Durham Coast Line

| Durham Coast Line | |

|---|---|

Looking south eastwards towards Hartlepool along the line as it leaves Seaham, July 2017 | |

| Overview | |

| System | National Rail |

| Status | Operational |

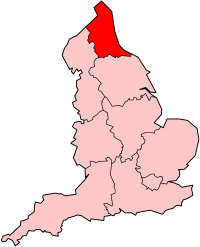

| Locale | North East England |

| Termini |

Newcastle Central Middlesbrough |

| Stations | 10 |

| Operation | |

| Owner | Network Rail |

| Operator(s) |

Northern Grand Central London North Eastern Railway Tyne & Wear Metro |

| Rolling stock |

Northern: Class 142 "Pacer" Class 156 "Super Sprinter" Grand Central Railway: Class 180 London North Eastern Railway: Class 43 "HST" Tyne and Wear Metro: Class 994 "Metrocar" |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) |

| Electrification | 1,500 V DC (Pelaw Junction to Sunderland South Junction) |

The Durham Coast Line (DCL) is the name given to the railway line which links Newcastle upon Tyne with Middlesbrough, via Sunderland and Hartlepool. Most passenger services are operated by Northern and the majority of their services continue on from Newcastle to the MetroCentre and a few to Carlisle. It is an important diversionary route during closures on the East Coast Main Line.

The lines which make up the route were originally constructed by several small independent railway companies (some of which were competing with each other for traffic) which were gradually amalgamated to form the North Eastern Railway who then linked them together to form a coastal through route which was completed in 1905.[1] The North Eastern Railway became part the London and North Eastern Railway at the 1923 Grouping. The DCL comes under the aegis of the Tees Valley Rail Strategy, whose aims are to enhance services in the region. Under that scheme, Phase 1 undertaken on DCL resulted in an hourly service between Newcastle and Hartlepool from 2000; a half-hourly service was later to come into operation. Plans for Phase 2, including opening new stations, has been on hold since the Strategic Rail Authority came into being, when funding for the scheme was brought to a virtual standstill.

The section between the junction just south of Sunderland and Pelaw Junction (just south of Pelaw Metro station) is the only Network Rail route electrified at 1500V DC overhead for use by the Tyne and Wear Metro, which shares this section of the line.

History

Origins

The current route of the DCL has its origins in some of the earliest locomotive operated railways in the North East. The first section of the line to be opened was that constructed by the Clarence Railway (CR). As with many of the early railways, the CR was constructed primarily for the transportation of coal from western and central areas of the Durham Coalfield to the River Tees at North Shore (in Stockton) and Port Clarence and, despite severe financial difficulties, was opened to mineral traffic in 1833[2] but the line did not carry passengers until July 1835 when a service was introduced between Coxhoe and Stockton (Clarence)[3] (which used the modern-day DCL between North Shore Junction and Norton South Junction).

The CR was closely followed by the Hartlepool Dock & Railway (HD&R), a similar concern which opened to mineral traffic on 23 November 1835[1] and passengers four years later. Like the CR, the HD&R intended to link the collieries close to Durham City to the coast (at Hartlepool rather than on the Tees) although the HD&R only reached as far as Haswell due to competition from other railways (see below).[2]

The Durham & Sunderland Railway (D&SR) opened between Sunderland Town Moor and collieries at Hetton and Haswell to both passengers and mineral traffic in 1836[4] and in doing so quickly entered into direct competition with the HD&R for coal traffic from Hawell.[2] The D&SR constructed the first significant north-south section of the DCL to be completed (between Ryhope Grange Junction and Ryhope) and, in conjunction with the HD&R, enabled passengers to travel between Hartlepool and Sunderland for the first time by rail (though such a journey originally required a change of station in Haswell).

The completion of the Brandling Junction Railway (BJR) between Oakwellgate in Gateshead and Wearmouth near Sunderland on 5 September 1839[5] along with the opening of the Stockton & Hartlepool Railway (S&HR) on 10 February 1841 between the Clarence Railway at Billingham-on-Tees and a new terminus near West Hartlepool Docks (as well as a sharp south to east curve at Norton Junction)[2] meant that, with several changes of station, it was possible to travel between the Tees, Wear and Tyne by rail along the coast for the first time. The opening of the High Level Bridge over the River Tyne on 27 September 1849 extended this route though to Newcastle[6] and on 15 May 1852, the official opening of the Stockton extension of the Leeds Northern Railway[7] created a direct link between the Clarence Railway and the rival Stockton & Darlington Railway (S&DR) and thus effectively completed the link between Middlesbrough and Hartlepool.[2]

One year after the LNR reached Stockton, the newly created West Hartlepool Harbour & Railway (see below) began to use the LNR's North Stockton station.[2]

The last of the independent railways that would become part of the DCL to be opened created the first significant 'coastal' section of the line: the Londonderry, Seaham & Sunderland Railway (LS&SR) was constructed, primarily, to enable coal traffic from the Londonderry Railway system to be diverted from Seaham Harbour (which was unable to handle the large volumes of traffic passing through it) to the recently constructed South Dock at Sunderland and ran parallel to the D&SR north of Ryhope. None the less, on 2 July 1855, the LS&SR introduced a passenger service between Seaham and Hendon Burn.[4]

Amalgamations and Creation of a Through Route

The Clarence Railway had struggled financially almost continuously since construction of its first line began and so the more successful S&HR took out a 21-year lease on it in 1844. This was extended to a permanent lease in 1851 before the two companies were amalgamated together and with the West Hartlepool Harbour & Dock Company, on 17 May 1853 to form the West Hartlepool Harbour & Railway (WHH&R).[2]

Meanwhile, the advancement of the Newcastle & Darlington Junction Railway had led it to take over the BJR on 1 September 1844,[8] purchase the D&SR in 1846[9] and, after it was amalgamated with the Great North of England Railway to become the York & Newcastle Railway (Y&NR), it took out a lease on the HD&R. Then, on 22 July 1848, the Y&NR and HD&R both became part of the York, Newcastle & Berwick Railway (YN&BR). Finally, in 1854, the YN&BR, LNR and the York & North Midland Railway were amalgamated to form the North Eastern Railway (NER) which absorbed the WWH&R in 1865.[2] Thus, from 1865, one company was in control of the whole through route between Middlesbrough, Hartlepool, Sunderland and Newcastle though the lines were still largely unconnected.

So as to improve ease of operation along the line, one of the first major additions to the DCL added by the NER was a new curve to link the former LNR to the former S&DR (which had itself been recently been absorbed by the NER) in 1863, thus linking Middlesbrough to the DCL. Then, in 1873, the south to east curve at Norton Junction was realigned so as to ease the severity of its curvature.[2]

In 1877 the NER constructed a new chord at Haswell to link the former HD&R and D&SR lines[10] while, in Hartlepool, a direct link between the former S&HR and HD&R lines running west around the docks was opened to replace the more circuitous link through the docks that had preceded it. Both the ex-S&HR and ex-HD&R termini were replaced by new stations at West Hartlepool and Hartlepool in 1880.[2]

One of the most significant improvements added to the Coast Line by the NER was the creation of a link between Ryhope Grange Junction and Monkwearmouth station which involved the construction of the Monkwearmouth Railway Bridge over the River Wear, Sunderland Central station and tunnels on either side of the station. After the opening of this link, all NER services (as well as those of the LS&SR) were diverted to the new Central Station.[4]

Though these improvements meant that the DCL could now be operated as a through route, any services running between Hartlepool and Sunderland still had to ascend or descend both the 1 in 44 incline at Ryhope Bank and the 1 in 52 incline at Hesleden. To avoid this the NER developed plans to construct a new more direct route that would run along the coast. Construction of the new line between Seaham Colliery station on the LS&SR and a junction with the former HD&R route at Hart Junction was sanctioned in 1894/5[2] and in 1900, the Londonderry Railway agreed to sell their Seaham to Sunderland route to the NER for £387,000.[11]

The new coast line had to cross the denes at Hawthorn, Castle Eden and Crimdon and thus three substantial viaducts, as well as a number of significant embankments and cuttings, were required. Castle Eden Viaduct is one of the most imposing on the route being 141 ft from the ground to rail level and having 10 arches, each with a span of 60 ft. The construction of these viaducts required the opening of a special brickfield and, in the case of Castle Eden Viaduct, the creation of a temporary 800 ft cableway across the valley.[12]

The line was opened on 1 April 1905 with new stations at Blackhall Rocks, Horden and Easington[13] to serve the new villages that had been created to house workers from the coastal collieries which developed along the new line.

The NER became part of the London & North Eastern Railway (LNER) as part of the grouping in 1923.[2] Despite the fact that the LNER was already beginning to experience a decline in traffic due to competition from road vehicles,[4] it did provide some improvements to the line: further stations were opened at Blackhall Colliery on the NER built Seaham to Hart line in 1936[12] and at Seaburn on the ex-BJR line in 1937.[4]

Decline

On 1 January 1948, the LNER became part of the nationalised British Railways (BR) and the Durham Coast Line, along with other lines in the North East, became part of the BR North Eastern Region. By the 1950s, passenger and goods traffic across the country was in decline due to completion from road transport and as a consequence most of the east-west lines from which the DCL had developed began to lose passenger services.[2] These closures included the inland West Hartlepool to Sunderland route through Haswell (the main line between the two towns until 1905) which lost its passenger service on 9 June 1952.[3]

Despite these early closures, the DCL itself was not seriously affected by the closures until it began to lose stations from 1960 onwards, though even the Beeching Report only recommended closure of the remaining three intermediate stations between West Hartlepool and Seaham. These stations were duly closed on 4 May 1964 when stopping passenger services along this section of the line were withdrawn.[14]

Despite this apparent degradation of passenger services, BR replaced the original station at Billingham with a more modern station, closer to the new town centre on 7 November 1966.[15]

Freight traffic on the line continued to thrive while the collieries along the line (and a few short sections of the older east-west lines which had been retained as branches for mineral traffic) were still in operation and, due to the relatively recent development of the coastal collieries, many of them survived until 1980s and early 1990s. Operations at Blackhall Colliery, one of the first that had been served by the DCL to close, ceased on 16 April 1981[16] and between then and the closure of the last colliery of the Durham Coalfield, Wearmouth Colliery, on 24 November 1993,[17] mineral traffic declined.

A halt at Greatham had its service downgraded to a partial service during the early 1980s before being closed completely on the 24 November 1991.[18]

Recent History

The former BR stations on the line at Felling and Pelaw were closed on 5 November 1979 to enable their conversion for use by the Tyne and Wear Metro and were replaced by a new interchange station at Heworth which opened on the same day, with BR services being diverted onto the previously freight only lines between Gateshead and Pelaw Junction.[19] The South Shields branch of the Metro reached Heworth on 15 November 1981 and as a result, Gateshead's BR station was closed just one week later.[20]

In 1996, HM Rail Inspectorate approved plans for the extension of the Metro to Sunderland along tracks shared with main line services on the Durham Coast Line, subject to funding being raised. A grant for £15 million was awarded by the European Regional Development Fund but this was subject to the Tyne and Wear Passenger Transport Executive (Nexus) being able to obtain £35 million of central government funding. This was awarded in 1999 and along with £8 million provided by Nexus and £40 million invested by Railtrack enabled construction to commence in June 2000.

As part of this project, three new Metro only stations were constructed along the DCL at Fellgate, Stadium of Light and St Peters (the latter of which was constructed close to the site of the long-closed Monkwearmouth station) while the existing National Rail stations at Brockley Whins, East Boldon and Seaburn were converted for Metro services. The project also involved the electrification of the DCL between Pelaw Junction and Sunderland South Junction (though the non-standard electrification system used by the Metro meant that the line is the only Network Rail line the UK to use the 1,500V DC overhead system) and an upgrade to signalling on that section of the line.[21]

The Sunderland extension was officially opened by Queen Elizabeth II on 7 May 2002 as part of her Golden Jubilee celebrations.[22]

Route

Passenger Services

Grand Central offer five daily out and back workings between Sunderland and London King's Cross. These trains only call at Hartlepool and Sunderland on the DCL but good connections can be made at Eaglescliffe (for Darlington) and York for onward travel. Sunday sees four train services in both directions.[25]

Northern services over the DCL see trains hourly in both directions between Middlesbrough and Newcastle with some trains starting at Saltburn (on the Tees Valley line) and some starting/finishing at Metro Centre, Hexham or Carlisle.[26]

On 14 December 2015 Virgin Train East Coast (VTEC) introduced a daily return service running along the northern section of the DCL from Sunderland to London King's Cross via Newcastle that the operator has named the 'Spirit of Sunderland'. The outward working departs from Sunderland at 5:40 and calls at Newcastle, Durham , Darlington , York and Peterborough before arriving into King's Cross shortly after 9:00.[27] The return service departs from King's Cross at 20:00 and arrives into Sunderland at 23:22.[28] Following the demise of VTEC, this service (along with all of their other timetabled services) was taken over by the government owned London North Eastern Railway.[29]

Until 2004 a small number of TransPennine Express services operated along the northern section of the DCL as part of their service from Sunderland to Liverpool Lime Street via Newcastle, Durham, Darlington, York, Leeds and Manchester Piccadilly. This service was operated by Northern Spirit and subsequently Arriva Trains Northern from 1998. However, when management of the franchise was taken over by First TransPennine Express, all Transpennine services beyond Newcastle were withdrawn.

Freight Services

Despite the decline in the heavy industry of the North East, the DCL still retains a healthy freight service over the line, including several flows that are generated on the line in addition to several through services. Steel coil is railed into the Tata plant at Hartlepool and pipes are then taken out to Leith and the Far North of Scotland for the North Sea gas and oil industry. Spent nuclear rods are railed out for re-processing at Sellafield from Hartlepool Nuclear Power Station, Cement is delivered to Seaham docks, scrap metal is forwarded from Stockton-On-Tees to Celsa EAF works in Cardiff and Tyne Dock has a trailing connection in both directions at Boldon.[30]

The docks at Sunderland were recently reconnected by Network Rail in anticipation of a return to rail borne traffic - this has yet to come to fruition.[31] Despite the plethora of industrial complexes at Seal Sands, just one customer rails out hydrocarbons from Port Clarence to Cardiff.

Future Developments

Service Enhancements

The new Northern franchise awarded to Arriva Rail North In December 2015 will see service frequencies over the route doubled to half-hourly during the lifetime of the franchise agreement (likely from the December 2017 timetable change).[32] There will also be improvements to rolling stock used on the line (with the removal of Pacer railbuses by 2019 & introduction of refurbished Class 158 DMUs) and more evening services than at present.

New Station

It has been a long held ambition of Durham County Council to reopen a station on the DCL between Seaham and Hartlepool to serve the communities of the south east of the county. The council investigated seven potential sites in the area but it was decided that a site adjacent to the Sea View Industrial Estate in Horden was the most suitable location for the new station.[33] One of the key benefits of this location is its close proximity to the major town of Peterlee which means that, if constructed, it could allow 61,000 residents to benefit from improved access to employment opportunities across the region.

In September 2014 DCC said that they hoped to begin the planning process by the end of the year with the aim of starting construction in 2015 and a potential opening date in spring 2016.[34] However, on 1 June 2015 the MP for Easington, Graham Morris asked a question in parliament regarding the expected date of completion for the new station and was informed that permission to open the station had not yet been sought from the Department for Transport.[35]

In September 2016 DCC announced that the station project was still going ahead although a new preferred site for the station had been identified at South East View in Horden. DCC stated that the project was about to enter stage 4 of the Network Rail GRIP process once the final elements of stage 3 had been completed. The County Council ran a public consultation from 27 September to 20 October 2016 to help them develop the proposal which received over 1200 responses.[36]

In July 2017 it was announced that £4.4 million of funding for the new station had been secured as part of the second round of the Department for Transport's New Stations Fund with the remainder of the estimated £10.5 million cost being provided by the County Council and the North East Combined Authority. The station is expected to open by March 2020 after which point it will be served by more than 20 trains per day.[37]

References

- 1 2 Line Diagrams of the North Eastern Railway: Stockton - Hartlepool - Sunderland - Newcastle. North Eastern Railway Association. 2008. p. 1. ISBN 9781873513682.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Hill, Norman (2001). Teesside Railways A View from the Past. Ian Allan Publishing Ltd. pp. 4, 8, 13, 17, 18, 23, 27, 28, 30, 42, 43, 45, 48, 58, 64, 66 & 67. ISBN 0711028036.

- 1 2 Hoole, K. (1978). North Eastern Railway branch lines since 1925. Ian Allan Ltd. pp. 77 & 114. ISBN 0711008299.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sinclair, Neil T. (1985). Railways of Sunderland. Tyne and Wear County Council Museums. pp. 9, 14, 21, 42, 48, 54 & 62. ISBN 0905974247.

- ↑ Hoole, K. (1965). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: volume 4: The North East. David and Charles. ISBN 0946537313.

- ↑ Addyman, John; Fawcett, Bill (1999). The High Level Bridge and Newcastle Central Station – 150 years across the Tyne. North Eastern Railway Association. ISBN 1873513283.

- ↑ Hoole, K. (1974). North Eastern Album. Littlehampton Book Services Ltd. p. 144. ISBN 9780711005631.

- ↑ Allen, Cecil J (1974) [1964]. The North Eastern Railway (Revised ed.). Ian Allan Ltd. p. 90. ISBN 0711004951.

- ↑ "Disused Stations: Durham Elvet Station". Disused Stations. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- ↑ Hoole, K. (1985). Railways of East Durham. The Dalesman Publishing Company Ltd. p. 8. ISBN 0852068352.

- ↑ Body, Geoffrey (1989). Railways of the Eastern Region. Volume 2: Northern operating area–PSL field guide. Patrick Stephens Limited. p. 150. ISBN 1852600721.

- 1 2 Blackhall Between The Wars - Part One - The Colliery and its influence. Blackhalls Local History Group. 2004. pp. 47 & 49. ISBN 0954149211.

- ↑ British Railways Pre-Grouping Atlas & Gazetteer (6th ed.). Ian Allan Publishing Ltd. 2015. pp. Sheets 27 & 28. ISBN 9780711038172.

- ↑ Waller, Peter (2013). Rail Atlas The Beeching Era. Ian Allan Publishing ltd. pp. 67, 89, 97 & 104. ISBN 9780711035492.

- ↑ "Poster for the New Billingham Station – 1966". Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ↑ "Durham Mining Museum - Blackhall Colliery". Durham Mining Museum. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ↑ "Durham Mining Museum - Wearmouth Colliery". Durham Mining Museum. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ↑ "[ARCHIVED CONTENT] ofclosuredatestopassenge2682.pdf". Archived from the original on 7 June 2009. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ↑ "Disused Stations: Felling Station (3rd site". Disused Stations. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ↑ "Disused Stations: Gateshead East". Disused Stations. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ↑ "Tyne and Wear Metro shares tracks to Sunderland - Railway Gazette". Railway Gazette. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ↑ "Queen swaps Royal Train for the Metro - The Telegraph". The Telegraph. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ↑ "List of dates from 1 January 1985 to 20 January 2006 of last passenger trains at closed BR (or Network Rail stations since privatisation)". Department for Transport Website: Freedom of Information Act responses, February 2006. Department for Transport. 2006. Archived from the original on 2009-06-07. Retrieved 2012-02-06.

- ↑ Poster for New Billingham Station 1966Picture Stockton Archive; Retrieved 2013-12-02

- ↑ "North East and Yorkshire timetable - 17 May to 12 December". www.grandcentralrail.com. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ "Northern Rail Timetable 2" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2015.

- ↑ "Virgin Trains launch Sunderland to London service - BBC News". Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ↑ "Northbound timetable valid from Monday 14 December 2015 to Friday 13 May 2016" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ↑ Calder, Simon (24 June 2018). "East Coast Main Line returns to public owner ship after "total failure of privatisation" | The Independent". The Independent. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ↑ Rawlinson, Mark (2015). Freightmaster 79. Swindon: Freightmaster.

- ↑ "network rail news/2015/apr/april" (PDF).

- ↑ Northern Franchise Improvements - DfTDepartment for Transport; Retrieved 22 August 2016

- ↑ "New Peterlee rail station is still right on track - The Journal". Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ↑ "Plans to build long-awaited Horden station 'progressing' - Rail Technology Magazine". Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ↑ "Railway Stations: Horden:Written question - 584". Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ↑ "Proposal for a new railway station at Horden". Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- ↑ "East Durham to get new railway station after £4.4 million Government funding announcement - Sunderland Echo". Sunderland Echo. Retrieved 29 June 2017.