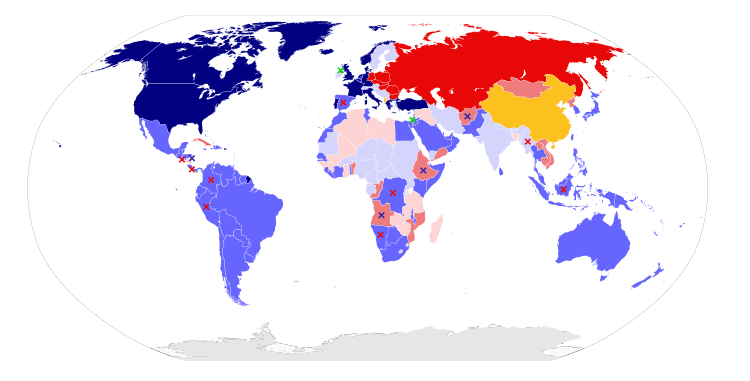

Cold War (1985–1991)

The Cold War period of 1985–1991 began with the rise of Mikhail Gorbachev as leader of the Soviet Union. Gorbachev was a revolutionary leader for the USSR, as he was the first to promote liberalization of the political landscape (Glasnost) and capitalist elements into the economy (Perestroika); prior to this, the USSR had been strictly prohibiting liberal reform and maintained an inefficient centralized economy. The USSR, despite facing massive economic difficulties, was involved in a costly arms race with the United States under President Ronald Reagan. Regardless, the USSR began to crumble as liberal reforms proved difficult to handle and capitalist changes to the centralized economy were badly transitioned and caused major problems. The Cold War came to an end when the last war of Soviet occupation ended in Afghanistan, the Berlin Wall came down in Germany, and a series of mostly peaceful revolutions swept the Soviet Bloc states of eastern Europe in 1989.

Thaw in relations

After the deaths of three successive elderly Soviet leaders since 1982, the Soviet Politburo elected Gorbachev Communist Party General Secretary in March 1985, marking the rise of a new generation of leadership. Under Gorbachev, relatively young reform-oriented technocrats, who had begun their careers in the heyday of "de-Stalinization" under reformist leader Nikita Khrushchev, rapidly consolidated power, providing new momentum for political and economic liberalization, and the impetus for cultivating warmer relations and trade with the West.

On the Western front, President Reagan's administration had taken a hard line against the Soviet Union. Under the Reagan Doctrine, the Reagan administration began providing military support to anti-communist armed movements in Afghanistan, Angola, Nicaragua and elsewhere.

A major breakthrough came in 1985–87, with the successful negotiation of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF). The INF Treaty of December 1987, signed by Reagan and Gorbachev, eliminated all nuclear and conventional missiles, as well as their launchers, with ranges of 500–1,000 kilometres (310–620 mi) (short-range) and 1,000–5,500 kilometres (620–3,420 mi) (intermediate-range). The treaty did not cover sea-launched missiles. By May 1991, after on-site investigations by both sides, 2,700 missiles had been destroyed.[1][2]

The Reagan administration also persuaded the Saudi Arabian oil companies to increase oil production.[3] This led to a three-times drop in the prices of oil, and oil was the main source of Soviet export revenues.[3] Following the USSR's previous large military buildup, President Reagan ordered an enormous peacetime defense buildup of the United States Military; the Soviets did not respond to this by building up their military because the military expenses, in combination with collectivized agriculture in the nation, and inefficient planned manufacturing, would cause a heavy burden for the Soviet economy. It was already stagnant and in a poor state prior to the tenure of Mikhail Gorbachev who, despite significant attempts at reform, was unable to revitalise the economy.[4] In 1985, Reagan and Gorbachev held their first of four "summit" meetings, this one in Geneva, Switzerland. After discussing policy, facts, etc., Reagan invited Gorbachev to go with him to a small house near the beach. The two leaders spoke in that house well over their time limit, but came out with the news that they had planned two more (soon three more) summits.

The second summit took place the following year, in 1986 on October 11, in Reykjavík, Iceland. The meeting was held to pursue discussions about scaling back their intermediate-range ballistic missile arsenals in Europe. The talks came close to achieving an overall breakthrough on nuclear arms control, but ended in failure due to Reagan's proposed Strategic Defense Initiative and Gorbachev's proposed cancellation of it. Nonetheless, cooperation continued to increase and, where it failed, Gorbachev reduced some strategic arms unilaterally.

Fundamental to the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the Gorbachev policy initiatives of Restructuring (Perestroika) and Openness (Glasnost) had ripple effects throughout the Soviet world, including eventually making it impossible to reassert central control over Warsaw Pact member states without resorting to military force.

On June 12, 1987, Reagan challenged Gorbachev to go further with his reforms and democratization by tearing down the Berlin Wall. In a speech at the Brandenburg Gate next to the wall, Reagan stated:

General Secretary Gorbachev, if you seek peace, if you seek prosperity for the Soviet Union, Central and South-East Europe, if you seek liberalization, come here to this gate; Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate. Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall![5]

While the aging communist European leaders kept their states in the grip of "normalization", Gorbachev's reformist policies in the Soviet Union exposed how a once revolutionary Communist Party had become moribund at the very center of the system. Facing declining revenues due to declining oil prices and rising expenditures related to the arms race and the command economy, the Soviet Union was forced during the 1980s to take on significant amounts of debt from the Western banking sector.[6] The growing public disapproval of the Soviet–Afghan War, and the socio-political effects of the Chernobyl accident in Ukraine increased public support for these policies. By the spring of 1989, the USSR had not only experienced lively media debate, but had also held its first multi-candidate elections. For the first time in recent history, the force of liberalization was spreading from West to East.

Revolt spreads through Communist Europe

Grassroots organizations, such as Poland's Solidarity movement, rapidly gained ground with strong popular bases. In February 1989 the Polish government opened talks with opposition, known as the Polish Round Table Agreement, which allowed elections with participation of anti-Communist parties in June 1989. Also in 1989 the Communist government in Hungary started to negotiate organizing of competitive elections which took place in 1990. In Czechoslovakia and East Germany, mass protests unseated entrenched Communist leaders. The Communist regimes in Bulgaria and Romania also crumbled, in the latter case as the result of a violent uprising. Attitudes had changed enough that US Secretary of State James Baker suggested that the American government would not be opposed to Soviet intervention in Romania, on behalf of the opposition, to prevent bloodshed.[7] The tidal wave of change culminated with the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, which symbolized the collapse of European Communist governments and graphically ended the Iron Curtain divide of Europe.

The collapse of the European governments with Gorbachev's tacit consent inadvertently encouraged several Soviet republics to seek greater independence from Moscow's rule. Agitation for independence in the Baltic states led to first Lithuania, and then Estonia and Latvia, declaring their independence. Disaffection in the other republics was met by promises of greater decentralization. More open elections led to the election of candidates opposed to Communist Party rule.

In an attempt to halt the rapid changes to the system, a group of Soviet hard-liners represented by Vice-President Gennady Yanayev launched a coup overthrowing Gorbachev in August 1991. Russian President Boris Yeltsin rallied the people and much of the army against the coup and the effort collapsed. Although restored to power, Gorbachev's authority had been irreparably undermined. In September, the Baltic states were granted independence. On December 1, Ukraine withdrew from the USSR. On December 26, 1991 the USSR officially dissolved, breaking up into fifteen separate nations.

End of the Cold War and the Beginning of a New World Order

After the end of the Revolutions of 1989, Gorbachev and President Bush Sr. met on the neutral island of Malta to discuss the events of the year, the withdrawal of the Soviet military from Eastern Europe, and the future course of their relationship. After their discussions, the two leaders publicly announced they would work together for German reunification, the normalization of relations, the resolution of Third World conflicts, and the promotion of peace and democracy (referred to by President Bush as a "New World Order".)[8]

Between the Malta Summit and the Dissolution of the Soviet Union negotiations on several arms control agreements began, resulting in agreements such as START I and the Chemical Weapons Convention. Additionally, the United States, still believing the Soviet Union would continue to exist in the long term, began to take steps to create a positive long-term relationship.[9]

This new relationship was demonstrated by the joint American-Soviet opposition to Iraq's invasion of Kuwait. The Soviet Union voted in the United Nation's Security Council to authorize the use of military force against its former Middle Eastern ally.[10]

Several conflicts in third world nations (i.e. Cambodia, Angola, Nicaragua) related to the Cold War would come to an end during this era of cooperation, with both the Soviet Union and the United States working together to pressure their respective proxies to make peace with one another. Overall, this detente which accompanied the final twilight of the Cold War would help bring about a relatively more peaceful world.[11]

As a consequence of the Revolutions of 1989 and the adoption of a foreign policy based on non-interference by the Soviet Union, the Warsaw Pact was dissolved and Soviet troops began withdrawing back to the Soviet Union, completing their withdrawal by the mid-1990s.[12][13]

Legacy

There is a fundamental difference in how former communist countries managed during the first quarter of the century after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Countries such as the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Slovakia experienced economic reconstruction, growth and fast integration with EU and NATO while their eastern neighbors usually created hybrids of free market oligarchy system, post-communist corrupted administration and dictatorship. The territory behind the EU and NATO borders gradually to a greater or lesser extent returned to economic and military dependency on Russia.

Russia and the other Soviet successor states have faced a chaotic and harsh transition from a command economy to free market capitalism following the dissolution of the Soviet Union. A large percentage of the population currently lives in poverty. GDP growth also declined, and life expectancy dropped sharply. Living conditions also declined in some other parts of the former Eastern bloc.

In addition, the poverty and desperation of the Russians, Ukrainians and allies of post–Cold War have led to the sale of many advanced Cold War-developed weapons systems, especially very capable modern upgraded versions, around the globe. World-class tanks (T-80/T-84), jet fighters (MiG-29 and Su-27/30/33), surface-to-air missile systems (S-300P, S-300V, 9K332 and Igla) and others have been placed on the market in order to obtain some much-needed cash. This poses a possible problem for western powers in coming decades as they increasingly find hostile countries equipped with weapons which were designed by the Soviets to defeat them. The post–Cold War era saw a period of unprecedented prosperity in the West, especially in the United States, and a wave of democratization throughout Latin America, Africa, and Central, South-East and Eastern Europe.

Sociologist Immanuel Wallerstein expresses a less triumphalist view, arguing that the end of the Cold War is a prelude to the breakdown of Pax Americana. In his essay "Pax Americana is Over," Wallerstein argues, “The collapse of communism in effect signified the collapse of liberalism, removing the only ideological justification behind US hegemony, a justification tacitly supported by liberalism’s ostensible ideological opponent.”[14]

Some historians, including professor of history John Lewis Gaddis, argue that Reagan combined a policy of militancy and operational pragmatism to bring about the most significant improvement in Soviet-American relations since the end of World War II. This bloc, known as the ‘Reagan Victory School’ constitutes a different historiographical perspective to the end of the Cold War.

Space exploration has petered out in both the United States and Russia without the competitive pressure of the space race. Military decorations have become more common, as they were created, and bestowed, by the major powers during the near 50 years of undeclared hostilities.

Timeline of related events

- January 20, 1985 – Ronald Reagan is sworn in for a second term as President of the United States

- March 10, 1985 – General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Konstantin Chernenko dies

- March 11, 1985 – Soviet Politburo member Mikhail Gorbachev becomes the General Secretary of the Communist Party

- March 24, 1985 – Major Arthur D. Nicholson, a US Army Military Intelligence officer is shot to death by a Soviet sentry in East Germany. He is listed as the last US casualty in the Cold War.

- April 26, 1986 - The Chernobyl Disaster

- January 1987 – Gorbachev introduces the policy of demokratizatsiya in the Soviet Union

- March 4, 1987 – In a televised address, Reagan takes full responsibility for the Iran–Contra affair

- June 12, 1987 – "Tear down this wall" speech by Reagan in West Berlin

- December 8, 1987 – The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty is signed in Washington, D.C.

- February 12, 1988 – Hostile rendezvous off coast of Crimea in Black Sea when the Soviet frigate Bezzavetnyy rammed the American missile cruiser USS Yorktown[15]

- February 20, 1988 – The regional soviet of Nagorno-Karabakh in Azerbaijan decides to be part of Armenia, but the Kremlin refuses to do it.[16] The following Nagorno-Karabakh War would be the first of the internal conflicts in the Soviet Union that would become the post-Soviet separatist conflicts

- August 8, 1988 – 8888 Uprising in Burma

- August 17, 1988 – Pakistani president Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq dies

- August 20, 1988 – End of Iran–Iraq War

- September 17, 1988 – Summer Olympics in Seoul, South Korea; first time since 1976 that both Soviet Union and the United States participate; it is also the last Olympic Games for the Soviet Union and its satellite states

- October 5, 1988 – Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet is defeated in a nationwide referendum

- December 21, 1988 - Pan Am Flight 103 bombing

- January 20, 1989 – George H. W. Bush becomes president of the United States

- February 1989 – End of Soviet–Afghan War

- June 3, 1989 – Iranian leader Ayatollah Khomeini dies

- June 4, 1989 – Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 in Beijing, People's Republic of China

- June 4, 1989 – Solidarity's decisive victory in the first partially free parliamentary elections in post-war Poland sparks off a succession of anti-communist Revolutions of 1989 across Central, later South-East and Eastern Europe

- August 14, 1989 – South African president Pieter Willem Botha resigns in reaction to the implementation of Tripartite Accord

- August 23, 1989 – Soviet Politburo member Alexander Yakovlev denounces the secret protocols of the Hitler-Stalin Pact

- August 24, 1989 – Tadeusz Mazowiecki becomes the Prime Minister of Poland forming the first non-communist government in the Communist bloc

- November 9, 1989 – Fall of the Berlin Wall

- December 2–3, 1989 – Malta Summit between Bush and Gorbachev, who said, "I assured the President of the United States that I will never start a hot war against the USA."

- December 25, 1989 – Execution of Nicolae Ceauşescu

- December 29, 1989 – Václav Havel assumes the presidency of Czechoslovakia at the conclusion of Velvet Revolution

- January 13, 1990 – End of Stasi, the secret police of East Germany

- January 22, 1990 - the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, the ruling party of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, collapses during its congress, ending the one party system in the country

- March 15, 1990 – Inauguration of Gorbachev as the first President of the Soviet Union

- April 12, 1990 - The republic of Slovenia within Yugoslavia holds its first multi-party elections

- April 22-23 and May 6-7, 1990 - the republic of Croatia within Yugoslavia holds its first multi-party elections

- April 25, 1990 – Violeta Chamorro is sworn in as president of Nicaragua, ending the Sandinista rule and the Contras insurgency

- May 22, 1990 – South and North Yemens are unified

- July 13, 1990 – The 28th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union announces the end of its monopoly of power

- August 2, 1990 – Beginning of Gulf War

- September 12, 1990 – The Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany is signed in Moscow

- October 3, 1990 – Official reunification of Germany

- November 6, 1990 – Hungary become the first Soviet Bloc country to join the Council of Europe

- November 11, 1990 - The republic of Macedonia within Yugoslavia holds its first multi-party elections

- November 18, 1990 - The republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina within Yugoslavia holds its first multiparty elections

- November 19, 1990 – NATO and Warsaw Pact sign the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe

- November 28, 1990 – Margaret Thatcher falls from power as UK Prime Minister; John Major takes office

- December 9, 1990 - The republic of Montenegro within Yugoslavia holds its first multi-party elections

- December 9-23, 1990 - The republic of Serbia within Yugoslavia holds its first multi-party elections

- December 22, 1990 – Lech Wałęsa becomes president of Poland; Polish government-in-exile ends

- December 23, 1990 - Slovenia holds an independence referendum resulting in a majority of Slovenians voting in favour of Slovenia seeking independence from Yugoslavia

- January 1991 – Money transfers from the Czech budget to Slovakia are stopped, beginning the process that would lead to Velvet Divorce

- February 28, 1991 – End of Gulf War

- May 19, 1991 - Croatia holds an independence referendum resulting in a majority of Croatians voting in favour of Croatia seeking independence from Yugoslavia

- May 29, 1991 – End of Eritrean War of Independence in Ethiopia

- June 27, 1991 – Beginning of the Yugoslav Wars in Slovenia

- June 28, 1991 – The last Comecon council session take place in Budapest; the organization decides to dissolve itself

- July 1, 1991 – End of the Warsaw Pact

- July 10, 1991 – Boris Yeltsin becomes president of Russia

- July 31, 1991 – Ratification of START I treaty between United States and the Soviet Union

- August 19, 1991 – Beginning of the Soviet Union coup d'état attempt

- August 21, 1991 – End of the Soviet Union coup d'état attempt

- August 24, 1991 – Gorbachev resigns from the post of General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

- September 6, 1991 – The Soviet Union recognizes the independence of the Baltic States

- September 8, 1991 - The Republic of Macedonia holds an independence referendum resulting in a majority of Macedonians voting in favour of Macedonia seeking independence from Yugoslavia

- November 6, 1991 – End of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the Soviet KGB

- December 8, 1991 – The Belavezha Accords are signed by the leaders of Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic and Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic, sealing the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the creation of CIS

- December 25, 1991 – Gorbachev resigns as Soviet President and the post is abolished; the red Soviet flag is lowered from the Moscow Kremlin, and in its place the flag of the Russian Federation is raised.

- December 26, 1991 – The Supreme Soviet recognizes the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

- December 31, 1991 – All Soviet Institutions cease operation.

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Lynn E. Davis, "Lessons of the INF Treaty." Foreign Affairs 66.4 (1988): 720–734. in JSTOR

- ↑ CQ Press (2012). Guide to Congress. SAGE. pp. 252–53. ISBN 978-1-4522-3532-5.

- 1 2 Gaidar, Yegor. "Public Expectations and Trust towards the Government: Post-Revolution Stabilization and its Discontents". Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- ↑ Gaidar, Yegor (2007-10-17). Collapse of an Empire: Lessons for Modern Russia (in Russian). Brookings Institution Press. pp. 190–210. ISBN 5-8243-0759-8.

- ↑ "Reagan's 'tear down this wall' speech turns 20". USA Today. 2007-06-12. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ↑ Leebaert, Derek (2002). The Fifty-Year Wound. New York, USA: Little, Brown and Company. p. 595.

- ↑ Garthof, Raymond L. "The Great Transition: American-Soviet Relations and the End of the Cold War" (Washington: Brookings Institution, 1994).

- ↑ "1989: Malta summit ends Cold War". British Broadcasting Corporation. 1989-12-03. Retrieved 2018-03-31.

- ↑ Arjen Molen (2015-09-14), Cold War - Conclusions 1989-1991 - Part 24/24, retrieved 2018-03-31

- ↑ "S/RES/678(1990) - E". undocs.org. Retrieved 2018-03-31.

- ↑ Cohen, Michael (December 15, 2011). "Peace in the Post-Cold War World". The Atlantic. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- ↑ Bohlen, Celestine (February 26, 1991). "Warsaw Pact Agrees to Dissolve Its Military Alliance by March 31". The New York Times. p. 1,10. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- ↑ Marshall, Tyler (April 1, 1993). "Few Russian Troops Remain in Ex-Satellite States: Military: Of an estimated 600,000 in Eastern Europe in the late 1980s, only about 113,000 haven't gone home". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- ↑ Wallerstein, Immanuel. "Pax Americana is Over"

- ↑ (in English) 1988 soviet ramming USS Yorktown CG 48 in black sea (video)

- ↑ Soviet Union Defiance in the Streets, Time, March 07, 1988

References

- Ball, S. J. The Cold War: An International History, 1947–1991 (1998). British perspective

- Beschloss, Michael, and Strobe Talbott. At the Highest Levels:The Inside Story of the End of the Cold War (1993)

- Bialer, Seweryn and Michael Mandelbaum, eds. Gorbachev's Russia and American Foreign Policy (1988)

- Brzezinski, Zbigniew (1983). Power and Principle: Memoirs of the National Security Adviser, 1977–1981. New York City: FSG. ISBN 0374236631.

- Edmonds, Robin. Soviet Foreign Policy: The Brezhnev Years (1983)

- Gaddis, John Lewis. The Cold War: A New History (2005)

- Gaddis, John Lewis. The United States and the End of the Cold War: Implications, Reconsiderations, Provocations (1992)

- Gaddis, John Lewis. Long Peace: Inquiries into the History of the Cold War (1987)

- Gaddis, John Lewis, and Walter LaFeber. America, Russia, and the Cold War, 1945–1992 7th ed. (1993)

- Garthoff, Raymond. The Great Transition:American-Soviet Relations and the End of the Cold War (1994)

- Hogan, Michael ed. The End of the Cold War. Its Meaning and Implications (1992) articles from Diplomatic History online at JSTOR

- Kyvig, David ed. Reagan and the World (1990)

- Leffler, Melvyn P. (2007). For the Soul of Mankind: The United States, the Soviet Union, and the Cold War. New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 0374531420.

- Matlock, Jack F. Autopsy of an Empire (1995) by US ambassador to Moscow

- Mower, A. Glenn Jr. Human Rights and American Foreign Policy: The Carter and Reagan Experiences (1987),

- Powaski, Ronald E. The Cold War: The United States and the Soviet Union, 1917–1991 (1998)

- Shultz, George P. Turmoil and Triumph: My Years as Secretary of State (1993)

- Sivachev, Nikolai and Nikolai Yakolev, Russia and the United States (1979), by Soviet historians

- Smith, Gaddis. Morality, Reason and Power:American Diplomacy in the Carter Years (1986)

- Wilson, James Graham (2014). The Triumph of Improvisation: Gorbachev's Adaptability, Reagan's Engagement, and the End of the Cold War. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801452295.