Sinhalese alphabet

| Sinhalese alphabet සිංහල අක්ෂර මාලාව | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Languages | Sinhalese, Pali, Sanskrit |

Time period | C. 700–present |

Parent systems | |

Sister systems |

Goykanadi Cham alphabet Tigalari alphabet Malayalam script Dhives akuru |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| ISO 15924 |

Sinh, 348 |

Unicode alias | Sinhala |

| |

| Brahmic scripts |

|---|

| The Brahmic script and its descendants |

|

Northern Brahmic

|

The Sinhalese alphabet (Sinhalese: සිංහල අක්ෂර මාලාව) (Siṁhala Akṣara Mālāva) is an alphabet used by the Sinhalese people and most Sri Lankans in Sri Lanka and elsewhere to write the Sinhalese language, as well as the liturgical languages Pali and Sanskrit.[1] The Sinhalese alphabet, one of the Brahmic scripts, is a descendant of the ancient Indian Brahmi script and closely related to the South Indian Grantha script and Kadamba alphabet.[2][1]

The Sinhalese script is an abugida written from left to right. Sinhalese letters are ordered into two sets. The core set of letters forms the śuddha siṃhala alphabet (Pure Sinhalese, ශුද්ධ සිංහල img), which is a subset of the miśra siṃhala alphabet (Mixed Sinhalese, මිශ්ර සිංහල img).

History

The Sinhalese script is a Brahmi derivate, and was imported from Northern India, around the 3rd century BC,[3] but was influenced at various stages by South Indian scripts, manifestly influenced by the early Grantha script.[1]

There have been found potteries in Anuradhapura from the 6th century BC, with lithic inscription dating from 2nd century BC written in Prakrit.[4]

By the 9th century AD, literature written in Sinhalese script had emerged and the script began to be used in other contexts. For instance, the Buddhist literature of the Theravada-Buddhists of Sri Lanka, written in Pali, used the Sinhalese alphabet.

In 1736 the Dutch were the first to print with Sinhalese type on the island. The resulting type followed the features of that of the native Sinhala script practiced on palm leaves. The Dutch created type was monolinear and geometric in fashion with no separation between words in early documents. During the second half of the 19th century, during the Colonial period, a new style of Sinhalese letterforms emerged in opposition to the monolinear and geometric form being high contrast in appearance and having varied thicknesses. This high contrast type gradually replaced the monolinear type as the preferred style which continues to be used in the present day. The high contrast style is still preferred for text typesetting in printed newspapers, books and magazines in Sri Lanka.[5]

Today, the alphabet is used by greater than 16,000,000 people to write the Sinhalese language in very diverse contexts, such as newspapers, TV commercials, government announcements, graffiti, and schoolbooks.

Sinhala is the main language written in this script, but rare instances of Sri Lanka Malay are recorded.

Structure

The Sinhalese script is an abugida written from left to right. It uses consonants as the basic unit for word construction as each consonant has an inherent vowel (/a/), which can be changed with a different vowel stroke. To represent different sounds it is necessary to add vowel strokes, or diacritics called පිලි Pili, that can be used before, after, above or below the base-consonant. Most of the Sinhalese letters are curlicues; straight lines are almost completely absent from the alphabet, and does not have joining characters. This is because Sinhala used to be written on dried palm leaves, which would split along the veins on writing straight lines. This was undesirable, and therefore, the round shapes were preferred. Upper and lower cases do not exist in Sinhalese.[5]

Sinhalese letters are ordered into two sets. The core set of letters forms the śuddha siṃhala alphabet (Pure Sinhalese, ශුද්ධ සිංහල img), which is a subset of the miśra siṃhala alphabet (Mixed Sinhalese, මිශ්ර සිංහල img). This "pure" alphabet contains all the graphemes necessary to write Eḷu (classical Sinhalese) as described in the classical grammar Sidatsan̆garā (1300 AD).[6] This is the reason why this set is also called Eḷu hōdiya ("Eḷu alphabet" එළු හෝඩියimg). The definition of the two sets is thus a historic one. Out of pure coincidence, the phoneme inventory of present-day colloquial Sinhala is such that yet again the śuddha alphabet suffices as a good representation of the sounds.[6] All native phonemes of the Sinhala spoken today can be represented in śuddha, while in order to render special Sanskrit and Pali sounds, one can fall back on miśra siṃhala. This is most notably necessary for the graphemes for the Middle Indic phonemes that the Sinhalese language lost during its history, such as aspirates.[6]

Most phonemes of the Sinhalese language can be represented by a śuddha letter or by a miśra letter, but normally only one of them is considered correct. This one-to-many mapping of phonemes onto graphemes is a frequent source of misspellings.[7]

While a phoneme can be represented by more than one grapheme, each grapheme can be pronounced in only one way. This means that the actual pronunciation of a word is always clear from its orthographic form.

Diacritics

In Sinhala the diacritics are called පිලි pili (vowel strokes). දිග diga means "long" because the vowel is sounded for longer and දෙක deka means "two" because the stroke is doubled when written.

| Using the consonant 'k' + 'vowel' as an example: | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| පිල්ල pilla | Name | Transliteration | Formation | Compound form | ISO 15919 | IPA |

| ් | හල් කිරිම | Hal kirīma | ක් | ක් | k | [k] |

| ◌ | Inherent /a/ (without any pili) | ක් + අ | ක | ka | [kʌ] | |

| ා | ඇලපිල්ල | Ælapilla | ක් + ආ | කා | kā | [kɑː] |

| ැ | ඇදය | Ædaya | ක් + ඇ | කැ | kæ | [kæ] |

| ෑ | දිග ඇදය | Diga ædaya | ක් + ඈ | කෑ | kǣ | [kæː] |

| ි | ඉස්පිල්ල | Ispilla | ක් + ඉ | කි | ki | [ki] |

| ී | දිග ඉස්පිල්ල | Diga ispilla | ක් + ඊ | කී | kī | [kiː] |

| ු | පාපිල්ල | Pāpilla | ක් + උ | කු | ku | [ku], [kɯ] |

| ූ | දිග පාපිල්ල | Diga pāpilla | ක් + ඌ | කූ | kū | [kuː] |

| ෘ | ගැටය සහිත ඇලපිල්ල | Gæṭa sahita ælapilla | ක් + ර් + උ | කෘ | kru | [kru] |

| ෲ | ගැටය සහිත ඇලපිලි දෙක | Gæṭa sahita ælapili deka | ක් + ර් + ඌ | කෲ | krū | [kruː] |

| ෟ | ගයනුකිත්ත | Gayanukitta | Used in conjunction with kombuva for consonants. | |||

| ෳ | දිග ගයනුකිත්ත | Diga gayanukitta | Not in contemporary use | |||

| ෙ | කොම්බුව | Kombuva | ක් + එ | කෙ | ke | [ke] |

| ේ | කොම්බුව සහ හල්කිරීම | Kombuva saha halkirīma | ක් + ඒ | කේ | kē | [keː] |

| ෛ | කොම්බු දෙක | Kombu deka | ක් + ඓ | කෛ | kai | [kʌj] |

| ො | කොම්බුව සහ ඇලපිල්ල | Kombuva saha ælapilla | ක් + ඔ | කො | ko | [ko] |

| ෝ | කොම්බුව සහ හල්ඇලපිල්ල | Kombuva saha halælapilla | ක් + ඕ | කෝ | kō | [koː] |

| ෞ | කොම්බුව සහ ගයනුකිත්ත | Kombuva saha gayanukitta | ක් + ඖ | කෞ | kau | [kʌʋ] |

Non-vocalic diacritics

The anusvara (often called binduva 'zero' ) is represented by one small circle ං (Unicode 0D82),[8] and the visarga (technically part of the miśra alphabet) by two ඃ (Unicode 0D83). The inherent vowel can be removed by a special virama diacritic, the hal kirīma ( ්), which has two shapes depending on which consonant it attaches to. Both are represented in the image on the right side. The first one is the most common one, while the second one is used for letters ending at the top left corner.

Letters

Śuddha set

The śuddha graphemes are the mainstay of the Sinhalese alphabet and are used on an everyday-basis. Every sequence of sounds of the Sinhalese language of today can be represented by these graphemes. Additionally, the śuddha set comprises graphemes for retroflex ⟨ḷ⟩ and ⟨ṇ⟩, which are no longer phonemic in modern Sinhala. These two letters were needed for the representation of Eḷu, but are now obsolete from a purely phonemic view. However, words which historically contain these two phonemes are still often written with the graphemes representing the retroflex sounds.

| Vowels | අ | ආ | ඇ | ඈ | ඉ | ඊ | උ | ඌ | එ | ඒ | ඔ | ඕ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transliteration | a | ā | æ | ǣ | i | ī | u | ū | e | ē | o | ō |

| IPA | [a,ə] | [aː,a] | [æ] | [æː] | [i] | [iː] | [u] | [uː] | [e] | [eː] | [o] | [oː] |

| Consonants | ක | ග | ඟ | ච | ජ | ට | ඩ | ණ | ඬ | ත | ද | ඳ | ප | බ | ම | ඹ | ය | ර | ල | ළ | ව | ස | හ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transliteration | k | g | ňg | c | j | ṭ | ḍ | ṇ | ňḍ | t | d | ňd | p | b | m | m̌b | y | r | l | ḷ | v | s | h |

| IPA | [k] | [g] | [ᵑɡ] | [ʧ] | [ʤ] | [ʈ] | [ɖ] | [n] | [ⁿɖ] | [t] | [d] | [ⁿd] | [p] | [b] | [m] | [ᵐb] | [j] | [r] | [l] | [l] | [ʋ] | [s] | [ɦ] |

Vowels

|

(Click on [show] on the right if you only see boxes below)  | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vowels | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| short | long | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| independent | diacritic | independent | diacritic | ||||||||||||||||||||

| අ | 0D85 | a | [a] | inherent | a | [a, ə] | ආ | 0D86 | ā | [aː] | ා | 0DCF | ā | [aː] | |||||||||

| ඇ | 0D87 | æ/ä | [æ] | ැ | 0DD0 | æ | [æ] | ඈ | 0D88 | ǣ | [æː] | ෑ | 0DD1 | ǣ | [æː] | ||||||||

| ඉ | 0D89 | i | [i] | ි | 0DD2 | i | [i] | ඊ | 0D8A | ī | [iː] | ී | 0DD3 | ī | [iː] | ||||||||

| උ | 0D8B | u | [u] | ු | 0DD4 | u | [u] | ඌ | 0D8C | ū | [uː] | ූ | 0DD6 | ū | [uː] | ||||||||

| එ | 0D91 | e | [e] | ෙ | 0DD9 | e | [e] | ඒ | 0D92 | ē | [eː] | ේ | 0DDA | ē | [eː] | ||||||||

| ඔ | 0D94 | o | [o] | ො | 0DDC | o | [o] | ඕ | 0D95 | ō | [oː] | ෝ | 0DDD | ō | [oː] | ||||||||

| Display this table as an image | |||||||||||||||||||||||

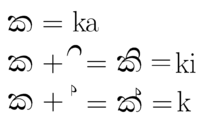

Vowels come in two shapes: independent and diacritic. The independent shape is used when a vowel does not follow a consonant, e.g. at the beginning of a word. The diacritic shape is used when a vowel follows a consonant. Depending on the vowel, the diacritic can attach at several places. The diacritic for ⟨i⟩ attaches above the consonant, the diacritic for ⟨u⟩ attaches below, the diacritic for ⟨ā⟩ follows, while the diacritic for ⟨e⟩ precedes. ⟨o⟩ finally is marked by the combination of preceding ⟨e⟩ and following ⟨ā⟩.

While <a,e,i,o> are regular, the diacritic for ⟨u⟩ takes a different shape according to the consonant it attaches to. The most common one is represented on the image on the right for the consonant ප (p). The k-shape is used for some consonants ending at the lower right corner (ක (k),ග (g), ත(t), but not න(n) or හ(h)). Combinations of ර(r) or ළ(ḷ) with ⟨u⟩ have idiosyncratic shapes.[9]

.svg.png)

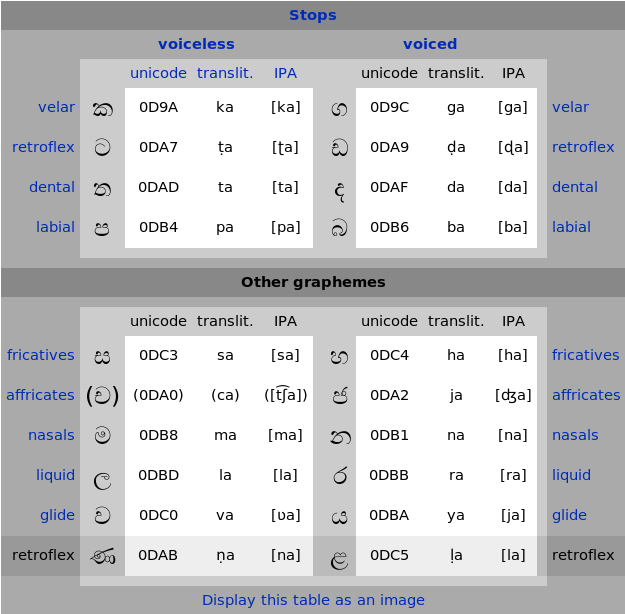

Consonants

|

(Click on [show] on the right if you see only boxes below)

| |||||||||||

| Plosives | |||||||||||

| voiceless | voiced | ||||||||||

| Unicode | translit. | IPA | Unicode | translit. | IPA | ||||||

| velar | ක | 0D9A | ka | [ka] | ග | 0D9C | ga | [ɡa] | velar | ||

| retroflex | ට | 0DA7 | ṭa | [ʈa] | ඩ | 0DA9 | ḍa | [ɖa] | retroflex | ||

| dental | ත | 0DAD | ta | [t̪a] | ද | 0DAF | da | [d̪a] | dental | ||

| labial | ප | 0DB4 | pa | [pa] | බ | 0DB6 | ba | [ba] | labial | ||

| Other letters | |||||||||||

| Unicode | translit. | IPA | Unicode | translit. | IPA | ||||||

| fricatives | ස | 0DC3 | sa | [sa] | හ | 0DC4 | ha | [ha] | fricatives | ||

| affricates | (ච) | (0DA0) | (ca) | ([t͡ʃa]) | ජ | 0DA2 | ja | [d͡ʒa] | affricates | ||

| nasals | ම | 0DB8 | ma | [ma] | න | 0DB1 | na | [na] | nasals | ||

| liquid | ල | 0DBD | la | [la] | ර | 0DBB | ra | [ra] | liquid | ||

| glide | ව | 0DC0 | va | [ʋa] | ය | 0DBA | ya | [ja] | glide | ||

| retroflex | ණ | 0DAB | ṇa | [ɳa] | ළ | 0DC5 | ḷa | [ɭa] | retroflex | ||

| Display this table as an image | |||||||||||

The śuddha alphabet comprises 8 plosives, 2 fricatives, 2 affricates, 2 nasals, 2 liquids and 2 glides. Additionally, there are the two graphemes for the retroflex sounds /ɭ/ and /ɳ/, which are not phonemic in modern Sinhala, but which still form part of the set. These are shaded in the table.

The voiceless affricate (ච [t͡ʃa]) is not included in the śuddha set by purists since it does not occur in the main text of the Sidatsan̆garā. The Sidatsan̆garā does use it in examples though, so this sound did exist in Eḷu. In any case, it is needed for the representation of modern Sinhala.[6]

The basic shapes of these consonants carry an inherent /a/ unless this is replaced by another vowel or removed by the hal kirīma.

Prenasalized consonants

|

(Click on [show] on the right if you see only boxes below)

| ||||||||

| Prenasalized consonants | ||||||||

| nasal | obstruent | prenasalized consonant | Unicode | translit. | IPA | |||

| velar | ඞ | ග | ඟ | 0D9F | n̆ga | [ⁿɡa] | velar | |

| retroflex | ණ | ඩ | ඬ | 0DAC | n̆ḍa | [ⁿɖa] | retroflex | |

| dental | න | ද | ඳ | 0DB3 | n̆da | [ⁿd̪a] | dental | |

| labial | ම | බ | ඹ | 0DB9 | m̆ba | [ᵐba] | labial | |

| Display this table as an image | ||||||||

The prenasalized consonants resemble their plain counterparts. ⟨m̆b⟩ is made up by the left half of ⟨m⟩ and the right half of ⟨b⟩, while the other three are just like the grapheme for the plosive with a little stroke attached to their left.[10] Vowel diacritics attach in the same way as they would to the corresponding plain plosive.

Miśra set

The miśra alphabet is a superset of śuddha. It adds letters for aspirates, retroflexes and sibilants, which are not phonemic in today's Sinhala, but which are necessary to represent non-native words, like loanwords from Sanskrit, Pali or English. The use of the extra letters is mainly a question of prestige. From a purely phonemic point of view, there is no benefit in using them, and they can be replaced by a (sequence of) śuddha letters as follows: For the miśra aspirates, the replacement is the plain śuddha counterpart, for the miśra retroflex liquids the corresponding śuddha coronal liquid,[11] for the sibilants, ⟨s⟩.[12] ඤ (ñ) and ඥ (gn) cannot be represented by śuddha graphemes but are found only in fewer than 10 words each. ෆ fa can be represented by ප pa with a Latin ⟨f⟩ inscribed in the cup.

| Vowels | ඍ | ඎ | ඓ | ඖ | ඏ | ඐ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transliteration | r̥ | r̥̄ | ai | au | l̥ | l̥̄ |

| IPA | [ri,ru] | [riː,ruː] | [ɑj] | [ɑw] | [li] | [liː] |

| Consonants | ඛ | ඝ | ඞ | ඡ | ඣ | ඤ | ඨ | ඪ | ථ | ධ | න | ඵ | භ | ශ | ෂ | ෆ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transliteration | kh | gh | ṅ | ch | jh | ñ | ṭh | ḍh | th | dh | n | ph | bh | ś | ṣ | f |

| IPA | [k] | [g] | [ŋ] | [ʧ] | [ʤ] | [ɲ] | [ʈ] | [ɖ] | [t] | [d] | [n] | [p] | [b] | [ʃ] | [ʃ] | [f] |

Vowels

|

(Click on [show] on the right if you see only boxes below)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vocalic diacritics | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| independent | diacritic | independent | diacritic | ||||||||||||||||||||

| diphthongs | ඓ | 0D93 | ai | [ai] | ෛ | 0DDB | ai | [ai] | ඖ | 0D96 | au | [au] | ෞ | 0DDE | au | [au] | diphthongs | ||||||

| syllabic r | ඍ | 0D8D | ṛ | [ur] | ෘ | 0DD8 | ṛ | [ru, ur] | ඎ | 0D8E | ṝ | [ruː] | ෲ | 0DF2 | ṝ | [ruː, uːr] | syllabic r | ||||||

| syllabic l | ඏ | 0D8F | ḷ | [li] | ෟ | 0DDF | ḷ | [li] | ඐ | 0D90 | ḹ | [liː] | ෳ | 0DF3 | ḹ | [liː] | syllabic l | ||||||

| Display this table as an image | |||||||||||||||||||||||

There are six additional vocalic diacritics in the miśra alphabet. The two diphthongs are quite common, while the "syllabic" ṛ is much rarer, and the "syllabic" ḷ is all but obsolete. The latter are almost exclusively found in loanwords from Sanskrit.[13]

The miśra ⟨ṛ⟩ can be also be written with śuddha ⟨r⟩+⟨u⟩ or ⟨u⟩+⟨r⟩, which corresponds to the actual pronunciation. The miśra syllabic ⟨ḷ⟩ is obsolete, but can be rendered by śuddha ⟨l⟩+⟨i⟩.[14] Miśra ⟨au⟩ is rendered as śuddha ⟨awu⟩, miśra ⟨ai⟩ as śuddha ⟨ayi⟩.

Note that the transliteration of both ළ් and ෟ is ⟨ḷ⟩. This is not very problematic as the second one is extremely scarce.

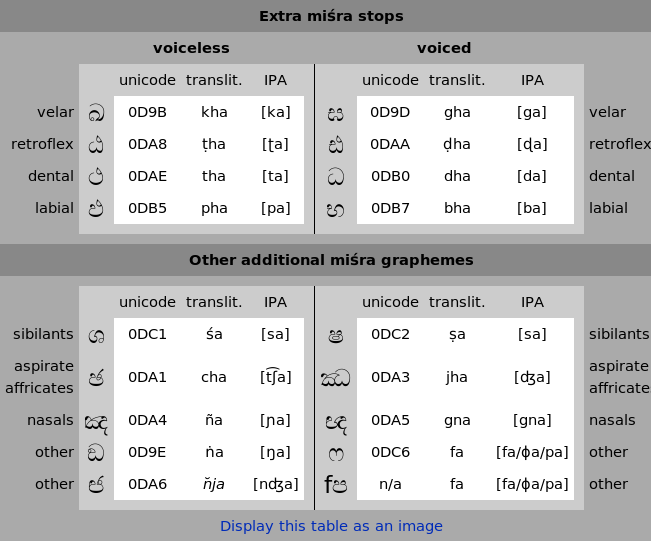

Consonants

|

(Click on [show] on the right if you see only boxes below)

| |||||||||||

| Extra miśra plosives | |||||||||||

| voiceless | voiced | ||||||||||

| Unicode | translit. | IPA | Unicode | translit. | IPA | ||||||

| velar | ඛ | 0D9B | kha | [ka] | ඝ | 0D9D | gha | [ɡa] | velar | ||

| retroflex | ඨ | 0DA8 | ṭha | [ʈa] | ඪ | 0DAA | ḍha | [ɖa] | retroflex | ||

| dental | ථ | 0DAE | tha | [t̪a] | ධ | 0DB0 | dha | [d̪a] | dental | ||

| labial | ඵ | 0DB5 | pha | [pa] | භ | 0DB7 | bha | [ba] | labial | ||

| Other additional miśra graphemes | |||||||||||

| Unicode | translit. | IPA | Unicode | translit. | IPA | ||||||

| sibilants | ශ | 0DC1 | śa | [sa] | ෂ | 0DC2 | ṣa | [sa] | sibilants | ||

| aspirate affricates | ඡ | 0DA1 | cha | [t͡ʃa] | ඣ | 0DA3 | jha | [d͡ʒa] | aspirate affricates | ||

| nasals | ඤ | 0DA4 | ña | [ɲa] | ඥ | 0DA5 | jña | [d͡ʒɲa] | nasals | ||

| other | ඞ | 0D9E | ṅa | [ŋa] | ෆ | 0DC6 | fa | [fa, ɸa, pa] | other | ||

| other | ඦ | 0DA6 | n̆ja[15] | [nd͡ʒa] | fප | n/a | fa | [fa, ɸa, pa] | other | ||

| Display this table as an image | |||||||||||

Consonant conjuncts

Certain combinations of graphemes trigger special ligatures. Special signs exist for an ර (r) following a consonant (inverted arch underneath), a ර (r) preceding a consonant (loop above) and a ය (y) following a consonant (half a ය on the right). [11] [16] [17] Furthermore, very frequent combinations are often written in one stroke, like ddh, kv or kś. If this is the case, the first consonant is not marked with a hal kirīma. [11] [13] [17] The image on the left shows the glyph for śrī, which is composed of the letter ś with a ligature indicating the r below and the vowel ī marked above. Most other conjunct consonants are made with an explicit virama, called al-lakuna or hal kirīma, and the zero-width joiner as shown in the following table, some of which may not display correctly due to limitations of your system. Some of the more common are displayed in the following table. Note that although modern Sinhala sounds are not aspirated, aspiration is marked in the sound where it was historically present to highlight the differences in modern spelling. Also note that all of the combinations are encoded with the al-lakuna (Unicode U+0DCA) first, followed by the zero-width joiner (Unicode U+200D) except for touching letters which have the zero-width joiner (Unicode U+200D) first followed by the al-lakuna (Unicode U+0DCA). Touching letters were used in ancient scriptures but are not used in modern Sinhala. Vowels may be attached to any of the ligatures formed, attaching to the rightmost part of the glyph except for vowels that use the kombuva, where the kombuva is written before the ligature or cluster and the remainder of the vowel, if any, is attached to the rightmost part. In the table below, appending "o" (kombuva saha ælepilla – kombuva with ælepilla) to the cluster "ky" /kja/ only adds a single code point, but adds two vowel strokes, one each to the left and right of the consonant cluster.

| IPA | Letters | Unicode | Combined | Unicode | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /kja/ | ක්ය | U+0D9A U+0DCA U+0DBA | ක්ය | U+0D9A U+0DCA U+200D U+0DBA | yansaya |

| /kjo/ | ක්යො | U+0D9A U+0DCA U+0DBA U+0DCC | ක්යො | U+0D9A U+0DCA U+200D U+0DBA U+0DCC | yansaya |

| /ɡja/ | ග්ය | U+0D9C U+0DCA U+0DBA | ග්ය | U+0D9C U+0DCA U+200D U+0DBA | yansaya |

| /kra/ | ක්ර | U+0D9A U+0DCA U+0DBB | ක්ර | U+0D9A U+0DCA U+200D U+0DBB | rakāransaya |

| /ɡra/ | ග්ර | U+0D9C U+0DCA U+0DBB | ග්ර | U+0D9C U+0DCA U+200D U+0DBB | rakāransaya |

| /rka/ | ර්ක | U+0DBB U+0DCA U+0D9A | ර්ක | U+0DBB U+0DCA U+200D U+0D9A | rēpaya |

| /rɡa/ | ර්ග | U+0DBB U+0DCA U+0D9C | ර්ග | U+0DBB U+0DCA U+200D U+0D9C | rēpaya |

| /kjra/ | ක්ය්ර | U+0D9A U+0DCA U+0DBA U+0DCA U+0DBB | ක්ය්ර | U+0D9A U+0DCA U+200D U+0DBA U+0DCA U+200D U+0DBB | yansaya + rakāransaya |

| /ɡjra/ | ග්ය්ර | U+0D9C U+0DCA U+0DBA U+0DCA U+0DBB | ග්ය්ර | U+0D9C U+0DCA U+200D U+0DBA U+0DCA U+200D U+0DBB | yansaya + rakāransaya |

| /rkja/ | ර්ක්ය | U+0DBB U+0DCA U+0D9A U+0DCA U+0DBA | ර්ක්ය | U+0DBB U+0DCA U+200D U+0D9A U+0DCA U+200D U+0DBA | rēpaya + yansaya |

| /rɡja/ | ර්ග්ය | U+0DBB U+0DCA U+0D9C U+0DCA U+0DBA | ර්ග්ය | U+0DBB U+0DCA U+200D U+0D9C U+0DCA U+200D U+0DBA | rēpaya + yansaya |

| /kva/ | ක්ව | U+0D9A U+0DCA U+0DC0 | ක්ව | U+0D9A U+0DCA U+200D U+0DC0 | conjunct |

| /kʃa/ | ක්ෂ | U+0D9A U+0DCA U+0DC2 | ක්ෂ | U+0D9A U+0DCA U+200D U+0DC2 | conjunct |

| /ɡdʰa/ | ග්ධ | U+0D9C U+0DCA U+0DB0 | ග්ධ | U+0D9C U+0DCA U+200D U+0DB0 | conjunct |

| /ʈʈʰa/ | ට්ඨ | U+0DA7 U+0DCA U+0DA8 | ට්ඨ | U+0DA7 U+0DCA U+200D U+0DA8 | conjunct |

| /t̪t̪ʰa/ | ත්ථ | U+0DAD U+0DCA U+0DAE | ත්ථ | U+0DAD U+0DCA U+200D U+0DAE | conjunct |

| /t̪va/ | ත්ව | U+0DAD U+0DCA U+0DC0 | ත්ව | U+0DAD U+0DCA U+200D U+0DC0 | conjunct |

| /d̪d̪ʰa/ | ද්ධ | U+0DAF U+0DCA U+0DB0 | ද්ධ | U+0DAF U+0DCA U+200D U+0DB0 | conjunct |

| /d̪va/ | ද්ව | U+0DAF U+0DCA U+0DC0 | ද්ව | U+0DAF U+0DCA U+200D U+0DC0 | conjunct |

| /nd̪a/ | න්ද | U+0DB1 U+0DCA U+0DAF | න්ද | U+0DB1 U+0DCA U+200D U+0DAF | conjunct |

| /nd̪ʰa/ | න්ධ | U+0DB1 U+0DCA U+0DB0 | න්ධ | U+0DB1 U+0DCA U+200D U+0DB0 | conjunct |

| /mma/ | ම්ම | U+0DB8 U+0DCA U+0DB8 | ම්ම | U+0DB8 U+200D U+0DCA U+0DB8 | touching |

Letter Names

The letters of the English alphabet have more or less arbitrary names, e.g. em for the letter ⟨m⟩ or bee for the letter ⟨b⟩. The Sinhala śuddha graphemes are named in a uniform way adding -yanna to the sound produced by the letter, including vocalic diacritics.[8][18] The name for the letter අ is thus ayanna, for the letter ආ āyanna, for the letter ක kayanna, for the letter කා kāyanna, for the letter කෙ keyanna and so forth. For letters with hal kirīma, an epenthetic a is added for easier pronunciation: the name for the letter ක් is akyanna. Another naming convention is to use al- before a letter with suppressed vowel, thus alkayanna.

Since the extra miśra letters are phonetically not distinguishable from the śuddha letters, proceeding in the same way would lead to confusion. Names of miśra letters are normally made up of the names of two śuddha letters pronounced as one word. The first one indicates the sound, the second one the shape. For example, the aspirated ඛ (kh) is called bayanu kayanna. kayanna indicates the sound, while bayanu indicates the shape: ඛ (kh) is similar in shape to බ (b) (bayunu = like bayanna). Another method is to qualify the miśra aspirates by mahāprāna (ඛ: mahāprāna kayanna) and the miśra retroflexes by mūrdhaja (ළ: mūrdhaja layanna).

Stroke order

Each Sinhalese letter has a specific stroke order and method of writing.

Numerals and symbols

Sinhalese had special symbols to represent numerals, which were in use until the beginning of the 19th century. This system is now superseded by Hindu–Arabic numeral system.[19][20]

- Sinhala Illakkam (Sinhala Archaic Numbers)

Sinhala Illakkam were used for writing numbers prior to the fall of Kandyan Kingdom in 1815. These digits did not have a zero instead the numbers had signs for 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100, 1000. These digits and numbers can be seen primarily in Royal documents and artefacts.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 100 | 1000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 𑇡 | 𑇢 | 𑇣 | 𑇤 | 𑇥 | 𑇦 | 𑇧 | 𑇨 | 𑇩 | 𑇪 | 𑇫 | 𑇬 | 𑇭 | 𑇮 | 𑇯 | 𑇰 | 𑇱 | 𑇲 | 𑇳 | 𑇴 |

- Sinhala Lith Illakkam (Sinhala Astrological Numbers)

Prior to the fall of Kandyan Kingdom all calculations were carried out using Lith digits. After the fall of the Kandyan Kingdom, Sinhala Lith Illakkam were primarily used for writing horoscopes. However there is evidence that they were used for other purposes such as writing page numbers etc. The tradition of writing degrees and minutes of zodiac signs in horoscopes continued into the 20th century using different versions of Lith Digits. Unlike the Sinhala Illakkam, Sinhala Lith Illakkam included a 0.

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ෦ | ෧ | ෨ | ෩ | ෪ | ෫ | ෬ | ෭ | ෮ | ෯ |

Neither the Sinhala numerals nor U+0DF4 ෴ Sinhalese punctuation kunddaliya is in general use today. The kunddaliya was formerly used as a full stop.[21]

Transliteration

Sinhala transliteration (Sinhala: රෝම අකුරින් ලිවීම rōma akurin livīma, literally "Roman letter writing") can be done in analogy to Devanāgarī transliteration.

Layman's transliterations in Sri Lanka normally follow neither of these. Vowels are transliterated according to English spelling equivalences, which can yield a variety of spellings for a number of phonemes. /iː/ for instance can be ⟨ee⟩, ⟨e⟩, ⟨ea⟩, ⟨i⟩, etc. A transliteration pattern peculiar to Sinhala, and facilitated by the absence of phonemic aspirates, is the use of ⟨th⟩ for the voiceless dental plosive, and the use of ⟨t⟩ for the voiceless retroflex plosive. This is presumably because the retroflex plosive /ʈ/ is perceived the same as the English alveolar plosive /t/, and the Sinhala dental plosive /t̪/ is equated with the English voiceless dental fricative /θ/.[22] Dental and retroflex voiced plosives are always rendered as ⟨d⟩, though, presumably because ⟨dh⟩ is not found as a representation of /ð/ in English orthography.

Relation to other scripts

- Similarities

Sinhala is one of the Brahmic scripts, and thus shares many similarities with other members of the family, such as the Kannada, Malayalam, Telugu, Tamil script and Devanāgarī. As a general example, /a/ is the inherent vowel in all these scripts.[1] Other similarities include the diacritic for ⟨ai⟩, which resembles a doubled ⟨e⟩ in all scripts and the diacritic for ⟨au⟩ which is composed of preceding ⟨e⟩ and following ⟨ḷ⟩.

| Script | ⟨e⟩ | ⟨ai⟩ | ⟨au⟩ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sinhala | ෙ | ෛ | ෞ |

| Malayalam | െ | ൈ | ൌ |

| Tamil | ெ | ை | ௌ |

| Eastern Nagari | ে | ৈ | ৌ |

| Dēvanāgarī | े | ै | ौ |

Likewise, the combination of the diacritics for ⟨e⟩ and ⟨ā⟩ yields ⟨o⟩ in all these scripts.

| Script | ⟨e⟩ | ⟨ā⟩ | ⟨o⟩ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sinhala | ෙ | ා | ො |

| Malayalam | െ | ാ | ൊ |

| Tamil | ெ | ா | ொ |

| Eastern Nagari | ে | া | ো |

| Dēvanāgarī | े | ा | ो |

- Differences

Sinhala alphabet differs from other Indo-Aryan alphabets in that it contains a pair of vowel sounds (U+0DD0 and U+0DD1 in the proposed Unicode Standard) that are unique to it. These are the two vowel sounds that are similar to the two vowel sounds that occur at the beginning of the English words at (ඇ) and ant (ඈ).[23]

Another feature that distinguishes Sinhala from its sister Indo-Aryan languages is the presence of a set of five nasal sounds known as half-nasal or prenasalized stops.

| ඟ | ඦ | ඬ | ඳ | ඹ |

| n̆ga | n̆ja | n̆ḍa | n̆da | n̆ba |

Computer encoding

Generally speaking, Sinhala support is less developed than support for Devanāgarī for instance. A recurring problem is the rendering of diacritics which precede the consonant and diacritic signs which come in different shapes, like the one for ⟨u⟩.

Sinhala does not come built in with Windows XP, unlike Tamil and Hindi. However, all versions of Windows Vista and Windows 10 come with Sinhala support by default, and do not require external fonts to be installed to read Sinhalese script. Nirmala UI is the default Sinhala font in windows 10.

For Mac OS X, Sinhala font and keyboard support can be found at web.nickshanks.com/typography/ and at www.xenotypetech.com/osxSinhala.html.

For Linux, the IBus, and SCIM input methods allow the use Sinhalese script in applications with support for a number of key maps and techniques such as traditional, phonetic and assisted techniques.[24] In addition, newer versions of Android mobile operating system also support both rendering and input of the Sinhala script.

Unicode

Sinhalese script was added to the Unicode Standard in September 1999 with the release of version 3.0. This character allocation has been adopted in Sri Lanka as the Standard SLS1134.

The main Unicode block for Sinhala is U+0D80–U+0DFF. Another block, Sinhala Archaic Numbers, was added to Unicode in version 7.0.0 in June 2014. Its range is U+111E0–U+111FF.

| Sinhala[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+0D8x | ං | ඃ | අ | ආ | ඇ | ඈ | ඉ | ඊ | උ | ඌ | ඍ | ඎ | ඏ | |||

| U+0D9x | ඐ | එ | ඒ | ඓ | ඔ | ඕ | ඖ | ක | ඛ | ග | ඝ | ඞ | ඟ | |||

| U+0DAx | ච | ඡ | ජ | ඣ | ඤ | ඥ | ඦ | ට | ඨ | ඩ | ඪ | ණ | ඬ | ත | ථ | ද |

| U+0DBx | ධ | න | ඳ | ප | ඵ | බ | භ | ම | ඹ | ය | ර | ල | ||||

| U+0DCx | ව | ශ | ෂ | ස | හ | ළ | ෆ | ් | ා | |||||||

| U+0DDx | ැ | ෑ | ි | ී | ු | ූ | ෘ | ෙ | ේ | ෛ | ො | ෝ | ෞ | ෟ | ||

| U+0DEx | ෦ | ෧ | ෨ | ෩ | ෪ | ෫ | ෬ | ෭ | ෮ | ෯ | ||||||

| U+0DFx | ෲ | ෳ | ෴ | |||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

| Sinhala Archaic Numbers[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+111Ex | 𑇡 | 𑇢 | 𑇣 | 𑇤 | 𑇥 | 𑇦 | 𑇧 | 𑇨 | 𑇩 | 𑇪 | 𑇫 | 𑇬 | 𑇭 | 𑇮 | 𑇯 | |

| U+111Fx | 𑇰 | 𑇱 | 𑇲 | 𑇳 | 𑇴 | |||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Daniels (1996), p. 408.

- ↑ Jayarajan, Paul M. (1976-01-01). History of the Evolution of the Sinhala Alphabet. Colombo Apothecaries' Company, Limited.

- ↑ Daniels (1996), p. 379.

- ↑ Ray, Himanshu Prabha (2003-08-14). The Archaeology of Seafaring in Ancient South Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521011099.

- 1 2 "The Sinhala Script". Dalton Maag. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Gair and Paolillo 1997.

- ↑ Matzel (1983) p. 15, 17, 18

- 1 2 Karunatillake (2004), p. xxxii

- ↑ Jayawardena-Moser (2004) p. 11

- ↑ Fairbanks et al. (1968), p. 126

- 1 2 3 Karunatillake (2004), p. xxxi

- ↑ Daniels (1996), p. 410.

- 1 2 Matzel (1983), p. 8

- ↑ Matzel (1983), p. 14

- ↑ This letter is not used anywhere, neither in modern nor ancient Sinhala. Its usefulness is unclear, but it forms part of the standard alphabet <http://unicode.org/reports/tr2.html>.

- ↑ Fairbanks et al. (1968), p. 109

- 1 2 Jayawardena-Moser (2004), p. 12

- ↑ Fairbanks et al. (1968), p. 366

- ↑ "Online edition of Sunday Observer – Business". Sunday Observer. Archived from the original on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 21 September 2008. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Unicode Mail List Archive: Re: Sinhala numerals". Unicode Consortium. Retrieved 21 September 2008. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ Roland Russwurm. "Old Sinhala Numbers and Digits". Sinhala Online. Retrieved 23 September 2008. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ Matzel (1983), p. 16

- ↑ https://www.isoc.org/inet97/proceedings/E1/E1_3.HTM

- ↑ A screenshot showing some of the options

Further reading

- Daniels, Peter T. (1996). "Sinhala alphabet". The World's Writing Systems. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507993-0.

- Fairbanks, G. W.; J. W. Gair; M. W. S. D. Silva (1968). Colloquial Sinhalese (Sinhala). Ithaca, NY: South Asia Programm, Cornell University.

- Gair, J. W.; John C. Paolillo (1997). Sinhala. München, Newcastle: South Asia Programm, Cornell University.

- Geiger, Wilhelm (1995). A Grammar of the Sinhalese Language. New Delhi: AES Reprint.

- Jayawardena-Moser, Premalatha (2004). Grundwortschatz Singhalesisch – Deutsch (3 ed.). Wiesbaden: Harassowitz.

- Karunatillake, W. S. (1992). An Introduction to Spoken Sinhala ([several new editions] ed.). Colombo.

- Matzel, Klaus (1983). Einführung in die singhalesische Sprache. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Image list for readers with font problems

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sinhala script. |

- Scripts (ISO 15924) "Sinhala"

- Sinhala Unicode Characters

- Sinhala Unicode Characters

- Sinhala Unicode Character Code Chart

- Sinhala Archaic Numbers Unicode Character Code Chart

- Complete table of consonant-diacritic-combinations

- Online resources