Precambrian

| Precambrian Eon 4600–541 million years ago | |

view • discuss • -4500 — – -4000 — – -3500 — – -3000 — – -2500 — – -2000 — – -1500 — – -1000 — – -500 — – 0 — |

The Precambrian (or Pre-Cambrian, sometimes abbreviated pЄ, or Cryptozoic) is the earliest part of Earth's history, set before the current Phanerozoic Eon. The Precambrian is so named because it preceded the Cambrian, the first period of the Phanerozoic eon, which is named after Cambria, the Latinised name for Wales, where rocks from this age were first studied. The Precambrian accounts for 88% of the Earth's geologic time.

The Precambrian (colored green in the timeline figure) is an informal unit of geologic time,[1] subdivided into three eons (Hadean, Archean, Proterozoic) of the geologic time scale. It spans from the formation of Earth about 4.6 billion years ago (Ga) to the beginning of the Cambrian Period, about 541 million years ago (Ma), when hard-shelled creatures first appeared in abundance.

Overview

Relatively little is known about the Precambrian, despite it making up roughly seven-eighths of the Earth's history, and what is known has largely been discovered from the 1960s onwards. The Precambrian fossil record is poorer than that of the succeeding Phanerozoic, and fossils from the Precambrian (e.g. stromatolites) are of limited biostratigraphic use.[2] This is because many Precambrian rocks have been heavily metamorphosed, obscuring their origins, while others have been destroyed by erosion, or remain deeply buried beneath Phanerozoic strata.[2][3][4]

It is thought that the Earth coalesced from material in orbit around the Sun at roughly 4,543 Ma, and may have been struck by a very large (Mars-sized) planetesimal shortly after it formed, splitting off material that formed the Moon (see Giant impact hypothesis). A stable crust was apparently in place by 4,433 Ma, since zircon crystals from Western Australia have been dated at 4,404 ± 8 Ma.[5]

The term "Precambrian" is recognized by the International Commission on Stratigraphy as the only "supereon" in geologic time; it is so called because it includes the Hadean (~4.6—4 billion), Archean (4—2.5 billion), and Proterozoic (2.5 billion—541 million) eons. (There is only one other eon: the Phanerozoic, 541 million-present.)[6] "Precambrian" is still used by geologists and paleontologists for general discussions not requiring the more specific eon names. As of 2010, the United States Geological Survey considers the term informal, lacking a stratigraphic rank.[7]

Life forms

A specific date for the origin of life has not been determined. Carbon found in 3.8 billion-year-old rocks (Archean eon) from islands off western Greenland may be of organic origin. Well-preserved microscopic fossils of bacteria older than 3.46 billion years have been found in Western Australia.[8] Probable fossils 100 million years older have been found in the same area. However, there is evidence that life could have evolved over 4.280 billion years ago.[9][10][11][12] There is a fairly solid record of bacterial life throughout the remainder (Proterozoic eon) of the Precambrian.

Excluding a few contested reports of much older forms from North America and India, the first complex multicellular life forms seem to have appeared at roughly 1500 Ma, in the Mesoproterozoic era of the Proterozoic eon. Fossil evidence from the later Ediacaran period of such complex life comes from the Lantian formation, at least 580 million years ago. A very diverse collection of soft-bodied forms is found in a variety of locations worldwide and date to between 635 and 542 Ma. These are referred to as Ediacaran or Vendian biota. Hard-shelled creatures appeared toward the end of that time span, marking the beginning of the Phanerozoic eon. By the middle of the following Cambrian period, a very diverse fauna is recorded in the Burgess Shale, including some which may represent stem groups of modern taxa. The increase in diversity of lifeforms during the early Cambrian is called the Cambrian explosion of life.[13][14]

While land seems to have been devoid of plants and animals, cyanobacteria and other microbes formed prokaryotic mats that covered terrestrial areas.[15]

Tracks from an animal with leg like appendages have been found in what was mud 551 million years ago.[16]

Planetary environment and the oxygen catastrophe

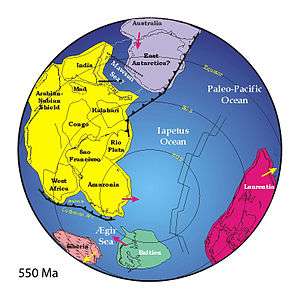

Evidence of the details of plate motions and other tectonic activity in the Precambrian has been poorly preserved. It is generally believed that small proto-continents existed prior to 4280 Ma, and that most of the Earth's landmasses collected into a single supercontinent around 1130 Ma. The supercontinent, known as Rodinia, broke up around 750 Ma. A number of glacial periods have been identified going as far back as the Huronian epoch, roughly 2400–2100 Ma. One of the best studied is the Sturtian-Varangian glaciation, around 850–635 Ma, which may have brought glacial conditions all the way to the equator, resulting in a "Snowball Earth".

The atmosphere of the early Earth is not well understood. Most geologists believe it was composed primarily of nitrogen, carbon dioxide, and other relatively inert gases, and was lacking in free oxygen. There is, however, evidence that an oxygen-rich atmosphere existed since the early Archean.[17]

At present, it is still believed that molecular oxygen was not a significant fraction of Earth's atmosphere until after photosynthetic life forms evolved and began to produce it in large quantities as a byproduct of their metabolism. This radical shift from a chemically inert to an oxidizing atmosphere caused an ecological crisis, sometimes called the oxygen catastrophe. At first, oxygen would have quickly combined with other elements in Earth's crust, primarily iron, removing it from the atmosphere. After the supply of oxidizable surfaces ran out, oxygen would have begun to accumulate in the atmosphere, and the modern high-oxygen atmosphere would have developed. Evidence for this lies in older rocks that contain massive banded iron formations that were laid down as iron oxides.

Subdivisions

A terminology has evolved covering the early years of the Earth's existence, as radiometric dating has allowed real dates to be assigned to specific formations and features.[18] The Precambrian is divided into three eons: the Hadean (4600–4000 Ma), Archean (4000-2500 Ma) and Proterozoic (2500-541 Ma). See Timetable of the Precambrian.

- Proterozoic: this eon refers to the time from the lower Cambrian boundary, 541 Ma, back through 2500 Ma. As originally used, it was a synonym for "Precambrian" and hence included everything prior to the Cambrian boundary. The Proterozoic eon is divided into three eras: the Neoproterozoic, Mesoproterozoic and Paleoproterozoic.

- Neoproterozoic: The youngest geologic era of the Proterozoic Eon, from the Cambrian Period lower boundary (541 Ma) back to 1000 Ma. The Neoproterozoic corresponds to Precambrian Z rocks of older North American geology.

- Ediacaran: The youngest geologic period within the Neoproterozoic Era. The "2012 Geologic Time Scale" dates it from 541 to 635 Ma. In this period the Ediacaran fauna appeared.

- Cryogenian: The middle period in the Neoproterozoic Era: 635-720 Ma.

- Tonian: the earliest period of the Neoproterozoic Era: 720-1000 Ma.

- Mesoproterozoic: the middle era of the Proterozoic Eon, 1000-1600 Ma. Corresponds to "Precambrian Y" rocks of older North American geology.

- Paleoproterozoic: oldest era of the Proterozoic Eon, 1600-2500 Ma. Corresponds to "Precambrian X" rocks of older North American geology.

- Neoproterozoic: The youngest geologic era of the Proterozoic Eon, from the Cambrian Period lower boundary (541 Ma) back to 1000 Ma. The Neoproterozoic corresponds to Precambrian Z rocks of older North American geology.

- Archean Eon: 2500-4000 Ma.

- Hadean Eon: 4000–4600 Ma. This term was intended originally to cover the time before any preserved rocks were deposited, although some zircon crystals from about 4400 Ma demonstrate the existence of crust in the Hadean Eon. Other records from Hadean time come from the moon and meteorites.[19]

It has been proposed that the Precambrian should be divided into eons and eras that reflect stages of planetary evolution, rather than the current scheme based upon numerical ages. Such a system could rely on events in the stratigraphic record and be demarcated by GSSPs. The Precambrian could be divided into five "natural" eons, characterized as follows:[20]

- Accretion and differentiation: a period of planetary formation until giant Moon-forming impact event.

- Hadean: dominated by heavy bombardment from about 4.51 Ga (possibly including a Cool Early Earth period) to the end of the Late Heavy Bombardment period.

- Archean: a period defined by the first crustal formations (the Isua greenstone belt) until the deposition of banded iron formations due to increasing atmospheric oxygen content.

- Transition: a period of continued iron banded formation until the first continental red beds.

- Proterozoic: a period of modern plate tectonics until the first animals.

Precambrian supercontinents

The movement of Earth's plates has caused the formation and break-up of continents over time, including occasional formation of a supercontinent containing most or all of the landmass. The earliest known supercontinent was Vaalbara. It formed from proto-continents and was a supercontinent 3.636 billion years ago. Vaalbara broke up c. 2.845–2.803 Ga ago. The supercontinent Kenorland was formed c. 2.72 Ga ago and then broke sometime after 2.45–2.1 Ga into the proto-continent cratons called Laurentia, Baltica, Yilgarn craton, and Kalahari. The supercontinent Columbia or Nuna formed 2.06–1.82 billion years ago and broke up about 1.5–1.35 billion years ago.[21][22] The supercontinent Rodinia is thought to have formed about 1.13–1.071 billion years ago, to have embodied most or all of Earth's continents and to have broken up into eight continents around 750–600 million years ago.

See also

References

- ↑ Gradstein, F.M.; Ogg, J.G.; Schmitz, M.D.; Ogg, G.M. (editors) (2012). The Geologic Timescale 2012 (volume 1). Elsevier. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-44-459390-0.

- 1 2 Monroe, James S.; Wicander, Reed (1997). The Changing Earth: Exploring Geology and Evolution (2nd ed.). Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing Company. p. 492. ISBN 9781285981383.

- ↑ Levin, Harold L. (25 October 2005). "The Earliest Earth: 2,100,000,000 years of the Archean Eon". In Gore, Pamela J.W. The Earth Through Time. p. 1.

- ↑ Davis, C.M. (1964). "The Precambrian Era". Readings in the Geography of Michigan. Michigan State University.

- ↑ "Zircons are Forever". Department of Geoscience. 2005. Retrieved 28 April 2007.

- ↑ Fan, Junxuan; Hou, Xudong (February 2017). "Chart". International Commission on Stratigraphy. International Chronostratigraphic Chart. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey Geologic Names Committee (2010), "Divisions of geologic time—major chronostratigraphic and geochronologic units", U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet 2010–3059, United States Geological Survey, p. 2, retrieved 20 June 2018

- ↑ Brun, Yves; Shimkets, Lawrence J. (January 2000). Prokaryotic development. ASM Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-55581-158-7.

- ↑ Dodd, Matthew S.; Papineau, Dominic; Grenne, Tor; slack, John F.; Rittner, Martin; Pirajno, Franco; O'Neil, Jonathan; Little, Crispin T. S. (2 March 2017). "Evidence for early life in Earth's oldest hydrothermal vent precipitates". Nature. 543 (7643): 60–64. Bibcode:2017Natur.543...60D. doi:10.1038/nature21377. PMID 28252057. Archived from the original on 10 February 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- ↑ Zimmer, Carl (1 March 2017). "Scientists Say Canadian Bacteria Fossils May Be Earth's Oldest". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- ↑ Ghosh, Pallab (1 March 2017). "Earliest evidence of life on Earth 'found'". BBC News. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- ↑ Dunham, Will (1 March 2017). "Canadian bacteria-like fossils called oldest evidence of life". Reuters. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ↑ Fedonkin, Mikhail A.; Gehling, James G.; Grey, Kathleen; Narbonne, Guy M.; Vickers-Rich, Patricia (2007). The Rise of Animals: Evolution and Diversification of the Kingdom Animalia. JHU Press. p. 326. doi:10.1086/598305. ISBN 9780801886799.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard; Wong, Yan (2005). The Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of Evolution. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 673. ISBN 9780618619160.

- ↑ Selden, Paul A. (2005). "Terrestrialization (Precambrian-Devonian)". Terrestrialization (Precambrian–Devonian) (PDF). Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1038/npg.els.0004145. ISBN 978-0470016176.

- ↑ Scientists discover 'oldest footprints on Earth' in southern China dating back 550 million years The Independent

- ↑ Clemmey, Harry; Badham, Nick (1982). "Oxygen in the Precambrian Atmosphere". Geology. 10 (3): 141–146. Bibcode:1982Geo....10..141C. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1982)10<141:OITPAA>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Geological Society of America's "2009 GSA Geologic Time Scale."

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-05-10. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- ↑ Bleeker, W. (2004) [2004]. "Toward a "natural" Precambrian time scale". In Felix M. Gradstein; James G. Ogg; Alan G. Smith. A Geologic Time Scale 2004. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78673-7. also available at Stratigraphy.org: Precambrian subcommission

- ↑ Zhao, Guochun; Cawood, Peter A.; Wilde, Simon A.; Sun, M. (2002). "Review of global 2.1–1.8 Ga orogens: implications for a pre-Rodinia super-continent". Earth-Science Reviews. 59 (1): 125–162. Bibcode:2002ESRv...59..125Z. doi:10.1016/S0012-8252(02)00073-9.

- ↑ Zhao, Guochun; Sun, M.; Wilde, Simon A.; Li, S.Z. (2004). "A Paleo-Mesoproterozoic super-continent: assembly, growth and breakup". Earth-Science Reviews (Submitted manuscript). 67 (1): 91–123. Bibcode:2004ESRv...67...91Z. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2004.02.003.

Further reading

- Valley, John W., William H. Peck, Elizabeth M. King (1999) Zircons Are Forever, The Outcrop for 1999, University of Wisconsin-Madison Wgeology.wisc.edu – Evidence from detrital zircons for the existence of continental crust and oceans on the Earth 4.4 Gyr ago Accessed Jan. 10, 2006

- Wilde, S. A.; Valley, J. W.; Peck, W. H.; Graham, C. M. (2001). "Evidence from detrital zircons for the existence of continental crust and oceans on the Earth 4.4 Gyr ago". Nature. 409 (6817): 175–178. doi:10.1038/35051550. PMID 11196637.

- Wyche, S.; Nelson, D. R.; Riganti, A. (2004). "4350–3130 Ma detrital zircons in the Southern Cross Granite–Greenstone Terrane, Western Australia: implications for the early evolution of the Yilgarn Craton". Australian Journal of Earth Sciences. 51 (1): 31–45. Bibcode:2004AuJES..51...31W. doi:10.1046/j.1400-0952.2003.01042.x.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Precambrian. |

External links

- Late Precambrian Supercontinent and Ice House World from the Paleomap Project