Sher Shah Suri

Sher Shah Suri (1486 – 22 May 1545), born Farīd Khān, was the founder of the Suri Empire in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, with its capital in Sasaram in modern-day Bihar. He introduced the currency of rupee.[2] An ethnic Pashtun, Sher Shah took control of the Mughal Empire in 1538. After his accidental death in 1545, his son Islam Shah became his successor.[3][4][5][6][7][8] He first served as a private before rising to become a commander in the Mughal army under Babur and then the governor of Bihar. In 1537, when Babur's son Humayun was elsewhere on an expedition, Sher Shah overran the state of Bengal and established the Suri dynasty.[9] A brilliant strategist, Sher Shah proved himself as a gifted administrator as well as a capable general. His reorganization of the empire laid the foundations for the later Mughal emperors, notably Akbar, son of Humayun.[9]

| Sher Shah Suri | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Padishah | |||||

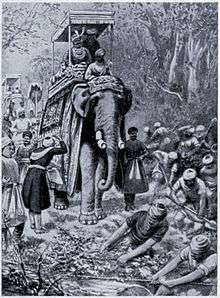

Imaginary sketch work of Sher Shah Suri by Afghan artist Abdul Ghafoor Breshna | |||||

| Sultan of the Suri Empire | |||||

| Reign | 17 May 1538 – 22 May 1545 | ||||

| Coronation | 1540 | ||||

| Predecessor | Humayun (as Mughal Emperor) | ||||

| Successor | Islam Shah Suri | ||||

| Born | 1486 Sasaram, Delhi Sultanate (now in Bihar, India[1] | ||||

| Died | 22 May 1545 (aged 58–59) Kalinjar, Sur Empire | ||||

| Burial | Sher Shah Suri Tomb, Sasaram | ||||

| Spouse | Utmadun nissa Bano Begum, Rani Shah Begum | ||||

| Issue | Islam Shah Suri (Jalal Khan) Adil Khan | ||||

| |||||

| House | House of Sur | ||||

| Dynasty | Sur Dynasty | ||||

| Father | Hassan Khan Sur | ||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||

During his seven-year rule from 1538 to 1545, he set up a new economic and military administration, issued the first Rupiya from "Taka" and organized the postal system of the Indian Subcontinent.[10] Some of his strategies and contributions were later ideolized by the Mughal emperors, most notably Akbar. Suri further developed Humayun's Dina-panah city and named it Shergarh and revived the historical city of Pataliputra, which had been in decline since the 7th century CE, as Patna.[11] He extended the Grand Trunk Road from Chittagong in the frontiers of the province of Bengal in northeast India to Kabul in Afghanistan in the far northwest of the country. The influence of his innovations and reforms extended far beyond his brief reign; his arch foe, Humayun, referred to him as “Ustad-I-Badshahan”, teacher of kings.

Early life and origin

Sher Shah Suri was born in Sasaram, a city in the state of Bihar in present-day India into a Pashtun family.[12][13] His surname 'Suri' was taken from his Pashtun Sur tribe. The name Sher (means lion or tiger in the older pronunciation of Persian) was conferred upon him for his courage, when as a young man, he killed a tiger that leapt suddenly upon the king of Bihar.[8][14] His grandfather Ibrahim Khan Suri was a landlord (Jagirdar) in Narnaul area and represented Delhi rulers of that period. Mazar of Ibrahim Khan Suri still stands as a monument in Narnaul. Tarikh-i Khan Jahan Lodi (MS. p. 151).[1] also confirm this fact. However, the online Encyclopædia Britannica states that he was born in Sasaram (Bihar), in the Rohtas district.[3] He was one of about eight sons of Mian Hassan Khan Suri, a prominent figure in the government of Bahlul Khan Lodi in Narnaul Pargana. His grandfather, Ibrahim Khan Suri, was a noble adventurer from Roh[15]; he was recruited much earlier by Sultan Bahlul Lodi of Delhi during his long contest with the Jaunpur Sultanate.

It was at the time of this bounty of Sultán Bahlol, that the grandfather of Sher Sháh, by name Ibráhím Khán Súri,*[The Súr represent themselves as descendants of Muhammad Súri, one of the princes of the house of the Ghorian, who left his native country, and married a daughter of one of the Afghán chiefs of Roh.] with his son Hasan Khán, the father of Sher Sháh, came to Hindu-stán from Afghánistán, from a place which is called in the Afghán tongue "Shargarí,"* but in the Multán tongue "Rohrí." It is a ridge, a spur of the Sulaimán Mountains, about six or seven kos in length, situated on the banks of the Gumal. They entered into the service of Muhabbat Khán Súr, Dáúd Sáhú-khail, to whom Sultán Bahlol had given in jágír the parganas of Hariána and Bahkála, etc., in the Panjáb, and they settled in the pargana of Bajwára.[1]

— Abbas Khan Sarwani, 1580

During his early age, Farid was given a village in Fargana, Delhi (comprising present day districts of Bhojpur, Buxar, Bhabhua of Bihar) by Omar Khan Sarwani, an ethnic Pashtun himself, the counselor and courtier of Bahlul Khan Lodi. Farid Khan and his father, a jagirdar of Sasaram in Bihar, who had several wives, did not get along for a while so he decided to run away from home. When his father discovered that he fled to serve Jamal Khan, the governor of Jaunpur, Uttar Pradesh, he wrote Jamal Khan a letter that stated:

Faríd Khán, being annoyed with me, has gone to you without sufficient cause. I trust in your kindness to appease him, and send him back; but if refusing to listen to you, he will not return, I trust you will keep him with you, for I wish him to be instructed in religious and polite learning.[16]

Jamal Khan had advised Farid to return home but he refused. Farid replied in a letter:

If my father wants me back to instruct me in learning, there are in this city many learned men: I will study here.[16]

Conquest of Bihar and Bengal

Mirza Aziz Koka, son of Ataga Khan, in a letter to Emperor Jahangir

Farid Khan started his service under Bahar Khan Lohani, the Mughal Governor of Bihar.[3][17] Because of his valour, Bahar Khan rewarded him the title Sher Khan (Lion Lord). After the death of Bahar Khan, Sher Khan became the regent ruler of the minor Sultan, Jalal Khan. Later sensing the growth of Sher Shah's power in Bihar, Jalal sought the assistance of Ghiyasuddin Mahmud Shah, the independent Sultan of Bengal. Ghiyasuddin sent an army under General Ibrahim Khan. But, Sher Khan defeated the force at the battle of Surajgarh in 1534 after forming an alliance with Ujjainiya Rajputs and other local chiefdoms.[18] Thus he achieved complete control of Bihar.[17]

In 1538, Sher Khan attacked Bengal and defeated Mahmud Shah.[17] But he could not capture the kingdom because of the sudden expedition of Emperor Humayun.[17] On 26 June 1539, Sher Khan faced Humayun in the Battle of Chausa and defeated him. Assuming the title Farīd al-Dīn Shēr Shah, he defeated Humayun once again at Kannauj in May 1540 and forced him out of India.[3][19]

Conquest of Malwa

After the death of Bahadur Shah of Gujarat in 1537, Qadir Shah became the new ruler of Malwa Sultanate. He then turned for support towards the Rajput and Muslim noblemen of the Khilji rule of Malwa. Bhupat Rai and Puran Mal, sons of Raja Silhadi accepted service under the regime of Malwa in recognition of their interest in the Raisen region. By 1540, Bhupat Rai had died and Puran Mal had become the dominant force in eastern Malwa. In 1542, Sher Shah conquered Malwa without a fight and Qadir Shah fled to Gujarat. He then appointed Shuja'at Khan as the governor of Malwa who reorganised the administration and made Sarangpur the seat of Malwa's government. Sher Shah then ordered Puran Mal to be brought before him. Puran Mal agreed to accept his lordship and left his brother Chaturbhuj under Sher Shah's service. In exchange Sher Shah vowed to safeguard Puran Mal and his land.[20][21]

The Muslim women of Chanderi, which Sher Shah had taken under his rule, came to him and accused Puran Mal of killing their husbands and enslaving their daughters. They threatened to denounce Sher Shah on the Day of Resurrection if he did not avenge them. Upon reminding them of his pledge to safeguard Puran Mal, they told him to consult his ulema. The ulema issued a fatwa declaring that Puran Mal deserved death. Sher Shah had his troops encircle Puran Mal's camp. Upon seeing this, Puran Mal beheaded his wife and ordered the other Rajputs to kill their families too. Nizamuddin Ahmad writes that 4,000 Rajputs of importance were there. `Abd al-Qadir Bada'uni puts the number of Rajputs at 10,000.[22]

Historian Abbas Sarwani describes the scene thus, "While the Hindus were employed in putting their women and families to death, the Afghans on all sides commenced the slaughter of the Hindus. Puran Mal and his companions... failed not to exhibit valour and gallantry, but in the twinkling of an eye all were slain." Only a few women and children survived. Puran Mal's daughter was given to minstrels to be a dancing girl while his three nephews were castrated. As an excuse for the treachery, Sher Shah claimed it as a revenge for enslavement of Muslim women and that he had once, when seriously ill, pledged to wipe out the Rajputs of Raisen.[23]

Conquest of Marwar

In 1543, Sher Shah Suri with a huge force of 80,000 cavalry set out against Maldeo Rathore (a Rajput king of Marwar). Maldeo Rathore with an army of 50,000 cavalry advanced to face Sher Shah's army. Instead of marching to the enemy's capital Sher Shah halted in the village of Sammel in the pargana of Jaitaran, ninety kilometres east of Jodhpur. After one month of skirmishing, Sher Shah's position became critical owing to the difficulties of food supplies for his huge army. To resolve this situation, Sher Shah resorted to a cunning ploy. One evening, he dropped forged letters near the Maldeo's camp in such a way that they were sure to be intercepted. These letters indicated, falsely, that some of Maldeo's army commanders were promising assistance to Sher Shah. This caused great consternation to Maldeo, who immediately (and wrongly) suspected his commanders of disloyalty. Maldeo left for Jodhpur with his own men, abandoning his commanders to their fate.[24]

After that Maldeo's innocent generals Jaita and Kumpa fought with just a few thousand men against an enemy force of 80,000 men and cannons. In the ensuing battle of Sammel (also known as battle of Giri Sumel), Sher Shah emerged victorious, but several of his generals lost their lives and his army suffered heavy losses. Sher Shah is said to have commented that "for a few grains of bajra (millet, which is the main crop of barren Marwar) I almost lost the entire kingdom of Hindustan."[25]

After this victory, Sher Shah's general Khawas Khan Marwat took possession of Jodhpur and occupied the territory of Marwar from Ajmer to Mount Abu in 1544.[24]

Government and administration

The system of tri-metalism which came to characterise Mughal coinage was introduced by Sher Shah. While the term rūpya had previously been used as a generic term for any silver coin, during his rule the term rūpee came to be used as the name for a silver coin of a standard weight of 178 grains, which was the precursor of the modern rupee.[10] Rupee is today used as the national currency in India, Indonesia, Maldives, Mauritius, Nepal, Pakistan, Seychelles, Sri Lanka among other countries. Gold coins called the Mohur weighing 169 grains and copper coins called Paisa were also minted by his government.[10] According to numismatists Goron and Goenka, it is clear from coins dated AH 945 (1538 AD) that Sher Khan had assumed the royal title of Farid al-Din Sher Shah and had coins struck in his own name even before the battle of Chausa.[26]

Sher Shah was responsible for greatly rebuilding and modernizing the Grand Trunk Road, a major artery which runs all the way from modern day Bangladesh to Afghanistan, and which was referred to as Shah Rah e Azam (Urdu: شاہراہ اعظم or The Great Road) in his time. Caravanserais (inns), temples and mosques were built and trees were planted along the entire stretch on both sides of the road to provide shade to travelers. Wells were also dug, especially along the western section. He also established an efficient postal system, with mail being carried by relays of horse riders.

Sher Shah built several monuments including Rohtas Fort (now a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Pakistan), many structures in the Rohtasgarh Fort in Bihar, the Sher Shah Suri Masjid in Patna, the Qila-i-Kuhna mosque inside the Purana Qila complex in Delhi, and the Sher Mandal, an octagonal building also inside the Purana Qila complex, which later served as the library of Humayun. He built a new city, Bhera, in present day Pakistan in 1545, including within it a grand masjid named after him.

Sher Shah is generally viewed as tolerant of Hindus, except in the massacre following the surrender of Raisen.[3]

Tarikh-i-Sher Shahi (History of Sher Shah), written by Abbas Khan Sarwani, a waqia-navis under later Mughal Emperor, Akbar around 1580, provides a detailed documentation about Sher Shah's administration.

Religious persecution

In 1545, Sher Shah Suri led a campaign of religious violence across western and eastern provinces of the Empire in India. As with theologians and court officials of Delhi Sultanate, his advisors counseled in favor of religious violence. Shaikh Nizam, for example, counseled, "There is nothing equal to a religious war against the infidels. If you be slain you become a martyr, if you live you become a ghazi."[27] Sher Shah's Mughal army then attacked the Hindu fort of Kalinjar, captured it, killing every Hindu inside that fort.[27]

Death and succession

.jpg)

Sher Shah was killed on 22 May 1545 during the siege of Kalinjar fort in Bundelkhand against the Rajputs of Mahoba.[3] When all tactics to subdue this fort failed, Sher Shah ordered the walls of the fort to be blown up with gunpowder, but he himself was seriously wounded as a result of the explosion of a mine. He was succeeded by his son, Jalal Khan, who took the title of Islam Shah Suri. His mausoleum, the Sher Shah Suri Tomb (122 ft high), stands in the middle of an artificial lake at Sasaram, a town on the Grand Trunk Road.[28]

Legacy

Destruction of cities

Sher Shah Suri is accused by `Abd al-Qadir Bada'uni and other Muslim historians for destroying old cities while founding new ones on their ruins after his own name.[29][30] Shergarh is one of the prime examples, representing a deserted town with a fort in ruins, which, in old times, used to be a thriving place where Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism co-existed peacefully. This can be evidently derived from the various inscriptions found in the area.[31] Sher Shah is also said to have destroyed Dinpanah, which Humayun was constructing as the "sixth city of Delhi". The new city, Shergarh, built by him, was itself destroyed in 1555 after Humayun re-conquered the territory from the Surs.[32] Tarikh-i-Da'udi states, however, that he destroyed Siri. Abbas Sarwani states that he had the older city of Delhi destroyed. Tarikh-i-Khan Jahan states that Salim Shah Suri had built a wall around Humayun's imperial city.[33]

Gallery

Lal Darwaza, the southern gate of Shergarh

Lal Darwaza, the southern gate of Shergarh Rohtas Fort's Kabuli Gate

Rohtas Fort's Kabuli Gate Qila-i-Kuhna mosque, built by Sher Shah in 1541

Qila-i-Kuhna mosque, built by Sher Shah in 1541 Sher Mandal built in his honour by the Mughals

Sher Mandal built in his honour by the Mughals Copper Dam issued from Narnul mint

Copper Dam issued from Narnul mint

See also

References

- Abbas Khan Sarwani (1580). "Táríkh-i Sher Sháhí; or, Tuhfat-i Akbar Sháhí, of 'Abbás Khán Sarwání. CHAPTER I. Account of the reign of Sher Sháh Súr". Sir H. M. Elliot. London: Packard Humanities Institute. p. 78. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- "Mughal Coinage". Archived from the original on 5 October 2002.

Sher Shah issued a coin of silver which was termed the Rupiya. This weighed 178 grains and was the precursor of the modern rupee. It remained largely unchanged till the early 20th Century

- "Shēr Shah of Sūr". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (2002). History of medieval India: from 1000 A.D. to 1707 A.D. Crabtree Publishing Company. p. 179. ISBN 978-81-269-0123-4. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- Schimmel, Annemarie; Burzine K. Waghmar (2004). The empire of the great Mughals: history, art and culture. Reaktion Books. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-86189-185-3. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- Singh, Sarina; Lindsay Brown; Paul Clammer; Rodney Cocks; John Mock (2008). Pakistan & the Karakoram Highway (7th ed.). Lonely Planet. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-74104-542-0. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- Greenberger, Robert (2003). A Historical Atlas of Pakistan. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-8239-3866-7. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- Lane-Poole, Stanley (2007) [First published 1903]. Medieval India: under Mohammedan rule (A.D. 712-1764). Sang-e-Meel Publications. p. 236. ISBN 978-969-35-2052-1.

- "Sher Khan". Columbia Encyclopedia. 2010. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- "Mughal Coinage". RBI Monetary Museum. Reserve Bank of India. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- Patna encyclopedia.com.

- Asad Muḥammad K̲h̲ān̲, The Harvest of Anger and Other Stories, Oxford University Press (2002), p. 62

- Ishwari Prasad, The Mughal Empire, Chugh Publications (1974), p. 157

- "Sur Dynasty". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- "Ancestral village in medieval Afghanistan". barmazid.com.

- Abbas Khan Sarwani (1580). "Táríkh-i Sher Sháhí; or, Tuhfat-i Akbar Sháhí, of 'Abbás Khán Sarwání. CHAPTER I. Account of the reign of Sher Sháh Súr". Sir H. M. Elliot. London: Packard Humanities Institute. p. 79. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- Ali, Muhammad Ansar (2012). "Sher Shah". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Ahmad, Imtiaz (2008). "State Formation and Consolidation under the Ujjaniya Rajputs". In Surinder Singh; Ishawr Dayal Gaur (eds.). Popular Literature and Pre-modern Societies in South Asia. Pearson Education India. p. 80. ISBN 978-81-317-1358-7.

- Haig, Wolseley (1962) [First published 1937]. "Sher Shah and the Sur Dynasty". In Burn, Richard (ed.). The Cambridge History of India. Volume IV: The Mughal Period. Cambridge University Press. p. 51. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- Kolff, Dirk H. A. (2002) [First published 1990]. Naukar, Rajput, and Sepoy: The Ethnohistory of the Military Labour Market of Hindustan, 1450-1850. Cambridge University Press. p. 104. ISBN 9780521523059.

- Middleton, John (2015). World Monarchies and Dynasties. Routledge. p. 568. ISBN 9781317451587.

- Kolff, Dirk H. A. (2002) [First published 1990]. Naukar, Rajput, and Sepoy: The Ethnohistory of the Military Labour Market of Hindustan, 1450-1850. Cambridge University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-521-52305-9.

- Eraly, Abraham (2002) [First published 1997]. Emperors of the Peacock Throne: The Saga of the Great Mughals. Penguin Books India. pp. 91–92. ISBN 978-0-14-100143-2.

- Majumdar, R. C., ed. (2006) [First published 1974]. The History and Culture of the Indian People. Volume 7: The Mughal Empire. Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. pp. 81–82. OCLC 3012164.

- Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals Part - II By Satish Chandra pg.80. — Sher Shahs oft quoted remark " I had given away the country of Delhi for a handful of millets" is a tribute to the gallantry of Jaita and Kumpa and the willingness of the Rajputs to face death even in the face of impossible odds.

- Goron, Stan; Goenka, J. P. (2001). The Coins of the Indian Sultanates. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. p. 98. ISBN 978-81-215-1010-3.

This and the next items show Sher Shāh to have adopted the royal title as early as year 945 ... within circle: al-sultān sher shāh ... In margin: farīd al-dunyā wa 'l dīn abū'l muzaffar khallada allāh mulkahu

- Elliot and Dowson, The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians - The Muhammadan Period, Vol. 4, Trubner & Co., London, pp. 408–409

- Asher, Catherine B. (1977). "The Mausoleum of Sher Shāh Sūrī". Artibus Asiae. 39 (3/4): 273–298. doi:10.2307/3250169. JSTOR 3250169.

- `Abd al-Qadir Bada'uni (1898). Muntakhab-ut-Tawarikh (English translation (Bib. Ind.) ed.). Calcutta. p. 472.

- Qanungo, K. R. (1921). Sher Shah. p. 404.

- "Jain inscription from Shergarh (Dr. D.C. Sircar)". South Indian Inscriptions. Manager of Publications, Delhi.

- Bolande-Crew, Tara; Lea, David. "The Territories and States of India".

- D'Ayala, Diana. Structural Analysis of Historic Construction: Preserving Safety and Significance. pp. 290, 291.

Further reading

- Tarikh-i-Sher Shahi

- Tarikh-i Khan Jahani wa Makhzan-i Afghani

- Edward Thomas (1871) The Chronicles of the Pathan Kings of Delhi

- Sir Olaf Caroe, The Pathans

- Burgess, James (1913). The Chronology of Modern India for Four Hundred Years from the Close of the Fifteenth Century, AD. 1494–1894. John Grant, Edinburgh.

- "Sher Shah Suri; A Fresh Perspective"; Bashir Ahmad Khan Matta (Oxford University Press, Karachi, Pakistan) 2006