Bleeding Kansas

Bleeding Kansas, Bloody Kansas, or the Border War was a series of violent civil confrontations in the United States between 1854 and 1861 which emerged from a political and ideological debate over the legality of slavery in the proposed state of Kansas. The conflict was characterized by years of electoral fraud, raids, assaults, and retributive murders carried out in Kansas and neighboring Missouri by pro-slavery "Border Ruffians" and anti-slavery "Free-Staters".

At the core of the conflict was the question of whether the Kansas Territory would allow or prohibit slavery, and thus enter the Union as a slave state or a free state. The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 called for popular sovereignty, specifying that the decision about slavery would be made by popular vote of the territory's settlers, rather than by legislators in Washington. Existing sectional tensions surrounding slavery quickly found focus in Kansas. Those in favor of slavery argued that every settler had the right to bring his own property, including slaves, into the territory. In contrast, while some "Free Soil" proponents opposed slavery on religious, ethical, or humanitarian grounds, at the time the most persuasive argument against introducing slavery in Kansas was that it would allow rich slaveholders to control the land to the exclusion of poor non-slaveholders who, regardless of their moral inclinations, did not have the means to acquire either slaves or sizable land holdings for themselves.

Missouri, a slave state since 1821, was populated by many settlers with Southern sympathies and pro-slavery views, some of whom tried to influence the decision by entering Kansas and claiming to be residents. The conflict was fought politically as well as between civilians, where it eventually degenerated into brutal gang violence and paramilitary guerrilla warfare. The term "Bleeding Kansas" was popularized by Horace Greeley's New York Tribune.[2][lower-alpha 1]

Kansas was admitted to the Union as a free state on January 29, 1861, following the departure of Southern legislators from Congress during the secession crisis. Partisan violence continued along the Kansas–Missouri border for most of the war, though Union control of Kansas was never seriously threatened. Bleeding Kansas demonstrated the gravity of the era's most pressing social issues, from the matter of slavery to states' rights. Its severity made national headlines which suggested to the American people that the sectional disputes were unlikely to be resolved without bloodshed, and it therefore directly anticipated the American Civil War.[3] The episode is commemorated with numerous memorials and historic sites.

Origins

As abolitionism became increasingly popular in the United States and tensions between its supporters and detractors grew, the U.S. Congress maintained a tenuous balance of political power between Northern and Southern representatives. At the same time, the increasing emigration of Americans to the country's western frontier and the desire to build a transcontinental railroad that would connect the eastern states with California urged incorporation of the western territories into the Union. The inevitable question was how these territories would treat the issue of slavery when eventually promoted to statehood. This question had already plagued Congress during political debates following the Mexican–American War. The Compromise of 1850 had at least temporarily solved the problem by permitting residents of the Utah and New Mexico Territories to decide their own laws with respect to slavery by popular vote, an act which set a new precedent in the ongoing debate over slavery.[3]

In May 1854, the Kansas–Nebraska Act created from unorganized Indian lands the new territories of Kansas and Nebraska for settlement by U.S. citizens. The Act was proposed by Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois as a way to appease Southern representatives in Congress, who had resisted earlier proposals to organize the Nebraska Territory because they knew it must be admitted to the Union according to the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which had explicitly forbidden the practice of slavery in all U.S. territory north of 36°30' latitude and west of the Mississippi River, except in the state of Missouri. Southerners feared the incorporation of Nebraska would upset the balance between slave and free states and thereby give abolitionist Northerners an advantage in Congress.

Douglas' proposal attempted to allay these fears with the organization of two territories instead of one, as well as the inclusion of a "popular sovereignty" clause that would, like the condition previously prescribed for Utah and New Mexico, permit settlers of Kansas and Nebraska to vote on the legality of slavery in their own territories – a notion which directly contradicted and effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise. Like many others in Congress, Douglas assumed that settlers of Nebraska would ultimately vote to prohibit slavery and that settlers of Kansas, further south and closer to the slave state of Missouri, would vote to allow it, and thereby the balance of slave and free states would not change. Regarding Nebraska this assumption was correct; the idea of slavery had little appeal for Nebraska's residents and its fate as a free state was already solidly in place. In Kansas, however, the assumption of legal slavery underestimated abolitionist resistance to the repeal of the long-standing Missouri Compromise. Southerners saw the passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act as an emboldening victory; Northerners considered it an outrageous defeat. Each side of the slavery question saw a chance to assert itself in Kansas, and it quickly became the nation's prevailing ideological battleground,[4] as well as the most violent place in the country.

Early elections

Immediately, immigrants supporting both sides of the slavery question arrived in the Kansas Territory to establish residency and gain the right to vote. Among the first settlers of Kansas were citizens of slave states, especially Missouri, many of whom strongly supported Southern ideologies and emigrated to Kansas specifically to assist the expansion of slavery. Pro-slavery immigrants settled towns including Leavenworth and Atchison. The administration of President Franklin Pierce appointed territorial officials in Kansas aligned with its own pro-slavery views and, heeding rumors that the frontier was being overwhelmed by Northerners, thousands of non-resident slavery proponents soon entered Kansas with the goal of influencing local politics. Pro-slavery factions thereby captured many early territorial elections, often by fraud and intimidation. In November 1854, thousands of armed pro-slavery men known as "Border Ruffians" or "Southern Yankees", mostly from Missouri, poured into the Kansas Territory and swayed the vote in the election for a non-voting delegate to Congress in favor of pro-slavery Democratic candidate John Wilkins Whitfield.[5] The following year, a congressional committee investigating the election reported that 1,729 fraudulent votes were cast compared to 1,114 legal votes. In one location, only 20 of the 604 voters were residents of the Kansas Territory; in another, 35 were residents and 226 non-residents.[6]

At the same time, Northern abolitionists encouraged their own supporters to move to Kansas in the effort to make the territory a free state, hoping to flood Kansas with so-called "Free-Soilers" or "Free-Staters". Many citizens of Northern states arrived with assistance from benevolent societies, such as the Boston-based New England Emigrant Aid Company, founded shortly before passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act with the specific intention of assisting immigrants in reaching to the frontier. The abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher allegedly armed many of them with Sharps rifles, which became known as "Beecher's Bibles"[7] because they were shipped in wooden crates so labeled. Despite boasts that 20,000 New England Yankees would be sent to the Kansas Territory, only about 1,200 settlers had emigrated there by the end of 1855.[8][4] Nevertheless, aid movements like these, heavily publicized by the eastern press, played a significant role in propagating the nationwide hysteria over the fate of Kansas, and were directly responsible for the establishment of towns which later became strongholds of Republican and abolitionist sentiment, including Lawrence, Topeka, and Manhattan, Kansas.[4][9]

First Territorial Legislature

On March 30, 1855, the Kansas Territory held the election for its first territorial legislature.[5] Crucially, this legislature would decide whether the territory would allow slavery.[9] Just as had happened in the election of November 1854, "Border Ruffians" from Missouri again streamed into the territory to vote, and pro-slavery delegates were elected to 37 of the 39 seats – Martin F. Conway and Samuel D. Houston from Riley County were the only Free-Staters elected.[9] Due to questions about electoral fraud, Territorial Governor Andrew Reeder invalidated the results in five voting districts, and a special election was held on May 22 to elect replacements.[9] Eight of the eleven delegates elected in the special election were Free-Staters, but this still left the pro-slavery camp with an overwhelming 29–10 advantage.[9]

In response to the disputed votes and rising tension, Congress sent a three-man special committee to the Kansas Territory in 1856.[9] The committee report concluded that if the election of March 30, 1855, had been limited to "actual settlers" it would have elected a Free-State legislature.[9][10] The report also stated that the legislature actually seated "was an illegally constituted body, and had no power to pass valid laws".[9][10] Nevertheless, the pro-slavery legislature convened in the newly created territorial capital in Pawnee on July 2, 1855. The legislature immediately invalidated the results from the special election in May and seated the pro-slavery delegates elected in March. After only one week in Pawnee, the legislature moved the territorial capital to the Shawnee Mission on the Missouri border, where it reconvened, adopted a slave code for Kansas modeled largely on Missouri's own, and began passing laws favorable to slaveholders.

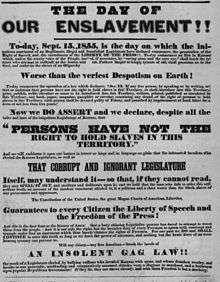

In August, anti-slavery residents met to formally reject the pro-slavery laws passed by what they called the "Bogus Legislature". They quickly elected their own Free-State delegates to a separate legislature based in Topeka, which stood in opposition to the pro-slavery government operating in Lecompton, and drafted the first territorial constitution, the Topeka Constitution. Charles L. Robinson, a Massachusetts native and agent of the New England Emigrant Aid Company, was elected territorial governor. Though the movement had a substantial backing from Northerners, and despite the findings of the Congressional committee that the pro-slavery legislature was illegally constituted, the federal government under the administration of President Franklin Pierce refused to recognize the Free-State legislature. In a message to Congress on January 24, 1856, Pierce declared the Topeka government insurrectionist in its stand against pro-slavery territorial officials.[11] The presence of dual governments was symptomatic of the strife brewing in the territory and further provoked supporters of both sides of the conflict.[12][13]

Constitutional fight

Much of the early confrontation of the Bleeding Kansas era centered on the adoption of a constitution that would govern the state of Kansas. The first of four such documents was the Topeka Constitution, written by anti-slavery forces unified under the Free-State Party in December 1855. This constitution was the basis for the Free-State territorial government that resisted the federally authorized government which had been previously elected by non-resident Missourians.[14] On June 30, 1856, following President Pierce's declaration that the Topeka government was extralegal, Congress rejected ratification of the Topeka Constitution.

Pierce was succeeded in 1857 by James Buchanan. Like his predecessor, Buchanan was a Northerner sympathetic to the South and pro-slavery interests. That year, a second constitutional convention met in Lecompton and by early November had drafted the Lecompton Constitution, a pro-slavery document endorsed by President Buchanan. The constitution was submitted to Kansans for a vote on a special slavery article, but Free-Staters refused to participate, knowing that the constitution would allow Kansas slaveholders to keep existing slaves even if the article in question was voted against. The Lecompton Constitution, including the slavery article, was approved by a vote of 6,226 to 569 on December 21. Congress instead ordered another election because of voting irregularities uncovered. On August 2, 1858, Kansas voters rejected the document by 11,812 to 1,926.[15]

While the Lecompton Constitution was pending before Congress, a third document, the Leavenworth Constitution, was written and passed by Free-State delegates. It was more radical than other Free-State proposals in that it would have extended suffrage to "every male citizen", regardless of race. Participation in this ballot on May 18, 1858, was a fraction of the previous and there was even some opposition by Free-State Democrats. The proposed constitution was forwarded to the U.S. Senate on January 6, 1859, where it was met with a tepid reception and left to die in committee.[16]

The fourth and final Free-State proposal was the Wyandotte Constitution, drafted in 1859, which represented the anti-slavery view of the future of Kansas. It was approved in a referendum by a vote of 10,421 to 5,530 on October 4, 1859.[17] With Southern states still in control of the Senate, confirmation of the Wyandotte Constitution was indefinitely postponed, and Kansas awaited admission to the Union until 1861, when the Southern legislators had left.

Open violence

On November 21, 1855, the so-called Wakarusa War began in Douglas County when a pro-slavery settler, Franklin Coleman, shot and killed a Free-Stater, Charles Dow, with whom Coleman had long been engaged in a feud that was unrelated to local or national politics. Dow was the first American settler to be murdered in the Kansas Territory. The decision by Douglas County Sheriff Samuel J. Jones to arrest another Free-Stater rather than Coleman and the prisoner's subsequent rescue by a Free-State posse erupted into a conflict that pitted, for the first time, armed pro-slavery settlers against anti-slavery settlers. Governor Wilson Shannon called for the Kansas militia, but the assembled army was composed almost entirely of pro-slavery Missourians, who camped outside the town of Lawrence with stolen weapons and a cannon.

In response, Lawrence raised its own militia led by Charles L. Robinson, the man elected governor by the Topeka legislature, and James H. Lane. The parties besieging Lawrence reluctantly dispersed only after Shannon negotiated a peace treaty between Robinson and Lane and David Rice Atchison. The conflict had one other fatality, when Free-Stater Thomas Barber was shot and killed near Lawrence on December 6.

Summer of 1856

On May 21, 1856, pro-slavery Democrats and Missourians invaded Lawrence, Kansas and burned the Free State Hotel, destroyed two anti-slavery newspaper offices, and ransacked homes and stores in what became known as the Sacking of Lawrence.[18] A cannon used during the Mexican–American War, called the Old Kickapoo or Kickapoo Cannon, was stolen and used on that day by a pro-slavery group including the Kickapoo Rangers of the Kansas Territorial Militia.[19] It was later recovered by an anti-slavery faction and returned to the city of Leavenworth.[19][20][21]

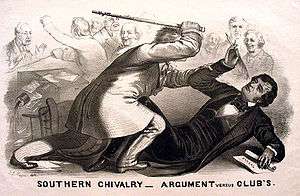

In May 1856, Republican Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts took to the floor to denounce the threat of slavery in Kansas and humiliate its supporters. Sumner accused Democrats in support of slavery of lying in bed with "the harlot of slavery" on the House floor during his "Crimes Against Kansas" speech.[22] He had devoted his enormous energies to the destruction of what Republicans called the Slave Power, that is the efforts of slave owners to control of the federal government and ensure the both the survival and the expansion of slavery. In the speech (called "The Crime against Kansas") Sumner ridiculed the honor of elderly South Carolina Senator Andrew Butler, portraying Butler's pro-slavery agenda towards Kansas with the raping of a virgin, and characterizing his affection for it in sexual and revolting terms.[23] The next day, Butler's cousin, the South Carolina Congressman Preston Brooks, nearly killed Sumner on the Senate floor with a heavy cane. The action electrified the nation, brought violence to the floor of the Senate, and deepened the North-South split.[24] After nearly killing Sumner, Brooks was praised by Southern Democrats for the attack. Many pro-slavery newspapers concluded that abolitionists in Kansas and beyond "must be lashed into submission," and hundreds of Southern Democrat lawmakers after the attack sent Brooks new canes as an endorsement of the attack, with one of the canes being inscribed with the phrase "hit him again." Two weeks after the attack, American philosopher and Harvard graduate Ralph Waldo Emerson condemned Brooks and the pro-slavery lawmakers, stating: "I do not see how a barbarous community and a civilized community can constitute one state. I think we must get rid of slavery, or we must get rid of freedom." In the coming weeks, many pro-slavery Democrats wore necklaces made from broken pieces of the cane as a symbol of solidarity with Preston Brooks.[25]

The violence continued to increase. John Brown led his sons and other followers to plan the murder of settlers who spoke in favor of slavery. At a pro-slavery settlement at Pottawatomie Creek on the night of May 24, the group seized five pro-slavery men from their homes and hacked them to death with broadswords. Brown and his men escaped and began plotting a full-scale slave insurrection to take place at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, with financial support from Boston abolitionists.[26]

The pro-slavery territorial government, serving under President Pierce, had been relocated to Lecompton. In April 1856, a Congressional committee arrived there to investigate voting fraud. The committee found the elections improperly elected by non-residents. President Pierce refused recognition of its findings and continued to authorize the pro-slavery legislature, which the Free State people called the "Bogus Legislature."

On July 4, 1856, proclamations of President Pierce led to nearly 500 U.S. Army troops arriving in Topeka from Fort Leavenworth and Fort Riley. With their cannons pointed at Constitution Hall and the long fuses lit, Colonel E.V. Sumner, cousin to the senator of the same name beaten on the Senate floor, ordered the dispersal of the Free State Legislature.[27]

In August 1856, thousands of pro-slavery men formed into armies and marched into Kansas. That same month, Brown and several of his followers engaged 400 pro-slavery soldiers in the Battle of Osawatomie. The hostilities raged for another two months until Brown departed the Kansas Territory, and a new territorial governor, John W. Geary, took office and managed to prevail upon both sides for peace.

1857–1861

This was followed by a fragile peace broken by intermittent violent outbreaks for two more years. The last major outbreak of violence was touched off by the Marais des Cygnes massacre in 1858, in which Border Ruffians killed five Free State men. In the so-called Battle of the Spurs, in January, 1859, John Brown led escaped slaves through a pro-slavery ambush en route to freedom via Nebraska and Iowa; not a shot was fired. However, approximately 56 people died in Bleeding Kansas by the time the violence ended in 1859.[1]

American Civil War

The Congressional legislative deadlock was broken in early 1861 when, following the election of Abraham Lincoln as President, seven Southern states seceded from the Union and withdrew their delegations from Congress. Kansas was promptly admitted to the Union as a free state under the Wyandotte Constitution. While pro-Confederates in Missouri attempted to effect that state's secession from the Union and succeeded in having a pro-Confederate government recognized by and admitted to the Confederacy, by the end of 1861 even that state was firmly in control of its Unionist government. Without control of Missouri, regular Confederate forces were never in a position to seriously threaten the newly-recognized free state government in Kansas.

Nevertheless, following the commencement of the American Civil War in 1861, additional guerrilla violence erupted on the border between Kansas and Missouri and would sporadically continue until the end of the war.

Legacy

Heritage Area

In 2006, federal legislation defined a new Freedom's Frontier National Heritage Area (FFNHA) and was approved by Congress. A task of the heritage area is to interpret Bleeding Kansas stories, which are also called stories of the Kansas–Missouri border war. A theme of the heritage area is the enduring struggle for freedom. FFNHA includes 41 counties, 29 of which are in eastern Kansas and 12 in western Missouri.[28]

In popular culture

The "Bleeding Kansas" period has been dramatically rendered in countless works of American popular culture, including literature, theater, film, and television. Its many depictions and mentions include:

- Sante Fe Trail (1940), an American western film set before the Civil War which depicts John Brown's campaign during Bleeding Kansas, starring Ronald Reagan, Errol Flynn, and Raymond Massey.

- Wildwood Boys (William Morrow, New York; 2000), a biographical novel of "Bloody Bill" Anderson by James Carlos Blake

- Bleeding Kansas (2008) by Sara Paretsky, a novel depicting social and political conflicts in present-day Kansas with many references to the 19th-century events

- The Good Lord Bird (2013), book by James McBride

- The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), an American western film set during and after the Civil War which depicts violence in the aftermath of Bleeding Kansas. The character of Granny, who is from Kansas, had a son whom she said "was killed by Missouri ruffians in The Border War".

- Bad Blood, the Border War that Triggered the Civil War (2007), a documentary film (ISBN 0-9777261-4-2) by Kansas City Public Television and Wide Awake Films

- The November 8, 2014, episode of Hell on Wheels, titled "Bleeding Kansas", depicted one occurrence of a white family being slain for having slaves, who were then freed, in the name of religion[29]

- When Kings Reigned (2017), a docudrama directed by Ian Ballinger and Alison Dover about fishermen living along the Kansas River during and after the Bleeding Kansas era and the persecution they faced from local governments

- The Kents, a 12 issue mini-series of comics written by John Ostrander exploring the history of Superman's adoptive family set against the conflicts of the Bleeding Kansas era.

Notes

- The Tribunes first reference to "Kansas, bleeding," came on June 16, 1856, in a report on the North American National Convention. There a Colonel Perry of Kansas reported that "Kansas, bleeding at every pore, would cast more votes indirectly for [the presidential candidate the convention settled upon] . . . than any other State in the Union.” (Source: "Public Meetings. North American National Convention. Third Day." New York Daily Tribune, June 16, 1856.)[2]

The Tribune's first mention of "bleeding Kansas" was in a poem by Charles S. Weyman, published in the newspaper on September 13, 1856:

Far in the West rolls the thunder—

The tumult of battle is raging

Where bleeding Kansas is waging

War against Slavery!

(Source: "Fremont and Victory. The Prize Song By Charles S. Weyman." New York Daily Tribune. September 13, 1856.)[2]

References

- "Watts, Dale. "How Bloody Was Bleeding Kansas? Political Killings in Kansas territory, 1854–1861", Kansas History (1995) 18#2 pgs. 116–29" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-07-30. Retrieved 2009-01-09.

- Denial, Catherine. "Bleeding Kansas". teachinghistory.org. National History Education Clearinghouse. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- Etcheson, Nicole. "Bleeding Kansas: From the Kansas-Nebraska Act to Harpers Ferry". Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854–1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Archived from the original on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- Rawley, James A. (1969). Race & Politics: "Bleeding Kansas" and the Coming of the Civil War. J. B. Lippincott Company.

- "Territorial Politics and Government". Territorial Kansas Online. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- Cutler, William G. History of the State of Kansas, A.T. Andreas, (1883), "Territorial History, Part 8".

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-02-10. Retrieved 2019-02-21.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- William Frank Zornow, "Kansas: a history of the Jayhawk State" (1957), pg. 72

- Olson, Kevin (2012). Frontier Manhattan. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1832-3.

- Report of the special committee appointed to investigate the troubles in Kansas, Cornelius Wendell, 1856, archived from the original on August 11, 2011, retrieved June 18, 2014

- Richardson, James D. "A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents". Project Gutenberg. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2008-03-18.

- Thomas Goodrich, War to the Knife: Bleeding Kansas, 1854–1861. (2004). Ch. 1 iii.

- Elizabeth R. Varon, Disunion! The Coming of the American Civil War, 1789–1859. (2007). Ch. 8.

- Cutler, William G. History of the State of Kansas, A.T. Andreas, (1883), "Territorial History".

- Cutler, William G. "Territorial History, Part 55".

- Cutler, William G. "Territorial History, Part 53".

- "Wyandotte Constitution Approved". Archived from the original on 2014-11-05. Retrieved 2014-11-05.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-02-15. Retrieved 2019-02-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Kansas Historical Society (February 2017). "Old Kickapoo Cannon". Kansapedia – Kansas Historical Society. Archived from the original on May 15, 2018. Retrieved June 1, 2018.

- Lull, Robert W. "Civil War General and Indian Fighter James M. Williams: Leader of the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry and the 8th U.S. Cavalry". University of North Texas Press – via Google Books.

- "Kickapoo Cannon". Blackmar's Cyclopedia of Kansas History. 1912. p. 69. Archived from the original on May 15, 2018. Retrieved June 1, 2018 – via Kansas State History.

- "The Caning of Senator Charles Sumner (May 22, 1856)". United States Senate. Archived from the original on 2019-02-07. Retrieved 2019-02-07.

- Pfau, Michael William (2003). "Time, Tropes, and Textuality: Reading Republicanism in Charles Sumner's 'Crime Against Kansas'". Rhetoric & Public Affairs. 6 (3): 393. doi:10.1353/rap.2003.0070.

- Williamjames Hull Hoffer, The Caning of Charles Sumner: Honor, Idealism, and the Origins of the Civil War (2010)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-02-09. Retrieved 2019-02-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Schraff, Anne E. (2010). John Brown: "We Came to Free the Slaves". Enslow. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-7660-3355-9. Archived from the original on 2016-05-11.

- Thomas K. Tate (2013). General Edwin Vose Sumner, USA: A Civil War Biography. McFarland. p. 53. ISBN 9780786472581. Archived from the original on 2016-05-03. Retrieved 2015-12-11.

- Freedom's Frontier National Heritage Area Management Plan Appendices Archived 2014-11-29 at the Wayback Machine, Freedomsfrontier.org/

- "Hell on Wheels Season 4 Episode 11 Review: Bleeding Kansas". Archived from the original on 2014-11-09. Retrieved 2014-11-09.

Further reading

- Childers, Christopher. "Interpreting Popular Sovereignty: A Historiographical Essay", Civil War History Volume 57, Number 1, March 2011 pp. 48–70 in Project MUSE

- Earle, Jonathan and Burke, Diane Mutti. Bleeding Kansas, Bleeding Missouri: The Long Civil War on the Border. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2013.

- Etcheson, Nicole. "The Great Principle of Self-Government: Popular Sovereignty and Bleeding Kansas", Kansas History 27 (Spring-Summer 2004):14–29, links it to Jacksonian Democracy

- Etcheson, Nicole. Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era (2006)

- Goodrich, Thomas. War to the Knife: Bleeding Kansas, 1854–1861 (2004)

- Johannsen, Robert W. "Popular Sovereignty and the Territories", Historian 22#4 pp. 378–395, doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1960.tb01665.x

- Malin, James C. John Brown and the Legend of Fifty-six. (1942)

- Miner, Craig (2002). Kansas: The History of the Sunflower State, 1854–2000.

- Nevins, Alan. Ordeal of the Union: vol. 2 A House Dividing, 1852–1857 (1947), Kansas in national context

- Nichols, Roy F. "The Kansas–Nebraska Act: A Century of Historiography", Mississippi Valley Historical Review (1956) 43#2 pp. 187–212 in JSTOR

- Potter, David. The Impending Crisis, 1848–1861 (1976), Pulitzer Prize; ch 9, 12

- Reynolds, David (2005). John Brown, Abolitionist.

- SenGupta, Gunja (March 1993). "'A Model New England State': Northeastern Antislavery in Territorial Kansas, 1854-1860". Civil War History. 39 (1). pp. 31–46. doi:10.1353/cwh.1993.0057.

- Address to the people of the United States, together with the proceedings and resolutions of the Pro-slavery Convention of Missouri, held at Lexington, July, 1855. St. Louis, Missouri. 1855.

External links

- 1856 Congressional Report on the Troubles in Kansas

- Documentary On Bleeding Kansas

- Kansas State Historical Society: A Look Back at Kansas Territory, 1854–1861

- Access documents, photographs, and other primary sources on Kansas Memory, the Kansas State Historical Society's digital portal

- NEEAC. History of the New-England Emigrant Aid Company. Boston: John Wilson & Son, 1862.

- PBS article on Bleeding Kansas.

- Territorial Kansas Online: A Virtual Repository for Kansas Territorial History.

- U-S-History.com.

- Online Exhibit – Willing to Die for Freedom, Kansas Historical Society

- Map of North America during Bleeding Kansas at omniatlas.com

.svg.png)