, originate from the western slopes of Aravalli range in Rajasthan, pass through the southeastern portion of the Thar Desert, and end into Gujarat.

- Luni River, originates in the Pushkar valley near Ajmer, ends in the marshy lands of Rann of Kutch.

- Sakhi river, ends in the marshy lands of Rann of Kutch.

- Sabarmati River, originates one the western slopes of Aravalli range of the Udaipur District, end into the Gulf of Cambay of Arabian Sea.

- West to north-west flowing rivers, originate from the western slopes of Aravalli range in Rajasthan, flow through semi-arid historical Shekhawati region, drain into southern Haryana. Several Ochre Coloured Pottery culture sites, also identified as late Harappan phase of Indus Valley Civilisation culture,[21] has been found along the banks of these rivers.

- Sahibi River, originates near Manoharpur in Sikar district flows through Haryana, along with its following tributaries:[22][23][24][25]

- Dohan river, tributary of Sahibi river, originates near Neem Ka Thana in Sikar district).

- Sota River, tributary of Sahibi river, merges with Sahibi river at Behror in Alwar district.

- Krishnavati river, former tributary of Sahibi river, originates near Dariba copper mines in Rajsamand district of Rajasthan, flows through Patan in Dausa district and Mothooka in Alwar district, then disappears in Mahendragarh district in Haryana much before reaching Sahibi river.

- Sahibi River, originates near Manoharpur in Sikar district flows through Haryana, along with its following tributaries:[22][23][24][25]

- West to north-east flowing rivers, originating from the eastern slopes of Aravalli range in Rajasthan, flow northwards to Yamuna.

- Chambal River, a southern-side tributary of Yamuna river.

- Banas River, a northern-side tributary of Chambal river.

- Berach River, a southern-side tributary of Banas River, originates in the hills of Udaipur District.

- Ahar River, a right-side (or eastern side) tributary of the Berach river, originates in the hills of Udaipur District, flows through Udaipur city forming the famous Lake Pichola.

- Wagli River, a right-side tributary of the Berach River.

- Wagon River, a right-side tributary of the Berach River.

- Gambhiri River, a right-side tributary of the Berach river.

- Orai River, a right-side tributary of the Berach River.

- Berach River, a southern-side tributary of Banas River, originates in the hills of Udaipur District.

- Banas River, a northern-side tributary of Chambal river.

- Chambal River, a southern-side tributary of Yamuna river.

Ecology

Flora

The Aravalli Range has several forests with a diversity of environment.[26]

Fauna

The Aravalli Range is rich in wildlife. The first ever 2017 wildlife survey of 200 square meter area cross five districts (Gurgaon, Faridabad, Mewat, Rewari and Mahendergarh) of Haryana done by the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) found 14 species, including leopards, striped hyena (7 sightings), golden jackal (9 sightings, with 92% occupancy across the survey area), nilgai (55 sightings), palm civet (7 sightings), wild pig (14 sightings), rhesus macaque (55 sightings), peafowl (57 sightings) and Indian crested porcupine (12 sightings). Encouraged by first survey, wildlife department has prepared a plan for the comprehensive study and census of wildlife across the whole Aravalli range, including radio collar tracking of the wild animals.[26]

Concerns

In May 1992, some parts of the Aravalli hills in Rajasthan and Haryana were protected from mining through the Ecologically Sensitive Areas clauses of Indian laws. In 2003, the central government of India prohibited mining operations in these areas. In 2004, India's Supreme Court banned mining in the notified areas of Aravalli Range. In May 2009, the Supreme Court extended the ban on mining in an area of 448 km2 across the Faridabad, Gurgaon and Mewat districts in Haryana, covering the Aravalli Range.[27][28]

A 2013 report used high resolution Cartosat-1 & LISS-IV satellite imaging to determine the existence and condition of mines in the Aravalli Range. In the Guru Gram district, the Aravalli hills occupy an area of 11,256 hectares, of which 491 (4.36%) hectares had mines, of which 16 hectares (0.14%) were abandoned flooded mines. In the Faridabad and Mewat districts, about 3610 hectares were part of mining industry, out of a total of 49,300 hectares. These mines were primarily granite and marble quarries for India's residential and real estate construction applications.[29] In the Central Rajasthan region, Sharma states that the presence of some mining has had both positive and negative effects on neighboring agriculture and the ecosystem. The rain induced erosion brings nutrients as well as potential contaminants.[30]

Economy

The Aravali Range is the source area of many rivers, resulting in development of human settlements with sustainable economy since pre-historic times. The Delhi Mumbai Industrial Corridor Project, Western Dedicated Freight Corridor, Mumbai–Ahmedabad high-speed rail corridor, North Western Railway network, Jaipur-Kishangarh Expressway and Delhi-Jaipur Expressway, all run parallel to the length of the Aravalli Range providing an economic boost.[31]

Tourism

Aravali range is the home of several forests, wildlife and protected areas, UNESCO heritage listed forts, hundreds of rivers and ancient history to sustain a large tourism industry.

Concerns

Damage to the environment and ecology from the unorganised urbanisation, overexploitation of the natural resources including water and minerals, mining, untreated human waste and disposal, pollution, loss of forest cover and wildlife habitat, unprotected status of most of the Aravalli and the lack of an integrated Aravalli management agency are the major causes of concern.

Gallery

The Aravali Range inside Ranthambhore National Park, in Rajasthan.

The Aravali Range inside Ranthambhore National Park, in Rajasthan. Aravalli range near Udaipur Rajasthan

Aravalli range near Udaipur Rajasthan

See also

Further reading

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aravalli Range. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Western India. |

- Aravali Range Homepage India Environment Portal

- Rainfall

Books

- Watershed Management in Aravali Foothills, by Gurmel Singh, S. S. Grewal, R. C. Kaushal. Published by Central Soil & Water Conservation Research & Training Institute, 1990.

References

- ↑ "Aravalli Biodiversity Park, Gurgaon". Archived from the original on 2012-05-28.

- ↑ Kohli, M.S. (2004), Mountains of India: Tourism, Adventure, Pilgrimage, Indus Publishing, pp. 29–, ISBN 978-81-7387-135-1

- ↑ Dale Hoiberg; Indu Ramchandani (2000). "Aravali Range". Students' Britannica India. Popular Prakashan. pp. 92–93. ISBN 0-85229-760-2.

- ↑ George Smith (1882). The Geography of British India, Political & Physical. J. Murray. p. 23.

- ↑ "Aravali Range". Britannica.com.

- ↑ Roy, A. B. (1990). Evolution of the Precambrian crust of the Aravalli Range. Developments in Precambrian Geology, 8, 327-347.

- ↑ Mishra, D.C.; Kumar, M. Ravi. Proterozoic orogenic belts and rifting of Indian cratons: Geophysical constraints. Geoscience Frontiers. 2013 March. 5: 25–41.

- ↑ P. K. VermaR. O. Greiling, December 1995, "Tectonic evolution of the Aravalli orogen (NW India): an inverted Proterozoic rift basin?", Geologische Rundschau, Volume 84, Issue 4, pp 683–696.

- ↑ Tony Waltham (2009). Foundations of Engineering Geology (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 20. ISBN 0-415-46959-7.

- ↑ Philip Kearey; Keith A. Klepeis; Frederick J. Vine (2009). "Chapter 10: Orogenic belts". Global Tectonics (3rd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. p. 287. ISBN 1-4051-0777-4.

- ↑ M. Deb and Wayne David Goodfellow, 2004, "Sediment Hosted Lead-Zinc Sulphide Deposits", Narosa Publishing, pp 260.

- ↑ Naveed Qamar, "Indian shield rocks".

- ↑ SM Gandhi (2000) Chapter 2 – Ancient Mining and Metallurgy in Rajasthan, Crustal Evolution and Metallogeny in the Northwestern Indian Shield: A Festschrift for Asoke Mookherjee, ISBN 978-1842650011

- ↑ Shrivastva, R. (1999). Mining of copper in ancient India. Indian Journal of History of Science, 34, 173-180

- ↑ Jane McIntosh, The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. Understanding ancient civilizations. ABC-CLIO, 2008 ISBN 1576079074 p77

- ↑ Bhuiyan, C., Singh, R. P., & Kogan, F. N. (2006). Monitoring drought dynamics in the Aravalli region (India) using different indices based on ground and remote sensing data. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, 8(4), 289-302

- ↑ Uzma Z. Rizvi (2010) Indices of Interaction: Comparisons between the Ahar-Banas and Ganeshwar Jodhpura Cultural Complex Archived May 9, 2016, at the Wayback Machine., in EASAA 2007: Special Session on Gilund Excavations, edited by T. Raczek and V. Shinde, pp. 51-61. British Archaeological Reports: ArchaeoPress

- ↑ "Climate of Hisar". PPU. Archived from the original on 5 May 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ↑ "Climate of Hisar". District Administration, Hisar. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ↑ "More snowfall in Himachal". The Hindu. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ↑ Gupta, S.P. (ed.) (1995), The lost Sarasvati and the Indus Civilization, Jodhpur: Kusumanjali Prakashan

- ↑ Cultural Contours of India: Dr. Satya Prakash Felicitation Volume, Vijai Shankar Śrivastava, 1981. ISBN 0391023586

- ↑ Sahibi river

- ↑ Google Books: Page 41, 42, 43, 44, 47 (b) Sahibi Nadi (River), River Pollution, By A.k.jain

- ↑ Minerals and Metals in Ancient India: Archaeological evidence, Arun Kumar Biswas, Sulekha Biswas, University of Michigan. 1996. ISBN 812460049X.

- 1 2 Aravalis in Gurugram, Faridabad core area for leopards, finds survey, The Times of India, 17 June 2017

- ↑ SC bans all mining activity in Aravali hills area of Haryana, 9 May 2009.

- ↑ Mission Green: SC bans mining in Aravali hills Hindustan Times, 9 May 2009.

- ↑ Rai and Kumar, MAPPING OF MINING AREAS IN ARAVALLI HILLS IN GURGAON, FARIDABAD & MEWAT DISTRICTS OF HARYANA USING GEO-INFORMATICS TECHNOLOGY, International Journal of Remote Sensing & Geoscience, Volume 2, Issue 1, Jan. 2013

- ↑ Sharma, K. C. (2003). Perplexities and Ecoremediation of Central Aravallis of Rajasthan. Environmental Scenario for 21st Century, ISBN 978-8176484183, Chapter 20

- ↑ Jha, Bagis, TNN. 195-km super expressway to link Delhi, Jaipur, The Economic Times, 21 March 2017, Accessed on 20 June 2017.