Sonoma, California

Sonoma is a city in Sonoma County, California in Sonoma Valley. Known as a part of Wine Country in the Sonoma Valley AVA Appellation, Sonoma is the home of the Sonoma International Film Festival and an historic town plaza, a remnant of the town's Mexican colonial past. Sonoma's population was 10,648 as of the 2010 census, while the Sonoma urban area had a population of 32,678.[11]

Sonoma, California | |

|---|---|

City | |

.jpg) _-_Sonoma_State_Historic_Park.jpg) _(cropped).jpg) _(cropped).jpg) | |

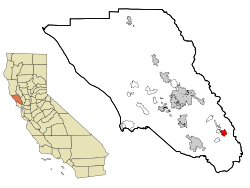

Location in Sonoma County and California | |

Sonoma, California Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 38°17′20″N 122°27′32″W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Sonoma |

| Incorporated | September 3, 1883[2] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager[3] |

| • Mayor | Amy Harrington[4] |

| • City Manager | Cathy Capriola[5] |

| Area | |

| • City | 2.74 sq mi (7.11 km2) |

| • Land | 2.74 sq mi (7.11 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) 0% |

| Elevation | 85 ft (26 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 10,648 |

| • Estimate (2019)[9] | 11,024 |

| • Density | 4,028.43/sq mi (1,555.62/km2) |

| • Metro | 483,878 |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| ZIP code | 95476 |

| Area code | 707 |

| FIPS code | 06-72646 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 277617, 2411929 |

| Website | www |

History

Origins

When the first Europeans arrived, the area was near the northeast corner of the Coast Miwok territory,[12] with Southern Pomo to the northwest, Wappo to the northeast, Suisunes and Patwin peoples to the east.[13][14]

Mission Period

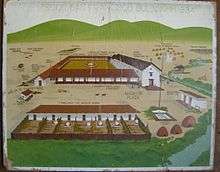

Mission San Francisco Solano was the predecessor of the Pueblo of Sonoma. The Mission, established in 1823 by Father José Altimira of the Franciscan Order was the 21st, last and northernmost mission built in Alta California. It was the only mission built in Alta California after Mexico gained independence from the Spanish Empire.[15] In 1833 the Mexican Congress decided to close all of the missions in Alta California. The Spanish missionaries were to be replaced by parish priests.[16] The commander of the Company of the National Presidio at San Francisco (Compania de Presidio Nacional de San Francisco), Lieutenant Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo was appointed administrator (comisionado) to oversee the closing of Mission San Francisco Solano.[17] Governor José Figueroa's naming of Lieutenant Vallejo as the administrator to secularize the Mission was part of a larger plan.

Military - Rancho Period

Governor Figueroa had received instructions from the National Government to establish a strong presence in the region north of the San Francisco Bay to protect the area from encroachments of foreigners.[18] An immediate concern was the further eastward movement of the Russian America Company from their settlements at Fort Ross and Bodega Bay on the California coast.[19]

Figueroa's next step in implementing his instructions was to name Lieutenant Vallejo as Military Commander of the Northern Frontier, and to order the soldiers, arms and materiel at the Presidio of San Francisco moved to the site of the recently secularized Mission San Francisco Solano. The Sonoma Barracks were built to house the soldiers. Until the building was habitable, the troops were housed in the buildings of the old Mission.[20] In 1834, George C. Yount, the first Euro-American permanent settler in the Napa Valley, was employed as a carpenter by General Vallejo.

The Governor granted Lieutenant Vallejo the initial lands (approximately 44,000 acres (178 km2)) of Rancho Petaluma immediately west of Sonoma. Vallejo was also named Director of Colonization which meant that he could initiate land grants for other colonists (subject to the approval of the governor) and the diputación (Alta California's legislature).[21]

Vallejo had also been instructed by Governor Figueroa to establish a pueblo at the site of the old Mission. In 1835, with the assistance of William A. Richardson, he laid out, in accordance with the Spanish Laws of the Indies, the streets, lots, central plaza and broad main avenue of the new Pueblo de Sonoma.[22]

Although Sonoma had been founded as a pueblo in 1835, it remained under military control, lacking the political structures of municipal self-government of other Alta California pueblos. In 1843, Lieutenant Colonel Vallejo wrote to the Governor recommending that a civil government be organized for Sonoma. A town council (ayuntamiento) was established in 1844 and Jacob P. Leese was named first alcalde, and Cayetano Juarez second alcalde.[23]

Bear Flag Revolt

Before dawn on Sunday, June 14, 1846, thirty-three Americans, already in rebellion against the Alta California government, arrived in Sonoma. Some of the group had traveled from the camp of U.S. Army Brevet Captain John C. Frémont who had entered California in late 1845 with his exploration and mapping expedition. Others had joined along the way. As the number of immigrants arriving in California had swelled, the Mexican government barred them from buying or renting land and threatened them with expulsion because they had entered without official permission.[24][25] Mexican officials were concerned about the coming war with the United States coupled with the growing influx of American immigrants into California.[26]

A group of rebellious Americans had departed from Frémont's camp on June 10 and captured a herd of 170 Mexican government-owned horses being moved by Californio soldiers from San Rafael and Sonoma to Alta California's Commandante General José Castro in Santa Clara.[27] The insurgents next determined to seize the weapons and materiel stored in the Sonoma Barracks and to deny Sonoma to the Californios as a rallying point north of San Francisco Bay.[28]

Meeting no resistance, they approached Comandante Vallejo's home and pounded on his door. After a few minutes Vallejo opened the door dressed in his Mexican Army uniform.[29] Vallejo invited the filibusters' leaders into his home to negotiate terms. However, when the agreement was presented to those outside they refused to endorse it. Rather than releasing the Mexican officers under parole they insisted they be held as hostages. William Ide gave an impassioned speech urging the rebels to stay in Sonoma and start a new republic.[30] Referring to the stolen horses Ide ended his oration with "Choose ye this day what you will be! We are robbers, or we must be conquerors!"[31] At that time, Vallejo and his three associates were placed on horseback and taken to Frémont accompanied by eight or nine of the insurgents who did not favor forming a new republic under the circumstances.[32]

The Sonoma Barracks became the headquarters for the remaining twenty-four rebels, who within a few days created their Bear Flag. After the flag was raised Californios called the insurgents Los Osos (The Bears) because of their flag and in derision of their often scruffy appearance. The rebels embraced the expression, and their uprising became known as the Bear Flag Revolt.[33]

There were some small unit skirmishes between the Bears and the Californios but no major confrontations. Hearing reports that Mexican General José Castro was preparing to attack, Frémont left his camp near Sutter's Fort for Sonoma on June 23. With him were ninety men - his own party plus some trappers and settlers.[34][35]

On July 5, Frémont called a public meeting and proposed to the Bears that they unite with his party and form a single military unit. He said that he would accept command if they would pledge obedience, proceed honorably, and not violate the chastity of women. A compact was drawn up which all volunteers of the California Battalion signed or made their marks.[36] The next day Frémont, leaving the fifty men of Company B at the Barracks to defend Sonoma, left with the rest of the Battalion for Sutter's Fort. They took with them two of the captured Mexican field pieces, as well as muskets, a supply of ammunition, blankets, horses, and cattle.[37]

War against Mexico had already been declared by the United States Congress on May 13, 1846.[38] Because of the slow cross-continent communication of the time, no one in California knew that conclusively. Commodore John D. Sloat, commanding the U.S. Navy's Pacific Squadron, had learned of Frémont's support for the Bears in Sonoma. Sloat finally concluded on July 6 that he needed to act, "I shall be blamed for doing too little or too much - I prefer the latter."[39] Early July 7, the United States Navy, captured Monterey, California, and raised the flag of the United States. Sloat had his proclamation read and posted in English and Spanish: "...henceforth California will be a portion of the United States."[40]

The Bear Flag Revolt and whatever remained of the "California Republic" ceased to exist on July 9 when U.S. Navy Lieutenant Joseph Revere raised the United States flag in front of the Sonoma Barracks and sent a second flag to be raised at Sutter's Fort.[41]

Early American period

Until May 26, 1848, when Mexico and the United States ratified the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Alta California was officially militarily-occupied enemy territory. Until a civilian authority was established the military decided to retain the Mexican administrative and judicial system of prefects for districts and alcaldes for municipalities.[42] This continued even after California became part of the United States because Congress never did organize California as a U. S. territory. California remained a military district so the old Mexican laws, supplemented by pronouncements of the military governors, largely remained in place. California finally did achieve statehood on September 9, 1850, as part of the slavery-focused Compromise of 1850.

Sonoma Barracks

Company B of the California Battalion, that had been left in Sonoma for the protection of the town, was soon placed under U.S. Navy command.[43] The American immigrants who comprised Company B eventually returned to their homes. Sonoma's Alcalde complained to the U.S. Navy about the lack of protection for the town and a detachment of U.S. Marines was assigned to the Sonoma Barracks.[44] In March, 1847, the Marines were replaced by Company "C" of what was called Stevenson's New York Volunteers.[45] The enlistments of the New York Volunteers ended with the war and they were replaced in May, 1849, by a 37-man company of U.S. dragoons (Company C, 1st U.S. Dragoons) who moved into the Barracks and established Camp Sonoma.[46] Sonoma was also the headquarters of the Pacific Division of the U.S. Army under Brevet Major General Persifor Smith. Sonoma lost its military population in January, 1852, when the troops moved to Benicia and other assignments in California and Oregon.[47] The Army continued to use part of the Barracks as a supply depot until August 1853.[48]

_-_Sonoma_State_Historic_Park.jpg)

Sonoma's economic activity

Local businesses prospered with the business brought by the soldiers as well as miners traveling to and from the gold fields. The prosperity and optimism about Sonoma's future promoted land speculation which was particularly problematic because of the cloudy records regarding land ownership. Vallejo had granted land by virtue of his office as Director of Colonization before the pueblo was organized. Among the traditional duties of Alta California's alcaldes was the selling of town lots. Political factions backed different Sonoma alcaldes (John H. Nash, supported by American immigrants, and Lilburn Boggs supported by Vallejo and the Californios) made the situation more complex.[49] Some property was sold more than once.[50] A valid land sale depended on proof of the seller's chain of title. Over thirty years of lawsuits were required before land owners in Sonoma were able to obtain clear titles.[51]

Statehood and loss of the county seat

California elected a civilian government (albeit by military order)[52] to organize the state before it was officially formed by the United States Congress in 1850. Sonoma was named the county seat for Sonoma County. About that time the flow of miners had slowed and the U.S. Army was leaving Sonoma. Business in Sonoma moved into a recession in 1851.[53] Surrounding towns such as Petaluma and Santa Rosa were developing and gaining population faster than Sonoma. An 1854 special election moved the county seat and its entailed economic activity to Santa Rosa.

Other history

Plaza

El Pueblo de Sonoma was laid out in the standard form of a Mexican town, centered around the largest plaza in California, 8 acres (32,000 m2) in size. This plaza is surrounded by many historical buildings, including the Mission San Francisco Solano, Captain Salvador Vallejo's Casa Grande, the Presidio of Sonoma, the Blue Wing Inn, the Sebastiani Theatre, and the Toscano Hotel. In the middle of the plaza, Sonoma's early 20th-century city hall, at the plaza's center and still in use, was designed and built with four identical sides in order not to offend the merchants on any one side of the plaza. The plaza is a National Historic Landmark and still serves as the town's focal point, hosting many community festivals and drawing tourists all year round. In the 1920s, a local election was held to determine if a gasoline service station should be built on the South-East corner of the Plaza. It was defeated. There are approximately thirty restaurants in the plaza area, including Italian, Irish, Mexican, Portuguese, Basque, Mediterranean, Himalayan, and French. It provides a central tourist attraction. It is also the location of the Farmer's Market, held every Tuesday evening from April to October. In 2015, the town was named a Preserve America Community.[54]

20th century

The United States Navy operated a rest center at the Mission Inn through World War II.[55] Parts of Wes Craven's Scream (1996) was filmed in the city, with shots of the Sonoma Community Center masked as Westboro High School.[56]

Viticulture

Sonoma is also considered the birthplace of wine-making in California, dating back to the original vineyards of Mission San Francisco Solano, with improvements made by Agoston Haraszthy, the father of California viticulture and credited with introduction of the Zinfandel/Primitivo grape varietal. The Valley of the Moon Vintage Festival takes place late each September, and is California's oldest celebration of its winemaking heritage. Many residents of Sonoma are third- or fourth-generation German-Americans, Italian-Americans, Portuguese-Americans, Spanish-Americans, and French-Americans, descendants of immigrants who came to the area to work in wine-making.

Geography

The city is situated in the Sonoma Valley, with the Mayacamas Mountains to the east and the Sonoma Mountains to the west, with the prominent landform Sears Point to the southwest.

The city has an area of 2.7 sq mi (7.0 km2), none of it covered by water.

Climate

Sonoma has a typical lowland near-coastal Californian warm-summer mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification Csb) with hot, dry summers (although nights are comfortably cool) and cool, wet winters. In January, the normal high is 57.2 °F (14.0 °C) and the typical low is 37.2 °F (2.9 °C). In July, the normal high is 88.6 °F (31.4 °C) and the normal low is 51.2 °F (10.7 °C). There are an average of 58.1 days with highs of 90 °F (32 °C) or higher and 12.1 days with highs of 100 °F (38 °C). The highest temperature on record was 116 °F (47 °C) on July 13, 1972, and the lowest temperature was 13 °F (−11 °C) on December 22, 1990. Normal annual precipitation is 29.43 inches (748 mm). The wettest month on record was 20.29 inches (515 mm) in January 1995. The greatest 24-hour rainfall was 6.75 inches (171 mm) on January 4, 1982. There are an average of 68.6 days with measurable precipitation. Snow has rarely fallen, but 1.0 inch fell in January 1907; more recently, snow flurries were observed on February 5, 1976 and in the winter of 2001.[57]

| Climate data for Sonoma, California | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 84 (29) |

84 (29) |

90 (32) |

100 (38) |

105 (41) |

112 (44) |

116 (47) |

107 (42) |

110 (43) |

107 (42) |

91 (33) |

80 (27) |

116 (47) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 57.2 (14.0) |

63.2 (17.3) |

66.4 (19.1) |

71.2 (21.8) |

77.2 (25.1) |

84.1 (28.9) |

88.6 (31.4) |

88.2 (31.2) |

86.3 (30.2) |

78.6 (25.9) |

65.9 (18.8) |

57.5 (14.2) |

73.7 (23.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 47.2 (8.4) |

51.5 (10.8) |

53.6 (12.0) |

56.7 (13.7) |

61.6 (16.4) |

66.9 (19.4) |

69.9 (21.1) |

69.5 (20.8) |

67.8 (19.9) |

62.0 (16.7) |

53.3 (11.8) |

47.3 (8.5) |

58.9 (15.0) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 37.2 (2.9) |

39.9 (4.4) |

40.8 (4.9) |

42.3 (5.7) |

46.0 (7.8) |

49.7 (9.8) |

51.2 (10.7) |

50.8 (10.4) |

49.3 (9.6) |

45.5 (7.5) |

40.6 (4.8) |

37.1 (2.8) |

44.2 (6.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 20 (−7) |

20 (−7) |

24 (−4) |

20 (−7) |

27 (−3) |

31 (−1) |

35 (2) |

36 (2) |

34 (1) |

30 (−1) |

22 (−6) |

13 (−11) |

13 (−11) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 6.14 (156) |

5.27 (134) |

4.05 (103) |

1.77 (45) |

0.82 (21) |

0.23 (5.8) |

0.03 (0.76) |

0.08 (2.0) |

0.33 (8.4) |

1.67 (42) |

3.85 (98) |

5.18 (132) |

29.42 (747.96) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11 | 10 | 10 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 8 | 11 | 65 |

| Source: Western Regional Climate Center (normals and extremes 1893–present)[57] | |||||||||||||

Environmental features

The principal watercourse in the town is Sonoma Creek, which flows in a southerly direction to discharge ultimately to the Napa Sonoma Marsh; Arroyo Seco Creek is a tributary to Schell Creek with a confluence in the eastern portion of the town. The active Rodgers Fault lies to the west of Sonoma Creek; however, risk of major damage is mitigated by the fact that most of the soils beneath the city consist of a slight alluvial terrace underlain by strongly cemented sedimentary and volcanic rock.[58] To the immediate south, west and east are deeper rich, alluvial soils that support valuable agricultural cultivation. The mountain block to the north rises to 1,200 feet (366 m) and provides an important scenic backdrop, around which views the city's original streetscape was carefully laid out.

In terms of fauna, there are a variety of birds, small mammals and amphibians which reside in Sonoma. California quail frequent the riparian areas, while black tailed deer kite, duck, swan, hummingbird, goose, towhee, waxwing, great blue heron, many egret, ibis and hawk, gull, tern, robin, thrush and sparrow species are found locally. Deer, mountain lions, and many small mammals are found locally as well.

The town of Sonoma boasts a relatively quiet setting, with California State Route 12 (called from north to south Sonoma Highway, West Napa Street, and Broadway), Fifth Street West, and Spain Street being the primary noise sources. About eight miles (13 km) south of the city is Sonoma Raceway, which is also a significant noise generator. The total citywide population exposed to environmental noise exceeding 60 CNEL is approximately 300.

Demographics

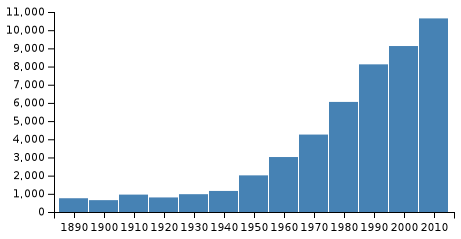

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1890 | 757 | — | |

| 1900 | 652 | −13.9% | |

| 1910 | 957 | 46.8% | |

| 1920 | 801 | −16.3% | |

| 1930 | 980 | 22.3% | |

| 1940 | 1,158 | 18.2% | |

| 1950 | 2,015 | 74.0% | |

| 1960 | 3,023 | 50.0% | |

| 1970 | 4,259 | 40.9% | |

| 1980 | 6,054 | 42.1% | |

| 1990 | 8,121 | 34.1% | |

| 2000 | 9,128 | 12.4% | |

| 2010 | 10,648 | 16.7% | |

| Est. 2019 | 11,024 | [9] | 3.5% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[59] | |||

2010

The 2010 United States Census[60] reported that Sonoma had a population of 10,648. The population density was 3,883.3 people per square mile (1,499.4/km2). The racial makeup of Sonoma was 9,242 (86.8%) White, 52 (0.5%) African American, 56 (0.5%) Native American, 300 (2.8%) Asian, 23 (0.2%) Pacific Islander, 711 (6.7%) from other races, and 264 (2.5%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1,634 persons (15.3%).

Within the Sonoma Valley, the racial makeup was 46.3% White, 49.1% Hispanic, and 2.7% Native American

Average Household Income: 96,722

Per capita income: $33,245

Median Age: 41.6

Percent under age 20: 24%

Percent age 20-64: 58%

Percent age 65+: 18%

The Census reported that 10,411 people (97.8% of the population) lived in households, 11 (0.1%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 226 (2.1%) were institutionalized.

There were 4,955 households, out of which 1,135 (22.9%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 2,094 (42.3%) were married couples living together, 425 (8.6%) had a female householder with no husband present, 174 (3.5%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 230 (4.6%) unmarried partnerships, and 48 (1.0%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 1,920 households (38.7%) were made up of individuals, and 1,054 (21.3%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.10. There were 2,693 families (54.3% of all households); the average family size was 2.82.

The population was spread out, with 1,920 people (18.0%) under the age of 18, 559 people (5.2%) aged 18 to 24, 2,252 people (21.1%) aged 25 to 44, 3,250 people (30.5%) aged 45 to 64, and 2,667 people (25.0%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 49.2 years. For every 100 females, there were 83.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 78.8 males.

There were 5,544 housing units at an average density of 2,021.9 per square mile (780.7/km2), of which 2,928 (59.1%) were owner-occupied, and 2,027 (40.9%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 2.6%; the rental vacancy rate was 7.0%. 6,294 people (59.1% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 4,117 people (38.7%) lived in rental housing units.

2000

At the previous census[11] of 2000, there were 9,128 people, 4,373 households, and 2,361 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,442/sq mi (1,330/km2). There were 4,671 housing units at an average density of 1,762/sq mi (681/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 93.80% White, 0.36% African American, 0.34% Native American, 1.70% Asian, 0.05% Pacific Islander, 1.61% from other races, and 2.14% from two or more races. 6.85% of the population were Hispanics (of any race).

There were 4,373 households, of which 21.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 42.5% were married couples living together, 8.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 46.0% were non-families. 39.2% of households consisted of individuals, and 21.5% had someone living alone who was 65 or older. The average household size was 2.07 and the average family size was 2.77. The age distribution was as follows: 18.6% under the age of 18, 4.8% from 18 to 24, 23.5% from 25 to 44, 28.9% from 45 to 64, and 24.2% who had achieved age 65. The median age was 47 years. For every 100 females, there were 81.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 77.0 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $50,505, and the median income for a family was $65,600. Males had a median income of $51,831 versus $40,276 for females. The per capita income for the city was $32,387. 3.7% of the population and 2.0% of families were below the poverty line. 3.3% of those under 18 and 4.7% of those were 65 and older.

Government

The City of Sonoma was incorporated on September 3, 1883.[2] It uses a council–manager form of government, wherein a council sets policy and hires staff to implement it. The city council has five members, elected to four-year terms.[3] The city council selects one of its members to serve as mayor:

- In 2007 the mayor was Stanley Cohen[61]

- In December 2014 the mayor was David Cook.[62]

- In 2016 the mayor was Rachel Hundley[63]

- In 2018 the mayor was Madolyn Agrimonti[64][65]

- In 2019 the mayor is Amy Harrington[66]

In addition to the official mayor, Sonoma has a tradition of naming an honorary mayor each year, titled "Alcalde/Alcaldessa".[67] Alcalde or Alcaldessa presides over ceremonial events for the city. This honor was bestowed upon: Al and Kathy Mazza (Alcalde and Alcaldessa, 2006), [68] Elizabeth Kemp(2009),[67] Mary Evelyn Arnold (2011),[69] Les and Judy Vadasz, (Alcalde and Alcaldessa, 2013),[70]

State and federal representation

In the California State Legislature, Sonoma is in the 3rd Senate District, represented by Democrat Bill Dodd, and in the 10th Assembly District, represented by Democrat Marc Levine.[71]

In the United States House of Representatives, Sonoma is in California's 5th congressional district, represented by Democrat Mike Thompson.[72]

According to the California Secretary of State, as of February 10, 2019, Sonoma has 7,162 registered voters. Of those, 3,694 (51.6%) are registered Democrats, 1,309 (18.3%) are registered Republicans, and 1,783 (24.9%) have declined to state a political party.[73]

Media

The two primary news sources for Sonoma are the Sonoma Index-Tribune and the Sonoma Valley Sun. The Sonoma Index-Tribune publishes twice weekly on Tuesdays and Fridays and has a circulation of 9,000. The Sonoma Valley Sun publishes every two weeks on Thursdays and is free. The Sun is recognized as the alternative weekly for the Sonoma Valley. It has a circulation of 5,000. Sonoma has a local radio station, KSVY and a television station, SVTV 27.

Transportation

California State Route 12 is the main route in Sonoma, passing through the populated areas of the Sonoma Valley and connecting it to Santa Rosa to the north and Napa to the east. State routes 121 and 116 run to the south of town, passing through the unincorporated area of Schellville and connecting Sonoma Valley to Napa, Petaluma to the west, and Marin County to the south. Sonoma County Transit provides bus service from Sonoma to other points in the county. VINE Transit also operates a route between Napa and Sonoma.

The nearest airport with regularly scheduled commercial passenger service is Charles M. Schulz–Sonoma County Airport, about 30 miles (50 km) northwest of Sonoma. San Francisco International Airport and Oakland International Airport are both about 60 miles (100 km) south of Sonoma.

Notable people

- Hap Arnold was an aviation pioneer and commander of the United States Army Air Corps (from 1938), commander of the U.S. Army Air Forces (from 1941 until 1945) and the first General of the Air Force (in 1949). The main arterial road, Arnold Drive, which runs up the west side of Sonoma Valley, is named for him, as was Arnold Field, a Baseball field in downtown Sonoma.

- Phil Coturri, a viticulturalist who is recognized as pioneering organic and biodynamic

- Count Agoston Haraszthy, the father of California viticulture, created the first winery west of the Mississippi. He tried many locations but settled in Sonoma with General Vallejo's assistance. His first winery, Buena Vista, still exists today.

- Joseph Hooker, one-time politician and future American Civil War general, lived in Sonoma in the 1850s. His house still exists in town.

- Kirk Hammett (born November 18, 1962) is lead guitarist and a songwriter in the heavy metal band Metallica.

- John Lasseter (born January 12, 1957 in Hollywood, California) is an animator and the chief creative executive at Pixar Animation Studios. Lasseter won Academy Awards for Best Animated Short Film (Tin Toy) and Special Achievement Award (Toy Story). Lasseter and his family reside in the Sonoma Valley area of the city.

- Thornton Lee (1906–1997), an All-Star pitcher in Major League Baseball, was born in Sonoma.

- Professional athletes Tommy Everidge and Tony Moll were classmates, and grew up in Sonoma.

- Brian Posehn, comedian and co-star on The Sarah Silverman Program, grew up in Sonoma.

- Sebastiani Family: family patriarch Samuele Sebastiani started Sebastiani Vineyards in 1904. His son August ran the company from 1944 to the late 1970s, when his son Sam took the reins. August died in 1980. In 1986, August's youngest son, Don Sebastiani, took the company from about 200,000 cases to just shy of 8 million cases produced in 1999, at which time he sold a number of assets to Constellation Wines. Don then left the old family company and he, along with his sons, Donny and August, started Don Sebastiani & Sons in 2000. Sebastiani Vineyards was under the direction of Sam and Don's sister, Mary Ann Sebastiani Cuneo, before being sold to the Foley Wine Group in 2008. Don's son, August Sebastiani, was elected to the Sonoma City Council in 2006.

- Tim Schafer, an American computer game designer and founder of Double Fine Productions. He is best known as the designer of critically acclaimed games Full Throttle, Grim Fandango, Psychonauts, Brütal Legend and Broken Age, co-designer of Day of the Tentacle, and assistant designer on The Secret of Monkey Island and Monkey Island 2: LeChuck's Revenge.

- William Smith (1768-1846), only American Revolutionary War veteran believed to be buried in California

- Tom Smothers (born Thomas Bolyn Smothers III on February 2, 1937) is a comedian, composer and musician, best known as half of the musical comedy team The Smothers Brothers, alongside his younger brother Dick. They currently operate the Remick Ridge Vineyards in the Sonoma Valley.

- Chuck Williams: founder of Williams Sonoma, the food accessory chain store, started its existence on Broadway, two blocks from the Plaza, before moving to San Francisco.

- Paula Wolfert (born 1938 in Brooklyn, New York), award-winning author of eight cookbooks, and her husband William Bayer (born 1939 in Cleveland, Ohio), award-winning crime fiction writer, have been resident in Sonoma since 1998.

- Ignazio Vella (1928–2011) ran the Vella Cheese Company for many years and also served three terms on the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors.

- Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo was the last Mexican military commander of northern California. His residence in Sonoma was the site for a portion of the Bear Flag revolt which made California a Republic.

- Jayce Ray, professional baseball player for the Sussex County Miners. Spent 2016 in the Boston Red Sox minor league system.

See also

Historic sites

Sonoma can boast three of the first ten California Historical Landmarks:

- Mission San Francisco Solano (#3) - On July 4, 1823, Padre José Altamira founded the northernmost of California's Franciscan missions here, the only one established in California under independent Mexico.

- The home of General Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo (#4) - known as Lachryma Montis (Tears of the Mountain), was built in 1850.

- Bear Flag Monument (#7) - On June 14, 1846, the Bear Flag Party raised the Bear Flag in the Sonoma plaza and declared California free from Mexican rule.

- The Presidio of Sonoma, the northernmost Mexican military post, still stands facing the plaza.

The city has established about 90 city historic landmarks.

Items named after the town

- Sonoma Jack Cheese: Cheese, moist to very dry light colored cheese covered in chocolate powder and most credited to the Vella cheese making family. The Vella Cheese factory, former Sonoma Brewing Co. building, continues to make a variety of cheese products.

- The GMC Sonoma was a compact pickup truck.

- Intel's "Sonoma" series processors. Several of Intel's processors were given names from towns, cities or places in Sonoma County when Intel's CEO was Les Vadasz. He is a resident of the Valley of the Moon area.

Restaurants

- Cafe La Haye

- the girl & the fig

- [Valley Bar & Bottle]

Wineries

Additional points of interest

- Sonoma Stompers independent professional baseball team.

- Sonoma Cheese Factory

- Sonoma Creek

- Sonoma Skatepark

- Arroyo Seco Creek

- Jack London State Historic Park

- Quarryhill Botanic Garden

- Sonoma Valley

- Sonoma Developmental Center

- Sonoma TrainTown Railroad - a quarter scale train in a park 1-mile (1.6 km) south of the Town Square that covers 10 acres (40,000 m2). It has a petting zoo, ferris wheel, swings, vintage carousel, scrambler, miniature coaster and an airplane ride. In a television commercial, Train Town has claimed to be one fifth the size of the original Disneyland and twice the fun. It was opened in 1968. The airplane ride is only for children that are 54 inches (1,400 mm) tall or shorter, so it does have a height restriction.

- Sonoma Plaza

- Blue Wing Inn of 1840, where notable guests, according to local tradition, included John C. Frémont, U. S. Grant, Governor Pío Pico, Kit Carson, Fighting Joe Hooker, William T. Sherman, Phil Sheridan, and members of the Bear Flag Party.

- General Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo Home: official residence of the last Mexican Governor.

- Presidio of Sonoma adobe

- Mission San Francisco Solano, California's last Mission

- Sebastiani Theatre - a historical theatre built in 1933 by Samuele Sebastiani as a movie house.

- Sonoma Raceway

- The Sonoma Overlook Trail

- Microsoft Windows Bliss (image) was photographed southeast of town on Fremont Drive near the site of Stornetta's Dairy.

Sister cities of Sonoma

Notes

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on November 3, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- "City Council Overview". City of Sonoma. Archived from the original on December 8, 2012. Retrieved January 24, 2015.

- "Amy Harrington". Archived from the original on February 20, 2019. Retrieved February 19, 2019.

- "City Manager - City of Sonoma". Archived from the original on February 20, 2019. Retrieved February 19, 2019.

- "2016 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- "Sonoma". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- "Sonoma (city) QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved April 12, 2015.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "American FactFinder - Results". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- SSHP-GP p.11

- S/PSHPA

- CIMCC

- Bancroft p. 496

- Smilie p. 34

- Bancroft III:720

- Bancroft 3:246

- Smilie p.54

- Stammerjohan p.25

- Smilie p. 50

- Bancroft III:721

- Bancroft IV: 678 note 16

- Bancroft; IV: 598-608

- Richman p 308

- Hague p.118

- Ide p. 112-3

- Bancroft V:109

- Harlow p.98-99

- Harlow p. 102

- Walker p. 125-6

- Bancroft V:117

- SSHP-GP p. 82

- Harlow p, 108-110

- Walker p. 134-5

- Bancroft V:178-80

- Bancroft V:184-5

- Harlow p. 121

- Harlow p. 122

- Harlow p. 124

- Bancroft V:185-86

- Bancroft VI:257-258

- Parmelee p. 40

- Stammerjohan p.59

- Stammerjohan p.63

- SSHP-GP p.15

- Alexander p.26

- SSHP-GP p.82

- Parmelee p. 90-93

- Bancroft V:668-670

- Parmelee p. 94

- Bancroft VI:275

- Parmelee p. 101

- "Sonoma named national 'Preserve America Community'". What's Happening. Sonoma Valley Sun. August 11, 2015. Archived from the original on August 15, 2015. Retrieved August 14, 2015.

- "U.S. Naval Activities World War II by State". Patrick Clancey. Archived from the original on September 7, 2011. Retrieved March 19, 2012.

- Daniel Farrands (Director) Thommy Hutson (Writer) (April 6, 2011). Scream: The Inside Story (TV). United States: The Biography Channel Video.

- "General Climate Summary Tables - Sonoma, California". Western Regional Climate Center. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- General Plan, City of Sonoma, California, prepared for the City of Sonoma by Hall and Goodhue Community Design Group, San Francisco, Ca. (1974)

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - Sonoma city". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 11, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ".:: City of Sonoma". Archived from the original on August 10, 2007.

- ".:: City of Sonoma". Archived from the original on December 30, 2014.

- Clark Mason (December 18, 2016). "From a food truck to City Hall: Get to know Sonoma's new mayor". Press Democrat. Archived from the original on August 29, 2018. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- "City Council - City of Sonoma". Archived from the original on August 29, 2018.

- Julie Vader (December 13, 2018). "Amy Harrington is Sonoma's new Mayor". Sonoma Index-Tribune. Archived from the original on February 20, 2019. Retrieved February 19, 2019.

- Carole Kelleher (January 28, 2019). "Meet the Mayor: Amy Harrington has firm grip on the gavel". Sonoma Index-Tribune. Archived from the original on February 20, 2019. Retrieved February 19, 2019.

- "Recognizing Alcaldessa Elizabeth Kemp Of Sonoma, California". Archived from the original on September 20, 2014. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- "Recognizing Al And Kathy Mazza Of Sonoma, California". Archived from the original on September 18, 2014. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- Statement Recognizing Mary Evelyn Arnold, Alcaldessa for the City of Sonoma's Archived December 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Les and Judy Vadasz Are Alcalde and Alcaldessa for 2013 Archived January 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- "California's 5th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- "CA Secretary of State – Report of Registration – February 10, 2019" (PDF). ca.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 23, 2019. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

References

- Alexander, James B. (1986). Sonoma Valley Legacy. Sonoma, CA: Sonoma Valley Historical Society.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1886). History of California Vol. II-V. The History Company, San Francisco, CA.

- CIMCC. "San Francisco de Solano - General Information". California Indian Museum and Cultural Center. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- Court of Claims (United States). "Mariano G Vallejo vs. The United States". Case 566.

- CSMM, The California State Military Museum. "Captain John Charles Fremont and the Bear Flag Revolt". Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- Fremont, John Charles; Fremont, Jessie Benton (1887). Memoirs of My Life, Vol. 1. Belford, Clarke.

- Hague, Harlan & David J. Langum Thomas O. Larkin: A Life of Patriotism and Profit in Old California, University of Oklahoma Press, (1990)

- Harlow, Neal California Conquered: The Annexation of a Mexican Province 1846–1850, ISBN 0-520-06605-7, (1982)

- Parmelee, Robert D (1972). Pioneer Sonoma. Sonoma, CA: The Sonoma Valley Historical Society.

- Richman, Irving B. (1911). California Under Spain and Mexico, 1535-1847. The Riverside Press, Cambridge.

- Smilie, Robert A. (1975). The Sonoma Mission, San Francisco Solano de Sonoma: The Founding, Ruin and Restoration of California's 21st Mission. Valley Publishers, Fresno, CA. ISBN 978-0-913548-24-0.

- S/PSHPA - Sonoma/Petaluma State Historic Parks Association. "Mission San Francisco Solano". Retrieved April 12, 2014.

- SSHP. "Sonoma State Historic Park - A Short History of Historical Archaeology". California Department of Parks and Recreation. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- SSHP-GP. "Sonoma State Historic Park - General Plan" (PDF). California Department of Parks and Recreation. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- Stammerjohan, George. Sonoma Barracks, A Military View. Department of Parks and Recreation, State of California.

- Walker, Dale L. (1999). Bear Flag Rising: The Conquest of California, 1846. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0312866853.