Sardar Sarovar Dam

The Sardar Sarovar Dam is a concrete gravity dam on the Narmada river in Kevadiya near Navagam, Gujarat in India. Four Indian states, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Rajasthan, receive water and electricity supplied from the dam. The foundation stone of the project was laid out by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru on 5 April 1961. The project took form in 1979 as part of a development scheme funded by the World Bank through their International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, to increase irrigation and produce hydroelectricity, using a loan of US$200 million.[3] The construction for dam begun in 1987, but the project was stalled by the Supreme Court of India in 1995 in the backdrop of Narmada Bachao Andolan over concerns of displacement of people. In 2000–01 the project was revived but with a lower height of 110.64 metres under directions from SC, which was later increased in 2006 to 121.92 meters and 138.98 meters in 2017.[4] The water level in the Sardar Sarovar Dam at Kevadia in Narmada district reached its highest capacity at 138.68 metres on 15 September 2019.[5][6]

| Sardar Sarovar Dam | |

|---|---|

The Sardar Sarovar Dam on Narmada River | |

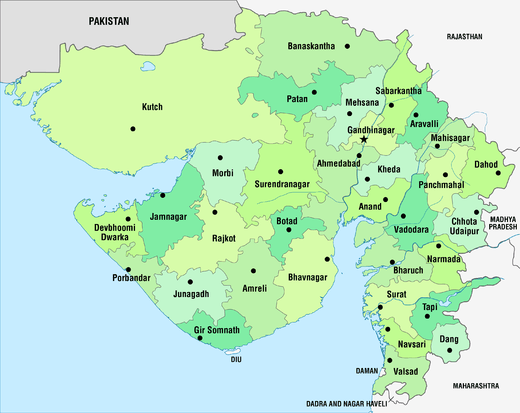

Location of Sardar Sarovar Dam in Gujarat | |

| Official name | Narmada valley |

| Country | India |

| Location | Navagam, Kevadiya Colony, India |

| Coordinates | 21°49′49″N 73°44′50″E |

| Status | Operational |

| Construction began | April 1987 |

| Opening date | 17 September 2017 |

| Construction cost | ₹.25 billion INR |

| Owner(s) | Gujarat,Madhya Pradesh,Maharashtra,Rajasthan. |

| Dam and spillways | |

| Type of dam | gravity dam, |

| Impounds | Narmada River |

| Height | 138.68 meters |

| Height (foundation) | 163 m (535 ft) |

| Length | 1,210 m (3,970 ft) |

| Spillway capacity | 84,949 m3/s (2,999,900 cu ft/s) |

| Reservoir | |

| Total capacity | 9.5 km3 (7,700,000 acre⋅ft) |

| Active capacity | 5.8 km3 (4,700,000 acre⋅ft) |

| Catchment area | 88,000 km2 (34,000 sq mi) |

| Surface area | 375.33 km2 (144.92 sq mi) |

| Maximum length | 214 km (133 mi) |

| Maximum width | 1.77 km (1.10 mi) |

| Maximum water depth | 140m |

| Normal elevation | 138 m (453 ft) |

| Power Station | |

| Operator(s) | Sardar Sarovar Narmada Nigam Limited[1] |

| Commission date | June 2006 |

| Turbines | Dam: 6 × 200 MW Francis pump-turbine Canal: 5 × 50 MW Kaplan-type[2] |

| Installed capacity | 1,450 MW [1 Billion kWh every year] |

| Website www | |

One of the 30 dams planned on river Narmada, Sardar Sarovar Dam (SSD) is the largest structure to be built. It is the second largest concrete dam in the world in terms of the volume of concrete used to construct dam after the Grand Coulee dam across River Columbia, US..[7][8] It is a part of the Narmada Valley Project, a large hydraulic engineering project involving the construction of a series of large irrigation and hydroelectric multi-purpose dams on the Narmada river. Following a number of controversial cases before the Supreme Court of India (1999, 2000, 2003), by 2014 the Narmada Control Authority had approved a series of changes in the final height – and the associated displacement caused by the increased reservoir, from the original 80 m (260 ft) to a final 163 m (535 ft) from foundation.[9][10] The project will irrigate more than 18,000 km2 (6,900 sq mi), most of it in drought prone areas of Kutch and Saurashtra.

The dam's main power plant houses six 200 MW Francis pump-turbines to generate electricity and include a pumped-storage capability. Additionally, a power plant on the intake for the main canal contains five 50 MW Kaplan turbine-generators. The total installed capacity of the power facilities is 1,450 MW.[11]

Geographical location

To the south west Malwa plateau, the dissected hill tracts culminate in the Mathwar hills, located in Alirajpur district of Madhya Pradesh. Below these hills Narmada river flows through a long, terrific gorge. This gorge extends into Gujarat where the river is tapped by the Sardar Sarovar dam.

Narmada Canal

The dam irrigates 17,920 km2 (6,920 sq mi) of land spread over 12 districts, 62 talukas, and 3,393 villages (75% of which is drought-prone areas) in Gujarat and 730 km2 (280 sq mi) in the arid areas of Barmer and Jalore districts of Rajasthan. The dam also provides flood protection to riverine reaches measuring 30,000 ha (74,000 acres) covering 210 villages and Bharuch city and a population of 400,000 in Gujarat.[12] Saurashtra Narmada Avtaran Irrigation is a major program to help irrigate a lot of regions using the canal's water.

Solar power generation

In 2011, the government of Gujarat announced plans to generate solar power by placing solar panels over the canal, making it beneficial for the surrounding villages to get power and also help to reduce the evaporation of water. The first phase consists of placing panels along a 25 km length of the canal, with capacity for up to, 25 MW of power.[13]

Controversy

The dam is one of India's most controversial, and its environmental impact and net costs and benefits are widely debated.[14][15][16] The World Bank was initially funding SSD, but withdrew in 1994 at the request of the Government of India when the state governments were unable to comply with the loan's environmental and other requirements.[17] The Narmada Dam has been the centre of controversy and protests since the late 1980s.[18]

One such protest takes centre stage in the Spanner Films documentary Drowned Out (2002), which follows one tribal family who decide to stay at home and drown rather than make way for the Narmada Dam.[19] An earlier documentary film is called A Narmada Diary (1995) by Anand Patwardhan and Simantini Dhuru. The efforts of Narmada Bachao Andolan ("Save Narmada Movement") to seek "social and environmental justice" for those most directly affected by the Sardar Sarovar Dam construction feature prominently in this film. It received the (Filmfare Award for Best Documentary-1996).[20]

The figurehead of much of the protest is Medha Patkar, the leader of the NBA[21] The movement was cemented in 1989, and received the Right Livelihood Award in 1991.

In an opinion piece in The Guardian, the campaign led by the NBA activists was accused of holding up the project's completion and of even physically attacking local people who accepted compensation for moving.[14]

Support for the protests also came from Indian author Arundhati Roy, who wrote "The Greater Common Good", an essay reprinted in her book The Cost of Living, in protest of the Narmada Dam Project.[22] In the essay, Roy states:

Big Dams are to a Nation's "Development" what Nuclear Bombs are to its Military Arsenal. They are both weapons of mass destruction. They're both weapons Governments use to control their own people. Both Twentieth Century emblems that mark a point in time when human intelligence has outstripped its own instinct for survival. They're both malignant indications of civilisation turning upon itself. They represent the severing of the link, not just the link—the understanding—between human beings and the planet they live on. They scramble the intelligence that connects eggs to hens, milk to cows, food to forests, water to rivers, air to life and the earth to human existence.

Height increases

undergoing height increase in 2006.

- In February 1999, the Supreme Court of India gave the go ahead for the dam's height to be raised to 88 m (289 ft) from the initial 80 m (260 ft).

- In October 2000 again, in a 2-to-1 majority judgment in the Supreme Court, the government was allowed to construct the dam up to 90 m (300 ft).[9]

- In May 2002, the Narmada Control Authority approved increasing the height of the dam to 95 m (312 ft).

- In March 2004, the Authority allowed a 15 m (49 ft) height increase to 110 m (360 ft).

- In March 2006, the Narmada Control Authority gave clearance for the height of the dam to be increased from 110.64 m (363.0 ft) to 121.92 m (400.0 ft). This came after 2003 when the Supreme Court of India refused allow the height of the dam to increase again.

- In August 2013, heavy rains raised the reservoir level to 131.5 m (431 ft), which forced 7,000 villagers upstream along the Narmada River to relocate.[23]

- On June 2014, Narmada Control Authority gave the final clearance to raise the height from 121.92 m (400.0 ft) metres to 138.68 m (455.0 ft)[24]

- The Narmada Control Authority decided on 17 June 2017 to raise the height of the Sardar Sarovar Dam to its fullest height 163-meter by ordering the closure of 30 Gates

Report of the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF)

The Second Interim Report of the Experts' Committee set up by the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) of the Government of India to assess the planning and implementation of environmental safeguards with respect to the Sardar Sarovar (SSP) and Indira Sagar projects (ISP) on the Narmada River. The report covers the status of compliances on catchment area treatment (CAT), flora and fauna and carrying capacity upstream, command area development (CAD), compensatory afforestation and human health aspects in project impact areas. Construction, on the other hand, has been proceeding apace: the ISP is complete and the SSP nearing completion. The report recommends that no further reservoir-filling be done at either SSP or ISP; that no further work be done on canal construction; and that even irrigation from the existing network be stopped forthwith until failures of compliance on the various environmental parameters have been fully remedied.[25]

Notes

- "The Sardar Sarovar Project". Sardar Sarovar Narmada Nigam Ltd. Needs better citation.

- "Pumped-Storage Hydroelectric Plants — Asia-Pacific". IndustCards. Archived from the original on 8 December 2012. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- Original report – Narmada dam development project (PDF). Washington DC: World Bank. 6 February 1985. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- https://indianexpress.com/article/india/sardar-sarovar-dam-years-of-dispute-finally-full-height-narmada-river-narendra-modi-4848513/

- "Sardar Sarovar dam water level touches its highest mark". The Economic Times. 15 September 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "Sardar Sarovar Dam Water Level Touches its Highest Mark, PM Modi to Visit Site on Sept 17". News18. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "PM Modi to inaugurate world's second biggest dam on September 17". The Indian Express. Indo-Asian News Service. 14 September 2017. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- "Narendra Modi inaugurates Sardar Sarovar Dam". Al Jazeera. 17 September 2017. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- "BBC News — SOUTH ASIA — Go-ahead for India dam project". BBC.

- "Sardar Sarovar Power Complex". Narmada Control Authority. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- "World bank projects in India – Narmada development". World Bank. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019.

- "Main Features of the Dam". supportnarmadadam.org. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- "Soon, solar power panels on Narmada canal:Modi". dna.

- Leech, Kirk (3 March 2009). "The Narmada Dambusters are wrong". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 March 2009.

- Verghese, Boobli George (30 November 2000). "The verdict and after". DownToEarth. Archived from the original on 12 November 2017.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Patkar, Medha (15 June 2017). "Politics Over Narmada, Once Again". The Wire. Archived from the original on 10 July 2019.

- World Bank (1995). "Annex 2: Government Cancellation of Bank Loan". Project Completion Report: India: Narmada River Development — Gujarat: Sardar Sarovar Dam and Power Project: Annexes to Part I, and Part III. p. 148 (page 23 of 61 of Annex 2).

- Scudder, Thayer (2003), India’s Sardar Sarovar Project (SSP) (PDF), unpublished manuscript, archived (PDF) from the original on 27 May 2020

- "Drowned Out: The first 10 minutes of Drowned Out". OneWorldTV. 28 July 2009.

- "A Narmada Diary". Archived from the original on 21 February 2008. Retrieved 13 June 2008.

- Friends of River Narmada. Retrieved 9 July 2007 The Sardar Sarovar Dam: a Brief Introduction

- Roy, Arundhati (April 1999). "The Greater Common Good". Friends of River Narmada. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- "7000 villagers relocated after water level in Narmada dam crosses 130m". Express News Service. 25 August 2013. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- "NCA permits raising Narmada dam height after eight years". The Times of India. 12 June 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- Mahadevan Ramaswamy and Ramaswamy R. Iyer (31 March 2010). "A damaging report". The Hindu. Chennai: "Kasturi & Sons Ltd. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

References

- Sardar Sarovar Narmada Nigam. (01/2002) Retrieved 7 September 2007 Narmada for People and Environment

- Dam-Affected Resettlement in Gujarat, by Chhandasi Pandya. Retrieved 13 July 2007 Article

- "Second Interim Report of the Committee for Assessment of Survay / Studies / Planning and Implementation, of the Plans on Environmental Safeguard Measures for Sardar Sarovar & Indira Sagar Projects".

- Association for India's Development website

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Narmada Dam Project. |

- Friends of River Narmada

- Official Website of NVDA – Narmada Valley Development Authority

- Official website of Sardar Sarovar Narmada Nigam Limited

- Regularly updated news clippings about Narmada dams

- Concluding letter from Independent Review (also known as Morse Committee) constituted by World Bank in 1992 to assess Sardar Sarovar Dam Project djvu format or in pdf format.