Bengal Presidency

The Bengal Presidency, officially the Presidency of Fort William and later Bengal Province, was a subdivision of the British Empire in India. At the height of its territorial jurisdiction, it covered large parts of what is now South Asia and Southeast Asia. Bengal proper covered the ethno-linguistic region of Bengal (present-day Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal). Calcutta, the city which grew around Fort William, was the capital of the Bengal Presidency. For many years, the Governor of Bengal was concurrently the Viceroy of India and Calcutta was the de facto capital of India until the early 20th-century.

Presidency of Fort William Bengal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1612–1947 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)  Left: Flag of the East India Company (1612-1858) Right: Union Jack (1858-1947) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Map showing the Bengal Presidency's jurisdiction in the 1860s | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Presidencies and provinces of British India | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Calcutta | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | English (official) Bengali, Hindustani | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Legislature of Bengal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bengal Legislative Council (1862-1947) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bengal Legislative Assembly (1935-1947) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Colonial era | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1612 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1947 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Indian rupee, Pound sterling | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Bengal Presidency emerged from trading posts established in Mughal Bengal during the reign of Emperor Jahangir in 1612. The Honourable East India Company (HEIC), a British monopoly with a Royal Charter, competed with other European companies to gain influence in Bengal. After the decisive overthrow of the Nawab of Bengal in 1757 and the Battle of Buxar in 1765, the HEIC expanded its control over much of the Indian subcontinent. This marked the beginning of Company rule in India, when the HEIC emerged as the most powerful military force in the subcontinent. The British Parliament gradually withdrew the monopoly of the HEIC. By the 1850s, the HEIC struggled with finances.[1] After the Indian Mutiny of 1857, the British government assumed direct administration of India. The Bengal Presidency was re-organized. In the early 20th-century, Bengal emerged as a hotbed of the Indian independence movement, as well as the epicenter of the Bengali Renaissance.

Bengal was the economic, cultural and educational hub of the British Raj. During the period of proto-industrialization, Bengal significantly contributed directly to the Industrial revolution in Britain, although it was soon overtaken by the Kingdom of Mysore ruled by Tipu Sultan as South Asia's dominant economic power.[2] When Bengal was reorganized, Penang, Singapore and Malacca were separated into the Straits Settlements in 1867.[3] British Burma became a province of India and a later a Crown Colony in itself. Western areas, including the Ceded and Conquered Provinces and The Punjab, were further reorganized. Northeastern areas became Colonial Assam. The Partition of British India in 1947 resulted in Bengal's division on religious grounds.

History

Background

In 1599, a Royal Charter was granted by Queen Elizabeth I to allow the creation of a trading company in London for the purposes of trade with the East Indies. The governance of the company was placed in the hands of a governor and a 24-member Court of Directors. The corporation became known as the Honourable East India Company (HEIC). It rose to account for half of the world's trade. The company was given a monopoly for British trade in the Indian Ocean.[1]

In 1608, Mughal Emperor Jahangir allowed the English East India Company to establish a small trading post on the west coast of India. It was followed in 1611 by a factory on the Coromandel Coast in South India, and in 1612 the company joined other already established European trading companies to trade in the wealthy Bengal Subah in the east.[4] However, the power of the Mughal Empire declined from 1707, as the Nawab of Bengal in Murshidabad became financially independent with the help of bankers such as the Jagat Seth. The Nawabs began entering into treaties with numerous European companies, including the French East India Company, the Dutch East India Company, and the Danish East India Company. The Mughal court in Delhi was weakened by Nader Shah's invasion from Persia (1739) and Ahmed Shah Durrani's invasion from Afghanistan (1761). The East India Company's victories at the Battle of Plassey (against the last independent Nawab of Bengal in 1757) and the Battle of Buxar (against the Nawabs of Bengal and Oudh in 1764) led to the abolition of local rule (Nizamat) in Bengal in 1793. The Company gradually began to formally expand its territories across India and Southeast Asia.[5] By the mid-19th century, the East India Company had become the paramount political and military power in the Indian subcontinent. Its territory was held in trust for the British Crown.[6] The Company also issued coins in the name of the nominal Mughal Emperor (who was exiled in 1857).

Administrative changes and the Permanent Settlement

Under Warren Hastings, the consolidation of British imperial rule over Bengal was solidified, with the conversion of a trade area into an occupied territory under a military-civil government, while the formation of a regularised system of legislation was brought in under John Shore. Acting through Lord Cornwallis, then Governor-General, he ascertained and defined the rights of the landholders over the soil. These landholders under the previous system had started, for the most part, as collectors of the revenues, and gradually acquired certain prescriptive rights as quasi-proprietors of the estates entrusted to them by the government. In 1793 Lord Cornwallis declared their rights perpetual, and gave over the land of Bengal to the previous quasi-proprietors or zamindars, on condition of the payment of a fixed land tax. This piece of legislation is known as the Permanent Settlement of the Land Revenue. It was designed to "introduce" ideas of property rights to India, and stimulate a market in land. The former aim misunderstood the nature of landholding in India, and the latter was an abject failure.

The Cornwallis Code, while defining the rights of the proprietors, failed to give adequate recognition to the rights of the under-tenants and the cultivators. This remained a serious problem for the duration of British Rule, as throughout the Bengal Presidency ryots (peasants) found themselves oppressed by rack-renting landlords, who knew that every rupee they could squeeze from their tenants over and above the fixed revenue demanded from the Government represented pure profit. Furthermore, the Permanent Settlement took no account of inflation, meaning that the value of the revenue to Government declined year by year, whilst the heavy burden on the peasantry grew no less. This was compounded in the early 19th century by compulsory schemes for the cultivation of opium and indigo, the former by the state, and the latter by British planters. Peasants were forced to grow a certain area of these crops, which were then purchased at below market rates for export. This added greatly to rural poverty.

So unsuccessful was the Permanent Settlement that it was not introduced in the North-Western Provinces (taken from the Marathas during the campaigns of Lord Lake and Arthur Wellesley) after 1831, in Punjab after its conquest in 1849, or in Oudh which was annexed in 1856. These regions were nominally part of the Bengal Presidency, but remained administratively distinct. The area of the Presidency under direct administration was sometimes referred to as Lower Bengal to distinguish it from the Presidency as a whole. Officially Punjab, Agra and Allahabad had Lieutenant-Governors subject to the authority of the Governor of Bengal in Calcutta, but in practice they were more or less independent. The only all-Presidency institutions which remained were the Bengal Army and the Civil Service. The Bengal Army was finally amalgamated into the new British-Indian Army in 1904–5, after a lengthy struggle over its reform between Lord Kitchener, the Commander-in-Chief, and Lord Curzon, the Viceroy.

Straits Settlements

In 1830, the British Straits Settlements on the coast of the Malacca Straits was made a residency of the Presidency of Bengal in Calcutta. The area included the erstwhile Prince of Wales Island and Province Wellesley, as well as the ports of Malacca and Singapore. Previously, the Straits Settlements (formed by the HEIC in 1826) was administered as a separate presidency with George Town as the capital. However, the presidency was found to be too costly to administer. Hence, the HEIC decided to reduce the status of the Straits Settlements from a presidency to a residency of the Presidency of Bengal, which was under the governor-general of India based in Calcutta.[3] As a residency, all administrative decisions and legislations concerning the Straits Settlements were made in Calcutta, and the governor of the Straits Settlements became a mere resident without executive and legislative powers. Overall, this arrangement proved to be ineffective. Without proper representation in Calcutta and due to the distance between the Straits Settlements and Calcutta, the Indian government found it difficult to advance their interests in the Straits such as by cultivating better ties with the Malay states.[3]

Nonetheless, the Straits Settlements remained in the Presidency of Bengal for more than three decades. During this period, the Straits Settlements underwent a number of administrative changes. In 1832, Singapore replaced George Town as the capital of the Straits Settlements. In 1851, direct control over the Straits Settlements was transferred to the Governor-General of India in Calcutta. Under the administration of the East India Company, the Settlements were used as penal settlements for Indian civilian and military prisoners,[7] earning them the title of the "Botany Bays of India".[8]:29 The years 1852 and 1853 saw minor uprisings by convicts in Singapore and Penang.[9]:91 Upset with East India Company rule, in 1857 the European population of the Settlements sent a petition to the British Parliament[10] asking for direct rule. Finally, on 1 April 1867, the Straits Settlements was transferred to the Colonial Office in London to become a crown colony under direct British control.[3]

1905 Partition of Bengal

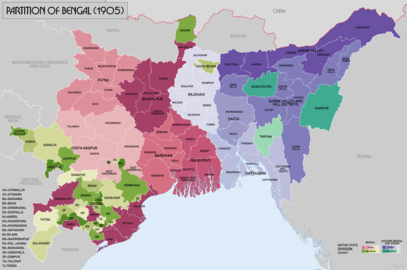

The partition of the large province of Bengal, which was decided upon by Lord Curzon, and Cayan Uddin Ahmet, the Chief Secretary of Bengal carried into execution in October 1905. The Chittagong, Dhaka and Rajshahi divisions, the Malda District and the States of Hill Tripura, Sylhet and Comilla were transferred from Bengal to a new province, Eastern Bengal and Assam; the five Hindi-speaking states of Chota Nagpur, namely Changbhakar, Korea, Surguja, Udaipur and Jashpur State, were transferred from Bengal to the Central Provinces; and Sambalpur State and the five Oriya states of Bamra, Rairakhol, Sonepur, Patna and Kalahandi were transferred from the Central Provinces to Bengal.

The province of West Bengal then consisted of the thirty-three districts of Burdwan, Birbhum, Bankura, Midnapur, Hughli, Howrah, Twenty-four Parganas, Calcutta, Nadia, Murshidabad, Jessore, Khulna, Patna, Gaya, Shahabad, Saran, Champaran, Muzaffarpur, Darbhanga, Monghyr, Bhagalpur, Purnea, Santhal Parganas, Cuttack, Balasore, Angul and Kandhmal, Puri, Sambalpur, Singhbhum, Hazaribagh, Ranchi, Palamau, and Manbhum. The princely states of Sikkim and the tributary states of Odisha and Chhota Nagpur were not part of Bengal, but British relations with them were managed by its government.

The Indian Councils Act 1909 expanded the legislative councils of Bengal and Eastern Bengal and Assam provinces to include up to 50 nominated and elected members, in addition to three ex officio members from the executive council.[11]

Bengal's legislative council included 22 nominated members, of which not more than 17 could be officials, and two nominated experts. Of the 26 elected members, one was elected by the Corporation of Calcutta, six by municipalities, six by district boards, one by the University of Calcutta, five by landholders, four by Muslims, two by the Bengal Chamber of Commerce, and one by the Calcutta Trades Association. Eastern Bengal and Assam's legislative council included 22 nominated members, of which not more than 17 be officials and one representing Indian commerce, and two nominated experts. Of the 18 elected members, three were elected by municipalities, five by district and local boards, two by landowners, four by Muslims, two by the tea interest, one by the jute interest, and one by the Commissioners of the Port of Chittagong.[12]

The partition of Bengal proved highly controversial, as it resulted in a largely Hindu West Bengal and a largely Muslim East. Serious popular agitation followed the step, partly on the grounds that this was part of a cynical policy of divide and rule, and partly that the Bengali population, the centre of whose interests and prosperity was Calcutta, would now be divided under two governments, instead of being concentrated and numerically dominant under the one, while the bulk would be in the new division. In 1906–1909 the unrest developed to a considerable extent, requiring special attention from the Indian and Home governments, and this led to the decision being reversed in 1911.

Reorganisation of Bengal, 1912

At the Delhi Durbar on 12 December 1911, King George V announced the transfer of the seat of the Government of India from Calcutta to Delhi, the reunification of the five predominantly Bengali-speaking divisions into a Presidency (or province) of Bengal under a Governor, the creation of a new province of Bihar and Orissa under a lieutenant-governor, and that Assam Province would be reconstituted under a chief commissioner. On 21 March 1912 Thomas Gibson-Carmichael was appointed Governor of Bengal; prior to that date the Governor-General of India had also served as the governor of Bengal Presidency. On 22 March the provinces of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa and Assam were constituted.[13]

The Government of India Act 1919 increased the number of nominated and elected members of the legislative council from 50 to 125, and the franchise was expanded.[14] Bihar and Orissa became separate provinces in 1936. Bengal remained in its 1912 boundaries until Independence in 1947, when it was again partitioned between the dominions of India and Pakistan.

1947 Partition of Bengal

The British government considered the possibility of an independent, undivided Bengal. The partition was opposed by the last Governor of Bengal Sir Frederick Burrows.[15] On May 8, 1947, Viceroy Earl Mountbatten cabled the British government with a partition plan that made an exception for Bengal. It was the only province that would be allowed to remain independent should it choose to do so. On May 23, the British Cabinet meeting also hoped that Bengal would remain united. British Prime Minister Clement Attlee informed the US Ambassador to the United Kingdom on 2 June 1947 that there was a"distinct possibility Bengal might decide against partition and against joining either Hindustan or Pakistan".[16] On 6 June 1947, the Sylhet referendum gave a mandate for Sylhet Division to be re-united into Bengal. However, Hindu nationalist leaders in West Bengal and conservative East Bengali Muslim leaders were against the prospect.

On 20 June 1947, the Bengal Legislative Assembly met to vote on partition plans. At the preliminary joint session, the assembly decided by 120 votes to 90 that it should remain united if it joined the new Constituent Assembly of Pakistan. Later, a separate meeting of legislators from West Bengal decided by 58 votes to 21 that the province should be partitioned and that West Bengal should join the existing Constituent Assembly of India. In another separate meeting of legislators from East Bengal, it was decided by 106 votes to 35 that the province should not be partitioned and 107 votes to 34 that East Bengal should join Pakistan in the event of partition.[17] There was no vote held on the proposal for an independent United Bengal.

Geography

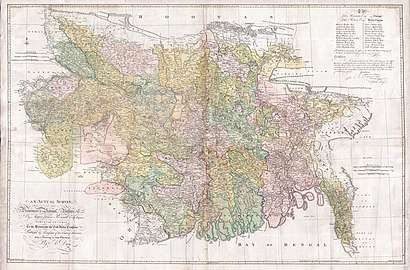

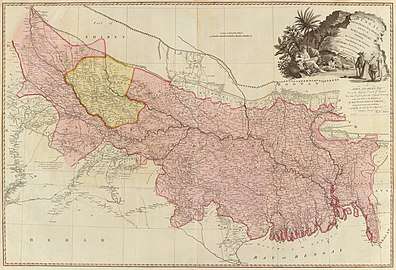

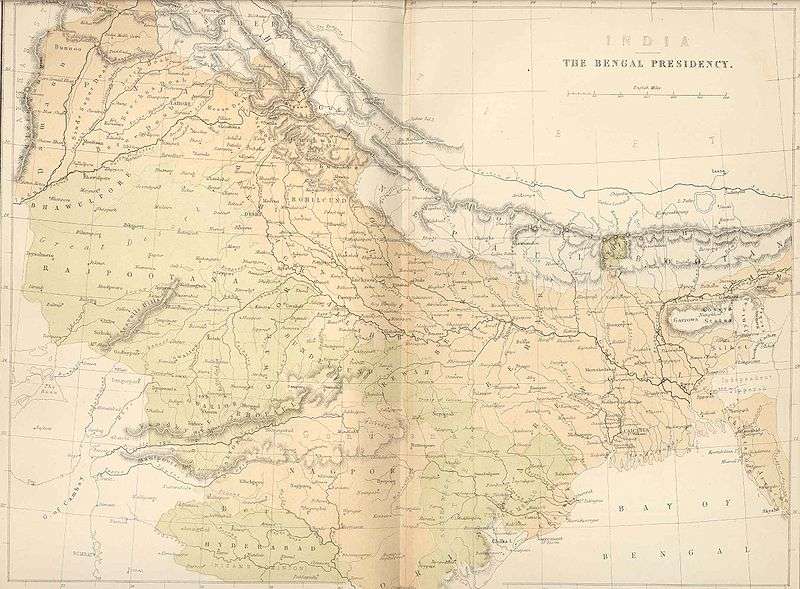

At its greatest extent, the Bengal Presidency stretched from the Khyber Pass in the northwest to Lower Burma and the Malacca Straits in the Far East. Its principal maritime gateway was the Bay of Bengal. The following maps illustrate its territorial evolution.

- Maps of the Bengal Presidency

Bengal Presidency, 1776

Bengal Presidency, 1776 Bengal Presidency, 1786

Bengal Presidency, 1786 Northern part of Bengal Presidency, 1858

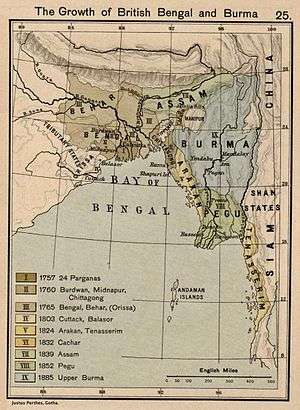

Northern part of Bengal Presidency, 1858 Map showing growth of British rule in Bengal and Burma

Map showing growth of British rule in Bengal and Burma_by_James_Low.jpg) Straits Settlements Residency, including Prince of Wales Island (Penang), Malacca and Singapore

Straits Settlements Residency, including Prince of Wales Island (Penang), Malacca and Singapore Map showing northern regions of the Presidency in 1858, including princely states of Kashmir, Rajputana Agency, and the Punjab

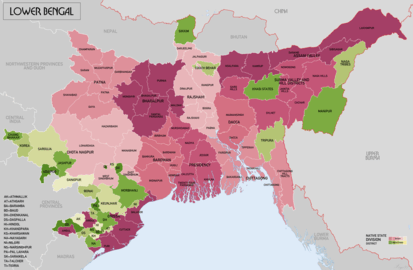

Map showing northern regions of the Presidency in 1858, including princely states of Kashmir, Rajputana Agency, and the Punjab Map denoting Lower Bengal in 1870, including Bengal proper, Orissa, Bihar and Assam; and princely states

Map denoting Lower Bengal in 1870, including Bengal proper, Orissa, Bihar and Assam; and princely states Map showing the result of the partition of Bengal in 1905. The western part (Bengal) gained parts of Orissa, while the eastern part (Eastern Bengal and Assam) regained Assam that had been made a separate province in 1874.

Map showing the result of the partition of Bengal in 1905. The western part (Bengal) gained parts of Orissa, while the eastern part (Eastern Bengal and Assam) regained Assam that had been made a separate province in 1874. Bengal Province in 1931 and adjoining princely states of Hill Tippera and Cooch Behar State

Bengal Province in 1931 and adjoining princely states of Hill Tippera and Cooch Behar State

Government

Initially, Bengal was under the administration of the East India Company, which appointed chief agents/presidents/governors/lieutenant governors in Fort William. The governor of Bengal was concurrently the governor-general of India for many years. The East India Company maintained control with its private armies and administrative machinery. Nevertheless, the East India Company was a quasi-official entity, having received a Royal Charter from Queen Elizabeth I in 1600. The Indian Rebellion of 1857 caused the British government to assume direct control of India's administration under the Government of India Act, 1858. The head of state became the British monarch, who was also given the title of Emperor of India/Empress of India. The monarch was represented through a viceroy. The Viceroy of India was based in the Bengal Presidency until 1911. The Secretary of State for India was also an important official. The Bengal Civil Service managed the provincial government. Modern scholars decry the colonial system as bureaucratic authoritarianism.[18]

Executive councils

Established by Charter Act of 1833, the Governor-General in Council was subordinate to the Court of Directors of the East India Company and the British Crown. The Governor-General in Council in Fort William enacted legislation, such as the prohibition of Persian as an official language under Act no. XXIX of 1837 passed by the President of the Council of India in Council on 20 November 1837.

Judiciary

The Calcutta High Court was set up in 1862. The building was designed on the model of Ypres Cloth Hall in Belgium. The Dacca High Court building was built during the early 20th century, with elements of a Roman pantheon. District courts were established in all district headquarters of the Bengal Presidency. At the district level, tax collectors and revenue officers acted with the power of magistrates. In 1814, the East India Company pressed the Bengal Government to consider the Madras Presidency's model of uniting of judicial and executive powers at the district level. Ultimately Lord Hastings empowered the Governor General-in-Council by Regulation IV of 1821 to authorize the Collectors and Revenue Officers to exercise powers of magistrates. In 1829, magisterial power was given to all Collectors and Revenue Officers. The controversy regarding the lack of separation of powers continued until 1921. During the period from 1853 to 1921, as many as four reports were prepared on the issue of separation of the judiciary from the executive. The first was in 1893, the second in 1900, the third in 1908 and the fourth in 1913. The Islington Commission was formed by the Secretary of State for India in 1912 to enquire into the problems of judicial administration in India. In its report submitted on August 14, 1915; the Commission opined that legislation would be necessary to effect separation of executive and judicial functions of the officers. Despite these reports, the structure as laid down in the Code of Criminal Procedure continued until 1921. On April 5, 1921 the Bengal Legislative Council adopted the following resolution: "This Council recommends to the Government that early steps be taken for the separation of the judiciary from the executive functions in the administration of this Presidency."[19]

Bengal Legislative Council (1862-1947)

The British government began to appoint legislative councils under the Indian Councils Act 1861. The Bengal Legislative Council was established in 1862. It was one of the largest and most important legislative councils in British India. Over the years, the council's powers were gradually expanded from an advisory role to debating government policies and enacting legislation. Under the Government of India Act, 1935, the council became the upper chamber of the Bengali legislature.

Dyarchy (1920–37)

British India's Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms of 1919, enacted in 1921, expanded the Bengal Legislative Council to 140 members to include more elected Indian members. The reforms also introduced the principle of dyarchy, whereby certain responsibilities such as agriculture, health, education, and local government, were transferred to elected ministers. However, the important portfolios like finance, police and irrigation were reserved with members of the Governor's Executive Council. Some of the prominent ministers were Surendranath Banerjee (Local Self-government and Public Health 1921-1923), Sir Provash Chunder Mitter (Education 1921–1924, Local Self-government, Public Health, Agriculture and Public Works 1927–1928), Nawab Saiyid Nawab Ali Chaudhuri (Agriculture and Public Works) and A. K. Fazlul Huq (Education 1924). Bhupendra Nath Bose and Sir Abdur Rahim were Executive Members in the Governor's Council.[20]

Bengal Legislative Assembly (1935-1947)

The Government of India Act, 1935 established the Bengal Legislative Assembly as the lower chamber of the Bengali legislature. It was a 250-seat assembly where most members were elected by either the General Electorate or the Muslim Electorate (under the Communal Award). Other members were nominated. The separate electorate dividing Muslims from the general electorate was deeply controversial. The Prime Minister of Bengal was a member of the assembly.

In the 1937 election, the Congress emerged as the single largest party but short of an absolute majority. The second-largest party was the Bengal Provincial Muslim League (BPML), followed in third place by the Krishak Praja Party. The BPML, Krishak Praja Party and independent legislators formed a coalition government.[21][22] A. K. Fazlul Huq, a founder of the BPML who later broke away to form the Krishak Praja Party, was elected as parliamentary leader and prime minister. Huq pursued a policy of Hindu-Muslim unity. His cabinet included leading Hindu and Muslim figures, including Nalini Ranjan Sarkar (finance), Bijoy Prasad Singha Roy (revenue), Maharaja Srish Chandra Nandy (communications and public works), Prasanna Deb Raikut (forest and excise), Mukunda Behari Mallick (cooperative credit and rural indebtedness), Sir Khwaja Nazimuddin (home), Nawab Khwaja Habibullah (agriculture and industry), Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy (commerce and labour), Nawab Musharraf Hussain (judicial and legislative affairs), and Syed Nausher Ali (public health and local self-government).[23] Huq promoted financial and land reforms with the Bengal Agricultural Debtors' Act (1938), The Money Lenders' Act (1938), and the Bengal Tenancy (Amendment) Act (1938). He introduced the Primary Education Bill to make primary education free and compulsory. He established schools such as the Lady Brabourne College. In 1941, Prime Minister Huq joined the Viceroy's Defence Council in support of Allied war efforts. In a letter to Governor John Herbert, Huq called for the resurrection of a Bengal Army. He wrote "I want you to consent to the formation of a Bengali Army of a hundred thousand young Bengalis consisting of Hindu and Muslim youths on a fifty-fifty basis. There is an insistent demand for such a step being taken at once, and the people of Bengal will not be satisfied with any excuses. It is a national demand which must be immediately conceded".[24] Huq supported the adoption of the Lahore Resolution in 1940. He envisaged Bengal as one of the "independent states" outlined by the resolution.

The first Huq cabinet dissolved after the BPML withdrew from his government. Huq then formed a second coalition with the Hindu Mahasabha led by Syama Prasad Mukherjee. This cabinet was known as the Shyama-Huq Coalition.[23] The cabinet included Nawab Bahabur Khwaja Habibullah, Khan Bahadur Abdul Karim, Khan Bahadur Hashem Ali Khan, Shamsuddin Ahmed, Syama Prasad Mukherjee, Santosh Kumar Bose and Upendranath Barman. Huq's government fell in 1943 and a BPML government under Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin as Prime Minister was formed. Nazimuddin's tenure coincided with the Bengal famine of 1943. His government was replaced by Governor's rule. After the end of World War II, elections were held in 1946 in which the BPML won an overwhelming majority of 113 seats in the 250-seat assembly. A government under Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy was formed.[25] Prime Minister Suhrawardy continued with the policy of power-sharing between Hindus and Muslims. He also advocated a plan for a Bengali sovereign state with a multiconfessionalist political system. The breakdown of Hindu-Muslim unity across India eventually upended Bengali power-sharing. Religious violence, including the Noakhali riots and Direct Action Day riots, contributed to the polarization. When the Bengal Assembly met to vote on Partition, most West Bengali legislators held a separate meeting and resolved to partition the province and join the Indian union. Most East Bengali legislators favored an undivided Bengal.

The Bengal Assembly was divided into the West Bengal Legislative Assembly and East Bengal Legislative Assembly during the Partition of British India.

Civil liberties

English common law was applied to Bengal. Local legislation was enacted by the Legislative Council and Legislative Assembly. Case law was also an important source of law. Many laws enacted in British Bengal are still in use today, including the Indian Penal Code. In 1919, the Rowlatt Act extended wartime powers under the Defence of India Act 1915, including arbitrary arrests and trial without juries. Press freedom was muzzled by the Indian Press Act 1910. The Seditious Meetings Act 1908 curtailed freedom of assembly. Regulation III of 1818 was also considered draconian. King George V granted a royal amnesty to free political prisoners. Some draconian laws were repealed, including the Rowlatt Act.[26] Despite being a common law jurisdiction, British India did not enjoy the same level of protection for civil liberties as in the United Kingdom. It was only after independence in 1947 and the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, that human rights were clearly enshrined in law.

Princely states

Princely states were autonomous principalities under the suzerainty of the British Crown in India. Initially, the Bengal Presidency managed the British government's relations with most princely states in the northern subcontinent, extending from Jammu and Kashmir in the north to Manipur in the northeast. An Agency was often formed to be the liaison between the government and the princely states. The largest of these agencies under Bengal once included the Rajputana Agency. Other agencies covered the Chota Nagpur Tributary States and the Orissa Tributary States. Agents were also appointed to deal with tribal chiefs, such as the three tribal kings in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. At the time of the partition of India in 1947, the jurisdiction of the Bengal States Agency included Cooch Behar State and Hill Tipperah.

Himalayan kingdoms

Bengal was strategically important for the Himalayan regions of Nepal, Tibet, Bhutan and Sikkim. The Anglo-Nepalese War between the East India Company and the Kingdom of Nepal was concluded with the Treaty of Sugauli, which ended Gorkha territorial expansion. The Treaty of Titalia was signed in 1817 between the HEIC and the Kingdom of Sikkim to establish British hegemony over Sikkim. The Bhutan War in the 1860s saw the Kingdom of Bhutan lose control of the Bengal Duars to the British. The British Expedition to Tibet took place between 1903 and 1904. It resulted in the Treaty of Lhasa which acknowledged Qing China's supremacy over Tibet.

Foreign relations

The United States of America began sending envoys to Fort William in the 18th-century. President George Washington nominated Benjamin Joy as the first Consul to Fort William on 19 November 1792. The nomination was supported by the erstwhile Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and approved by the U. S. Senate on 21 November 1792. Benjamin Joy reached Calcutta in 1794. The HEIC did not recognize Joy as an official consul but allowed him to be a Commercial Agent.[27] The American Consulate General was established during formal British rule. A consular agency for Chittagong was created in the 1860s. Many other countries also set up consulates in Calcutta.

Education

British rule saw the establishment of liberal arts colleges in many districts of Bengal. There were only two full-fledged universities in Bengal during British rule, including the University of Calcutta and the University of Dacca. Both universities were represented in the Bengal Legislative Assembly under the Government of India Act, 1935.

Primary education was mandatory under the Compulsory Education Acts.[28] Despite significant advances and the emergence of a large educated middle class, most of the population did not have access to a proper education. During 1946–47, there were 5,298 high schools with an enrolment of 21,99,000 pupils whereas the corresponding figures for 1916-17 were 1,507 and 57,200. The demand for secondary education increased with the growth of political consciousness amongst the masses. The result was the establishment of schools in villages and towns where backward communities could enroll. Female education too received a good deal of attention during the period. Consequently, between 1921–22 and 1946–47, the number of educational institutions for girls nearly doubled.[28] Some of the leading schools included the Oriental Seminary in Calcutta, the St. Gregory's High School in Dacca, the Rajshahi Collegiate School in Rajshahi and the Chittagong Collegiate School in Chittagong. European missionaries, Hindu philanthropists and Muslim aristocrats were influential promoters of education. Ethnic minorities maintained their own institutions, such as the Armenian Pogose School.

Each district of Bengal had a district school, which were the leading secondary institutions. Due to Calcutta being the colonial capital, the city had a large concentration of educational institutions. It was followed by Dacca, which served as a provincial capital between 1905 and 1912. Libraries were established in each district of Bengal by the colonial government and the Zamindars. In 1854, four major public libraries were opened, including the Bogra Woodburn Library, the Rangpur Public Library, the Jessore Institute Public Library and the Barisal Public Library. Northbrook Hall was established in 1882 in honor of Governor-General Lord Northbrook. Other libraries built include the Victoria Public Library, Natore (1901), the Sirajganj Public Library (1882), the Rajshahi Public Library (1884), the Comilla Birchandra Library (1885), the Shah Makhdum Institute Public Library, Rajshahi (1891), the Noakhali Town Hall Public Library (1896), the Prize Memorial Library, Sylhet (1897), the Chittagong Municipality Public Library (1904) and the Varendra Research Library (1910). In 1925, the Great Bengal Library Association was established.[29]

Europeans played an important role in modernizing the Bengali language. The first book on Bengali grammar was compiled by a Portuguese missionary.[30] English was the official language. The use of Persian as an official language was discontinued by Act no. XXIX of 1837 passed by the President of the Council of India in Council on 20 November 1837. However, Persian continued to be taught in some institutions. Several institutions had Sanskrit and Arabic faculties.[31] The following includes a partial list of notable colleges, universities and learned societies in the Bengal Presidency.

- Asiatic Society

- Scottish Church College

- Presidency College

- Fort William College

- City College, Calcutta

- Calcutta Medical College

- University of Calcutta

- Dhaka College

- Dhaka Medical College

- Ahsanullah School of Engineering

- University of Dhaka

- Chittagong College

- Rajshahi College

- Carmichael College

- Victoria College

- Bethune College

- Eden College

- Cotton College

- Calcutta School of Tropical Medicine

- Bose Institute

- Serampore College

- Ananda Mohan College

- Visva-Bharati University

- St. Xavier's College

- Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science

- Sanskrit College

- Calcutta Madrasa

- Academy of Fine Arts

- Indian Science Congress Association

- Agri Horticultural Society of India

- Geological Survey of India

- Botanical Survey of India

- Calcutta Mathematical Society

- Archaeological Survey of India

- Anthropological Survey of India

- Rajendra College

Economy

.jpg)

In Bengal, the British inherited from the Mughals the biggest revenue earnings in the Indian subcontinent. For example, the revenue of pre-colonial Dhaka alone was 1 million rupees in the 18th century (a high amount in that era).[32] Mughal Bengal accounted for 12% of the world's GDP and was a major exporter of silk, cotton, saltpeter, and agricultural produce. With its proto-industrial economy, Bengal contributed to the first Industrial Revolution in Britain (particularly in textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution). After 1757, the British placed Bengal under company rule (which led to Bengali deindustrialization).[33][34] Other European powers in the region included the French East India Company, the Dutch East India Company, the Ostend Company and the Danish East India Company. Initially, the English East India Company promoted opium cultivation which caused the Opium Wars with Qing China. The East India Company's promotion of indigo farming caused the Indigo revolt. The British were much criticized for favoring textile imports and suppressing local muslin production. The chaos of the Company rule period culminated in the Indian Mutiny in 1857. In 1858, the British government gained direct control of Indian administration. Bengal was plugged into the market-driven economy and trade networks of the British Empire.

The Bengal Presidency had the largest gross domestic product in British India.[35] The first British colonial banks in the Indian subcontinent were founded in Bengal. These included the General Bank of Bengal and Bihar (1733); Bank of Hindostan (1770), Bank of Bengal (1784); and the General Bank of India (1786). Other banks in Bengal included the Bank of Calcutta (1806), Union Bank (1829); Government Savings Bank (1833); The Bank of Mirzapore (c. 1835); Dacca Bank (1846); Kurigram Bank (1887), Kumarkhali Bank (1896), Mahaluxmi Bank, Chittagong (1910), Dinajpur Bank (1914), Comilla Banking Corporation (1914), Bengal Central Bank (1918), and Comilla Union Bank (1922).[36] Loan offices were established in Faridpur (1865), Bogra (1872), Barisal (1873), Mymensingh (1873), Nasirabad (1875), Jessore (1876), Munshiganj (1876), Dacca (1878), Sylhet (1881), Pabna (1882), Kishoreganj (1883), Noakhali (1885), Khulna (1887), Madaripur (1887), Tangail (1887), Nilphamari (1894) and Rangpur (1894).[36]

The earliest records of securities dealings are the loan securities of the British East India Company. In 1830, bourse activities in Calcutta were conducted in the open air under a tree.[37] The Calcutta Stock Exchange was incorporated in 1908. Some of the leading companies in British Bengal included Messrs. Alexander and Co, Waldies, Martin Burn, M. M. Ispahani Limited, James Finlay and Co., A K Khan & Company, the Calcutta Chemical Company, Bourne & Shepherd, the Indo-Burmah Petroleum Company, Orient Airways, Shaw Wallace, Carew & Co, Aditya Birla Group, Tata Group, Balmer Lawrie, Biecco Lawrie, Braithwaite, Burn & Jessop Construction Company, Braithwaite & Co., Bridge and Roof Company, Britannia Industries, Burn Standard Company and Andrew Yule and Company. Some of these enterprises were nationalized after the Partition of India.

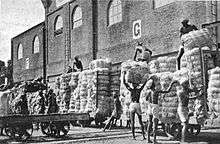

Agricultural products included rice, sugarcane and vegetables. The main cash crops were jute and tea. The jute trade was central to the British Bengali economy. Bengal accounted for the bulk of the world's jute production and export. Raw jute was sourced from the hinterland of Eastern Bengal. The British government declared the Port of Narayanganj as a "Tax Free Port" in 1878.[38] Rally Brothers & Co. was one of the earliest British companies in the jute business of Narayanganj. British firms used middlemen, called beparis, to source raw jute from the hinterland. In 1907, 20 firms were engaged in the jute trade of Narayanganj, including 18 European firms.[38] Hindu merchants opened several cotton mills in the 1920s, including the Dhakeshwari Cotton Mill, the Chittaranjan Cotton Mill and the Laxmi Narayan Cotton Mill.[39] Other goods traded in Narayanganj included timber, salt, textiles, oil, cotton, tobacco, pottery, seeds and betel nut. Raw goods were processed by factories in Calcutta, especially jute mills. The Port of Chittagong was re-organized in 1887 under the Port Commissioners Act. Its busiest trade links were with British Burma, including the ports of Akyab and Rangoon;[40] and other Bengali ports, including Calcutta, Dhaka and Narayanganj.[41] In the fiscal year 1889–90, Chittagong handled exports totalling 125,000 tons.[42] The Strand Road was built beside the port. In 1928, the British government declared Chittagong as a "Major Port" of British India.[43] Chittagong's port was used by Allied Forces of World War II during the Burma Campaign.

The Port of Calcutta was the largest seaport of British India. The port was constructed by the British East India Company. It was one of the busiest ports in the world during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Calcutta was a major trading port with links to ports across the British Empire. Its local hinterland spanned beyond Bengal to include north and northeast India, the Himalayan kingdoms and Tibet. The Bay of Bengal became one of the busiest shipping hubs in the world, rivaling the traffic of ports on the Atlantic.[44] Calcutta was also an important naval base in World War II and was bombed by the Japanese.

Chambers of commerce were established. The Bengal Chamber of Commerce was established in 1853. The Narayanganj Chamber of Commerce was set up in 1904.[45] The textile trade of Bengal enriched many merchants. For example, Panam City in Sonargaon saw many townhouses built for wealthy textile merchants.

Tea became a major export of Bengal. Northwestern Bengal became the center of Darjeeling tea cultivation in the foothills of the Himalayas. Darjeeling tea became one of the most reputed tea varieties in the world. The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway was constructed in the tea plantation zone.[46] In eastern Bengal, the Sylhet and Chittagong hilly regions became hubs of tea production. Assam tea was produced in the northeastern part of the Bengal Presidency.

Aside from the British, the chief beneficiaries of the colonial economy were the Zamindars (landed gentry). The Permanent Settlement enforced a system in which peasants were indebted to the Zamindars. The peasants rented land from the Zamindars and became tenant farmers. Strong control of land by the Zamindars meant the British had few headaches in exploiting trade and business. However, Bengal received little attention for industrialization due to the entrenched peasant-zamindar relationship under the Permanent Settlement.[47] The Zamindars of Bengal built mansions, lodges, modern bungalows, townhouses, and palaces on their estates. Some of the largest mansions include the Hazarduari Palace in Murshidabad, the Ahsan Manzil on the Nawab of Dhaka's estate, the Marble Palace in Calcutta, and the Cooch Behar Palace.

Infrastructure and transport

Railways

After the invention of railways in Britain, British India became the first region in Asia to have a railway. The East Indian Railway Company introduced railways to Bengal. The company was established on 1 June 1845 in London by a deed of settlement with a capital of £4,000,000. Its first line connected Calcutta with towns in northern India. By 1859, there were 77 engines, 228 coaches and 848 freight wagons. Large quantities of sal tree wood were imported from Nepal to design the sleepers.[48][49] In 1862, railways were introduced to eastern Bengal with the Eastern Bengal Railway. The first line connected Calcutta and Kushtia. By 1865, the railway was extended to Rajbari on the banks of the Padma River. By 1902, the railway was extended to Assam. The Assam Bengal Railway was established to serve the northeastern part of the Bengal Presidency, with its terminus in Chittagong.[50]

A new 250-km long metre gauge (1000 mm) railway line known as the Northern Bengal State Railway was constructed between 1874 and 1879 from Sara (on the left bank of Padma) to Chilahati (extended up to Siliguri at the foot of the Himalayas). The line branched off from Parbatipur to Kaunia on the east and from Parbatipur to Dinajpur on the west.[50] The Bengal and North Western Railway was set up in 1882 to link towns in the Oudh region with Calcutta. Several railway bridges, such as the Hardinge Bridge, were built over rivers in Bengal. In 1999, UNESCO recognized the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway as a World Heritage Site.

Roads and highways

In the 1830s the East India Company began to rebuild the ancient Grand Trunk Road into a paved highway. The company required the road for commercial and administrative purposes. It linked Calcutta to Peshawar in the North-West Frontier Province. For the project, the company founded a college to train and employ local surveyors, engineers, and overseers.[51][52] In the east, the road extended to Sonargaon, Comilla and Chittagong. After the first partition of Bengal in 1905, newly built highways connected the inaccessible areas of Assam and the Chittagong Hill Tracts. All district towns were connected by an inter-district road network.[53]

Waterways

A ghat in Bengal refers to a river port. The busiest river ports included the Port of Calcutta, the Port of Dhaka, the Port of Narayanganj and Goalundo Ghat. From the late 19th century, those travelling to East Bengal, Assam or Burma took the steamer from Goalondo, a small station at the confluence of the Padma and the Brahmaputra, where the Eastern Bengal Express from Sealdah terminated. The Goalondo steamer then travelled up to Narayanganj in Dacca and from thereon people moved ahead to Sylhet or Chittagong or further on into Burma on the one side and to the tea gardens of Assam on the other. The overnight journey saw passengers being served a special chicken curry, known as the Goalondo Steamer Chicken. It was cooked by Muslim boatmen and became a popular dish like the Madras Club Qorma and the Railway Mutton Curry.[54]

After the first partition of Bengal in 1905, a number of new ferry services were introduced connecting Chittagong, Dhaka, Bogra, Dinajpur, Rangpur, Jalpaiguri, Maldah and Rajshahi. This improved communication network boosted trade and commerce.[53]

Aviation

An early attempt at manned flight in Bengal was by a young American balloonist. Invited to perform by the Nawab of Dhaka, at 6.20 pm on 16 March 1892, the woman set off to fly from the southern bank of the River Buriganga to the roof of the Nawab's palace across the river. But a gusting wind carried her off to the gardens of Shahbag, where her balloon became stuck in a tree. She was killed in her fall to the ground, and lies interred in the Christian graveyard at Narinda in Old Dhaka.[55][56]

An airfield opened next to a Royal Artillery station on the outskirts of Calcutta.[57] The Governor of Bengal Sir Stanley Jackson opened the Bengal Flying Club in Calcutta's aerodrome in February 1929.[58] In 1930, the airfield was upgraded into a full-fledged airport.[59] It was popularly known as Dum Dum Airport. Imperial Airways began flights from London to Australia via Calcutta in 1933.[60] Air Orient began scheduled stops as part of its Paris to Saigon route.[61] KLM operated a route from Amsterdam to Batavia (Jakarta) via Calcutta.[62] Calcutta emerged as a stopover for many airlines operating routes between Europe, Indochina and Australasia.[63] The flight of Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan, who attempted to cicumnavigate the world, made a stopover in Calcutta in 1937.[64] Local airlines included Tata Air Services and Orient Airways. Bengal played an important role for the air operations of the Allied forces of World War II. The Royal Air Force operated airfields across Bengal during the Burma Campaign. Aircraft of the United States Army Air Forces were also stationed in Bengal.

The following includes a partial list of airports and airfields established during British rule in Bengal. Airfields were used by Allied Forces during World War II.

- Calcutta Airport

- Tejgaon Airfield

- Chittagong Airfield

- Sylhet Airport

- Dohazari Airfield

- Shamshernagar Airport

- Lalmonirhat Airport

- Thakurgaon Airport

- Saidpur Airport

- Bogra Airport

- Ishwardi Airport

- Comilla Airport

- Fenny Airfield

- Hathazari Airfield

- Asansol Airfield

- Chakulia Airfield

- Piardoba Airfield

- Guskhara Airfield

- Dudhkundi Airfield

- Pandaveswar Airfield

- Charra Airfield

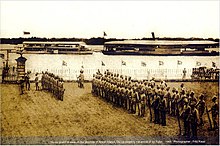

Military

The Bengal Army was one of the Presidency Armies of British India. It was formed by the East India Company. The Commander-in-Chief of the Bengal Army was concurrently the Commander-in-Chief, India from 1853 to 1895, as the Bengal Army was the largest of the Presidency Armies.[65] Recruits initially included Europeans and soldiers of the former Nawabs' Armies. Many of the recruits were from Bihar and Oudh. The Gurkhas were also recruited under the Bengal Army. In 1895, the Bengal Army was merged into the British Indian Army. The British Indian Army had a Bengal Command between 1895 and 1908.

Major military engagements affecting British Bengal included the First Anglo-Burmese War, the Anglo-Nepalese War, the First Afghan War, the Opium Wars, the Bhutan War, the Second Anglo-Afghan War, World War I, and the Burma Campaign of World War II. The chief British base in Bengal was Fort William. Across the subcontinent, the British often converted Mughal forts into military bases, such as in Delhi and Dhaka. The British also built cantonments, including Dhaka Cantonment and Chittagong Cantonment. Many Allied soldiers killed in Burma were buried in cemeteries in Chittagong and Comilla. The graveyards include the Commonwealth War Cemetery, Chittagong and Mainamati War Cemetery, which are maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Famine

Famine struck Bengal several times during British rule. The Great Bengal famine of 1770 endured till 1773. The East India Company was heavily criticized for neglecting the food security the population. The repeated bouts of famine in India, coupled with other abuses against the population, caused the British Parliament to gradually remove the monopoly of the East India Company, curtail the Company's powers and eventually replace it with crown rule. Warren Hastings, who served as Governor of Bengal from 1772 to 1774, was censured by Westminster for the abuses of the Company. Ironically, Hastings had set about to reform the Company's practices and was later acquitted of any wrongdoing. During the trial of Hastings, however, Edmund Burke delivered a scathing indictment of malpractice by the Company, condemning it for "injustice and treachery against the faith of nations". Burke stated "With various instances of extortion and other deeds of maladministration....With impoverishing and depopulating the whole country.....with a wanton and unjust, pernicious, exercise of his powers.....in overturning the ancient establishments of the country......With cruelties unheard of and devastations almost without name......Crimes which have their rise in the wicked dispositions of men- in avarice, rapacity, pride, cruelty, malignity, haughtiness, insolence, ferocity, treachery, cruelty, malignity of temper - in short, nothing that does not argue a total extinction of all moral principle, that does not manifest an inveterate blackness of heart, a heart blackened to the very blackest, a heart corrupted, gangrened to the core.....We have brought before you the head (Hastings)....one in whom all the frauds, all the peculations, all the violence, all the tyranny in India are embodied".[66]

The Bengal Presidency endured a vast famine between 1873 and 1874. The Bengal famine of 1943 killed an estimated 3 million people during World War II. People died of starvation, malaria, or other diseases aggravated by malnutrition, population displacement, and lack of healthcare. Britain's wartime Prime Minister Winston Churchill is blamed by critics in India (i.e. Amartya Sen and Shashi Tharoor) for causing the famine. When British civil servants sent letters to London regarding the famine situation, Churchill once responded by saying "Why hasn't Gandhi died yet?".[67][68] Churchill's defenders, however, argue that it is an exaggeration to blame him for the wartime hunger crisis. Arthur Herman notes "The idea that Churchill was in any way ‘responsible’ or ‘caused’ the Bengal famine is of course absurd. The real cause was the fall of Burma to the Japanese, which cut off India's main supply of rice imports when domestic sources fell short, which they did in Eastern Bengal after a devastating cyclone in mid-October 1942".[69]

Culture

Literary development

The English language replaced Persian as the official language of administration. The use of Persian was prohibited by Act no. XXIX of 1837 passed by the President of the Council of India in Council on 20 November 1837,[31][70] bringing an end to six centuries of Indo-Persian culture in Bengal. The Bengali language received increased attention. European missionaries produced the first modern books on Bengali grammar. In pre-colonial times, Hindus and Muslims would be highly attached to their liturgical languages, including Sanskrit and Arabic. Under British rule, the use of Bengali widened and it was strengthened as the lingua franca of the native population. Novels began to be written in Bengali. The literary polymath Rabindranath Tagore was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913. The cultural activist Kazi Nazrul Islam gained popularity as British India's Rebel Poet. Jagadish Chandra Bose pioneered Bengali science fiction. Begum Rokeya, author of Sultana's Dream, became an early feminist science fiction author.

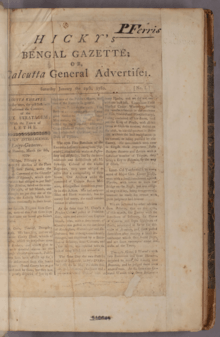

Media

Numerous newspapers were published in British Bengal since the 18th-century. Many were in English. Hicky's Bengal Gazette was a major weekly publication. The first Bengali periodicals appeared in the 19th-century. The Calcutta Journal became the first daily newspaper in British India.[71] Other newspapers included the Dacca News and The Bengal Times. Radio channels began transmitting in 1927.[72]

Visual arts

European painters produced numerous works in Bengal since the 18th-century. European photographers also worked in the region. The modernist Bengal school of painting evolved in the province. European sculptures were widely imported by wealthy Zamindars. In the 1940s, Zainul Abedin emerged as a modernist painter depicting poverty and the Bengal famine.

Calcutta Time

Calcutta Time was the time zone of the Bengal Presidency. It was established in 1884. It was one of the two time zones of British India. In the latter part of the 19th-century, Calcutta Time was the most prevalent time used in the Indian part of the British Empire with records of astronomical and geological events recorded in it.[73][74]

Cinema

The Royal Bioscope Company began producing Bengali cinema in 1898, producing scenes from the stage productions of a number of popular shows[75] at the Crown Theatre in Dacca and the Star Theater, Minerva Theater, and Classic Theater in Calcutta.

The Madan Theatre started making silent films in Calcutta in 1916. The first Bengali feature film, Billwamangal, was produced and released in 1919 under the banner of the Madan Theatre. The movie was directed by Rustomji Dhotiwala and produced by Priyonath Ganguli. A Bengali film company called the Indo British Film Co was soon formed in Calcutta by Dhirendra Nath Ganguly. Ganguly directed and wrote Bilat Ferat in 1921, which was the first production of the Indo British Film Co. Jamai Shashthi (1931) was one of the earliest Bengali talkies.

In 1927–28, the Dhaka Nawab Family produced a short film named Sukumary (The Good Girl).[76] After the success of Sukumary, the Nawab's family went for a bigger venture.[77] To make a full-length silent film, a temporary studio was made in the gardens of the family's estate, and they produced a full-length silent film titled The Last Kiss, released in 1931.[78][79] The “East Bengal Cinematograph Society” was later established in Dacca.

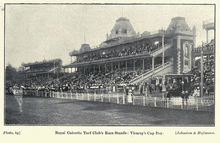

Sports

Cricket started being played in the 1790s. The Calcutta Cricket Club was set up in 1792. For horse racing, the Royal Calcutta Turf Club was set up in 1847. It became British India's equivalent of the Jockey Club in England in terms of arbitrating matters related to racing. In addition to horse races, the club also launched polo matches among natives and colonialists. Races at the Calcutta Race Course were once among the most important social events of the calendar, opened by the Viceroy of India. During the 1930s the Calcutta Derby Sweeps was a leading sweepstake game in the world. A racecourse was also set up in Ramna by the Dacca Club.[80] The Bengal Public Gaming (Amendment) Act (Act No. IV of 1913) excluded horse racing from the gambling law.[81]

Bengal renaissance

The Bengal renaissance refers to social reform movements during the 19th and early 20th centuries in the region of Bengal in undivided India during the period of British rule. Historian Nitish Sengupta describes it as having started with reformer and humanitarian Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1775–1833), and ended with Asia's first Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941).[82] This flowering of religious and social reformers, scholars, and writers is described by historian David Kopf as "one of the most creative periods in Indian history".[83] These movements were most prevalent in Bengali Hindu society, such as through the Brahmo Samaj. There was a growing cultural awakening in Bengali Muslim society, including the emergence of Mir Mosharraf Hossain as the first Muslim novelist of Bengal; Kazi Nazrul Islam as a celebrated poet who merged Bengali and Hindustani influences; Begum Rokeya and Nawab Faizunnesa as feminist educators; Kaykobad as an epic poet; and members of the Freedom of Intellect Movement.

Bengal played a major role in the Indian independence movement and the Pakistan movement. The earliest organized anti-colonial groups appeared in Bengal. The region produced many of the subcontinent's political leaders during the early 20th century. Political parties and rebel groups were formed across the region.

Architecture

Civic architecture began following European styles after the advent of the East India Company's authority. The Indo-Saracenic style, merging Gothic and Indo-Islamic architecture, was started by British architects in the late 19th-century. While cities such as Calcutta and Dacca featured more civic architecture, country houses were built in many towns and villages across Bengal. Art deco influences began in the 1930s. Wealthy Bengali families (especially zamindar estates) employed European firms to design houses and palaces.

- Architecture in British Bengal

.jpeg) Howrah Bridge in 1945

Howrah Bridge in 1945

Writer's Building

Writer's Building

.jpg) Hardinge Bridge, 1915

Hardinge Bridge, 1915 Dacca College, 1904

Dacca College, 1904 Dacca Madrasa, 1904

Dacca Madrasa, 1904 Nawab's Shahbagh Garden, 1904

Nawab's Shahbagh Garden, 1904

Society

Bengali society remained deeply conservative during the colonial period with the exception of social reform movements. Historians have argued that the British used a policy of divide and rule among Hindus and Muslims. This meant favoring Hindus over Muslims and vice versa in certain sectors. For example, after the Permanent Settlement, Hindu merchants such as the Tagore family were awarded large land grants that previously belonged to the Mughal aristocracy. In Calcutta, where Hindus formed a majority, wealthy Muslims were often given favors over Hindus. One aspect that benefitted the Hindu community was increased literacy rates. Many Muslims, however, remained alienated from English education after the abolition of Persian. Bengali society continued to experience religious nationalism which led to the partition of Bengal in 1947.

British Bengali cities included a cosmopolitan population, including Armenians and Jews. Anglo-Indians formed a prominent part of the urban population. Several Gentlemen's clubs were established, including the Bengal Club, Calcutta Club, Dacca Club, Chittagong Club, Tollygunge Club and Saturday Club.

References

- William Dalrymple (10 September 2019). The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4088-6440-1.

- Parthasarathi, Prasannan (2011), Why Europe Grew Rich and Asia Did Not: Global Economic Divergence, 1600–1850, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-139-49889-0

- "The Straits Settlements becomes a residency - Singapore History". Eresources.nlb.gov.sg. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. II 1909, pp. 452–472

- Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. II 1909, pp. 473–487

- Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. II 1909, pp. 488–514

- Anderson, C (2007) The Indian Uprising of 1857–8: prisons, prisoners, and rebellion, Anthem Press. P14

- S. Nicholas and P. R. Shergold, "Transportation as Global Migration", in S. Nicholas (ed.) (1988) Convict Workers: Reinterpreting Australia's Past, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

- Turnbull, CM, "Convicts in the Straits Settlements 1826–1867" in Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1970, 43, 1

- Petition reprinted in Straits Times, 13 October 1857

- Ilbert, Sir Courtenay Peregrine (1907). "Appendix II: Constitution of the Legislative Councils under the Regulations of November 1909", in The Government of India. Clarendon Press. pp. 431.

- Ilbert, Sir Courtenay Peregrine (1907). "Appendix II: Constitution of the Legislative Councils under the Regulations of November 1909", in The Government of India. Clarendon Press. pp. 432–5.

- Ilbert, Sir Courtenay Peregrine (1922). The Government of India, Third Edition, revised and updated. Clarendon Press. pp. 117–118.

- Ilbert, Sir Courtenay Peregrine (1922). The Government of India, Third Edition, revised and updated. Clarendon Press. p. 129.

- The Transfer of Power in India By V.P. Menon

- Shoaib Daniyal (6 January 2019). "Why did British prime minister Attlee think Bengal was going to be an independent country in 1947?". Scroll.in. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Mukherjee, Soumyendra Nath (1987). Sir William Jones: A Study in Eighteenth-century British Attitudes to India. Cambridge University Press. Page 203. ISBN 978-0-86131-581-9.

- Associate Professor History Ayesha Jalal; Ayesha Jalal (6 April 1995). Democracy and Authoritarianism in South Asia: A Comparative and Historical Perspective. Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-521-47862-5.

- "Separation of the Judiciary - Banglapedia". En.banglapedia.org. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- The Working Of Dyarchy In India 1919 1928. D.B.Taraporevala Sons And Company.

- Jalal, Ayesha (1994). The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0-521-45850-4.

- Sanaullah, Muhammad (1995). A.K. Fazlul Huq: Portrait of a Leader. Homeland Press and Publications. p. 104. ISBN 9789848171004.

- http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Huq,_AK_Fazlul

- Syed Ashraf Ali. "Sher-e-Bangla: A natural leader". The Daily Star. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- Nalanda Year-book & Who's who in India. 1946.

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/gentlemanly-terrorists/reforms-of-1919-montaguchelmsford-the-rowlatt-act-jails-commission-and-the-royal-amnesty/D97CA2DF6D0AEBDD9AD2066DB1504C04/core-reader

- https://in.usembassy.gov/embassy-consulates/kolkata/

- "Education - Banglapedia". En.banglapedia.org. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Rahman, Md Zillur (2012). "Library". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- https://www.dhakatribune.com/uncategorized/2014/01/24/voce-fala-bangla

- "Persian - Banglapedia". En.banglapedia.org. 15 February 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Golam Rabbani (1997). Dhaka: From Mughal Outpost to Metropolis. Upl. pp. 14–19. ISBN 978-984-05-1374-1.

- Om Prakash, "Empire, Mughal", History of World Trade Since 1450, edited by John J. McCusker, vol. 1, Macmillan Reference USA, 2006, pp. 237–240, World History in Context. Retrieved 3 August 2017

- Indrajit Ray (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757-1857). Routledge. pp. 57, 90, 174. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1.

- "Reimagining the Colonial Bengal Presidency Template (Part I)". Daily sun. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- "Banking System, Modern - Banglapedia". En.banglapedia.org. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- "Lights on at Lyons Range - Bombay bourse boost for city exchange". Telegraphindia.com. 30 October 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Ghulam M. Suhrawardi (6 November 2015). Bangladesh Maritime History. FriesenPress. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-4602-7278-7.

- "Narayanganj - Banglapedia". En.banglapedia.org. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- J. Forbes Munro (2003). Maritime Enterprise and Empire: Sir William Mackinnon and His Business Network, 1823-93. Boydell Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-85115-935-5.

- Willis's Current notes. London: G. Willis. 1886. p. 16.

- Tauheed, Q S (1 July 2005). "Forum for planned Chittagong's search for its conservation -I". The Daily Star. Dhaka. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- "Chittagong Port Authority - Banglapedia". En.banglapedia.org. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- "The Bay of Bengal: Rise and Decline of a South Asian Region". YouTube. 16 June 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- http://www.mccibd.org/ebooks/2014/chap-01/mcci_chapter_01.pdf

- L.S.S. O Malley (1999). Bengal District Gazetteer : Darjeeling. Concept Publishing Company. p. 122. ISBN 978-81-7268-018-3.

- https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/30f0/3c45a7353c581c40ac39dbe4ee88621304a2.pdf

- Huddleston, George (1906). History of the East Indian Railway. Calcutta: Thacker, Spink & Company.

- Mukherjee, Hena (1995). The Early History of the East Indian Railway 1845–1879. Calcutta: Firma KLM. ISBN 81-7102-003-8.

- "Railway - Banglapedia". En.banglapedia.org. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- St. John, Ian (2011). The Making of the Raj: India under the East India Company. ABC-CLIO. pp. 83–84. ISBN 9780313097362. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- Gupta, Das (2011). Science and Modern India: An Institutional History, c.1784-1947: Project of History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization, Volume XV, Part 4. Pearson Education India. pp. 454–456. ISBN 9788131753750.

- "Eastern Bengal and Assam - Banglapedia". En.banglapedia.org. 5 May 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- "The legend behind Goalondo Steamer Chicken - Times of India". Timesofindia.indiatimes.com. 24 November 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- https://www.thedailystar.net/star-weekend/bangladeshs-first-balloonist-1301611

- https://www.laweekly.com/the-mystery-of-mrs-van-tassel-the-first-woman-to-parachute-over-l-a/

- "Air Routes in India". Flight Global. 15 April 1920. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- "Bengal Flying Club Opened". Flight Global. 7 March 1929. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- "State of Air Transport in the British Empire". Flight Global. 29 August 1930. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- "Global Networks Before Globalisation: Imperial Airways and the Development of Long-Haul Air Route". Globalization and World Cities Research Network. 5 December 2007. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- "1930 Histoire d'Air Orient". Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- "Amsterdam- Batavia Flight". Flight Global. 20 November 1924. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- "気になる薄毛の事". nscbiairport.org. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- "Amelia Earhart's Circumnavigation Attempt". Tripline.net. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- Raugh, Harold (2004). The Victorians at War, 1815-1914: An Encyclopedia of British Military History. ABC-CLIO Ltd. ISBN 978-1576079256.

- William Dalrymple (10 September 2019). The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 308. ISBN 978-1-4088-6440-1.

- Maya Oppenheim @mayaoppenheim (21 March 2017). "'Winston Churchill is no better than Adolf Hitler,' says Indian politician Dr Shashi Tharoor". The Independent. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Michael Safi in Delhi. "Churchill's policies contributed to 1943 Bengal famine – study | World news". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- "The Bengali Famine - The International Churchill Society". Winstonchurchill.org. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Olson, James S.; Shadle, Robert S., eds. (1996). "Bentinck, Lord William Cavendish". Historical Dictionary of the British Empire. 1. Greenwood Press. p. 131. ISBN 0-313-29366-X.

- "Newspapers and Periodicals - Banglapedia". En.banglapedia.org. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- "Radio - Banglapedia". En.banglapedia.org. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Richard Dixon Oldham (1899). Report of the Great Earthquake of 12th June, 1897. Office of the Geological survey. p. 20.

- The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British and Foreign India, China, and Australia. Parbury, Allen, and Co. 1834. p. 1.

- "Who's Who of Victorian Cinema - Hiralal Sen". victorian-cinema.net.

- "The Liberation Struggles of a Country and a Festival". dhakafilmfestival.org. Dhaka Film Festival. Archived from the original on 11 January 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- Raju, Zakir (2015). Bangladesh Cinema and National Identity: In Search of the Modern. London: Routledge. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-415-46544-1.

- "Dhaka Nawab Family and Film". nawabbari.com. Nawab Bari. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- "Did you know? First Pakistani silent movie makes it to international film fests". tribune.com.pk. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Ramna_Racecourse

- Ritu Birla (14 January 2009). Stages of Capital: Law, Culture, and Market Governance in Late Colonial India. Duke University Press. p. 189. ISBN 0-8223-9247-X.

- Nitish Sengupta (2001). History of the Bengali-speaking People. UBS Publishers' Distributors. p. 211. ISBN 978-81-7476-355-6.

The Bengal Renaissance can be said to have started with Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1775-1833) and ended with Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941).

- Kopf, David (December 1994). "Amiya P. Sen. Hindu Revivalism in Bengal 1872". American Historical Review (Book review). 99 (5): 1741–1742. JSTOR 2168519.

Works cited

![]()

- C. A. Bayly Indian Society and the Making of the British Empire (Cambridge) 1988

- C. E. Buckland Bengal under the Lieutenant-Governors (London) 1901

- Sir James Bourdillon, The Partition of Bengal (London: Society of Arts) 1905

- Susil Chaudhury From Prosperity to Decline. Eighteenth Century Bengal (Delhi) 1995

- Sir William Wilson Hunter, Annals of Rural Bengal (London) 1868, and Odisha (London) 1872

- Imperial Gazetteer of India. Volume 2: The Indian Empire, Historical. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1909.

- P.J. Marshall Bengal, the British Bridgehead 1740–1828 (Cambridge) 1987

- Ray, Indrajit Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757–1857) (Routledge) 2011

- John R. McLane Land and Local Kingship in eighteenth-century Bengal (Cambridge) 1993

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bengal Presidency. |