Tyne and Wear Metro

| |

.jpg) Metrocar 4057 at Monument Metro station, one of the network's principal underground stations. | |

Schematic map of Tyne and Wear Metro | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Owner | Nexus |

| Locale | Tyne and Wear |

| Transit type | Rapid transit/light rail |

| Number of lines | 2 |

| Number of stations | 60 |

| Annual ridership |

37.7 million (2016/17)[1] |

| Headquarters | South Gosforth |

| Website | www.nexus.org.uk/metro |

| Operation | |

| Began operation | 11 August 1980 |

| Operator(s) | Nexus |

| Number of vehicles | 90 Metrocars |

| Train length | 27.81 metres (91.2 ft) |

| Technical | |

| System length | 77.5 km (48.2 mi)[2] |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge |

| Electrification | Overhead line (1,500 V DC) |

| Top speed | 50 miles per hour (80 km/h) |

Tyne & Wear Metro | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Tyne and Wear Metro, referred to locally as simply the Metro, is a rapid transit and light rail system in North East England,[3][4] serving Newcastle upon Tyne, Gateshead, South Tyneside, North Tyneside and Sunderland in the Tyne and Wear region. It has been described as the first modern light rail system in the United Kingdom.[5]

The initial network opened between 1980 and 1984, using converted former railway lines, linked with new tunnel infrastructure. Extensions to the original network were opened in 1991 and 2002.[6] In 2016/17 nearly 38 million passenger journeys were made on the network,[1] which spans 77.5 kilometres (48.2 mi) and has two lines with a total of 60 stations, nine of which are underground.[7][8][2] It is the second-largest of the four metro systems in the United Kingdom, after the London Underground; the others being the Docklands Light Railway and the Glasgow Subway.

The system is owned and operated by the local transport authority Nexus. Between 2010 and 2017 it was operated under contract by DB Regio Tyne & Wear Limited, a subsidiary of Arriva UK Trains.[9] On 1 April 2017, this contract ended, and Nexus took over direct operation of the system for a planned period of two years.[10][11]

History

Predecessor

The present system uses much former railway infrastructure, mostly constructed between 1834 and 1882. One of the oldest parts being the Newcastle & North Shields Railway opened in 1839. In 1904, in response to tramway competition which was taking away passengers, the North Eastern Railway (NER) started electrifying parts of their local railway network north of the River Tyne with a 600V DC third-rail system, forming one of the earliest suburban electric networks, known as the Tyneside Electrics. In 1938, the line south of the Tyne between Newcastle and South Shields was also electrified. In the 1960s under British Rail, the decision was made to de-electrify the Tyneside Electric network, and convert it to diesel operation due to falling passenger numbers, and the cost of renewing life expired electrical infrastructure and rolling stock. The Newcastle-South Shields line was de-electrified in 1963, and the north Tyneside routes were de-electrified in 1967.[2][12][13] This was widely viewed as a backward step, as the diesel trains were slower than the electric trains they replaced.[14]

Planning and construction

In the early 1970s, the poor local transport system was identified as one of the main factors holding back the region's economy, and in 1971 a study was commissioned by the recently created Tyneside Passenger Transport Authority (now known as 'Nexus') into how the transport system could be improved; this study recommended reviving the badly run down former Tyneside Electric network by converting it into an electrified rapid transit system, which would include a new underground section to better serve the busy central areas of Newcastle and Gateshead, as it was felt that the existing rail network didn't serve these areas adequately. This new system was intended to be the core of a new integrated transport network, with buses acting as feeders to purpose-built transport interchanges. The plans were approved by the Tyneside Metropolitan Railway Bill which was passed by Parliament in July 1973. Around 70% of the funding for the scheme came from a central government grant, with the remainder coming from local sources.[15][16][17]

.jpg)

Three railway lines, totalling 26 miles (42 km) were to be converted into Metro lines as part of the initial system; the North Tyneside Loop, and the Newcastle-South Shields branch (both of which were formerly part of the Tyneside Electric network) and a short stretch of the freight-only Ponteland branch, between South Gosforth and Bank Foot, which had not seen any passenger traffic since 1929.[18][2][19] The converted railway lines were to be connected by around six miles (10 km) of new infrastructure, which was built both to separate the Metro from the existing rail network, and also to create the new underground routes under Newcastle and Gateshead. Around four miles (6.4 km) of the new infrastructure was in tunnels, while the remainder was either at ground level or elevated. The elevated sections included the Queen Elizabeth II Bridge; a new 350 metre bridge carrying the Metro across the River Tyne, and the 815 metre Byker Viaduct across the Ouseburn Valley, between Byker and Manors stations.[2][15]

Construction work began in October 1974; this involved the construction of the new infrastructure, re-electrifying the routes with overhead line equipment, the upgrading or relocation of existing stations, and the construction of several new stations, some of which were underground. Originally it was intended to be opened in stages between 1979 and 1981,[15] however the first part of the original network opened in August 1980, and the remainder opened in stages until March 1984.[2][19] The final cost of the project in 1984 prices was £265 million (equivalent to £781,700,000 in 2018 prices[20]).[21]

Further extensions

Some extensions to the original system have since been built. A short 3.5-km extension from Bank Foot to Newcastle Airport was opened in 1991, using a further part of the former Ponteland branch.[19][2]

In 2002 an 18.5-km extension was opened from Pelaw to South Hylton via Sunderland. Costing £100 million, this extension used part of the existing Durham Coast Line to Sunderland, but did not take it over; instead the line between Pelaw and Sunderland was adapted to allow a shared service between the Metro and the conventional rail services, becoming the first UK system to implement a form of the Karlsruhe model.[4] Three intermediate stations on the route were rebuilt, and three new ones were added. Within Sunderland, 4.5 km of a former freight line which had been abandoned in 1984 was reused for the route between Sunderland station and South Hylton, becoming the second Metro segment to be built on a disused line.[2][17]

Opening dates

The opening dates of the services and stations are as follows:[2]

| Year | From | To | Via |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11 August 1980 | Tynemouth | Haymarket | Whitley Bay, South Gosforth |

| 10 May 1981 | South Gosforth | Bank Foot | Fawdon |

| 15 November 1981 | Haymarket | Heworth | Monument |

| 14 November 1982 | St James | Tynemouth | Monument, Wallsend and North Shields |

| 24 March 1984 | Heworth | South Shields | Pelaw, Jarrow |

| 15 September 1985 | Kingston Park | ||

| 16 September 1985 | Pelaw | ||

| 19 March 1986 | Palmersville | ||

| 17 November 1991 | Bank Foot | Newcastle Airport | |

| 31 March 2002 | Pelaw | South Hylton | Sunderland |

| 28 April 2002 | Park Lane | ||

| 11 December 2005 | Northumberland Park | ||

| 17 March 2008 | Simonside |

Metric

The Tyne and Wear Metro was the first railway in the UK to operate using the metric system; all its speeds and distances are stated in metric units only.[22]

Integration

When the Metro opened it was intended to form part of an integrated public transport system, with the local bus network reconfigured to act as 'feeders' for the Metro. Metro was intended to cover trunk journeys, while buses were reoriented toward shorter local trips, integrated with the Metro schedule, to bring passengers to and from Metro stations, using unified ticketing. Integration lasted until deregulation of bus routes in 1986. It is however still possible to buy Transfare tickets that combine a Metro and bus journey.[16]

Recent and ongoing developments

'Metro: All Change programme' Phase 1

New ticket machines accepting notes and cards at all stations and barriers at 13 main stations were installed between 2011 and 2014. The modernisation of Haymarket station, funded through private development, was completed on 29 March 2010,[23] and a new station at Simonside opened in March 2008. An upgrade of platforms at Sunderland and the modernisation of several other stations was included in this phase.

Lifts have been replaced at several Metro stations since 2009 as part of the programme. The programme also includes overhauling infrastructure including communications, track and overhead power lines, structures and embankments.

'Metro: All Change programme' Phase 2

Refurbishment of 90 Metro trains and modernisation of 45 stations, a new communications system, overhaul and maintenance of structures such as bridges, tunnels, track and overhead power lines. North Shields station has also been rebuilt. This work started in 2010 and cost £255.3m. Refurbishment of the Metro trains commenced during the summer of 2010, with 4041 being the first one to undergo a nine-month rebuild;[24] this included a new livery and a new interior.

'Metro: All Change programme' Phase 3

Procurement of a new fleet of Metrocar trains, a new signalling system, overhaul and maintenance of structures, track and overhead lines, and further station improvements. This work is scheduled to start in 2019. Funding for this phase has yet to be secured, and the scheme is being criticised due to the fact that the Metro fleet will be almost 40 years old when replacement begins, even though the fleet has an original design life of approximately 30 years. In October 2016 it was announced that Nexus was to submit a bid to the Department for Transport in order to gain funding for new trains.[25][26]

Routes and services

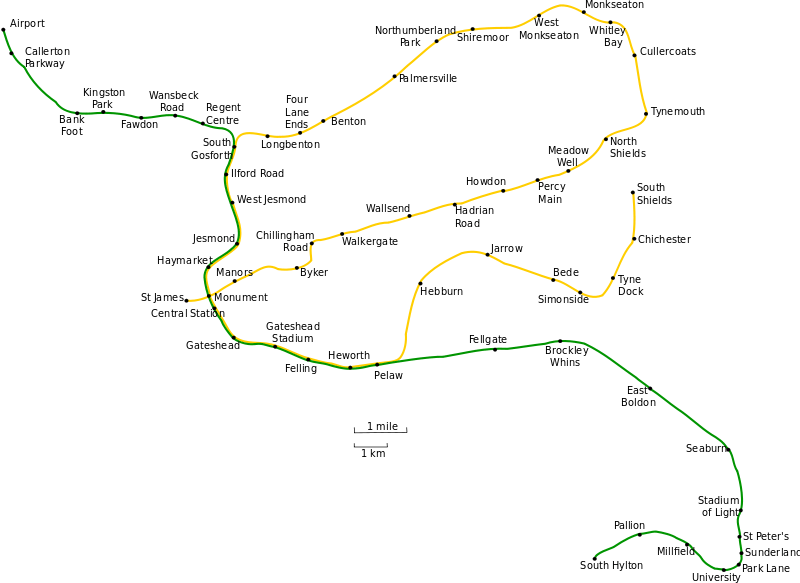

The Metro consists of two lines, the Green Line, which runs between Newcastle Airport and South Hylton (via Newcastle city centre, Gateshead and Sunderland) and the Yellow Line, which runs between St James and South Shields (via North Shields, Tynemouth and Whitley Bay), then looping back on itself and going south (via the city centre, Gateshead and Jarrow).[27]

List of routes: Stations in bold indicate terminating stations

Originally, there was also a Red line between Heworth (later Pelaw) and Benton and a Blue line between St James and North Shields. Additional trains ran on these lines during peak hours to increase the frequency at the busier stations.[21]

Services

Daytime services on each line operate every 12 minutes: on the shared section between South Gosforth and Pelaw this rises to every six minutes. Services operate from around 5:30 until midnight. A full journey on the Green Line between Airport and South Hylton takes 67 minutes. The Yellow Line consists of the North Tyneside Loop, and the branch to South Shields; a full journey around the loop takes 54 minutes, and the full route from St James to South Shields takes 82 minutes.[2] Metro is currently trialling provisions for storage of standard bicycles on services between Callerton Parkway and Jesmond[28].

Regulations

In 2005 the penalty fare for travelling without a valid ticket was increased from £10 to £20.[29] Smoking has been forbidden since opening; this was one of the first comprehensive smoking bans.[30]

Rolling stock

Since the inception of the Tyne and Wear Metro, its rolling stock has remained the same. Its passenger fleet comprises a total of 90 two-car articulated units, known as 'Metrocars', which are numbered 4001–4090: these can operate singly, or in sets of 3 or 4 during empty stock movements, but are normally coupled together in pairs in service and have a maximum speed of 80 km/h (50 mph). The first units to be built were two prototypes, numbered 4001 and 4002, which were delivered for testing in 1975; after modifications they joined the regular fleet in service in 1987. These were followed by 88 production units which were built between 1978 and 1981. The design of the Metrocars was based on the Stadtbahnwagen B, a German light rail vehicle developed in the early 1970s; however they were built in Britain by Metro Cammell at their factory in Birmingham.[31][32][21]

The fleet has been refurbished several times, and several liveries have been used. The original livery used at opening was cadmium yellow and white, in accordance with Tyne and Wear Passenger Transport Executive colours [33]. A mid-life refurbishment of the fleet, carried out in-house, took place between 1995 and 2000, and a new livery was adopted consisting of red, green or blue bodies, with yellow front and rear ends and triangles containing the Metro "M" logo on the doors.[34][31][4] Another full refurbishment of the fleet took place between 2010 and 2015: known as the 'three-quarter-life' refurbishment, the Metrocars were refurbished by Wabtec Rail at its Doncaster facility, with the main goal being to extend their service life until 2025. Each car was stripped down to its frame and built back up again, with the addition of improved disabled access, new door control systems, and renewed interiors, seating and lighting. A new cadmium yellow and black livery was also adopted.[35][34]

| Class | Type | Top speed | Length | Capacity | Number | Fleet Numbers | Routes operated |

Built | Years operated | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mph | km/h | Seated | Standing | ||||||||

| Class 994 | Light Rail Vehicle (LRV) |

50 | 80 | 91 ft 3 in (27.81 m) | 84 | 188 | 90 | 4001–4090 | Green & Yellow Lines |

1975, 1978-1981 |

1980–present |

Proposed new fleet

Nexus have made replacing the ageing fleet of trains, which have been in constant service since 1980, a priority. Due to the advancing age of the fleet, reliability problems have become increasingly common, resulting in breakdowns and cancellations of services. Nexus have stated that, unless a new fleet of trains is available by the end of 2021, widespread cuts will have to be made to peak time services.[36] In 2016 plans were unveiled to secure funding for a new £550 million replacement fleet, with a target for them to be in service by the early 2020s.[37]

In November 2017, Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond announced that the Government would provide £337 million towards the new fleet.[38] The proposed new fleet would consist of 84 trains to replace the existing 90-train fleet, as Nexus believe that the improved reliability of the newer trains would allow them to operate the same service levels with fewer trains. These are proposed to have longitudinal seating instead of the 2+2 bench seating arrangement of the present fleet, and a full width drivers cab as opposed to the smaller driving booth of the existing trains.[36] The proposed new fleet is planned to have dual voltage capability, able to operate on the Metro's existing 1.5 kV DC electrification system and also the 25 kV AC used on the national rail network, to allow for expansion of Metro service into underutilised National Rail lines. Battery technology is also being considered.[39][40][36]

On 17 September 2018, Nexus announced that five companies had been selected to bid for the contract to produce the new fleet. The shortlisted bidders are Bombardier Transportation, CAF, Hitachi, Stadler Rail and a consortium of Australian company Downer EDI Rail and China's CRRC Changchun Railway Vehicles. [41] CAF are offering their Civity platform in their proposal for the fleet. Nexus aim to select a preferred bidder by the end of 2018.

Infrastructure

Stations

The 60 stations on the Metro vary widely in character; some are former railway stations, while others were purpose-built for the Metro. Most of the stations are above ground, but several in central Newcastle and Gateshead are underground, namely Central Station (under Newcastle railway station) Jesmond, Haymarket, Monument, Manors, St James and Gateshead. On the Sunderland extension, Park Lane and Sunderland stations also have underground platforms.[8]

Three of the stations have interchanges with National Rail services: Central, Heworth and Sunderland, which uniquely is the only station in Britain where light and heavy rail services use the same platforms.[8]

All Metro stations are unstaffed, with the exception of the underground stations, which are required to be staffed by law. All stations are equipped with ticket machines, shelters, information displays, next-train indicators and passenger information/emergency help-points.[8]

Metro installed ticket barriers at 13 stations on the network during a modernisation programme in 2013–2014, while the remaining stations have no fixed ticket controls. Despite this, the Tyne and Wear Metro has the third-highest level of passenger income per year (£45.2 million in 2013/2014) of the eight light rail systems in England.[42] Checks are made by roving patrols of inspectors. Ticket machines that accept coins, notes and credit/debit cards were introduced during the modernisation programme.

Metro pioneered the playing of classical music in some of its stations to deter vandalism. In 1998 Frederick Delius's Incidental Music to Hassan was chosen by Metro to be played over its public address system as a deterrent to vandals. The Director General of Nexus was quoted as saying: "The aim is not to soothe but to provide a background of music that people who we are aiming at don't actually like and so they move away. It's been pretty successful." In 2005 the London Underground began to follow Metro's example.[43]

Artwork

Many stations throughout the system feature commissioned works by various artists.[44] Examples include the following:

- A large-scale public artwork by Nayan Kulkarni, Nocturne, consisting of a moving kaleidoscope of light travelling along the Queen Elizabeth II Bridge, which carries the Metro between Newcastle and Gateshead, was inaugurated in April 2007.

- Wallsend station is the only public facility in Britain in which the signage is in Latin. Artist Michael Pinsky was commissioned to create the bilingual signs and a map of Hadrian's Wall in the style of the Metro map to commemorate the area's Roman heritage and its location near the Segedunum Roman fort at the end of the wall. The project was part of Newcastle and Gateshead's unsuccessful joint bid to become European Capital of Culture in 2008.[45]

61st 'station' – Beacon Hill

A mock station, named Beacon Hill, was installed in late 2010 at Beacon Hill School in Wallsend, North Tyneside. It features a building painted like a Metro train, with working passenger doors, standing at a recreated station building, which features a lifelike ticket hall with working ticket machines, a recreated platform area with tactile paving, authentic passenger seating, yellow litter bins and railings and an illuminated Metro "cube" outside. The 'station' was installed at the school in association with Nexus to assist with teaching local children how to travel by Metro, encouraging safe independent travel.[46][47]

Tunnels

.jpg)

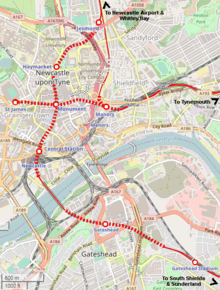

Under Newcastle city centre, two routes run underground at right angles to each other, and intersect at Monument Metro station which has four platforms on two levels. One route, shared by the Yellow and Green lines, runs from north to south. It heads underground at Jesmond Metro station, and runs south via Haymarket, Monument and Central Station before rising above ground to cross the Queen Elizabeth II Bridge over the Tyne. It then enters another tunnel running under Gateshead town centre, serving Gateshead Interchange, before rises above ground again between Gateshead and Gateshead Stadium.[48]

A second underground route, part of the Yellow line, runs from east to west, diving underground from the east under the East Coast Main Line before serving Manors, then Monument (interchanging with the north-south route) and then terminating at St James.[49] Yellow Line trains running from St James pass through Monument station twice, once eastbound through the east-west platforms, and then, after running around the North Tyneside Loop, southbound through the north-south platforms before running to South Shields.[2] Metro therefore, is one of the few rapid-transit system in the world with a "pretzel" configuration, in which a line crosses over itself and trains pass through the same station twice at different platforms. Other examples exist on the current Sofia Metro in Bulgaria [27][4] and the past Vancouver SkyTrain routing in Canada before October 2016.

A short spur line, partly in tunnel, runs from Manors to Jesmond; this line is used for empty stock movements only, and has no passenger service. Before the Metro tunnels were created, it was part of the main line route to Newcastle railway station and connected to the main line at Manors railway station.[48]

The tunnels were constructed in the late 1970s, using mining techniques, and were constructed as single-track tubes with a diameter of 4.75 metres.[2] The tunnels under Newcastle were mechanically bored through boulder clay and lined with cast iron or concrete segments. The tunnel under Gateshead was bored through sandstone and excavated coal seams. Old coal mine workings, some of which dated from the Middle Ages, had to be filled in before the tunnelling began.[15]

Distances

Distances on the system are measured from a datum point at South Gosforth. The system is metric, with distances in kilometres to the nearest metre. Lines are designated In and Out. The In line is from St James to South Shields via the inside of the loop (Yellow Line); the Out line is the opposite. By extension the In line is from Airport to South Gosforth, and from Pelaw to Sunderland and South Hylton. Distance plates are mounted on all overhead line structures. Different distances are normally quoted for stations, depending on whether the direction of travel is In or Out. Distances increase from the datum in all directions.[50]

The part of the Sunderland extension owned by Network Rail is dual-marked in metric units and the miles and chains system used by mainline trains. The boundary between the two systems is close to Pelaw Metro Junction.[51] The closest adjacent stations are St Peter's and Sunderland; the furthest apart Pelaw and Fellgate.

Electrification

The Tyne and Wear Metro is electrified with overhead lines at 1,500 V DC. It is now the only rail network in Britain to use this system.[4][52] Nexus have stated that their long term ambition is to convert the electrification of the Sunderland line, which is shared with main line trains, to the Network Rail standard of 25kv AC, which would require a new fleet of dual voltage trains.[39][40]

Control centre

The Metro's control centre is based at South Gosforth, in a building alongside South Gosforth Metro station. The centre is responsible for operating the network's signalling, and electrical supply, and communicating with train drivers and other staff via two-way radio equipment.[15] The original equipment at the centre was replaced in 2007[4] and the Metro control room was refitted in 2018.[53]

.jpg)

Depot

The depot for the Metro is also based at Gosforth, just north of South Gosforth station, at the centre of the triangular fork between the Airport branch and the northern leg of the North Tyneside Loop. It is used for stabling, maintenance and repair of the Metrocar fleet. It can be accessed by trains from either east or west; there is also a depot-avoiding line running from east to west, which is not used in public service.[54]

The depot had originally been opened in 1923 by the London and North Eastern Railway, to house the previous Tyneside Electrics stock, and was then known as the South Gosforth Car Sheds. It was inherited by Metro upon the system's opening.[54]

In 2015, Nexus reportedly were considering either refurbishing the existing depot for long-term use, or moving operations to a new depot at another location, either at Heaton in Newcastle, or Hebburn in South Tyneside.[55]

Usage

In the first full year of operation during 1984/85, the Metro carried 61.1 million passengers, the highest figure it ever achieved. By 1988/89 this had declined to 45.1 million. The decline was attributed to the loss of integration with bus services in 1986, and the general decline in public transport use in the area.[56]

Usage continued to decline during the 1990s, reaching its lowest level of around 33 million passengers during 2000/01. Since the beginning of the 21st Century, usage has risen and stabilised, fluctuating in a range between 35 and 40 million passengers annually. In recent years, usage topped 40 million in 2008/09, 2009/10 and 2015/16.[57]

Branding and identity

The Metro has a distinctive design and corporate identity, to distinguish itself from the decrepit rail system it replaced and to match the livery of the buses then in use. The Calvert typeface was designed specifically for the Metro by Margaret Calvert, and is used on the distinctive black M against a yellow background which is used to denote the Metro on cube signs outside stations, and also on the trains and other signage.[58] After the branding identity of the Metro became somewhat confused in the 1990s and 2000s, Nexus employed the local design agency Gardiner Richardson to revamp it as part of the All Change programme from 2009. The revamp re-emphasised the Calvert typeface on lettering and signage, and simplified the colour scheme on revamped stations signage and trains to either black, white, grey or yellow.[59]

Ownership and operators

Metro is publicly owned, receiving funding from council tax payers and government. Nexus, which owns and manages Metro, contracted out operations and train maintenance as part of a deal with the UK Government to secure modernisation investment and operating subsidy for the system between 2010 and 2021. Nexus continued to set fares, set frequency of services and Metro operating hours. Opponents say this was privatisation by the back door, though some services had already been contracted out, such as cleaning of stations and ticket inspections. On 3 November 2008, Nexus invited potential bidders to declare an interest in a contract to run the operations side of the business on its behalf. The successful bidder was to obtain a seven-year contract commencing on 1 April 2010, with up to an additional two years depending on performance.[60] In February 2009 four bids were shortlisted; DB Regio, MTR Corporation, Serco-Abellio, and an in-house bid by Metro.[61] By October 2009 the shortlist had been reduced to bids from DB Regio and Nexus.[62] In December 2009, DB Regio was named as the preferred bidder.[63] The contract for operating the system was signed on 2 February 2010, and the service was handed over to DB Regio on 1 April 2010.[64]

One of DB Regio's first initiatives was called Metro Dig It and involved the re-painting of stations and deep-cleaning of stations and trains.[65]

On 3 February 2010 the Government confirmed it would award Nexus up to £580 million to modernise and operate the Tyne and Wear Metro. Up to £350 million was to be spent on the 'Metro: All change programme' over the next eleven years. A further £230 million would support running and maintenance costs over the next nine years.[64]

In March 2016 Nexus announced that they did not intend to renew the contract with DB Regio when it expired in 2017, after stating that they were dissatisfied with the operator due to missed performance targets.[66] On 1 April 2017, Nexus took over direct operation of the system for a planned period of two years, until a new operating contract can be agreed. The RMT union, however, has argued that the direct operation should be made permanent, and operation of the system should remain in public ownership.[10][11]

Proposed extensions and suggested improvements

In 2002, Nexus unveiled an expansion plan to extend the system by adding new sections using street running, changing the Metro into a high-end tram system. Nexus argued that this would provide a cost-effective way to introduce rail service to parts of Tyne and Wear the current Metro services did not reach. The plan listed a number of routes, not all of which were to be built as rail lines; transitional bus services were envisioned, and these could be replaced by trams as demand increased. The original Project Orpheus has been abandoned, possibly because of the government's present "value-for-money" policies for public transport. The use of trams in Tyne & Wear is now less likely, with additional public transport schemes being based around the use of buses .

Nexus has struggled to gain funding for improvements to the existing system, so any extensions are simply part of a long-term vision. Below is a list of previously mooted extensions:

- Tyne Dock to East Boldon along a dismantled railway alignment through Whiteleas could easily be added, because two Metro lines are separated by only a short distance (1.61 miles). This would provide a service from South Shields to Sunderland via the Whiteleas area of South Shields. It was originally suggested by the South Tyneside Local Development Framework and reported by a local newspaper, the Shields Gazette, in January 2008. This would probably be the most likely of extensions, because Nexus is also interested in building stabling facilities for Metro trains at South Shields station as part of the reinvigoration programme.

- Washington,[67] either via the disused Leamside line or a new route. Present planning may lead to the Leamside line being opened at least as far as Washington as a conventional rail line for passengers as well as freight, although this could be shared with Metro trains in the same way as the line from Pelaw Junction to Sunderland. In 2009 ATOC suggested reopening the Leamside line as far south as Washington.[68] On 12 July 2010 local MP Sharon Hodgson started an online petition on the website of local radio station Sun FM to get the Metro extended to Washington.[69]

- Blyth and Ashington, running on existing little-used freight lines. Northumberland Park station has been built to provide a link to a potential new rail service to these communities; if opened, it will not be a part of the Metro system.

- A northward extension to Killingworth and Cramlington has been planned since the Metro was on the drawing board, but would require widening of the busy East Coast Main Line to four tracks, which would be expensive, and a new alignment involving street running .

- Extending the Yellow line to the West End of Newcastle (beyond St. James) would have required tunnelling and bridging in rough terrain at considerable expense. The redevelopment of the old Tyne Brewery site immediately west of St. James has effectively removed the possibility of extending the Yellow line, since there are now building foundations in the way .

- Ryhope and Seaham, a proposal drawn up by Tyne and Wear Passenger Authority to use the existing Durham Coast Line south of Sunderland.

See also

References

- 1 2 "Light Rail and Tram Statistics: England 2016/17" (PDF). Department for Transport. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Schwandle, Robert (2015). Tram Atlas, Great Britain & Ireland. pp. 132–137. ISBN 978 3 936573 45 9.

- ↑ "The longer term effects of the Tyne and Wear Metro". TRL. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Tyne & Wear Metro, United Kingdom". Railway-Technology.com. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- ↑ "How Metro was built". Nexus. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ "Tyne and Wear Metro : Routes : Tyne and Wear Metro routes". TheTrams. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ↑ "Light Rail and Tram Statistics: England 2015/16" (PDF). Department for Transport (DfT). 7 June 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Tyne and Wear Metro : Stations". TheTrams. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ↑ "Who is Nexus?". Nexus. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- 1 2 "Tyne and Wear Metro operator contract to end in 2017". BBC news. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- 1 2 "Tyne and Wear Metro to be publicly run by Nexus". BBC News. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ↑ Hoole, K. (1987). The North Eastern Electrics. The Oakwood Press. ISBN 0 85361 358 3.

- ↑ "The Tyneside Electrics". Suburban Electric Railway Association. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ↑ Young, Alan (1999). Suburban Railways of Tyneside. p. 23. ISBN 1-871944-20-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Meet Your Metro" 1978 information booklet produced by Tyne and Wear Passenger Transport Executive.

- 1 2 "Landmarks in urban transport". Nexus. 2015. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- 1 2 "Sunderland". Railway People. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- ↑ TheTrams.co.uk Tyne and Wear Metro : Routes : Airport

- 1 2 3 "The History of Tramways and Evolution of Light Rail". Light Rail Transit Association. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- ↑ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 Young, Alan (1999). Suburban Railways of Tyneside. pp. 90–94. ISBN 1-871944-20-1.

- ↑ "Guide to Travelling on the Tyne & Wear Metro". Railway Correspondence and Travel Society (RCTS). 22 September 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ↑ "Haymarket Metro stations plans". Nexus. Archived from the original on 27 September 2006. Retrieved 20 February 2007.

- ↑ "Metrocar takes to road as £20m refurbishment begins". Nexus. 22 June 2010. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ↑ puntond (10 October 2016). "Nexus". Nexus. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ Meechan, Simon (12 October 2016). "Your chance to help design the new fleet of Metro carriages". nechronicle. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- 1 2 "Newcastle-Upon-Tyne". UrbanRail.net. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ↑ "Bikes on Metro trial". Nexus. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- ↑ "Increase in T&W Metro fares". Nexus. Archived from the original on 27 September 2006. Retrieved 20 February 2007.

- ↑ "How Metro was built". Nexus. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- 1 2 "Tyne and Wear Metro : Trains". TheTrams. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ "Tyne and Wear Metro celebrates its 40th birthday with a special journey". Chronicle Live. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ "290 / UVK 290T - Tyneside Heritage Vehicles". Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- 1 2 "Bringing contracts back in-house". Rail Technology Magazine. Feb–Mar 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ "Company chosen to refurbish Tyne and Wear's 90 Metrocars". prnewswire. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- 1 2 3 Pickering, Graeme. Metro's new fleet receives the green light (December 6–19, 2017 ed.). Rail magazine. pp. 62–67.

- ↑ "£1bn plan to improve the Metro approved by North East transport chiefs". Chronicle Live. 20 July 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ↑ "BUDGET PROVIDES TRANSPORT BOOST FOR TYNE & WEAR". North East Times. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- 1 2 "Metro bosses unveil plans to extend network, including direct link between Sunderland and South Tyneside". Sunderland Echo. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- 1 2 "New trains and expanded network put forward in Tyne and Wear Metro strategy". Global Rail News. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- ↑ "Shortlisted bidders revealed for £360m Tyne and Wear rolling stock deal". www.railtechnologymagazine.com. Retrieved 2018-09-17.

- ↑ "Light Rail Statistics" (PDF). Department for Transport. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ↑ "Symphonies soothe train vandals". BBC News. 30 January 1998. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- ↑ "Commissions". Nexus. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ↑ "Pontis by Michael Pinsky". Nexus. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ↑ "North Tyneside Independent Travel". beaconhill.n-tyneside.sch.uk. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- ↑ "Painting Of Metro Station In Wallsend". Tynemouth Decorators Ltd. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- 1 2 "Tyne and Wear Metro : Routes : Pelaw–Gosforth". TheTrams. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- ↑ "Tyne and Wear Metro : Routes : North Tyneside Loop". TheTrams. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- ↑ Maxey (Ed.), David (1987). Mile by Mile – Rail Mileages of Britain and Ireland. Peter Watts Publishing Limited, Woodchester, UK. ISBN 0-906025-44-3.

- ↑ Jacobs (Ed.), Gerald (2006). Railway Track Diagrams Book 2: Eastern. Trackmaps, Bradford upon Avon. ISBN 0-9549866-2-8.

- ↑ "Are Electric Trains Eco-Friendly?". AZO Clean Tech. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- ↑ "Watch: timelapse video of £12m Metro control room revamp". Nexus. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- 1 2 "Tyne and Wear Metro : Stations : Gosforth depot". TheTrams. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ↑ "Nexus statement about the Gosforth Metro depot delay in full". Chronicle Live. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ↑ "THE LONGER TERM EFFECTS OF THE TYNE AND WEAR METRO" (PDF). Transport Research Laboratory. 1993. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ↑ "Annual Report 2015/16" (PDF). Nexus. p. 19. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ↑ "How the Tyne and Wear Metro was made - we go back 36 years to the very beginning". Chronicle Live. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ↑ "M IS FOR… METRO (CALVERT TYPEFACE AND THE NEXUS TYNE AND WEAR PUBLIC TRANSPORT VISUAL IDENTITY)". THE BEAUTY OF TRANSPORT. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ↑ "Nexus names final two bidders for Metro operations contract". Nexus. 2 October 2009. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ↑ "Foreign bids for Metro contract". BBC News. 2 February 2009. Retrieved 3 February 2009.

- ↑ "Final shortlist for Metro service". BBC News. 3 October 2009. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- ↑ "DB Regio preferred bidder for Tyne & Wear Metro operating contract". Railway Gazette International. 3 December 2009.

- 1 2 "£580 Million Funding Gives Metro a World-Class Future". Nexus. 3 February 2010. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ↑ "Metro Dig It". Archived from the original on 3 April 2010. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- ↑ "Frustrated by Metro delays? You're right to be - report reveals string of missed targets". Chronicle Live. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ↑ "Plans to extend the Tyne and Wear Metro are considered". BBC News. 25 March 2010. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ↑ "Connecting Communities – Expanding Access to the Rail Network" (PDF). London: Association of Train Operating Companies. June 2009. p. 20. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ↑ "Support our petition to bring the Metro line to Washington". Sun FM. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

Further reading

- Kelly, Peter (December 1981 – January 1982). "A line for all Geordies". Rail Enthusiast. EMAP National Publications. pp. 48–51. ISSN 0262-561X. OCLC 49957965.

- Brown, Murray (June 1984). "Metro miracle is complete". Rail Enthusiast. EMAP National Publications. pp. 23–25. ISSN 0262-561X. OCLC 49957965.

- Etherington, Robin (6–19 April 1989). "New liveries for Tyne & Wear Metro". RAIL. No. 93. EMAP National Publications. p. 10. ISSN 0953-4563. OCLC 49953699.

- Haigh, Phil (3–16 December 1997). "Geordie's canny Metro heads for Wearside". RAIL. No. 319. EMAP Apex Publications. pp. 30–34. ISSN 0953-4563. OCLC 49953699.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tyne and Wear Metro. |

Route map: