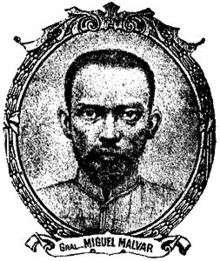

Miguel Malvar

Miguel Malvar y Carpio (September 27, 1865 – October 13, 1911) was a Filipino general who served during the Philippine Revolution and, subsequently, during the Philippine–American War. He assumed command of the Philippine revolutionary forces during the latter, following the capture of Emilio Aguinaldo by the Americans in 1901. According to some historians, he could have been listed as one of the presidents of the Philippines but is currently not recognized as such by the Philippine government.

Miguel Carpio Malvar | |

|---|---|

| President of the First Philippine Republic (Unofficial) | |

| In office April 1, 1901 – April 16, 1902 | |

| Preceded by | Emilio Aguinaldo |

| Succeeded by | Macario Sakay (as President of the Tagalog Republic) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Miguel Malvar y Carpio September 27, 1865 Santo Tomas, Batangas, Captaincy General of the Philippines |

| Died | October 13, 1911 (aged 46) Manila, Philippine Islands |

| Resting place | Santo Tomas, Batangas |

| Political party | Katipunan |

| Spouse(s) | Paula Maloles |

| Children | 11[1] |

| Profession | Revolutionary |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Philippine Revolutionary Army |

| Years of service | 1896–1902 |

| Rank | General |

| Commands | Batangas Brigade (also known as the Malvar Brigade) |

| Battles/wars | Philippine Revolution Philippine–American War |

Early life

Malvar was born on September 27, 1865 in San Miguel, a barrio in Santo Tomas, Batangas, to Máximo Malvar (locally known as Capitan Imoy) and Tiburcia Carpio (locally known as Capitana Tibo). Malvar's family was well known in town not only for their wealth but for their generosity and diligence as well.[2]

For his education, Malvar attended the town school in Santo Tomas. He later attended a private school run by Father Valerio Malabanan in Tanauan, Batangas, which was considered a famous educational institution in Batangas at the time. Here, Malvar had fellow revolutionary Apolinario Mabini as his classmate. He then transferred to another school in Bauan, Batangas. He decided not to pursue higher education in Manila and preferred to settle down as a farmer instead. Instead, he helped his more studious younger brother, Potenciano, study medicine in Spain. Malvar was later elected as capitan municipal of his hometown.[2]

In 1891, Malvar married Paula Maloles, the beautiful daughter of the capitan municipal of Santo Tomas, Don Ambrocio Maloles. Don Ambrocio was Malvar's successor as capitan municipal.[2] Ulay, as she was locally known, bore Malvar thirteen children, but only eleven of them survived: Bernabe, Aurelia, Marciano, Maximo, Crispina, Mariquita, Luz Constancia, Miguel (Junior), Pablo, Paula, and Isabel. Malvar had the habit of bringing his family with him as he went to battle during the Philippine Revolution and the Philippine–American War.[2]

Connections with Rizal

Malvar and his family had a friendship with José Rizal and his family. Doctor Rizal mended the harelip of Malvar's wife, and Saturnina Rizal lent Malvar 1,000 pesos as an initial capital to start a business.[2] Saturnina's husband, Manuel, was a relative of Malvar's, and Soledad Rizal Quintero's daughter, Amelia married Malvar's eldest son, Bernabe. Also, Joseng batute was Malvar's fellow revolutionary.[2]

Philippine Revolution

Like Macario Sakay, his subsequent successor as president, Malvar was an original Katipunero as they both joined the Katipunan before the Philippine Revolution. When the Revolution began in August 1896, Marval emerged from leading a 70-man army to becoming the military commander of Batangas. As military commander, he coordinated offensives with General Emilio Aguinaldo, leader of the revolutionaries in Cavite, and General Paciano Rizal, leader of the revolutionaries in Laguna.[2] On February 17, 1897, Marval fought alongside General Edilberto Evangelista, Malvar's senior officer at the time, at the Battle of Zapote Bridge, where the senior died in battle. Succeeding Evangelista's generalship, Malvar had set up his own headquarters at Indang, Cavite, where he stayed until the Tejeros Convention.[2]

After the Tejeros Convention, in which Aguinaldo won as president, Malvar opted to side with the Katipunan's Supremo, Andrés Bonifacio. In response to Malvar's support, Bonifacio gave them assistance in fighting their battles. Seeing the mutual relations between Malvar and Bonifacio, Aguinaldo decided to use his newly acquired position to put Batangas, as well as Malvar, under his jurisdiction.[2] Malvar was also threatened with punishment if he did not break ties with Bonifacio, but this threat was never implemented. Bonifacio and his brother Procopio were found guilty, despite insufficient evidence, and they were recommended to be executed. Aguinaldo 'issued a commutation of sentence' to deportation or exile on May 8, 1897, but Pío del Pilar and Mariano Noriel, both former supporters of Bonifacio, persuaded Aguinaldo to withdraw the order for the sake of preserving unity. In this they were seconded by Mamerto Natividád and other bona fide supporters of Aguinaldo.[3] The Bonifacio brothers were murdered on 10 May 1897 in the mountains of Maragondon.[3][4]

After Bonifacio was bumped off, the Spanish offensive resumed, now under Governor-General Fernando Primo de Rivera, and forced Aguinaldo out of Cavite. Aguinaldo slipped through the Spanish cordon and, with 500 picked men, proceeded to Biak-na-Bató,[5] a wilderness area at the tri-boundaries of the towns of San Miguel, San Ildefonso and Doña Remedios in Bulacan.[6] When news of Aguinaldo's arrival there reached the towns of central Luzon, men from the Ilocos provinces, Nueva Ecija, Pangasinan, Tarlac, and Zambales, renewed their armed resistance against the Spanish.[5]

On November 1, 1897, the provisional constitution for the Biak-na-Bato Republic was signed.[7] By the end of 1897, Governor-General Primo de Rivera accepted the impossibility of quelling the revolution by force of arms. In a statement to the Cortes Generales, he said, "I can take Biak-na-Bato, any military man can take it, but I can not answer that I could crush the rebellion." Desiring to make peace with Aguinaldo, he sent emissaries to Aguinaldo seeking a peaceful settlement. Nothing was accomplished until Pedro A. Paterno, a distinguished lawyer from Manila perhaps wanting a Spanish nobility title,[8] volunteered to act as negotiator. On August 9, 1897, Paterno proposed a peace based on reforms and amnesty to Aguinaldo. In succeeding months, practicing shuttle diplomacy, Paterno traveled back and forth between Manila and Biak-na-Bato carrying proposals and counterproposals. Paterno's efforts led to a peace agreement called the Pact of Biak-na-Bato. This consisted of three documents, the first two being signed on December 14, 1897, and the third being signed on December 15; effectively ending the Republic of Biak-na-Bato.[9]

Malvar, along with other generals like Mariano Trías, Paciano Rizal, Manuel Tinio and Artemio Ricarte, was opposed to the pact, believing it was a ruse of the Spanish to get rid of the Revolution easily, and therefore resumed military offensives. Aguinaldo, seeing the stiff resistance of Malvar and his sympathizers, issued a circular ordering the revolutionary generals to stop fighting. On January 6, 1898, Malvar ceased his offensives.[2]

Philippine–American War

On May 19, 1898, Aguinaldo, aboard the American revenue cutter McCulloch, returned to the Philippines with 13 of his military staff. After four days, the first delivery of arms from Hong Kong arrived. It amounted to 2,000 rifles and 200,000 rounds of ammunition.[2] With Aguinaldo's return, the Filipinos, numbering around 12,000, who enlisted under the Spanish flag in the war against America defected to Aguinaldo's banner. By June, Philippine independence was declared in Kawit, Cavite and Manila found herself surrounded by Aguinaldo's troops. But on August 13, 1898, it was the Americans who captured Manila.[2]

On February 4, 1899, hostilities began between Americans and Filipinos. On February 7, Malvar was appointed second-in-command of General Trías, who was the overall commander of the Filipino forces in southern Luzon.[2] On February 23, General Antonio Luna needed Malvar and his unit to take part in a Filipino counterattack that was planned to regain ground lost earlier by Filipinos and capture Manila. However, the Filipino offensive collapsed mainly due to the insubordination of the Kawit Battalion.[10] During the following months, Malvar harassed American troops south of Manila as he and his 3,000-man brigade conducted offensives in Muntinlupa. By July 1899, the Americans under General Robert Hall captured Calamba, Laguna. With ten companies (around 2,000 men) of American troops in the town, Malvar unsuccessfully besieged Calamba from August to December 1899.[2]

On November 13, 1899, Aguinaldo disbanded the Filipino regular army, forming them into guerrilla units at Bayambang, Pangasinan and afterwards conducted his escape journey to Palanan, Isabela, which he reached by September 6, 1900.[11] This change in tactics was not as successful as it had been against the Spaniards, and Aguinaldo was captured on March 23, 1901, by General Frederick Funston with help from some Macabebe scouts. General Trías, Aguinaldo's chosen successor as president and Commander-In-Chief of the Filipino forces, had already surrendered on March 15, 1901. Therefore, as designated in Aguinaldo's decreed line of succession, Malvar became President of the Philippine Republic. The Hong Kong Junta affirmed Malvar's authority in succeeding Aguinaldo.[2] As he took over the affairs of the Republic, Malvar reorganized Filipino forces in southern Luzon and renamed the combined armed forces as "Army of Liberation", which possessed around 10,000 rifles at the time. He also reorganized the regional departments of the Republic, which included the Marianas as a separate province.[2]

Beginning January 1902, American General J. Franklin Bell took command of operations in Batangas and practiced scorched earth tactics that took a heavy toll on both guerrilla fighters and civilians alike. Malvar escaped American patrols by putting on disguises. So, as early as August 1901, the Americans released an exact description of Malvar's physical features.[2] According to the description given, Malvar was of dark complexion and stood around 5 feet 3 inches. He weighed about 145 pounds and wore a 5 or 6 size of shoes.[2] He surrendered to Bell on April 13, 1902 in Rosario, Batangas, mainly due to desertion of his top officers and to put an end to the sufferings of his countrymen.[2]

After the war, he refused any position offered to him in the American colonial government. He died in Manila on October 13, 1911, due to liver failure. He was buried in his hometown, Santo Tomas, Batangas, on October 15.[2]

Controversies on his attribution as President

On September 18, 2007, Rodolfo Valencia, Representative of Oriental Mindoro filed House Bill 2594, that declared Malvar as the second Philippine President, alleging that it is incorrect to consider Manuel L. Quezon as the Second President of the Philippine Republic serving after Emilio Aguinaldo: "General Malvar took over the revolutionary government after General Emilio Aguinaldo, first President of the Republic, was captured on March 23, 1901, and [was] exiled in Hong Kong by the American colonial government—since he was next in command."[12] In October 2011, Vice President Jejomar Binay sought the help of historians in proclaiming revolutionary General Miguel Malvar as the rightful second President of the Philippines.[13]

Commemoration

- The Miguel Malvar class corvette, named after Malvar, is a ship class of patrol corvettes of the Philippine Navy, and are currently its oldest class of corvettes.

- Extra Mile Productions conducted the General Miguel Malvar Essay Writing Contest in commemoration of the 100th Death Anniversary of General Miguel Malvar.[14]

- Malvar, Batangas, a second class municipality in the Philippines, was named after him.

- In 2015, the National Historical Commission of the Philippines will open a museum in Santo Tomas to celebrate the 150th anniversary of Malvar's birthday on September 27.[15]

- In 2015, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) released the 10-peso commemorative coin in honor of Malvar's 150th birth anniversary.[16]

- Malvar monument in Malvar, Batangas

.jpg) BRP Miguel Malvar (PS-19), the lead ship of the Miguel Malvar class corvette

BRP Miguel Malvar (PS-19), the lead ship of the Miguel Malvar class corvette Commemorative ₱10 coin released in 2015 by the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas in commemoration of Malvar's 150th birth anniversary. The obverse is shown on the left, while the reverse is on the right.

Commemorative ₱10 coin released in 2015 by the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas in commemoration of Malvar's 150th birth anniversary. The obverse is shown on the left, while the reverse is on the right.

See also

- List of Unofficial Presidents of the Philippines

References

- Chua, Michael Charleston. "A historian's perspective: Gen. Malvar could have been the Pacquiao of his day, but..." ABS-CBN News. ABS-CBN Corporation. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- Abaya, Doroteo (1998). Miguel Malvar and the Philippine Revolution.

- Agoncillo 1990, pp. 180–181.

- Constantino 1975, p. 191

- Agoncillo 1990, p. 182

- Biak na Bato, Newsflash.org.

- Agoncillo 1990, p. 183

- Joaquin, Nick (1990). Manila, My Manila. Vera Reyes Publishing.

- Zaide 1994, p. 252

- Jose, Vicencio. Rise and Fall of Antonio Luna. Solar Publishing Corporation. pp. 225–245.

- Agoncillo, Teodoro (1960). Malolos: The Crisis of the Republic.

- Lawmaker: History wrong on Gen. Malvar at the Wayback Machine (archived April 6, 2008). January 02, 2008. manilatimes.net (archived from the original on 2008-04-06).

- "Binay seeks help from historians for overlooking Malvar as 2nd RP president". taga-ilog-news. October 24, 2011.

- "General Miguel Malvar Essay Writing Contest". Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2014-10-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "BSP issues limited edition P10-Miguel Malvar coin". Rappler. 21 December 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

Sources

- Abaya, Doroteo (1998), Miguel Malvar and the Philippine Revolution, Manila: Miguel Malvar (MM) Productions.

- Agoncillo, Teodoro A. (1990), History of the Filipino people, R.P. Garcia, ISBN 978-971-8711-06-4

- Constantino, Renato (1975), The Philippines: A Past Revisited, Quezon City: Tala Publishing Services, ISBN 971-8958-00-2.

- Zaide, Sonia M. (1994), The Philippines: A Unique Nation, All-Nations Publishing Co., ISBN 971-642-071-4

Further reading

- Zaide, Gregorio F. (1984). Philippine History and Government. National Bookstore Printing Press.

External links

- Miguel Malvar at www.geocities.com

- People and Organizations at www.geocities.com

- General Miguel Malvar at www.malvar.net

- Miguel Malvar at www.bibingka.com

- Philippine Heads of State Timeline at www.worldstatesmen.org