Yugoslav Wars

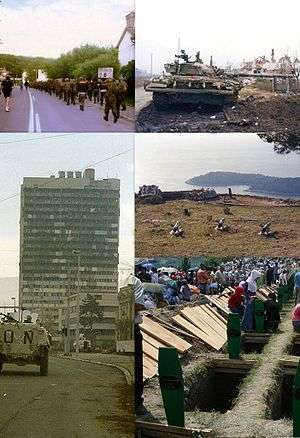

The Yugoslav Wars were a series of ethnic conflicts, wars of independence and insurgencies fought from 1991 in the former Yugoslavia[Note 1] which led to the breakup of the Yugoslav state, with its constituent republics declaring independence despite tensions between ethnic minorities in the new countries (chiefly Serbs, Croats and Muslims) being unresolved. The wars are generally considered to be a series of separate, but related, military conflicts which occurred in most of the former Yugoslav republics.[5][6][7]

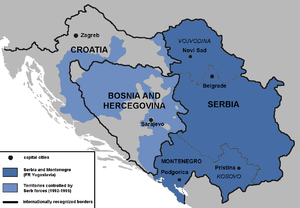

Most wars ended through peace accords, involving full international recognition of new states, but with a massive human cost and economic damage to the region. Initially the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) sought to preserve the unity of the whole of Yugoslavia by crushing the secessionist governments but it increasingly came under the influence of the Serbian government of Slobodan Milošević that evoked Serbian nationalist rhetoric and was willing to use the Yugoslav cause to preserve the unity of Serbs in one state. As a result, the JNA began to lose Slovenes, Croats, Kosovar Albanians, Bosniaks, and ethnic Macedonians, and effectively became a Serb army.[8] According to the 1994 United Nations report, the Serb side did not aim to restore Yugoslavia, but to create a "Greater Serbia" from parts of Croatia and Bosnia.[9] Other irredentist movements have also been brought into connection with the wars, such as "Greater Albania"[10][11][12][13][14] and "Greater Croatia".[15][16][17][18][19]

Often described as Europe's deadliest conflicts since World War II, the wars were marked by many war crimes, including ethnic cleansing, crimes against humanity and rape. The Bosnian genocide was the first European crime since World War II to be formally judged as genocidal in character and many key individual participants were subsequently charged with war crimes.[20] The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) was established by the UN to prosecute these crimes.[21]

According to the International Center for Transitional Justice, the Yugoslav Wars resulted in the death of 140,000 people.[1] The Humanitarian Law Center estimates that in the conflicts in the former Yugoslav republics at least 130,000 people were killed.[2]

Naming

The war(s) have alternatively been called:

- "Wars in the Balkans" (although the wars only affected the west side of the Balkans as well as areas outside it (within Central Europe)

- "Wars/conflicts in the former Yugoslavia".[1][22]

- "Wars of Yugoslav Secession/Succession".

- "Third Balkan War": a term suggested by British journalist Misha Glenny in the title of his book, alluding to the two previous Balkan Wars fought from 1912–13.[23] In fact, this term has been applied by some contemporary historians to World War I, because they see it as a direct sequel to the 1912–13 Balkan wars.[24]

- "Yugoslavia Civil War"/"Yugoslav Civil War"/"Yugoslavian Civil War"/"Civil War in Yugoslavia".

Background

Clear ethnic conflict between the Yugoslav peoples only became prominent in the 20th century, beginning with tensions over the constitution of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes in the early 1920s and escalating into violence between Serbs and Croats in the late 1920s after the assassination of Croatian politician Stjepan Radić. During World War II the Croatian Ustaše committed a number of atrocities against the Serbs and Serbian Chetniks against the Croats and Bosniaks. The Yugoslav Partisan movement was able to appeal to all groups, including Serbs, Croats, and Bosniaks.[5][26] In Serbia and Serb-dominated territories, violent confrontations occurred, particularly between nationalists and non-nationalists who criticized the Serbian government and the Serb political entities in Bosnia and Croatia.[27] Serbs who publicly opposed the nationalist political climate during the Yugoslav wars were reportedly harassed, threatened, or killed.[27]

The nation of Yugoslavia was created in the aftermath of World War I, and it was mostly composed of South Slavic Christians, but the nation also had a substantial Muslim minority. This nation lasted from 1918 to 1941, when it was invaded by the Axis powers during World War II, which provided support to the Ustaše (founded in 1929), which conducted a genocidal campaign against Serbs, Jews and Roma inside its territory and the Chetniks, who also conducted their own campaign of ethnic cleansing and genocide towards ethnic Croats and Bosniaks, while also supporting the reinstating of the Serbian royals. In 1945, the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY) was established under Josip Broz Tito,[5] who maintained a strongly authoritarian leadership that suppressed nationalism.[28] After Tito's death in 1980, relations among the six republics of the SFRY deteriorated. Slovenia and Croatia desired greater autonomy within the Yugoslav confederation, while Serbia sought to strengthen federal authority. As it became clearer that there was no solution agreeable to all parties, Slovenia and Croatia moved toward secession. Although tensions in Yugoslavia had been mounting since the early 1980s, it was 1990 that proved decisive. In the midst of economic hardship, Yugoslavia was facing rising nationalism among its various ethnic groups. By the early 1990s, there was no effective authority at the federal level. The Federal Presidency consisted of the representatives of the six republics, two provinces, and the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA). The communist leadership was divided along national lines.[29]

The representatives of Vojvodina, Kosovo and Montenegro were replaced with loyalists of the President of Serbia, Slobodan Milošević. Serbia secured four out of eight federal presidency votes[31] and was able to heavily influence decision-making at the federal level, since all the other Yugoslav republics only had one vote. While Slovenia and Croatia wanted to allow a multi-party system, Serbia, led by Milošević, demanded an even more centralized federation and Serbia's dominant role in it.[29] At the 14th Extraordinary Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia in January 1990, the Serbian-dominated assembly agreed to abolish the single-party system; however, Slobodan Milošević, the head of the Serbian Party branch (League of Communists of Serbia) used his influence to block and vote-down all other proposals from the Croatian and Slovene party delegates. This prompted the Croatian and Slovene delegations to walk out and thus the break-up of the party,[32] a symbolic event representing the end of "brotherhood and unity".

Upon Croatia and Slovenia declaring independence in 1991, the Yugoslav federal government attempted to forcibly halt the impending breakup of the country, with Yugoslav Prime Minister Ante Marković declaring the secessions of Slovenia and Croatia to be illegal and contrary to the constitution of Yugoslavia, and declared support for the Yugoslav People's Army to secure the integral unity of Yugoslavia.[33]

According to Stephen A. Hart, author of Partisans: War in the Balkans 1941–1945, the ethnically mixed region of Dalmatia held close and amicable relations between the Croats and Serbs who lived there in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Many early proponents of a united Yugoslavia came from this region, such as Ante Trumbić, a Croat from Dalmatia. However, by the time of the outbreak of the Yugoslav Wars, any hospitable relations between Croats and Serbs in Dalmatia had broken down, with Dalmatian Serbs fighting on the side of the Republic of Serbian Krajina.

Even though the policies throughout the entire socialist period of Yugoslavia seemed to have been the same (namely that all Serbs should live in one state), Dejan Guzina argues that "different contexts in each of the subperiods of socialist Serbia and Yugoslavia yielded entirely different results (e.g., in favor of Yugoslavia, or in favor of a Greater Serbia)". He assumes that the Serbian policy changed from conservative–socialist at the beginning to xenophobic nationalist in the late 1980s and 1990s.[34]

Wars

Ten-Day War (1991)

The first of the conflicts, known as the Ten-Day War, was initiated by the JNA (Yugoslav People's Army) on 26 June 1991 after the secession of Slovenia from the federation on 25 June 1991.[35][36]

Initially, the federal government ordered the Yugoslav People's Army to secure border crossings in Slovenia. Slovenian police and Slovenian Territorial Defence blockaded barracks and roads, leading to stand-offs and limited skirmishes around the republic. After several dozen casualties, the limited conflict was stopped through negotiation at Brioni on 7 July 1991, when Slovenia and Croatia agreed to a three-month moratorium on secession. The Federal army completely withdrew from Slovenia by 26 October 1991.

Croatian War of Independence (1991–1995)

.jpg)

Fighting in Croatia had begun weeks prior to the Ten-Day War in Slovenia. The Croatian War of Independence began when Serbs in Croatia, who were opposed to Croatian independence, announced their secession from Croatia.

After the 1990 parliamentary elections in Croatia, Franjo Tuđman came to power and became the first President of Croatia. He promoted nationalist policies and had a primary goal of the establishment of an independent Croatia. The new government proposed constitutional changes, reinstated the traditional Croatian flag and coat of arms and removed the term "Socialist" from the title of the republic.[37] In an attempt to counter changes made to the constitution, local Serb politicians organized a referendum on "Serb sovereignty and autonomy" in August 1990. Their boycott escalated into an insurrection in areas populated by ethnic Serbs, mostly around Knin, known as the Log Revolution.[38] Local police in Knin sided with the growing Serbian insurgency, while many government employees, mostly in police where commanding positions were mainly held by Serbs and Communists, lost their jobs.[39] The new Croatian constitution was ratified in December 1990, when the Serb National Council proclaimed the SAO Krajina.[40]

Ethnic tensions rose, fueled by propaganda in both Croatia and Serbia. On 2 May 1991, one of the first armed clashes between Serb paramilitaries and Croatian police occurred in the Battle of Borovo Selo.[41] On 19 May an independence referendum was held, which was largely boycotted by Croatian Serbs, and the majority voted in favour of the independence of Croatia.[42][40] Croatia declared independence and dissolved its association with Yugoslavia on 25 June 1991. Due to the Brioni Agreement, a three-month moratorium was placed on the implementation of the decision that ended on 8 October.[43]

The armed incidents of early 1991 escalated into an all-out war over the summer, with fronts formed around the areas of the breakaway SAO Krajina. The JNA had disarmed the Territorial Units of Slovenia and Croatia prior to the declaration of independence, at the behest of Serbian President Slobodan Milošević.[44][45] This was aggravated further by an arms embargo, imposed by the UN on Yugoslavia. The JNA was ostensibly ideologically unitarian, but its officer corps was predominantly staffed by Serbs or Montenegrins (70 percent).[46] As a result, the JNA opposed Croatian independence and sided with the Croatian Serb rebels. The Croatian Serb rebels were unaffected by the embargo as they had the support of and access to supplies of the JNA. By mid-July 1991, the JNA moved an estimated 70,000 troops to Croatia. The fighting rapidly escalated, eventually spanning hundreds of square kilometers from western Slavonia through Banija to Dalmatia.[47]

Border regions faced direct attacks from forces within Serbia and Montenegro. In August 1991, the Battle of Vukovar began, where fierce fighting took place with around 1,800 Croat fighters blocking JNA's advance into Slavonia. By the end of October, the town was almost completely devastated from land shelling and air bombardment.[48] The Siege of Dubrovnik started in October with the shelling of UNESCO world heritage site Dubrovnik, where the international press was criticised for focusing on the city's architectural heritage, instead of reporting the destruction of Vukovar in which many civilians were killed.[49] On 18 November 1991 the battle of Vukovar ended after the city ran out of ammunition. The Ovčara massacre occurred shortly after Vukovar's capture by the JNA.[50] Meanwhile, control over central Croatia was seized by Croatian Serb forces in conjunction with the JNA Corps from Bosnia and Herzegovina, under the leadership of Ratko Mladić.[51]

In January 1992, the Vance Plan proclaimed UN controlled (UNPA) zones for Serbs in territory claimed by Serbian rebels as the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK) and brought an end to major military operations, though sporadic artillery attacks on Croatian cities and occasional intrusions of Croatian forces into UNPA zones continued until 1995. The fighting in Croatia ended in mid-1995, after Operation Flash and Operation Storm. At the end of these operations, Croatia had reclaimed all of its territory except the UNPA Sector East portion of Slavonia, bordering Serbia. Most of the Serb population in the reclaimed areas became refugees, and these operations led to war crimes trials by the ICTY against elements of the Croatian military leadership in the Trial of Gotovina et al. Generals Ante Gotovina and Mladen Markač were found guilty of "war crimes and crimes against humanity" in the first instance verdict,[52] but were acquitted on appeal in 2012.[53] The areas of "Sector East", unaffected by the Croatian military operations, came under UN administration (UNTAES), and were reintegrated to Croatia in 1998 under the terms of the Erdut Agreement.[54]

In 2007, Milan Martić, former president of RSK, was sentenced to 35 years imprisonment as part of a joint criminal enterprise against the non-Serb population of Croatia.[55] Milan Babić, the first President of RSK, pleaded guilty and was sentenced by the ICTY to 13 years in prison.[56]

Bosnian War (1992–1995)

In 1992, conflict engulfed Bosnia and Herzegovina. The war was predominantly a territorial conflict between the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina chiefly supported by Bosniaks, the self-proclaimed Bosnian Serb entity Republika Srpska, and the self-proclaimed Herzeg-Bosnia, who were led and supplied by Serbia and Croatia respectively, reportedly with a goal of the partition of Bosnia.

The Yugoslav armed forces had disintegrated into a largely Serb-dominated military force. Opposed to the Bosnian-majority led government's agenda for independence, and along with other armed nationalist Serb militant forces, the JNA attempted to prevent Bosnian citizens from voting in the 1992 referendum on independence.[57] This did not succeed in persuading people not to vote and instead the intimidating atmosphere combined with a Serb boycott of the vote resulted in a resounding 99% vote in support for independence.[57]

On 19 June 1992, the war in Bosnia broke out, though the Siege of Sarajevo had already begun in April after Bosnia and Herzegovina had declared independence. The conflict, typified by the years-long Sarajevo siege and Srebrenica, was by far the bloodiest and most widely covered of the Yugoslav wars. Bosnia's Serb faction led by ultra-nationalist Radovan Karadžić promised independence for all Serb areas of Bosnia from the majority-Bosniak government of Bosnia. To link the disjointed parts of territories populated by Serbs and areas claimed by Serbs, Karadžić pursued an agenda of systematic ethnic cleansing primarily against Bosnians through massacre and forced removal of Bosniak populations.[58]

At the end of 1992, tensions between Bosnian Croats and Bosniaks rose and their collaboration fell apart. In January 1993, the two former allies engaged in open conflict, resulting in the Croat–Bosniak War.[59] In 1994 the US brokered peace between Croatian forces and the Bosnian Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina with the Washington Agreement. After the successful Flash and Storm operations, the Croatian Army and the combined Bosnian and Croat forces of Bosnia and Herzegovina, conducted an operation codenamed Operation Mistral to push back Bosnian Serb military gains.[60]

Together with NATO air strikes on the Bosnian Serbs, the successes on the ground put pressure on the Serbs to come to the negotiating table. Pressure was put on all sides to stick to the cease-fire and negotiate an end to the war in Bosnia. The war ended with the signing of the Dayton Agreement on 14 December 1995, with the formation of Republika Srpska as an entity within Bosnia and Herzegovina being the resolution for Bosnian Serb demands.

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in the United States reported in April 1995 that 90 percent of all the atrocities in the Yugoslav wars up to that point had been committed by Serb militants.[61] Most of these atrocities occurred in Bosnia. In 2004, the ICTY ruled that the Srebrenica massacre constituted genocide.[62] In May 2013, in a first-instance verdict, the ICTY convicted six Herzeg-Bosnia Officials for their participation in a joint criminal enterprise against Muslim population in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[63] On 24 March 2016, Radovan Karadžić, former president of Republika Srpska, was found guilty of genocide in Srebrenica, war crimes and crimes against humanity and sentenced to 40 years' imprisonment. On 22 November 2017, Ratko Mladić, former Chief of Staff of the Army of the Republika Srpska, was sentenced to life in prison by ICTY for 10 charges, one of genocide, five of crimes against humanity and four of violations of the laws or customs of war.

Kosovo War (1998–1999)

After September 1990 when the 1974 Yugoslav Constitution had been unilaterally repealed by the Socialist Republic of Serbia, Kosovo's autonomy suffered and so the region was faced with state organized oppression: from the early 1990s, Albanian language radio and television were restricted and newspapers shut down. Kosovar Albanians were fired in large numbers from public enterprises and institutions, including banks, hospitals, the post office and schools.[64] In June 1991 the University of Priština assembly and several faculty councils were dissolved and replaced by Serbs. Kosovar Albanian teachers were prevented from entering school premises for the new school year beginning in September 1991, forcing students to study at home.[64]

Later, Kosovar Albanians started an insurgency against Belgrade when the Kosovo Liberation Army was founded in 1996. Armed clashes between the two sides broke out in early 1998. A NATO-facilitated ceasefire was signed on 15 October, but both sides broke it two months later and fighting resumed. When the killing of 45 Kosovar Albanians in the Račak massacre was reported in January 1999, NATO decided that the conflict could only be settled by introducing a military peacekeeping force to forcibly restrain the two sides. After the Rambouillet Accords broke down on 23 March with Yugoslav rejection of an external peacekeeping force, NATO prepared to install the peacekeepers by force. The NATO bombing of Yugoslavia followed, an intervention against Serbian forces with a mainly bombing campaign, under the command of General Wesley Clark. Hostilities ended 2½ months later with the Kumanovo Agreement. Kosovo was placed under the governmental control of the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo and the military protection of Kosovo Force (KFOR). The 15-month war had left thousands of civilians killed on both sides and over a million displaced.[65]

Insurgency in the Preševo Valley (1999–2001)

The Insurgency in the Preševo Valley was an armed conflict between the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the ethnic-Albanian insurgents[66][67][68] of the Liberation Army of Preševo, Medveđa and Bujanovac (UÇPMB).[69] There were instances during the conflict in which the Yugoslav government requested KFOR support in suppressing UÇPMB attacks since they could only use lightly armed military forces as part of the Kumanovo Treaty that ended the Kosovo War, which created a buffer zone so the bulk of the Yugoslav armed forces could not enter.[70]

Yugoslav president Vojislav Koštunica warned that fresh fighting would erupt if KFOR units did not act to prevent the attacks that were coming from the UÇPMB.[71]

Insurgency in the Republic of Macedonia (2001)

The insurgency in the Republic of Macedonia was an armed conflict in Tetovo which began when the ethnic Albanian National Liberation Army (NLA) militant group began attacking the security forces of the Republic of Macedonia at the beginning of February 2001, and ended with the Ohrid Agreement. The goal of the NLA was to give greater rights and autonomy to the country's Albanian minority, who make up 25.2% (54.7% of the population in Tetovo) of the population of Macedonia.[72][73] There were also claims that the group ultimately wished to see Albanian-majority areas secede from the country,[74] although high-ranking NLA members have denied this.[72]

Arms embargo

The United Nations Security Council had imposed an arms embargo in September 1991.[75] Nevertheless, various states had been engaged in, or facilitated, arms sales to the warring factions.[76] In 2012, Chile convicted nine people, including two retired generals, for their part in arms sales.[77]

After the fighting ended, millions of weapons were left with civilians who held on to them in case violence should resurface. These weapons later turned up on the black arms market of Europe.[78]

War crimes

Genocide

It is widely considered that mass murders against Bosniaks in Bosnia and Herzegovina escalated into genocide. On 18 December 1992, the United Nations General Assembly issued resolution 47/121 condemning "aggressive acts by the Serbian and Montenegrin forces to acquire more territories by force" and called such ethnic cleansing "a form of genocide".[79] In its report published on the 1 January 1993, Helsinki Watch was one of the first civil rights organisations that warned that "the extent of the violence and its selective nature along ethnic and religious lines suggest crimes of genocidal character against Muslim and, to a lesser extent, Croatian populations in Bosnia-Hercegovina".[80]

A trial took place before the International Court of Justice, following a 1993 suit by Bosnia and Herzegovina against Serbia and Montenegro alleging genocide. The ICJ ruling of 26 February 2007 indirectly determined the war's nature to be international, though clearing Serbia of direct responsibility for the genocide committed by the forces of Republika Srpska. The ICJ concluded, however, that Serbia failed to prevent genocide committed by Serb forces and failed to punish those responsible, and bring them to justice.[81] A telegram sent to the White House on 8 February 1994 and penned by U.S. Ambassador to Croatia, Peter W. Galbraith, stated that genocide was occurring. The telegram cited "constant and indiscriminate shelling and gunfire" of Sarajevo by Karadzic's Yugoslav People Army; the harassment of minority groups in Northern Bosnia "in an attempt to force them to leave"; and the use of detainees "to do dangerous work on the front lines" as evidence that genocide was being committed.[82] In 2005, the United States Congress passed a resolution declaring that "the Serbian policies of aggression and ethnic cleansing meet the terms defining genocide".[83]

Despite the evidence of many kinds of war crimes conducted simultaneously by different Serb forces in different parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina, especially in Bijeljina, Sarajevo, Prijedor, Zvornik, Banja Luka, Višegrad and Foča, the judges ruled that the criteria for genocide with the specific intent (dolus specialis) to destroy Bosnian Muslims were met only in Srebrenica or Eastern Bosnia in 1995.[81] The court concluded that other crimes, outside Srebrenica, committed during the 1992–1995 war, may amount to crimes against humanity according to the international law, but that these acts did not, in themselves, constitute genocide per se.[84]

The crime of genocide in the Srebrenica enclave was confirmed in several guilty verdicts handed down by the ICTY, most notably in the conviction of the Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadžić.[85]

Ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing was a common phenomenon in the wars in Croatia, Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina. This entailed intimidation, forced expulsion, or killing of the unwanted ethnic group as well as the destruction of the places of worship, cemeteries and cultural and historical buildings of that ethnic group in order to alter the population composition of an area in the favour of another ethnic group which would become the majority. These examples of territorial nationalism and territorial aspirations are part of the goal of an ethno-state.[86]

According to numerous ICTY verdicts and indictments, Serb[87][88][89] and Croat[90] forces performed ethnic cleansing of their territories planned by their political leadership to create ethnically pure states (Republika Srpska and Republic of Serbian Krajina by the Serbs; and Herzeg-Bosnia by the Croats).

According to the ICTY, Serb forces deported at least 80–100,000 Croats in Croatia in 1991–92[91] and at least 700,000 Albanians in Kosovo in 1999.[92] Further hundreds of thousands of Muslims were forced out of their homes by the Serb forces in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[93] By one estimate, the Serb forces drove at least 700,000 Bosnian Muslims from the area of Bosnia under their control.[94]

War rape

War rape occurred as a matter of official orders as part of ethnic cleansing, to displace the targeted ethnic group.[95] According to the Tresnjevka Women's Group, more than 35,000 women and children were held in such Serb-run "rape camps".[96][97][98] Dragoljub Kunarac, Radomir Kovač, and Zoran Vuković were convicted of crimes against humanity for rape, torture, and enslavement committed during the Foča massacres.[99]

The evidence of the magnitude of rape in Bosnia and Herzegovina prompted the ICTY to deal openly with these abuses.[100] Reports of sexual violence during the Bosnian War (1992–1995) and Kosovo War (1998–1999) perpetrated by the Serbian regular and irregular forces have been described as "especially alarming".[96] The NATO-led Kosovo Force documented rapes of Albanian, Roma and Serbian women by both Serbs and members of the Kosovo Liberation Army.[101]

Others have estimated that during the Bosnian War between 20,000 and 50,000 women, mainly Bosniak, were raped.[102][103] There are few reports of rape and sexual assault between members of the same ethnic group.[104]

War rape in the Yugoslav Wars has often been characterized as a crime against humanity. Rape perpetrated by Serb forces served to destroy cultural and social ties of the victims and their communities.[105] Serbian policies allegedly urged soldiers to rape Bosniak women until they became pregnant as an attempt towards ethnic cleansing. Serbian soldiers hoped to force Bosniak women to carry Serbian children through repeated rape.[106] Often Bosniak women were held in captivity for an extended period of time and only released slightly before the birth of a child conceived of rape. The systematic rape of Bosniak women may have carried further-reaching repercussions than the initial displacement of rape victims. Stress, caused by the trauma of rape, coupled with the lack of access to reproductive health care often experienced by displaced peoples, lead to serious health risks for victimized women.[107]

During the Kosovo War thousands of Kosovo Albanian women and girls became victims of sexual violence. War rape was used as a weapon of war and an instrument of systematic ethnic cleansing; rape was used to terrorize the civilian population, extort money from families, and force people to flee their homes. According to a report by the Human Rights Watch group in 2000, rape in the Kosovo War can generally be subdivided into three categories: rapes in women's homes, rapes during flight, and rapes in detention.[108][109] The majority of the perpetrators were Serbian paramilitaries, but also included Serbian special police or Yugoslav army soldiers. Virtually all of the sexual assaults Human Rights Watch documented were gang rapes involving at least two perpetrators.[108][109] Since the end of the war, rapes of Serbian, Albanian, and Roma women by ethnic Albanians — sometimes by members of the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) – have been documented.[108][109] Rapes occurred frequently in the presence, and with the acquiescence, of military officers. Soldiers, police, and paramilitaries often raped their victims in the full view of numerous witnesses.[95]

Consequences

Casualties

Some estimates put the number of killed in the Yugoslav Wars at 140,000.[1] The Humanitarian Law Center estimates that in the conflicts in former Yugoslav republics at least 130,000 people lost their lives.[2] Slovenia's involvement in the conflicts was brief, thus avoiding higher casualties, and around 70 people were killed in its ten-day conflict. The War in Croatia left an estimated 20,000 people dead. Bosnia and Herzegovina suffered the heaviest burden of the fighting: around 100,000 people were killed in the war. In the Kosovo conflict, around 13,500 were killed. Overall, no less than 133,000 people were killed in the post-Yugoslav conflicts in the 90s.[110] The highest death toll was in Sarajevo: with around 14,000 killed during the siege,[110] the city lost almost as many people as the entire war in Kosovo.

In relative and absolute numbers, Bosniaks suffered the heaviest losses: 64,036 of their people were killed, which represents a death toll of over 3% of their entire ethnic group.[111] They experienced the worst plight in the Srebrenica massacre, where the mortality rate of the Bosniak men (irrespective of their age or civilian status) reached 33% in July 1995.[112] The share of Bosniaks among all the civilian fatalities during the Bosnian War was around 83%, rising to almost 95% in Eastern Bosnia.[113]

During the War in Croatia, 43.4% of the killed on the Croatian side were civilians.[114]

Internally displaced and refugees

It is estimated that the wars in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo produced about 2.4 million refugees and an additional 2 million internally displaced persons.[115]

The war in Bosnia and Herzegovina caused 2.2 million refugees or displaced, of which over half were Bosniaks.[116] Up until 2001, there were still 650,000 displaced Bosniaks, while 200,000 left the country permanently.[116]

The Kosovo War caused 862,979 Albanian refugees who were either expelled from the Serb forces or fled from the battle front.[117] In addition, several hundreds of thousands were internally displaced, which means that, according to the OSCE, almost 90% of all Albanians were displaced from their homes in Kosovo by June 1999.[118] After the end of the war, Albanians returned, but over 200,000 Serbs, Romani and other non-Albanians fled Kosovo. By the end of 2000, Serbia thus became the host of 700,000 Serb refugees or internally displaced from Kosovo, Croatia and Bosnia.[119]

From the perspective of asylum for internally displaced or refugees, Croatia took the brunt of the crisis. According to some sources, in 1992 Croatia was the host to almost 750,000 refugees or internally displaced, which represents a quota of almost 16% of its population of 4.7 million inhabitants: these figures included 420 to 450,000 Bosnian refugees, 35,000 refugees from Serbia (mostly from Vojvodina and Kosovo) while a further 265,000 persons from other parts of Croatia itself were internally displaced. This would be equivalent of Germany being a host to 10 million displaced people or France to 8 million people. [120] Official UNHCR data indicate that Croatia was the host to 287,000 refugees and 344,000 internally displaced in 1993. This is a ratio of 64.7 refugees per 1000 inhabitants.[121] In its 1992 report, UNHCR placed Croatia #7 on its list of 50 most refugee burdened countries: it registered 316 thousand refugees, which is a ratio of 15:1 relative to its total population.[122] Together with those internally displaced, Croatia was the host to at least 648,000 people in need of an accommodation in 1992.[123] In comparison, Macedonia had 10.5 refugees per 1000 inhabitants in 1999.[124] Slovenia was the host to 45,000 refugees in 1993, which is 22.7 refugees per 1000 inhabitants.[125] Serbia and Montenegro were the host to 479,111 refugees in 1993, which is a ratio of 45.5 refugees per 1000 inhabitants. By 1998 this grew to 502,037 refugees (or 47.7 refugees per 1000 inhabitants). By 2000 the number of refugees fell to 484,391 persons, but the number of internally displaced grew to 267,500, or a combined total of 751,891 persons who were displaced and in need of an accommodation.[126]

| Country, region | Albanians | Bosniaks | Croats | Serbs | Others (Hungarians, Gorani, Romani) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Croatia | — | — | 247,000[127] | 300,000[128] | — |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | — | 1,270,000[129] | 490,000[129] | 540,000[129] | — |

| Kosovo | 1,200,000[130]— 1,450,000[118] | — | 35,000[120]— 40.000[131] | 143,000[132] | 67,000[132] |

| Vojvodina, Sandžak | — | 30,000— 40,000[133] | — | 60.000[131] | |

| Total | ~1,200,000— 1,450,000 | ~1,300,000— 1,310,000 | ~772,000— 777,000 | ~983,000 | ~127,000 |

Material damage

Material and economic damages brought by the conflicts were catastrophic. Bosnia and Herzegovina had a GDP of between $8–9 billion before the war. The government estimated the overall war damages at $50–$70 billion. It also registered a GDP decline of 75% after the war.[134] Some 60% of the housing in the country has been either damaged or destroyed, which proved a problem when trying to bring all the refugees back home.[135] Bosnia also became the most landmine contaminated country of Europe: 1820 km2 of its territory were contaminated with these explosives, which represent 3.6% of its land surface. Between 3 and 6 million landmines were scattered throughout Bosnia. 5,000 people died from them, of which 1,520 after the war.[136]

In 1999, the Croatian Parliament passed a bill estimating war damages of the country at $37 billion.[137] The government alleges that between 1991 and April 1993 an estimated total of 210,000 buildings in Croatia (including schools, hospitals and refugee camps) were either damaged or destroyed from shelling by the Republic of Serbian Krajina and the JNA forces. Cities affected by the shelling were Karlovac, Gospić, Ogulin, Zadar, Biograd and others.[138] The Croatian government also acknowledged that 7,489 buildings belonging to Croatian Serbs were damaged or destroyed by explosives, arson or other deliberate means by the end of 1992. From January to March 1993 another 220 buildings were also damaged or destroyed. Criminal charges were brought against 126 Croats for such acts.[139]

Sanctions against FR Yugoslavia createad a hyperinflation of 300 million percent of the Yugoslav dinar. By 1995, almost 1 million workers lost their jobs while the gross domestic product has fallen 55 percent since 1989.[140] The 1999 NATO bombing of Serbia resulted in additional damages. One of the most severe was the bombing of the Pančevo petrochemical factory, which caused the release of 80,000 tonnes of burning fuel into the environment.[141] Approximately 31,000 rounds of depleted Uranium ammuniton was used during this bombing.[142]

ICTY/MICT

.jpg)

The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) was a body of the U.N. established to prosecute serious crimes committed during the Yugoslav Wars, and to try their perpetrators. The tribunal was an ad hoc court located in The Hague, Netherlands. One of the most prominent trials involved ex-Serbian President Slobodan Milošević, who was in 2002 indicted on 66 counts of crimes against humanity, war crimes and genocide allegedly committed in wars in Kosovo, Bosnia and Croatia.[143] His trial remained incomplete since he died in 2006, before a verdict was reached.[144] Nonetheless, ICTY's trial "helped to delegitimize Milosevic's leadership", as one scholar put it.[145]

Several convictions were handed over by the ICTY and its successor, the Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals (MICT). One notable verdict was against ex-Bosnian Serb leader, Radovan Karadžić, who was convicted for genocide in Bosnia.[146] On 22 November 2017, general Ratko Mladić was sentenced to a life in prison.[147] Other important convictions included those of ultranationalist Vojislav Šešelj,[148][149] paramilitary leader Milan Lukić,[150] Bosnian Serb politician Momčilo Krajišnik,[151] Bosnian Serb general Stanislav Galić, who was convicted for terror during the siege of Sarajevo,[152] the former Assistant Minister of the Serbian Ministry of Internal Affairs and Chief of its Public Security Department, Vlastimir Đorđević, who was convicted for crimes in Kosovo,[153] ex-JNA commander Mile Mrkšić[154][155] and Croatian Serb leader Milan Martić.[156]

Several Croats, Bosniaks and Albanians were convicted for crimes, as well, including ex-Herzegovina Croat leader Jadranko Prlić and commander Slobodan Praljak,[157] Bosnian Croat military commander Mladen Naletilić,[158] ex-Bosnian Army commander Enver Hadžihasanović[159] and ex-Kosovo commander Haradin Bala.[160]

Timeline of the Yugoslav Wars

1990

- Log Revolution. SAO Krajina is proclaimed over an indefinite area of Croatia.

1991

- Slovenia and Croatia declare independence in June, Macedonia in September. War in Slovenia lasts ten days, and results in dozens of fatalities. The Yugoslav army leaves Slovenia defeated, but supports rebel Serb forces in Croatia. The Croatian War of Independence begins in Croatia. Serb areas in Croatia declare independence, but are recognized only by Belgrade.

- Vukovar is devastated by bombardments and shelling, and other cities such as Dubrovnik, Karlovac and Osijek sustain extensive damage.[161] Refugees from war zones overwhelm Croatia, while Europe is slow to accept refugees.

- In Croatia, about 250,000 Croats and other non-Serbs forced from their homes or fled the violence.[162]

1992

- Vance Plan signed, creating four United Nations Protection Force zones for Serbs and ending large-scale fighting in Croatia.

- Bosnia declares independence. Bosnian war begins with the Bosnian Serb military leadership, most notably Ratko Mladić, trying to create a new, separate Serb state, Republika Srpska, through which they would conquer as much of Bosnia as possible for the vision of a Greater Serbia.[163]

- Federal Republic of Yugoslavia proclaimed, consisting of Serbia and Montenegro, the two remaining republics.

- United Nations impose sanctions against FR Yugoslavia for its support of the unrecognized Republic of Serbian Krajina in Croatia and Republika Srpska in Bosnia.[164] In May 1992, Slovenia, Croatia and Bosnia become UN members. FR Yugoslavia claims being sole legal heir to SFRY, which is disputed by other republics. UN envoys agree that Yugoslavia had 'dissolved into constituent republics'.

- The Yugoslav army retreats from Bosnia, but leaves its weapons to the army of Republika Srpska, which attacks poorly armed Bosnian cities of Zvornik, Kotor Varoš, Prijedor, Foča, Višegrad, Doboj. Prijedor ethnic cleansing and siege of Sarajevo start. Hundreds of thousands of non-Serbian refugees.

- Bosniak-Croat conflict begins in Bosnia.

1993

- Fighting begins in the Bihać region between Bosnian Government forces loyal to Alija Izetbegović, and Bosniaks loyal to Fikret Abdić, also supported by the Serbs.

- Sanctions in FR Yugoslavia, now isolated, create hyperinflation of 300 million percent of the Yugoslav dinar.[140]

- Ahmići massacre: the Croat forces kill over a hundred Bosnian Muslims.

- Battle of Mostar. The Stari Most (The Old Bridge) in Mostar, built in 1566, was destroyed by Croatian HVO forces.[165] It was rebuilt in 2003.

1994

- Markale market shelling in Sarajevo.

- Peace treaty between Bosniaks and Croats arbitrated by the United States, Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina formed.

- FR Yugoslavia starts slowly suspending its financial and military support for Republika Srpska.[166]

1995

- Srebrenica massacre reported. 8,000 Bosniaks killed by Serb forces.[85]

- Croatia launches Operation Flash, recapturing a part of its territory, but tens of thousands of Serb civilians flee from the area. The RSK responds with the Zagreb rocket attack.

- Croatia launches Operation Storm, reclaiming all UNPA zones except Eastern Slavonia, and resulting in exodus of 150,000–200,000 Serbs from the zones. Yugoslav forces do not intervene. War in Croatia ends.

- NATO launches a series of air strikes on Bosnian Serb artillery and other military targets. Croatian and Bosnian army start a joint offensive against Republika Srpska.

- Dayton Agreement signed in Paris. War in Bosnia and Herzegovina ends. Aftermath of war is over 100,000 killed and missing and two million people internally displaced or refugees.[167]

1996

- FR Yugoslavia recognizes Croatia and Bosnia & Herzegovina.

- Fighting breaks out in Kosovo between Albanians rebels and FR Yugoslav authorities.

- Following allegations of fraud in local elections, tens of thousands of Serbs demonstrate in Belgrade against the Milošević government for three months.[168]

1998

- Eastern Slavonia peacefully reintegrated into Croatia, following a gradual three-year handover of power.

- Fighting in Kosovo gradually escalates between Albanians demanding independence and the state.

1999

- Račak massacre, Rambouillet talks fail. NATO starts a military campaign in Kosovo and bombards FR Yugoslavia in Operation Allied Force.[169]

- Following Milošević's signing of an agreement, control of Kosovo is handed to the United Nations, but still remains a part of Yugoslavia's federation. After losing wars in Croatia, Bosnia and Kosovo, numerous Serbs leave those regions to find refuge in remainder of Serbia. In 1999, Serbia was host to some 700,000 Serb refugees or internally displaced.[119]

- Fresh fighting erupts between Albanians and Yugoslav security forces in Albanian populated areas outside of Kosovo, with the intent of joining three municipalities to Kosovo (Preševo, Bujanovac and Medveđa).

- Franjo Tuđman dies. Shortly after, his party loses the elections.

2000

- Slobodan Milošević is voted out of office, and Vojislav Koštunica becomes the new president of Yugoslavia. With Milošević ousted and a new government in place, FR Yugoslavia restores ties with the west. The political and economic sanctions are suspended in total, and FRY is reinstated in many political and economic organizations, as well as becoming a candidate for other collaborative efforts.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Some historians only narrow the conflicts to Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo in the 1990s.[4] Others also include the Preševo Valley Conflict and Insurgency in Macedonia (2001).

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Transitional Justice in the Former Yugoslavia". International Center for Transitional Justice. 1 January 2009. Retrieved 8 September 2009.

- 1 2 3 "About us". Humanitarian Law Center. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ↑ "Transitional Justice in the Former Yugoslavia". ICJT. International Center for Transitional Justice. 1 January 2009.

- ↑ Shaw 2013, p. 132.

- 1 2 3 Judah, Tim (17 February 2011). "Yugoslavia: 1918–2003". BBC. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ↑ Finlan (2004), p. 8

- ↑ Naimark (2003), p. xvii.

- ↑ Armatta, Judith (2010), Twilight of Impunity: The War Crimes Trial of Slobodan Milosević, Duke University Press, p. 121

- ↑ Annex IV – II. The politics of creating a Greater Serbia: nationalism, fear and repression

- ↑ Jannsens, Jelle (5 February 2015). "State-building in Kosovo. A plural policing perspective". Maklu. p. 53. ISBN 978-90-466-0749-7.

- ↑ Totten, Samuel; Bartrop, Paul R. (2008). "Dictionary of Genocide". with contributions by Steven Leonard Jacobs. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 249. ISBN 978-0-313-32967-8.

- ↑ Sullivan, Colleen (14 September 2014). "Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA)". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Karon, Tony (9 March 2001). "Albanian Insurgents Keep NATO Forces Busy". TIME.

- ↑ Phillips, David L. (2012). "Liberating Kosovo: Coercive Diplomacy and U.S. Intervention". in cooperation with the Future of Diplomacy Project, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. The MIT Press. p. 69.

- ↑ International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (29 May 2013). "Prlic et al. judgement vol.6 2013" (PDF). United Nations. p. 383.

- ↑ Gow, James (2003). "The Serbian Project and Its Adversaries: A Strategy of War Crimes". C. Hurst & Co. p. 229. ISBN 9781850654995.

- ↑ van Meurs, Wim, ed. (11 November 2013). "Prospects and Risks Beyond EU Enlargement: Southeastern Europe: Weak States and Strong International Support". Springer Science & Business Media. p. 168.

- ↑ Thomas, Raju G. C., ed. (2003). "Yugoslavia Unraveled: Sovereignty, Self-Determination, Intervention". Lexington Books. p. 10.

- ↑ Mahmutćehajić, Rusmir (1 February 2012). "Sarajevo Essays: Politics, Ideology, and Tradition". State University of New York Press. p. 120.

- ↑ Bosnia Genocide, United Human Rights Council, archived from the original on 13 April 2015, retrieved 13 April 2015

- ↑ United Nations Security Council Resolution 827. S/RES/827(1993) 25 May 1993.

- ↑ Tabeau, Ewa (15 January 2009). "Casualties of the 1990s wars in the former Yugoslavia (1991–1999)" (PDF). Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia.

- ↑ Glenny (1996), p. 250

- ↑ Bideleux & Jeffries (2007), p. 429

- ↑ "Serbia and Kosovo reach EU-brokered landmark accord". BBC. 19 April 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- ↑ Hart, Stephen A. (17 February 2011). "Partisans: War in the Balkans 1941–1945". BBC History. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- 1 2 Gagnon (2004), p. 5

- ↑ Annex III – The Balkan wars and the world wars

- 1 2 Annex IV – Prelude to the breakup

- ↑ Decision of the ICTY Appeals Chamber; 18 April 2002; Reasons for the Decision on Prosecution Interlocutory Appeal from Refusal to Order Joinder; Paragraph 8

- ↑ Brown & Karim (1995), p. 116

- ↑ "Milosevic's Yugoslavia: Communism Crumbles". Milosevic's Yugoslavia. BBC News.

- ↑ Cohen & Dragović-Saso (2008), p. 323

- ↑ Guzina 2003, p. 91.

- ↑ Race, Helena (2005). "Dan prej" – 26. junij 1991: diplomsko delo ["A Day Before" – 26 June 1991 (diploma thesis)] (PDF) (in Slovenian). Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ljubljana. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ↑ Prunk, Janko (2001). "Path to Slovene State". Public Relations and Media Office, Government of the Republic of Slovenia. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ↑ Tanner 2001, p. 229.

- ↑ Tanner 2001, p. 233.

- ↑ Ramet 2010, p. 262.

- 1 2 Goldstein 1999, p. 222.

- ↑ Ramet 2010, p. 119.

- ↑ Sudetic, Chuck (20 May 1991). "Croatia Votes for Sovereignty and Confederation". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ↑ Goldstein 1999, p. 226.

- ↑ Glaurdić, Josip (2011). The Hour of Europe: Western Powers and the Breakup of Yugoslavia. Yale University Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-300-16645-3.

- ↑ Annex III – The Conflict in Slovenia

- ↑ Annex III – General structure of the Yugoslav armed forces

- ↑ Annex III – Forces operating in Croatia

- ↑ Tanner 2001, p. 256.

- ↑ Pearson, Joseph (2010). "Dubrovnik's Artistic Patrimony, and its Role in War Reporting (1991)". European History Quarterly. 40 (2): 197–216. doi:10.1177/0265691410358937.

- ↑ Ramet 2010, p. 263.

- ↑ "Profile: Ratko Mladic, Bosnian Serb army chief". BBC News. 31 July 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ↑ "Judgement Summary for Gotovina et al" (PDF). The Hague: International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 15 April 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ↑ "Appeals Judgement Summary for Ante Gotovina and Mladen Markač" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 16 November 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ↑ "The Erdut Agreement" (PDF). United States Institute of Peace. 12 November 1995. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ↑ "Milan Martić sentenced to 35 years for crimes against humanity and war crimes". International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 12 June 2007. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ↑ "Milan Babić". International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- 1 2 Meštrović (1996), p. 36.

- ↑ Meštrović (1996), pg. 7.

- ↑ "Prosecutor v. Rasim Delić Judgement" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 15 September 2008. p. 24.

- ↑ CIA 2002, p. 379.

- ↑ Meštrović (1996), p. 8.

- ↑ "ICTY "Prosecutor v. Krstic"" (PDF). United Nations. 5 March 2007. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ↑ "Six Senior Herceg-Bosna Officials Convicted" (Press release). The Hague: International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 29 May 2013. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- 1 2 The Prosecutor vs Milan Milutinović et al. – Judgement, 26 February 2009, pp. 88–89

- ↑ The Prosecutor vs Milan Milutinović et al. – Judgement, 26 February 2009, p. 416.

- ↑ Perritt, Henry H. Jr. (July 18, 2008). Kosovo Liberation Army: The Inside Story of an Insurgency. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0252033421.

- ↑ Morton, Jeffrey S.; Bianchini, Stefano; Nation, Craig; Forage, Paul, eds. (17 January 2004). Reflections on the Balkan Wars: Ten Years After the Break-up of Yugoslavia. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1403963321.

- ↑ Nation, R. Craig (8 July 2014). War in the Balkans, 1991–2002. contributions by Strategic Studies Institute. lulu.com. ISBN 978-1312339750.

- ↑ Morton, Jeffrey S. (2004). Reflections on the Balkan Wars. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 57. ISBN 1-4039-6332-0.

- ↑ "Renewed clashes near Kosovo border". BBC News. 28 January 2001. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ↑ "Kostunica warns of fresh fighting". BBC News. January 29, 2001.

- 1 2 Wood, Paul (20 March 2001). "Who are the rebels?". BBC News.

- ↑ "Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Macedonia, 2002 – Book XIII" (PDF). Skopje: State Statistical Office of the Republic of Macedonia. May 2005.

- ↑ "Macedonia's 'Liberation' Army: A Learner's Lexicon". World Press Review. Zurich. 48 (9). September 2001. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ↑ "UN arms embargo on Yugoslavia (FRY)". Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ↑ Blaz Zgaga; Matej Surc (2 December 2011). "Yugoslavia and the profits of doom". EUobserver. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ "Chile generals convicted over 1991 Croatia arms deal". BBC News. 20 January 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2012.

- ↑ "Paris terror attack: Why getting hold of a Kalashnikov is so easy". The Independent. 23 November 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ↑ "Resolution 47/121, 91st plenary meeting, The situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina". United Nations General Assembly. 18 December 1992. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ↑ "Human Rights Watch World Report 1993 - The former Yugoslav Republics". Helsinki Watch. 1 January 1993. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- 1 2 Marlise Simons (27 February 2007). "Court Declares Bosnia Killings Were Genocide". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ↑ Peter W. Galbraith. "Galbraith telegram" (PDF). United States Department of State.

- ↑ A resolution expressing the sense of the Senate regarding the massacre at Srebrenica in July 1995, thomas.loc.gov; accessed 25 April 2015.

- ↑ "Sense Tribunal: SERBIA FOUND GUILTY OF FAILURE TO PREVENT AND PUNISH GENOCIDE". Archived from the original on 30 July 2009. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- 1 2 Alexandra Sims (24 March 2016). "Radovan Karadzic guilty of genocide over Srebrenica massacre in Bosnia". The Independent. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ↑ Wood 2001, p. 57–75.

- ↑ "Prosecutor v. Vujadin Popovic, Ljubisa Beara, Drago Nikolic, Ljubomir Borovcanin, Radivoje Miletic, Milan Gvero, and Vinko Pandurevic" (PDF).

In the Motion, the Prosecution submits that both the existence and implementation of the plan to create an ethnically pure Bosnian Serb state by Bosnian Serb political and military leaders are facts of common knowledge and have been held to be historical and accurate in a wide range of sources.

- ↑ "ICTY: Radoslav Brđanin judgement". Archived from the original on 14 April 2009.

- ↑ "Tadic Case: The Verdict".

Importantly, the objectives remained the same: to create an ethnically pure Serb State by uniting Serbs in Bosnia and Herzegovina and extending that State from the FRY […] to the Croatian Krajina along the important logistics and supply line that went through opstina Prijedor, thereby necessitating the expulsion of the non-Serb population of the opstina.

- ↑ "Prosecuter v. Jadranko Prlic, Bruno Stojic, Slobodan Praljak, Milivoj Petkovic, Valentin Coric and Berislav Pusic" (PDF).

Significantly, the Trial Chamber held that a reasonable Trial Chamber, could make a finding beyond any reasonable doubt that all of these acts were committed to carry out a plan aimed at changing the ethnic balance of the areas that formed Herceg-Bosna and mainly to deport the Muslim population and other non-Croat population out of Herceg-Bosna to create an ethnically pure Croatian territory within Herceg-Bosna.

- ↑ "Judgement Summary for Jovica Stanišić and Franko Simatović" (PDF). ICTY. 30 May 2013. p. 2. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ↑ "Five Senior Serb Officials Convicted of Kosovo Crimes, One Acquitted". ICTY. 26 February 2009. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ↑ Campbell 2001, p. 58.

- ↑ Geldenhuys 2004, p. 34.

- 1 2 de Brouwer (2005), p. 10

- 1 2 de Brouwer (2005), pp. 9–10

- ↑ Robson, Angela (June 1993). "Rape: Weapon of War". New Internationalist (244). Archived from the original on 2010-08-17.

- ↑ Netherlands Institute for War Documentation Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Part 1 Chapter 9

- ↑ "Bosnia: Landmark Verdicts for Rape, Torture, and Sexual Enslavement - Criminal Tribunal Convicts Bosnian Serbs for Crimes Against Humanity". Human Rights Watch. Human Rights Watch. 22 February 2001.

- ↑ Simons, Marlise (June 1996). "For first time, Court Defines Rape as War Crime". The New York Times.

- ↑ de Brouwer (2005), p. 11

- ↑ Salzman 1998, p. 348–378.

- ↑ Vesna Peric Zimonjic (20 February 2006). "Film award forces Serbs to face spectre of Bosnia's rape babies". The Independent. Belgrade. Archived from the original on September 24, 2009. Retrieved 26 June 2009.

- ↑ "United Nations Commission on Breaches of Geneva Law in Former Yugoslavia", The International Fight Against Gender Inequality, 1997, archived from the original on 8 August 2009, retrieved 14 April 2014

- ↑ Card 1996, p. 5–18.

- ↑ Allen (1996), p. 77

- ↑ McGinn 2000, p. 174–180.

- 1 2 3 "Serb Gang-Rapes in Kosovo Exposed". Human Rights Watch. Human Rights Watch. March 20, 2000.

- 1 2 3 Kosovo: Rape as a Weapon of "Ethnic Cleansing", Human Rights Watch, retrieved 14 April 2015

- 1 2 Egan, p. 171.

- ↑ Toal & Dahlman 2011, p. 136–137.

- ↑ Brunborg, Lyngstad & Urdal 2003, p. 229–248.

- ↑ Smajić 2013, p. 124.

- ↑ Fink 2010, p. 469.

- ↑ Watkins 2003, p. 10.

- 1 2 UNHCR 2003.

- ↑ Human Rights Watch 2001.

- 1 2 OSCE 1999, p. 13.

- 1 2 Rowland, Jacky (22 March 2000). "Bleak outlook for Serb refugees". Belgrade: BBC News. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- 1 2 Council of Europe 1993, p. 9.

- ↑ UNHCR 2002, p. 1

- ↑ UNHCR 1993, p. 11.

- ↑ UNHCR 1993, p. 8.

- ↑ UNHCR 2000, p 319

- ↑ UNHCR 2002, p. 1

- ↑ UNHCR 2002, p. 1

- ↑ US Department of State (1994). "CROATIA HUMAN RIGHTS PRACTICES, 1993".

- ↑ UNHCR 1997.

- 1 2 3 Friedman 2013, p. 80.

- ↑ Krieger 2001, p. 90.

- 1 2 Human Rights Watch 1994, p. 7.

- 1 2 Human Rights Watch (2001). "Under Orders: War Crimes in Kosovo".

- ↑ Siblesz 1998, p. 10.

- ↑ World Bank 1996, p. 10.

- ↑ Meyers 2004, p. 136.

- ↑ Jha 2014, p. 68.

- ↑ Bicanic 2008, p. 158–173.

- ↑ OHCHR 1993, p. 23.

- ↑ OHCHR 1993, p. 19.

- 1 2 Erik Kirschbaum (July 13, 1995). "YUGOSLAV ECONOMY FORECAST TO GROW ONCE EMBARGO ENDS INFLATION WHIPPED, CENTRAL BANKER SAYS". JOC Group. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ↑ Jha 2014, p. 69.

- ↑ Jha 2014, p. 72.

- ↑ Magliveras 2002, p. 661–677.

- ↑ "UN tribunal investigating death of accused genocide mastermind Slobodan Milosevic". UN News. 12 March 2006. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ↑ Akhavan 2001, p. 7–31.

- ↑ "Karadžić verdict sends signal "no one is above the law": UN official". UN News. 24 March 2016. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ↑ "UN hails conviction of Mladic, the 'epitome of evil,' a momentous victory for justice". UN News. 22 November 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ↑ "APPEALS CHAMBER REVERSES ŠEŠELJ'S ACQUITTAL, IN PART, AND CONVICTS HIM OF CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY". United Nations Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals. 11 April 2018. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- ↑ "Serbia: Conviction of war criminal delivers long overdue justice to victims". Amnesty International. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- ↑ "UN genocide tribunal affirms life sentence of Serb paramilitary leader". UN News. 4 December 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ↑ "UN tribunal transfers former Bosnian Serb leader to UK prison". UN News. 8 September 2009. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ↑ "UN war crimes tribunal sentences Bosnian Serb general to life in jail". UN News. 30 November 2006. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ↑ "UN tribunal convicts former Serbian police official for crimes in Kosovo". UN News. 23 February 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ↑ "Mile Mrksic, a Serb Army Officer Convicted of War Crimes, Dies at 68". New York Times. 17 August 2015. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ↑ "UN war crimes tribunal sentences two former senior Yugoslav officers". UN News. 27 September 2007. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ↑ "UN tribunal upholds 35-year jail term for leader of breakaway Croatian Serb state". UN News. 8 October 2008. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ↑ "6 Bosnian Croats appeal UN war crimes convictions". News24. 20 March 2017.

- ↑ "Bosnian Croat commander convicted by UN tribunal to serve jail term in Italy". UN News. 25 April 2008. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ↑ "UN tribunal partially overturns convictions of two Bosnian Muslim commanders". UN News. 22 April 2008. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ↑ "Kosovo prison guard convicted by UN tribunal to serve rest of jail term in France". UN News. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ↑ Zaknic 1992, p. 115–124.

- ↑ "Milosevic: Important New Charges on Croatia". Human Rights Watch. The Hague: Human Rights Watch. 21 October 2001. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ↑ Off 2010, p. 218.

- ↑ Stanley Meisler and Carol J. Williams (31 May 1992). "Angry U.N. Votes Harsh Sanctions on Yugoslavia : Balkans: The Security Council, infuriated by bloody attacks in Bosnia-Herzegovina, imposes an oil embargo and other curbs. China, Zimbabwe abstain in 13-0 vote". LA Times. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ↑ Block, Robert; Bellamy, Christopher (10 November 1993). "Croats destroy Mostar's historic bridge". The Independent.

- ↑ Carol J. Williams (5 August 1994). "Serbia Cuts Off Bosnian Rebels : Balkans: Belgrade, under international pressure, says it is denying supplies of fuel and arms to forces it has supported. Washington cautiously welcomes move". LA Times. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ↑ "Returns to Bosnia and Herzegovina reach 1 million: This is a summary of what was said by UNHCR spokesperson Ron Redmond – to whom quoted text may be attributed – at today's press briefing at the Palais des Nations in Geneva". UNHCR, The UN Refugee Agency. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 21 September 2004. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ↑ "20,000 Attend a Protest Against Serbian Leader". The New York Times. 10 March 1996. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ↑ "NATO attack on Yugoslavia begins". CNN. 24 March 1999. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

Sources

Books

- Allen, Beverly (1996). Rape Warfare: The Hidden Genocide in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Croatia. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-2818-6.

- Baker, Catherine (2015). The Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s. Macmillan International Higher Education. ISBN 978-1-137-39899-4.

- Bideleux, Robert; Jeffries, Ian (2007). A history of Eastern Europe: crisis and change (2nd ed.). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-415-36627-5. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- Brown, Cynthia; Karim, Farhad (1995). Playing the "Communal Card": Communal Violence and Human Rights. New York: Human Rights Watch. ISBN 978-1-56432-152-7.

- Brouwer, Anne-Marie de (2005). Supranational Criminal Prosecution of Sexual Violence. Intersentia. ISBN 90-5095-533-9.

- Campbell, Kenneth (2001). Genocide and the Global Village. Springer. ISBN 0312299281.

- Cohen, Leonard J.; Dragović-Soso, Jasna, eds. (2008). State Collapse in South-Eastern Europe: New Perspectives on Yugoslavia's Disintegration. Purdue University Press. p. 323. ISBN 9781557534606.

- Egan, James. 1000 Facts About Countries. 2. Lulu.com. p. 171. ISBN 9781326776725.

- Fink, George (2010). Stress of War, Conflict and Disaster. Academic Press. ISBN 9780123813824.

- Finlan, Alastair (2004). The Collapse of Yugoslavia 1991–1999. Essential Histories. Oxford, UK: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84176-805-2.

- Friedman, Francine (2013). Bosnia and Herzegovina: A Polity on the Brink. Routledge. ISBN 9781134527540.

- Gagnon, Valère Philip (2004). The Myth of Ethnic War: Serbia and Croatia in the 1990s. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-7291-6.

- Geldenhuys, Dean (2004). Deviant Conduct in World Politics. Springer. ISBN 0230000711.

- Glenny, Misha (1996). The fall of Yugoslavia: the third Balkan war. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-026101-X.

- Goldstein, Ivo (1999). Croatia: A History. C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 1-85065-525-1.

- Ingrao, Charles; Emmert, Thomas A., eds. (2003). Confronting the Yugoslav Controversies: A Scholars' Initiative (2nd ed.). Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-617-4.

- Jha, U. C. (2014). Armed Conflict and Environmental Damage. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. ISBN 9382652817.

- Krieger, Heike (2001). Heike Krieger, ed. The Kosovo Conflict and International Law: An Analytical Documentation 1974-1999. Cambridge University Press. p. 90. ISBN 9780521800716.

- Meštrović, Stjepan Gabriel (1996). Genocide After Emotion: The Postemotional Balkan War. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-12294-5.

- Meyers, Eytan (2004). International Immigration Policy: A Theoretical and Comparative Analysis. Springer. ISBN 1403978379.

- Naimark, Norman; Case, Holly M. (2003). Yugoslavia and Its Historians: Understanding the Balkan Wars of the 1990s. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4594-3. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- Off, Carol (2010). The Lion, the Fox and the Eagle. Random House of Canada. p. 218. ISBN 0307370771.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2010). Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-48750-4.

- Rogel, Carole (2004). The Breakup of Yugoslavia and Its Aftermath. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-32357-7. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- Shaw, Martin (2013). Genocide and International Relations: Changing Patterns in the Transitions of the Late Modern World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1107469104.

- Smajić, Aid (2013). "Bosnia and Herzegovina". In Nielsen, Jørgen; Akgönül, Samim; Alibašić, Ahmet; Racius, Egdunas. Yearbook of Muslims in Europe. 5. BRILL. ISBN 9789004255869.

- Tanner, Marcus (2001). Croatia : a nation forged in war (2nd ed.). New Haven; London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09125-7.

- Toal, Gerard; Dahlman, Carl T. (2011). Bosnia Remade: Ethnic Cleansing and its Reversal. Oxford University Press. pp. 136, 137. ISBN 9780190207908.

- Watkins, Clem S. (2003). The Balkans. Nova Publishers. p. 10. ISBN 9781590335253.

- Aleksandar, Bosković; Dević, Ana; Gavrilović, Darko; Hašimbegović, Elma; Ljubojević, Ana; Perica, Vjekoslav; Velikonja, Mitja, eds. (2011). Political Myths in the Former Yugoslavia and Successor States: A Shared Narrative. Institute for Historical Justice and Reconciliation. ISBN 90-8979-067-5.

- Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Russian and European Analysis (2002). Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990–1995. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency. ISBN 978-0-16-066472-4.

- Council of Europe (1993). Documents (working Papers) 1993. p. 9. ISBN 9789287123329.

- Ullman, Richard Henry (1996). The World and Yugoslavia's Wars. Council on Foreign Relations. ISBN 978-0-87609-191-3.

- World Bank (1996). Bosnia and Herzegovina: Toward Economic Recovery. World Bank Publications. p. 10. ISBN 0821336738.

Scientific journal articles

- Akhavan, Payam (2001). "Beyond Impunity: Can International Criminal Justice Prevent Future Atrocities?". American Journal of International Law. 95 (1): 7–31. doi:10.2307/2642034.

- Bicanic, Ivo (2008). "Croatia". Southeast European and Black Sea Studies. 1 (1): 158–173. doi:10.1080/14683850108454628.

- Brunborg, Helge; Lyngstad, Torkild Hovde; Urdal, Henrik (2003). "Accounting for Genocide: How Many Were Killed in Srebrenica?". European Journal of Population / Revue européenne de Démographie. 19 (3): 229–248. doi:10.1023/A:1024949307841. JSTOR 20164231.

- Card, Claudia (1996). "Rape as a Weapon of War". Hypatia. 11 (4): 5–18. doi:10.1111/j.1527-2001.1996.tb01031.x. ISSN 0887-5367. JSTOR 3810388.

- Guzina, Dejan (2003). "Socialist Serbia's Narratives: From Yugoslavia to a Greater Serbia". International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society. 17 (1): 91–111. doi:10.1023/A:102534101.

- Magliveras, Konstantinos D. (2002). "The Interplay Between the Transfer of Slobodan Milosevic to the ICTY and Yugoslav Constitutional Law". European Journal of International Law. 13 (3): 661–677. doi:10.1093/ejil/13.3.661.

- McGinn, Therese (2000). "Reproductive Health of War-Affected Populations: What Do We Know?". International Family Planning Perspectives. 26 (4): 174–180. doi:10.2307/2648255. ISSN 0190-3187. JSTOR 2648255.

- Salzman, Todd A. (1998). "Rape Camps as a Means of Ethnic Cleansing: Religious, Cultural, and Ethical Responses to Rape Victims in the Former Yugoslavia". Human Rights Quarterly. 20 (2): 348–378. doi:10.1353/hrq.1998.0019.

- Wood, William B. (2001). "Geographic Aspects of Genocide: A Comparison of Bosnia and Rwanda". Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 26 (1): 57–75. doi:10.1111/1475-5661.00006. JSTOR 623145.

- Zaknic, Ivan (1992). "The Pain of Ruins: Croatian Architecture under Siege". Journal of Architectural Education. 46 (2): 115–124. doi:10.1080/10464883.1992.10734547.

Other sources

- Bassiouni, M. Cherif (28 December 1994). "Final report of the United Nations Commission of Experts established pursuant to security council resolution 780 (1992), Annex III – The military structure, strategy and tactics of the warring factions". United Nations. Archived from the original on July 28, 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- Bassiouni, M. Cherif (28 December 1994). "Final report of the United Nations Commission of Experts established pursuant to security council resolution 780 (1992), Annex IV – The policy of ethnic cleansing". United Nations. Archived from the original on May 4, 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- Ferguson, Kate. An investigation into the irregular military dynamics in Yugoslavia, 1992-1995. Diss. University of East Anglia, 2015.

- Siblesz, H.H. (1998). "History of Sandzak" (pdf). Refworld. p. 10.

- "The Prosecutor vs Milan Milutinovic et al – Judgement" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 26 February 2009.

- Human Rights Watch (1994). "Human Rights Abuses of Non-Serbs In Kosovo, Sandñak and Vojvodina" (PDF).

- Human Rights Watch (2001). "Kosovo: Under Orders".

- Human Rights Watch (2001). "Milosevic: Important New Charges on Croatia".

- OHCHR (1993). "Fifth periodic report on the situation of human rights in the territory of the former Yugoslavia submitted by Mr. Tadeusz Mazowiecki". Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- OSCE (1999). "KOSOVO / KOSOVA: As Seen, As Told". p. 13.

- UNHCR (1993). "The State of the World's Refugees 1993" (PDF).

- UNHCR (1997). "U.S. Committee for Refugees World Refugee Survey 1997 – Yugoslavia".

- "2002 UNHCR Statistical Yearbook: Croatia" (pdf). UNHCR. 2002.

- "2002 UNHCR Statistical Yearbook: Macedonia". UNHCR. 2000.

- "2002 UNHCR Statistical Yearbook: Slovenia" (pdf). UNHCR. 2002.

- "2002 UNHCR Statistical Yearbook: Serbia" (pdf). UNHCR. 2002.

- UNHCR (2003). "Bosnian refugees in Australia: identity, community and labour market integration" (PDF).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yugoslav wars. |

- Video on the Conflict in the Former Yugoslavia from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

- Information and links on the Third Balkan War (1991–2001)

- Nation, R. Craig. "War in the Balkans 1991–2002"

- Radović, Bora, Jugoslovenski ratovi 1991–1999 i neke od njihovih društvenih posledica (PDF) (in Serbian), RS: IAN, archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04, retrieved 2016-02-08

- Wiebes, Cees. Intelligence and the War in Bosnia 1992–1995, Publisher: Lit Verlag, 2003

- Yugoslav wars at Curlie (based on DMOZ)

- List of Yugoslav wars movies

- Archive about the wars

| Pre–1918 | 1918–1929 | 1929–1945 | 1941–1945 | 1945–1946 | 1946–1963 | 1963–1992 | 1992–2003 | 2003–2006 | 2006–2008 | 2008– | |

| Slovenia | See also Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia 1868–1918 Kingdom of Dalmatia 1815–1918 Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina 1878–1918 |

See also Banat, Bačka and Baranja 1918–1919 Italian province of Zadar 1920–1947 |

Annexed bya Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany |

Democratic Federal Yugoslavia 1945–1946 Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia 1946–1963 Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia 1963–1992 Consisted of the Socialist Republics of Serbia (1945–1992) (included the autonomous provinces of Vojvodina and Kosovo) |

Ten-Day War | ||||||

| Dalmatia | Puppet state of Nazi Germany. Parts annexed by Fascist Italy. Međimurje and Baranja annexed by Hungary. |

Croatian War of Independence | |||||||||

| Slavonia | |||||||||||

| Croatia | |||||||||||

| Bosnia | Bosnian War Consists of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (1995–present), Republika Srpska (1995–present) and Brčko District (2000–present). | ||||||||||

| Herzegovina | |||||||||||

| Vojvodina | Part of the Délvidék region of Hungary | Autonomous Banatd (part of the German Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia) |

Federal Republic of Yugoslavia | State Union of Serbia and Montenegro | Includes the autonomous province of Vojvodina | ||||||

| Serbia | Kingdom of Serbia 1882–1918 |

Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia 1941–1944 e | |||||||||

| Kosovo | Part of the Kingdom of Serbia 1912–1918 |

Mostly annexed by Albania 1941–1944 along with western Macedonia and south-eastern Montenegro |

|||||||||

| Metohija | Kingdom of Montenegro 1910–1918 Metohija controlled by Austria-Hungary 1915–1918 | ||||||||||

| Montenegro | Protectorate of Montenegrof 1941–1944 |

||||||||||

| Macedonia | Part of the Kingdom of Serbia 1912–1918 |

Annexed by the Kingdom of Bulgaria 1941–1944 |

|||||||||

|

| ||||||||||