Darjeeling

Darjeeling (Bengali: [ˈdarˌdʒiliŋ], Nepali: [darˈdziːliŋ]) is a city and a municipality in the Indian state of West Bengal. It is located in the Lesser Himalayas at an elevation of 2,000 metres (6,700 ft). It is noted for its tea industry, its views of Kangchenjunga, the world's third-highest mountain, and the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Darjeeling is the headquarters of the Darjeeling district which has a partially autonomous status called Gorkhaland Territorial Administration within the state of West Bengal. It is also a popular tourist destination in India.

Darjeeling | |

|---|---|

City | |

A view of Darjeeling from the Happy Valley Tea Estate | |

| Nickname(s): The Queen of Hills | |

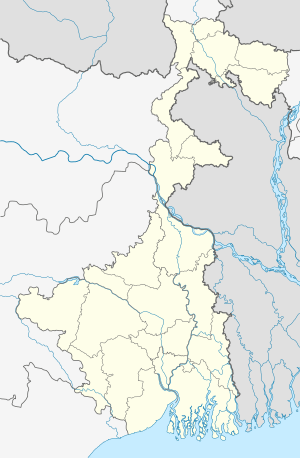

Darjeeling Location in West Bengal, India  Darjeeling Darjeeling (India) | |

| Coordinates: 27°3′N 88°16′E | |

| Country | |

| State | West Bengal |

| District | Darjeeling |

| Settled | 1815, Treaty of Sugauli |

| Founded by | East India Company |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipal Corporations in India |

| • Body | Darjeeling Municipality |

| • Chairman | Pratibha Rai[1] |

| • Vice-Chairman | Sagar Tamang |

| Area | |

| • Total | 10.57 km2 (4.08 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 2,042.16 m (6,700.00 ft) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 132,016 |

| • Density | 12,000/km2 (32,000/sq mi) |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Bengali and Nepali[3] |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| Postal Index Number | 734101 |

| Telephone code | 0354 |

| Vehicle registration | WB-76 WB-77 |

| Lok Sabha constituency | Darjeeling |

| Vidhan Sabha constituency | Darjeeling |

| Website | darjeelingmunicipality |

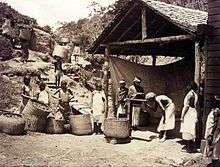

The recorded history of the town starts from the early 19th century when the colonial administration under the British Raj set up a sanatorium and a military depot in the region. Subsequently, extensive tea plantations were established in the region and tea growers developed hybrids of black tea and created new fermentation techniques. The resultant distinctive Darjeeling tea is internationally recognised and ranks among the most popular black teas in the world.[4] The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway connects the town with the plains and has some of the few steam locomotives still in service in India.

Darjeeling has several British-style private schools, which attract pupils from all over India and a few neighbouring countries. The varied culture of the town reflects its diverse demographic milieu comprising Lepcha, Khampa, Gorkha, Newar, Sherpa, Bhutia, Bengali[5] and other mainland Indian ethno-linguistic groups. Darjeeling, alongside its neighbouring town of Kalimpong, was the centre of the Gorkhaland social movement in the 1980s and summer 2017.

Toponymy

The etymological term of the Darjeeling is denoted " Tajenglung" a Yakthung limbu terminology means the stones which are "talk to each other" according to the historian Sankarhang Subba of Darjeeling.[6] The name Darjeeling acclaimed from the Tibetan words Dorje, which is the thunderbolt sceptre of the Hindu deity Indra, and ling, which means "a place" or "land".[7]

|

| Darjeeling TE: tea estate, F: facility, T: religious place, I: institute Abbreviations used in names – TE for Tea Estate Owing to space constraints in the small map, the actual locations in a larger map may vary slightly All places marked in the map are linked in the larger full screen map |

History

The history of Darjeeling is intertwined with that of Sikkim, Nepal, British India, and Bhutan. Until the early 19th century, the hilly area around Darjeeling was controlled by the Kingdom of Sikkim[8] with the settlement consisting of a few villages of the Lepcha and Kirati people.[9] The Chogyal of Sikkim had been engaged in unsuccessful warfare against the Gurkhas of Nepal. The territory of Darjeeling and its history goes on back to the Yakthung Limbuwan Laje kingdom anciently. After the treaty of Sugoulee in 1816 CE between the Gorkha king and East India Company led to be ceded to the Sikkim through the British India. The territory of Yakthung Laje Limbuwan and as per the Darjeeling included within it that become pseudo land of Sikkim while it was not ruled by Sikkim but remained as leasehold land for long time. The Yakhung Limbu Kings and Gorkha King made treaty of salt and water in 1774 CE but it was violated by Gorkha Kings on the treaty of Sugoulee while Limbu rulers were not attended in the treaty. It means the territory between the west of Arun river and east of Teesta river and the land areas within it all are Yakthung Laje Limbuwan.[10]

From 1780, the Gurkhas made several attempts to capture the entire region of Darjeeling. By the beginning of the 19th century, they had overrun Sikkim as far eastward as the Teesta River and had conquered and annexed the Terai and the entire area now belonged to Nepal.[11] In the meantime, the British Army was engaged in preventing the Gorkhas from over-running the whole of the northern frontier. The Anglo-Nepalese War war broke out in 1814, which resulted in the defeat of the Gurkhas and subsequently led to the signing of the Sugauli Treaty in 1816. According to the treaty, Nepal had to cede all those territories annexed from the Chogyal of Sikkim to the British East India Company (i.e. the area between Mechi River and Teesta River). Later in 1817, through the Treaty of Titalia, the British East India Company reinstated the Chogyal of Sikkim, restored all the tracts of land between the River Mechi and the River Teesta to the Chogyal of Sikkim and guaranteed his sovereignty.[12]

In 1828, a delegation of the British East India Company (BEIC) officials on its way to the Nepal-Sikkim border stayed in Darjeeling and decided that the region was a suitable site for a sanatorium for British soldiers.[13][14] The company negotiated a lease of the area west of the Mahananda River from the Chogyal of Sikkim in 1835.[15] In 1849, the BEIC Superintendent Archibald Campbell and the explorer and botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker were imprisoned in the region by the Sikkim Chogyal. The BEIC sent a force to free them. Continued friction between the BEIC and the Sikkim authorities resulted in the annexation of 1,700 square kilometres (640 sq mi) of territory by the British in 1850. In 1864, the Bhutanese rulers and the British signed the Treaty of Sinchula that ceded the passes leading through the hills and Kalimpong to the British.[12] Further discord between Sikkim and the British resulted in a war, culminating in the signing of a treaty and the annexation by the British of the area east of the Teesta River in 1865.[16] By 1866, Darjeeling district had assumed its current shape and size, covering an area of 3,200 square kilometres (1,234 sq mi).[12]

During the British Raj, Darjeeling's temperate climate led to its development as a hill station for British residents seeking to escape the summer heat of the plains. The development of Darjeeling as a sanatorium and health resort proceeded briskly.[9] Arthur Campbell, a surgeon with the Company, and Lieutenant Robert Napier were responsible for establishing a hill station there. Campbell's efforts to develop the station, attract immigrants to cultivate the slopes and stimulate trade resulted in a hundredfold increase in the population of Darjeeling between 1835 and 1849.[12][17] The first road connecting the town with the plains was constructed between 1839 and 1842.[9][17] In 1848, a military depot was set up for British soldiers, and the town became a municipality in 1850.[17]

Commercial cultivation of tea in the district began in 1856, and induced a number of British planters to settle there.[13] Darjeeling became the formal summer capital of the Bengal Presidency after 1864.[18] Scottish missionaries undertook the construction of schools and welfare centres for the British residents, laying the foundation for Darjeeling's notability as a centre of education. The opening of the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway in 1881 further hastened the development of the region.[19] In 1899, Darjeeling was rocked by major landslides that caused severe damage to the town and the native population.[20]

.jpg)

Under the British Raj, the Darjeeling area was initially a "Non-Regulation District", a scheme of administration applicable to economically less advanced districts in the British India; acts and regulations of the British Raj did not automatically apply to the district in line with rest of the country. In 1919, the area was declared a "backward tract".[21]

During the Indian independence movement, the Non-cooperation movement spread through the tea estates of Darjeeling.[22] There was also a failed assassination attempt by revolutionaries on John Anderson, the Governor of Bengal in 1934.[23] Subsequently, during the 1940s, communist activists continued the nationalist movement against the British by mobilising the plantation workers and the peasants of the district.[24]

Socio-economic problems of the region that had not been addressed during British Raj continued to linger and were reflected in a representation made to the Constituent Assembly of India in 1947, which highlighted the issues of regional autonomy and Nepali nationality in Darjeeling and adjacent areas.[24] After the independence of India in 1947, Darjeeling was merged with the state of West Bengal. A separate district of Darjeeling was established consisting of the hill towns of Darjeeling, Kurseong, Kalimpong and some parts of the Terai region. While the hill population comprised mainly ethnic Nepalis, the plains harboured a large ethnic Bengali population who were refugees from the Partition of India.[25] A cautious and non-receptive response by the West Bengal government to most demands of the ethnic Nepali population led to increased calls, in the 1950s and 1960s, for Darjeeling's autonomy and for the recognition of the Nepali language; the state government acceded to the latter demand in 1961.[26]

The creation of a new state of Sikkim in 1975, along with the reluctance of the Government of India to recognise Nepali as an official language under the Constitution of India, brought the Gorkhaland movement to the forefront.[27] Agitation for a separate state continued through the 1980s,[28] included violent protests during the 1986–88 period. The agitation ceased only after an agreement between the government and the Gorkha National Liberation Front (GNLF), resulting in the establishment of an elected body in 1988 called the Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council (DGHC), which received autonomy to govern the district. Though Darjeeling became peaceful, the issue of a separate state lingered, fuelled in part by the lack of comprehensive economic development in the region even after the formation of the DGHC.[29] New protests erupted in 2008–09, but both the Union and State governments rejected Gorkha Janmukti Morcha's (GJM) demand for a separate state.[30] In July 2011, a pact was signed between GJM, the Government of West Bengal and the Government of India which includes the formation of a new autonomous, elected Gorkhaland Territorial Administration (GTA), a hill council endowed with more powers than its predecessor Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council.[31]

Geography

Darjeeling is the main town of the Sadar subdivision and also the headquarters of the district. It is located at an elevation of 2,000 m (6,700 ft)[2] in the Darjeeling Himalayan hill region on the Darjeeling-Jalapahar range that originates in the south from Ghum. The range is Y-shaped with the base resting at Katapahar and Jalapahar and two arms diverging north of the Observatory Hill. The north-eastern arm dips suddenly and ends in the Lebong spur, while the north-western arm passes through North Point and ends in the valley near Tukver Tea Estate.[32] The hills are nestled within higher peaks and the snow-clad Himalayan ranges tower over the town in the distance. Kanchenjunga, the world's third-highest peak, 8,598 m (28,209 ft) high, is the most prominent mountain visible. On clear days Nepal's Mount Everest, 8,850 m (29,035 ft) high, can be seen.[33]

The hills of Darjeeling are part of the Lesser Himalaya. The soil is chiefly composed of sandstone and conglomerate formations, which are the solidified and upheaved detritus of the great range of Himalaya. However, the soil is often poorly consolidated (the permeable sediments of the region do not retain water between rains) and is not considered suitable for agriculture. The area has steep slopes and loose topsoil, leading to frequent landslides during the monsoons. According to the Bureau of Indian Standards, the town falls under seismic zone-IV, (on a scale of I to V, in order of increasing proneness to earthquakes) near the convergent boundary of the Indian and the Eurasian tectonic plates and is subject to frequent earthquakes.[33]

Climate

| Climate data for Darjeeling (1981–2010, extremes 1901–2012) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.9 (66.0) |

19.2 (66.6) |

24.0 (75.2) |

26.7 (80.1) |

25.7 (78.3) |

27.7 (81.9) |

28.0 (82.4) |

28.5 (83.3) |

27.5 (81.5) |

26.0 (78.8) |

24.5 (76.1) |

20.0 (68.0) |

28.5 (83.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 10.7 (51.3) |

12.4 (54.3) |

15.6 (60.1) |

18.5 (65.3) |

19.3 (66.7) |

19.8 (67.6) |

19.6 (67.3) |

20.0 (68.0) |

19.8 (67.6) |

19.5 (67.1) |

17.1 (62.8) |

14.0 (57.2) |

17.2 (63.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.5 (34.7) |

2.9 (37.2) |

5.7 (42.3) |

8.8 (47.8) |

10.6 (51.1) |

12.8 (55.0) |

13.4 (56.1) |

13.4 (56.1) |

12.4 (54.3) |

10.5 (50.9) |

6.3 (43.3) |

3.8 (38.8) |

8.5 (47.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7.2 (19.0) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

0.0 (32.0) |

1.4 (34.5) |

6.6 (43.9) |

3.9 (39.0) |

8.0 (46.4) |

6.2 (43.2) |

3.2 (37.8) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−4.6 (23.7) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 13.5 (0.53) |

14.0 (0.55) |

30.8 (1.21) |

76.9 (3.03) |

137.9 (5.43) |

466.0 (18.35) |

656.7 (25.85) |

528.2 (20.80) |

379.7 (14.95) |

59.1 (2.33) |

14.4 (0.57) |

2.9 (0.11) |

2,380 (93.70) |

| Average rainy days | 1.1 | 1.5 | 2.8 | 6.8 | 10.5 | 18.8 | 22.9 | 21.7 | 14.9 | 2.9 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 105.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 17:30 IST) | 81 | 78 | 75 | 78 | 88 | 93 | 94 | 92 | 90 | 84 | 75 | 74 | 84 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 167.4 | 141.3 | 145.7 | 147.0 | 151.9 | 72.0 | 77.5 | 102.3 | 96.0 | 167.4 | 189.0 | 189.1 | 1,646.6 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 5.4 | 5.0 | 4.7 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 5.4 | 6.3 | 6.1 | 4.5 |

| Source 1: India Meteorological Department[34][35] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (sun 1891–1990)[36] | |||||||||||||

Darjeeling has a temperate climate (Köppen: Cwb,[37] subtropical highland climate) with wet summers caused by monsoon rains.[38] The annual mean maximum temperature is 14.9 °C (58.8 °F) while the mean minimum temperature is 8.9 °C (48.0 °F),[2] with monthly mean temperatures ranging from 6 to 18 °C (43 to 64 °F).[37] The lowest temperature recorded was −5 °C (23 °F) on 11 February 1905.[2] The average annual precipitation is 3,092 mm (121.7 in), with an average of 126 days of rain in a year.[2] The highest rainfall occurs in July.[34][37] The heavy and concentrated rainfall that is experienced in the region, aggravated by deforestation and haphazard planning, often causes devastating landslides, leading to loss of life and property.[39][40] Though not very common, the town receives snow at least once during two winter months of December and January.[41]

Flora and fauna

Darjeeling is a part of the Eastern Himalayan zoo-geographic zone.[42] Flora around Darjeeling comprises sal, oak, semi-evergreen, temperate and alpine forests.[43] Dense evergreen forests of sal and oak lie around the town, where a wide variety of rare orchids are found. The Lloyd's Botanical Garden preserves common and rare species of plants, while the Padmaja Naidu Himalayan Zoological Park specialises in conserving and breeding endangered Himalayan species.[44] The town of Darjeeling and surrounding region face deforestation due to increasing demand for wood fuel and timber, as well as air pollution from increasing vehicular traffic.[45]

Forests and wildlife in the district are managed and protected by the Divisional Forest Officer of the Territorial and Wildlife wing of the West Bengal Forest Department.[42] The fauna found in Darjeeling includes several species of ducks, teals, plovers and gulls that pass Darjeeling while migrating to and from Tibet.[46] Small mammals found in the region include small Indian civets, mongooses and badgers.[47] TA conservation centre for red pandas opened at Darjeeling Zoo in 2014, building on a prior captive breeding program.[48]

Civic administration

The Darjeeling urban agglomeration consists of Darjeeling Municipality and the Tukvar Tea Garden (Tukvar valley).[49] Established in 1850, the Darjeeling municipality maintains the civic administration of the town, covering an area of 10.57 km2 (4.08 sq mi).[49] The municipality consists of a board of councillors elected from each of the 32 wards of Darjeeling town as well as a few members nominated by the state government. The board of councillors elects a chairman from among its elected members;[32] the chairman is the executive head of the municipality. The Gorkha Janmukti Morcha (GJMM) holds power in the municipality As of 2011.

From 1988 to 2012, the Gorkha-dominated hill areas of Darjeeling district were under the jurisdiction of the Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council (DGHC). In 2012, the DGHC was replaced by the Gorkhaland Territorial Administration (GTA). The elected members of this body are authorised to manage certain affairs of the hills, including education, health and tourism. Law and order in Darjeeling town comes under the jurisdiction of the district police force, which is a part of the West Bengal Police; a Deputy Superintendent of Police oversees the town's security and law affairs. Darjeeling municipality area has two police stations at Darjeeling and Jorebungalow.[50]

Civil utilities

Natural springs in the Senchal Range provide most of Darjeeling's water supply. Water collected is routed through stone conduits to two lakes that were constructed in 1910 and 1932, from where it is piped to the town after purification at the Jorebungalow filtration plant.[51] During the dry season, when water supplied by springs is insufficient, water is pumped from Khong Khola, a nearby small perennial stream. Increasing demand has led to a worsening shortfall in water supply; just over 50% of the town's households are connected to the municipal water supply system.[32] Various efforts made to augment the water supply, including the construction of a third storage reservoir in 1984, have failed to yield desired results.[51]

The town has an underground sewage system, covering about 40% of the town area, that collects domestic waste and conveys it to septic tanks for disposal.[52] Solid waste is disposed of in a nearby dumping ground, which also houses the town's crematorium.[52] Doorstep collection of garbage and segregation of biodegradable and non-biodegradable waste have been implemented since 2003.[53] Vermicomposting of vegetable waste is carried out with the help of non-governmental organisations.[54] In June 2009, in order to reduce waste, the municipality proposed a ban on plastic carrier bags and sachets in the town.[55]

Darjeeling got from 1897 up to the early 1990s hydroelectricity from the nearby Sidrapong Hydel Power Station, such being the first town in India supplied with hydropower. Today, electricity is supplied by the West Bengal State Electricity Board from other places. The town often suffers from power outages and the electrical supply voltage is unstable, making voltage stabilisers popular with many households. Almost all of the primary schools are now maintained by Darjeeling Gorkha Autonomous Hill Council. The total length of all types of roads within the municipal area is around 134 km (83 mi).[56] The West Bengal Fire Service provides emergency services for the town.

Economy

The two most significant contributors to Darjeeling's economy are tourism and the tea industry. Darjeeling tea, due to the unique agro-climatic conditions of Darjeeling, has a distinctive natural flavour, is internationally reputed and recognised as a geographical indicator. The office of the Darjeeling Indian Tea Association (DITA) is located at Darjeeling.[4] Darjeeling produces 7% of India's tea output, approximately 9,000,000 kilograms (20,000,000 lb) every year.[30] The tea industry has faced competition in recent years from tea produced in other parts of India as well as other countries like Nepal.[57] Widespread concerns about labour disputes, worker layoffs and closing of estates have affected investment and production.[58] Several tea estates are being run on a workers' cooperative model, while others are being planned for conversion into tourist resorts.[58] More than 60% of workers in the tea gardens are women.[49] Besides tea, the most widely cultivated crops include maize, millets, paddy, cardamom, potato and ginger.[59]

Darjeeling had become an important tourist destination as early as 1860.[17] It is reported to be the only location in eastern India that witnesses large numbers of foreign tourists.[30] It is also a popular filming destination for Bollywood and Bengali cinema. Satyajit Ray shot his film Kanchenjungha (1962) here, and his Feluda series story, Darjeeling Jomjomaat, was also set in the town. Bollywood movies such as Aradhana (1969), Main Hoon Na (2004), Parineeta (2005) and more recently Barfi! (2012) have been filmed here.[60][61]

Tourism

Tourist inflow into Darjeeling had been affected by the political instability in the region, and agitations in the 1980s and 2000s hit the tourism industry hard.[30][62] However, since 2012, Darjeeling has once again witnessed a steady inflow of both domestic and international tourists. Presently, around 50,000 foreign and 500,000 domestic tourists visit Darjeeling each year,[63] and its repute as the "Queen of the Hills" remains unaltered. According to an India Today survey published on 23 December 2015, Darjeeling is the third most Googled travel destination among all the tourist destinations in India. Even though there are political instabilities in Darjeeling, its tourism rate is increasing year by year. Many visit this place for food specialities like momos, steamed stick rice, and other steamed foods famous in this region, as well as to see the natural beauty of the area.[64]

Transport

Darjeeling can be reached by the 88 km (55 mi) long Darjeeling Himalayan Railway from New Jalpaiguri, or by National Highway 55, from Siliguri, 77 km (48 mi) away.[65][66] The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway is a 600 mm (2 ft) narrow-gauge railway that was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1999 for being "an outstanding example of the influence of an innovative transportation system on the social and economic development of a multi-cultural region, which was to serve as a model for similar developments in many parts of the world",[67] becoming only the second railway in the world to have this honour.[19][60] Bus services and hired vehicles connect Darjeeling with Siliguri and Darjeeling has road connections with Bagdogra, Gangtok and Kathmandu and the neighbouring towns of Kurseong and Kalimpong.[65] However, road and railway communications often get disrupted in the monsoons because of landslides. The nearest airport is Bagdogra Airport, located 90 km (56 mi) from Darjeeling.[65] Within the town, people usually traverse by walking. Residents also use two-wheelers and hired taxis for travelling short distances. The Darjeeling Ropeway, functional since 1968, was closed in 2003 after an accident killed four tourists.[68] It reopened in February 2012.[69]

Demographics

According to provisional results of 2011 census of India, Darjeeling urban agglomeration has a population of 132,016, out of which 65,839 were males and 66,177 were females. The sex ratio is 1,005 females per 1,000 males. The 0–6 years population is 7,382. Effective literacy rate for the population older than 6 years is 93.17 per cent.[70]

According to the 2001 census, the Darjeeling urban agglomeration, with an area of 12.77 km2 (4.93 sq mi), had a population of 109,163, while the municipal area had a population of 107,530.[49] The population density of the municipal area was 10,173 inhabitants per square kilometre (26,350/sq mi). The sex ratio was 1,017 females per 1,000 males,[49] which was higher than the national average of 933 females per 1000 males.[71] Gorkhas, speaking Nepali as native language, form the majority which includes indigenous ethnic groups such as the Bhutia, Chhetri, Gurung, Lepcha, Limbu, Magar, Newars, Rai, Sherpa, Tamang, Yolmo, along with several other denominations under the Indo-Aryan Khas and the Mongoloid Kirats. Other communities that inhabit Darjeeling include the Anglo-Indians, Bengalis, Biharis, Chinese, Marwaris, Rajbanshis and Tibetans. The prevailing languages are Nepali, Hindi, Bengali and English. Bengali is prevalent in the plains while Tibetan is used by the refugees and some tribal people.[5] Dzongkha is spoken by the Bhutias and the Tibetans.

Darjeeling has seen a significant growth in its population, its decadal growth rate being 47% between 1991 and 2001.[49] The colonial town was designed for a population of only 10,000, and subsequent growth has created extensive infrastructural and environmental problems. The district's forests and other natural wealth have been adversely affected by an ever-growing population. The official languages of Darjeeling are Bengali and Nepali.[3]

Religion

The predominant religions of Darjeeling are Shaivite Hinduism and Vajrayana Buddhism, followed by Christianity.[72] Indigenous communities such as the Lepchas, the Limbus, and many others, also practice Animism and Shamanism which is very often, but not always, intermixed with the more mainstream Hinduism and Buddhism.[73]

Dashain, Tihar, Losar, Buddha Jayanti, Christmas are the main festivals. Besides, the diverse ethnic populace of the town also celebrates several local festivals. Buddhist ethnic groups which include the Tibetans, Lepchas, Bhutias, Sherpas, Yolmos, Gurungs, and Tamangs celebrate their new year, called Losar, in January/February, Maghe Sankranti, Chotrul Duchen and Tendong Lho Rumfaat. The Kiranti Rai people (Khambus) celebrate their annual Sakela festivals of Ubhauli and Udhauli. Deusi and Bhaileni are songs performed by men and women respectively, during the festival of Tihar. All these provide a regional distinctness to Darjeeling's local culture from the rest of India. Darjeeling Carnival, initiated by a civil society movement known as The Darjeeling Initiative, is a ten-day carnival held yearly during the winter with portrayal of the Darjeeling Hill's musical and cultural heritage as its central theme.[74]

Culture

The culture of Darjeeling is diverse and includes a variety of indigenous practices and festivals as mentioned above. Many of the Nepali Hindus, as well as the various Buddhist and other ethnic groups such as the Lepchas, Bhutias, Kiranti Limbus, Tibetans, Yolmos, Gurungs, and Tamangs, have their own distinct languages and cultures and yet share a largely harmonious co-existence.

Colonial architecture characterizes many buildings in Darjeeling, exemplified by several mock Tudor residences, Gothic churches, the Raj Bhawan, Planters' Club and various educational institutions. Buddhist monasteries showcase the pagoda style architecture. Darjeeling is regarded as a centre of music and a niche for musicians and music admirers. Singing and playing musical instruments are common pastimes among the resident population, who take pride in the traditions and role of music in cultural life.[75] Darjeeling also has a Peace Pagoda built-in 1992 by the Japanese Buddhist organisation Nipponzan Myohoji.

Cuisine

Due to the varied mix of cultures in Darjeeling, the local and ethnic food of Darjeeling is also quite varied. Rice, noodles, and potatoes seem to make up the dominant part of the cuisine partly due to the cold climate. The most popular local snack food are Momos, which are steamed flour dumplings with meat or vegetables fillings served piping hot with a side of clear soup and hot homemade tomato sauce. Locals love Alu Dom (Spicy steamed potato curry) and various versions of it are served. For example, they add Wai Wai Mimi instant noodles over a bowl of Alu Dom and call it Alu Mimi.[76]

Another popular food is Thukpa which is of Tibetan origins. Thukpa is homemade noodle soup with meat, eggs and/or vegetables. Kinema, Chhurpi, Shaphalay, (Tibetan bread stuffed with meat).[77] Fermented foods and beverages are consumed by a large percentage of the population.[78] Fermented foods include preparations of soybean, bamboo shoots, milk and Sel roti, which is made from rice.[79] Tea (esp. the butter tea) is the most popular delicacy,[77] Alcoholic beverages include Tongba, Jnaard and Chhaang, variations of a local beer made from fermenting finger millet.[77][80][81]

A bowl of Alu Mimi

A bowl of Alu Mimi

Education

Having been a summer retreat for the British in India, Darjeeling became the place of choice for the establishment of public schools on the model of Eton, Harrow and Rugby, allowing the children of British officials to obtain an exclusive education.[82] Institutions such as Mount Hermon School, St. Robert's H.S. School, St. Paul's School, St. Joseph's School - North Point, Loreto Convent are renowned as centres of educational excellence.[83] There are 52 primary schools, 67 high schools and 5 colleges in the town.[52]

Darjeeling's schools are run either by the state government or by private or religious organisations. Schools mainly use English and Nepali as their media of instruction, although there is the option to learn the official language Hindi and the official state language Bengali. The schools are either affiliated with the ICSE, the CBSE, or the West Bengal Board of Secondary Education.

Darjeeling has five colleges—St. Joseph's College, Southfield College (earlier known as Loreto College), Darjeeling Government College, Ghoom-Jorebunglow Degree College and Sri Ramakrishna B.T. College—all affiliated to the University of North Bengal in Siliguri.

Political unrest

- See article Gorkhaland

See also

Notes

- "Pratibha Rai Takes Over As Chairperson Of Darjeeling Municipal Corporation". Siliguri Times. 17 January 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- "District Profile". Official webpage. Darjeeling district. Archived from the original on 17 August 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- "Report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India: 50th report (delivered to the Lokh Sabha in 2014)" (PDF). National Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities, Ministry of Minority Affairs, Government of India. p. 95. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- Srivastava 2003, p. 4024.

- "People And Culture". Official webpage of Darjeeling District. Archived from the original on 25 December 2008. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- Subba U.,( 'Sabdatitma Tajenglung' (Title) by Sankarhang Subba,) (Editor) Yuma Manghim Udghatan Samaroha Smarika 2017, Nalichour, Sonada, published by Limbu/ Subba Tribal Society, Darjeeling.

- "Pre-Independence [Darjeeling]". Government of Darjeeling. Archived from the original on 31 October 2015. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- Dasgupta 1999, pp. 47–48.

- Dasgupta 1999, p. 51.

- Pradhan R.M., compiled, Continuous Political Struggle for a separate Constitutionl status of Ceded Land of Darjeeling and Leasehold land of Kalimpong, Published by Department of Information & Cultural Affairs,DGHS.(1996). page 1/2

- Dozey, E. C. (1922). 1922 Darjeeling Past and Present – A Concise History of Darjeeling District since 1835. University of Michigan Library. p. 2. ASIN B00416COE4.

- "History of Darjeeling". Official webpage. Darjeeling district. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- Dasgupta 1999, p. 50.

- Lamb 1986, p. 69.

- Dasgupta 1999, p. 47.

- Dasgupta 1999, p. 48.

- Lamb 1986, p. 71.

- Kenny 1995, p. 700.

- "Mountain Railways of India". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. UNESCO. Archived from the original on 3 May 2006. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- Gerard 1990, p. 258.

- Borbara, Sanjoy (2003). "Autonomy for Darjeeling: History and Practice". Experiences on Autonomy in East and North East: A Report on the Third Civil Society Dialogue on Human Rights and Peace. Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- Dasgupta 1999, p. 60.

- "Darjeeling Hills plunges into the Independence Movement". Official webpage. Darjeeling district. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- Dasgupta 1999, p. 61.

- Dasgupta 1999, p. 55.

- Dasgupta 1999, pp. 61–62.

- Dasgupta 1999, p. 62.

- Dasgupta 1999, pp. 63–64.

- Dasgupta 1999, p. 65.

- Dhar, S. (2009). "Darjeeling protests hit tea and tourism". Livemint. Archived from the original on 8 December 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- "Darjeeling tripartite pact signed for Gorkhaland Territorial Administration". Times of India. 18 July 2011. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- Khawas, Vimal (2003). "Urban Management in Darjeeling Himalaya: A Case Study of Darjeeling Municipality". The Mountain Forum. Archived from the original on 20 October 2004. Retrieved 1 May 2006.

- "Darjeeling". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service. Retrieved 26 July 2006.

- "Station: Darjeeling Climatological Table 1981–2010" (PDF). Climatological Normals 1981–2010. India Meteorological Department. January 2015. pp. 227–228. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- "Extremes of Temperature & Rainfall for Indian Stations (Up to 2012)" (PDF). India Meteorological Department. December 2016. p. M233. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- "Klimatafel von Darjeeling, West Bengal / Indische Union" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- "Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". Climate-Data.org. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- Malley, L.S.S. O (1999) [1907]. Bengal District Gazetteer : Darjeeling. Concept Publishing Company. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-81-7268-018-3. Archived from the original on 9 May 2016.

- Sarkar 1999, p. 299.

- Malabi Gupta (26 November 2009). "Brewtal climate: Droughts, storms cracking Darjeeling's teacup". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- "Darjeeling Weather & Best Time to Visit". Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- Negi 1992, p. 185.

- Negi 1992, pp. 28–29.

- "Himalayan Tahrs, Blue sheep for Darjeeling Zoo arrive from Japan". The Hindu. 29 October 2009. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- TERI (2001). "Sustainable Development in the Darjeeling Hill Area" (PDF). Tata Energy Research Institute, New Delhi. (TERI Project No.2000UT64). p. 20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 June 2006. Retrieved 1 May 2006.

- Mackintosh 2009, p. 2.

- Negi 1992, pp. 43–48.

- "Snow leopard, red panda get new conservation centre in Darjeeling". The Indian Express. 27 June 2014. Archived from the original on 22 November 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- "Table-4 Population, Decadal Growth Rate, Density and General Sex Ratio by Residence and Sex, West Bengal/ District/ Sub District, 1991 and 2001". Directorate of Census Operations, West Bengal. 2003. Archived from the original on 27 August 2005. Retrieved 30 April 2006.

- "Table-3 District Wise List of Statutory Towns (Municipal Corporation, Municipality, Notified Area and Cantonment Board), Census Towns and Outgrowths, West Bengal, 2001". Directorate of Census Operations, West Bengal. 2003. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2006.

- "Water Supply". Official webpage. Darjeeling municipality. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2009.

- "General Information". Official webpage. Darjeeling municipality. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- Aftab 2005, p. 186.

- Aftab 2005, p. 187.

- Dam, Mohana (11 June 2009). "Darjeeling to ban plastic altogether". Express India. The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- "Roads". Official webpage. Darjeeling municipality. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- "Darjeeling tea growers at risk". BBC News. 27 July 2001. Archived from the original on 27 March 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- Haber, Daniel B. (14 January 2004). "Economy-India: Famed Darjeeling Tea Growers Eye Tourism for Survival". Inter Press Service News Agency. Archived from the original on 2 June 2006. Retrieved 8 May 2006.

- "Agriculture". Official webpage. Darjeeling district. Archived from the original on 29 January 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- Sudha Mahalingam (March 2001). "Darjeeling: Where the journey is the destination". Outlook Traveller. Outlook Publishing (India) Private Limited. Archived from the original on 15 April 2007. Retrieved 9 March 2007.

- "Darjeeling Toy Train". Theme India: Train Tourism in India. IndiaLine. Archived from the original on 7 May 2010. Retrieved 5 December 2009.

- Dasgupta 1999, p. 66.

- "Darjeeling hills showing highly positive tourist inflow picture". timesofindia-economictimes. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- "Top 10 Indian destinations searched on Google in 2015 : Plus List, News - India Today". indiatoday.intoday.in. Archived from the original on 31 December 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- de Bruyn et al. 2008, p. 578.

- "NH wise Details of NH in respect of Stretches entrusted to NHAI" (PDF). National Highways Authority of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- "World Heritage Committee: Report of the 23rd Session, Marrakesh, 1999". UNESCO. 1999. Darjeeling Himalayan Railway. Archived from the original on 24 June 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- "Darjeeling ropeway mishap kills four". The Statesman. 20 October 2003. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 30 June 2007.

- Banerjee, Amitava (2 February 2012). "Darjeeling ropeway reopens after more than 8 yrs". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- "Urban agglomerations/cities having population 1 lakh and above" (PDF). Provisional population totals, census of India 2011. The registrar general & census commissioner, India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- "India at a Glance: Sex Ratio". Census of India, 2001. Archived from the original on 13 November 2009. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- "Darjiling District Religion Data - Census 2011". Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- "Basic data sheet, District Darjiling" (PDF). Census of India, 2001. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- S.S. Chattopadhyay (December 2003). "The spirit of Darjeeling". Frontline. 20 (25). Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 1 May 2006.

- D. P. Rasaily; R. P. Lama. "The Nature-centric Culture of the Nepalese". The Cultural Dimension of Ecology. Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, New Delhi. Archived from the original on 15 July 2006. Retrieved 31 July 2006.

- Baral, Bipin (2015). And... The Crossroad. Partridge Publishing. ISBN 9781482849868.

- "People & Culture". Official webpage. Darjeeling district. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- Tamang, Sarkar & Hesseltine 1988, p. 376.

- Tamang, Sarkar & Hesseltine 1988, p. 375.

- Tamang, Sarkar & Hesseltine 1988, p. 382.

- H. Ä. Jaschke (1881). A Tibetan-English Dictionary (1987 reprint ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas. p. 341. ISBN 978-81-208-0321-3.

- Lal, V. "Hill Stations: Pinnacles of the Raj". = UCLA Social Sciences Computing. Archived from the original on 22 June 2001.

- "Educational Institutes". Official webpage. Darjeeling district. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

References

- Aftab, Aaris (2005). Are the Third World cities sustainable?. Allied Publishers. p. 201. ISBN 978-81-7764-869-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dasgupta, Atis (1999). "Ethnic Problems and Movements for Autonomy in Darjeeling". Social Scientist. Social Scientist. 27 (11–12): 47–68. doi:10.2307/3518047. JSTOR 3518047.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- de Bruyn, Pippa; Bain, Keith; Venkatraman, Nilofer; Joshi, Shonar (2008). Frommer's India. Frommer's. ISBN 978-0-470-16908-7. Retrieved 8 January 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gerard, John (1990). Mountain environments: an examination of the physical geography of mountains. MIT Press. p. 317. ISBN 978-0-262-07128-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kenny, Judith (1995). "Climate, Race, and Imperial Authority: The Symbolic Landscape of the British Hill Station in India". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. [Association of American Geographers, Taylor & Francis, Ltd.] 85 (4): 694–714. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1995.tb01821.x. JSTOR 2564433.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lamb, Alastair (1986). British India and Tibet, 1766–1910 (2nd ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 353. ISBN 978-0-7102-0872-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mackintosh, L.J. (2009). Birds of Darjeeling and India (2nd ed.). BiblioBazaar, LLC. p. 322. ISBN 978-1-116-11396-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Negi, Sharad Singh (1992). Himalayan wildlife, habitat and conservation. Indus Publishing. p. 207. ISBN 978-81-85182-68-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sarkar, S. (1999). "Landslides in Darjeeling Himalayas, India". Transactions of the Japanese Geomorphological Union. 20 (3). pp. 299–315. ISSN 0389-1755.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Srivastava, Suresh C. (2003). "Geographical Indications and Legal Framework in India". Economic and Political Weekly. Economic and Political Weekly. 38 (38): 4022–4033. JSTOR 4414050.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tamang, Jyoti P.; Sarkar, Prabir K; Hesseltine, Clifford W (1988). "Traditional Fermented Foods and Beverages of Darjeeling" (PDF). Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 44 (4): 375–385. doi:10.1002/jsfa.2740440410. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Bradnock, R; Bradnock, R (2004). Footprint India Handbook (13th ed.). Footprint Handbooks. ISBN 978-1-904777-00-7.

- Brown, Percy (1917). Tours in Sikhim and the Darjeeling District (3rd (1934) ed.). Calcutta: W. Newman & Co. p. 223. ASIN B0008B2MIY.

- Forbes, Andrew ; Henley, David (2011). China's Ancient Tea Horse Road. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B005DQV7Q2

- Kennedy, Dane (1996). Magic Mountains: Hill Stations and the British Raj. University of California Press. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-520-20188-0.

- Lee, Ada (1971). The Darjeeling disaster: Triumph through sorrow: the triumph of the six Lee children. Lee Memorial Mission. ASIN B0007AUX00.

- Newman's Guide to Darjeeling and Its Surroundings, Historical & Descriptive, with Some Account of the Manners and Customs of the Neighbouring Hill Tribes, and a Chapter on Thibet and the Thibetans. W. Newman and Co. 1900.

- Ronaldshay, The Earl of (1923). Lands of the Thunderbolt. Sikhim, Chumbi & Bhutan. London: Constable & Co. ISBN 81-206-1504-2.

- Roy, Barun (2003). Fallen Cicada - Unwritten History of Darjeeling Hills (2003 ed.). Beacon Publication. p. 223. ISBN 978-81-223-0684-2.

- Saraswati, Baidyanath (ed.) (1998). Cultural Dimension of Ecology. DK Print World Pvt. Ltd, India. ISBN 978-81-246-0102-0.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Singh, S. (2006). Lonely Planet India (11th ed.). Lonely Planet Publications. ISBN 978-1-74059-694-7.

- Waddell, L.A. (2004). Among the Himalayas. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7661-8918-8.

External links

- Darjeeling at Curlie