Philippine–American War

The Philippine–American War,[11] also referred to as the Filipino–American War, the Philippine War, the Philippine Insurrection or the Tagalog Insurgency[12][13] (Filipino: Digmaang Pilipino–Amerikano; Spanish: Guerra filipino–estadounidense), was an armed conflict between the First Philippine Republic and the United States that lasted from February 4, 1899, to July 2, 1902.[1] While Filipino nationalists viewed the conflict as a continuation of the struggle for independence that began in 1896 with the Philippine Revolution, the U.S. government regarded it as an insurrection.[14] The conflict arose when the First Philippine Republic objected to the terms of the Treaty of Paris under which the United States took possession of the Philippines from Spain, ending the Spanish–American War.[15]

| Philippine–American War Digmaang Pilipino–Amerikano | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

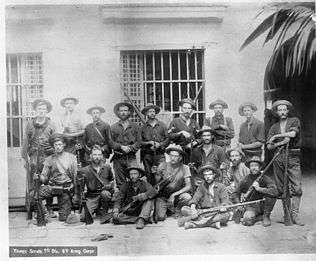

Clockwise from top left: U.S. troops in Manila, Gregorio del Pilar and his troops around 1898, Americans guarding Pasig River bridge in 1898, the Battle of Santa Cruz, Filipino soldiers at Malolos, the Battle of Quingua | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

1899–1902 |

1899–1902 | ||||||||

|

1902–1913

|

1902–1906 1899–1913 | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

1899–1902 1902–1913 |

1899–1902 1899–1913 | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| ≈24,000 to ≈44,000 field strength[5] |

≈80,000–100,000 regular and irregular[5] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 4,234[6]–6,165 killed,[7] 2,818 wounded[6] | 16,000-20,000 killed[8] | ||||||||

| Filipino civilians: 250,000–1,000,000 died, most because of famine and disease;[8] including 200,000 dead from cholera.[9][10][lower-roman 1] | |||||||||

| |||||||||

Fighting erupted between forces of the United States and those of the Philippine Republic on February 4, 1899, in what became known as the 1899 Battle of Manila. On June 2, 1899, the First Philippine Republic officially declared war against the United States.[16][17] The war officially ended on July 2, 1902, with a victory for the United States. However, some Philippine groups—led by veterans of the Katipunan, a Philippine revolutionary society—continued to battle the American forces for several more years. Among those leaders was General Macario Sakay, a veteran Katipunan member who assumed the presidency of the proclaimed Tagalog Republic, formed in 1902 after the capture of President Emilio Aguinaldo. Other groups, including the Moro, Bicol and Pulahan peoples, continued hostilities in remote areas and islands, until their final defeat at the Battle of Bud Bagsak on June 15, 1913.[18]

The war resulted in the deaths of at least 200,000 Filipino civilians, mostly due to famine and disease.[19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26] Some estimates for total civilian dead reach up to a million.[27][8] The war and especially the following occupation by the U.S., changed the culture of the islands, leading to the rise of Protestantism and disestablishment of the Catholic Church in the Philippines and the introduction of English to the islands as the primary language of government, education, business, industry and, in future decades, among upper-class families and educated individuals.

In 1902, the United States Congress passed the Philippine Organic Act, which provided for the creation of the Philippine Assembly, with members to be elected by Filipino males (women did not have the vote until after the 1937 suffrage plebiscite).[28][29] This act was superseded by the 1916 Jones Act (Philippine Autonomy Act), which contained the first formal and official declaration of the United States government's commitment to eventually grant independence to the Philippines.[30] The 1934 Tydings–McDuffie Act (Philippine Independence Act) created the Commonwealth of the Philippines the following year, increasing self-governance in advance of independence, and established a process towards full Philippine independence (originally scheduled for 1944, but interrupted and delayed by World War II). The United States granted independence in 1946, following World War II and the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, through the Treaty of Manila.

Background

Philippine Revolution

Andrés Bonifacio was a warehouseman and clerk from Manila. On July 7, 1892, he established the Katipunan—a revolutionary organization formed to gain independence from Spanish colonial rule by armed revolt. Fighters in Cavite province won early victories. One of the most influential and popular leaders from Cavite was Emilio Aguinaldo, mayor of Cavite El Viejo (modern-day Kawit), who gained control of much of the eastern portion of Cavite province. Eventually, Aguinaldo and his faction gained control of the leadership of the Katipunan movement.

After Aguinaldo was elected president of the Philippine revolutionary movement at the Tejeros Convention on March 22, 1897, his supporters had Bonifacio executed for treason after a show trial on May 10, 1897.[31] Aguinaldo is officially considered the first President of the Philippines.[32][33]

Aguinaldo's exile and return

By late 1897, after a succession of defeats for the revolutionary forces, the Spanish had regained control over most of the Philippines. Aguinaldo and Spanish Governor-General Fernando Primo de Rivera entered into armistice negotiations. On December 14, 1897, an agreement was reached in which the Spanish colonial government would pay Aguinaldo $MXN800,000[lower-alpha 1] in Manila—in three installments if Aguinaldo would go into exile outside of the Philippines.[35][36]

Upon receiving the first of the installments, Aguinaldo and 25 of his closest associates left their headquarters at Biak-na-Bato and made their way to Hong Kong, according to the terms of the agreement. Before his departure, Aguinaldo denounced the Philippine Revolution, exhorted Filipino rebel combatants to disarm, and declared those who continued hostilities and waging war to be bandits.[37] Despite Aguinaldo's denunciation, some of the revolutionaries continued their armed revolt against the Spanish colonial government.[38][39][40][41] According to Aguinaldo, the Spanish never paid the second and third installments of the agreed-upon sum.[42]

After four months in exile, Aguinaldo decided to resume his role in the Philippine Revolution. He departed from Singapore aboard the steamship Malacca on April 27, 1898. He arrived in Hong Kong on May 1,[43] the day that US Commodore George Dewey's naval forces destroyed Rear-Admiral Patricio Montojo's Spanish Pacific Squadron at the Battle of Manila Bay. Aguinaldo departed Hong Kong aboard the USRC McCulloch on May 17, arriving in Cavite on May 19.[44]

Less than three months after Aguinaldo's return, the Philippine Revolutionary Army had conquered nearly all of the Philippines. With the exception of Manila, which was surrounded by revolutionary forces some 12,000 strong, the Filipinos controlled the Philippines. Aguinaldo turned over 15,000 Spanish prisoners to the Americans, offering them valuable intelligence. Aguinaldo declared independence at his house in Cavite El Viejo on June 12, 1898.

The Philippine Declaration of Independence was not recognized by either the United States or Spain, and the Spanish government ceded the Philippines to the United States in the 1898 Treaty of Paris, which was signed on December 10, 1898, in consideration for an indemnity for Spanish expenses and assets lost.[45]

On January 1, 1899, Aguinaldo was declared President of the Philippines—the only president of what would be later called the First Philippine Republic.[46] He later organized a congress in Malolos, Bulacan to draft a constitution.[47]

Conflict origins

On April 22, 1898, while in exile, Aguinaldo had a private meeting in Singapore with United States Consul E. Spencer Pratt, after which he decided to again take up the mantle of leadership in the Philippine Revolution.[48] According to Aguinaldo, Pratt had communicated with Commodore George Dewey (commander of the Asiatic Squadron of the United States Navy) by telegram, and passed assurances from Dewey to Aguinaldo that the United States would recognize the independence of the Philippines under the protection of the United States Navy. Pratt reportedly stated that there was no necessity for entering into a formal written agreement because the word of the Admiral and of the United States Consul were equivalent to the official word of the United States government.[49] With these assurances, Aguinaldo agreed to return to the Philippines.

Pratt later contested Aguinaldo's account of these events, and denied any "dealings of a political character" with the leader.[50] Admiral Dewey also refuted Aguinaldo's account, stating that he had promised nothing regarding the future:

From my observation of Aguinaldo and his advisers I decided that it would be unwise to co-operate with him or his adherents in an official manner. ... In short, my policy was to avoid any entangling alliance with the insurgents, while I appreciated that, pending the arrival of our troops, they might be of service.[40]

Filipino historian Teodoro Agoncillo writes of "American apostasy", saying that it was the Americans who first approached Aguinaldo in Hong Kong and Singapore to persuade him to cooperate with Dewey in wresting power from the Spanish. Conceding that Dewey may not have promised Aguinaldo American recognition and Philippine independence (Dewey had no authority to make such promises), he writes that Dewey and Aguinaldo had an informal alliance to fight a common enemy, that Dewey breached that alliance by making secret arrangements for a Spanish surrender to American forces, and that he treated Aguinaldo badly after the surrender was secured. Agoncillo concludes that the American attitude towards Aguinaldo "... showed that they came to the Philippines not as a friend, but as an enemy masking as a friend."[51]

The secret agreement made by Commodore Dewey and Brigadier General Wesley Merritt with newly arrived Spanish Governor-General Fermín Jáudenes and with his predecessor Basilio Augustín was for the Spanish forces to surrender only to the Americans, not to the Filipino revolutionaries. To save face, the Spanish surrender would take place after a mock battle in Manila which the Spanish would lose; the Filipinos would not be allowed to enter the city. On the eve of the battle, Brigadier General Thomas M. Anderson telegraphed Aguinaldo, "Do not let your troops enter Manila without the permission of the American commander. On this side of the Pasig River you will be under fire."[52] On August 13, American forces captured the city of Manila from the Spanish.[53]

Before the attack on Manila, American and Filipino forces had been allies against Spain in all but name. After the capture of Manila, Spanish and Americans were in a partnership that excluded the Filipino insurgents. Fighting between American and Filipino troops had almost broken out as the former moved in to dislodge the latter from strategic positions around Manila on the eve of the attack. Aguinaldo had been told bluntly by the Americans that his army could not participate and would be fired upon if it crossed into the city. The insurgents were infuriated at being denied triumphant entry into their own capital, but Aguinaldo bided his time. Relations continued to deteriorate, however, as it became clear to Filipinos that the Americans were in the islands to stay.[54]

On December 21, 1898, President William McKinley issued a proclamation of "benevolent assimilation, substituting the mild sway of justice and right for arbitrary rule" for "the greatest good of the governed."[55] Major General Elwell Stephen Otis—who was appointed Military Governor of the Philippines at that time—delayed its publication. On January 4, 1899, General Otis published an amended version edited so as not to convey the meanings of the terms sovereignty, protection, and right of cessation, which were present in the original version.[56] However, Brigadier General Marcus Miller—then in Iloilo City and unaware that the altered version had been published by Otis—passed a copy of the original proclamation to a Filipino official there.

The original proclamation was given by supporters to Aguinaldo who, on January 5, issued a counter-proclamation:[57]

My government cannot remain indifferent in view of such a violent and aggressive seizure of a portion of its territory by a nation which arrogated to itself the title of champion of oppressed nations. Thus it is that my government is disposed to open hostilities if the American troops attempt to take forcible possession of the Visayan islands. I denounce these acts before the world, in order that the conscience of mankind may pronounce its infallible verdict as to who are true oppressors of nations and the tormentors of mankind.[58]

In a revised proclamation issued the same day, Aguinaldo protested "most solemnly against this intrusion of the United States Government on the sovereignty of these islands".[59] Otis regarded Aguinaldo's proclamations as tantamount to war, alerting his troops and strengthening observation posts. On the other hand, Aguinaldo's proclamations energized the masses with a vigorous determination to fight what was perceived as an ally turned enemy.[59]

War

Outbreak of war

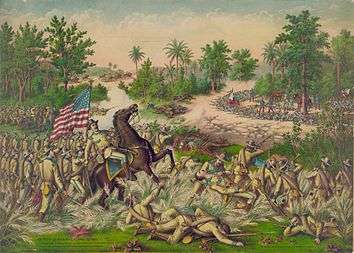

On the evening of February 4, Private William W. Grayson—a sentry of the 1st Nebraska Volunteer Infantry Regiment[60]—fired the first shots of the war at the corner of Sociego and Silencio Streets,[61] in Santa Mesa. Upon opening fire, Grayson killed a Filipino lieutenant and another Filipino soldier;[60] Filipino historians maintain that the slain soldiers were unarmed.[62] This action triggered the 1899 Battle of Manila. The following day, Filipino General Isidoro Torres came through the lines under a flag of truce to deliver a message from Aguinaldo to General Otis that the fighting had begun accidentally, and that Aguinaldo wished for the hostilities to cease immediately and for the establishment of a neutral zone between the two opposing forces. Otis dismissed these overtures, and replied that the "fighting, having begun, must go on to the grim end".[63] On February 5, General Arthur MacArthur ordered his troops to advance against Filipino troops, beginning a full-scale armed clash.[64] The first Filipino fatality of the war was Corporal Anastacio Felix of the 4th Company, Morong Battalion under Captain Serapio Narváez. The battalion commander was Colonel Luciano San Miguel.

American war strategy

Annexation of the Philippines by the United States was justified by those in the U.S. government and media in the name of liberating and protecting the peoples in the former Spanish colonies. Senator Albert J. Beveridge, one of the most prominent American imperialists at the time, said: "Americans altruistically went to war with Spain to liberate Cubans, Puerto Ricans, and Filipinos from their tyrannical yoke. If they lingered on too long in the Philippines, it was to protect the Filipinos from European predators waiting in the wings for an American withdrawal and to tutor them in American-style democracy."[65]

On February 11, 1899—one week after the first shots of the war were fired—American naval forces destroyed the city of Iloilo by bombardment from the USS Petrel and the USS Baltimore. The city was captured by ground forces led by Brigadier General Marcus Miller, with no loss of American lives.[66]

Months later, after finally securing Manila from the Filipino forces, American forces moved northward, engaging in combat at the brigade and battalion level in pursuit of the fleeing insurgent forces and their commanders.[67] In response to the use of guerrilla warfare tactics by Filipino forces, beginning in September 1899,[68] American military strategy shifted to suppression of the resistance. Tactics became focused on the control of key areas with internment and segregation of the civilian population in "zones of protection" from the guerrilla population.[69] (This is considered to foreshadow the Strategic Hamlet Program that the US used decades later, during the Vietnam War). Due to disruption of war and unsanitary conditions, many of the interned civilians died from dysentery.[70]

General Otis gained notoriety for some of his actions in the Philippines. Although his superiors in Washington had directed Otis to avoid military conflict, he did very little to prevent the breakout of war. Otis refused to accept anything but unconditional surrender from the Philippine Army. He often made major military decisions without first consulting leadership in Washington. He acted aggressively in dealing with the Filipinos under the assumption that their resistance would collapse quickly. Even after this assumption proved false, he continued to insist that the insurgency had been defeated, and that the remaining casualties were caused by "isolated bands of outlaws".[71]

Otis also was active in suppressing information about American military tactics from the media. When letters describing American atrocities reached the American media, the War Department became involved and demanded that Otis investigate their authenticity. Otis had each press clipping forwarded to the original writer's commanding officer, who would convince or force the soldier to write a retraction of the original statements.[72]

Meanwhile, Otis claimed that Filipino insurgents tortured American prisoners in "fiendish fashion".[73] During the closing months of 1899, Aguinaldo attempted to counter Otis' account by suggesting that neutral parties—foreign journalists or representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross—inspect his military operations. Otis refused, but Aguinaldo managed to smuggle four reporters—two English, one Canadian, and one Japanese—into the Philippines. The correspondents returned to Manila to report that American captives were "treated more like guests than prisoners", were "fed the best that the country affords, and everything is done to gain their favor." The story said that American prisoners were offered commissions in the Filipino army and that three had accepted. The four reporters were expelled from the Philippines as soon as their stories were printed.[74][75][76]

U.S. Navy Lieutenant J.C. Gilmore, whose release was forced by American cavalry pursuing Aguinaldo into the mountains, insisted that he had received "considerable treatment" and that he was no more starved than were his captors. Otis responded to publication of two articles concerning this by ordering the "capture" of the two authors, and that they be "investigated", therefore questioning their loyalty.[77][78]

When F.A. Blake of the International Committee of the Red Cross arrived at Aguinaldo's request, Otis kept him confined to Manila. Otis' staff told him about all of the violations of international humanitarian law made by Filipino soldiers. Blake slipped away from an escort and ventured into the field. Blake never made it past American lines, but even within their territory, he saw burned-out villages and "horribly mutilated bodies, with stomachs slit open and occasionally decapitated." Blake waited to report on his findings until he returned to San Francisco, where he told one reporter that "American soldiers are determined to kill every Filipino in sight."[79][80][81]

Filipino war strategy

Estimates of the Filipino forces vary between 80,000 and 100,000, with tens of thousands of auxiliaries. Most of the forces were armed only with bolo knives, bows and arrows, spears and other primitive weapons, which were vastly inferior to the guns and other weapons of the American forces.[82]

A fairly rigid caste system existed in the Philippines during the Spanish colonial era. The goal, or end-state, sought by the First Philippine Republic was a sovereign, independent, stable nation led by an oligarchy composed of members of the educated class (known as the ilustrado class). Local chieftains, landowners, businessmen and cabezas de barangay were the principales who controlled local politics. The war was at its peak when ilustrados, principales, and peasants were unified in opposition to annexation by the United States. The peasants, who represented the majority of the fighting forces, had interests different from their ilustrado leaders and the principales of their villages. Coupled with the ethnic and geographic fragmentation, aligning the interests of people from different social castes was a daunting task. The challenge for Aguinaldo and his generals was to sustain unified Filipino public opposition; this was the revolutionaries' strategic center of gravity.[83]

The Filipino operational center of gravity was the ability to sustain its force of 100,000 irregulars in the field. The Filipino general Francisco Macabulos described the Filipinos' war aim as, "not to vanquish the U.S. Army but to inflict on them constant losses." In the early stages of the war, the Philippine Revolutionary Army employed the conventional military tactics typical of an organized armed resistance. The hope was to inflict enough American casualties to result in McKinley's defeat by William Jennings Bryan in the 1900 presidential election. They hoped that Bryan, who held strong anti-imperialist views, would withdraw the American forces from the Philippines.[84]

McKinley's election victory in 1900 was demoralizing for the insurgents, and convinced many Filipinos that the United States would not depart quickly.[84] Coupled with a series of devastating losses on the battlefield against American forces equipped with superior technology and training, Aguinaldo became convinced that he needed to change his approach. Beginning on September 14, 1899, Aguinaldo accepted the advice of General Gregorio del Pilar and authorized the use of guerrilla warfare tactics in subsequent military operations in Bulacan.[68]

Guerrilla war phase

For most of 1899, the revolutionary leadership had viewed guerrilla warfare strategically only as a tactical option of final recourse, not as a means of operation which better suited their disadvantaged situation. On November 13, 1899, Emilio Aguinaldo decreed that guerrilla war would henceforth be the strategy.[85] This made American occupation of the Philippine archipelago all the more difficult over the next few years. During the first four months of the guerrilla war, the Americans had nearly 500 casualties.[86] The Philippine Army began staging bloody ambushes and raids, such as the guerrilla victories at Paye, Catubig, Makahambus, Pulang Lupa, Balangiga and Mabitac. At first, it seemed that the Filipinos might be able to fight the Americans to a stalemate and force them to withdraw. President McKinley considered withdrawal when the guerrilla raids began.

Martial law

On December 20, 1900, General Arthur MacArthur Jr., who had succeeded Elwell Otis as U.S. Military Governor on May 5,[87] placed the Philippines under martial law, invoking U.S. Army General Order 100. He announced that guerrilla abuses would no longer be tolerated and outlined the rights which would govern the U.S. Army's treatment of guerrillas and civilians. In particular, guerrillas who wore no uniform but peasant dress and shifted from civilian to military status would be held accountable; secret committees that collected revolutionary taxes and those accepting U.S. protection in occupied towns while assisting guerrillas would be treated as "war rebels or war traitors". Filipino leaders who continued to work towards Philippine independence were deported to Guam.[88]

Decline and fall of the First Philippine Republic

The Philippine Army continued suffering defeats from the better armed United States Army during the conventional warfare phase, forcing Aguinaldo to continually change his base of operations throughout the course of the war.

On March 23, 1901, General Frederick Funston and his troops captured Aguinaldo in Palanan, Isabela, with the help of some Filipinos (called the Macabebe Scouts after their home locale[89][90]) who had joined the Americans' side. The Americans pretended to be captives of the Scouts, who were dressed in Philippine Army uniforms. Once Funston and his "captors" entered Aguinaldo's camp, they immediately fell upon the guards and quickly overwhelmed them and the weary Aguinaldo.[91]

On April 1, 1901, at the Malacañan Palace in Manila, Aguinaldo swore an oath accepting the authority of the United States over the Philippines and pledging his allegiance to the American government. On April 19, he issued a Proclamation of Formal Surrender to the United States, telling his followers to lay down their weapons and give up the fight.

"Let the stream of blood cease to flow; let there be an end to tears and desolation," Aguinaldo said. "The lesson which the war holds out and the significance of which I realized only recently, leads me to the firm conviction that the complete termination of hostilities and a lasting peace are not only desirable but also absolutely essential for the well-being of the Philippines."[92][93]

The capture of Aguinaldo dealt a severe blow to the Filipino cause, but not as much as the Americans had hoped. General Miguel Malvar took over the leadership of the Filipino government, or what remained of it.[94] He originally had taken a defensive stance against the Americans, but now launched all-out offensive against the American-held towns in the Batangas region.[18] General Vicente Lukbán in Samar, and other army officers, continued the war in their respective areas.[18]

General Bell relentlessly pursued Malvar and his men, forcing the surrender of many of the Filipino soldiers. Finally, Malvar surrendered, along with his sick wife and children and some of his officers, on April 16, 1902.[95][96] By the end of the month nearly 3,000 of Malvar's men had also surrendered. With the surrender of Malvar, the Filipino war effort began to dwindle even further.[97]

Official end to the war

The Philippine Organic Act—approved on July 1, 1902—ratified President McKinley's previous executive order which had established the Second Philippine Commission. The act also stipulated that a legislature would be established composed of a popularly elected lower house, the Philippine Assembly, and an upper house consisting of the Philippine Commission. The act also provided for extending the United States Bill of Rights to Filipinos.[99][100] On July 2, the United States Secretary of War telegraphed that since the insurrection against the United States had ended and provincial civil governments had been established throughout most of the Philippine archipelago, the office of military governor was terminated.[1] On July 4, Theodore Roosevelt, who had succeeded to the U.S. presidency after the assassination of President McKinley, proclaimed an amnesty to those who had participated in the conflict.[1][101]

On April 9, 2002, Philippine President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo proclaimed that the Philippine–American War had ended on April 16, 1902, with the surrender of General Miguel Malvar.[102] She declared the centennial anniversary of that date as a national working holiday and as a special non-working holiday in the province of Batangas and in the cities of Batangas, Lipa and Tanauan.[96]

Casualties

The total number of Filipino who died remains a matter of debate. Modern sources cite a figure of 200,000 total Filipino civilians dead, with most losses attributable to famine, and disease.[19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26] Some estimates reach 1,000,000 (one million) dead.[103][8] In 1908 Manuel Arellano Remondo, in General Geography of the Philippine Islands, wrote: "The population decreased due to the wars, in the five-year period from 1895 to 1900, since, at the start of the first insurrection, the population was estimated at 9,000,000, and at present (1908), the inhabitants of the Archipelago do not exceed 8,000,000 in number."[104] Rummel estimates that at least 16,000~20,000 Filipino soldiers and 34,000 civilians were killed,[9] with up to an additional 200,000 civilian deaths, mostly from a cholera epidemic.[105][9] Rudolph Rummel claims that 128,000 Filipinos were killed by the U.S in democide.[106] The United States Department of State states that the war "resulted in the death of over 4,200 American and over 20,000 Filipino combatants", and that "as many as 200,000 Filipino civilians died from violence, famine, and disease".[107] Bob Couttie noted in 2016 that estimates of civilian deaths range from 200,000 to 3,000,000, analyzed a number of the historical sources supporting various of those estimates, and detailed problems with the figures they reported.[108]

Atrocities

American atrocities

Throughout the war, American soldiers and other witnesses sent letters home which described some of the atrocities committed by American forces. For example, In November 1901, the Manila correspondent of the Philadelphia Ledger wrote: "The present war is no bloodless, opera bouffe engagement; our men have been relentless, have killed to exterminate men, women, children, prisoners and captives, active insurgents and suspected people from lads of ten up, the idea prevailing that the Filipino as such was little better than a dog..."[109] Reports were received from soldiers returning from the Philippines that, upon entering a village, American soldiers would ransack every house and church and rob the inhabitants of everything of value, while those who approached the battle line waving a flag of truce were fired upon.[110]

Some of the authors were critical of leaders such as General Otis and the overall conduct of the war. When some of these letters were published in newspapers, they would become national news, which would force the War Department to investigate. Two such letters included:

- A soldier from New York: "The town of Titatia was surrendered to us a few days ago, and two companies occupy the same. Last night one of our boys was found shot and his stomach cut open. Immediately orders were received from General Wheaton to burn the town and kill every native in sight; which was done to a finish. About 1,000 men, women and children were reported killed. I am probably growing hard-hearted, for I am in my glory when I can sight my gun on some dark skin and pull the trigger."[111]

- Corporal Sam Gillis: "We make everyone get into his house by seven p.m., and we only tell a man once. If he refuses we shoot him. We killed over 300 natives the first night. They tried to set the town on fire. If they fire a shot from the house we burn the house down and every house near it, and shoot the natives, so they are pretty quiet in town now."[72]

General Otis' investigation of the content of these letters consisted of sending a copy of them to the author's superior and having him force the author to write a retraction. When a soldier refused to do so, as Private Charles Brenner of the Kansas regiment did, he was court-martialed. In the case of Private Brenner, the charge was "for writing and conniving at the publication of an article which...contains willful falsehoods concerning himself and a false charge against Captain Bishop."[72] Not all such letters that discussed atrocities were intended to criticize General Otis or American actions. Many portrayed U.S. actions as the result of Filipino provocation and thus entirely justified.

Following Aguinaldo's capture by the Americans on March 23, 1901, Miguel Malvar assumed command of the Philippine revolutionary forces. Batangas and Laguna provinces were the main focus of Malvar's forces at this point in the war, and they continued to employ guerrilla warfare tactics. Vicente Lukbán remained active as Guerrilla commander in Samar.

In response to the Balangiga massacre, which wiped out a U.S. company garrisoning that Samar town, U.S. Brigadier General Jacob H. Smith launched a retaliatory march across Samar with the instructions:

I want no prisoners. I wish you to kill and burn, the more you kill and burn the better it will please me. I want all persons killed who are capable of bearing arms in actual hostilities against the United States, ...[112][113]

— Gen. Jacob H. Smith

In late 1901, Brigadier General J. Franklin Bell took command of American operations in Batangas and Laguna provinces.[114][115] In response to Malvar's guerrilla warfare tactics, Bell employed counterinsurgency tactics (described by some as a scorched earth campaign) that took a heavy toll on guerrilla fighters and civilians alike.[116] "Zones of protection" were established,[69][117] and civilians were given identification papers and forced into concentration camps (called reconcentrados) which were surrounded by free-fire zones.[117] At the Lodge Committee, in an attempt to counter the negative reception in America to General Bell's camps, Colonel Arthur Wagner, the US Army's chief public relations office, insisted that the camps were to "protect friendly natives from the insurgents, and assure them an adequate food supply" while teaching them "proper sanitary standards". Wagner's assertion was undermined by a letter from a commander of one of the camps, who described them as "suburbs of Hell".[118] Between January and April 1902, 8,350 prisoners of approximately 298,000 died, and some camps experienced mortality rates as high as 20 percent.[119]

Civilians became subject to a curfew, after which all persons found outside of camps without identification could be shot on sight. Men were rounded up for questioning, tortured, and summarily executed. Methods of torture such as the water cure were frequently employed during interrogation,[120] and entire villages were burned or otherwise destroyed.[121]

Filipino atrocities

U.S. Army General Otis alleged that Filipino insurgents tortured American prisoners in "fiendish fashion." According to Otis, many were buried alive or were placed up to their necks in ant hills. He claimed others had their genitals removed and stuffed into their mouths and were then executed by suffocation or bleeding to death. It was also reported that Spanish priests were horribly mutilated before their congregations, and natives who refused to support Emilio Aguinaldo were slaughtered by the thousands. American newspaper headlines announced the "Murder and Rapine" by the "Fiendish Filipinos." General "Fighting Joe" Wheeler insisted that it was the Filipinos who had mutilated their own dead, murdered women and children, and burned down villages, solely to discredit American soldiers.[73]

In January 1899, the New York World published a story by an anonymous writer about an American soldier, Private William Lapeer, who had allegedly been deliberately infected with leprosy. The story has no basis in fact however, and the name Lapeer itself is probably a pun.[122] Stories in other newspapers described deliberate attacks by Filipino sharpshooters upon American surgeons, chaplains, ambulances, hospitals, and wounded soldiers.[123] An incident was described in the San Francisco Call that occurred in Escalante, Negros Occidental, where several crewmen of a landing party from the CS Recorder were fired upon and later cut into pieces by Filipino insurgents, while the insurgents were displaying a flag of truce.[124]

Other events dubbed atrocities included those attributed by the Americans to General Vicente Lukban, the Filipino commander who allegedly masterminded the Balangiga massacre in Samar province, a surprise Filipino attack that killed almost fifty American soldiers.[125] Media reports stated that many of the bodies were mutilated.[126] The attack itself triggered an order for reprisals by American General Jacob Hurd Smith, who reportedly ordered his men to kill everyone over ten years old.[127] However, that order was not followed in the March across Samar expedition which was mounted following its issuance. Smith was court-martialed for this order and found guilty in 1902, which ended his career in the U.S. Army.[128]

There was testimony before the Lodge Committee that natives were given the water cure, "... in order to secure information of the murder of Private O'Herne of Company I, who had been not only killed, but roasted and otherwise tortured before death ensued."[129]

In his History of the Filipino People Teodoro Agoncillo writes that the Filipino troops could match and even exceed American brutality on some prisoners of war. Kicking, slapping, and spitting at faces were common. In some cases, ears and noses were cut off and salt applied to the wounds. In other cases, captives were buried alive. These atrocities occurred regardless of Aguinaldo's orders and circulars concerning the good treatment of prisoners.[130]

Worcester recounts two specific Filipino atrocities as follows:

A detachment, marching through Leyte, found an American who had disappeared a short time before crucified, head down. His abdominal wall had been carefully opened so that his intestines might hang down in his face. Another American prisoner, found on the same trip, had been buried in the ground with only his head projecting. His mouth had been propped open with a stick, a trail of sugar laid to it through the forest, and a handful thrown into it. Millions of ants had done the rest.[131]

Campaigns of the Philippine–American War

Political atmosphere

First Philippine Commission

Colonel Charles McC. Reeve, commander of the 13th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment, opined upon returning from the Philippines in 1899 that the war was deplorable, unjustifiable, and contrary to American principles.[63] He further stated that the war could have been prevented with conciliatory measures:

Conciliatory methods would have prevented the war. Now, we all agree to the proposition that the insurrection must be suppressed, but in the beginning a conciliatory course was not adopted. General Otis' unfortunate proclamation of January 4 rendered conciliation almost impossible.[132]

On January 20, 1899, President McKinley appointed Jacob Gould Schurman to chair a commission, with Dean C. Worcester, Charles H. Denby, Admiral Dewey, and General Otis as members, to investigate conditions in the islands and make recommendations. Fighting subsequently erupted between U.S. and Filipino forces on February 4, and when the non-military commission members arrived in the Philippines in March, they found General Otis looking upon the commission as an infringement upon his authority.[133][99]

Meetings in April with Aguinaldo's representative, Colonel Manuel Arguelles, convinced the commission that Filipinos wanted to know the specific role they would be allowed to play in the new government, and the commission requested authorization from McKinley to offer a specific plan. McKinley authorized an offer of a government consisting of "a Governor-General appointed by the President; cabinet appointed by the Governor-General; [and] a general advisory council elected by the people." McKinley also promised Filipinos "the largest measure of local self-government consistent with peace and good order," with the caveat that U.S. constitutional considerations required that the United States Congress would need to make specific rules and regulations.[134]

A session of the Revolutionary Congress convened by Aguinaldo voted unanimously to cease fighting and accept peace on the basis of McKinley's proposal. The revolutionary cabinet headed by Apolinario Mabini was replaced on May 8 by a new "peace" cabinet headed by Pedro Paterno and Felipe Buencamino. After a meeting of the Revolutionary Congress and military commanders, Aguinaldo advised the commission that he was being advised by a new cabinet "which is more moderate and concilatory", and appointed a delegation to meet with the Philippine Commission. At this point, General Antonio Luna, field commander of the revolutionary army, arrested Paterno and most of his cabinet. Confronted with this development, Aguinaldo withdrew his support from the peace cabinet, and Mabini and his original cabinet returned to power. Schurman, after proposing unsuccessfully to the Commission that they urge McKinley to revise his plan to increase Filipino participation, cabled the suggestion to the President as his own. McKinley instructed Secretary of State John Hay to cable Schurman that he wanted peace "preferably by kindness and conciliation", but the preference was accompanied by a threat to "send all the force necessary to suppress the insurrection if Filipino resistance continued." McKinley also polled the other members of the commission, receiving a response that "indecision now would be fatal" and urging "prosecution of the war until the insurgents submit."[135]

In the report that they issued to McKinley the following year, the commissioners acknowledged Filipino aspirations for independence; they declared, however, that the Philippines was not ready for it. Specific recommendations included the establishment of civilian control over Manila (Otis would have veto power over the city's government), creation of civilian government as rapidly as possible, especially in areas already declared "pacified" (the American chief executive in the islands at that time was the military governor),[133] including the establishment of a bicameral legislature, autonomous governments on the provincial and municipal levels, and a system of free public elementary schools.

On November 2, 1900, Dr. Schurman signed the following statement:

Should our power by any fatality be withdrawn, the commission believe that the government of the Philippines would speedily lapse into anarchy, which would excuse, if it did not necessitate, the intervention of other powers and the eventual division of the islands among them. Only through American occupation, therefore, is the idea of a free, self-governing, and united Philippine commonwealth at all conceivable. And the indispensable need from the Filipino point of view of maintaining American sovereignty over the archipelago is recognized by all intelligent Filipinos and even by those insurgents who desire an American protectorate. The latter, it is true, would take the revenues and leave us the responsibilities. Nevertheless, they recognize the indubitable fact that the Filipinos cannot stand alone. Thus the welfare of the Filipinos coincides with the dictates of national honour in forbidding our abandonment of the archipelago. We cannot from any point of view escape the responsibilities of government which our sovereignty entails; and the commission is strongly persuaded that the performance of our national duty will prove the greatest blessing to the peoples of the Philippine Islands. [...][136]

Second Philippine Commission

The Second Philippine Commission, appointed by President McKinley on March 16, 1900, and headed by future president William Howard Taft, was granted legislative as well as limited executive powers.[137] The commission established a civil service and a judicial system which included a Supreme Court, and a legal code was drawn up to replace obsolete Spanish ordinances. The new laws provided for popularly elected politicians to serve on municipal boards. The municipal board members were responsible for collecting taxes, maintaining municipal properties, and undertaking necessary construction projects; they also elected provincial governors.[99][100]

American opposition

Some Americans, notably William Jennings Bryan, Mark Twain, Andrew Carnegie, Ernest Crosby, and other members of the American Anti-Imperialist League, strongly objected to the annexation of the Philippines. Anti-imperialist movements claimed that the United States had become a colonial power, by replacing Spain as the colonial power in the Philippines. Other anti-imperialists opposed annexation on racist grounds. Among these was Senator Benjamin Tillman of South Carolina, who feared that annexation of the Philippines would lead to an influx of non-white immigrants into the United States. As news of atrocities committed in subduing the Philippines arrived in the United States, support for the war flagged.

Mark Twain

Mark Twain famously opposed the war by using his influence in the press. He said the war betrayed the ideals of American democracy by not allowing the Filipino people to choose their own destiny.

There is the case of the Philippines. I have tried hard, and yet I cannot for the life of me comprehend how we got into that mess. Perhaps we could not have avoided it—perhaps it was inevitable that we should come to be fighting the natives of those islands—but I cannot understand it, and have never been able to get at the bottom of the origin of our antagonism to the natives. I thought we should act as their protector—not try to get them under our heel. We were to relieve them from Spanish tyranny to enable them to set up a government of their own, and we were to stand by and see that it got a fair trial. It was not to be a government according to our ideas, but a government that represented the feeling of the majority of the Filipinos, a government according to Filipino ideas. That would have been a worthy mission for the United States. But now—why, we have got into a mess, a quagmire from which each fresh step renders the difficulty of extrication immensely greater. I'm sure I wish I could see what we were getting out of it, and all it means to us as a nation.[138]

In a diary passage removed by Twain's first biographical editor Albert Bigelow Paine, Twain refers to American troops as "our uniformed assassins" and describes their killing of "six hundred helpless and weaponless savages" in the Philippines as "a long and happy picnic with nothing to do but sit in comfort and fire the Golden Rule into those people down there and imagine letters to write home to the admiring families, and pile glory upon glory."[139]

Filipino collaboration

Some of Aguinaldo's associates supported America, even before hostilities began. Pedro Paterno, Aguinaldo's prime minister and the author of the 1897 armistice treaty with Spain, advocated the incorporation of the Philippines into the United States in 1898. Other associates sympathetic to the U.S. were Trinidad Pardo de Tavera and Benito Legarda, prominent members of Congress; Gregorio Araneta, Aguinaldo's Secretary of Justice; and Felipe Buencamino, Aguinaldo's Secretary of Foreign Affairs. Buencamino is recorded to have said in 1902: "I am an American and all the money in the Philippines, the air, the light, and the sun I consider American." Many such people subsequently held posts in the colonial government.[140]

U.S. Army Captain Matthew Arlington Batson formed the Macabebe Scouts[141] as a native guerrilla force to fight the insurgency.

Aftermath

Post-war conflicts

After military rule was terminated on July 4, 1902,[1] the Philippine Constabulary was established as an archipelago-wide police force to control brigandage and deal with the remnants of the insurgent movement. The Philippine Constabulary gradually took over the responsibility for suppressing guerrilla and bandit activities from United States Army units.[142] Remnants of the Katipunan and other resistance groups remained active fighting the United States military or Philippine Constabulary for nearly a decade after the official end of the war.[143] After the close of the war, however, Governor General Taft preferred to rely on the Philippine Constabulary and to treat the Irreconcilables as a law enforcement concern rather than a military concern requiring the involvement of the American army.

In 1902, Macario Sakay formed another government, the Republika ng Katagalugan, in Rizal Province. This republic ended in 1906 when Sakay and his top followers were arrested and executed the following year by the American authorities.[144][145]

Beginning in 1904, brigandage by organized groups became a problem in some of the outlying provinces in the Visayas. Among these groups were the Pulajanes, who were from the highlands of Samar and Leyte. The term Pulajan is derived from a native word meaning "red", as they were distinguished by the red garments they wore.[146] The Pulajanes subscribed to a blend of Roman Catholic and folk belief. For example, they believed certain amulets called agimat would render them bulletproof. These movements were all dismissed by the American government as bandits, fanatics or cattle rustlers. The last of these groups were defeated or had surrendered to the Philippine Constabulary by 1911.[146][143]

The American government had signed the Kiram-Bates Treaty with the Sultanate of Sulu at the outbreak of the war, that was supposed to prevent resistance in that part of the Philippines (which included parts of Mindanao, the Sulu Archipelago, Palawan and Sabah).[147] However, after the Filipino resistance in Luzon and the Visayas collapsed, the United States, having never intended to honor the treaty, betrayed them, canceled the treaty, and began to colonize Moro land, which provoked the Moro Rebellion.[148] Beginning with the Battle of Bayan in May 1902, the rebellion continued until the Battle of Bud Bagsak in June 1913, which marked the end of this conflict. In the Moro Crater Massacre, 994 Moros were killed.

Cultural impact

The influence of the Roman Catholic Church was reduced when the secular United States Government disestablished the Church and purchased and redistributed Church lands, one of the earliest attempts at land reform in the Philippines.[149] The land amounted to 170,917 hectares (422,350 acres), for which the Church asked $12,086,438.11 in March 1903.[150] The purchase was completed on December 22, 1903, at a sale price of $7,239,784.66.[151] The land redistribution program was stipulated in at least three laws: the Philippine Organic Act,[100] the Public Lands Act[152] and the Friar Lands Act.[153][154] Section 10 of the Public Land Act limited purchases to a maximum of 16 hectares for an individual or 1024 hectares for a corporation or like association.[152][155] Land was also offered for lease to landless farmers, at prices ranging from fifty centavos to one peso and fifty centavos per hectare per annum.[152][155] Section 28 of the Public lands Act stipulated that lease contracts may run for a maximum period of 25 years, renewable for another 25 years.[152][155]

In 1901 at least five hundred teachers (365 males and 165 females) arrived from the U.S. aboard the USS Thomas. The name Thomasite was adopted for these teachers, who firmly established education as one of America's major contributions to the Philippines. Among the assignments given were Albay, Catanduanes, Camarines Norte, Camarines Sur, Sorsogon, and Masbate, which are the present day Bicol Region, which is also the region which was heavily resistant to American rule. Twenty-seven of the original Thomasites either died of tropical diseases or were murdered by Filipino rebels during their first 20 months of residence. Despite the hardships, the Thomasites persisted, teaching and building learning institutions that prepared students for their chosen professions or trades. They opened the Philippine Normal School (now Philippine Normal University) and the Philippine School of Arts and Trades (PSAT) in 1901 and reopened the Philippine Nautical School, established in 1839 by the Board of Commerce of Manila under Spain. By the end of 1904, primary courses were mostly taught by Filipinos under American supervision.[156]

In The Media

The 2010 film Amigo, the 2015 film Heneral Luna and it's 2018 sequel, Goyo: The Boy General were based on the war.

Philippine independence and sovereignty (1946)

.jpg)

On January 20, 1899, President McKinley appointed the First Philippine Commission (the Schurman Commission), a five-person group headed by Dr. Jacob Schurman, president of Cornell University, to investigate conditions in the islands and make recommendations. In the report that they issued to the president the following year, the commissioners acknowledged Filipino aspirations for independence; they declared, however, that the Philippines was not ready for it. Specific recommendations included the establishment of civilian government as rapidly as possible (the American chief executive in the islands at that time was the military governor), including establishment of a bicameral legislature, autonomous governments on the provincial and municipal levels, and a new system of free public elementary schools.[142]

From the very beginning, United States presidents and their representatives in the islands defined their colonial mission as tutelage: preparing the Philippines for eventual independence.[157] Except for a small group of "retentionists", the issue was not whether the Philippines would be granted self-rule, but when and under what conditions.[157] Thus political development in the islands was rapid and particularly impressive in light of the complete lack of representative institutions under the Spanish. The Philippine Organic Act of July 1902 stipulated that, with the achievement of peace, a legislature would be established composed of a lower house, the Philippine Assembly, which would be popularly elected, and an upper house consisting of the Philippine Commission, which was to be appointed by the president of the United States.[142]

The Jones Act, passed by the U.S. Congress in 1916 to serve as the new organic law in the Philippines, promised eventual independence and instituted an elected Philippine senate. The Tydings–McDuffie Act (officially the Philippine Independence Act; Public Law 73-127) approved on March 24, 1934, provided for self-government of the Philippines and for Filipino independence (from the United States) after a period of ten years. World War II intervened, bringing the Japanese occupation between 1941 and 1945. In 1946, the Treaty of Manila (1946) between the governments of the U.S. and the Republic of the Philippines provided for the recognition of the independence of the Republic of the Philippines and the relinquishment of American sovereignty over the Philippine Islands.

See also

- Battle of Cagayan de Misamis

- Campaigns of the Philippine–American War

- Foreign interventions by the United States

- History of the Philippines (1898–1946)

- List of Philippine–American War Medal of Honor recipients

- Philippines–United States relations

- El Presidente (film)

- Timeline of the Philippine–American War

- United States involvement in regime change

Notes

- The Mexican dollar at the time was worth about 50 US cents,[34] equivalent to about $15.5 today. The peso fuerte and the Mexican dollar were interchangeable at par.

- Worcester 1914, p. 293.

- "Diplomatic relations between the Philippines and Japan". Diplomatic relations. Manila: Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. 2016. Archived from the original on August 27, 2015. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

On February 4, 1899, the Philippine-American War broke out. A handful of Japanese shishi, or ultranationalists, fought alongside President Aguinaldo's army. They landed in Manila, led by Captain Hara Tei and joined Aguinaldo's forces in Bataan.

- "Historian Paul Kramer revisits the Philippine–American War". The JHU Gazette. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. 35 (29). April 10, 2006. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- Deady 2005, p. 62 (p.10 of the pdf)

- Deady 2005, p. 55 (p.3 of the pdf)

- Karnow 1989, p. 194.

- Hack & Rettig 2006, p. 172.

- Burdeos 2008, p. 14

- Ramsey 2007, p. 103.

- Smallman-Raynor, Matthew; Cliff, Andrew D. (1998). "The Philippines insurrection and the 1902–4 cholera epidemic: Part I—Epidemiological diffusion processes in war". Journal of Historical Geography. 24 (1): 69–89. doi:10.1006/jhge.1997.0077.

- "Philippines Background Note". U.S. Bilateral Relations Fact Sheets: Background Notes. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of State. 2004. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- Battjes 2011, p. 74.

- Silbey 2008, p. 15.

- "The Philippine-American War, 1899–1902". Office of the Historian, U.S. Department of State. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- Randolph 2009.

- Kalaw 1927, pp. 199–200.

- Paterno, Pedro Alejandro (June 2, 1899). "Pedro Paterno's Proclamation of War". The Philippine-American War Documents. San Pablo City, Philippines: MSC Institute of Technology, Inc. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- Agoncillo 1990, pp. 247–297.

- Clodfelter, Michael, Warfare and Armed Conflict: A Statistical Reference to Casualty and Other Figures, 1618–1991

- Leon Wolff, Little Brown Brother (1961) p.360

- Benjamin A. Valentino, Final solutions: mass killing and genocide in the twentieth century (2005) p.27

- FAS 2000: Federation of American Scientists, The World at War (2000)

- Philip Sheldon Foner, The Spanish-Cuban-American War and the Birth of American Imperialism (1972) p.626

- George C. Herring, From colony to superpower: U.S. foreign relations since 1776 (2008) p.329

- Graff, American Imperialism and the Philippine Insurrection (1969)

- Irving Werstein, 1898: The Spanish American War: told with pictures (1966) p.124

- Tucker, Spencer (2009). The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 478. ISBN 9781851099511.

- "The Road to Women's Suffrage in the Philippines". Bayanihan News. August 8, 2014.

- United States Congress (August 29, 1916). "Philippine Autonomy Act". thecorpusjuris.com.

- In the "Instructions of the President to the Philippine Commission Archived February 27, 2009, at the Wayback Machine" dated April 7, 1900, President William McKinley reiterated the intentions of the United States Government to establish and organize governments, essentially popular in their form, in the municipal and provincial administrative divisions of the Philippine Islands. However, there was no official mention of any declaration of Philippine Independence.

- Agoncillo 1990, pp. 180–181.

- "Emilio Aguinaldo". Presidential Museam and Library. Malacañan Palace.

- "Proclamation No. 1231, s. 2016". February 29, 2016.

General Emilio Aguinaldo, the first President of the Republic of the Philippines

- Halstead 1898, p. 126.

- Halstead 1898, p. 177.

- Aguinaldo 1899, p. 4.

- Constantino 1975, p. 192.

- Miller 1982, p. 35.

- Ocampo, Ambeth R. (January 7, 2005). "The first Philippine novel". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Manila.

- Brands 1992, p. 46.

- Steinberg, David Joel (1972). "An Ambiguous Legacy: Years at War in the Philippines". Pacific Affairs. 45 (2): 165–190. doi:10.2307/2755549. JSTOR 2755549.

- Aguinaldo 1899, p. 5.

- Aguinaldo 1899, pp. 12–13.

- Aguinaldo 1899, pp. 15–16.

- "Treaty of Peace Between the United States and Spain; December 10, 1898". The Avalon Project. New Haven, Connecticut: Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School. 2008. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- Jaycox 2005, p. 130.

- Agoncillo 1990, pp. 199–212.

- Aguinaldo 1899, pp. 10–12.

- Aguinaldo 1899, p. 10.

- "Spencer-Pratt and Aguinaldo" (PDF). The New York Times. New York City. August 26, 1899.

- Agoncillo 1990, pp. 213–214.

- Agoncillo 1990, p. 196.

- "Introduction". The World of 1898: The Spanish–American War. Washington, D.C.: Hispanic Division, United States Library of Congress. 2011. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- Seekins, Donald M. (1991). "Outbreak of War, 1898". In Dolan, Ronald E. (ed.). Philippines: A Country Study. Washington, D.C.: United States Library of Congress.

- "Why Did America Cross the Pacific? Reconstructing the U.S. Decision to Take the Philippines, 1898-99". Texas National Security Review. November 25, 2017. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- The text of the amended version published by General Otis is quoted in its entirety in José Roca de Togores y Saravia; Remigio Garcia; National Historical Institute (Philippines) (2003). Blockade and siege of Manila. National Historical Institute. pp. 148–150. ISBN 978-971-538-167-3.; See also s:Letter from E.S. Otis to the inhabitants of the Philippine Islands, January 4, 1899.

- Agoncillo 1990, pp. 214–215.

- Agoncillo 1990, p. 215.

- Agoncillo 1990, p. 216.

- Chaput, Donald (1980). "Private William W Grayson's war in the Philippines, 1899" (PDF). Nebraska History. 61: 355–66.

- "National Historical Institute Board Resolution No. 7, s. 2003". Manila: National Historical Commission of the Philippines. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- Palafox, Quennie Ann J. (September 6, 2012). "Betrayal of Trust – The San Juan Del Monte Bridge Incident". Manila: National Historic Commission of the Philippines. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- "The week". The Nation. Vol. 68 no. 1766. May 4, 1899. p. 323.

- Agoncillo 1990, p. 217.

- Miller 1982, p. 2.

- Special Dispatch (February 14, 1899). "Iloilo is taken and no American loses his life". San Francisco Call. 85 (76). San Francisco. p. 1.

- Lone 2007, p. 56.

- Worcester 1914, p. 285.

- Worcester 1914, pp. 290–293.

- Lone 2007, p. 58.

- Miller 1982, pp. 63–66.

- Miller 1982, p. 89.

- Miller 1982, pp. 92–93.

- Miller 1982, p. 93.

- Public Opinion volume 27 (1899), p. 291

- San Francisco Call February 23, March 30, 31, 1899.

- Miller 1982, pp. 93–94.

- Literary Digest Volume 18 (1899), p. 499

- Miller 1982, p. 94.

- Boston Globe June 27, 1900

- Literary Digest Volume 20 (1900), p. 25;

- Deady 2005, p. 55,67 (p.3,14 of the pdf)

- Deady 2005, p. 57 (p.5 of the pdf)

- Deady 2005, p. 58 (p.6 of the pdf)

- Linn 2000, pp. 186–187, 362 (notes 5 and 6).

- Sexton 1939, p. 237.

- Pershing, John J. (2013). My Life Before the World War, 1860—1917: A Memoir. University Press of Kentucky. p. 547. ISBN 0-8131-4199-0.

- Linn, Brian McAllister (2000). The U.S. Army and Counterinsurgency in the Philippine War, 1899–1902. UNC Press Books. pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-0-8078-4948-4.

- Birtle 1998, pp. 116–118.

- Keenan 2001, pp. 211–212.

- Linn 2000, p. 175.

- Aguinaldo y Famy, Don Emilio (April 19, 1901). "Aguinaldo's Proclamation of Formal Surrender to the United States". The Philippine-American War Documents. Pasig City, Philippines: Kabayan Central Net Works Inc. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- Brands 1992, p. 59.

- Cruz, Maricel V. "Lawmaker: History wrong on Gen. Malvar." Manila Times, January 2, 2008 (archived on December 11, 2008)

- Tucker 2009, p. 217.

- Macapagal Arroyo, Gloria (April 9, 2002). "Proclamation No. 173. s. 2002". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Manila. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- Tucker 2009, pp. 477–478.

- Bruno, Thomas A (2011). "The Violent End of Insurgency on Samar, 1901–1902" (PDF). Army History. 79 (Spring): 30–46.

- "Philippines: United States Rule". Washington, D.C.: United States Library of Congress. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- "The Philippine Bill (enacted July 1, 1902)". ChanRobles Virtual Law Library: Philippine Laws, Statutes & Codes. Manila: ChanRobles & Associates Law Firm. 2016. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- "General amnesty for the Filipinos; proclamation issued by the President" (PDF). The New York Times. New York City. July 4, 1902.

- "Speech of President Arroyo during the Commemoration of the Centennial Celebration of the end of the Philippine-American War April 16, 2002". Official Gazette. Government of the Philippines.

- Tucker, Spencer (2009). The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 478. ISBN 9781851099511.

- Boot 2014, p. 125.

- Rummel, Rudolph J. (1998). Statistics of Democide: Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1900. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 201. ISBN 978-3-8258-4010-5.

- "Statistics of American Genocide and Mass Murder". www.hawaii.edu.

- The Philippine-American War, 1899–1902 Archived October 19, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, U.S. State Department, Office of the Historian.

- Bob Couttie, Philippine Genocide – The Numbers Don't Add Up.

- Zinn 2003, p. 230.

- Coulter, Clinton R. (August 1, 1899). "Our policy in the Philippines". San Francisco Call. 86 (62). San Francisco. p. 6.

- Miller 1982, p. 88.

- "President Retires Gen. Jacob H. Smith" (PDF). The New York Times. July 17, 1902. Retrieved March 30, 2008.

- Melshen, Paul. "Littleton Waller Tazewell Waller". Archived from the original on April 21, 2008. Retrieved March 30, 2008.

- Schirmer, Daniel B.; Shalom, Stephen Rosskamm (1987). The Philippines Reader: A History of Colonialism, Neocolonialism, Dictatorship, and Resistance. South End Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-89608-275-5.

- Linn 2000, p. 152.

- Francisco et al. 1999, p. 18.

- Storey & Codman 1902, pp. 32, 64, 77–79, 89–95.

- Stuart Creighton Miller, Benevolent Assimilation: The American Conquest of the Philippines, 1899–1903, 1982 p.244.

- McLachlan 2012, p. 565.

- Storey & Codman 1902, pp. 44, 48–49, 61–62, 65, 67.

- Storey & Codman 1902, pp. 10, 38, 64, 95.

- Brody 2010, pp. 69–71.

- Bennett, James Gordon (February 21, 1899). "Aguinaldo's dusky demons in arms making war on those who aid the wounded". San Francisco Call. 85 (83). San Francisco. p. 1.

- Special Dispatch (May 29, 1899). "Treachery of natives of Negros: display a flag of truce and then fire upon landing party of Americans". San Francisco Call. 85 (180). San Francisco. p. 1.

- Oswald, Mark (2001). The "howling wilderness" courts-martial of 1902. Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania: United States Army War College.

- Boot 2014, p. 204.

- Simmons 2003, p. 78.

- "Bob Couttie Archived October 17, 2015, at the Wayback Machine"

- "The water cure described: discharged soldier tells Senate committee how and why the torture was inflicted" (PDF). The New York Times. New York City. May 4, 1902.

- Agoncillo 1990, pp. 227–231.

- Worcester 1914, p. 384.

- "There was no necessity for war in the Philippine islands". San Francisco Call. 86 (106). San Francisco. September 14, 1899. p. 1.

- Miller 1982, p. 132.

- Golay 2004, pp. 49–50.

- Golay 2004, p. 50.

- Schurman et al. 1900, p. 183.

- Kalaw 1927, pp. 452–459 (Appendix F).

- Twain, Mark (October 6, 1900). "Mark Twain, the greatest American humorist, returning home". New York World. New York City.

- Rohter, Larry (July 9, 2010). "Dead for a century, Twain says what he meant". The New York Times. New York City.

- Buencamino, Felipe (1902). Statement before the Committee on Insular Affairs on conditions in the Philippine islands. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Publishing Office. p. 64.

- "NEW FILIPINO HORSE.; Four Troops of Macabebes to be Formed with Americans as Officers" Archived March 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, New York Times, July 17, 1900.

- Dolan 1991.

- "Otoy, Filipino bandit, slain by Constabulary". San Francisco Call. 110 (134). San Francisco. October 12, 1911. p. 5.

- Ileto 1997, pp. 193–197.

- Froles, Paul. "Macario Sakay: Tulisán or Patriot?". Philippine History Group of Los Angeles. Archived from the original on June 9, 2007.

- Worcester 1914, pp. 392–395.

- https://claimsabah.wordpress.com/2011/08/31/the-kiram-bates-treaty/

- Welman, Frans (2012). Face of the New Peoples Army of the Philippines: Volume Two Samar. Booksmango. p. 134. ISBN 978-616-222-163-7.

- Seekins, Donald M. (1991). "The First Phase of United States Rule, 1898–1935". In Dolan, Ronald E. (ed.). Philippines: A Country Study (4th ed.). Washington, D.C.: United States Library of Congress.

- Escalante 2007, pp. 223–224.

- Escalante 2007, p. 226.

- "Act No. 926 (enacted October 7, 1903)". ChanRobles Virtual Law Library: Philippine Laws, Statutes & Codes. Manila: ChanRobles & Associates Law Firm. 2016. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- "Act No. 1120 (enacted April 26, 1904)". ChanRobles Virtual Law Library: Philippine Laws, Statutes & Codes. Manila: ChanRobles & Associates Law Firm. 2016. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- Escalante 2007, p. 218.

- Escalante 2007, p. 219.

- "Thomasites: An army like no other". Government of the Philippines. October 12, 2003. Archived from the original on April 29, 2008. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- Escalante 2007, pp. 48–54.

References

- Agoncillo, Teodoro A. (1990) [1960]. History of the Filipino People (Eighth ed.). Quezon City: Garotech Publishing. ISBN 978-9718711064.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Agoncillo, Teodoro A. (1997). Malolos: The crisis of the republic. Philippine studies reprint series. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press. ISBN 978-9715420969.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Aguinaldo, Don Emilio (1899). True version of the Philippine revolution. Tarlac, Philippines: self-published.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Anderson, Gerald R. (2009). Subic Bay from Magellan to Pinatubo: The History of the U.S. Naval Station, Subic Bay. Gerald Anderson. ISBN 978-1-4414-4452-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Arnold, James R. (2011). The Moro War: How America Battled a Muslim Insurgency in the Philippine Jungle, 1902-1913. New York City: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60819-365-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Battjes, Mark E. (2011). Protecting, Isolating, and Controlling Behavior: Population and Resource Control Measures in Counterinsurgency Campaigns (PDF). United States Army Combined Arms Center, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-9837226-6-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 15, 2018. Retrieved December 11, 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bayor, Ronald H. (2004). The Columbia Documentary History of Race and Ethnicity in America. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11994-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Birtle, Andrew J. (1998). U.S. Army counterinsurgency and contingency operations doctrine 1860–1941. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Publishing Office. ISBN 978-0-16-061324-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Blitz, Amy (2000). The Contested State: American Foreign Policy and Regime Change in the Philippines. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-8476-9935-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Boot, Max (2014). The Savage Wars of Peace: Small Wars And The Rise Of American Power (Revised ed.). New York City: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-03866-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brands, Henry William (1992). Bound to Empire: The United States and the Philippines. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507104-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brody, David (2010). Visualizing American Empire: Orientalism and Imperialism in the Philippines. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226075341.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brooks, Van Wyck (1920). Ordeal of Mark Twain. E.P. Dutton & Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burdeos, Ray L. (2008). Filipinos in the U.S. Navy & Coast Guard During the Vietnam War. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4343-6141-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chambers, John W.; Anderson, Fred (1999). The Oxford Companion to American Military History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507198-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chapman, William (1988). Inside the Philippine revolution. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-85043-114-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coker, Kathy R. (1989). The Signal Corps and the U.S. Army Regimental System. U.S. Army Signal Center.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coker, Kathy R.; Stokes, Carol E. (1991). A Concise History of the U.S. Army Signal Corps. U.S. Army Signal Center.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Constantino, Renato (1975). The Philippines: A Past Revisited. Renato Constantino. ISBN 978-971-8958-00-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (note: page number info in short footnotes citing this work may be incorrect—work is underway to correct this)

- Halstead, Murat (1898). The Story of the Philippines and Our New Possessions, Including the Ladrones, Hawaii, Cuba and Porto Rico. Chicago: Our Possessions Publishing Company.

- Deady, Timothy K. (2005). "Lessons from a Successful Counterinsurgency: The Philippines, 1899–1902" (PDF). Parameters. Carlisle, Pennsylvania: United States Army War College. 35 (1): 53–68. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 10, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dolan, Ronald E., ed. (1991). "United States Rule". Philippines: A Country Study. Washington, D.C.: United States Library of Congress.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Escalante, Rene R. (2007). The Bearer of Pax Americana: The Philippine Career of William H. Taft 1900–1903. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. ISBN 978-971-10-1166-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Feuer, A. B. (2002). America at War: The Philippines, 1898–1913. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-275-96821-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Francisco, Luzviminda; Jenkins, Shirley; Taruc, Luis; Constantino, Renato; et al. (1999). Schirmer, Daniel B.; Shalom, Stephen Rosskamm (eds.). The Philippines Reader: A History of Colonialism, Neocolonialism, Dictatorship, and Resistance. Brooklyn, New York: South End Press. ISBN 978-0896082755.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gates, John M. (1973). Schoolbooks and Krags: The United States Army in the Philippines, 1898–1902. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8371-5818-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gates, John M. (1983). War-Related Deaths in the Philippines, 1898–1902. Pacific Historical Review. 53.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gates, John M. (2002). The U.S. Army and Irregular Warfare (PDF). Wooster, Ohio: The College of Wooster.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Giddings, Howard A. (1900). Exploits of the Signal Corps in the War With Spain. Hudson-Kimberly Publishing Co. pp. 15–16, 83.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Golay, Frank Hindman (2004). Face of Empire: United States-Philippine Relations, 1898–1946. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 978-1881261179.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Guevara, Sulpico, ed. (1972). The laws of the first Philippine Republic (the laws of Malolos) 1898–1899. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Library.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hack, Karl; Rettig, Tobias (2006). Colonial Armies in Southeast Asia (Routledge Studies in the Modern History of Asia). Abingdon-on-Thames, United Kingdom: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-33413-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Halstead, Murat (1898). The Story of the Philippines and Our New Possessions, Including the Ladrones, Hawaii, Cuba and Porto Rico. Chicago: Our Possessions Publishing Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hamilton, Richard F. (2007). President McKinley and America's "New Empire". Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7658-0383-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ileto, Reynaldo Clemeña (1997). Pasyon and revolution: popular movements in the Philippines, 1840–1910. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 978-9715502320.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jaycox, Faith (2005). The Progressive Era: Eyewitness History (Eyewitness History Series). New York City: Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8160-5159-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Joaquin, Nicomedes (1977). A Question of Heroes. ISBN 971-27-1545-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kalaw, Maximo Manguiat (1927). The development of Philippine politics (1872-1920). Manila: Oriental Commercial Company, Inc.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Karnow, Stanley (1989). In Our Image: America's Empire in the Philippines. New York City: Random House. ISBN 978-030777543-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Keenan, Jerry (2001). Encyclopedia of the Spanish–American & Philippine–American wars. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-093-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McLachlan, Grant (2012). Sparrow: A Chronicle of Defiance: The story of The Sparrows –Battle of Britain gunners who defended Timor as part of Sparrow Force during World War II. Klaut. ISBN 978-0-473-22623-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kumar, Amitava (1999). Poetics/Politics: Radical Aesthetics for the Classroom. Palgrave. ISBN 0-312-21866-4.

- Lacsamana, Leodivico Cruz (1990). Philippine History and Government (2nd ed.). Phoenix Publishing House, Inc. ISBN 971-06-1894-6.

- Linn, Brian McAllister (2000). The U.S. Army and counterinsurgency in the Philippine war, 1899–1902. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0807849484.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lone, Stewart (2007). Daily Lives of Civilians in Wartime Asia: From the Taiping Rebellion to the Vietnam War. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0313336843.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- May, Glenn Anthony (1991). Battle for Batangas: A Philippine Province at War. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-04850-5.

- Meyer, Carlton (2019). The American Invasion of the Philippines. California: G2mil.

- Miller, Stuart Creighton (1982). Benevolent assimilation: the American conquest of the Philippines, 1899—1903. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-03081-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Minahan, James (2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: L-R. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32111-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Paine, Albert Bigelow (1912). Mark Twain: A Biography: The Personal and Literary Life of Samuel Langhorne Clemens. Harper & Brothers. Archived from the original on November 17, 2013.

- Painter, Nell Irvin (1989). Standing at Armageddon: The United States, 1877–1919. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-30588-0.

- "Race-Making and Colonial Violence in the U.S. Empire: The Philippine–American War as Race War," Diplomatic History, Vol. 30, No. 2 (April 2006), 169–210. (version at Japanfocus.org).

- Ramsey, Robert D. III (2007). Savage Wars of Peace: Case Studies of Pacification in the Philippines, 1900–1902 (PDF). United States Army Combined Arms Center, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-16-078950-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 16, 2019. Retrieved December 11, 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Randolph, Carman Fitz (2009). "Chapter I, The Annexation of the Philippines". The Law and Policy of Annexation. Charleston, South Carolina: BiblioBazaar, LLC. ISBN 978-1-103-32481-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)