Chatham Dockyard

| HM Dockyard, Chatham | |

|---|---|

| Chatham, Kent | |

Chatham Dockyard in 1790 (by Nicholas Pocock) | |

Chatham Dockyard (Kent) | |

| Coordinates | 51°23′50″N 00°31′40″E / 51.39722°N 0.52778°E |

| Site information | |

| Operator | Royal Navy |

| Controlled by | The Navy Board (until 1832); the Admiralty (1832-1964). |

| Open to the public | as Chatham Historic Dockyard |

| Other site facilities | Military barracks and fortifications |

| Website | Chatham Historic Dockyard |

| Site history | |

| In use | 1567-1984 |

| Fate | Preserved as a maritime heritage visitor attraction |

| Events | Raid on the Medway, 1667 |

Chatham Dockyard was a Royal Navy Dockyard located on the River Medway in Kent. Established in Chatham in the mid-16th century, the dockyard subsequently expanded into neighbouring Gillingham (at its most extensive, in the early 20th century, two-thirds of the dockyard lay in Gillingham, one-third in Chatham).

It came into existence at the time when, following the Reformation, relations with the Catholic countries of Europe had worsened, leading to a requirement for additional defences. For 414 years Chatham Royal Dockyard provided over 500 ships for the Royal Navy, and was at the forefront of shipbuilding, industrial and architectural technology. At its height, it employed over 10,000 skilled artisans and covered 400 acres (1.6 km²). Chatham dockyard closed in 1984, and 84 acres (340,000 m2) of the Georgian dockyard is now managed as a visitor attraction by the Chatham Historic Dockyard Trust.

Outline history

The Treasurer of the Navy's accounts of the King's Exchequer for the year 1544 identifies Deptford as the Dockyard that carried out all the major repairs to the King's Ships that year. That was soon to change (although Deptford remained a dockyard for over three centuries).

Jillingham water

Chatham's establishment as a naval dockyard was precipitated by the use of the Medway as a safe anchorage by the ships of what was to become (under King Henry VIII) England's permanent Royal Navy. In 1550, a decree was issued to the Lord High Admiral that:

- the Kinges shipps shulde be harborowed [harboured] in Jillingham Water – saving [except] those that be at Portsmouth – to remaigne there till the yere be further spent...

Even prior to this, there is evidence of certain shore facilities being established in the vicinity for the benefit of the King's ships at anchor: there are isolated references from as early as 1509 to the hiring of a storehouse nearby[1] and from 1547 this becomes a fixed item in the Treasurer's annual accounts. (At around the same time a victualling store was also established, in nearby Rochester, to provide the ships and their crews with food.) The storehouse would have furnished ships with such necessary consumables as rope, pulleys, sailcloth and timber; for more specialised repairs and maintenance, however, they would have had to travel to one of the purpose-built royal dockyards (the nearest being those on the Thames: Deptford and Woolwich).

The early dockyard

1567 is generally seen as the date of Chatham's establishment as a Royal Naval Dockyard.[2] In the years that followed the ground was prepared, accommodation was secured and a mast pond was installed. The renowned Tudor shipwright Mathew Baker was appointed to Chatham in 1572 (though he was primarily based at Deptford). Under his supervision the site was developed to include sawpits, workshops, a wharf with a crane and, most significantly, its first dry dock, which opened in 1581. The dockyard received its first royal visit, from Elizabeth I, in 1573. The first ship to be built at the dockyard, HMS Sunne was launched in 1586.[3]

Relocation and consolidation

James I used Chatham dockyard for a meeting in 1606 with Christian IV of Denmark.[4] In 1613, the dockyard moved from its original location (now the gun wharf to the south) to its present site.[3] The growing importance of the dockyard was illustrated with the addition of two new mast ponds, and the granting of additional land on which a dock, storehouse, and various brick and lime kilns were planned. Peter Pett, of the family of shipwrights whose history is closely connected to the Chatham dockyard, became commissioner in 1649.[5]

One of the disadvantages of Chatham (and also of the Thames-side yards) was their relative inaccessibility for ships at sea (including those anchored in The Nore). Therefore, rather than risk being constrained by wind, tide and draught on a journey upriver, ships would seek as often as possible to do running repairs and maintenance while at anchor, and would only travel to the dockyard when necessary. Thus deliveries of victuals, ordnance and other supplies were made by small boats, sailing regularly between Chatham and The Nore.[6]

Sheerness

Seeking to alleviate this less-than-satisfactory situation, the Navy Board explored options for developing a shore facility with direct access from the open water of the Thames Estuary. The escalating Anglo-Dutch wars forced their hand, however: several temporary buildings were hastily erected on Sheerness, at the mouth of the Medway, to enable ships to re-arm, re-victual and (if necessary) be repaired as quickly as possible. In 1665, the Navy Board approved Sheerness as a site for a new dockyard, and building work began; but in 1667 the still-incomplete Sheerness Dockyard was captured by the Dutch Navy and used as the base for a humiliating attack on the English fleet at anchor in the Medway itself. Sheerness remained operational as a royal dockyard until 1959, but it was never considered a major shore establishment and in several respects it operated as a subsidiary yard to Chatham.[7]

Expansion

By the late 17th century Chatham was the largest refitting dockyard, important during the Dutch wars. It was, however, superseded in the following century, first by Portsmouth, then Plymouth, when the main naval enemy became France, and the Western approaches the chief theatre of operations. In addition, the Medway had begun to silt up, making navigation more difficult. Nevertheless, following a visit by the Admiralty Board in 1773, the decision was taken to invest further in Chatham, which developed into a building yard rather than a refitting base.[5] Among many vessels built in this Dockyard and which still exist, are HMS Victory, launched in 1765 – now preserved at Portsmouth Historic Dockyard.[8]

By the year 1770 the establishment had so expanded that, including the gun wharf, it stretched a mile (1.6 km) in length, and included an area of in excess of 95 acres (384,000 m²), possessing four slip ways and four large docks. The officers and men employed in the yard also increased, and by 1798 they numbered 1,664, including 49 officers and clerks and 624 shipwrights. Additionally required were the blockmakers, caulkers, pitch-heaters, blacksmiths, joiners and carpenters, sail makers, riggers, and ropemakers (274), as well as bricklayers, labourers and others.[9]

Mechanisation

_p.039_-_Chatham_-_A_%2B_C_Black_(pub).jpg)

Between 1862 and 1885, the yard underwent another large building programme as the Admiralty adjusted to the new technology of steam-powered ships with metal hulls. Three basins were constructed along St Mary's creek: of 28 acres (110,000 m2), 20 acres (81,000 m2) and 21 acres (85,000 m2). There were four new dry docks. Much of the work was done by convict labour. The construction materials required regenerated the North Kent brick and cement industries. It is estimated that 110 million bricks were used. These basins formed the Victorian Dockyard. Chatham built on average, two new ships each year. HMS Unicorn, (a Leda class frigate), now preserved afloat at Dundee, was launched at Chatham in 1824.[10]

With the 20th century came the submarine. HMS C17 was launched at Chatham in 1908, and during World War I, twelve submarines were built here, but when hostilities ceased, uncompleted boats were scrapped and five years passed before a further ship was launched. In the interwar years, 8 "S" class submarines were built at Chatham but this was a period of decline. During World War II there were 1,360 refits and sixteen launchings.

Last years

The final boats constructed in Chatham were Oberon class submarines – Ocelot was the last vessel built for the Royal Navy, and the final vessel was Okanagan built for the Royal Canadian Navy and launched on 17 September 1966. In 1968, a nuclear submarine refitting complex was built complete with refuelling cranes and health physics building. In spite of this in June 1981, it was announced to Parliament that the dockyard would be run down and closed in 1984.[11]

In the mid-1980s Defence Estates disposed of the former Royal Navy ratings Married Quarters on the nearby Walderslade Estate, which were sold by public auction. These were previously occupied by personnel from the Royal Navy dockyard Chatham, with 110 married quarters being sold. The Georgian site is now a visitor attraction, under the care of the Chatham Historic Dockyard Trust. The Trust is preparing an application for the Dockyard and its Defences to become a World Heritage Site.[12]

Administration of the dockyard

Resident Commissioners of the Navy Board

The Commissioner of Chatham Dockyard held a seat and a vote on the Navy Board in London. The Commissioners were:[13]

- 1631–1647 Phineas Pett[14]

- 1648–1668 Peter Pett[15]

- 1669–1672 John Cox[16]

- 1672–1686 Thomas Middleton[17]

- 1686–1689 Phineas Pett[18]

- 1689–1703 Sir Edward Gregory[18]

- 1703–1714 George St Lo[18]

- 1714–1722 James Lyttleton[18]

- 1722–1736 Thomas Kempthorne[18]

- 1736–1742 Thomas Mathews[18]

- 1742–1754 Charles Brown[18]

- 1754–1755 Arthur Scott[18]

- 1755–1763 Thomas Cooper[18]

- 1763–1771 Thomas Hanway[18]

- 1771–1799 Charles Proby[18]

- 1799–1801 John Hartwell[19]

- 1801–1808 Captain Charles Hope[20]

- 1808–1823 Captain Robert Barlow[21]

- 1823–1829 Captain Charles Cunningham

In 1832 the post of commissioner was replaced by the post of superintendent, who was invested with the same power and authority as the former commissioners, "except in matters requiring an Act of Parliament to be submitted by the Commissioner of the Navy".

Admiral/Captain superintendents

- Note incomplete list included.[22]

- Captain Sir James A. Gordon, July 1832 – 10 January 1837 [23]

- Captain Sir Thomas Bourchier, 20 September 1846 – 5 May 1849 [24]

- Captain Peter Richards, 5 May 1849 – 14 June 1854 [25]

- Captain Christopher Wyvill, 14 June 1854 – 1 April 1861 [26][27]

- Captain Edward G. Fanshawe, 1 April 1861 – 9 November 1863, [28]

- Captain William Houston Stewart, 19 November 1863 to 30 November 1868 [29]

- Captain William Charles Chamberlain, 30 November 1868 – 19 January 1874

- Captain Charles Fellowes, 19 January 1874 – 1876

- Rear-Admiral Thomas Brandreth, 1 February 1879 – 1 December 1881

- Rear-Admiral George W. Watson, 1 December 1881 – April 1886

- Rear-Admiral William Codrington, April 1886 – 1 November 1887

- Rear-Admiral Edward Kelly , 1 November 1887 – December 1890

- Vice-Admiral George D. Morant, 25 January 1892

- Rear-Admiral Hilary G. Andoe, 2 September 1895

- Rear-Admiral Swinton Colthurst Holland, 2 September 1899 – 2 September 1902

- Vice-Admiral Robert William Craigie, 2 September 1902 – 2 September 1905[30]

- Rear-Admiral Alvin C. Corry, 2 September 1905

- Vice-Admiral George A. Giffard, 5 February 1907 – 9 August 1909

- Rear-Admiral Robert N. Ommanney, 9 August 1909 – 9 August 1912

- Rear-Admiral Charles E. Anson, 9 August 1912 – 9 August 1915

- Captain Harry Jones, 16 August 1913 – 15 September 1913

- Vice-Admiral Arthur D. Ricardo, 9 August 1915 – 1 May, 1919

- Rear-Admiral Sir William E. Goodenough, 1 May, 1919 – 26 May, 1920

- Rear-Admiral Lewis Clinton-Baker, 26 May, 1920

- Rear-Admiral Edward B. Kiddle, 28 September 1921 – 1 December 1923

- Rear-Admiral Percy M. R. Royds, 1 December 1923

- Rear-Admiral Charles P. Beaty-Pownall, 7 December 1925 – 7 December 1927

- Rear-Admiral Anselan J. B. Stirling, 7 December 1927

- Vice-Admiral Charles W. Round-Turner, October 1931 – October 1935

- Vice-Admiral Sir Clinton F. S. Danby, 1 October 1935 – 15 October 1942

- Vice-Admiral John G. Crace, 15 October 1942 – July 1946

- Rear-Admiral A.L. Poland, 5 September 1950 – May 1951 [31]

- Rear-Admiral George V.M. Dolphin: October 1954 – October 1958

- Rear-Admiral John Y. Thompson: October 1958 – February 1961

Flag Officer, Medway and Admiral Superintendent

Included: [32]

- Rear-Admiral I.William T. Beloe: February 1961 – December 1963

- Rear-Admiral Ian L.T.Hogg: December 1963 – July 1966

- Vice-Admiral Sir W. John Parker: July 1966 – September 1969 [33]

- Rear-Admiral Frederick C.W. Lawson: September 1969 – November 1971 [34]

Flag Officer, Medway and Port Admiral

- Rear-Admiral Colin C.H. Dunlop: November 1971 – January 1974 [35]

- Rear-Admiral Stephen F. Berthon: January 1974 – July 1976

- Rear-Admiral Christopher M. Bevan: July 1976 – August 1978 [36]

- Rear-Admiral Charles B. Williams: August 1978 – August 1980

- Rear-Admiral George M.K. Brewer: August 1980 – August 1982

- Rear-Admiral William A. Higgins: August 1982–1983 [37]

Of Note: On 5 September 1971 all Flag Officers of the Royal Navy holding positions of Admiral Superintendents at Royal Dockyards were restyled as Port Admirals.[38]

Descriptions

- William Camden (1551–1623) described Chatham dockyard as

- stored for the finest fleet the sun ever beheld, and ready at a minute’s warning, built lately by our most gracious sovereign Elizabeth at great expense for the security of her subjects and the terror of her enemies, with a fort on the shore for its defence.[39]

- Daniel Defoe visiting the yard in 1705, also spoke of its achievements with an almost incredulous enthusiasm:

- So great is the order and application there, that a first-rate vessel of war of 106 guns, ordered to be commissioned by Sir Cloudesley Shovell, was ready in three days. At the time the order was given the vessel was entirely unrigged; yet the masts were raised, sails bent, anchors and cables on board, in that time.[40]

Significant buildings within the Georgian Dockyard

Wood and canvas

- The Mast Ponds. 1697,1702. Fir logs were seasoned by immersing them in salt water while the sap died back.

- Clocktower building 1723. The oldest surviving naval storehouse in any Royal Dockyard. The ground floor was a "present use store" and the upper floor was a mould loft. It was rebuilt in 1802 – the timber cladding was replaced by brick. In the 20th century it was used for offices, and was adapted in 1996-7 to become the University of Kent's Bridge Warden's College.[42][43]

- Sail and Colour Loft 1723. Constructed from timber recycled from warships probably from the Dutch Wars. Lower floors were for storage, and the upper floor is a large open space for sail construction. In 1758 there were 45 sailmakers. They sewed 2 ft (0.61 m) strips of canvas into the sails using 170 – 190 (5 stitches per inch) stitches per yard, remembering that there would be 2 rows of stitching to each seam. Flags denoting nationality and for signals were made here. The flags used by Nelson in his "England expects..." message would have been made here.[44]

- Timber Seasoning Sheds 1774. These were built to a standard design with bays 45 ft (13.7m) by 20 ft (6.1m). These are the first standardised industrial buildings. There were 75 bays erected at Chatham Dockyard, to hold three years worth of timber.[45]

- Wheelwrights' shop c1780. This three bay building was built as a mast house using "reclaimed" timber. The top bay was used by the wheelwrights, who constructed and repaired the wheels on the dockyard carts, and may have made ships' wheels. The middle bay was used by the pumpmakers and the coak and treenail makers. Pumps were simple affairs, made of wood with iron and leather fittings. Coaks were the bearings in pulley blocks, and treenails were the long oak pins, made on a lathe, or moot that were used to pin the planking to the frames. The west bay was used by the capstan makers, capstans were used to raise the anchor.[46]

- Masthouses and Mouldloft 1753–55. Grade I listed since August 1999.[47] These were used to make and store masts. Here there are 7 interlinking masthouses. Above them is the mould loft where the lines of HMS Victory were laid down. The lines of each frame of a ship would be taken from the plan and scribed, full size, into the floor by shipwrights. From this, patterns or moulds would be built using softwoods, and from these the actual frames would be built and shaped. This building houses the "Wooden Walls Exhibition".[48]

- Joiners Shop c. 1790 originally to make treenails, but later used by the yards joiners. The Resolute Desk (the Oval Office desk) was constructed here by Dockyard Joiners from the timbers of HMS Resolute.[49]

- Lower Boat House c1820 built as a storehouse for squared timber, and later to store ship's boats.[41]

- The Clocktower Building

- Sail and Colour Loft

- Timber Seasoning sheds

- Wheelwrights' shop

- Masthouses and Mould Loft

- Joiners' Shop

Lower Boat House and North Mast Pond

Lower Boat House and North Mast Pond

Dry docks and covered slips

- The covered slips 1838–55. It was on slipways that ships were built. The slipways were covered, to prevent ships rotting before they had been launched. The earliest covered slips no longer exist. By 1838 the use of cast and wrought iron in buildings had become feasible. The oldest slip had a wooden roof, three had cast iron roofing and the last used wrought iron. They are of unique importance in the development of wide span structures such as were later used by the railways.

- No 3 Slip 1838. This had a linked timber roof truss structure and was originally covered in tarred paper, which was quickly replaced with a zinc roof. The slip was backfilled around 1900 and a steel mezzanine floor was added. It became a store house for ship's boats.[50]

- No 4, 5 and 6 Slips 1848. These were designed by Captain Thomas Mould, Royal Engineers, and erected by Bakers and Sons of Lambeth. Similar structures were erected at Portsmouth but these are no longer extant. They predate the London train sheds of Paddington and King's Cross which were often cited as the country's first wide span metal structures.[50]

- No 7 Slip is one of the earliest examples of a modern metal trussed roof. It was designed in 1852 by Colonel Godfrey T. Green, Royal Engineers. It was used for shipbuilding until 1966; HMS Ocelot was launched from there on 5 May 1962.[51]

- Dry Dock. The docks are filled by sluice gates set into the caissons, and emptied by a series of underground culverts connected to the pumping station.

- No 2 Dry Dock 1856 was built on the site of "The Old Single Dock" where HMS Victory was constructed. In 1863, this dock constructed HMS Achilles, the first iron battleship to be built in a Royal Dockyard. It now houses HMS Cavalier.[42]

- No 3 Dry Dock 1820, the first to be constructed of stone, was designed by John Rennie. It now houses HMS Ocelot.[42]

- No 4 Dry Dock 1840 now houses HMS Gannet.[42]

- South Dock Pumping Station 1822, designed by John Rennie. It originally housed a beam engine, which was replaced by an electric pump in 1920. The building is still in use.[42]

- No 3 Covered Slip

No 3 Covered Slip (interior)

No 3 Covered Slip (interior) Nos 4-6 Covered Slips

Nos 4-6 Covered Slips- No 6 Covered Slip (interior)

- No 7 Covered Slip

- No 7 Covered Slip (interior)

Slip covers viewed from the river

Slip covers viewed from the river No 2 Dry Dock

No 2 Dry Dock No 3 Dry Dock

No 3 Dry Dock- No 4 Dry Dock

- South Dock pumping station

Offices and residential

- Commissioner's House 1704. This is the oldest surviving naval building in England. It is Grade I listed.[52] It was built for the Resident Commissioner, his family and servants. The previous building was built in 1640 for Phineas Pett. In 1703, Captain George St Lo took up the post and petitioned the Admiralty for a more suitable residence. Internally the principal feature is the main staircase with its painted wooden ceiling attributed to Thomas Highmore (Serjeant Painter), to sketches by Sir James Thornhill.[53]

- Commissioner's Garden dating from 1640. The lower terraces are one of the first Italianate Water Gardens in England. There is a 400-year-old mulberry tree, from where Oliver Cromwell reputedly watched the Roundhead Army take Rochester from the Royalists. There is an 18th-century icehouse and an Edwardian conservatory with its great vine.[54]

- Officers' Terrace 1722-3. Twelve houses built for senior officers in the Dockyard. The ground floor were built as offices, the first floor contained reception rooms with bedrooms above. Each has a 18C walled garden, which again are now very rare. They are now privately owned.[49]

- House Carpenters' Shop c 1740. Built to harmonise with the officers' terrace. House Carpenters worked solely on maintaining the dockyard buildings.[49]

- Stables. For officers' horses.[44]

- Main gatehouse 1722, designed by the master shipwright in the style of Vanbrugh. It bears the arms of George III. Inside the gateway stands the muster bell on a wrought iron mast dating from the late 18th or early 19th century; it is Grade II* listed.[55][56]

- Guard House 1764. Built when Marines were introduced into the Dockyard to improve security. It continued in use till 1984.[44]

- Cashiers' Office 18C. John Dickens, father of Charles Dickens, worked here from 1817 to 1822. It is still used as offices.[49]

- Assistant Queen's Harbourmaster's Office c. 1770, Grade II* listed.[57] This office was supplied to the person who has been appointed to superintend the Dockyard Port. In 1865, the whole of the tidal Medway from Allington Lock to Sheerness was designated as a dockyard port and the Assistant Queen's Harbourmaster was responsible for all moorings and movements. Alongside this office is a set of stone steps leading into the river Medway, with a wrought iron arch and lantern holder. Also Grade II listed.[58] This was called the "Queen Stairs"[59] and was the formal entry into the dockyard, during the "Age of Sail".[54]

- Admiral's Offices 1808. Designed by Edward Holl as offices for the master shipwright. The roofline was low so it would not obstruct the view from the officers' terrace. Later it became Port Admiral's office and was extended. The northern extension became the dockyard's communication centre.[53]

- Thunderbolt Pier, a pier named after HMS Thunderbolt, built 1856, which was used as a floating pier from 1873 until 1948, when she was rammed and sunk.[60]

- Captain of the Dockyard's House 19C. Now used as offices. Also Grade II* listed.[61][62]

Commissioner's House

Commissioner's House- The Commissioner's House (garden view)

- The entrance to the Ice House

The Edwardian conservatory

The Edwardian conservatory- Officers' Terrace

The Officers' Stables

The Officers' Stables- The Main Gate from outside

The Main Gate from inside

The Main Gate from inside The bell mast

The bell mast- The Guardhouse

- The Cashier's Office

Assistant Queen's Harbourmaster's Office

Assistant Queen's Harbourmaster's Office- The Admiral's Office

- The Captain of the Dockyard's House

Anchor Wharf and the Ropery

- Anchor Wharf Store Houses 1778–1805 (at nearly 700 feet long) are the largest storehouses ever built for the navy.[63]

- The southern building, Store House No 3, completed in 1785, is subdivided with timber lattice partitions as a "lay apart store", a store for equipment from vessels under repair. It has been Grade I listed since August 1999.[63]

- The northern building was used as a fitted rigging house, and a general store for equipment to fit out newly built ships. It also has been Grade I listed since August 1999.[64] The Fitted Rigging House is now used as the Library and houses the Steam Steel and Submarines 1832–1984 gallery.[65]

- The Ropery consists of Hemp Houses (1728 extended 1812), Yarn Houses and a double Rope House with attached Hatchelling House. Hatchelling is combing the hemp fibres to straighten them out before spinning. This was the first stage of the ropemaking process. The Ropery is still in use, being operated by Master Ropemakers Ltd.[66]

- The Double Rope House has spinning on the upper floors and ropemaking (a ropewalk) on the ground floor.[67] It is 346 m (1135 ft) long, and when constructed was the longest brickbuilt building in Europe capable of laying a 1,000 ft (300 m) rope. Over 200 men were required before 1836, to make and lay a 20in (circumference) cable. All was done by hand. Steam power in the form of a beam engine was introduced in 1836, and then electricity in the early 1900s.

- The White Yarn House to store the yarn before it was tarred to prevent rot.

- The Tarring House with its "Tar Kettle" and horse drawn winch.

- The Black Yarn House to store the tarred yarn. The tarring process declined as manila replaced hemp, and sisal replaced manila. These fibres were chemically protected at the hatchelling stage and tarring stopped in the 1940s.

- Anchor Wharf Store Houses

- Hemp Houses and Hatchelling House

- Hemp Houses and Double Ropewalk

- Double Ropewalk and Black Yarn House to right

- Laying the Rope

- Looking at the Traveller

- Tops

- The Traveller

Later buildings

- No 1 Smithery 1808. It was designed by Edward Holl, for production of Anchors and Chain. Anchors could weigh 72 cwt (3657 kg), and were forged by hand. "Anchorsmiths" were given an allowance of 8 pints of strong beer a day, because of the difficult working conditions.[45]

- Dockyard Church 1806. Designed by Edward Holl, it has a gallery supported on cast iron columns, one of the first uses of cast iron in the dockyard. Last used in 1981.[44]

- Brunel Saw Mill 1814. Until 1814 timber was cut by pairs of men, one above and one below the log. In 1758, there were 43 pairs of sawyers working in the yard. In 1812, the sawmill was designed by Marc Brunel, father of Isambard Kingdom Brunel. The mill was driven by steam. The mill was linked to the mast ponds by a mechanical timber transport system, and underground canals. Later the basement was converted into a steam laundry.[45]

- Lead and Paint Mill 1818. Designed by Edward Holl to be fireproof. There were a lead furnace, casting area and steam powered double rolling mill, paint mills for grinding pigment, canvas stretching frames, and vats for storing and boiling linseed oil. A warship was painted every 4 months.[56]

- No 1 Machine Shop. This building retains it original structure and roof glazing. It was used to house the machine tools needed to produce HMS Achilles, the first iron battleship built in a Royal Dockyard. This building has now become home to the railway workshop.[42]

- The Galvanising Shop c1890. Galvanising is a process of dipping steel in molten zinc to prevent it from rusting. There were baths of acid and molten zinc, the fumes vented through louvres in the roof.[45]

- Chain Cable Shed c1900, built to protect newly manufactured anchor chain. It is supported by a row of 28 captured French and Spanish guns.[56]

No 1 Smithery

No 1 Smithery Dockyard Church

Dockyard Church- Dockyard Church (interior)

- Brunel Sawmill

- Brunel Sawmill

- Lead and Paint Mill

- No 1 Machine Shop

- Galvanising Shop

Surviving structures within the Victorian Dockyard

- The Victorian Steam Yard was built around three large Basins, constructed between 1865 and 1885 along the line of St Mary's Creek (separating St Mary's Island from the mainland). It was envisaged that Basin No 1 would serve as a "repair basin", No 2 as the "factory basin" and No 3 as the "fitting-out" basin; a newly launched ship could therefore enter via the west lock, have any defects remedied in the first basin, have its engines and heavy machinery installed in the second, and then be finished, and loaded with coal and provisions, in the third before leaving via the east locks.[7]

- Four dry docks (Nos 5–8) were constructed at the same time on the south side of No 1 Basin; all four were in use by 1873. The yard's Steam Factory complex was built at around the same time; most of its buildings were sited around these docks (rather than by Basin No 2 as had originally been planned).[68]

- No 1 Boiler Shop and No 8 Machine Shop were originally built as slip covers at Woolwich Dockyard in the 1840s. When that Dockyard closed in 1869 they were dismantled and rebuilt at Chatham alongside the new dry docks. Only the framework survives of the Machine Shop, but the Boiler Shop was renovated in 2003 to house the Dockyard Outlet shopping centre. A third such structure from Woolwich, similar in design to the boiler shop, stood nearby and served as a fitting shop; it was demolished in 1990.[69]

- Dock Pumping Station 1874: as well as serving to empty dry docks 5–8 when required, its accumulator tower provided hydraulic power for the adjacent cranes, capstans and caissons.[70] Two other pumping stations served a similar purpose (one for dock 9 and one for the two east locks) but they have not survived.[7]

- Combined Ship Trade Office 1880: now the "Ship & Trades" public house.[71]

- The 100 ft bell mast was erected in 1903 alongside the Dockyard's Pembroke Gate, where it was used to signal the start of each working day. (A similar but older mast fulfilled the same function alongside the main gate in the Georgian part of the Yard.) The 1903 mast had originally served as foremast to HMS Undaunted. In 1992 it had been dismantled, but was re-erected, a short distance from its original location, in 2001. Apart from the two Chatham examples, only one other is believed to have survived: in Devonport's Morice Ordnance Yard.[72]

- A fifth dry dock (No 9) was added in 1895 on the north side of No 1 Basin, opposite the other four, to accommodate the new, larger battleships which were then under construction. It was completed in 1903.

Expanse of water in No 2 Basin

Expanse of water in No 2 Basin View down the length of the former No 7 Dock towards No 1 Basin (now Chatham Marina)

View down the length of the former No 7 Dock towards No 1 Basin (now Chatham Marina)- Remains of No 8 Machine Shop with No 1 Boiler Shop behind it

Dock pumping station (its 80 ft chimney, formerly on the plinth to the right, has been removed)

Dock pumping station (its 80 ft chimney, formerly on the plinth to the right, has been removed) Bell Mast on Leviathan Way

Bell Mast on Leviathan Way Combined Ship Trade Office

Combined Ship Trade Office.jpg) Former No 1 Boiler Shop (with clock)

Former No 1 Boiler Shop (with clock)

The Gun Wharf

An Ordnance Yard was established in the 17th century immediately upriver of the Dockyard (on the site of the original Tudor yard, vacated in 1622). The yard would have received, stored and issued cannons and gun-carriages (along with projectiles, accoutrements and also all manner of small arms) for ships based in the Medway, as well as for local artillery emplacements and for army use. (Gunpowder, on the other hand, was received, stored and issued across the river at Upnor Castle.)

A plan of 1704 shows (from north to south) a long Storehouse parallel to the river, the Storekeeper's house (the Storekeeper was the senior officer of the Yard) and a pair of Carriage Stores. In 1717 the original Storehouse was replaced with the Grand Store (a much larger three-storey building, contemporary with and of a similar style to, the Main Gatehouse in the Dockyard). Not long afterwards a large new single-storey Carriage Store, with a long frontage parallel to the river, was constructed, adjoining the Storekeeper's House to the south.

After the demise of the Board of Ordnance (1855), Ordnance Yards passed under the control of the War Office, and were eventually (in 1891) apportioned to either the Army or the Navy. Chatham's yard was split in two, the area south of the Storekeeper's House becoming an Army Ordnance Store, and the rest a Navy Ordnance Store. It remained thus until 1958 when the yards were closed (the Army depot having served latterly as an atomic weapons research laboratory).[73] Most of the 18th-century buildings were demolished, with the exception of the Storekeeper's House of 1719, which survives as the Command House public house.[74] A few later buildings have survived: a long brick shed of 1805, south-west of the Command House, which once housed carpenters, wheelwrights and other workers as well as stores of various kinds,[75] the adjacent building (machine shop, late-19th century) which now serves as a public library, and the building known as the White House (built as the Clerk of the Cheque's residence in 1816).[7]

Defence of the dockyard

Upnor Castle

Dockyards have always required shore defences. Among the earliest for Chatham was Upnor Castle, built in 1567, on the opposite side of the River Medway. It was somewhat unfortunate that, on the one occasion when it was required for action—the Raid on the Medway, 1667—the Dutch fleet were able to sail right past it to attack the English fleet and carry off the pride of the fleet, HMS Royal Charles, back to the Netherlands.[76]

Chain defence

During the wars with Spain it was usual for ships to anchor at Chatham in reserve; consequently John Hawkins threw a massive chain across the River Medway for extra defence in 1585. Hawkins' chain was later replaced with a boom of masts, iron, cordage, and the hulls of two old ships, besides a couple of ruined pinnacles.[77]

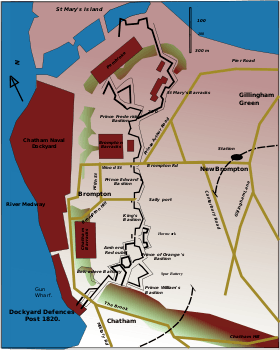

The Lines

With the failure of Upnor Castle, it was seen necessary to increase the defences. In the event, those defences were built in distinct phases, as the government saw the increasing threat of invasion:[78]

- 1669 Fort Gillingham and Cockham Wood Fort built.

- 1756 Chatham Lines built, to designs by Captain John Desmaretz (who also designed the Portsmouth fortifications).[78] This fortification, and its subsequent upgrading, were to concentrate on an overland attack and so were built to face south. They included redoubts at Amherst and Townsend. The Lines enclosed the entire dockyard on its eastern side.

- 1778–1783 Further improvements were carried out, to the designs of Captain Hugh Debbeig at the bequest of General Amherst. In 1782, an Act of Parliament increased the land needed for the Field of Fire.[78]

- 1805–1812 Amherst redoubt, now Fort Amherst; new forts, named Pitt and Clarence. The Lines were also extended to the east of Saint Mary’s Creek (on St Mary's Island).[78]

- 1860s Grain Fort, and other smaller batteries in that area.

- 1870–1892 A number of forts built at a greater distance from the dockyard: Forts Bridgewood, Luton, Borstal, Horsted and Darland. These became known as the "Great Lines". Forts Darnet and Hoo built on islands in the River Medway.

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

Associated barracks

The Dockyard led to large numbers of military personnel being garrisoned in Chatham and the surrounding area. A good many were engaged in manning the defences, but some had other duties; others were accommodated there for convenience prior to embarking on ships for duties overseas, or following their disembarkation. Initially, soldiers were housed under canvas or else billetted in houses and inns, but from the 18th century barracks began to be constructed. The oldest surviving barracks in the Chatham area is in Upnor; dating from 1718, it housed the detachment of 64 men responsible for guarding the gunpowder store in Upnor Castle.

Infantry Barracks (Kitchener Barracks)

Chatham Infantry Barracks was opened in 1757 to house troops manning the fortifications which had recently been built to defend the Dockyard. Within the space of 20 years it had taken on the additional role of national recruitment centre for the British Army, providing basic training for all new recruits. This role ceased in 1803, but the barracks went on to serve as a home depot for numerous regiments stationed around the globe. Accommodating some 1,800 men, Chatham was one of the first large-scale Army barracks in England, and remained in military use until 2014.[79] One barrack block remains from 1757; the rest was largely demolished and rebuilt to a more modern design in the 1930s–50s. In 1928 the barracks was taken over by the Royal Engineers and renamed Kitchener Barracks. In 2014 the site was sold to a property developer, with permission given the following year for the building of 295 homes. The main 1930s barracks building will be retained, along with the remaining earlier structures.[80]

Marine Barracks

The Royal Marine Barracks, Chatham were established in 1779, on a site nestled between the Gun Wharf to the west, the Dockyard to the north, and Infantry Barracks to the east. The site was expanded and rebuilt in the 1860s; in 1905 the Royal Marines took over Melville Barracks, which stood between Dock Road and Brompton Hill (it had formerly served as Chatham's Royal Naval Hospital). The Marines were withdrawn from Chatham in 1950, and the buildings were later demolished. Medway Council offices and car park now stand on the site.[81]

Artillery/Engineer Barracks (Brompton Barracks)

_-_geograph.org.uk_-_517097.jpg)

A barracks was built in Brompton in 1804-6 for the Royal Artillery gunners serving on the defensive Lines (previously they had been accommodated in the Infantry Barracks). There was space for some 500 horses and 1,000 men. In 1812 the Royal Engineers Establishment was founded within the barracks to provide instruction in military engineering. The Establishment grew, and by 1856 the Artillery had moved out; Brompton Barracks remains in service as headquarters of the Royal Engineers.[82]

St Mary's Barracks

St Mary's Casemated Barracks were built during the Peninsular War and initially held French prisoners of war. After the war's end, they went on to serve as a gunpowder store for a time, and were used by the Royal Engineers (based nearby in Brompton Barracks). From 1844 St Mary's was used as an 'Invalid Barracks', accommodating soldiers having to return from service in different parts of the British Empire because of illness, injury or age.[83] Built within the defensive earthworks to the north of Chatham, St Mary's Barracks was demolished in the 1960s and the land used for housing.[84]

Naval Barracks (HMS Pembroke)

The Naval Barracks (later HMS Pembroke) opened in 1902; prior to this, most Naval (as opposed to Dockyard) personnel were accommodated on board their ships or on hulks moored nearby. Built on the site of what had been a convict prison, the barracks complex could accommodate 4,742 officers and seamen in a series of large blocks built along the length of a terrace. Below the terrace lay the parade ground and its adjacent drill hall and other amenities. A further 3,000 troops could be accommodated in times of "total emergency" (900 were sleeping in the Drill Hall when it suffered a direct hit from two bombs in September 1917, which killed over 130 men). The barracks were set to close in 1961 when the majority of naval personnel were withdrawn from Chatham;[85] however, it went on to serve instead as the RN Supply and Secretariat School in succession to HMS Ceres, before finally being closed along with the Dockyard in 1984. The majority of its buildings are still standing, several of them occupied by the Universities at Medway.[86]

Former Commodore's residence

Former Commodore's residence Former barracks church

Former barracks church Former barrack blocks

Former barrack blocks Former officers' quarters

Former officers' quarters Former drill hall with offices behind

Former drill hall with offices behind Gymnasium

Gymnasium Former gunnery school

Former gunnery school

Closure and regeneration

The dockyard closed in 1984. It covered 400 acres (1.6 km²). After closure this was divided into three sections. The easternmost basin (Basin No 3) was handed over to the Medway Ports authority and is now a commercial port. It includes Papersafe UK[87] and Nordic Recycling Ltd.[88] 80 acres (324,000 m²), comprising the 18th century core of the site, was transferred to a charity called the Chatham Historic Dockyard Trust and is now open as a visitor attraction.[89]

St Mary's Island, a 150-acre (0.61 km2) site once a part of the Dockyard, has been transformed into a residential community for some 1,500 homes. It has several themed areas with traditional maritime buildings, a fishing (though in looks only) village with its multi-coloured houses and a modern energy-efficient concept. Many homes have views of the River Medway. A primary school (St. Mary's CofE) and a medical centre provide facilities for the residents and there are attractive walks around the Island.[90]

Peel Ports, who run a 26-acre (0.11 km2) portion of the commercial port on Basin No 3, are about to transform a former brownfield site into mixed use development incorporating offices, an education facility, an "EventCity", a hotel, apartments, town houses and a food store (Asda), as well as landscaped public areas. The development will be called "Chatham Waters", even though it is on East Wharf of the Chatham Docks.[91] A second planning application for the development has been approved by Medway Council. The original planning application included plans for a pub/restaurant and a café, but these have been removed.[92]

Filming

Chatham Dockyard has become a popular location for filming, due to its varied and interesting areas such as the cobbled streets, church and over 100 buildings dating from the Georgian and Victorian periods. Productions that have chosen to film at Chatham Dockyard include: Les Misérables,[93] Call the Midwife,[94] Mr Selfridge,[95] Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows,[96] Oliver Twist[97] and The World Is Not Enough.[98]

See also

References

- ↑ "20th-century naval dockyards characterisation report, part 1: introduction". Historic England. Naval Dockyards Society. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ↑ "Research guide: Royal Dockyard names and locations". National Archives. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- 1 2 Guidebook, p. 28

- ↑ "Visits to Rochester and Chatham" (PDF). Kent Archaeology. p. 55.

- 1 2 Guidebook, p. 29

- ↑ Hughes, David T. (2002). Sheerness Naval Dockyard and Garrison. Stroud, Gloucs.: The History Press.

- 1 2 3 4 Coad, Jonathan (2013). Support the Fleet: Architecture and engineering of the Royal Navy's bases, 1700–1914. Swindon: English Heritage.

- ↑ Eastland & Ballantyne, p. 13

- ↑ "Chatham Dockyard". Battleships cruisers. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ↑ "HMS Unicorn: Summary from the Official HMS Unicorn website". Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ↑ "Chatham Dockyard: Lasting impact three decades on". BBC. 31 March 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ↑ "World heritage bid for dockyard". BBC. 6 June 2007. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ Beaston , p. 351

- ↑ Perrin, p. 146

- ↑ "Peter Pett (1610–1672)". History of Parliament. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- ↑ Sephton, p. 151

- ↑ Beaston 1788, p. 85

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Beaston 1788, p. 351

- ↑ MacDonald, p.230

- ↑ "Charles Hope". More than Nelson. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ Marshall, p. 48

- ↑ Harley, Simon; Lovell, Tony. "Chatham Royal Dockyard – The Dreadnought Project". dreadnoughtproject.org. Lovell and Harley, 17 July 2017. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ↑ Government, H.M. (20 March 1834). "Dockyards: Officers". The Navy List. London: H.M. Stationary Office. p. 136.

- ↑ Government, H.M. (20 June 1848). "Dockyards: Officers". The Navy List. London: H.M. Stationary Office. p. 163.

- ↑ Government, H.M. (20 December 1853). "Dockyards: Officers". The Navy List. London: H.M. Stationary Office. p. 189.

- ↑ Government, H.M. (20 September 1854). "Dockyards: Officers of". The Navy List. John Murray. p. 191.

- ↑ Laughton, John Knox. "Wyvill Christopher (1792–1863)". Dictionary of National Biography, 1885–1900. Wikisource, 24 April 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ↑ Government, H.M. (20 June 1863). "Dockyards: Officers of". The Navy List. John Murray. p. 232.

- ↑ Government, H.M. (20 December 1867). "Dockyards: Officers of". The Navy List. John Murray. p. 259.

- ↑ "Naval & Military intelligence". The Times (36862). London. 2 September 1902. p. 4.

- ↑ Government, H.M. (May 1951). "Principle Officers in the Dockyards". The Navy List. H.M. Stationary Office. p. 362.

- ↑ Mackie, Colin. "Royal Navy Senior Appointments from 1865". gulabin.com. Colin Mackie, pp.108–109. February 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ↑ Vat, Dan van der (12 June 2005). "Obituary: Vice Adm Sir John Parker". the Guardian. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ↑ Obituary (30 March 2010). "Rear-Admiral Derick Lawson". Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ↑ Obituary (29 March 2009). "Rear-Admiral Colin Dunlop". Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ↑ "Person Page". www.thepeerage.com. The Peerage, 8 February 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ↑ Obituary (6 February 2007). "Rear-Admiral Bill Higgins". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ↑ "1971 – Admiral Superintendents become Port Admirals – Portsmouth Royal Dockyard Historical Trust". portsmouthdockyard.org.uk. Portsmouth Historical Dockyard Trust. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ↑ Brayley and Britton, p. 667

- ↑ "Kanye video to become a museum exhibit". The Guardian. 20 July 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 Guidebook, p. 27

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Guidebook, p. 14

- ↑ "Bridge Wardens' College Teaching and Meeting Rooms". www.kent.ac.uk. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Guidebook, p. 23

- 1 2 3 4 Guidebook, p. 26

- ↑ Guidebook, p. 9

- ↑ "Former Mast House and Mould Loft, Medway". www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- ↑ Guidebook, p. 8

- 1 2 3 4 Guidebook, p. 25

- 1 2 Guidebook, p. 10

- ↑ Guidebook, p. 12

- ↑ "Former Commissioners House and Attached Staff Accommodation, Medway". www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- 1 2 Guidebook, p. 15

- 1 2 Guidebook, p. 16

- ↑ Historic England. "Bell Mast (1378626)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 Guidebook, p. 22

- ↑ "Former Assistant Queens Harbourmasters Office, Medway". www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ↑ "Queens Stairs with Overthrow Arch, Medway". www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ↑ "Steps from Quay, Chatham Historic Dockyard, Kent". www.geograph.org.uk. 21 August 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ↑ "Thunderbolt Pier and Kingswear Castle, Chatham". UK BeachesGuide. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ "Former Captain of the Dockyards House and Attached Front Area Railings, Medway". www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ↑ Guidebook, p. 24

- 1 2 "Former Storehouse Number 3 and Former Chain Cable Store, Medway". www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ↑ "Former Storehouse Number 2 and Former Rigging Store, Medway". www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ↑ Guidebook, p. 17

- ↑ "Master Ropemakers Chatham". www.master-ropemakers.co.uk. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ↑ Guidebook, p. 18

- ↑ Guidebook, p. 30

- ↑ "Engineering timelines".

- ↑ Historic England. "Dock Pumping Station (1246993)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- ↑ Historic England. "Combined Ship Trade Office (1267779)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- ↑ "Bell Mast".

- ↑ "English Heritage report:AWRE Foulness" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2015.

- ↑ "Listed building description (Command House)".

- ↑ "Listed building description (Ordnance Store)".

- ↑ Saunders, p. 14

- ↑ "Records of the hospital of Sir John Hawkins Kt in Chatham (1500) 1594–1987". National Archives. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Brompton Lines Conservation Area Appraisal (Adopted Version)" (PDF). www.medway.gov.uk. May 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ↑ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1410725)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ↑ "Kitchener Barracks to be converted for housing". Kent on line. 30 April 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ "Chatham Royal Naval Division Barracks". Roll of Honour. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ "Brompton Barracks". Brompton History. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ "Illustrated London News, March 8 1856". Kent History Forum. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ↑ "Fort Amherst Guidebook". Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ Copy of government briefing paper

- ↑ Coad, Jonathan (2013). Support for the Fleet. Swindon: English Heritage.

- ↑ Papersafe UK, Berth 6, Basin 3, Chatham | STORAGE. Yell. Retrieved on 17 July 2013.

- ↑ "Nordic Recycling" (PDF).

- ↑ "Economic impact of the Historic Dockyard Chatham". Chatham Historic Dockyard. Archived from the original on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ "St Mary's Island". Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ "Chatham Waters". www.peel.co.uk. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ↑ ""New era" for Gillingham as Chatham Docks approved". insidermedia.com. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ↑ Kent Film Office. "Kent Film Office Les Miserables Film Focus".

- ↑ Kent Film Office. "Kent Film Office Call The Midwife Film Focus".

- ↑ Kent Film Office. "Kent Film Office Mr Selfridge Film Focus".

- ↑ Kent Film Office. "Kent Film Office Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows Film Focus".

- ↑ Kent Film Office. "Kent Film Office Oliver Twist Film Focus".

- ↑ Kent Film Office. "Kent Film Office The World is Not EnoughFilm Focus".

Sources

- The Annual Biography and Obituary for the Year. Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown. 1835.

- Guidebook. Chatham Historic Dockyard Trust. 2010.

- Beaston, Robert (1788). A Political Index to the Histories of Great Britain and Ireland. I. G.G.J. and J. Robinson.

- Beaston, Robert (1806). A Political Index to the Histories of Great Britain and Ireland. I. Longman, Hurst, Rees and Orme.

- Brayley, Edward Wedlake; Britton, John (1808). The Beauties of England and Wales, Or, Delineations, Topographical, Historical and Descriptive of each County. Vernor, Mood and Sharpe.

- Eastland, Jonathan; Ballantyne, Iain (2011). HMS Victory – First Rate 1765. Barnsley: Vernor, Mood and Sharpe. ISBN 978-1-84832-094-9.

- MacDonald, Janet (2010). The British Navy's Victualling Board, 1793-1815: Management Competence and Incompetence. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1843835530.

- Marshall, John (1824). Royal Naval Biography; Or, Memoirs of the Services of All the Flag-officers. Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green.

- Perrin, William Gordon (1918). The autobiography of Phineas Pett. Naval Records Society.

- Saunders, A. D. (1985). Upnor Castle: Kent. English Heritage. ISBN 978-1-85074-039-1.

- Sephton, James (2011). Sovereign of the Seas: The Seventeenth Century Warship. Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1445601687.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chatham Dockyard. |

- Meridian Tonight at the Dockyard Did you know that the iconic White House desk that has sat in the Oval Office since 1880 was built at Chatham Dockyard?

- The Chatham forts

- The Historic Dockyard Trust

- Chatham Dockyard Historical Society website

- Chatham's World Heritage Site application

- A Geometrical Plan, & North West Elevation of His Majesty’s Dock-Yard, at Chatham, with ye Village of Brompton Adjacent, dated 1755 (Pierre-Charles Canot after Thomas Milton and John Cleveley the Elder)