United States abortion-rights movement

Albert Wynn and Gloria Feldt on the steps of the U.S. Supreme Court to rally for legal abortion on the anniversary of Roe v. Wade |

The United States abortion-rights movement (also known as the United States pro-choice movement) is a sociopolitical movement in the United States supporting the view that a woman should have the legal right to an elective abortion, meaning the right to terminate her pregnancy, and is part of a broader global abortion-rights movement. The pro-choice movement consists of a variety of organizations, with no single centralized decision-making body.[1]

A key point in abortion rights in the United States was the U.S. Supreme Court's 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade, which struck down most state laws restricting abortion,[2][3] thereby decriminalizing and legalizing elective abortion in a number of states.

On the other side of the abortion debate in the United States is the movement to extend rights to the pre-born at the expense of restricting the rights of pregnant women, the pro-life movement. Within this group many argue that human life begins at conception.

Overview

Abortion-rights advocates argue that whether or not a pregnant woman continues with a pregnancy should be her personal choice, as it involves her body, personal health, and future. They also argue that the availability of legal abortions reduces the exposure of women to the risks associated with illegal abortions. More broadly, abortion-rights advocates frame their arguments in terms of individual liberty, reproductive freedom, and reproductive rights. The first of these terms was widely used to describe many of the political movements of the 19th and 20th centuries (such as in the abolition of slavery in Europe and the United States, and in the spread of popular democracy) whereas the latter terms derive from changing perspectives on sexual freedom and bodily integrity.

Abortion-rights individuals rarely consider themselves "pro-abortion", because they consider termination of a pregnancy as a bodily autonomy issue, and find forced abortion to be as legally and morally indefensible as the outlawing of abortion. Indeed, some who support abortion rights consider themselves opposed to some or all abortions on a moral basis, but believe that abortions would happen in any case and that legal abortion under medically controlled conditions is preferable to illegal back-alley abortion without proper medical supervision. Such people believe the death rate of women due to such procedures in areas where abortions are only available outside of the medical establishment is unacceptable.

Some who argue from a philosophical viewpoint believe that an embryo has no rights as it is only a potential and not an actual person and that it should not have rights that override those of the pregnant woman at least until it is viable.[4]

Many abortion-rights campaigners also note that some anti-abortion activists also oppose sex education and the ready availability of contraception, two policies which in practice increase the demand for abortion.[5] Proponents of this argument point to cases of areas with limited sex education and contraceptive access that have high abortion rates, either legal or illegal. Some women also travel to another jurisdiction or country where they may obtain an abortion. For example, a large number of Irish women would visit the United Kingdom for abortions, as would Belgian women who travelled to France before Belgium legalized abortion. Similarly, women would travel to the Netherlands when it became legal to have abortions there in the 1970s.

Some people who support abortion rights see abortion as a last resort and focus on a number of situations where they feel abortion is a necessary option. Among these situations are those where the woman was raped, her health or life (or that of the fetus) is at risk, contraception was used but failed, the fetus has acute congenital disorder and defects, incest, financial constraints, overpopulation, or she feels unable to raise a child. Some abortion-rights moderates, who would otherwise be willing to accept certain restrictions on abortion, feel that political pragmatism compels them to oppose any such restrictions, as they could be used to form a slippery slope against all abortions.[6] On the other hand, even some pro-choice advocates feel uncomfortable with the use of abortion for sex-selection, as is practised in some countries, such as India.

History

Prior to 1973, abortion rights in the United States were not seen as a constitutional issue. Abortion was seen as a purely state matter, all of which had some type of restrictions. The first legal restrictions on abortion appeared in the 1820s, forbidding abortion after the fourth month of pregnancy. By 1900, legislators at the urgings of the American Medical Association (AMA) had enacted laws banning abortion in most U.S. states.[7] The AMA played a vital role in stigmatizing abortions by using their status and power to create a moral stance against abortion. The AMA viewed abortion providers as unwanted healthcare competitors.[8] Due to the high maternal morbidity and mortality rates caused by back alley abortions, physicians, nurses, and social workers pushed for legalization of abortion from a pro-public health perspective. [9] Support for abortion rights went beyond feminists and medical professions. The broad support for legalizing abortion in the 1960s also derived from certain religious leaders. For example, there were 1,400 clergy operating on the East Coast for the Clergy Consultation Service on Abortion—an underground network that connected women seeking abortions to doctors—during the 1960s. [10] As the historian Christine Stansell explained, many religious leaders came to approach the abortion rights argument from a position of individual conscience instead of from dogma by witnessing the "strains unwanted pregnancies put on members of their congregations".[11]

In its landmark 1973 case, Roe v. Wade where a woman challenged the Texas laws criminalizing abortion, the U.S. Supreme Court reached two important conclusions:

- That state abortion laws are subject to the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution; and

- That the procurement of an abortion was a constitutional right during the first and second trimesters of a pregnancy based on the constitutional right to privacy, but that the state's interest in protecting "potential life" prevailed in the third trimester unless the woman's health was at risk. In subsequent rulings, the Court rejected the trimester framework altogether in favor of a cutoff at the point of fetal viability (cf. Planned Parenthood v. Casey).

Abortion-rights groups are active in all American states and at the federal level, campaigning for legal abortion and against the reimposition of anti-abortion laws, with varying degrees of success. Only a few states allow abortion without limitation or regulation, but most do allow various limited forms of abortion.

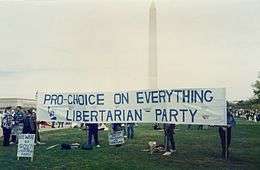

In the United States, the Democratic Party's platform endorses the abortion-rights position, stating that abortion should be "safe, legal, and rare".[12] Not all Democrats agree with the platform, however, and there is a small pro-life faction within the party, expressed in such groups as Democrats for Life of America.[13] Similarly, there is a small abortion-rights faction within the Republican Party. The Libertarian Party holds "that government should be kept out of the matter".[14]

Organizations and Individuals

The pro-choice movement includes a variety of organizations, with no single centralized decision-making body.[1] Many more individuals who are not members of these organizations also support their views and arguments. Many people support the objectives of the movement because of the extreme arguments, objectives and tactics of sections of the anti-abortion movement, such as refusal to accept that in some circumstances (such as rape or incest) an abortion may be justifiable.

Planned Parenthood, NARAL Pro-Choice America, the National Abortion Federation, the National Organization for Women, and the American Civil Liberties Union are the leading abortion-rights advocacy and lobbying groups in the United States. Most major feminist organizations also support abortion-rights positions, as do the American Medical Association, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and pro-choice physicians such as Eugene Gu[15] and Warren Hern[16] who have fought political intimidation from pro-life Congresswoman Marsha Blackburn.[17][18] There are also faith-based groups that advocate for abortion rights. Notably, the Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice and Catholics for Choice.

Terminology controversy

The terms "pro-choice" and "pro-life" are examples of political framing. They are terms which purposely try to define their philosophies in the best possible light, while attempting to define their opposition in the worst possible light: "Pro-choice" implies the alternative viewpoint is "pro-coercion" or "anti-choice", while "pro-life" implies the alternative viewpoint is "pro-death" or "anti-life".[19] Similarly each side's use of the term "rights" ("reproductive rights", "right to life of every unborn child") implies a validity in their stance, given that the presumption in language is that rights are inherently a good thing and so implies an invalidity in the viewpoint of their opponents. (In liberal democracies, a right is seen as something the state and civil society must defend, whether human rights, victims' rights, children's rights, etc. Many states use the word rights in fundamental laws and constitutions to define basic civil principles; both the United Kingdom and the United States possess a Bill of Rights.) Other examples of political framing frequently employed in this context are: "unborn baby", "unborn child", and "pre-born child".[20][21]

The term "pro-life" for those who are opposed to legal abortion is further objected to by activists who support the legalization of abortion because women's lives are lost due to unsafe abortions when abortion is illegal. Some who support abortion consider the term ironic since they say "pro-life" activists oppose the use of abortion procedures even when they are deemed medically necessary to save the life of the pregnant woman, or to resolve a situation that endangers both the life of the woman and the fetus to such an extent that both will die if an abortion is not performed. Members of the abortion-rights movement counter the "pro-life" terminology with the argument that being pro-choice is pro-life: pro-women's lives.

The Associated Press and Reuters encourage journalists to use the terms "abortion rights" and "anti-abortion", which they see as neutral.[22]

See also

References

- 1 2 Schultz, Jeffrey D.; Van Assendelft, Laura A. (1999). Encyclopedia of women in American politics. The American political landscape (1 ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 195. ISBN 1-57356-131-2.

- ↑ Staggenborg, Suzanne (1994). The Pro-Choice Movement: Organization and Activism in the Abortion Conflict. Oxford University Press US. p. 188. ISBN 0-19-508925-1.

- ↑ Greenhouse, Linda (2010). Before Roe v. Wade: Voices that Shaped the Abortion Debate Before the Supreme Court's Ruling. Kaplan Publishing. ISBN 1-60714-671-1. Archived from the original on 2013-01-14. Retrieved 2014-05-05.

- ↑ Johnstone, Megan-Jane (2004). Bioethics: a nursing perspective. Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-7295-3726-1.

- ↑ Cosgrove, Terry (October 24, 2007). "So-Called Pro-Lifers Should Stop Promoting Abortion". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2010-12-27.

- ↑ Zandt, Deanna (2005-11-03). "Husband notification laws and Alito". AlterNet. Retrieved 2006-07-07.

- ↑ Lewis, Jone Johnson. "Abortion History: A History of Abortion in the United States". Women's History section of About.com. About.com. Retrieved 2006-07-07.

- ↑ History Staff. "Roe v. Wade". A+E Networks. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ↑ "Abortion in American History". Atlantic Magazine. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ↑ Steenland, Sally. "The surprising history of abortion in the United States\accessdate=21 April 2017". CNN.

- ↑ Christine Stansell, The Feminist Promise: 1792 to the Present (New York: Modern Library, 2010), 317.

- ↑ "The 2004 Democratic National Platform for America" (PDF). United States Democratic Party. 2004-07-24. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 8, 2007. Retrieved 2007-02-12.

- ↑ Fineman, Howard; Evan Thomas (2006-03-20). "The GOP's Abortion Anxiety". Newsweek Politics. MSNBC. Archived from the original on June 15, 2006. Retrieved 2006-07-07.

- ↑ Plank 1.4 Abortion, at Libertarian Party website.

- ↑ http://www.sciencefriday.com/person/eugene-gu/

- ↑ http://healthland.time.com/2011/01/21/philly-abortion-horrors-what-matters-is-how-and-not-when-an-abortion-is-done-says-expert/

- ↑ http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/eugene-gu-research-congress_us_581a3d79e4b01a82df6460de

- ↑ http://www.dailykos.com/story/2016/11/18/1601020/-Abortion-Doctor-Writes-Powerful-Response-to-Anti-Abortion-Witch-Hunt-by-Congress

- ↑ "Example of 'anti-life' terminology" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved December 9, 2011.

- ↑ Chamberlain, Pam; Hardisty, Jean. "The Importance of the Political 'Framing' of Abortion". Political Research Associates. Retrieved 2011-06-23.

- ↑ "The Roberts Court Takes on Abortion". The New York Times. November 5, 2006. Retrieved January 18, 2008.

- ↑ Goldstein, Norm, ed. The Associated Press Stylebook. Philadelphia: Basic Books, 2007.

Further reading

Books

- Ninia Baehr, Abortion without Apology: A Radical History for the 1990s South End Press, 1990.

- Ruth Colker, Abortion & Dialogue: Pro-Choice, Pro-Life, and American Law Indiana University Press, 1992.

- Donald T. Critchlow, The Politics of Abortion and Birth Control in Historical Perspective University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996.

- Myra Marx Ferree et al., Shaping Abortion Discourse: Democracy and the Public Sphere in Germany and the United States Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Marlene Gerber Fried, From Abortion to Reproductive Freedom: Transforming a Movement South End Press, 1990.

- Beverly Wildung Harrison, Our Right to Choose: Toward a New Ethic of Abortion Beacon Press, 1983.

- Suzanne Staggenborg, The Pro-Choice Movement: Organization and Activism in the Abortion Conflict, Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Raymond Tatalovich, The Politics of Abortion in the United States and Canada: A Comparative Study M.E. Sharpe, 1997.

- Katie Watson, Scarlet A: The Ethics, Law, and Policies of Ordinary Abortion Oxford University Press, 2018.

Articles and journals

- Mary S. Alexander, "Defining the Abortion Debate" in ETC.: A Review of General Semantics, Vol. 50, 1993.

- David R. Carlin Jr., "Going, Going, Gone: The Diminution of the Self" in Commonweal Vol.120. 1993.

- Vijayan K. Pillai, Guang-Zhen Wang, "Women's Reproductive Rights, Modernization, and Family Planning Programs in Developing Countries: A Causal Model" in International Journal of Comparative Sociology, Vol. 40, 1999.

- Suzanne Staggenborg, "Organizational and Environmental Influences on the Development of the Pro-Choice Movement" in Social Forces, Vol. 68, 1989.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pro-choice movement. |

| Look up pro-choice in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |