Bolo knife

A bolo (Tagalog: iták, Ilocano: bunéng, Cebuano: súndang, Hiligaynon: binangon) is a large cutting tool of Filipino origin similar to the machete. It is used particularly in the Philippines, the jungles of Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei, as well as in the sugar fields of Cuba.

| Bolo | |

|---|---|

Top: A typical bolo from Luzon; Bottom: Lumad bolos with sheaths from Mindanao in the National Museum of Anthropology | |

| Type | Knife or sword |

| Place of origin | Philippines |

| Service history | |

| Wars | |

| Specifications | |

| Blade type | Single-edged, convex blade |

| Hilt type | hardwood, carabao horn |

| Scabbard/sheath | hardwood, carabao horn |

The primary use for the bolo is clearing vegetation, whether for agriculture[1][2] or during trail blazing. The bolo is also used in Filipino martial arts or Arnis as part of training.[3][4][5]

Common use

The bolo is common in the countryside due to its use as a farming implement. As such, it was used extensively during Spanish colonial rule as a manual alternative to ploughing with a carabao. Normally used for cutting coconuts,[1] it was also a common harvesting tool for narrow row crops found on terraces such as rice, mungbeans, soybeans, and peanuts.[6] Because of its availability, the bolo became a common choice of improvised weaponry to the everyday peasant.[7]

Design

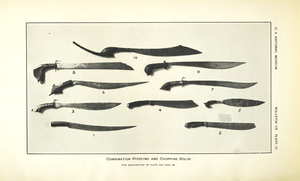

Bolos are characterized by having a native hardwood or animal horn handle (such as from the carabao),[8] a full tang, and by a steel blade that both curves and widens, often considerably so, at its tip.[1][5] This moves the centre of gravity as far forward as possible, giving the bolo extra momentum for chopping.[8]

So-called "jungle bolos", intended for combat rather than agricultural work, tend to be longer and less wide at the tip.[1][5] Bolos for gardening usually have rounded tips.[8]

Types

The term "bolo" has also expanded to include other traditional blades that primarily or secondarily function as agricultural implements. They include:

- Barong - a leaf-shaped sword or knife favored by the Tausug people.

- Batangas - a single-edged bolo from the Tagalog people that widens at the tip.

- Garab - a sickle used for harvesting rice.

- Guna or Bolo-guna - A weeding knife with a very short and wide dull blade with a perpendicular blunt end. It is used mainly for digging roots and weeding gardens

- Kampilan or Talibong - a tapering long sword found throughout the Philippines

- Iták - a narrow sword used for used for combat and self-defense in the Tagalog regions. Like the súndang, it is also known as the "jungle bolo" or "tip bolo", and was a popular weapon during the Philippine Revolution and the Philippine-American War.

- Haras - a scythe used for cutting tall grass. It is called "Lampas" by people from Mindanao.

- Pinuti - a narrow sword traditionally carried as a personal weapon for combat or self-defense.

- Pirah or Pira - a wide-tipped sword or knife favored by the Yakan people, but is also found throughout the Sulu Archipelago, Mindanao, and the Visayas.

- Punyal or Gunong - a dagger derivative of the kalis. Used as a side-weapon in combat or to kill and bleed pigs during slaughter. Also known under the more general term kutsilyo (Spanish cuchillo, "knife").

- Súndang - the most common personal weapon used for combat and self-defense in the Visayas. Also known as the "jungle bolo" or "tip bolo". It was a popular weapon of choice in the Philippine Revolution against the Spanish Empire and during the subsequent Philippine–American War.

- Binangon - A form of súndang used in Western Visayas and Negros Island.

Historical significance

It has been claimed by some historians that Lapu-Lapu, during the Battle of Mactan, brandished a kampilan to kill Portuguese circumnavigator Ferdinand Magellan, though other historians dispute this. The bolo was the primary weapon used by the Katipunan during the Philippine Revolution.[5][9] It was also used by the Filipino guerrillas and bolomen during the Philippine–American War.[1][2][5][10]

During World War I, United States Army soldier Henry Johnson gained international fame repelling a German raid in hand-to-hand combat using a bolo.[11]

During World War II, the 1st Filipino Regiment was called the Bolo Battalion and used bolos for close quarters combat.[5][12]

On 7 December 1972, would-be assassin Carlito Dimahilig used a bolo to attack former First Lady Imelda Marcos as she appeared onstage at a live televised awards ceremony. Dimahilig stabbed Marcos in the abdomen several times, and she parried the blows with her arms. He was shot dead by security forces while she was taken to a hospital.[13][14]

Symbolism

The bolo serves as a symbol for the Katipunan and the Philippine Revolution, particularly the Cry of Pugad Lawin. Several monuments of Andres Bonifacio, as with other notable Katipuneros, depict him holding a bolo in one hand and the Katipunan flag in the other.[9][15]

Other uses of the term

In the United States Military, the slang term "to bolo" – to fail a test, exam or evaluation, originated from the combined Philippine-American military forces including recognized guerrillas during the Spanish–American War and the Philippine–American War; those local soldiers and guerrillas who failed to demonstrate proficiency in marksmanship were issued bolos instead of firearms so as not to waste scarce ammunition.[16]

In hand-to-hand combat sports, especially boxing, the term "bolo punch" is used to describe an uppercut thrown in a manner mimicking the arcing motion of a bolo while in use.[17]

Gallery

.jpg)

.jpg) Bolo given to Captain Lewis A. Kimberly, Commander of USS Beneica by the Governor of Cebu

Bolo given to Captain Lewis A. Kimberly, Commander of USS Beneica by the Governor of Cebu- A pinahig utility bolo of the Ifugao people

A modern bolo

A modern bolo_making_(9275225915).jpg) Traditional blacksmiths forging a bolo

Traditional blacksmiths forging a bolo

See also

- Cane knife

- Dahong palay

- Golok

- Kalis (also called "sundang" in eastern Indonesia)

- Kukri

- Machete

- Operation: BOLO- An American military operation during the Vietnam War

- Parang

References

- Valderrama, Michael R. (22 June 2013). "The bolo". Sun.Star Bacolod. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- Mallari, Perry Gil S. (14 June 2014). "The Bolomen of the Revolution". The Manila Times. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- Green, ed. by Thomas A. (2001). Martial Arts of the World. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 429. ISBN 1-57607-150-2. Retrieved 12 November 2014.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "Eskrima Martial Arts". Doce Pares International. 28 May 2014. Archived from the original on 20 July 2014. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- Wolfgang, Bethge (2007). "The Bolo – An indispensable Utensil in the Philippine Household". Insights-Philippines.de. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- Small Farm Equipment for Developing Countries: Proceedings of the International Conference on Small Farm Equipment for Developing Countries: Past Experiences and Future Priorities, 2-6 September 1985. Manila, Philippines: International Rice Research Institute. 1986. p. 314. ISBN 9789711041571.

- "Military Fighting Knives of the World". MilitaryItems.com. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- "Bolo Knife". Reflections of Asia. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- "Imprinting Andres Bonifacio: The Iconization from Portrait to Peso". Republic of the Philippines: Presidential Museum Library. 29 November 2012. Archived from the original on 11 September 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- Dumindin, Arnaldo (2006). "Philippine–American War, 1899–1902". PhilippineAmericanWar. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- Lamothe, Dan (2 June 2015). "Army discovers sad surprise in family history of new Medal of Honor recipient Henry Johnson". Washington Post. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- Ruiz, AJ (13 July 2012). "Pinoy Patriots". Bakitwhy.com. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- Fetherling, George (2001). A Biographical Dictionary of the World's Assassins (Unabridged. ed.). Toronto: Random House Canada. ISBN 0-307-36909-9. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- "Profiling Imelda Marcos: 10 Reasons She's Still Here". Oh No They Didn't!. 22 September 2010. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- "The Bonifacio Monument: Hail to the Chief!". Filipinas Heritage Library. The FHL Research Team. 12 November 2003. Archived from the original on 3 December 2003. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- "Spanish–American War slang". Patriotfiles.com. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- "Historical Dictionary of Boxing". Scarecrow Press, Inc. Retrieved 19 June 2020.