Aru Islands Regency

The Aru Islands Regency (Indonesian: Kabupaten Kepulauan Aru) are a group of about ninety-five low-lying islands in the Maluku province of eastern Indonesia. They also form a regency of Maluku, with a land area of 8,152.42 square kilometres (3,147.67 square miles). At the 2011 Census the Regency had a population of 84,138;[1] the latest official estimate (as of January 2014) was 93,722.

Aru Islands Regency Kabupaten Kepulauan Aru | |

|---|---|

Seal | |

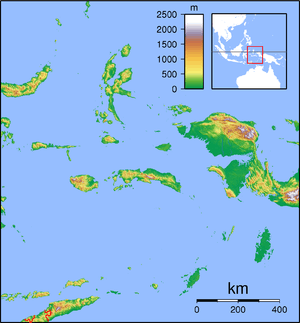

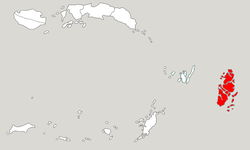

Map of the Aru Islands | |

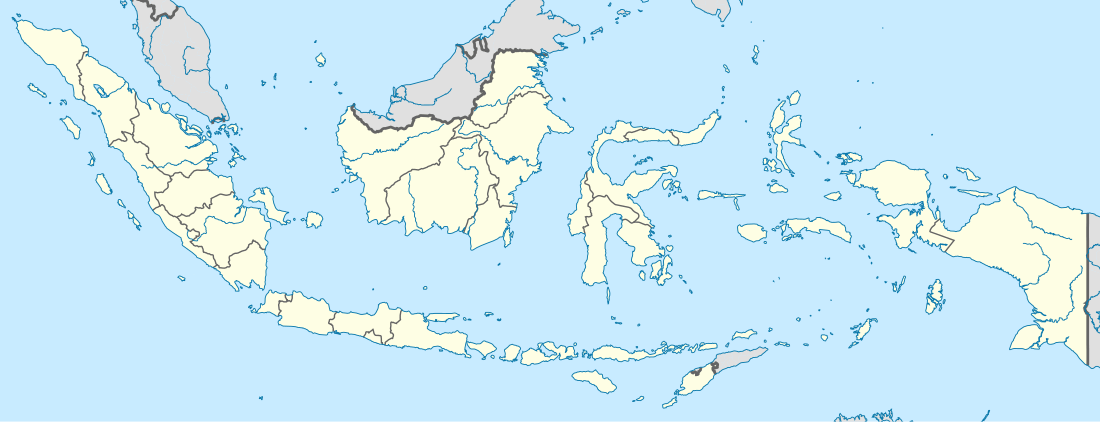

Location within Maluku | |

| Coordinates: 6°10′S 134°30′E | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| Capital | Dobo |

| Government | |

| • Regent | Johan Gonga |

| • Vice Regent | Muin Sugalrey |

| Area | |

| • Total | 8,152.42 km2 (3,147.67 sq mi) |

| Population (2014) | |

| • Total | 93,722 |

| • Density | 11/km2 (30/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+9 (IEST) |

| Area code | (+62) 917 |

| Website | keparukab |

Administration

The regency is divided into seven districts (kecamatan), tabulated below with their areas (in km2) and their 2010 Census populations.

| Name | English name | Area in km2 | Population Census 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aru Utara | North Aru | 1,118.2 | 11,529 |

| Pulau-Pulau Aru | (Northwest Aru) | 973.0 | 36,604 |

| Aru Tengah | Central Aru | 2,116.4 | 13,196 |

| Aru Tengah Timur | East Central Aru | 1,006.1 | 4,315 |

| Aru Tengah Selatan | South Central Aru | 449.3 | 5,086 |

| Aru Selatan | South Aru | 1,386.8 | 8,694 |

| Aru Selatan Timur | Southeast Aru | 1,082.4 | 4,714 |

Geography

The islands are the easternmost in Maluku province, and are located in the Arafura Sea southwest of New Guinea and north of Australia. The total area of the islands is 8,152.42 km2 (3,147 sq mi). The largest island is Tanahbesar (also called Wokam); Dobo, the chief port of the islands, is on Wamar, just off Tanahbesar. The other five main islands are Kola, Kobroor, Maikoor, Koba, and Trangan.[2] The main islands rise to low hills, and are separated by meandering channels. Geologically, the group is part of the Australian continent, along with New Guinea, Tanimbar, Tasmania, Waigeo, and Raja Ampat on the Australian Plate.

Aru is covered by a mix of tropical moist broadleaf forests, savanna, and mangroves. The Islands lie on the Australia-New Guinea continental shelf, and were connected to Australia and New Guinea by land when sea levels were lower during the ice ages. The flora and fauna of Aru are part of the Australasian realm, and closely related to that of New Guinea. Aru is part, together with much of western New Guinea, of the Vogelkop-Aru lowland rain forests terrestrial ecoregion.

As part of the political and administrative decentralization of Indonesia since Suharto stepped down in 1998, the Aru Islands are now a separate residency (kabupaten), headquartered at Dobo, split off from the residency of Central Maluku.

Economy

Pearl farming provides a major source of income for the islands. The Aru pearl industry has been criticized in national media for allegedly maintaining exploitative debt structures that bind the local men who dive for pearls to outside boat owners and traders in an unequal relationship.[3]

Other export products include sago, coconuts, tobacco, mother of pearl, trepang (an edible sea cucumber, which is dried and cured), tortoiseshell, and bird-of-paradise plumes.

In November 2011, the Government of Indonesia awarded two oil-and-gas production-sharing contracts (PSC) about two hundred kilometres (124 mi) west of the Aru Islands to BP. The two adjacent offshore exploration PSCs, West Aru I and II, cover an area of about 16,400 square kilometres (6,300 square miles) with water depths ranging from 200 to 2,500 metres (660 to 8,200 feet). BP plans to acquire seismic data over the two blocks.[4][5]

History

The Aru Islands have a long history as a part of extensive trading networks throughout what is now eastern Indonesia. Precolonial links were especially strong to the Banda Islands, and Bugis and Makasarese traders also visited regularly. The traditional society was not pronounced hierarchical, being based on lineage-based clans where the members shared duties of hospitality and cooperation. These island communities were divided into two ritual bonds called Ursia and Urlima, a socio-political system found in many parts of Maluku. Such alliances were connected to pre-European trade networks.[6]

The islands were sighted and also possibly visited by some Portuguese navigators, such as Martim Afonso de Melo, in 1522-24, who sighted the islands and wintered on a nearby island or of the Aru archipelago itself, and possibly by Gomes de Sequeira, in 1526, as is pointed out in the cartography of the time.[7] The Spanish navigator Álvaro de Saavedra sighted the islands on 12 June 1528, when trying to return from Tidore to New Spain.[8]

The islands were colonized by the Dutch, beginning with a contract with the west coast villages in 1623, though initially the Dutch East India Company (VOC) was one of several trading groups in the area, with limited influence over the islands' internal affairs. Aru was monitored by the VOC establishment in the Banda Islands, and yielded a variety of products including trepang, birds-of-paradise, parrots, pearls, sago, turtle-shell, and slaves. A Dutch post was established on Wokam Island in 1659, and a small fort was subsequently constructed there. Islam as well as Reformed Protestantism began to make small numbers of converts in the 1650s. Discontent with the commercial monopolies imposed by the VOC came to a boiling point in the late 18th century. The anti-Dutch rebellion of the Tidore prince Nuku (d. 1805), which engulfed much of Maluku, also affected Aru. The Muslim population of Ujir Island accepted Nuku's brother Jou Mangofa as their king, exterminated the Dutch garrison in 1787, and were able to dominate large parts of the islands. After several failed attempts, the Dutch of Banda managed to suppress the rebels in 1791.[9] However, they soon ran into new trouble with the coastal populations in the east, and their control of Aru affairs was disrupted by British intervention in the East Indies after 1795.

After being left to its own devices for many years, Aru was again visited in 1824 by the Dutch naval officer A.J. Bik, who concluded a number of agreements with local chiefs.[10] In 1857 the famous naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace visited the islands. His visit later made him realize that the Aru Islands must have been connected by a land bridge to mainland New Guinea during the ice age.[11] In the nineteenth century, Dobo, Aru's largest town, temporarily became an important regional trading center, serving as a meeting point for Dutch, Makasarese, Chinese, and other traders. The period from the 1880s to 1917 saw a backlash against this outside influence, by a spiritually-based movement among local residents to rid the islands of outsiders.

Demographics

The islands had a population of 84,138 at the 2010 Census.[1] Most indigenous islanders are of mixed Austronesian and Papuan descent. Fourteen languages - Barakai, Batuley, Dobel, Karey, Koba, Kola, Kompane, Lola, Lorang, Manombai, Mariri, East Tarangan, West Tarangan, and Ujir - are indigenous to Aru. They belong to the Central Malayo-Polynesian languages, and are related to the other languages of Maluku, Nusa Tenggara, and Timor. Ambonese Malay is also spoken on Wamar. All are members of the Austronesian language family.

The population is mostly Christian with a small Muslim minority. Figures cited by Glenn Dolcemascolo for 1993 were approximately 90% Protestant, 6% Catholic, and 4% Muslim.[12] A more recent report from 2007 suggested that the 4% Muslim figure may only relate to the indigenous population and that the actual percentage of Muslims may be significantly higher.[13] Islam is thought to have been introduced to the islands in the late 15th century.[13] However, it only took root in the mid-17th century, primarily in the Ujir-speaking territory on the western side.[14] The Dutch brought Christianity in the 17th and 18th centuries but much of the conversion of the population to Christianity did not take place until the 20th century.[13]

See also

- Islands of Indonesia

- Aru languages

Notes

- Biro Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2011.

- O'Connor, Sue; Spriggs, Matthew; Veth, Peter (2005). "1". The Archaeology of The Aru Islands. Canberra: The Australian National University. p. 2.

- Spyer, Patricia (1997). The eroticism of debt: pearl divers, traders, and sea wives in the Aru Islands, Eastern Indonesia. American Ethnologist 24(3):515-538.

- "Indonesia: Government Awards Two Offshore PSCs to BP". Offshore Energy Today. 21 November 2011.

- "BP clinches key Indonesian deals". The Scotsman. 22 November 2011.

- A. Ross Gordon and Sonny Djonler, "Oral traditions in cryptic song lyrics; Continuous cultural revitalization in Batuley", Wacana 20-3, 2019.

- Kratoska, Paul H. (2001). South East Asia, Colonial History: Imperialism before 1800, Volume 1 de South East Asia, Colonial History. Taylor & Francis. pp. 52–56.

- Brand, Donald D. The Pacific Basin: A History of its Geographical Exploration The American Geographical Society, New York, 1967, p.121

- Hans Hägerdal and Emilie Wellfelt, "Tamalola; Transregional connectivities, Islam, and anti-colonialism on an Indonesian island", Wacana 20-3, 2019.

- A.J. Bik, Dagverhaal eener reis, gedaan in het jaar 1824 tot nadere verkenning der eilanden Kefing, Goram, Groot-, Klein Kei en de Aroe eilanden. Leiden: Sijthoff, 1928.

- Alfred Russel Wallace, The Malay Archipelago, Vol. 2. EBook 2008, Chapter 30-33.

- Dolcemascolo, Glenn (1996). "Foreign Encounters In an Aruese Landscape". Cakalele. The Center for Southeast Asian Studies. 7: 79–92. hdl:10125/4211. ISSN 1053-2285.

- O’Connor (2007), p. 5

- Emilie Wellfelt and Sonny A. Djonler, "Islam in Aru, Indonesia: Oral traditions and Islamisation processes from the early modern period to the present", Indonesia and the Malay World 47 (138), 2019.

References

- S. O’Connor, M. Spriggs and P. Veth, ed. (2007). Terra Australis 22 - The Archaeology of the Aru Islands, Eastern Indonesia. ANU E Press. ISBN 978-1-921313-04-2.

- Hans Hägerdal and Susi Moeimam, eds (2019). Society and history in Central and Southern Maluku, Wacana; Journal of the Humanities of Indonesia Vol. 20, Issue 3.

- Patricia Spyer (2000), The memory of trade: Modernity's entanglements on an eastern Indonesian island. Durham: Duke University Press.

External links

- J.G.F. Riedel (1886). De sluik- en kruisharige rassen tussen Selebes en Papua. The Hague: Nijhoff, p. 244-271.

- Pieter Bleeker (1858). "De Aroe-eilanden, in vroeger tijd en tegenwoordig", Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsch Indië 20:1, p. 257-275.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aru Islands Regency. |